Unveiling Governance Mechanisms: How Board Characteristics Disclosure Moderates the Gender Diversity and Corporate Performance Nexus in Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Previous Studies Related to the Moderation and/or Mediator Impact on Gender Diversity and Corporate Performance Connection

2.2. Hypotheses

2.3. Data and Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Corporate Governance Characteristics Disclosure Index Impact on Financial Performance

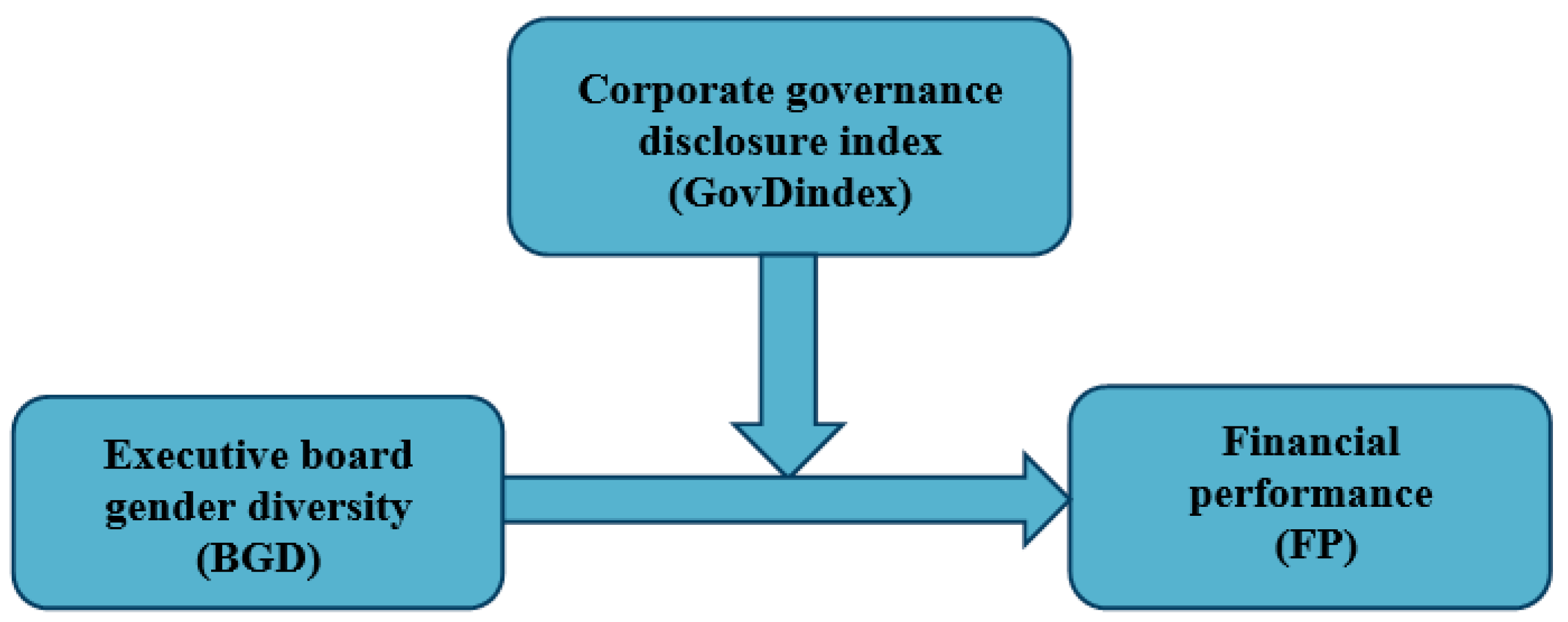

3.2. Corporate Governance Disclosure Index as a Moderator Between Executive Board Gender Diversity and Financial Performance

4. Robustness

4.1. Endogeneity Testing of the Moderating Role of Corporate Governance Disclosure Index, Using Two-Stage Least Square (2SLS) Estimation

