Abstract

Digital transformation has become a strategic imperative for micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in emerging economies, yet the mechanisms linking digitalization to performance outcomes remain underexplored. This study examines how the strategic emphasis on digital transformation and the breadth of technology adoption influence firm performance among MSEs in Bhutan. Drawing on an integrative theoretical framework combining diffusion of innovations theory, the resource-based view, and institutional theory, survey data from 217 MSEs were analyzed using regression and interaction modeling techniques. The findings indicate that firms with stronger digital strategic emphasis adopt a broader range of technologies and achieve superior performance. However, unstructured or excessive knowledge sharing negatively moderates these relationships, potentially creating cognitive overload and impeding digital strategy execution. Furthermore, tourism enterprises exhibit significantly higher levels of digital engagement compared to non-tourism counterparts, highlighting the role of sector-specific institutional pressures. By uncovering the systemic dynamics between strategic orientation, technology adoption, and knowledge flows, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how digital transformation processes can be optimized in resource-constrained environments. These findings not only offer practical insights for enhancing digital readiness and organizational resilience among small enterprises but also contribute to the broader theoretical discourse on how strategic orientation and contextual moderators shape the effectiveness of digital transformation in emerging markets.

1. Introduction

In today’s rapidly evolving business environment, digital transformation has emerged as a core strategic imperative, rather than a mere technological option, for ensuring organizational competitiveness, operational efficiency, and long-term sustainability [1]. The wave of digitalization is no longer limited to large multinational enterprises; micro and small enterprises (MSEs) are also adopting advanced technologies such as big data, artificial intelligence (AI), and blockchain to swiftly respond to shifting customer demands, integrate supply chains, and optimize internal operations [2,3,4,5,6]. Such strategic digitalization enhances overall performance by increasing operational efficiency, reducing costs, and improving agility [7,8], ultimately contributing to superior firm performance.

Despite these promising outcomes, not all organizations achieve the same level of success through digital transformation. This suggests that technological adoption alone is insufficient; the impact of digitalization is contingent upon internal organizational conditions [9,10]. In particular, how strategically digitalization is emphasized within an organization becomes a critical determinant of the breadth and effectiveness of digital implementation [11,12]. This study also responds to recent calls for more empirical research on how digital technology adoption influences SME performance [2].

As the strategic drivers of digital transformation have gained increased attention, internal management processes—especially the role of knowledge sharing—have also come into focus. Given the complex and integrated nature of digital technologies across organizations, effective responses require high-quality flows of knowledge, including the creation, dissemination, and application of relevant information [13,14]. Even if digital transformation is prioritized at the strategic level, it must be absorbed and implemented through a well-structured internal knowledge system [15,16].

Accordingly, the extant literature has identified knowledge sharing as a key mechanism for facilitating organizational learning, innovation, and the diffusion of digital transformation [17,18]. However, when knowledge flows are excessive or poorly coordinated, they may hinder decision quality and overwhelm internal systems, especially in highly digitalized organizations [19,20]. This risk becomes particularly salient in organizations dealing with complex and diverse digital technologies. Yet, existing studies have primarily focused on the positive aspects of knowledge sharing, leaving its potential moderating effects in digital transformation processes underexplored [21].

To explain the mechanisms underlying digital transformation in MSEs, this study adopts a three-dimensional theoretical framework encompassing strategic drivers, internal capabilities, and institutional conditions, each aligned with theories that address structural and contextual constraints common to emerging markets like Bhutan. Diffusion of innovations theory and organizational readiness for change explain how managerial intent and organizational preparedness influence the pace and breadth of digital adoption, particularly relevant in firms with low digital maturity [22,23]. The resource-based view and dynamic capabilities theory highlight how internal resources and reconfigurable capabilities enable firms to convert technology use into performance outcomes, which is critical when organizational capacity is limited [24,25]. Institutional theory complements these perspectives by explaining how sector-specific pressures, such as real-time customer demands in tourism or regulatory inertia in non-tourism sectors, may moderate strategic responses to digitalization [26,27]. Together, these theories provide a cohesive lens through which to analyze how digital strategies unfold under both organizational and environmental constraints.

In particular, industry context can serve as a crucial moderating variable in the relationship between digital transformation and firm performance. Digitalization does not occur in a uniform manner across all organizations, and its strategic significance and modes of execution differ depending on the institutional environment of the industry [28,29]. Nevertheless, the influence of such industry-specific institutional factors remains underexplored. This study, therefore, draws upon institutional theory to interpret the normative and coercive pressures exerted by industries on digital strategies. This suggests that sectoral differences in institutional demands may play a moderating role in the relationship between strategic emphasis on digitalization and the scope of digital technology adoption [30,31].

Although prior research has linked digital adoption to performance outcomes, little attention has been given to how strategic emphasis on digitalization interacts with internal knowledge sharing structures, particularly in the context of micro and small enterprises (MSEs), where limited resources often constrain implementation [21,25,32,33]. The role of institutional pressures across industries has also been largely overlooked as a potential moderating factor [34]. This study responds to these gaps by examining how digital strategies influence both the scope of technology adoption and firm performance, and how these relationships vary depending on knowledge practices and industry context [35,36].

Against this backdrop, the present study poses the following research questions: How does the strategic emphasis on digitalization affect the scope of technology adoption and firm performance in MSEs? Moreover, how are these relationships moderated by knowledge sharing and industry sector (tourism vs. non-tourism)? To answer these questions, this study adopts a multi-theoretical framework, incorporating the diffusion of innovations theory, organizational readiness for change theory, resource-based view, dynamic capabilities theory, information processing theory, and institutional theory.

For the empirical investigation, this study focuses on MSEs in Bhutan—an emerging economy where digital transformation is still in a nascent stage but is becoming increasingly crucial for business continuity and growth. Bhutan offers a relevant context for analyzing how digital emphasis and diffusion translate into organizational value, especially as digital infrastructure continues to expand and digital dependency increases in sectors like tourism [37,38,39]. In light of limited access to financial data among MSEs, a survey-based methodology was adopted for the analysis.

This study approaches digital transformation as a multifaceted organizational phenomenon shaped by the interplay of strategic intent, internal execution, and contextual forces. By examining how knowledge sharing and institutional environments condition the relationship between digital strategy and performance, the study offers practical insights for developing context-sensitive digital approaches tailored to micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in emerging markets. Furthermore, by applying a multi-theoretical framework to a setting that has been relatively under-represented in mainstream digitalization research, the study contributes empirical clarity and conceptual depth to ongoing discussions of how digital transformation unfolds in resource-constrained environments.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Firm Performance as an Outcome of Digital Transformation

One of the primary goals of digital transformation is the enhancement of firm performance. In this study, firm performance is conceptualized as a core outcome variable that reflects the effectiveness of strategic implementation. It encompasses not only financial indicators but also multidimensional aspects such as agility, innovation, and customer satisfaction [40,41,42,43]. Digital technologies act as instruments and mediators to achieve these performance outcomes.

