Abstract

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in education highlights the growing need for AI literacy among K–12 teachers, particularly to enable effective human–machine cooperation. This study investigates Saudi K–12 educators’ AI literacy competencies across four key dimensions: awareness, ethics, evaluation, and use. Using a survey of 426 teachers and analyzing the data through descriptive statistics and structural equation modeling (SEM), this study found high overall literacy levels, with ethics scoring the highest and use slightly lower, indicating a modest gap between knowledge and application. The SEM results indicated that awareness significantly influenced ethics, evaluation, and use, positioning it as a foundational competency. Ethics also strongly predicted both evaluation and use, while evaluation contributed positively to use. These findings underscore AI literacy skills’ interconnected nature and point to the importance of integrating ethical reasoning and critical evaluation into teacher training. This study provides evidence-based guidance for educational policymakers and leaders in designing professional development programs that prepare teachers for effective and responsible AI integration in K–12 education.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly shaping education systems worldwide, offering new opportunities to personalize learning, enhance teaching efficiency, and support innovative practices. However, the successful adoption of AI in classrooms depends significantly on teachers’ ability to understand, evaluate, and apply AI technologies effectively [1]. In this context, AI literacy has emerged as a critical competency for educators, encompassing technical understanding, ethical awareness, critical appraisal, and practical application [2].

Recent literature has provided a conceptual foundation for AI literacy. Long and Magerko [3] proposed early definitions emphasizing understanding AI capabilities and limitations. These have since been expanded into more comprehensive models. Chiu et al. [4], for example, proposed a comprehensive AI literacy framework consisting of five interconnected dimensions—technology, impact, ethics, collaboration, and self-reflection—to support both cognitive and ethical engagement in AI education, while Pei et al. [5] emphasized institutional and contextual factors that influence AI literacy among preservice teachers. These developments reflect a growing consensus that AI literacy is not limited to technical fluency but also involves the ability to reflect on the social and ethical dimensions of AI, assess AI tools critically, and engage with them as collaborative partners in the learning process [6,7].

In the K–12 sector, teacher preparedness has become a focal point in discussions about integrating AI into schooling. Yet empirical studies show that many teachers feel underprepared to adopt AI tools in practice, citing gaps in training, ethical uncertainty, and challenges in evaluating the appropriateness of available technologies [8,9]. This raises significant concerns for countries aiming to modernize their educational systems in alignment with global trends.

Saudi Arabia presents a compelling case in this regard. National reform strategies such as Vision 2030 and the National Strategy for Data and AI (NSDAI) have placed a strong emphasis on building human capital through education and digital transformation [10,11]. These reforms prioritize equipping teachers with competencies that extend beyond general digital skills to include AI-specific literacy. While these national priorities are clearly articulated, there is little empirical evidence assessing the extent to which K–12 teachers in Saudi Arabia possess these competencies. Most existing studies have concentrated on higher education settings [12,13,14], leaving a notable research gap in the K–12 context. This gap hampers efforts to tailor professional development programs, design targeted curricula, and formulate policies that address the actual needs of school educators.

To address this limitation, the present study investigates Saudi K–12 teachers’ self-perceived AI literacy. This study offers a theoretical contribution by conceptualizing awareness as the foundational dimension of AI literacy, influencing how teachers develop ethical reasoning, critical evaluation, and practical classroom use of AI tools. The aim is to provide data-driven insights that can inform educational strategies and support the country’s broader transformation goals. Accordingly, this study aims to explore how competent Saudi K–12 teachers are in AI literacy across the dimensions of awareness, ethics, evaluation, and use, and investigates the interrelationships among these competencies, positioning awareness as a foundational driver of the others. As such, this study is guided by the following two research questions:

- How competent do Saudi K–12 teachers perceive themselves to be in AI literacy across the factors of awareness, ethics, evaluation, and use?

- What are the interrelationships among AI literacy factors (awareness, use, evaluation, and ethics) among Saudi K–12 teachers?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Human–Machine Cooperation in Education

Human–machine cooperation in education refers to the collaborative interaction between educators and AI technologies to achieve shared teaching and learning goals. Unlike automation, which replaces human effort, this approach leverages the unique strengths of both humans and AI systems. Educators provide the creativity, emotional intelligence, and contextual knowledge needed to design and implement effective teaching strategies, while AI can assist by automating administrative functions and supporting data-driven educational decisions [15]. This collaboration aligns with the broader educational shift toward personalized learning and differentiated instruction. For example, AI tools can provide real-time assessments and adaptive feedback to support diverse student needs, creating an environment that promotes engagement and improved learning outcomes [16]. In Sweden, extant studies have demonstrated how AI fosters human–machine cooperation by improving both instructional practices and administrative efficiency in K–12 contexts [9].

AI tools play a complementary role in education, enhancing traditional teaching methods rather than replacing them. For example, AI-powered platforms can analyze individual learning patterns, enabling teachers to adapt lesson plans and resources to better suit student needs [17,18]. In Saudi Arabia, efforts to integrate AI into K–12 classrooms have focused on using AI to design customized teaching materials, thereby fostering inclusivity and efficiency [19]. Moreover, AI can help automate routine tasks, such as grading assignments and managing administrative workflows. This allows teachers to focus on higher-order tasks, such as mentoring students and designing student-centered learning activities [20]. However, extant studies indicate that these tools’ success depends significantly on teachers’ AI literacy competencies, particularly in areas such as ethical evaluation and appropriate use [16]. Addressing these competencies through professional development is essential to maximizing AI’s benefits to education.

2.2. AI Literacy in K–12 Education

AI literacy increasingly is being recognized as a critical competency in modern education, particularly in the K–12 education context [21]. The term AI literacy encompasses a range of knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to understand, interact with, and critically evaluate AI technologies. Ng et al. [22] defined AI literacy as the ability to engage with AI systems in a meaningful way, including understanding their capabilities, limitations, and ethical implications. Similarly, Chiu et al. [4] described AI literacy as a multidisciplinary construct that integrates technical understanding, ethical considerations, and collaborative and reflective practices, which are essential for effective navigation in an AI-driven world.

The integration of AI literacy into K–12 education is crucial for preparing students to thrive in an AI-driven future. AI technologies are reshaping various aspects of education, from personalized learning to administrative efficiency [3]. As noted by Eguchi et al. [23], fostering AI literacy through culturally responsive approaches can enhance students’ critical thinking, problem-solving, and ethical reasoning. Holmes and Tuomi [24] further emphasize the educator’s role in integrating AI meaningfully into learning environments. As Chiu and Sanusi [25] argued, educators first must possess a foundational understanding of AI concepts to integrate these technologies into their teaching practices effectively. Extant studies such as Crompton et al. [20] have emphasized that AI literacy not only enhances educators’ instructional capabilities but also empowers them to address challenges such as misinformation and algorithmic bias in the classroom.