4.2. Endogeneity Testing of the Moderating Role of Corporate Governance Disclosure Index on Executive Board Gender Diversity and Business Performance Using GMM Estimation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bilimoria, D.; Huse, M. A Qualitative Comparison of the Boardroom Experiences of U.S. and Norwegian Corporate Directors. Int. Rev. Women Leadersh. 1997, 3, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, C.M.; Certo, S.T.; Dalton, D.R. A Decade of Corporate Women: Some Progress in the Boardroom, None in the Executive Suite. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.B.; Ferreira, D. Gender Diversity in the Board Room. In ECGI Working Paper Series in Finance 57; European Corporate Governance Institute: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.A.; Simkins, B.J.; Simpson, W.G. Corporate Governance, Board Diversity, and Firm Value. Financ. Rev. 2003, 38, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Johannesen-Schmidt, M.C.; van Engen, M.L. Transformational, Transactional, and Laissez-Faire Leadership Styles: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Women and Men. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 569–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barron, L.G.; Hebl, M. The Force of Law: The Effects of Sexual Orientation Antidiscrimination Legislation on Interpersonal Discrimination in Employment. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2013, 19, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Terjesen, S.; Vinnicombe, S. Newly Appointed Directors in the Boardroom: How Do Women and Men Differ? Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, L.N.; Gherghina, Ş.C.; Tawil, H.; Sheikha, Z. Does Board Gender Diversity Affect Firm Performance? Empirical Evidence from Standard & Poor’s 500 Information Technology Sector. Financ. Innov. 2021, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, I. Board Gender Diversity and Sustainability Performance: Nordic Evidence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1495–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soare, T.-M.; Detilleux, C.; Deschacht, N. The Impact of the Gender Composition of Company Boards on Firm Performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2021, 71, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluchna, M.; Honig, B.; Kamiński, B. Glass Ceiling or Glass Cliff: An Examination of the Role of Female Board Members on Market Performance in Poland. Post-Communist Econ. 2023, 35, 926–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gipson, A.N.; Pfaff, D.L.; Mendelsohn, D.B.; Catenacci, L.T.; Burke, W.W. Women and Leadership: Selection, Development, Leadership Style, and Performance. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2017, 53, 32–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, U.U.; Iqbal, A. Nexus of Knowledge-Oriented Leadership, Knowledge Management, Innovation and Organizational Performance in Higher Education. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2020, 26, 1731–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Hou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y. The Relationship between Female Leadership Traits and Employee Innovation Performance—The Mediating Role of Knowledge Sharing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari Abdullah, S.; Rehman, A.U.; Abdullah Alreshoodi, S.; Abdul Rab, M. How Entrepreneurial Competencies Influence the Leadership Style: A Study of Saudi Female Entrepreneurs. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2202025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Meca, E.; García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Board Diversity and Its Effects on Bank Performance: An International Analysis. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 53, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melón-Izco, Á.; Ruiz-Cabestre, F.J.; Ruiz-Olalla, M.C. Diversity in the Board of Directors and Good Governance Practices. Econ. Bus. Lett. 2020, 9, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N.; Baydauletov, M. Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy and Corporate Environmental and Social Performance: The Moderating Role of Board Gender Diversity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1664–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls Martínez, M.d.C.; Santos-Jaén, J.M.; Soriano Román, R.; Martín-Cervantes, P.A. Are Gender and Cultural Diversities on Board Related to Corporate CO2 Emissions? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIGE. Gender Equality Index 2024: Sustaining Momentum on a Fragile Path; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024.