Previous research has shown that firms that successfully adapt to digital transformation tend to experience improvements in operational efficiency, market responsiveness, and customer experience, ultimately achieving competitive advantage [8,13,44]. However, the adoption of technology alone does not guarantee expected outcomes. Digital transformation leads to performance gains only when it is strategically emphasized, supported by strong internal execution capabilities, and aligned with the external environment [5,6]. Accordingly, this study analyzes the mechanisms of digital transformation through three analytical dimensions: strategic drivers, internal implementation capabilities, and external institutional context.

2.2. Strategic Drivers: Emphasis on Digitalization

The extent to which organizations prioritize and emphasize digital transformation plays a crucial role in determining the speed, scope, and depth of technology adoption and execution. Strategic drivers reflect not only declarative commitments but also tangible behaviors, including leadership intent, employee awareness, and resource allocation [10,45,46].

According to diffusion theory, the more organizations strategically emphasize digitalization, the more they foster an innovation-friendly environment, thereby accelerating the pace and expanding the breadth of technology diffusion [12,47]. Such emphasis is often shaped by early adopters’ attitudes and top management leadership, which help embed a digital culture across the organization [9].

Organizational readiness for change theory further suggests that employees’ psychological and behavioral readiness is a critical determinant of successful transformation [48]. Similarly, the Technology Readiness Index (TRI) emphasizes the importance of organizations’ capacity and willingness to embrace new technologies [11,49]. Firms that strategically stress digitalization tend to boost their members’ readiness, reduce resistance to change, and strengthen the foundation for implementation [50].

This strategic emphasis, therefore, is not merely rhetorical but functions as a departure point of the digital performance mechanism by influencing the subsequent implementation capabilities and ultimately firm performance [25].

2.3. Internal Implementation Capabilities: Range of Digitalization

While strategic emphasis provides direction, realizing performance outcomes requires execution capabilities. The range of digitalization reflects how broadly and deeply digital technologies are integrated into organizational functions, assessing whether technology adoption has become a part of operational processes [51,52].

From a resource-based view, competitive advantage stems from rare and inimitable internal resources. Rather than technology per se, it is the embedded capabilities—such as IT infrastructure, data analytics, and human capital—that significantly influence performance [33,53,54]. Therefore, the alignment between digital technology and existing resources is crucial.

Dynamic capabilities theory highlights the importance of integrating, coordinating, and reconfiguring resources to adapt to turbulent environments. In this context, the range of digitalization represents a tangible outcome of dynamic capabilities [41,55,56]. The capacity to integrate digital tools across organizational boundaries determines firms’ flexibility and innovation capacity [57].

Furthermore, information processing theory emphasizes the importance of mechanisms that allow effective absorption and interpretation of external information. In digitally complex environments, information processing capabilities directly influence the quality of execution and, consequently, firm performance [58,59].

Thus, the range of digitalization acts as a realization mechanism of strategic emphasis and serves as a critical path linking digital strategies to performance outcomes. These two elements—strategic direction and internal capability—are mutually reinforcing.

2.4. Knowledge Sharing as a Moderating Variable

Knowledge sharing within organizations functions as a key moderating mechanism in the digital transformation–performance link. Since digital transformation affects the entire organization, effective use of technology requires seamless circulation of information and knowledge among employees [15,60].

The knowledge-based view considers knowledge as a strategic asset, and efficient knowledge management is directly tied to firm competitiveness [18,61]. In digital transformation processes that require cross-functional collaboration, knowledge sharing enhances adaptability and utilization of digital tools, enabling problem-solving and the discovery of new opportunities [13,14,62,63,64].

However, knowledge sharing is not universally beneficial. When information is overly abundant or unstructured, it can lead to cognitive overload, confusion in decision-making, and redundancy, thereby weakening the impact of the range of digitalization on performance [19,20,21,65].

Thus, knowledge sharing serves as a context-sensitive moderator that may amplify or attenuate the relationship between implementation capabilities and performance, depending on how it is managed [66,67].

2.5. Industrial Sector as an External Institutional Context

For digital transformation to lead to firm performance, not only internal factors but also the characteristics of the external environment must be considered. Even with the same level of execution capabilities and knowledge sharing structures, performance outcomes may vary depending on the industry sector [28,29].

Institutional theory suggests that organizational behavior is shaped by normative, coercive, and mimetic pressures exerted by the external environment [68]. Industry sector serves as a primary domain where such institutional pressures operate, and dictates different levels and directions of digitalization.

For instance, the tourism sector faces strong institutional demands for digitalization due to real-time customer interactions, personalized services, and global competition [30,69,70,71,72]. In contrast, sectors like agriculture or manufacturing face weaker external pressure, resulting in slower digital transitions.

Accordingly, the industry sector functions as an external contextual moderator that influences the level of strategic emphasis on digitalization, the range of digitalization, and the utilization of internal capabilities. A context-sensitive approach that considers institutional environments is crucial for interpreting heterogeneous performance outcomes in digital transformation [16,73].

3. Hypothesis Development

According to the diffusion of innovations theory [12], an organization’s strategic intention and emphasis on adopting new digital technologies play a critical role in expanding the scope of digitalization within the firm. In environments where top management deliberately promotes innovation adoption, digital technologies tend to diffuse more rapidly and broadly [12]. Firms that prioritize digital transformation foster internal conditions that enhance awareness, motivation, and resource allocation toward digital initiatives. This strategic emphasis not only accelerates the adoption rate but also broadens the diversity of digital technologies implemented [44].

Moreover, the organizational readiness for change theory [48] posits that organizations that explicitly emphasize the importance of digitalization improve their collective readiness, comprising the motivation and capability to implement change. High readiness enables effective resource deployment, encourages experimentation with digital solutions, and facilitates the emergence of an adaptive organizational culture [48,74].

H1.

Emphasis on digitalization will positively affect the range of digitalization within a firm.

The resource-based view (RBV) of the firm [53] suggests that organizational performance is determined by valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources and capabilities. When strategically emphasized, digitalization becomes a critical organizational resource, enhancing efficiency, agility, and sustainable competitive advantage [25,75].

Furthermore, dynamic capabilities theory [76] asserts that firms that actively prioritize digitalization strengthen their ability to adapt to market changes and leverage emerging technologies. These capabilities drive innovation, resource reconfiguration, and long-term performance gains [41].

Institutional theory also explains how top management’s emphasis on digitalization facilitates the alignment of organizational practices with evolving market expectations, regulatory requirements, and industry norms [68]. Such alignment enhances legitimacy and competitive positioning, ultimately improving firm performance.

H2.

Emphasis on digitalization will positively affect firm performance.