Zhao et al. [26] examined AI literacy among primary and middle school teachers in China and found significant gaps in educators’ evaluation skills and ethical considerations, emphasizing the need for targeted professional development program. This aligns with Tenberga and Daniela [7], who utilized self-assessment tools to measure AI literacy competencies among teachers in Latvia. Their results highlighted disparities in technical proficiency and the ability to assess AI systems critically, underscoring tailored training interventions’ importance. Similarly, Sperling et al. [27] conducted a scoping review of AI literacy in teacher education, revealing that while many programs address technical skills, ethical and evaluative competencies often remain underemphasized. Notably, Yim and Su [28] conducted a scoping review of AI learning tools in K–12 education. Their findings highlighted AI-integrated curricula’s potential to foster critical AI literacy competencies but also pointed out the lack of standardized metrics for evaluating these tools’ effectiveness.

While research on AI literacy in K–12 education is growing globally, most studies have been concentrated in countries with established AI education strategies. This has resulted in a noticeable gap in the literature from underrepresented or rapidly developing regions. To address this, the next chapter shifts focus to the regional context of Saudi Arabia, examining how global frameworks and findings align—or diverge—from national policies, teacher training initiatives, and the realities of classroom implementation within the Kingdom.

2.3. Global and Regional Perspectives on AI Literacy

Globally, AI literacy increasingly is recognized as a critical component of 21st century education, equipping both teachers and students with the competencies needed to understand, evaluate, and use AI technologies responsibly. Countries such as the United States, South Korea, and China have launched comprehensive national initiatives to embed AI literacy across educational systems. These programs indicate a growing consensus that fostering AI literacy is essential not only for digital readiness but also for civic and ethical participation in AI-mediated societies. In the United States, AI education efforts are being driven by organizations such as Artificial Intelligence for Kindergarten Through 12th Grade (AI4K12), which provides guidelines for integrating AI concepts into kindergarten through high school [29]. These initiatives emphasize computational thinking, data literacy, and ethical reasoning, ensuring that educators are not just passive adopters of AI tools but also critical facilitators of AI understanding. Professional development workshops, such as those funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), help teachers design AI-focused lessons and integrate them into STEM curricula [30]. These efforts align with broader goals for developing AI literacy competencies among educators and learners [3].

In China, the Ministry of Education has prioritized AI in its national strategic plans, investing in teacher training and curriculum development at all school levels. Zhao et al. [26] examined the interrelationships among four dimensions of AI literacy—knowing and understanding AI, applying AI, evaluating AI applications, and AI ethics—among primary and middle school teachers. Their findings indicate that the ability to apply AI significantly influences the other dimensions, underscoring the importance of practical application skills in enhancing teachers’ overall AI literacy. This empirical evidence supports the assertion that robust teacher training directly influences successful AI curriculum implementation.

Likewise, South Korea has increasingly emphasized AI education in schools, with national initiatives supporting curricula and teacher preparation programs that promote both technical understanding and socioethical awareness. These initiatives focus on developing key competencies, including AI conceptual understanding, data literacy, and ethical awareness, with emerging efforts to integrate these elements across various subject areas. In this context, Kim and Kwon [31] examined the self-perceived AI competencies of elementary school teachers, focusing on these core domains. Their findings revealed generally low to moderate competency levels, highlighting the urgent need for targeted professional development. The study emphasized that educators must possess a well-rounded understanding of AI concepts and ethical implications to teach effectively in AI-integrated environments. This underscores the importance of competency-based teacher preparation programs in supporting national AI education goals.

Moreover, countries such as Hong Kong have adopted project-based learning (PBL) to enhance student engagement and the real-world application of AI knowledge. Kong et al. [32] reported that in senior secondary classrooms, students collaboratively design AI solutions to community problems, thereby promoting experiential learning and critical thinking. The study found that students who completed a 14 h AI literacy course demonstrated improved problem-solving abilities, enhanced metacognitive strategies, and a stronger understanding of AI ethics. Through the PBL approach, students critically reflected on the ethical use of AI while applying it to real-world contexts, offering a model for holistic AI literacy development in secondary education.

Saudi Arabia actively is advancing AI literacy as part of its national digital transformation and Vision 2030 strategy, which aims to diversify the economy through investment in technology and innovation. The Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority (SDAIA) has taken the lead in positioning the Kingdom as a regional hub for AI development and education. Although no national AI curriculum has been integrated into K–12 yet, the government has initiated several capacity-building programs and partnerships focused on teacher training, awareness, and ethical understanding of AI. For example, SDAIA’s AI Talent Development Program, in collaboration with global universities such as MIT and Stanford, aims to upskill thousands of Saudi citizens—including educators—in data science and AI. The National Strategy for Data and AI (NSDAI) explicitly calls for AI skills inclusion in school and university curricula [11]. However, extant studies (e.g., [19]) indicate that AI literacy competence among K–12 teachers remains limited, with some calling for national teacher development frameworks to promote sustainable AI integration in education.

While the country is actively pursuing digital transformation under Vision 2030, systematic efforts to measure K–12 teachers’ AI literacy competencies, a critical foundation for successful AI integration, are notably lacking. Saudi Arabia’s focus on AI adoption primarily has been policy-driven, with less emphasis placed on teacher preparedness or competency evaluation [12]. Extant studies have found that while many Saudi K–12 teachers have expressed interest in integrating AI tools into their classrooms, they often lack the necessary competencies and institutional support [33]. A recent 2024 study examining Saudi teachers’ perspectives on integrating AI-powered technologies in K–12 education identified key challenges, including limited AI literacy and a lack of professional development opportunities tailored to AI integration [19].

Furthermore, research on chatbot adoption among K–12 teachers in Saudi Arabia found that AI literacy significantly influences teachers’ acceptance and utilization of AI tools in education. The study emphasized the need for specialized workshops and professional communities to enhance AI literacy among educators [33]. Other studies suggest that many teachers lack foundational AI literacy, including awareness, ethical considerations, and evaluation skills that are critical for the responsible adoption of AI in classrooms [34]. This underscores the urgent need for a competency-based approach to ensure that teachers are adequately equipped to handle AI tools [12]. Without data-driven insights into teachers’ current levels of awareness, ethics, evaluation, and practical use, policymakers and education leaders cannot design targeted training programs [16].

These challenges—particularly limited teacher preparedness, low awareness of AI ethics, and weak evaluative capacity—underscore the need for a structured framework tailored to the Saudi K–12 context. The next chapter introduces this conceptual framework, grounded in both international research and the specific needs identified in Saudi education.

3. Conceptual Framework

This section introduces a conceptual framework to examine AI literacy among Saudi K–12 teachers. The selected dimensions—awareness, ethics, evaluation, and use—emerge from documented gaps in the Saudi context, particularly in teachers’ preparedness, ethical understanding, and critical assessment of AI tools [33,34]. These dimensions are also consistent with international models of AI literacy that emphasize the multifaceted nature of AI competence, including technical knowledge, ethical reasoning, and pedagogical application [4,22]. By integrating both global insights and local educational needs, this study adopts the four-dimensional framework proposed by Wang et al. [35], comprising awareness, ethics, evaluation, and use, to guide the investigation.

