The Role of Strategic Orientations in the Relationship Between Adaptive Marketing Capabilities and Ambidexterity in Digital Services Firms: The Case of a Highly Competitive Digital Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

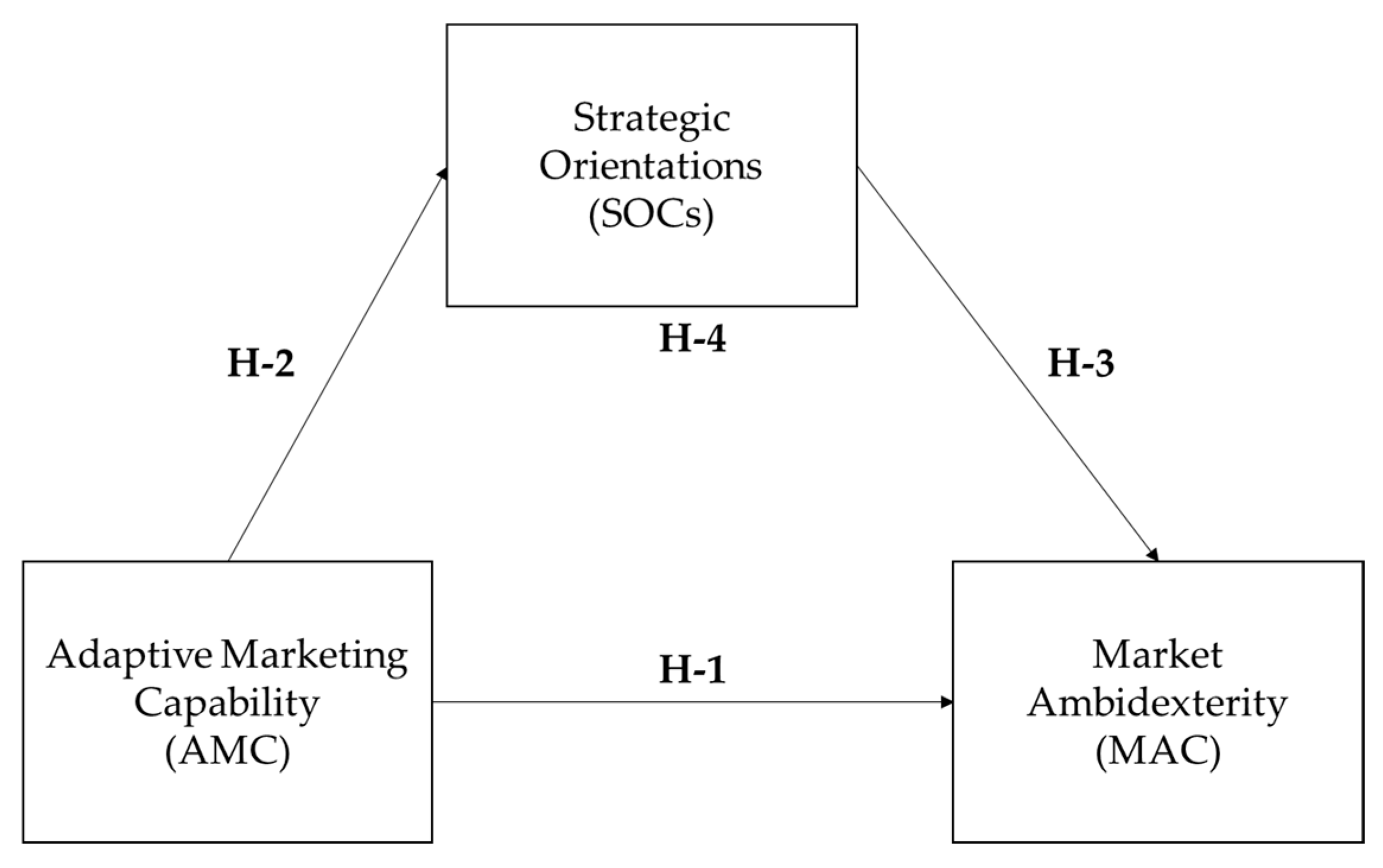

- Is adaptive marketing capability associated with market ambidexterity?

- Is adaptive marketing capability associated with strategic orientations?