The positive relationship between the range of digitalization and firm performance can be explained by information processing theory [77,78], which argues that firms require enhanced information-processing capacity in increasingly complex environments. Broader digital adoption enables firms to more effectively gather, analyze, and respond to environmental data, enhancing decision-making quality and performance [79].

From the RBV perspective, adopting a wide range of digital technologies offers heterogeneous resources that are difficult to imitate, such as advanced customer relationship management, data analytics capabilities, and operational efficiency [25,53]. These resources contribute to sustainable competitive advantages and superior firm outcomes [75].

Dynamic capabilities theory also suggests that firms with broader digitalization scopes can continuously adjust their operational processes in response to external change, resulting in increased agility and performance [41].

H3.

The range of digitalization will positively affect firm performance.

Strategic emphasis on digitalization encourages firms to develop advanced technological capabilities, which, in turn, enhance organizational performance through improvements in operational efficiency, innovation, and agility [76]. However, organizational information processing theory [77,78] posits that organizational effectiveness depends on the alignment between information-processing requirements and capacities. As digitalization becomes a strategic priority, the volume and complexity of information that employees must handle tend to increase [65].

While knowledge sharing is generally beneficial for organizational learning and innovation [17], its positive impact can diminish when unstructured or excessive, especially in digitally complex environments. Uncontrolled knowledge flows may lead to cognitive overload, conflicting priorities, fragmented information, and reduced strategic clarity, thereby undermining the overall execution of digital initiatives [20,80,81,82].

Furthermore, cognitive load theory [19] emphasizes that individuals have limited cognitive resources for processing information. In contexts where employees are tasked with complex digital initiatives, excessive knowledge sharing may overburden their cognitive capacity, impair concentration on strategic tasks, and negatively impact overall performance [83]. Therefore, when knowledge sharing is unstructured or excessive, the positive impact of strategic emphasis on digitalization may be diminished [84]. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4a.

Knowledge sharing negatively moderates the relationship between strategic emphasis on digitalization and firm performance.

According to the resource-based view, diverse digital technologies represent valuable organizational assets that can enhance core capabilities such as operational flexibility, customer responsiveness, and efficient resource utilization [25]. However, effective use of such assets requires a well-structured knowledge management process [60].

Organizational learning theory [85] asserts that firms must strike a balance between exploration (e.g., adoption of new digital technologies) and exploitation (e.g., optimization of existing capabilities). When firms adopt a broad range of digital tools without structured knowledge systems, internal stickiness may increase and exploitation of digital capabilities may be obstructed. This is particularly problematic when multiple digital initiatives coexist, creating information overload and organizational misalignment [65,86].

Moreover, “internal stickiness”—the difficulty of transferring knowledge within an organization [86]—tends to become more pronounced as digital transformation efforts expand. Excessive and unstructured knowledge sharing can lead to bottlenecks, confusion, and integration failures, ultimately undermining the performance benefits of digital diversity [17,20]. Therefore, knowledge sharing without strategic coordination may limit the effectiveness of digitalization. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4b.

Knowledge sharing negatively moderates the relationship between the range of digitalization and firm performance.

Institutional theory [68] suggests that strategic decisions and implementation, including digital transformation, are strongly influenced by the institutional context in which organizations operate. Industry-specific characteristics such as regulatory frameworks, competitive intensity, consumer expectations, and technological demands generate institutional pressures that lead to variation in organizational behaviors across sectors [87].

The tourism industry, characterized by high levels of customer interaction, demand for service innovation, and intense global competition, faces strong pressure to adopt digital technologies proactively and broadly [69]. For tourism firms, digitalization serves as a critical enabler of personalized service delivery, real-time responsiveness, and service flexibility—factors that enhance customer experience [88]. As a result, firms in this sector are more likely to emphasize digitalization strategically and adopt a broader array of digital technologies.

By contrast, firms in non-tourism industries—especially those with fewer direct customer interactions and lower service differentiation requirements—tend to face less institutional pressure for digital transformation [21]. These firms may adopt digitalization initiatives more selectively, focusing on cost control, operational efficiency, or incremental improvement rather than competitive differentiation.

Thus, institutional differences between the tourism and non-tourism sectors are expected to lead to significant disparities in both the strategic emphasis on digitalization and the range of digital technologies adopted. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5a.

The level of strategic emphasis on digitalization differs significantly between the tourism and non-tourism sectors.

H5b.

The range of digitalization differs significantly between the tourism and non-tourism sectors.

4. Methodology

Multiple measurement items and their associated scales were adopted from established prior studies to test the proposed hypotheses. All constructs were assessed using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly Agree”).

Given the study’s aim to examine conditional and causal relationships among variables, moderation analysis was employed as a key methodological approach. All statistical analyses, including linear regression, moderation analysis, and structural equation modeling (SEM), were conducted using Stata 17. This technique was deemed appropriate for yielding statistically robust, valid, and replicable results.

To test the hypotheses, analyses were conducted to examine the effect of industry sector (IS) on both emphasis on digitalization (ED) and the range of digitalization (RD), comparing tourism and non-tourism MSEs. Firms with more than 20 employees were classified as medium-sized, based on the Bhutanese market context, and were excluded from the analysis.

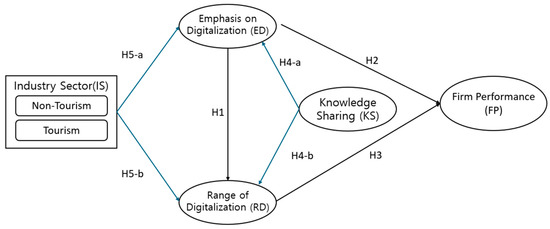

In addition, moderation analyses were conducted to evaluate the moderating effect of knowledge sharing (KS) on the relationships between ED and firm performance (FP), as well as between RD and FP. These relationships and constructs are visually summarized in the research model presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework methodology.

4.1. Data Collection

This study aims to provide empirical evidence on how the emphasis placed on digital diffusion and the range of technologies adopted influence firm performance among Bhutanese MSEs. Accordingly, data were collected from individuals who either owned, managed, or had direct family involvement in the control of a micro or small enterprise.

To ensure the relevance of respondents, a qualifying question was included on the opening screen of the online survey. Specifically, participants were asked: “Do you (or your family member) manage or own a very small, small, or medium-sized business”? Respondents who answered “No” were automatically exited from the survey, ensuring that only eligible individuals proceeded.

Those who answered affirmatively were subjected to a second screening step. In this step, participants were asked to indicate the size of their business by selecting one of the following categories: micro (1–9 employees), small (10–20 employees), or medium (21–60 employees). Respondents who selected “Medium” were excluded from the final dataset.