While existing models often treat AI literacy dimensions as parallel constructs, this study adopts a different perspective by conceptualizing awareness as a foundational competency that informs teachers’ ethical reasoning, critical evaluation, and classroom use of AI. This framing reflects both the developmental nature of professional learning and the ethical imperatives emphasized in the Saudi context. In the Saudi K–12 context, current educational initiatives (e.g., Vision 2030, SDAIA’s AI Talent Development Program) emphasize the ethical awareness, responsible use, and critical understanding of AI systems rather than advanced technical development or interdisciplinary design. Moreover, recent studies in the region [33,34] indicate that teachers often face challenges in the basic awareness, ethical discernment, and evaluation of AI tools, which further supports the relevance of these four dimensions.

The following literature review supports this framework by examining the prior research that establishes the interrelationships among these constructs in educational settings.

Awareness is a foundational element of AI literacy that strongly influences educators’ adoption and integration of AI tools. Ng et al. [22] defined awareness as the ability to recognize AI systems in daily life and comprehend their role in shaping human interactions and decision-making processes. For educators, awareness includes knowledge about how AI is used in educational technologies, such as adaptive learning platforms and administrative tools, as well as an understanding of these systems’ potential benefits and risks. Extant studies consistently have found that when educators possess a clear understanding of AI technologies—how they function, their benefits, and their limitations—they are more likely to use these tools effectively in their classrooms. Ng et al. [22] emphasized that awareness creates a sense of familiarity and confidence, reducing anxieties about AI’s complexities and encouraging exploration. Similarly, Zhao et al. [26] argued that awareness demystifies AI tools, empowering educators to recognize their potential for enhancing teaching and learning. For example, educators who are aware of AI’s ability to personalize learning can leverage it to support differentiated instruction.

Güneyli et al. [36] explored teacher awareness of artificial intelligence (AI) in education through a case study conducted in Northern Cyprus, revealing that teacher awareness—particularly when grounded in applied experience—is a key determinant in the effective adoption and integration of AI tools in educational settings. Chiu et al. [4] added that awareness is a critical determinant during the initial stages of AI adoption, facilitating smoother transitions from traditional methods to AI-enhanced practices. Other studies have similarly highlighted awareness as a crucial factor in AI adoption among educators [37,38]. This body of literature collectively underscores the pivotal role of awareness in fostering educators’ willingness and capability to integrate AI tools into their teaching strategies. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Awareness of AI tools exerts a positive impact on their use among K–12 teachers.

Teachers with a strong awareness of AI tools are significantly better-equipped to evaluate these tools critically. Awareness provides educators with the conceptual knowledge needed to assess AI applications’ reliability, accuracy, and appropriateness in educational contexts. Ng et al. [22] argued that awareness lays the groundwork for evaluative skills by familiarizing teachers with the operational principles and potential biases inherent in AI systems. This knowledge enables them to scrutinize AI tools more effectively, thereby ensuring alignment with pedagogical objectives. Chiu et al. [4] and Alammari [39] emphasized that awareness helps educators identify various AI tools’ strengths and limitations, empowering them to make informed decisions about their use. For example, a teacher aware of data privacy concerns in AI systems is more likely to evaluate these systems critically for compliance with ethical and legal standards. Sperling et al. [27] found that teachers with heightened awareness are more discerning when selecting AI tools, focusing on their educational value and potential to address specific classroom challenges. Zhao et al. [26] also found that awareness positively impacts educators’ ability to assess the scalability and long-term implications of adopting AI tools. Together, these studies demonstrate that awareness serves as the cognitive foundation for developing robust evaluation skills. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Awareness of AI tools exerts a positive impact on their evaluation among K–12 teachers.

Awareness of AI technologies significantly influences educators’ ethical decision-making, enabling them to navigate complex issues, such as bias, equity, and privacy. Ng et al. [22] asserted that awareness fosters a deeper understanding of AI’s societal and ethical implications, providing educators with the tools to address these challenges responsibly. For example, a teacher who understands how AI algorithms function is better-positioned to recognize potential biases and advocate for equitable practices in their application. UNESCO [40] underscored that awareness is a prerequisite for developing ethical literacy, as it equips educators with the knowledge needed to identify and mitigate ethical risks associated with AI tools. Eguchi et al. [23] found that teachers who are aware of the potential for misuse of AI technologies are more likely to adopt preventive measures to protect student data and ensure transparency in AI-driven decision-making. Holmes and Porayska-Pomsta [15] added that awareness of ethical issues enhances educators’ ability to foster discussions among students about AI ethics, promoting a culture of accountability and social responsibility. These studies collectively have found that awareness acts as a catalyst for ethical competence, guiding educators in making informed and morally sound decisions about AI integration. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Awareness of AI tools makes a positive impact on their ethics among K–12 teachers.

Ethical considerations significantly enhance teachers’ ability to evaluate AI tools, particularly for identifying biases, ensuring fairness, and maintaining transparency. Ng et al. [22] argued that an understanding of ethical principles provides educators with a moral framework for assessing AI systems critically. This includes evaluating whether AI tools align with the values of inclusivity and equity, which are essential in diverse educational contexts. Chiu et al. [4] found that ethical awareness allows educators to scrutinize AI tools for potential harm, such as discriminatory outcomes or breaches of privacy. UNESCO [40] supports this perspective, emphasizing that ethical literacy is integral to the evaluation process, ensuring that AI tools meet both educational and societal standards. Eguchi et al. [23] added that ethical considerations strengthen the evaluation process by encouraging educators to critically assess the broader societal and pedagogical implications of adopting AI in classrooms. These studies collectively demonstrate that ethics and evaluation are deeply intertwined, with ethical literacy serving as a foundation for responsible and informed assessments of AI technologies. Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The ethical aspects of AI tools make a positive impact on their evaluation among K–12 teachers.

Ethical considerations are pivotal in shaping educators’ decisions to adopt and use AI tools responsibly. Ng et al. [22] found that teachers with a strong understanding of AI ethics are more likely to implement these technologies in ways that promote fairness, transparency, and student well-being. Ethical literacy ensures that educators prioritize tools that respect data privacy, avoid reinforcing biases, and support equitable learning opportunities. Holmes and Porayska-Pomsta [15] argued that ethical frameworks guide teachers in selecting AI tools that align with both societal values and educational integrity. For example, an educator aware of data privacy concerns may choose AI platforms with robust security measures to ensure that student information is protected. Alotaibi and Alshehri [34] added that ethical considerations prevent misuse of AI tools, fostering a culture of accountability in their application. Sperling et al. [27] emphasized that teachers with strong ethical awareness are more likely to advocate for policies and practices that support responsible AI integration, ensuring that these technologies are used for the benefit of all students. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

AI tools’ ethical aspects make a positive impact on their use among K–12 teachers.