- Robayo-Abril, M.; Chilera, C.P.; Rude, B.; Costache, I. Gender Equality in Romania: Where Do We Stand?—Romania Gender Assessment; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/40666 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- PwC. Gender Pay Gap Report; PwC Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2024; Available online: https://hrleadersportal.pwc.com/media/1408/pwc-romania-gender-pay-gap-report-2024.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Deloitte; PWNR. Women on Boards in Romania; Deloitte Romania & Professional Women’s Network Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2022; Available online: https://www.amcham.ro/business-intelligence/deloitte-pwnr-report-romania-reports-progress-in-leadership-gender-balance.-62-of-the-companies-listed-on-the-bucharest-stock-exchange-have-women-on-boards-and-65-of-them-in-the-executive-committees (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Noja, G.G.; Thalassinos, E.; Cristea, M.; Grecu, I.M. The Interplay between Board Characteristics, Financial Performance, and Risk Management Disclosure in the Financial Services Sector: New Empirical Evidence from Europe. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marashdeh, Z.; Alomari, M.W.; Aleqab, M.M.; Alqatamin, R.M. Board Characteristics and Firm Performance: The Case of Jordanian Non-Financial Institutions. J. Gov. Regul. 2021, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amosh, H.; Khatib, S.F.A. Corporate Governance and Voluntary Disclosure of Sustainability Performance: The Case of Jordan. SN Bus. Econ. 2021, 1, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Nguyen, D.M.; Le, T. The Effect of Corporate Governance Elements on Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting of Listed Companies in Vietnam. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2170522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamukama, N.; Kyomuhangi, D.S.; Akisimire, R.; Orobia, L.A. Competitive Advantage: Mediator of Managerial Competence and Financial Performance of Commercial Banks in Uganda. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2017, 8, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Frijat, Y.S.; Albawwat, I.E.; Elamer, A.A. Exploring the Mediating Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Connection between Board Competence and Corporate Financial Performance amidst Global Uncertainties. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 31, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, P.d.C.; Seles, B.M.R.P.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Mariano, E.B.; Jabbour, A.B.L. de S. Management Theory and Big Data Literature: From a Review to a Research Agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Rehman, R.U.; Ali, R.; Ntim, C.G. Does Gender Diversity on the Board Reduce Agency Cost? Evidence from Pakistan. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 37, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailani, D.; Hulu, M.Z.T.; Simamora, M.R.; Kesuma, S.A. Resource-Based View Theory to Achieve a Sustainable Competitive Advantage of the Firm: Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Entrep. Sustain. Stud. 2024, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Cannella, A.A.; Paetzold, R.L. The Resource Dependence Role of Corporate Directors: Strategic Adaptation of Board Composition in Response to Environmental Change. J. Manag. Stud. 2000, 37, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, J.-J.; Hayes, A.F. Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: Concepts, Computations, and Some Common Confusions. Span. J. Psychol. 2021, 24, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, C.; Rivera Ottenberger, D.; Moessner, M.; Crosby, R.D.; Ditzen, B. Depressed and Swiping My Problems for Later: The Moderation Effect between Procrastination and Depressive Symptomatology on Internet Addiction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4625-4903-0. [Google Scholar]

