Building a Governance Reference Model for a Specific Enterprise: Addressing Social Challenges Through Structured Solution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Trajectory of Methodological Pluralism Developments

- The social context within which problematic situations exist is multidimensional [32]. Different paradigms focus on different aspects, each highlighting some and omitting others, indicating the benefit of using a variety of methodologies.

- Interventions are generally phased with stages on discovery, approach design, execution and review. Each stage will incorporate different tasks and perspectives, each benefitting from a different methodology or method [32].

- The lack of success of traditional methods and methodologies to resolve issues in practice has led to the consideration of new ways of thinking and entertaining the thought of multiple methodologies [104].

- Multiple methodologies enable a form of ‘triangulation’ that provides more confidence in findings if the same results are obtained from different methodologies [105].

2.2. Contemporary Theories of Social Systems

2.3. Conceptual Critique of Governance Models

2.4. Systemic Dimensions

- The vertical dimension represents the association between the goals of the organisation as defined by its controlling board or owner and its operations. It incorporates its culture and ways of working. Some of these are explicit, while others are implicit.

- The dimension of progression represents the means–end processes of achievement. It is the series of observable actions that an organisation might undertake to achieve, or not, its goals. It may be taking place as observable behaviour but can equally be unobservable and represent strategic plans and intent. It is this dimension that really focuses on boundary critique and Midgley’s [48] process philosophy.

- The transverse dimension represents the breadth of multiple concurrent actions and the necessary coordination between them. Within the organisation, it could be the individuals in a team, the various departments that need to work together to achieve successful service delivery, or the coordination of service deliveries and business units for optimal resource utilisation, or work packages within a research programme.

- The biosphere is the integration of the three perspectives placed within its environment and considered as a single reality. It is considered that there is no distinction between them, and they can only be separated by abstraction. This is the boundary critique proposed by Midgley. This abstraction incorporates both autonomous determination and environmental government “like two currents of opposing direction, inseparably united” [25] (p. 101).

The Maladaptive Perspective

2.5. Mapping Methods to System’s Three Perspectives

3. Results

3.1. Candidate Methods

3.2. Philosophical Commitments

- Ontological commitment: Social reality is understood as dynamic and emergent, constituted by processes of interaction, interpretation, and systemic adaptation.

- Epistemological commitment: Knowledge arises through hermeneutic engagement, where understanding develops in a circular movement between the part and the whole, between pre-understanding and new interpretation.

- Axiological commitment: Inquiry is not value-neutral. Pragmatism, as emphasised in the extract, requires acknowledgement that values shape both the questions asked and the solutions sought. Governance research, therefore, must bring its value-laden character into the open.