Initial outreach to potential respondents was conducted through WeChat groups targeting business owners and operators in Bhutan. The survey software included IP tracking functionality to prevent multiple submissions from the same device while preserving respondent anonymity. In total, 225 responses were received. The data were collected over a 21-day period from December 2024 through early January 2025. Of these, 8 responses were removed due to either classification as medium-sized enterprises (defined as firms with 20 or more employees in the Bhutanese context) or due to incomplete survey submissions. This resulted in a final sample of 217 valid responses for analysis.

4.2. Survey Instrument

The constructs used in this study—emphasis on digitalization (ED), range of digitalization (RD), firm performance (FP), and knowledge sharing (KS)—were measured using survey items adapted from previously validated instruments used in related empirical studies. The constructs of ED and RD were operationalized based on survey items developed by Dai et al. [89], Gogus [47], Zhu et al. [90], and Choudrie et al. [91]. ED measured the degree to which the firm prioritizes digital transformation, while RD captured the breadth of digital technologies applied within the firm.

Firm performance (FP) was measured using a set of key performance indicators (KPIs) representing both financial and non-financial dimensions of value creation. These items were adapted from previously established instruments used in studies by Bressolles and Lang [92], Ho, Lai, Hou, and Zhang [56], and Okudan et al. [93]. To assess knowledge sharing (KS), this study adopted survey items validated in prior research by Marjerison, Andrews, and Kuan [14]. All items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly Agree”).

4.3. Variables

4.3.1. KPIs as Indicators of Value Creation

There is currently no scholarly consensus on a standardized single metric for measuring the value created through digital technology adoption. In this study, firm performance is operationalized using a composite measure of nine key performance indicators (KPIs). These indicators are designed to capture both financial and non-financial aspects of value creation resulting from digital technology adoption within MSEs.

4.3.2. Emphasis on Digital Digitalization

The construct of emphasis on digitalization (ED) refers to the degree of strategic priority and urgency that a firm places on adopting digital technologies. This variable is measured using eight dimensions originally proposed by Matt et al. [94] and adapted in the context of MSEs by Chen and Guo [95]. These dimensions capture the firm’s managerial commitment, perceived necessity, and urgency to implement digital solutions across business operations.

4.3.3. Range of Digitalization

The range of digitalization (RD) captures the breadth and variety of digital technologies implemented within a firm. Drawing on the work of Bilal et al. [96], this construct includes nine categories of digital technologies: enterprise software, big data analytics, digital connectivity within production phases, digital connectivity with suppliers, e-commerce platforms, social media use, digital connectivity with customers, intranet-based platforms, and cloud computing and applications. This multidimensional perspective reflects the extent to which firms integrate diverse digital tools across internal and external business processes. The constructs, measurement items, and corresponding references are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Construct Measurement and Sources.

4.4. Sampling

The final sample for this study consisted of 217 valid responses from MSEs in Bhutan. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 2. Generation was classified as follows: 1965–1980 (Generation X), 1981–1995 (Generation Y or Millennials), and 1996–2006 (Generation Z), with any remaining responses categorized as ‘Others’. In terms of generational distribution, the sample was relatively balanced across Generation X (34.1%), Generation Y (34.6%), and Generation Z (31.3%), enabling a multigenerational perspective on digital adoption.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents (N = 217).

Regarding the firm’s size, 51.2% of the sample were classified as micro enterprises, while the remaining 48.8% were small enterprises. No medium-sized enterprises were included in the final dataset, as those were excluded by design. The industry distribution shows that 41.5% of respondents operated in the tourism sector, while 58.5% belonged to non-tourism industries. No responses were categorized under “Other”. In terms of business maturity, 29.0% of firms had been in operation for less than two years, 29.0% between 2–5 years, 27.6% between 6–10 years, and 14.3% had more than 10 years of operational history. This distribution provides insight into both early-stage and more established MSEs.

4.5. Reliability Analysis

To assess the internal consistency of the constructs used in the study, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each multi-item scale. Cronbach’s alpha is a commonly used measure of reliability that evaluates how closely related a set of items are as a group. As suggested by Pallant [97], values above 0.70 are considered acceptable for exploratory research, while values above 0.80 are preferable for established measures.

As shown in Table 3, all scales demonstrated excellent reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.990 to 0.994, indicating that the items within each construct consistently measured the intended concepts. These results confirm the appropriateness of the scales for further statistical analysis.

Table 3.

The effect of emphasis on digitalization on the range of digitalization.

5. Results

5.1. Direct Effects

5.1.1. The Effect of Emphasis on Digitalization on Range of Digitalization (H1)

A simple linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the effect of emphasis on digitalization on the range of digitalization (Table 4). The model was statistically significant, F(1, 215) = 392.17, p < 0.001, explaining 64.6% of the variance in the range of digitalization. Emphasis on digitalization had a significant positive effect on the range of digitalization, β = 0.96, p < 0.001. Thus, hypothesis H1 was supported. This result suggests that firms that view digitalization as a core strategic priority are likely to adopt nearly twice as many digital technologies compared to firms with lower digital emphasis, thereby expanding their operational digital coverage.

Table 4.

Reliability analysis for the scales used in this study.

5.1.2. The Effect of Emphasis on Digitalization on Firm Performance (H2)

A simple linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the effect of emphasis on digitalization on firm performance (Table 5). The model was statistically significant, F(1, 215) = 239.09, p < 0.001, explaining 52.6% of the variance in firm performance. Emphasis on digitalization had a significant positive effect on firm performance, B = 0.78, p < 0.001. Thus, hypothesis H2 was supported. This implies that strategic digitalization is not only about technology adoption, but it also drives tangible performance improvements, potentially through increased efficiency, innovation, or market responsiveness.

Table 5.

The effect of emphasis on digitalization on firm performance.

5.1.3. The Effect of Range of Digitalization on Firm Performance (H3)

A simple linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the effect of the range of digitalization on firm performance (Table 6). The model was statistically significant, F(1, 215) = 238.80, p < 0.001, explaining 52.6% of the variance in firm performance. The range of digitalization had a significant positive effect on firm performance, B = 0.65, p < 0.001. Thus, hypothesis H3 was supported. This indicates that adopting a broader portfolio of digital technologies tends to be associated with stronger firm performance outcomes, reflecting the value of digital diversity.

Table 6.

The effect of the range of digitalization on firm performance.

5.2. Moderating Effects

5.2.1. The Moderating Effect of Knowledge Sharing on Emphasis on Digitalization and Firm Performance (H4a)

Moderation analysis indicated a statistically significant overall model, F(3, 213) = 1168.45, p < 0.001, explaining 94.97% of the variance. The interaction between knowledge sharing and emphasis on digitalization was significant (B = −0.03, p = 0.016), indicating knowledge sharing negatively moderated this relationship. Thus, hypothesis H4a was supported (Table 7). This means that even when digitalization is emphasized strategically, excessive or poorly structured knowledge sharing can dilute its positive effects on performance by creating ambiguity or overload.

Table 7.