- Holbert, R.L.; Park, E. Conceptualizing, Organizing, and Positing Moderation in Communication Research. Commun. Theory 2020, 30, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, R. Exploring the Linkages between Firm Misconduct and Entrepreneurial Growth in China. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2023, 30, 1503–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karajeh, A.I. The Moderating Role of Board Diversity in the Nexus between the Quality of Financial Disclosure and Dividends in Jordanian-Listed Banks. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2022, 15, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xu, C.; Wan, G. Exploring the Impact of TMTs’ Overseas Experiences on Innovation Performance of Chinese Enterprises: The Mediating Effects of R&D Strategic Decision-Making. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2019, 13, 1044–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezső, C.L.; Ross, D.G. Does Female Representation in Top Management Improve Firm Performance? A Panel Data Investigation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y. Women on Boards and Bank Earnings Management: From Zero to Hero. J. Bank. Financ. 2019, 107, 105607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Yoon, Y.N.; Kang, K.H. The Relationship between Board Diversity and Firm Performance in the Lodging Industry: The Moderating Role of Internationalization. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaifi, H.A.; Al-Qadasi, A.A.; Al-Rassas, A.H. Board Diversity Effects on Environmental Performance and the Moderating Effect of Board Independence: Evidence from the Asia-Pacific Region. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2210349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Cardenas, V.; Gonzalez-Ruiz, J.D.; Duque-Grisales, E. Board Gender Diversity and Firm Performance: Evidence from Latin America. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2022, 12, 785–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Husnain, M.; Ullah, S.; Khan, M.T.; Ali, W. Gender Diversity and Firms’ Sustainable Performance: Moderating Role of CEO Duality in Emerging Equity Market. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alodat, A.Y.; Salleh, Z.; Nobanee, H.; Hashim, H.A. Board Gender Diversity and Firm Performance: The Mediating Role of Sustainability Disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2053–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.G.M.; Ivascu, L. Accentuating the Moderating Influence of Green Innovation, Environmental Disclosure, Environmental Performance, and Innovation Output between Vigorous Board and Romanian Manufacturing Firms’ Performance. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 10569–10589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.H. Environmental, Social and Governance Performance and Financial Risk: Moderating Role of ESG Controversies and Board Gender Diversity. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitar, K.; Hussainey, K.; Kolade, N.; Gerged, A.M. ESG Disclosure and Firm Performance before and after IR: The Moderating Role of Governance Mechanisms. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2020, 28, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, U.-E.-R.; Jalal, R.N.-U.-D.; Venditti, M.; Minguez-Vera, A. Diverse Boards and Firm Performance: The Role of Environmental, Social and Governance Disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1457–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahloul, I.; Sbai, H.; Grira, J. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting Improve Financial Performance? The Moderating Role of Board Diversity and Gender Composition. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 84, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, H.B.; Chouaibi, J. Gender Diversity, Financial Performance, and the Moderating Effect of CSR: Empirical Evidence from UK Financial Institutions. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2023, 23, 1506–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. Is Board Gender Diversity Linked to Financial Performance? The Mediating Mechanism of CSR. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57, 863–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsni, S.; Otchere, I.; Shahriar, S. Board Gender Diversity, Firm Performance and Risk-Taking in Developing Countries: The Moderating Effect of Culture. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2021, 73, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lee, E.; Lyu, C.; Zhu, Z. The Effect of Accounting Academics in the Boardroom on the Value Relevance of Financial Reporting Information. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2016, 45, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, B.; Hasan, I.; Wu, Q. Professors in the Boardroom and Their Impact on Corporate Governance and Firm Performance. Financ. Manag. 2015, 44, 547–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampouris, I.; Mertzanis, C.; Samitas, A. Foreign Ownership and the Financing Constraints of Firms Operating in a Multinational Environment. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso-Castro, C.; Pérez-Calero, L.; Vecino-Gravel, J.D.; Villegas-Periñán, M.d.M. The Challenge of Board Composition: Effects of Board Resource Variety and Faultlines on the Degree of a Firm’s International Activity. Long Range Plan. 2022, 55, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.-O. Do Corporate Board Compensation Characteristics Influence the Financial Performance of Listed Companies? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, M.A.; Velásquez, J.S.; Ortúzar, S. Gender and Decision-Making Styles in Male and Female Managers of Chilean SMEs. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2023, 36, 289–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.P.; Nguyen, B.H. The Impact of Board Size, Ownership Structure and Characteristics of the Supervisory Board on the Financial Performance of Listed Companies in Vietnam. Tech. Bus. Manag. 2024, 8, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.-O.; Ienciu, I.; Bonaci, C.; Filip, C. Board Characteristics Best Practices and Financial Performance. Evidence from the European Capital Market. Amfiteatru Econ. 2014, 16, 672–683. [Google Scholar]