4. Discussion

4.1. Methods for Understanding

4.2. The Main Systems Methods

4.2.1. Soft Systems Methodology

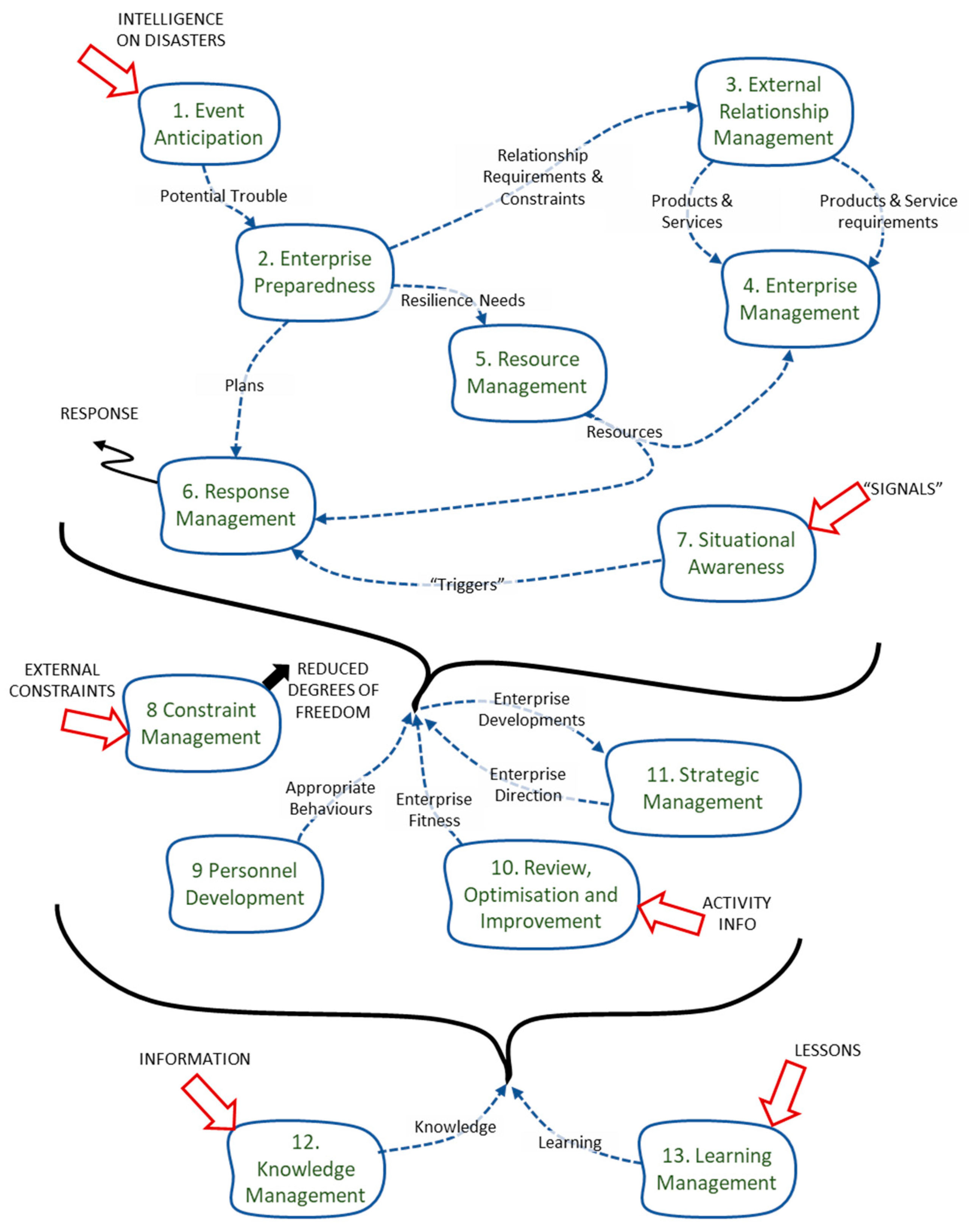

4.2.2. Viable System Model

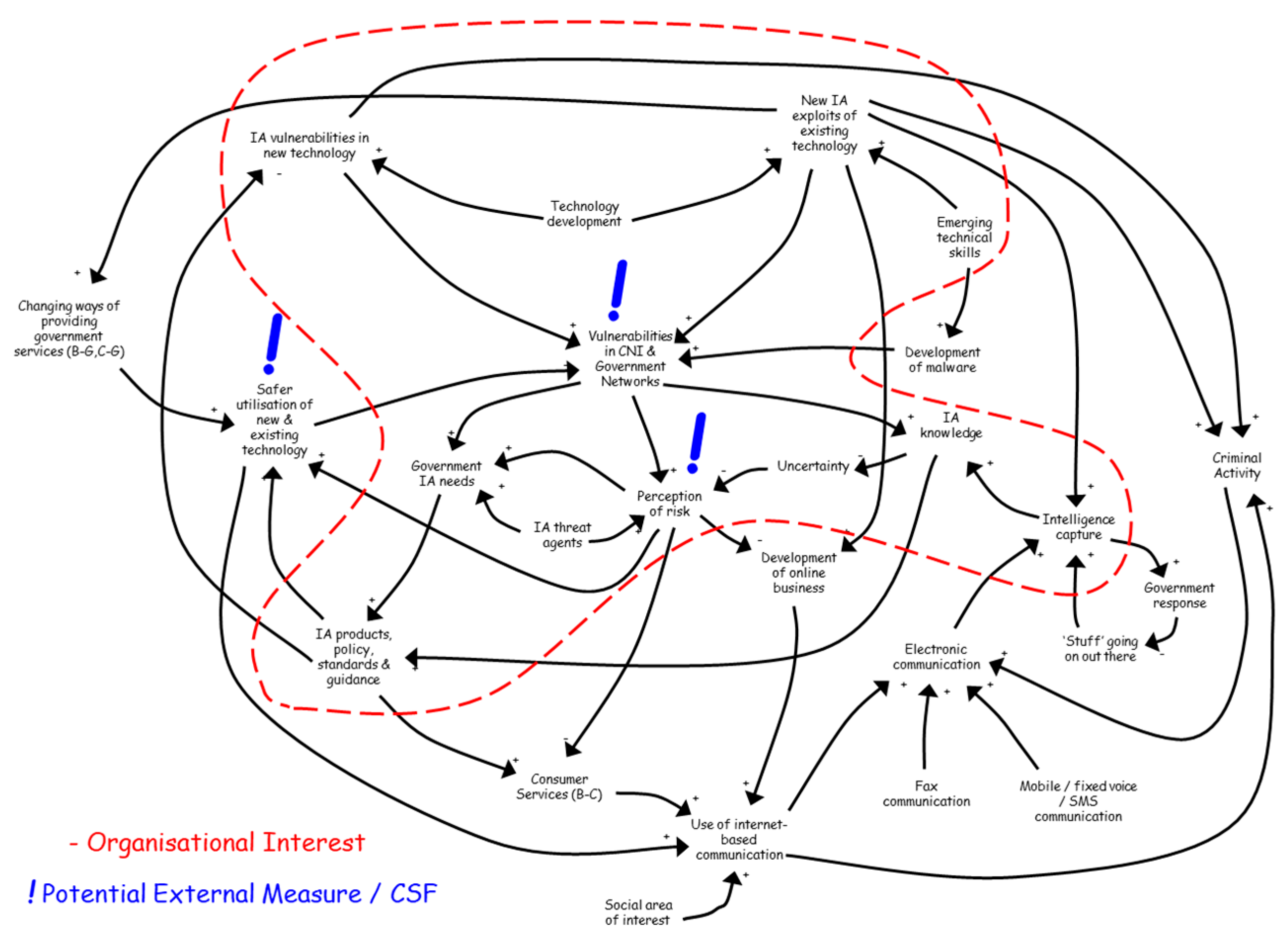

4.2.3. System Dynamics, Including Causal Loop Modelling

4.2.4. Dependency Modelling

4.3. Shaping with Respect to the Causal Texture of Organisational Environments

4.4. Augmenting Thinking with Generic SSM Models

4.5. Utility of Methods

5. Assumptions and Limitations of the Reference Model

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| CLD | Causal Loop Diagram |