The moderating effect of knowledge sharing on the relationship between emphasis on diffusion and firm performance.

5.2.2. The Moderating Effect of Knowledge Sharing on the Range of Digitalization and Firm Performance (H4b)

Moderation analysis showed a statistically significant overall model, F(3, 213) = 1259.77, p < 0.001, explaining 94.66% of the variance. The interaction between knowledge sharing and the range of digitalization was significant (B = −0.05, p < 0.001), indicating a negative moderation effect. Thus, hypothesis H4b was supported (Table 8). This suggests that when digital breadth is not accompanied by focused and well-managed knowledge flows, it may overwhelm the organization and reduce the effectiveness of digital tools.

Table 8.

The moderating effect of knowledge sharing on the relationship between the range of digitalization and firm performance.

5.3. Industry Comparison

Two independent sample t-tests were conducted to examine the effect of industry on digital diffusion emphasis and the range of digitalization (Table 9). There were significant differences in both digital diffusion emphasis and the range of digitalization between tourism and non-tourism sectors, with tourism having significantly higher mean scores in both cases. These findings highlight the sectoral divide: tourism firms, likely facing greater institutional and market pressures, are more proactive in both emphasizing and implementing digital technologies. This reflects how external demands shape internal digital strategies.

Table 9.

Results of independent sample t-tests.

Additionally, Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated to determine the practical significance of these differences. Cohen’s d is a standardized measure indicating the magnitude of differences between two groups, where values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 typically represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively. The results indicated very large effect sizes for both digital diffusion emphasis (Cohen’s d = 2.28) and the range of digitalization (Cohen’s d = 3.77), clearly demonstrating substantial practical differences between the two industry sectors. Therefore, hypotheses H5a and H5b are strongly supported.

6. Robustness Check

6.1. Robustness Check Using Structural Equation Modeling

To verify the robustness of the main findings, a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was conducted using latent constructs for emphasis on digitalization (ED), range of digitalization (RD), and firm performance (FP). This method provides a more rigorous analytical framework than the regression-based models presented earlier as it explicitly accounts for measurement error and allows for the estimation of relationships among unobserved (latent) variables. In survey-based research where constructs are measured through multiple indicators, SEM serves as an important robustness check by enhancing the reliability and validity of structural relationships.

The SEM results (Table 10) offer strong and consistent support for the first three hypotheses. Specifically, strategic emphasis on digitalization had a significant positive effect on the range of digital technologies adopted (β = 0.811, p < 0.001), supporting H1. This confirms that when digitalization is prioritized at the strategic level, firms are more likely to adopt a broader set of digital tools. In addition, both strategic emphasis (β = 0.407, p < 0.001) and range of digitalization (β = 0.401, p < 0.001) were found to significantly enhance firm performance, thus supporting H2 and H3. These findings are consistent with those obtained from the regression analyses, indicating that the theorized relationships are not artifacts of specific model specifications or aggregation techniques.

Table 10.

SEM results for H1–H3.

Moreover, key model fit indices indicated an excellent overall fit between the data and the hypothesized model. This reinforces the validity of the structural relationships proposed in the theoretical framework. The convergence of results across both regression and SEM approaches strengthens the empirical credibility of the study and confirms the internal consistency of the underlying model. In sum, the SEM-based robustness check validates the original hypotheses, provides deeper insights into the structural relationships among key constructs, and ensures that the findings are not sensitive to estimation methods.

6.2. Robustness Validation Through Multigroup SEM: Sectoral Heterogeneity in Digitalization Effects

To further assess the robustness of the industry sector effects hypothesized in H5a and H5b, a multigroup structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was conducted by dividing the sample into tourism and non-tourism sectors (Table 11). This method enables a direct comparison of structural path coefficients across groups and allows us to test whether the strength and significance of relationships differ depending on industry context.

Table 11.

Sectoral heterogeneity in digitalization effects for H5a and b.

The results reveal clear support for H5a. Specifically, the path from emphasis on digitalization (ED) to the range of digitalization (RD) was significantly stronger in the tourism group (β = 0.884, p < 0.001) compared to the non-tourism group (β = 0.322, p < 0.001), reinforcing the earlier finding that institutional and market pressures in the tourism sector drive greater digital adoption breadth. This confirms that the relationship between strategic digital emphasis and digital implementation varies by industry sector, as originally proposed in the hypothesis.

In contrast, H5b was not supported in the multigroup SEM results. The path from RD to firm performance (FP) was statistically insignificant in both the tourism and non-tourism groups (p > 0.05), indicating that the performance returns from broad digital adoption do not vary meaningfully between sectors. This deviates from the initial t-test results that showed higher average RD scores for tourism firms, suggesting that while adoption levels differ, the effectiveness of those adoptions on performance may not. One possible explanation for the lack of sectoral difference in the RD–FP relationship is that the effectiveness of digital adoption may depend more on internal organizational capabilities such as absorptive capacity and change management maturity than on sectoral affiliation alone. Although tourism firms adopt a broader range of digital tools, their ability to realize performance benefits may be constrained by limited human capital, digital literacy gaps, or integration challenges, particularly in resource-scarce environments like Bhutan.

Moreover, external institutional conditions such as uneven digital infrastructure, inconsistent access to training, and varying customer readiness may suppress sector-based differences in digital performance outcomes. While sectoral affiliation appears to influence the extent of adoption, it may not translate directly into measurable performance gains. These findings suggest that the link between digital adoption and firm performance is likely mediated or moderated by unobserved factors such as employee competencies, leadership commitment, or customer engagement, which were not explicitly modeled in this study.

The application of multigroup SEM as a robustness check provides a theoretically grounded and statistically rigorous way to examine cross-sectoral differences in the digitalization–performance linkage. The results confirm H5a, showing that the relationship between strategic emphasis on digitalization and the range of digital technologies adopted is significantly stronger in the tourism sector (0.884) than in the non-tourism sector (0.322). This finding reinforces the notion that institutional and market-specific pressures in service-intensive industries like tourism promote more extensive digital adoption when strategic emphasis is high.

However, the relationship between the range of digitalization and firm performance (H5b) was not statistically significant in either sector. While this might suggest that broader digital adoption does not directly lead to performance gains, the lack of significance could also be due to sample size limitations or sector-specific mediating factors not accounted for in the current model. Therefore, H5b should be interpreted with caution. Rather than concluding a definitive lack of relationship, these findings indicate that the performance effects of digital breadth may be more complex and context-dependent than originally hypothesized.

7. Discussion

This study deepens the understanding of how strategic emphasis on digitalization and the range of digital technology adoption influence firm performance among MSEs in Bhutan. These findings clarify how digitalization contributes to value creation when aligned with internal capabilities and external pressures [25]. Specifically, firms that place greater strategic emphasis on digitalization are more likely to adopt a broader set of technologies, a pattern that reflects how managerial commitment facilitates organizational adaptation and integration. This highlights a practical pathway through which strategic intent translates into operational breadth, especially in resource-constrained environments such as Bhutanese MSEs [32].