- Suciu, M.-C.; Noja, G.G.; Cristea, M. Diversity, Social Inclusion and Human Capital Development as Fundamentals of Financial Performance and Risk Mitigation. Amfiteatru Econ. 2020, 22, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, P.; Roth, L. Learning from Directors’ Foreign Board Experiences. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 51, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Ding, K.; Park, H. Cross-Listing, Foreign Independent Directors and Firm Value. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Guo, R.; Ning, L. Intangible Assets and Foreign Ownership in International Joint Ventures: The Moderating Role of Related and Unrelated Industrial Agglomeration. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022, 61, 101654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.W. Institutional Unpredictability and Foreign Exit−reentry Dynamics: The Moderating Role of Foreign Ownership. J. World Bus. 2023, 58, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.L.; Vo, T.T.A.; Vo, X.V.; Thi My Nguyen, L. Does Foreign Institutional Ownership Matter for Stock Price Synchronicity? International Evidence. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2023, 67, 100783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, N.; NIcolò, G.; Polcini, P.T.; Vitolla, F. Corporate Governance and Risk Disclosure: Evidence from Integrated Reporting Adopters. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2022, 22, 1462–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxumalo, L.; Dlungwane, S.; Nomlala, B.C. The Relationship between Corporate Governance and Firm Profitability among JSE-Listed Basic Materials Sector Firms. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Kim, S.-I. Female Executives and Firm Value: The Moderating Effect of Co-CEO Power Gaps. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 37, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, F.E.; Tenuta, P.; Cambrea, D.R. Five Shades of Women: Evidence from Italian Listed Firms. Meditari Account. Res. 2021, 29, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, M.N.; Bernardi, R.A.; Bosco, S.M.; Landry, E.E. Does the Presence of Three or More Female Directors Associate with Corporate Recognition? Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 38, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, J.; Miladi, E.; Elouni, N. Exploring the Relationship between Board Characteristics and Environmental Disclosure: Empirical Evidence for European Firms. J. Account. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2022, 21, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, D.A.R.M.; Hasan, A.; Obioru, B.; Nakpodia, F. Corporate Governance and Environmental Disclosure: A Comparative Analysis. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2024, 24, 210–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suherman, S.; Mahfirah, T.F.; Usman, B.; Kurniawati, H.; Kurnianti, D. CEO Characteristics and Firm Performance: Evidence from a Southeast Asian Country. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2023, 23, 1526–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.C.; Nguyen, C.V. Does the Education Level of the CEO and CFO Affect the Profitability of Real Estate and Construction Companies? Evidence from Vietnam. Heliyon 2024, 10, E28376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavertiaeva, M.; Shenkman, E.; Kazarina, E. Does Independence of Board Committees Enhance Corporate Performance? The Case of Russia. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2023, 60, 1316–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.U.; Zahid, M.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Does Firm Better Financial Performance Amplify the Role of Women Directors and Their Certain Characteristics in Promoting Corporate Sustainability Practices? Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Méndez, C.; Correa, A.I. Gender and Financial Performance in SMEs in Emerging Economies. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 37, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.U.; Zahid, M. Women Directors and Corporate Performance: Firm Size and Board Monitoring as the Least Focused Factors. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 36, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does It Pay to Be Good … And Does It Matter? A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Corporate Social and Financial Performance. SSRN Electron. J. 2009, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahma, S.; Nwafor, C.; Boateng, A. Board Gender Diversity and Firm Performance: The UK Evidence. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 26, 5704–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Deng, X.; Álvarez-Otero, S.; Sial, M.S.; Comite, U.; Cherian, J.; Oláh, J. Impact of Women and Independent Directors on Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance: Empirical Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A. Gender Diversity in Boardroom and Its Impact on Firm Performance. J. Manag. Gov. 2022, 26, 735–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, V.; Popa, D.-N.; Beleneşi, M. The Complexity of Interaction between Executive Board Gender Diversity and Financial Performance: A Panel Analysis Approach Based on Random Effects. Complexity 2022, 2022, 9559342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheja, C.G. Determinants of Board Size and Composition: A Theory of Corporate Boards. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2005, 40, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.B.; Ferreira, D. Women in the Boardroom and Their Impact on Governance and Performance. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 94, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintoki, M.B.; Linck, J.S.; Netter, J.M. Endogeneity and the Dynamics of Internal Corporate Governance. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 105, 581–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Akhtar, P.; Zaefarian, G. Dealing with Endogeneity Bias: The Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) for Panel Data. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 71, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.A.B.C.; Castro, F.H.; Silveira, A.D.M.d.; Bergmann, D.R. Endogeneity in Panel Data Regressions: Methodological Guidance for Corporate Finance Researchers. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2020, 22, 437–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, S. Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects. Econometrica 1981, 49, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Lin, K.Z.; Wong, W. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting and Firm Performance: Evidence from China. J. Manag. Gov. 2016, 20, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, L.-Y.; Leung, A.S.M. Corporate Social Responsibility, Firm Reputation, and Firm Performance: The Role of Ethical Leadership. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 31, 925–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B.H. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data; Springer Texts in Business and Economics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-53952-8. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S.; Windmeijer, F. Estimation in Dynamic Panel Data Models: Improving on the Performance of the Standard GMM Estimator. In Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2001; Volume 15, pp. 53–91. ISBN 978-0-7623-0688-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sial, M.S.; Chunmei, Z.; Khan, T.; Nguyen, V.K. Corporate Social Responsibility, Firm Performance and the Moderating Effect of Earnings Management in Chinese Firms. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2018, 10, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Cherian, J.; Sial, M.S.; Wan, P.; Filipe, J.A.; Mata, M.N.; Chen, X. The Moderating Role of CSR in Board Gender Diversity and Firm Financial Performance: Empirical Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2021, 34, 2354–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yang, J.; Gao, Z. Do Female Board Directors Promote Corporate Social Responsibility? An Empirical Study Based on the Critical Mass Theory. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2019, 55, 3452–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chijoke-Mgbame, A.M.; Boateng, A.; Mgbame, C.O. Board Gender Diversity, Audit Committee and Financial Performance: Evidence from Nigeria. Account. Forum 2020, 44, 262–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robustness tests: Alternative metrics for business financial performance | |||||