| CPTM | Consensus Primary Task Model |

| MPA | Multi-Perspective Approach |

| SD | System Dynamics |

| SSM | Soft Systems Methodology |

| VSM | Viable System Modelling |

References

- George, G.; Howard-Grenville, J.; Joshi, A.; Tihanyi, L. Understanding and tackling societal grand challenges through management research. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1880–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J. Self-Producing Systems: Implications and Applications of Autopoiesis; Plenum Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.C. Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- James, W. Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking; Longmans: New York, NY, USA, 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Vivo, P.; Katz, D.M.; Ruhl, J.B. A Complexity science approach to law and governance. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 2024, 382, 20230166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, C.B.; Katina, P.F.; Bradley, J.M. Complex system governance: Concept, challenges, and emerging research. Int. J. Syst. Syst. Eng. 2014, 5, 263–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, R.J.; Costa, S.N.; Romero, D. A Governance Reference Model for Virtual Enterprises. In Proceedings of the 15th Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises (PROVE), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 6–8 October 2014; pp. 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, C.B.; Katina, P.F.; Chesterman, C.W.; Pyne, J.C. (Eds.) Complex System Governance: Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, J. The value of systems thinking for and in regulatory governance: An evidence synthesis. SAGE Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R. Cybernetics of Governance: The Cybersyn Project 1971–1973. In Governing Complexity; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.; Millar, G. The Viable Governance Model—A Theoretical Model for the Governance of IT. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baijens, J.; Huygh, T.; Helms, R. Establishing and theorising data analytics governance: A descriptive framework and a VSM-based view. J. Bus. Anal. 2022, 5, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R. Cybersyn, Big data, variety engineering and governance. AI Soc. 2022, 37, 1163–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, A. Governance for sustainability: Learning from VSM practice. Kybernetes 2015, 44, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaninger, M. Governance for intelligent organizations: A cybernetic contribution. Kybernetes 2019, 48, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J. Models of governance—A viable systems perspective. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2002, 9, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huygh, T.; De Haes, S. Investigating IT governance through the Viable System Model. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2019, 36, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, R.C.; Ashby, W.R. Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 1970, 1, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulibarri, N.; Emerson, K.; Imperial, M.T.; Jager, N.W.; Newig, J.; Weber, E. How does collaborative governance evolve? Insights from a medium-N case comparison. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 617–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, P. Complexity and Postmodernism: Understanding Complex Systems; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerhoff, G. Analytical Biology; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, W.R. An Introduction to Cybernetics; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, F.; Trist, E. The causal texture of organizational environments. Hum. Relat. 1965, 18, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trist, E. The Environment and system-response capability. Futures 1980, 12, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angyal, A. Foundations for a Science of Personality; 4th printing; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, F.E. Adaptation to Turbulent Environments. In Towards a Social Ecology; Emery, F.E., Trist, E.L., Eds.; Plenum Publishing Company Ltd.: London, UK, 1973; Chapter 5; pp. 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Trist, E. Andras Angyal and Systems Thinking. In Planning for Human Systems; Choukroun, J.-M., Snow, R., Eds.; Busch Centre, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; Chapter 9; pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.C. Critical Systems Practice 2: Produce—Constructing a Multimethodological Intervention Strategy. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 38, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, G.; Nicholson, J.D.; Brennan, R. Dealing with challenges to methodological pluralism: The paradigm problem, psychological resistance and cultural barriers. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 62, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J. Variety is the spice of life: Combining soft and hard OR/MS methods. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2000, 7, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, I.; Mingers, J. The use of multimethodology in practice—Results of a survey of practitioners. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2002, 53, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J.; Brocklesby, J. Multimethodology: Towards a framework for mixing methodologies. Omega 1997, 25, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, J. A Methodology for Modelling Organisational Governance: Building the ‘Good Regulator’ Model for Organisations Through the Application of Multiple Systems Methods. Cranfield University. 2024. Available online: https://dspace.lib.cranfield.ac.uk/handle/1826/23723 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Babüroǵlu, O.N. Tracking the development of the Emery–Trist systems paradigm (ETSP). Syst. Pract. 1992, 5, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.A. The Psychology of Personal Constructs: Volume One A Theory of Personality; W.W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Churchman, C.W. The Systems Approach and Its Enemies; Basic Books, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, W.; Reynolds, M. Critical Systems Heuristics. In Systems Approaches to Managing Change: A Practical Guide; Reynolds, M., Holwell, S.S., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2010; pp. 243–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice: Includes a 30-Year Retrospective; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, G. Imaginization: The Art of Creative Management; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eden, C. Analyzing cognitive maps to help structure issues or problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 159, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. Social Systems; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mingers, J. Can social systems be autopoietic? Assessing Luhmann’s social theory. Sociol. Rev. 2002, 50, 278–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaques, E. The Development of intellectual capability: A discussion of stratified systems theory. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1986, 22, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinston, W. Purpose & translation of values into action. Syst. Res. 1986, 3, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques, E. Requisite Organization: A Total System for Effective Managerial Organization and Managerial Leadership for the 21st Century, 2nd revised ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stamp, G. Levels and types of managerial capability. J. Manag. Stud. 1981, 18, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamp, G. The Individual, the Organisation and the Path to Mutual Appreciation. Bioss.com. Available online: https://www.bioss.com/gillian-stamp/the-individual-the-organisation-and-the-path-to-mutual-appreciation/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Midgley, G. Systemic Intervention: Philosophy, Methodology, and Practice. In Contemporary Systems Thinking; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.C. Critical systems practice 1: Explore—Starting a multimethodological intervention. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2020, 37, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angyal, A. A Logic of Systems. In Systems Thinking, Vol. One; Emery, F.E., Ed.; Penguin Books Ltd.: Harmondsworth, UK, 1981; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D.C. The methodological basis of systems theory. Acad. Manag. J. 1972, 15, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, R.C. The Information transfer required in regulatory processes. IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern. 1969, 5, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bertalanffy, L. General systems theory. Gen. Syst. 1956, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, K.E. General systems theory—The skeleton of science. Manag. Sci. 1956, 2, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, W.R. Design for a Brain; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblueth, A.; Wiener, N.; Bigelow, J. Behavior, purpose and teleology. Philos. Sci. 1943, 10, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, N. Cybernetics, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. The Architecture of complexity. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 1962, 106, 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, R.G. System Dynamics Modelling: A Practical Approach; Springer Science+Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.W. Industrial Dynamics; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, J.W. The Beginning of System Dynamics. In Proceedings of the International Meeting of the System Dynamics Society, Stuttgart, Germany, 10–14 July 1989; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, G.A. The Systems Approach. In Systems Behaviour; Beishon, J., Peters, G., Eds.; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1969; Chapter 4; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. Brain of the Firm, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. The Heart of Enterprise; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P. Information systems and systems thinking: Time to unite? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 1988, 8, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.C. Nature of ‘Soft’ systems thinking: The work of Churchman, Ackoff and Checkland. J. Appl. Syst. Anal. 1982, 9, 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Churchman, C.W. The Systems Approach; Delta/Dell Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Churchman, C.W. Perspectives of the systems approach. Interfaces 1974, 4, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchman, C.W.; Emery, F. On Various Approaches to the Study of Organizations. In Proceedings of the First International Conference of Operational Research and the Social Sciences, Cambridge, UK, 14–18 September 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P.; Scholes, J. Soft Systems Methodology in Action; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, D.; Whitney, D.; Stavros, J.M. Appreciative Inquiry Handbook for Leaders of Change, 2nd ed.; Crown Custom Publishing, Inc.: Brunswick, OH, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Varey, R.J. Appreciative Systems: A Summary of the Work of Sir Geoffrey Vickers. Working Paper. Salford, UK, 1998. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252067023_Appreciative_Systems_A_summary_of_the_work_of_Sir_Geoffrey_Vickers (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Vickers, G. Freedom in a Rocking Boat: Changing Values in an Unstable Society; Penguin Books Ltd.: Harmondsworth, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs, W. Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together: A Pioneering Approach to Communicating in Business and in Life; Currency: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ackoff, R.L. Resurrecting the future of operational research. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1979, 30, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M.; Sterman, J.D. Systems thinking and organizational learning: Acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1992, 59, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, W. Beyond methodology choice: Critical systems thinking as critically systemic discourse. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2003, 54, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocklesby, J. Let the jury decide: Assessing the cultural feasibility of total systems intervention. Syst. Pract. 1994, 7, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, R.L.; Jackson, M.C. Creative Problem Solving: Total Systems Intervention; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Frandberg, T. Systems Thinking—A Study of Alternatives of R. Flood, M. Jackson, W. Ulrich, G. Midgley. Int. J. Comput. Syst. Signals 2003, 4, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, W.J. Critical Systems Thinking and Pluralism: A New Constellation. Ph.D. Thesis, City University London, London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, W.J. Discordant pluralism: A new strategy for critical systems thinking. Syst. Pract. 1996, 9, 605–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.C. Systems Approaches to Management; Kluwer Academic/Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.C. The Power of multi-methodology: Some thoughts for John Mingers. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2003, 54, 1300–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.C.; Keys, P. Towards a system of systems methodologies. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1984, 35, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midgley, G. The Sacred and profane in critical systems thinking. Syst. Pract. 1992, 5, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, G. Pluralism and the legitimation of system science. Syst. Pract. 1992, 5, 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Midgley, G. Science as systemic intervention: Some implications of systems thinking and complexity for the philosophy of science. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2003, 16, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J. Paradigm wars: Ceasefire announced—Who will set up the new administration? J. Inf. Technol. 2004, 19, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J. Classifying Philosophical assumptions: A reply to ormerod. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2005, 56, 465–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J.; Gill, A. (Eds.) Multimethodology: The Theory and Practice of Combining Management Science Methodologies; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Oliga, J.C. Methodological foundations of systems methodologies. Syst. Pract. 1988, 1, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J. Realizing information systems: Critical realism as an underpinning philosophy for information systems. Inf. Organ. 2004, 14, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, M.; Lock, K.; Popay, J.; Savona, N.; Cummins, S.; McGill, E.; Penney, T.; Anderson de Cuevas, R.; Er, V.; Orton, L.; et al. Guidance on Systems Approaches to Local Public Health Evaluation Part 1: Introducing Systems Thinking; NIHR School for Public Health Research: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, M.; Lock, K.; Popay, J.; Savona, N.; Cummins, S.; McGill, E.; Penney, T.; Anderson de Cuevas, R.; Er, V.; Orton, L.; et al. Guidance on Systems Approaches to Local Public Health Evaluation Part 2: What to Consider When Planning a Systems Evaluation; NIHR School for Public Health Research: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wight, D.; Wimbush, E.; Jepson, R.; Doi, L. Six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID). J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, P.; O’Mahoney, J.; Vincent, S. Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism: A Practical Guide; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Longhofer, J.; Floersch, J. The coming crisis in social work: Some thoughts on social work and science. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2012, 22, 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, R. Evidence-based Policy: The Promise of ‘Realist Synthesis’. Evaluation 2002, 8, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S. Realist evaluation: An immanent critique. Nurs. Philos. 2015, 16, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon-Baker, P. Making paradigms meaningful in mixed methods research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2016, 10, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.C. Present positions and future prospects in management science. Omega 1987, 15, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormerod, R.J. The design of organisational intervention: Choosing the approach. Omega 1997, 25, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.C. Pluralism in Systems Thinking and Practice. In Multimethodology: The Theory and Practice of Combining Management Science Methodologies; Mingers, J., Gill, A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1997; pp. 347–378. [Google Scholar]