Teachers’ ability to evaluate AI tools critically impacts their effective use in educational contexts. Evaluation allows educators to assess whether an AI tool aligns with their instructional goals, supports diverse learning needs, and operates reliably. Ng et al. [22] argued that evaluation skills enable teachers to select tools that are both pedagogically sound and technically robust, ensuring that their use contributes positively to student outcomes. For example, an educator with strong evaluation skills might prioritize AI tools with adaptive learning features to cater to students with varying proficiency levels. Eguchi et al. [23] emphasized that evaluation is crucial when identifying potential pitfalls in AI applications, such as biases in algorithmic decision-making or limitations in data processing. Teachers who evaluate tools critically are better-positioned to mitigate these issues, thereby ensuring responsible implementation. Zhao et al. [26] found that evaluation skills not only improve the effectiveness of AI tool usage but also enhance educators’ confidence in integrating advanced technologies into their classrooms. Chung et al. [41] highlighted that evaluation is a foundational component of AI literacy, as it equips teachers with the ability to interpret diagnostic feedback and performance metrics. This evaluative capacity empowers K–12 educators to make informed instructional decisions, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness and confidence in their use of AI tools. Together, these studies underscore evaluation’s essential role in bridging the gap between theoretical understanding and practical application. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Evaluation of AI tools makes a positive impact on their use among K–12 teachers.

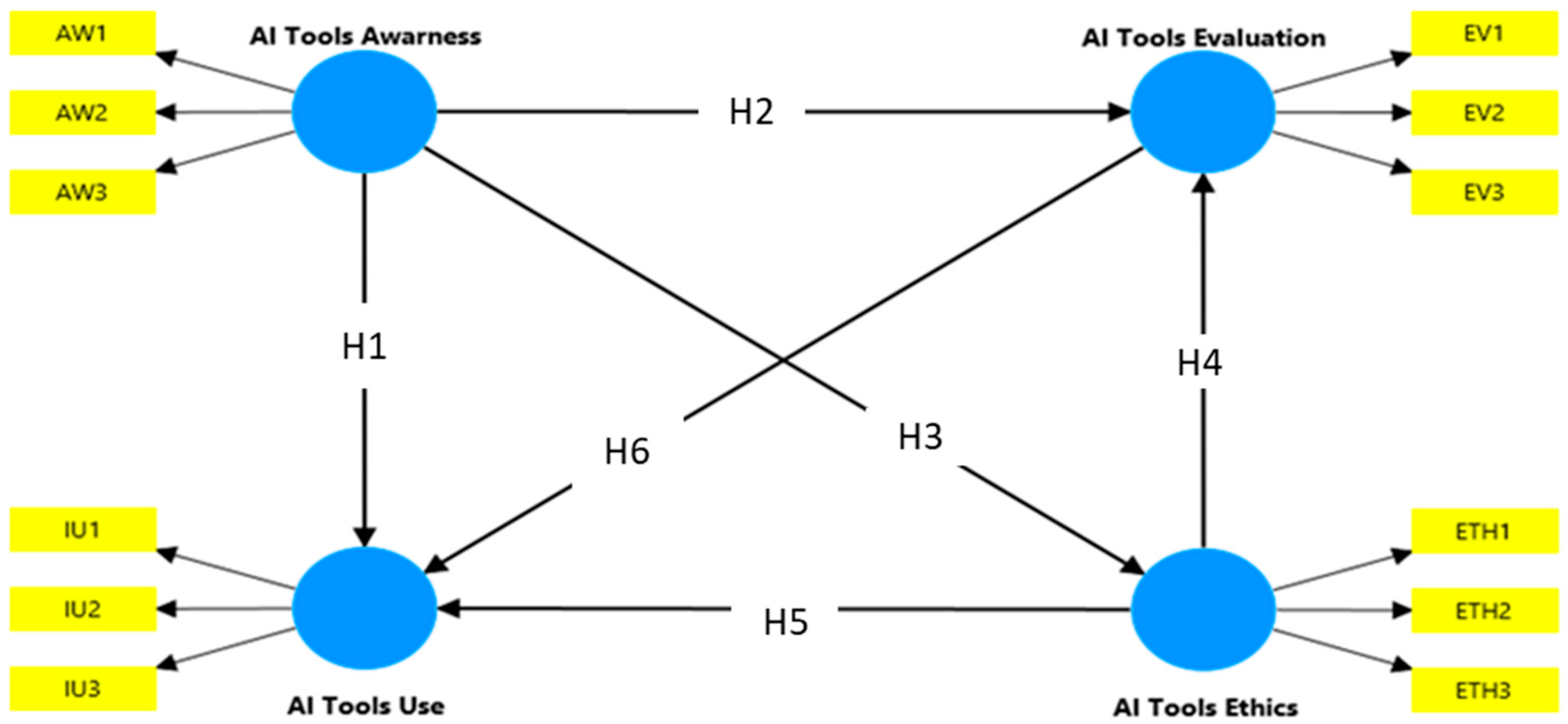

Figure 1 presents the proposed model of the interrelationships among the AI literacy competence constructs.

Figure 1.

The proposed research model.

4. Methods

4.1. Data Collection and Participants

Data collection for this study was conducted from October to December 2023 after obtaining ethical approval and informed consent from participants. The survey was distributed through social media platforms (e.g., WhatsApp and Telegram) to maximize accessibility and reach K–12 teachers across Saudi Arabia. Leveraging these platforms facilitated inclusion of diverse teacher demographics, allowing for comprehensive data collection representative of various regions and educational contexts within the country. K–12 teachers were invited to complete the online survey at their convenience voluntarily, with submissions recorded digitally to streamline data management and analysis.

Table 1 presents the demographics of the participants, comprising 77.5% female educators. The largest age groups were 30–39 (32.4%) and 40–49 (32.6%), representing a predominantly mid-career workforce. Educators with less than five years of experience comprised the largest group (28.6%), followed by those with 11–20 years (25.4%), ensuring a mix of early-career and experienced professionals. Elementary and high school teachers dominated the sample (32.9% each), while preschool educators were the smallest group (6.8%). This diversity enriched the study by encompassing varied teaching contexts and experiences.

Table 1.

Sample outline (N = 426).

4.2. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including the mean and standard deviation, to address Research Question 1, while partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) via SmartPLS 4.0 was employed to address Research Question 2.

4.3. Measurement

This study used a 21-item preexisting survey questionnaire to examine participants’ perceptions of the four constructs illustrated in the research model (Figure 1). To ensure clarity and appropriateness for the target population, three educational technology experts reviewed the Arabic-translated version of the questionnaire. Based on their feedback, minor modifications were made to the language and terminology to improve clarity and contextual alignment with K–12 education in Saudi Arabia. These adjustments were limited to phrasing and did not alter the original meaning or content of the items. In addition, a small pilot pretest (n = 10) was conducted to confirm face validity and ensure the linguistic and contextual clarity of the survey items for teacher participants. The survey began with demographic questions, followed by items designed to measure participants’ perceptions through a five-point Likert scale. Four primary constructs—awareness, use, evaluation, and ethics, each assessed with three items—were adapted from Wang et al. [35] to align with this study’s objectives (See the survey questionnaire in Appendix A).