| Independent variables | Composite index | ROE | ROA | EPS | SOL |

| Disclosure index | 13.90 *** | 0.157 * | 0.033 ** | 0.99 | 11.77 *** |

| Board size | 1.00 *** | 0.0089 *** | 0.0035 *** | 0.87 *** | 0.266 |

| Big4 | 3.23 | 0.092 | 0.021 ** | 1.83 ** | −0.005 |

| Governance reports detailed inf. | −3.32 | −0.27 ** | −0.016 | −0.53 | −1.58 |

| Constant | 41.03 *** | −0.089 | −0.0065 | −4.75 ** | 1.649 |

| Observations | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 |

| F-test | 3.75 *** | 3.06 *** | 3.08 *** | 9.01 *** | 5.63 *** |

| S.E. of Reg. | 19.66 | 0.0158 | 0.097 | 12.50 | 11.59 |

| R2 | 28.68 | 23.54 | 23.74 | 66.28 | 34.9 |

| Jarque–Bera test | 28.32 (0.00) | 61.02 (0.00) | 13.49 (0.00) | 36.14 (0.00) | 41.97 (0.00) |

| Random effects–Lagrange Multiplier test | 448.54 (0.00) | 40.13 (0.00) | 81.43 (0.00) | 10.41 (0.00) | 158.06 (0.00) |

| Hausman test prob. | 0.49 | 0.6752 | 0.8189 | 0.432 | 0.2345 |

| Residual Cross-Section Dependence Test | |||||

| Breusch–Pagan LM test | 2925 (0.00) | 2874.72 (0.00) | 2504.1 (0.00) | 3230.55 (0.00) | 3103.18 (0.00) |

| Pesaran Scaled LM test | 23.53 (0.00) | 22.63 (0.00) | 16.07 (0.00) | 28.93 (0.00) | 26.67 (0.00) |

| Pesaran CD test | −0.71 (0.47) | −0.59 (0.55) | 0.45 (0.64) | −0.52 (0.00) | −0.196 (0.84) |

| Panel Cross-Section Heteroskedasticity LR test | 149.80 (0.00) | 2421.68 (0.00) | 988.45 (0.00) | 4678.93 (0.00) | 2151.15 (0.00) |

| Models | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | M11 | M12 | M13 | M14 | M15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robustness tests | ||||||||||

| Independent variables | Composite index | Comp_index | ROE | ROA | EPS | SOL | ROE | ROA | EPS | SOL |

| Proportion of females Mn | 13.96 ** | 0.251 * | 0.048 * | 3.755 | 6.63 *** | |||||

| Blau index | 14.81 * | 0.218 | 0.06 * | 5.26 | −1.278 | |||||

| Disclosure index | 18.26 *** | 21.68 *** | 0.235 ** | 0.047 *** | 3.68 | 8.79 ** | 0.213 * | 0.05 ** | 4.69 | 16.59 ** |

| Proportion of female Mn*Dindex | −20.10 * | −0.29 * | −0.053 * | −9.97 * | −58.23 ** | |||||

| D index*Blau index | −35.88 ** | −2.54 | −0.088 | −15.75 ** | −29.34 ** | |||||

| Board size | 1.00 *** | 0.87 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.035 *** | 0.89 *** | 0.88 ** | 0.007 * | 0.003 *** | 0.88 *** | 0.83 * |