- Mingers, J. Systems Thinking, Critical Realism and Philosophy: A Confluence of Ideas; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T. The Social System; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The Theory of Communicative Action, Volume 2: The Critique of Functional Reason; McCarthy, T., Translator; Heinemann: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, C. Multiple Systems Thinking Methods for Resilience Research. MSc Dissertation, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, G. A Systems Approach to Student’s Motivation and Academic Achievement. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aston in Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Baburoglu, O.N. The Vortical Environment: The Fifth in the Emery-Trist Levels of Organizational Environments. Hum. Relat. 1988, 41, 181–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, F.E. Active Adaptation. In Futures We Are In; Martinus Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1977; pp. 67–131. [Google Scholar]

- Angyal, A. Neurosis and Treatment: A Holistic Theory; The Viking Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, B. Systems: Concepts, Methodologies, and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, D.F.; Vennix, J.A.M.; Richardson, G.P.; Rouwette, E.A.J.A. Group model building: Problem structuring, policy simulation and decision support. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2007, 58, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. Diagnosing the System for Organizations; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, D. A Dependency Modelling Manual; Hereford, UK, 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305883044_A_Dependency_Modelling_Manual (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- The Open Group. Dependency Modeling (O-DM): Constructing a Data Model to Manage Risk and Build Trust between Inter-Dependent Enterprises. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305884742_Open_Group_Standard_Dependency_Modeling_O-DM (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Wilson, B.; Van Haperen, K. Soft Systems Thinking, Methodology and the Management of Change; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eden, C. Cognitive mapping. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1988, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, R.L.; Carson, E.R. Dealing with Complexity: An Introduction to the Theory and Applications of Systems Science, 2nd ed.; London Plenum Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, J. A Summary Report on the Systems Approach to the Development of the Grounds Well Consortium. 2020, pp. 1–18. Available online: https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/groundswell/wp-content/uploads/sites/3722/2020/12/20201202-GroundsWell-Systems-Approach.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Brown, J.; Isaacs, D.; Community, T.W.C. The World Café: Shaping Our Futures through Conversations That Matter; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, G.; Wright, G. Scenario Thinking: Preparing Your Organization for the Future in an Unpredictable World, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, J. Using Systems Techniques to Define Information Requirements; The Open Group: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, J.; Riley, T.; Wright, C. Using Multiple Perspectives to Design Resilient Systems for Agile Enterprises. In Proceedings of the 7th Annual IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon 2013), Orlando, FL, USA, 15–18 April 2013; pp. 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, J.; Wright, C.; Kiparoglou, V. Building Resilience into Systems. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon 2012), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 19–22 March 2012; pp. 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Kiparoglou, V.; Williams, M.; Hilton, J. A Framework for Resilience Thinking. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2012, 8, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. Introduction to Systems Theory; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Gutiérrez, A.G.; Cardoso Castro, P.P.; Tejeida-Padilla, R. A Methodological Proposal for the Complementarity of the SSM and the VSM for the Analysis of Viability in Organizations. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2021, 34, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfagharian, M.; Romme, A.G.L.; Walrave, B. Why, When, and How to Combine System Dynamics with Other Methods: Towards an Evidence-Based Framework. J. Simul. 2018, 12, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P. Soft systems methodology: A thirty year retrospective. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2000, 17, S11–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P.; Poulter, J. Learning for Action: A Short Definitive Account of Soft Systems Methodology and Its Use for Practitioners, Teachers and Students; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, B. Soft Systems Methodology: Conceptual Model Building and Its Contribution; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo, R.; Reyes, A. Organizational Systems: Managing Complexity with the Viable Systems Model; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Rios, J. Design and Diagnosis for Sustainable Organizations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Galea, S.; Riddle, M.; Kaplan, G.A. Causal Thinking and Complex System Approaches in Epidemiology. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 39, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroeck, P.; Goossens, J.; Clemens, M. Tackling Obesities: Future Choices—Building the Obesity System Map, Foresight. 2007; p. 80. Available online: www.foresight.gov.uk (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Meadows, D. Leverage Points Places to Intervene in a System, Hartland VT, USA. 1999. Available online: http://www.donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/Leverage_Points.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Stroh, D.P. Systems Thinking for Social Change; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Besselink, D.; van der Lucht, F.; Barsties, L.; van der Vliet, M.J.; Kuijpers, T.G.; Lemmens, L.; Finnema, E.J.; Berg, S.W.v.D. Uncovering the Dynamic System Driving Older Adults’ Vitality: A Causal Loop Diagram Co-Created with Dutch Older Adults. Health Expect. 2025, 28, e70344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vennix, J.A.M. Group Model Building: Facilitating Team Learning Using System Dynamics; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman, J.D. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Maani, K.E.; Cavana, R.Y. Systems Thinking and Modelling: Understanding Change and Complexity; Pearson Education: Auckland, New Zealand, 2000. [Google Scholar]