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Analysis of AI Literacy Competency

The descriptive statistics for the variables awareness, use, evaluation, and ethics provide valuable insights into AI literacy factors among the 426 K–12 teachers surveyed. These results shed light on teachers’ perceptions and competencies related to AI tools across various constructs.

As presented in Table 2, the awareness construct’s M score was 4.0415, indicating that participants generally reported high levels of awareness regarding AI tools. This suggests that most teachers are familiar with the concept of AI and its potential applications in educational contexts. The SD of 0.691 indicates moderate consistency in responses, implying that most participants share similar levels of awareness. This relatively low variability indicates that the teachers have a shared understanding of AI literacy’s foundational aspects. Furthermore, the use construct’s M score was slightly lower, at 3.94, which still represents a relatively high level of reported use of AI tools but suggests a modest gap compared with awareness. The SD of 0.731 is higher than that for awareness, indicating greater variability in how teachers actually use AI tools in their teaching practices. This variability could indicate differences in access to resources, comfort with technology, or training opportunities among the participants.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of AI literacy competency (N = 426).

The M score of 4.00 on the evaluation construct indicates that participants perceive themselves as competent in critically assessing AI tools. This aligns closely with their reported awareness levels, suggesting a connection between understanding AI concepts and the ability to evaluate their use effectively. The SD of 0.730, comparable to that of use, indicates a moderate spread in evaluation skills among the sample, indicating some variability in teachers’ abilities to assess AI tools critically. Ethics scored the highest M value, at 4.11, indicating that ethical considerations are a strong focus among the participants, i.e., teachers seem to place significant importance on understanding and addressing the ethical issues related to AI, such as data privacy, fairness, and bias. The SD of 0.651 was the lowest among the variables, indicating that responses were the most consistent for this dimension. This uniformity suggests a shared recognition of the importance of ethical awareness in the AI literacy context.

Overall, all variables exhibited high mean values (above 3.9), suggesting that K–12 teachers in the sample generally reported positive perceptions of their AI literacy competence. The relatively low variability in ethics compared with other constructs implies a more uniform consensus on the importance of ethical considerations in AI literacy. However, the slightly lower mean for use indicates a potential gap between theoretical knowledge (awareness and evaluation) and practical application (use) of AI tools.

5.2. Interrelationship Analysis of AI Literacy Factors

Following Hair et al. [42], the analysis comprised two stages: evaluating the measurement model for reliability and validity and assessing the structural model to test the six hypotheses. As presented in Table 3, the results from the measurement model validation illustrate strong construct reliability and validity. Standardized indicator loadings ranged from 0.78 to 0.91, comfortably surpassing the minimum recommended value of 0.7 [42]. This confirms that the items are reliable indicators of their respective constructs. Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) values also demonstrated high internal consistency, with all constructs achieving α and CR values above 0.8. Such results underscore the robustness of the measurement scales used in this study. The average variance extracted (AVE) values, ranging from 0.62 to 0.80, further affirmed the constructs’ convergent validity, as all values exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.5. These findings validate the measurement model, confirming that the constructs are appropriately represented and reliable for further analysis.

Table 3.

Analysis of the measurement model.

Table 4 demonstrates the results from the discriminant validity testing, which ensures that each construct in the model is empirically distinct. Using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) method, the results reveal that the square roots of the AVE values for all constructs exceeded their intercorrelations. Moreover, all HTMT values fell below the critical threshold of 0.85, indicating clear distinctions between constructs. These findings reinforce the model’s validity, confirming that each construct measures a unique dimension of the theoretical framework.

Table 4.

Analysis of discriminant validity.