Although both strategic emphasis and digital breadth were positively associated with overall firm performance, multigroup SEM results showed that the relationship between digital breadth and performance was not statistically significant in either the tourism or non-tourism sector [35]. This suggests that simply adopting a wider range of technologies does not guarantee performance benefits across all contexts. One plausible explanation is that firms may lack the absorptive capacity needed to effectively integrate and utilize digital tools [59], particularly in environments with limited digital infrastructure or workforce capabilities. In addition, the benefits of digital breadth may take time to materialize and may not be captured in cross-sectional data [98]. Prior studies also highlight the role of strategic alignment and process readiness in turning digital adoption into actual value [25]. The non-significant result may, therefore, reflect a mismatch between digital adoption and organizational readiness, emphasizing the need for future research to examine sector-specific mediators and temporal factors more closely.

These sector-specific discrepancies also contrast with evidence from more digitally advanced economies. For example, studies in Spain [99] and Singapore [100] report more consistent performance improvements associated with digital breadth, often due to stronger innovation systems, digital infrastructure, and government incentives. Similarly, in high-tech environments such as South Korea, digital transformation tends to yield more uniform returns across industries due to national-level coordination and policy alignment [101]. Compared to these settings, the Bhutanese MSE ecosystem presents a more fragmented institutional environment, which may constrain the full realization of digital benefits and explain the performance inconsistencies observed.

Moreover, this study identifies knowledge sharing as a potential risk factor rather than a universal benefit. While it is generally considered a key enabler of organizational learning, excessive or poorly structured knowledge flows, especially in digitally complex environments, may lead to cognitive overload, role ambiguity, and impaired strategic execution. These findings underscore the need for well-structured knowledge systems that facilitate rather than obstruct digital transformation.

Industry context further emerges as a key variable shaping digital behavior. Tourism sector firms exhibit markedly higher levels of digital emphasis and technology adoption, reflecting the institutional pressures they face due to competitive intensity and customer-facing operations. However, despite these higher adoption levels, the sector did not demonstrate significantly different performance returns. This indicates that the benefits of digitalization may depend more on strategic alignment and absorptive capacity than on the quantity of technologies adopted. This observation also aligns with the findings of Vial [6] who emphasizes that digital transformation success is contingent on internal absorptive capacity and external environmental readiness.

Overall, this study underscores that digital transformation in MSEs is not simply a matter of expanding technological scope. Rather, it requires careful alignment with strategic priorities, organizational capabilities, and the external environment. The sectoral insignificance of digital breadth’s effect on performance further reinforces the point that digital adoption alone is not enough. To fully realize the benefits of digitalization, MSEs must adopt an integrative approach that considers not only which technologies are deployed but also how they are embedded into business processes, knowledge systems, and sector-specific conditions.

7.1. Theoretical Contribution

This study offers important theoretical contributions by extending established frameworks in digital transformation, innovation diffusion, and organizational performance, particularly within the underexplored context of MSEs in emerging economies.

Rather than restating existing models, this study shows how their application reveals context-specific dynamics in Bhutanese MSEs where digital maturity, institutional support, and absorptive capacity are limited yet evolving.

Building on the diffusion of innovations theory [12], this research positions strategic emphasis on digitalization not just as a trigger for adoption but also as a form of internal innovation governance. Firms that actively prioritize digital transformation tend to adopt a broader range of technologies, highlighting that top-down commitment can compensate for institutional voids or infrastructure gaps. This expands Rogers’ framework by demonstrating its applicability in environments where change is initiated internally, rather than imposed externally.

The study also contributes to the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities theory by demonstrating that both strategic emphasis and the breadth of digital adoption function as non-physical, strategic assets. These intangible capabilities enhance firm performance when aligned with firm-specific conditions. In contrast to the traditional assumption that resource constraints inhibit innovation, this study finds that even modest digital strategies can generate value if they are well aligned and embedded. Moreover, the multigroup SEM results reveal that digital breadth does not guarantee performance gains across all sectors, suggesting that dynamic capabilities require both technological variety and contextual fit.

With respect to information processing theory, the study underscores the risks of unstructured knowledge sharing during digital transformation. While knowledge flows are generally beneficial, excessive or poorly managed sharing can lead to cognitive overload and diminish performance—a boundary condition often overlooked in SME research. This contribution highlights the importance of aligning digital expansion with internal decision-making capacity.

Finally, this study enriches the institutional theory by showing how industry-specific pressures shape strategic emphasis and digital adoption. Tourism sector firms, facing higher institutional expectations for service responsiveness and customer experience, exhibited stronger digital commitment. Yet, performance gains were not proportionate to adoption levels. This suggests that institutional pressure may drive adoption without guaranteeing value realization. This distinction contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how external legitimacy pressures influence internal transformation.

Together, these insights support a more integrated theoretical framework for digital transformation, one that connects strategic intent, resource configuration, information processing, and institutional context. By doing so, the study advances the discourse on digitalization by demonstrating how MSEs can activate strategic mechanisms even under conditions of resource scarcity and institutional fragmentation.

7.2. Practical Contribution and Policy Implications

This study yields several practical implications for business practitioners and policymakers seeking to drive digital transformation among MSEs, particularly in emerging markets like Bhutan.

For practitioners, the findings reinforce the importance of strategic emphasis on digitalization. Firms that position digital transformation as a core strategic priority, rather than merely a technical upgrade, are more likely to adopt a broader range of digital tools and experience performance improvements. Managers should embed digitalization into the organizational vision, allocate sufficient resources, and cultivate a digital-first mindset across business functions. Building integrated digital infrastructures instead of relying on isolated tools can enhance customer engagement, internal coordination, and supply chain responsiveness.

Although broader digital adoption was generally linked to higher performance in regression models, the sector-specific structural equation modeling results revealed no consistent performance benefits across industries. This suggests that expanding digital tools may not yield uniform gains, particularly if firms lack sector-appropriate capabilities or enabling conditions. Therefore, adoption breadth should be guided by strategic alignment and organizational readiness.

The study also highlights potential risks associated with unstructured knowledge sharing. While the flow of knowledge facilitates innovation, excessive or poorly managed sharing during digital initiatives can result in cognitive overload and decision-making ambiguity. Firms are encouraged to implement structured knowledge management systems, such as role-specific filters or designated curators, to ensure that relevant and timely information supports rather than hinders implementation.

From a policy perspective, the pronounced differences between tourism and non-tourism sectors point to the need for sector-sensitive interventions. Tourism firms demonstrated higher digital maturity, likely in response to stronger market and institutional pressures. Non-tourism MSEs may require targeted support, including digital training, financial incentives, or easier access to sector-appropriate technologies, to address structural challenges.