| No | Requirement Statement |

|---|---|

| R1 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must enable boundary analysis. |

| R2 | It must be possible to see the effects of history, corporate memory, and drives to act. |

| R3 | Changes within the system (organisation) can be identified regarding necessary activities as the organisation adapts to environmental changes. |

| R4 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent ‘frames’, the perspective taken by the relevant management team according to differing levels of abstraction. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation is likely to be recursive (nested) with increasing granularity both horizontally and vertically. |

| R5 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to determine holistically activities relevant to the agreed frames, but maintain logical dependencies and capture the richness of interaction. |

| R6 | Sub-organisations within the organisation or enterprise can be identified that have their own discrete properties (purpose). |

| R7 | It should be possible to determine clusters of elements that collaborate at short range and to indicate the longer-range inter-relationships. |

| R8 | Dependencies between elements must be captured. |

| R9 | Measures of performance can be identified. |

| R10 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent the non-linearity of relationships. |

| R11 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation can capture the feedback within the system, between the system and the environment and within the environment. |

| R12 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must enable one to capture/integrate the environmental inter-relationships as well as internal peer–peer inter-relationships. |

| R13 | The organisation can be modelled in its wider context. |

| Orientation | Match to Requirements | Suitable Systems Method | Use of Method | Secondary Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Biosphere | R1. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must enable boundary analysis. | Extended MPA | Capture perspectives | Use of Appreciative Inquiry in a World Café construct. |

| 6 Questions/SSM (Checkland) | Develop consensus on purpose and key high-level activities (‘what’ should be performed to achieve purpose) | |||

| R3. Changes within the system (organisation) can be identified with regard to necessary activities as the organisation adapts to environmental changes. | SSM (Wilson) | Re-model CPTM with revised Root Definitions. Enables identification of activities no longer relevant and additional activities to be included | May result from periodic re-visit of purpose (6 Questions, SSM (Checkland) PQR. | |

| Dependency Modelling | Map the internal and external dependencies contributing to the organisation working well | Specific events captured by CLD Scenario thinking/planning exercise | ||

| R10. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent the non-linearity of relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | Logical dependencies between activities | ||

| VSM | Exploration of the environmental interactions and internal connections | Consideration of Angyal’s autonomy and heteronomy. | ||

| R11. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation can capture the feedbacks within the system, between the system and environment and within the environment. | System Dynamics | Causal Loop Diagrams | Informed by E&T Causal Textures | |

| R12. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must enable one to capture/integrate the environmental inter-relationships as well as internal peer–peer inter-relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | Modelling ‘System Served’ and detailed analysis of logical dependencies. | ||

| VSM | Exploration of the environmental interactions and internal connections | Consideration of Angyal’s autonomy and heteronomy. | ||

| Informed by E&T Causal Textures | ||||

| R13. The organisation can be modelled in its wider context. | SSM (Wilson) | Modelling ‘System Served’ | ||

Vertical Dimension | R2. It must be possible to see the effects of history, corporate memory and drives to act. | Cognitive Maps | With respect to personal constructs (Kelly), seek to capture the organisational constructs | Kinston’s hierarchy of purpose |

| Explore stories | ||||

| R4. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent ‘frames’, the perspective taken by the relevant management team according to differing levels of abstraction. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation is likely to be recursive (nested) with increasing granularity both horizontally and vertically. | Extended MPA | Capture perspectives | Small group conversations | |

| 6 Questions/SSM (Checkland) | Develop consensus on purpose and key high-level activities (‘what’ should be performed to achieve purpose) | |||

| Cognitive Maps | With respect to personal constructs (Kelly), seek to capture the organisational constructs | Kinston’s hierarchy of purpose | ||

| R11. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation can capture the feedbacks within the system, between the system and environment and within the environment. | SD | Causal Loop Diagrams | Informed by E&T Causal Textures | |