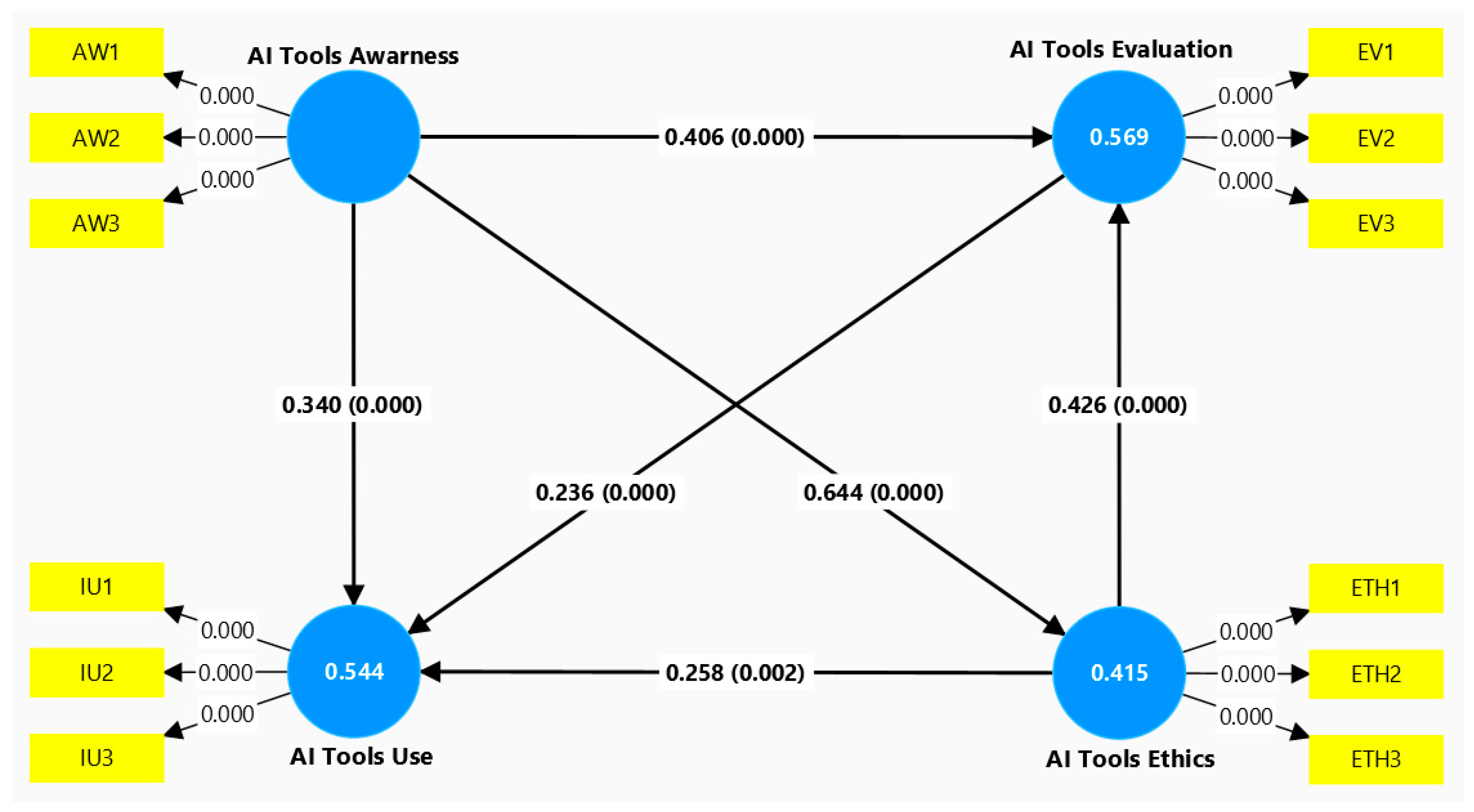

The structural model analysis, detailed in Table 5 and Figure 2, evaluates the relationships between constructs and tests the study’s hypotheses. Significant path coefficients (β) were identified for several relationships, including awareness positively predicting use (β = 0.340, p < 0.001), evaluation (β = 0.406, p < 0.001), and ethics (β = 0.644, p < 0.001), thereby supporting H1, H2, and H3, respectively. Evaluation also was found to influence use significantly (β = 0.236, p < 0.001), thereby supporting H4. Ethics emerged as a significant predictor of both use (β = 0.258, p < 0.002) and evaluation (β = 0.426, p < 0.001), thereby supporting H5 and H6. The model’s predictive strength was evidenced by the R2 values for use (0.544) and evaluation (0.569), indicating moderate predictive power [43]. Furthermore, the Q2 values of 0.442 for use and 0.461 for evaluation confirmed strong predictive relevance, suggesting that the model effectively explains and predicts relationships within the theoretical framework.

Table 5.

Hypothesis testing result.

Figure 2.

Standardized path coefficient results.

6. Discussion

This study investigated AI literacy level among Saudi K–12 teachers and examined the interrelationships among four key AI literacy dimensions: awareness, ethics, evaluation, and use. The results offer valuable insights into how teachers are positioned to engage with AI technologies and how these competencies interact to support responsible human–machine cooperation in educational contexts.

In response to the first research question, the descriptive findings indicate that Saudi teachers reported moderately high levels of AI literacy across all four domains. Ethics (M = 4.11) and awareness (M = 4.04) emerged as the most developed competencies, followed closely by evaluation (M = 4.00), while use (M = 3.94) scored the lowest. This pattern suggests that while teachers possess a strong conceptual understanding of AI and its ethical dimensions, their confidence and experience using AI tools practically in classrooms remain somewhat limited. These results are consistent with international findings, such as Zhao et al. [26], who reported that Chinese teachers similarly exhibited high levels of ethical awareness but lacked hands-on familiarity with AI tools. Likewise, Tenberga and Daniela [7] found that Latvian educators scored lower on practical AI use compared to conceptual understanding, indicating a global gap between awareness and implementation.

In addressing the second research question, the SEM revealed significant and theoretically coherent relationships between AI literacy dimensions. First, awareness significantly predicted the use of AI tools (β = 0.340, p < 0.001), supporting the notion that teachers who are more informed about AI technologies are more likely to adopt them in practice. This finding aligns with the literature emphasizing awareness as a gateway to technology integration [4,5,8]. Awareness helps reduce uncertainty and builds confidence to try out AI tools, thereby encouraging experimentation and adoption [27].

In addition to influencing use, awareness also was found to make a strong impact on teachers’ ability to evaluate AI tools (β = 0.406, p < 0.001). This relationship indicates that teachers who understand AI’s operational principles and potential risks are better-equipped to assess its educational value critically. This supports Sperling et al. [27], who noted that awareness forms the cognitive basis for evaluative judgement, allowing teachers to discern AI applications’ appropriateness in relation to specific pedagogical goals. Awareness is not just informational; it activates reflective thinking that leads to better decision-making about AI use in the classroom.

The strongest relationship identified in this study was between awareness and ethics (β = 0.644, p < 0.001), emphasizing that conceptual familiarity with AI also underpins ethical literacy. Teachers who are aware of how AI works are more likely to recognize issues of bias, data privacy, and algorithmic fairness. This finding is particularly relevant given the ethical risks posed by uncritical AI use in educational contexts. UNESCO [40] and Holmes and Porayska-Pomsta [15] both assert that awareness is essential for ethical reasoning, as it enables teachers to evaluate AI not only as a tool but also as a sociotechnical system with real-world consequences. In the Saudi context, in which formal AI policies for K–12 education are still emerging, this link between awareness and ethics underscores the importance of building foundational knowledge as a step toward responsible practice.

The results also confirm that ethics significantly influences evaluation (β = 0.426, p < 0.001). This relationship illustrates that ethical reasoning enables teachers to assess AI systems more holistically, considering not only technical functionality but also issues such as fairness, transparency, and inclusivity. These findings are consistent with Chiu et al. [4] and Eguchi et al. [23], who argued that ethical awareness enhances the quality and rigor of technology assessment. Educators with a strong ethical grounding are more likely to question the implications of AI implementation and evaluate tools in line with professional and societal values.

Furthermore, ethics also were found to predict AI use directly (β = 0.258, p = 0.002), suggesting that teachers who feel ethically competent are more confident in applying AI in their classrooms. This builds on extant research by Sperling et al. [27], who found that ethical literacy reduces anxiety about using emerging technologies. Teachers who understand data protection principles or bias mitigation strategies may be more comfortable integrating AI tools, knowing they can use them responsibly and safely.

Finally, this study confirmed a significant link between evaluation and use (β = 0.236, p < 0.001), in which teachers who can evaluate AI tools critically are more likely to use them effectively and meaningfully in practice. This aligns with Chung et al. [41], who demonstrated that critical evaluation supports intentional, informed use of AI, as opposed to trial-and-error or passive adoption. Teachers who can assess AI tools’ pedagogical and ethical suitability are better-positioned to align these tools with curricular goals and student needs.

While this study focused on self-reported competencies, the findings imply clear application pathways in real-world classrooms. For instance, a teacher with strong ethical literacy may critically assess the fairness of an adaptive learning system that personalizes instruction based on potentially biased data. Similarly, a teacher with high awareness might question the data handling policies of an AI-driven homework-grading tool before adopting it in their class. Teachers with strong evaluative skills may opt out of opaque algorithmic tools, instead choosing platforms with explainable AI models that align with instructional transparency.

In addition to these practical implications, the study offers a theoretical contribution by conceptualizing awareness as a foundational AI literacy competency that significantly influences ethics, evaluation, and use. This structure departs from earlier models—such as Ng et al. [22]—which tend to treat these dimensions as parallel rather than sequential. The significant path coefficients in our model suggest a developmental progression: teachers first develop awareness of AI technologies, which then informs their ethical reasoning, critical evaluation, and eventual classroom use. This stage-based interpretation provides a more dynamic understanding of how AI literacy evolves in professional practice and offers a practical framework for designing targeted training programs that scaffold competencies in a progressive manner.