In addition, policymakers should adopt a differentiated approach to digital transformation. MSEs differ in terms of digital maturity and resource availability, and uniform strategies are unlikely to succeed. Tiered or modular policy frameworks, supported by public and private collaboration in infrastructure development and training programs, can promote scalable and context-specific digital advancement.

In sum, digital transformation in MSEs demands more than access to technology. It requires strategic clarity, integrated execution, effective knowledge management, and supportive institutional frameworks. Aligning managerial practices and policy tools with these principles is essential to unlocking the full potential of digitalization in resource-constrained environments.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers meaningful theoretical and practical insights, several limitations should be acknowledged, each pointing to productive avenues for future research. The use of a cross-sectional research design limits the ability to establish causality or track how digital strategies evolve and influence performance over time. Future research would benefit from longitudinal or panel data to capture the dynamic nature of digital transformation in small firms.

Additionally, relying on self-reported measures for key constructs such as firm performance, digital emphasis, and knowledge sharing may introduce response biases. Incorporating objective indicators like financial records, customer retention, or operational metrics could improve measurement validity and strengthen perception-based findings.

The study’s focus on Bhutanese micro and small enterprises provides insights into an underrepresented context but may limit generalizability to other economies. Cross-national or cross-regional comparisons would help clarify how institutional maturity or infrastructure influences digital adoption outcomes. Moreover, categorizing firms solely into tourism and non-tourism sectors may overlook important differences within sectors. Future studies could adopt more refined industry classifications to reflect variation in digital needs, customer engagement models, and innovation demands more accurately.

Finally, although knowledge sharing is treated as a moderator, this study does not distinguish between different modes or structures of sharing, such as formal and informal or vertical and lateral exchanges. Future work could explore how specific knowledge-sharing mechanisms interact with digital initiatives, especially in resource-constrained settings where informal communication is common.

Taken together, addressing these limitations can help build a more nuanced and context-sensitive understanding of the mechanisms and conditions through which digital transformation enhances small firm performance.

8. Conclusions

This study investigated how strategic emphasis on digitalization and the range of technology adoption shape firm performance among MSEs in Bhutan, considering the moderating role of knowledge sharing and the influence of sectoral context. Drawing on multiple theoretical frameworks, the findings reveal that while strategic emphasis and digital breadth are generally associated with enhanced performance, their effects are conditioned by internal knowledge flows and external industry environments.

The results emphasize that digital transformation is not simply a matter of adopting more technologies but of strategically embedding those technologies into the organizational fabric. Knowledge sharing, while beneficial in principle, may hinder performance when unstructured or excessive. Similarly, sectoral pressures explain differences in digital engagement, though not necessarily in performance outcomes.

By integrating insights from innovation diffusion, dynamic capabilities, and institutional theory, the study provides a multidimensional view of digital transformation in emerging markets. It highlights the need for nuanced managerial strategies and policy frameworks that align digital priorities with firm capabilities and contextual realities.

Limitations such as cross-sectional design, reliance on self-reports, and sectoral simplification suggest directions for future research, including longitudinal analysis, incorporation of objective metrics, and more granular industry segmentation. Addressing these gaps will further clarify how digital transformation unfolds across varied organizational and institutional contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K.M. and J.M.K.; methodology, J.M.K.; software, J.M.K.; validation, R.K.M., J.Y.J. and J.M.K.; formal analysis, J.M.K.; investigation, R.K.M.; resources, R.K.M.; data curation, J.M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.M. and J.M.K.; writing—review and editing, J.Y.J.; visualization, J.M.K.; supervision, R.K.M.; project administration, R.K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional IRB Statement, WKUIRB2025-002, is available upon request.