| Big4 | 3.37 | 3.66 | 0.09 * | 0.02 | 1.76 ** | 3.38 ** | 0.094 | 0.022 ** | 2.01 ** | 3.01 * |

| Gov reports | −3.23 | −2.72 | −0.27 * | −0.016 | −0.45 | −1.70 | −0.269 ** | −0.016 | −0.278 | −1.57 |

| Const, | 37.52 *** | 38.22 *** | −0.153 * | −0.018 | −5.89 | −3.93 *** | −0.018 | −6.16 *** | −5.13 | |

| Obs | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 |

| F-test | 3.34 *** | 3.29 ** | 2.34 ** | 2.56 ** | 6.77 *** | 2.176 *** | 2.14 ** | 2.48 *** | 7.14 *** | 5.48 *** |

| S.E. of Reg. | 19.74 | 19.61 | 0.69 | 0.097 | 12.55 | 10.59 | 0.69 | 0.096 | 12.56 | 11.22 |

| R2 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.248 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

| Jarque–Bera | 28.56 (0.00) | 25.93 (0.00) | 63.00 (0.00) | 13.33 (0.00) | 35.98 (0.00) | 30.72 (0.00) | 61.34 (0.00) | 13.21 (0.00) | 36.05 (0.00) | 43.13 (0.00) |

| Random effects–Lagrange Multiplier T | 371.30 (0.000) | 423.11 (0.00) | 35.37 (0.00) | 74.31 (0.00) | 6.99 (0.00) | 169.19 (0.00) | 38.66 (0.00) | 83.18 (0.00) | 6.07 (0.00) | 147.48 (0.00) |

| Hausman T prob. | 0.198 | 0.1743 | 0.6686 | 0.7783 | 0.2831 | 0.2831 | 0.8381 | 0.4613 | 0.189 | 0.178 |

| Residual Cross-Section Dependence Test prob. | ||||||||||

| Breusch–Pagan LM | 2935.80 (0.00) | 2877.62 (0.00) | 2894.05 (0.00) | 2658.09 (0.00) | 3085.59 (0.00) | 3779.01 (0.00) | 2870.55 (0.00) | 2562.08 (0.00) | 3636.44 (0.00) | 3244.16 (0.00) |

| Pesaran Scaled LM | 23.71 (0.00) | 22.68 (0.00) | 22.97 (0.00) | 18.79 (0.00) | 26.36 (0.00) | 38.63 (0.00) | 22.55 (0.00) | 17.09 (0.00) | 36.11 (0.00) | 29.17 (0.00) |

| Pesaran CD | −0.60 (0.54) | −0.44 (065) | −0.90 (0.36) | 0.08 (0.93) | −0.19 (0.84) | −0.50 (0.61) | −0.92 (035) | 0.125 (0.89) | 0.43 (0.66) | −0.32 (0.74) |

| Panel Cross-Section Heteros. LR T prob. | 139.46 (0.00) | 148.88 (0.00) | 2420.51 (0.00) | 988.90 (0.00) | 4685.47 (0.00) | 2138.62 (0.00) | 2429.62 (0.00) | 991.28 (0.00) | 4686.78 (0.00) | 2169.71 (0.00) |

| Models | M6’ | M7’ | M8’ | M9’ | M10’ | M11’ | M12’ | M13’ | M14’ | M15’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endogeneity problem (2SLS) | ||||||||||

| Independent variables | Comp _index | Comp_index | ROE | ROA | EPS | SOL | ROE | ROA | EPS | SOL |

| Proportion of women executives | 14.09 *** | 0.248 * | 0.048 | 3.78 | −1.31 | |||||

| Blau index | 14.85 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 5.29 | 2.75 | |||||

| Disclosure index | 17.92 *** | 21.38 *** | 0.217 ** | 0.046 *** | 3.72 | 0.966 | 02.14 ** | 0.052 ** | 4.74 | 8.28 |

| Proportion of female manager*Dinex | −20.51 ** | −0.332 * | −0.055 * | −10.17 * | −44.87 ** | |||||