6.1. Implications

This study’s findings pose meaningful implications for educational practice, policy development, and future research directions, particularly as nations such as Saudi Arabia accelerate digital transformation under initiatives such as Vision 2030. At the practical level, the results underscore the urgent need to design and implement comprehensive, competency-based professional development programs for K–12 teachers. While teachers demonstrated relatively high levels of awareness and ethical sensitivity, their comparatively lower scores in practical use and evaluation signal a critical skills gap that may hinder effective integration of AI into teaching and learning environments. This suggests that current training models may overemphasize theoretical exposure to AI concepts while underdelivering on applied skill-building.

To address this, professional development must move beyond introductory awareness sessions to provide immersive, hands-on experiences that allow teachers to engage directly with AI tools in pedagogically meaningful contexts [5]. This includes integrating scenario-based learning that simulates ethical dilemmas, critical case analysis exercises that examine real-world implications of algorithmic bias and privacy breaches, and guided experimentation with classroom-ready AI platforms, such as intelligent tutoring systems, automated grading tools, or adaptive learning software. Such programs should be differentiated based on teachers’ prior experience, subject area, and educational level to ensure relevance and engagement. Moreover, teacher training programs should be tailored to the practical use of AI in schools, supported by diverse experts sharing their knowledge, and designed as ongoing initiatives with continuous mentoring, peer collaboration, and embedded feedback mechanisms within school communities [44]. Without these measures, even high levels of theoretical AI literacy may fail to translate into confident and ethical classroom application.

At the policy level, this study highlights the necessity of embedding AI literacy competencies into national teacher qualification frameworks and certification standards. The statistically significant interrelationships among awareness, ethics, evaluation, and use reinforce the idea that these are not standalone constructs and actually form an integrated skillset essential for modern teaching. Therefore, policymakers must recognize that any initiative to introduce AI in education will be incomplete if it focusses solely on technological infrastructure or digital tools without equally investing in teacher readiness. This study’s implications suggest that national AI-in-education strategies must include structured pathways for teacher development that highlight AI literacy’s multidimensional nature.

Furthermore, as ethics emerged as a key predictor of both evaluation and use, policy documents should articulate clear ethical guidelines and protocols for AI integration within schools. This includes data protection policies tailored to educational contexts, frameworks for algorithmic transparency, and standards for equitable AI implementation across various socioeconomic and geographic contexts. In line with this, educational authorities should consider developing national AI literacy benchmarks or certification schemes—potentially modeled after international frameworks, such as UNESCO’s AI Competency Framework for Educators [45]—that emphasize ethical, legal, and societal dimensions alongside technical skills.

Theoretically, this study’s results emphasize that AI literacy among teachers should be understood as a multidimensional professional competency that integrates cognitive understanding, ethical awareness, critical evaluation, and practical application. The significant interrelationships found among these constructs suggest that AI literacy cannot be developed through isolated technical training alone. Instead, it evolves through interconnected learning experiences that foster both reflective judgement and applied practice. This supports emerging theoretical perspectives that position AI literacy as part of teachers’ evolving digital competence, shaped not only by access to technology but also by values, pedagogical goals, and contextual realities within the classroom. Such a perspective encourages future research that investigates how these dimensions co-develop over time and how they can be supported through holistic professional learning models.

Moreover, this study invites further theoretical development by highlighting the interplay between conceptual understanding and ethical application. It raises questions about how AI literacy evolves over time, how contextual factors such as school culture or leadership support influence its development, and what interventions are most effective for building lasting competencies. Future research should also explore how these AI literacy competencies manifest in specific classroom interactions—such as lesson planning with intelligent tutoring systems, managing algorithmic bias in adaptive tools, or making ethical decisions when using automated feedback generators. Investigating how teachers operationalize these skills will help bridge the gap between self-perceived literacy and actual pedagogical practice, aligning more closely with Vision 2030’s emphasis on practical, real-world readiness. Future research should investigate these dynamics using longitudinal designs, mixed-methods approaches, or intervention-based studies to capture the complexities of how teachers internalize and operationalize AI literacy in real educational contexts.

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

While this study provides valuable insights into K–12 teachers’ AI literacy competence in Saudi Arabia, several limitations should be acknowledged, each offering directions for future research. First, the use of a cross-sectional survey design limits the ability to determine causal relationships or track changes in AI literacy over time. To address this, future studies should adopt longitudinal or repeated-measures designs to monitor how teachers’ AI literacy develops through ongoing professional development, technological advancements, or policy interventions.

Second, the study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to social desirability bias—particularly in sensitive domains such as ethical awareness and AI use. Although the instrument employed was previously validated [35], the potential for over- or underreporting remains. Moreover, the exclusive use of a quantitative survey approach limited the ability to explore the nuanced perspectives, contextual factors, and lived experiences that shape teachers’ engagement with AI. Future research could incorporate complementary methods—such as direct assessments, classroom observations, digital usage analytics, and qualitative approaches like interviews or focus groups—to provide a more comprehensive and balanced understanding of teachers’ actual competencies and perceptions.

Third, the absence of geolocation data limits the study’s ability to explore regional disparities in AI literacy across Saudi Arabia’s diverse educational environments. Teachers working in metropolitan areas may have different levels of access to AI tools and training compared to those in suburban or remote regions. Future research should collect and analyze geolocation data to assess how geographical factors influence AI integration and inform location-specific policy and training efforts.

Fourth, the demographic profile of the sample showed some homogeneity, with 77.5% of participants identifying as female and most being mid-career professionals. While this may reflect workforce trends in the local educational context, it restricts the generalizability of the findings across different teacher populations. Future studies should aim for more demographically diverse samples and explore how variables such as gender, age, and teaching experience influence AI literacy through subgroup analysis or moderation modeling.

Lastly, while the study aligns with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 in promoting technological readiness in education, it did not explore practical implementation strategies. Future research should engage in collaborative efforts with schools to co-design and test AI-integrated curricula, helping to bridge the gap between national policy objectives and classroom practice. Such partnerships would support more grounded, scalable, and contextually relevant applications of AI in K–12 education.

7. Conclusions

This study examined Saudi K–12 teachers’ AI literacy competence by examining four key constructs: awareness, ethics, evaluation, and use. The results indicate that teachers generally possess strong awareness and ethical understanding of AI technologies, though slightly less confidence in practical use and evaluation. SEM revealed that these competencies are significantly interrelated, with awareness serving as a foundational influence on ethical reasoning, evaluative skills, and eventual classroom application. Ethics, in turn, played a key role in enhancing both critical evaluation and practical use. Evaluation also emerged as a meaningful predictor of use, reinforcing reflective thinking’s importance in effective technology integration.

Together, these findings suggest that empowering teachers with AI literacy is not only about increasing their exposure to AI tools but also about cultivating a rich blend of conceptual understanding, ethical sensitivity, and practical confidence. As Saudi Arabia continues to invest in educational transformation under Vision 2030, these insights provide timely guidance for designing professional development, teacher preparation, and policy frameworks that support responsible, informed, and impactful AI integration in classrooms. Future studies should continue to build on this work by examining AI training’s longitudinal impacts, as well as AI literacy development across different educational contexts and grade levels.