Data Availability Statement

The data gathered and used in this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ivascu, L.; Doina, B.; Ivascu, L.C. Digital Transformation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Skare, M.; de Obesso, M.d.l.M.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. Digital transformation and European small and medium enterprises (SMEs): A comparative study using digital economy and society index data. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 68, 102594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Kiani, A.; Rashid, M. Is data the key to sustainability? The roles of big data analytics, green innovation, and organizational identity in gaining green competitive advantage. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.; Yang, D.; Ghani, U.; Hughes, M. Entrepreneurial passion and technological innovation: The mediating effect of entrepreneurial orientation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 34, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Dong, J.Q.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. In Managing Digital Transformation; Warner, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 13–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, H. The impact of service R&D on the performance of Korean information communication technology small and medium enterprises. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2011, 28, 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Hitt, L.M. Computing productivity: Firm-level evidence. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2003, 85, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Slimane, S.; Coeurderoy, R.; Mhenni, H. Digital transformation of small and medium enterprises: A systematic literature review and an integrative framework. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2022, 52, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Ma, L. Research on successful factors and influencing mechanism of the digital transformation in SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahadat, M.H.; Nekmahmud, M.; Ebrahimi, P.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Digital technology adoption in SMEs: What technological, environmental and organizational factors influence in emerging countries? Glob. Bus. Rev. 2023, 09721509221137199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aydiner, A.S.; Tatoglu, E.; Bayraktar, E.; Zaim, S.; Delen, D. Business analytics and firm performance: The mediating role of business process performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjerison, R.K.; Andrews, M.; Kuan, G. Creating sustainable organizations through knowledge sharing and organizational agility: Empirical evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-M.; Wang, Y.-C. Determinants of firms’ knowledge management system implementation: An empirical study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrani, N.; Rejeb, N.; Maalaoui, A.; Dabić, M.; Kraus, S. Drivers of digital transformation in SMEs. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 71, 5030–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L.; Ingram, P. Knowledge transfer: A basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2000, 82, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, A.J. A comparative analysis of the usage and infusion of wiki and non-wiki-based knowledge management systems. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2011, 12, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, M.R.; Hansen, M.T. Different knowledge, different benefits: Toward a productivity perspective on knowledge sharing in organizations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Kraemer, K.L.; Xu, S. The process of innovation assimilation by firms in different countries: A technology diffusion perspective on e-business. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1557–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ge, S.; Wang, N. Digital transformation: A systematic literature review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 162, 107774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kar, A.K. Why do small and medium enterprises use social media marketing and what is the impact: Empirical insights from India. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.-J.A.; Yen, M.-H.; Bourne, M. How rival partners compete based on cooperation? Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.S. A resource-based perspective on information technology capability and firm performance: An empirical investigation. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Jiang, X.; Luo, J. Relationship between enterprise digitalization and green innovation: A mediated moderation model. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildt, H. The institutional logic of digitalization. In Digital Transformation and Institutional Theory; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2022; pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, L. The Contingency Theory of Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Contemp. Sociol. 1979, 8, 612–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Michael Hall, C. Sharing versus collaborative economy: How to align ICT developments and the SDGs in tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shouk, M.A.; Lim, W.M.; Megicks, P. Using competing models to evaluate the role of environmental pressures in ecommerce adoption by small and medium sized travel agents in a developing country. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Newby, M.; Macaulay, M.J. Information technology adoption in small business: Confirmation of a proposed framework. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ke, W.; Wei, K.K.; Hua, Z. The impact of IT capabilities on firm performance: The mediating roles of absorptive capacity and supply chain agility. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 54, 1452–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Nevo, S.; Jin, J.; Wang, L.; Chow, W.S. IT capability and organizational performance: The roles of business process agility and environmental factors. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaei, N.; Rezaei, S.; Ismail, W.K.W. Examining learning strategies, creativity, and innovation at SMEs using fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis and PLS path modeling. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobgye, S. Digital Transformation in Bhutan: Culture, Workforce and Training. Ph.D. Dissertation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Autstralia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, A. Digital Transformation for a Sustainable Bhutan. Druk. J. 2020. Available online: https://drukjournal.bt/digital-transformation-for-a-sustainable-bhutan/ (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Brunet, S.; Bauer, J.; De Lacy, T.; Tshering, K. Tourism development in Bhutan: Tensions between tradition and modernity. J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N.; Ramanujam, V. Measurement of business performance in strategy research: A comparison of approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Fornell, C.; Lehmann, D.R. Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Koschate, N.; Hoyer, W.D. Do satisfied customers really pay more? A study of the relationship between customer satisfaction and willingness to pay. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, G.; Bonnet, D.; McAfee, A. Leading Digital: Turning Technology into Business Transformation; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wamba, S.F.; Gunasekaran, A.; Akter, S.; Ren, S.J.-f.; Dubey, R.; Childe, S.J. Big data analytics and firm performance: Effects of dynamic capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoz Barragan, K.; Becker, F.S.R. Keeping pace with the digital transformation—Exploring the digital orientation of SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2024, 64, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogus, A. Shifting to digital: Adoption and diffusion. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.J. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A. Technology Readiness Index (TRI) a multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 2, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. More open, more innovative? CEOs’ openness in promoting digital transformation. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczak, G.; Sultan, F.; Hultink, E.J. Determinants of IT usage and new product performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2007, 24, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebel, T.; O’Mahony, M.; Saam, M. The contribution of intangible assets to sectoral productivity growth in the EU. Rev. Income Wealth 2017, 63, S49–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, G.D.; Grover, V. Types of information technology capabilities and their role in competitive advantage: An empirical study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.; Wäger, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.Y.; Lai, J.H.; Hou, H.; Zhang, D. Key performance indicators for evaluation of commercial building retrofits: Shortlisting via an industry survey. Energies 2021, 14, 7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S.; Meisner, K.; Krause, K.; Bzhalava, L.; Moog, P. Is digitalization a source of innovation? Exploring the role of digital diffusion in SME innovation performance. Small Bus. Econ. 2024, 62, 1469–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammuto, R.F.; Griffith, T.L.; Majchrzak, A.; Dougherty, D.J.; Faraj, S. Information technology and the changing fabric of organization. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Long Range Plan. 1996, 29, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.-L.M.; Horng, J.-S.; Sun, Y.-H.C. Hospitality teams: Knowledge sharing and service innovation performance. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhchy, J.; Chen, G.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, Y.A.; Zhang, J.; Ahmed, M. Dynamic impact of leadership style, knowledge-sharing, and organizational culture on organizational performance. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.t. The impact of knowledge sharing on organizational learning and effectiveness. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppler, M.J.; Mengis, J. The Concept of Information Overload-A Review of Literature from Organization Science, Accounting, Marketing, MIS, and Related Disciplines (2004). In Kommunikationsmanagement im Wandel; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 271–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Li, Y.; Miao, L. The impact of knowledge hiding on targets’ knowledge sharing with perpetrators. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, S.; Zaim, H. Peer knowledge sharing and organizational performance: The role of leadership support and knowledge management success. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2455–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, K.; Buhalis, D.; Inversini, A. Smart tourism destinations: Ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2016, 2, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Sinarta, Y. Real-time co-creation and nowness service: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Technology, ICT and tourism: From big data to the big picture. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstykh, T.; Shmeleva, N.; Boev, A.; Guseva, T.; Panova, S. System Approach to the Process of Institutional Transformation for Industrial Integrations in the Digital Era. Systems 2024, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, M.; Hulland, J. The resource-based view and information systems research: Review, extension, and suggestions for future research. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J. Designing Complex Organizations; Addison Wesley: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Tushman, M.L.; Nadler, D.A. Information processing as an integrating concept in organizational design. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1978, 3, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R.L.; Lengel, R.H. Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly III, C.A. Individuals and information overload in organizations: Is more necessarily better? Acad. Manag. J. 1980, 23, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, A.; Morris, A. The problem of information overload in business organisations: A review of the literature. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2000, 20, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, M.; Easterby-Smith, M. Beyond the knowledge sharing dilemma: The role of customisation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2008, 12, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J.; Van Merrienboer, J.J.; Paas, F.G. Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 10, 251–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, T.; Kianto, A. Knowledge processes, knowledge-intensity and innovation: A moderated mediation analysis. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 15, 1016–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulanski, G. Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhofer, B.; Buhalis, D.; Ladkin, A. Smart technologies for personalized experiences: A case study in the hospitality domain. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Feng, Y.; Wang, R.; Jung, J. Enhancing the Digital Inheritance and Development of Chinese Intangible Cultural Heritage Paper-Cutting Through Stable Diffusion LoRA Models. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Dong, S.; Xu, S.X.; Kraemer, K.L. Innovation diffusion in global contexts: Determinants of post-adoption digital transformation of European companies. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudrie, J.; Pheeraphuttranghkoon, S.; Davari, S. The digital divide and older adult population adoption, use and diffusion of mobile phones: A quantitative study. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 673–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressolles, G.; Lang, G. KPIs for performance measurement of e-fulfillment systems in multi-channel retailing: An exploratory study. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okudan, O.; Budayan, C.; Arayıcı, Y. Identification and prioritization of key performance indicators for the construction small and medium enterprises. Tek. Dergi 2022, 33, 12635–12662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, C.; Hess, T.; Benlian, A. Digital transformation strategies. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2015, 57, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Guo, Q. Fintech and MSEs Innovation: An Empirical Analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.17293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Xicang, Z.; Jiying, W.; Sohu, J.M.; Akhta, S. Navigating the manufacturing revolution: Identifying the digital transformation antecedents. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 1775–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Su, F.; Zhang, W.; Mao, J.Y. Digital transformation by SME entrepreneurs: A capability perspective. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 1129–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Acosta, P.; Popa, S.; Palacios-Marqués, D. E-business, organizational innovation and firm performance in manufacturing SMEs: An empirical study in Spain. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2016, 22, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]