| Blau index* Dindex | −36.55 ** | −0.38 | −0.09 * | −16.01 * | 15.24 | |||||

| Board size | 1.03 *** | 0.89 ** | 0.01 *** | 0.0036 *** | 0.90 *** | 0.242 | 0.009 ** | 0.0033 | 0.886 *** | 0.224 |

| Big4 | 3.17 | 3.46 | 0.069 | 0.019 | 1.72 ** | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 1.99 ** | −0.22 |

| Constant | 36.70 *** | 37.43 *** | −0.22 * | −0.023 | −6.03 * | 1.65 | −0.20 * | −0.02 | −6.25 ** | 0.92 |

| R2 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.45 | 0.05 |

| Models | M16 | M17 | M18 | M19 | M20 | M21 | M22 | M23 | M24 | M25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endogeneity problem with GMM estimator | ||||||||||

| Independent variables | Comp index | Comp_index | ROE | ROA | EPS | SOL | ROE | ROA | EPS | SOL |

| Lagged Dep. variable | 0.369 *** | 0.363 *** | 0.047 *** | 0.036 ** | −0.119 | 0.332 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.031 *** | −0.12 *** | 0.324 *** |

| Proportion of female managers | 13.649 ** | 0.616 *** | 0.116 *** | 0.636 | 16.93 ** | |||||

| Blau index | 15.00 * | 0.172 *** | 0.115 *** | 4.36 *** | −1.27 | |||||

| Disclosure index | 4.98 | 9.52 * | 0.369 *** | 0.067 *** | −2.42 | 1.6882 | 0.205 *** | 0.094 *** | 2.805 *** | 4.78 * |

| Proportion of female managers*D index | −25.72 ** | −1.021 *** | −0.167 *** | −0.807 | −51.59 *** | |||||

| Blau index* Dindex | −60.48 *** | −0.398 *** | −0.26 *** | −21.17 *** | −29.38 *** | |||||

| Board size | 0.389 | 0.44 | −0.05 ** | −0.0050 | 1.67 *** | 1.83 *** | −0.043 *** | −0.007 * | 1.67 *** | 1.53 *** |

| Big4 | 9.99 | 11.89 * | 0.392 *** | 0.052 *** | 11.99 *** | 2.80 ** | 0.41 *** | 0.069 *** | 11.85 *** | 3.63 ** |

| Firm size | 0.099 | −0.28 | 0.015 ** | 0.012 | −1.28 *** | −10.43 *** | 0.016 **** | 0.018 *** | −1.197 *** | −12.34 *** |

| Leverage | 1.169 *** | 1.08 *** | 0.138 *** | 0.0044 *** | 0.26 *** | −0.128 | 0.137 *** | 0.0039 *** | 0.261 *** | 0.196 |

| Year dummies | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Industry dummies | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Sargan J-stat | 25.36 | 24.58 | 36.55 | 30.13 | 55.51 | 27.07 | 44.53 | 29.09 | 54.42 | 29.21 |

| No. instrum. (groups) | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 |

| No. of observations | 389 | 389 | 389 | 389 | 389 | 389 | 389 | 389 | 389 | 389 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bogdan, V.; Popa, D.-N.; Matica, D.-E.; Beleneşi, M. Unveiling Governance Mechanisms: How Board Characteristics Disclosure Moderates the Gender Diversity and Corporate Performance Nexus in Romania. Systems 2025, 13, 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060420

Bogdan V, Popa D-N, Matica D-E, Beleneşi M. Unveiling Governance Mechanisms: How Board Characteristics Disclosure Moderates the Gender Diversity and Corporate Performance Nexus in Romania. Systems. 2025; 13(6):420. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060420

Chicago/Turabian StyleBogdan, Victoria, Dorina-Nicoleta Popa, Diana-Elisabeta Matica, and Mărioara Beleneşi. 2025. "Unveiling Governance Mechanisms: How Board Characteristics Disclosure Moderates the Gender Diversity and Corporate Performance Nexus in Romania" Systems 13, no. 6: 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060420

APA StyleBogdan, V., Popa, D.-N., Matica, D.-E., & Beleneşi, M. (2025). Unveiling Governance Mechanisms: How Board Characteristics Disclosure Moderates the Gender Diversity and Corporate Performance Nexus in Romania. Systems, 13(6), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060420