Funding

The Authors acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University for its financial support under the grant number: KFU252313.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Research Ethics Committee at King Faisal University, KFU-REC-2023-AUG-ETHICS1031, issued on 23 August 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Survey instrument.

Table A1.

Survey instrument.

| Construct | Item |

|---|---|

| Awareness |

|

| |

| |

| Usage |

|

| |

| |

| Evaluation |

|

| |

| |

| Ethics |

|

| |

|

References

- Casal-Otero, L.; Catala, A.; Fernández-Morante, C.; Taboada, M.; Cebreiro, B.; Barro, S. AI literacy in K-12: A systematic literature review. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2023, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.T.K.; Su, J.; Leung, J.K.L.; Chu, S.K.W. Artificial intelligence (AI) literacy education in secondary schools: A review. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 23, 6204–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Magerko, B. What is AI literacy? Competencies and design considerations. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; Association for Computing Machinery (ACM): New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K.; Ahmad, Z.; Ismailov, M.; Sanusi, I.T. What are artificial intelligence literacy and competency? A comprehensive framework to support them. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, B.; Lu, J.; Jing, X. Empowering preservice teachers’ AI literacy: Current understanding, influential factors and strategies for improvement. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.T.K.; Leung, J.K.L.; Su, M.J.; Yim, I.H.Y.; Qiao, M.S.; Chu, S.K.W. AI Literacy in K-16 Classrooms; Springer International Publishing AG: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tenberga, I.; Daniela, L. Artificial intelligence literacy competencies for teachers through self-assessment tools. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.W. Fostering AI literacy: Overcoming concerns and nurturing confidence among preservice teachers. Inform. Learn. Sci. 2024, 126, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velander, J.; Taiye, M.A.; Otero, N.; Milrad, M. Artificial intelligence in K-12 education: Eliciting and reflecting on Swedish teachers’ understanding of AI and its implications for teaching & learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 4085–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Vision 2030. Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority. National Strategy for Data and AI (NSDAI). Available online: https://sdaia.gov.sa/en/SDAIA/SdaiaStrategies/Pages/NationalStrategyForDataAndAI.aspx (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Al-Abdullatif, A.M. Modeling teachers’ acceptance of generative artificial intelligence use in higher education: The role of AI literacy, intelligent TPACK and perceived trust. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdullatif, A.M.; Alsubaie, M.A. ChatGPT in learning: Assessing students’ use intentions through the lens of perceived value and the influence of AI literacy. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laupichler, M.C.; Aster, A.; Schirch, J.; Raupach, T. Artificial intelligence literacy in higher and adult education: A scoping literature review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Porayska-Pomsta, K. The Ethics of AI in Education: Practices, Challenges and Debates, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, A.C.E.; Shi, L.; Yang, H.; Choi, I. Enhancing teacher AI literacy and integration through different types of cases in teacher professional development. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Xue, Z.; Thai, K.-P. Performance comparison of an AI-based adaptive learning system in China. In Proceedings of the 2018 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Xi’an, China, 30 November–2 December 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 3170–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Loh, L.; Ng, E.; Chen, Y.; Wood, K.L.; Lim, K.H. Self-evolving adaptive learning for personalized education. In Proceedings of the CSCW ‘20 Companion: Companion Publication of the 2020 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Virtual, 17–21 October 2020; Association for Computing Machinery (ACM): New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhanna, M.A. Teachers’ perspectives of integrating AI-powered technologies in K-12 education for creating customized learning materials and resources. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 30, 10343–10371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Jones, M.V.; Burke, D. Affordances and challenges of artificial intelligence in K-12 education: A systematic review. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2024, 56, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K. Reform, challenges and future research on AI for K-12 education. In Empowering K-12 Education with AI; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.T.K.; Leung, J.K.L.; Chu, K.W.S.; Qiao, M.S. AI literacy: Definition, teaching, evaluation and ethical issues. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, A.; Okada, H.; Muto, Y. Contextualizing AI education for K-12 students to enhance their learning of AI literacy through culturally responsive approaches. Künstl. Intel. 2021, 35, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, W.; Tuomi, I. State of the art and practice in AI in education. Eur. J. Educ. 2022, 57, 542–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K.; Sanusi, I.T. Define, foster and assess student and teacher AI literacy and competency for all: Current status and future research direction. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 7, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wu, X.; Luo, H. Developing AI literacy for primary and middle school teachers in China: Based on a structural equation modeling analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, K.; Stenberg, C.J.; McGrath, C.; Åkerfeldt, A.; Heintz, F.; Stenliden, L. In search of artificial intelligence (AI) literacy in teacher education: A scoping review. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, I.H.Y.; Su, J. Artificial intelligence (AI) learning tools in K-12 education: A scoping review. J. Comput. Educ. 2024, 12, 93–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artificial Intelligence for K-12 Initiative. AI4K12. Available online: https://ai4k12.org (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- National Science Foundation. NSF Launches EducateAI Initiative. National Science Foundation News Release. 2023. Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/news/nsf-launches-educateai-initiative (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Kim, K.; Kwon, K. Exploring the AI competencies of elementary school teachers in South Korea. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 4, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.C.; Cheung, M.Y.W.; Tsang, O. Developing an artificial intelligence literacy framework: Evaluation of a literacy course for senior secondary students using a project-based learning approach. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amri, N.A.; Al-Abdullatif, A.M. Drivers of chatbot adoption among K–12 teachers in Saudi Arabia. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, N.S.; Alshehri, A.H. Prospects and obstacles in using artificial intelligence in Saudi Arabia higher education institutions—The potential of AI-based learning outcomes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Rau, P.L.P.; Yuan, T. Measuring user competence in using artificial intelligence: Validity and reliability of artificial intelligence literacy scale. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2023, 42, 1324–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneyli, A.; Burgul, N.S.; Dericioğlu, S.; Cenkova, N.; Becan, S.; Şimşek, Ş.E.; Güneralp, H. Exploring teacher awareness of artificial intelligence in education: A case study from Northern Cyprus. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2358–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, A.; Prather, J.; Edwards, J. Generative AI in education: A study of educators’ awareness, sentiments, and influencing factors. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Washington, DC, USA, 13–16 October 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.I. School teachers’ awareness and perceptions of artificial intelligence in science education: A study of secondary school. Synergy Int. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2024, 1, 24–29. Available online: https://sijmds.com/index.php/pub/article/view/9 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Alammari, A. Evaluating generative AI integration in Saudi Arabian education: A mixed-methods study. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. AI and Education: Guidance for Policymakers; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.; Kim, S.; Jang, Y.; Choi, S.; Kim, H. Developing an AI literacy diagnostic tool for elementary school students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 30, 1013–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS–SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeong, Y.; Ryu, J. Challenges and future directions of training program for AI literacy of K-12 teachers in Korea. In Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25 March 2024; Cohen, J., Solano, G., Eds.; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE): Waynesville, NC, USA, 2024; pp. 2432–2436. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/224317/ (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- UNESCO. AI Competency Framework for Teachers; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).