Progression Dimension | R3. Changes within the system (organisation) can be identified with regard to necessary activities as the organisation adapts to environmental changes. | SSM (Wilson) | Re-model CPTM with revised Root Definitions. Enables identification of activities no longer relevant and additional activities to be included. | May result from periodic re-visit of Purpose (6 Questions, SSM (Checkland) PQR. |

| Dependency Modelling | Map the internal and external dependencies contributing to the organisation working well | Specific events captured by CLD Scenario thinking/planning exercise | ||

| R5. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to determine holistically activities relevant to the agreed frames, but maintain logical dependencies and capture the richness of interaction. | SSM (Wilson) | Consensus Primary Task Model, either Enterprise Model or ‘W’ Decomposition | MPA, 6 Questions, Cognitive Maps | |

| Dependency models? | ||||

| R7. It should be possible to determine clusters of elements collaborating at short range as well as indicate the longer-range inter-relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | RACI analysis | Mapping to VSM | |

| VSM | Initial construction of relevant VSMs | Informed by SSM analysis | ||

| R8. Dependencies between elements must be captured. | SSM (Wilson) | RACI analysis | Mapping to VSM | |

| VSM | Initial construction of relevant VSMs | Informed by SSM analysis | ||

| Dependency Models? | ||||

| R9. Measures of performance can be identified. | SSM (Wilson) | Activity Analysis | Also consideration of metrics | |

| SD modelling might inform upstream and downstream points of measurement and optimisation | ||||

| R10. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent the non-linearity of relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | Logical dependencies between activities | ||

| VSM | Exploration of the environmental interactions and internal connections | Consideration of Angyal’s autonomy and heteronomy. | ||

| R11. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation can capture the feedbacks within the system, between the system and environment and within the environment. | SD | Causal Loop Diagrams | Informed by E&T Causal Textures | |

Transverse Dimension | R3. Changes within the system (organisation) can be identified with regard to necessary activities as the organisation adapts to environmental changes. | SSM (Wilson) | Re-model CPTM with revised Root Definitions. Enables identification of activities no longer relevant and additional activities to be included. | May result from periodic re-visit of Purpose (6 Questions, SSM (Checkland) PQR. |

| Dependency Modelling | Map the internal and external dependencies contributing to the organisation working well | Specific events captured by CLD Scenario thinking/planning exercise | ||

| R4. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent ‘frames’, the perspective taken by the relevant management team according to differing levels of abstraction. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation is likely to be recursive (nested) with increasing granularity both horizontally and vertically. | Extended MPA | Capture perspectives | Small group conversations | |

| 6 Questions/SSM (Checkland) | Develop consensus on purpose and key high-level activities (‘what’ should be performed to achieve purpose) | Small group conversations | ||

| Cognitive Maps | With respect to personal constructs (Kelly), seek to capture the organisational constructs | Kinston’s hierarchy of purpose | ||

| R6. Sub-organisations within the organisation or enterprise can be identified that have their own discrete properties (purpose). | SSM (Wilson) | Consensus Primary Task Model, either Enterprise Model or ‘W’ Decomposition | MPA, 6 Questions, Cognitive Maps | |

| Mapping to VSM | ||||

| VSM | Discrete VSMs within the VSM ‘set’ | Informing and informed by SSM | ||

| R7. It should be possible to determine clusters of elements collaborating at short range as well as indicate the longer-range inter-relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | RACI analysis | Mapping to VSM | |

| VSM | Initial construction of relevant VSMs | Informed by SSM analysis | ||

| R8. Dependencies between elements must be captured. | SSM (Wilson) | RACI analysis | Mapping to VSM | |

| VSM | Initial construction of relevant VSMs | Informed by SSM analysis | ||

| Dependency Model? | ||||

| R10. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent the non-linearity of relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | Logical dependencies between activities | ||

| VSM | Exploration of the environmental interactions and internal connections | Consideration of Angyal’s autonomy and heteronomy. | ||

| R11. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation can capture the feedbacks within the system, between the system and environment and within the environment. | SD | Causal Loop Diagrams | Informed by E&T Causal Textures | |

| R12. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must enable one to capture/integrate the environmental inter-relationships as well as internal peer–peer inter-relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | Modelling ‘System Served’ and detailed analysis of logical dependencies. | ||

| VSM | Exploration of the environmental interactions and internal connections | Consideration of Angyal’s autonomy and heteronomy. | ||

| Informed by E&T Causal Textures |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hilton, J. Building a Governance Reference Model for a Specific Enterprise: Addressing Social Challenges Through Structured Solution. Systems 2025, 13, 788. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090788

Hilton J. Building a Governance Reference Model for a Specific Enterprise: Addressing Social Challenges Through Structured Solution. Systems. 2025; 13(9):788. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090788

Chicago/Turabian StyleHilton, Jeremy. 2025. "Building a Governance Reference Model for a Specific Enterprise: Addressing Social Challenges Through Structured Solution" Systems 13, no. 9: 788. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090788

APA StyleHilton, J. (2025). Building a Governance Reference Model for a Specific Enterprise: Addressing Social Challenges Through Structured Solution. Systems, 13(9), 788. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13090788