- Are strategic orientations associated with market ambidexterity?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Dynamic Capability and Inside-Out and Outside-In Views

2.2. Adaptive Marketing Capability and Digital Product Innovation

2.3. Digital Business Model Innovation and Strategic Orientations

2.4. Adaptive Marketing Capability and Market Ambidexterity

2.5. Adaptive Marketing Capability and Strategic Orientations

2.6. Strategic Orientation and Market Ambidexterity

2.7. The Intervening Role of Strategic Orientations

3. Methodology

Sample Characteristics

4. Analysis

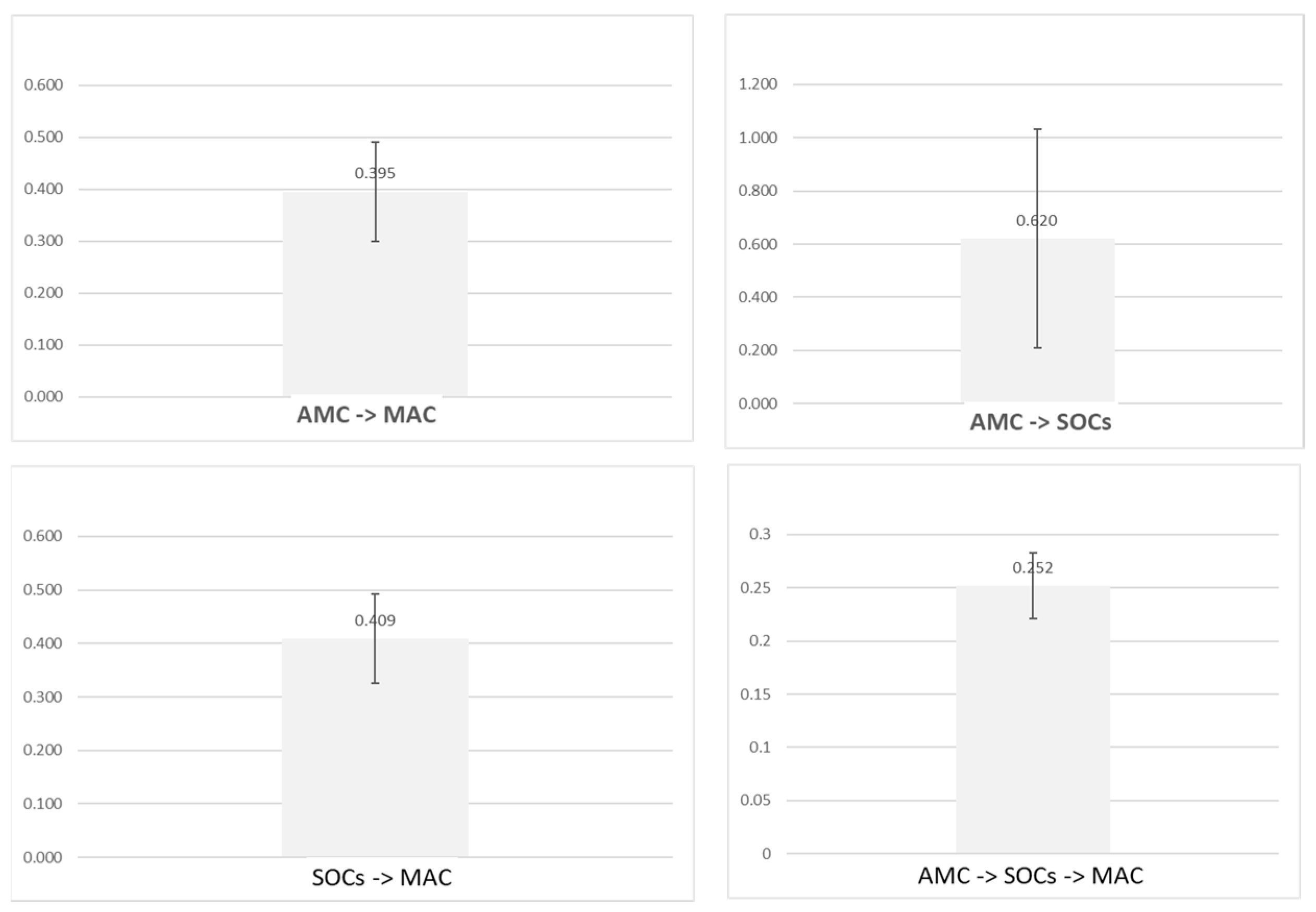

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinterhuber, A.; Vescovi, T.; Checchinato, F. Managing Digital Transformation; Digital Transformation: An overview; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, M.; Wilden, R.; Afshari, L.; Mehralian, G. Dynamic capabilities and innovation ambidexterity: The roles of intellectual capital and innovation orientation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, F.; Münch, C.; Küffner, C.; Hartmann, E. Digital ecosystems and their impact on organizations—A dynamic capabilities approach. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riasanow, T.; Jäntgen, L.; Hermes, S.; Böhm, M.; Krcmar, H. Core, intertwined, and ecosystem-specific clusters in platform ecosystems: Analyzing similarities in the digital transformation of the automotive, blockchain, financial, insurance and IIoT industry. ElectronicMarkets 2021, 31, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachinger, M.; Rauter, R.; Müller, C.; Vorraber, W.; Schirgi, E. Digitalization and its influence on business model inno vation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 1143–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolagar, M.; Parida, V.; Sjödin, D. Ecosystem transformation for digital servitization: A systematic review, integrative frame work, and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Palmié, M.; Wincent, J. How AI capa bilities enable business model innovation: Scaling AI through co-evolutionary processes and feedback loops. J. Bus. Ness Res. 2021, 134, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onamusi, A.B. Adaptive capability, social media agility, ambidextrous marketing capability, and business survival: A mediation analysis. Mark. Brand. Res. 2021, 8, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Baden-Fuller, C.; Teece, D.J. Market sensing, dynamic capability, and competitive dynamics. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed-Dafali, S.; Al-Azad, M.S.; Mohiuddin, M.; Reza, M.N.H. Strategic orientations, organizational ambidexterity, and sustainable competitive advantage: Mediating role of industry 4.0 readiness in emerging markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 401, 136765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Wu, W.; Ali, S. Adaptive marketing capability and product innovations: The role of market ambidexterity and transformational leadership (evidence from Pakistani manufacturing industry). Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 1056–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G. The yin and yang of outside-in thinking. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Bao, Y.; Sekhon, T.; Qi, J.; Love, E. Outside-in marketing capability and firm performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 75, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, A.E.; Polat, V. Strategic orientations, marketing capabilities and innovativeness: An adaptive approach. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, H. Strategic orientations in management literature: Three approaches to understanding the interaction between market, technology, entrepreneurial and learning orientations. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.H.; Kanbach, D.K.; Kraus, S.; Dabić, M. Transform me if you can: Leveraging dynamic capabilities to manage digital transformation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 71, 9094–9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.; K Kanbach, D. Toward an integrated framework of corporate venturing for organizational ambidexterity as a dynamic capability. Manag. Rev. Q. 2022, 72, 1129–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, F.U.; Paul, D.; Henskens, F.; Wallis, M.; Hashmi, M.A. AOSR: An agent oriented storage and retrieval WMS planner for SMEs, associated with AOSF framework, under Industry 4.0. Int. J. Appl. Decis. Sci. 2022, 15, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Linares, R.; Kellermanns, F.W.; López-Fernández, M.C. Dynamic capabilities and SME performance: The moderating effect of market orientation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 59, 162–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.; Osiyevskyy, O.; Agarwal, J.; Reza, S. Does ambidexterity in marketing pay off? The role of absorptive capacity. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Madhavaram, S. Adaptive marketing capabilities, dynamic capabilities, and renewal competences: The “outside vs. inside” and “static vs. dynamic” controversies in strategy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Vahlne, J.E. Dynamic capabilities of emerging market multinational enterprises and the Uppsala model. Asian Bus. Manag. 2020, 21, 690–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiabady, N.; Hadjinicolaou, N.; Din, F.U.; Bhandari, B.; Wu, R.M.; Vakilian, J. Using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to predict organizational agility. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. Closing the marketing capabilities gap. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Day, G.S. Organizing for marketing excellence. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 6–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshima, Y.; Anderson, B.S. Firm growth, adaptive capability, and entrepreneurial orientation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J. Marketing capability, organizational adaptation and new product development performance. Ind. Market. Manag. 2015, 49, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xu, H.; Tang, C.; Liu-Thompkins, Y.; Guo, Z.; Dong, B. Comparing the impact of different marketing capa-bilities: Empirical evidence from B2B firms in China. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 93, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr. Does market orientation matter?: A test of the relationship between positional advantage and performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktemgil, M.; Greenley, G. Consequences of high and low adaptive capability in UK companies. Eur. J. Mark. 1997, 31, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, A.E.; Keskin, H.; Byrne, J.C.; Aren, S. Emotional and learning capability and their impact on product in-novativeness and firm performance. Technovation 2007, 27, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntaş, G.; Semerciöz, F.; Eregez, H. Linking strategic and market orientations to organizational performance: The role of innovation in private healthcare organizations. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. An outside-in approach to resource-based theories. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 42, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Zbaracki, M.J.; Bergen, M. Pricing process as a capability: A resource-based perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouropalatis, Y.; Giudici, A.; Acar, O.A. Business capabilities for industrial firms: A bibliometric analysis of research diffusion and impact within and beyond Industrial Marketing Management. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 83, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. Marketing: The need to contribute to overall business effectiveness. J. Mark. Pract. Appl. Mark. Sci. 1996, 2, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.D.; Lu, R. Performance implications of marketing exploitation and exploration: Moderating role of supplier collaboration. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyinda, C.I.; Opute, A.P.; Fadahunsi, A.; Mbah, C.H. Marketing-sales-service interface and social media marketing influence on B2B sales process. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021, 36, 990–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frau, M.; Moi, L.; Cabiddu, F. Outside-in, inside-out, and blended marketing strategy approach: A longitudinal case study. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2020, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S.; Wensley, R. Marketing theory with a strategic orientation. J. Mark. 1983, 47, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, C.K.; Carvalho, F.M.P.D.O.; Duarte, M.P. Adaptive marketing capabilities, market orientation, and international performance: The moderation effect of competitive intensity. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 2533–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, L.V.; O’Cass, A. In search of innovation and customer-related performance superiority: The role of market orientation, marketing capability, and innovation capability interactions. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 861–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, P.; Souchon, A.L.; Nemkova, E.; Hodgkinson, I.R.; Oliveira, J.S.; Boso, N.; Hultman, M.; Yeboah-Banin, A.A.; Sy-Changco, J. Quadratic effects of dynamic decision-making capability on innovation orientation and performance: Evidence from Chinese exporters. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 83, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Li, C.B. How strategic orientations influence the building of dynamic capability in emerging economies. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F.L. Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Hadaya, P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F.; MacLachlan, D.L. Responsive and proactive market orientation and new-product success. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2004, 21, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Atuahene-Gima, K. Using exploratory and exploitative market learning for new product development. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2010, 27, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J.F., Jr. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Practice 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.X.; Lai, F. Using partial least squares in operations management research: A practical guideline and summary of past research. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, A.; Malter, A.J.; Ganesan, S.; Moorman, C. Cross-sectional versus longitudinal survey research: Concepts, findings, and guidelines. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A., III; Tushman, M.L. Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 8–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, D.; Yaprak, A.; Cavusgil, S.T. Alliance orientation: conceptualization, measurement, and impact on market performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D.R. Bringing corporate culture to the bottom line. Organ. Dyn. 1984, 13, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaswamy, U.S.; Chaudhary, S. Effect of adaptive capability and entrepreneurial orientation on SBU performance: Moderating role of success trap. Manag. Res. Rev. 2022, 45, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.B.; Birkinshaw, J. The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjaningrum, W.D.; Hermawati, A.; Yogatama, A.N.; Puji, R.; Suci, A.P.S. Creative Industry in the Post-Pandemic Digital Era: Meaningful Incubation, Customer Focus, and High Innovation as Strategies to Compete. In ICEBE 2021: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference of Economics, Business, and Entrepreneurship, ICEBE 2021, Lampung, Indonesia, 7 October 2021; European Alliance for Innovation: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2022; p. 317. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L.; Rafiq, M. Ambidextrous organizational culture, Contextual ambidexterity and new product innovation: A comparative study of UK and C hinese high-tech Firms. Br. J. Manag. 2014, 25, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| 51 | 68% |

| 24 | 32% |

| Total: 75 | Total: 100% | |

| Education Level | ||

| 0 | 00.00% |

| 2 | 2.67% |

| 25 | 33.33% |

| 48 | 64.00% |

| 0 | 00.00% |

| Total: 75 | Total: 100% | |

| Position | ||

| 8 | 10.67% |

| 37 | 49.33% |

| 27 | 36.00% |

| 3 | 4.00% |

| Total: 75 | Total: 100% | |

| Years of Experience in the Organisation | ||

| 4 | 5.33% |

| 8 | 10.67% |

| 27 | 36.00% |

| 36 | 48.00% |

| Total: 75 | Total: 100% | |

| Firm Type | ||

| 11 | 14.67% |

| 9 | 12.00% |

| 5 | 6.67% |

| 5 | 6.67% |

| 7 | 9.32% |

| 8 | 10.67% |

| 3 | 4.00% |

| 3 | 4.00% |

| 24 | 32.00% |

| Total: 75 | Total: 100% | |

| Firm Age (Years of Operations) | ||

| 4 | 5.33% |

| 0 | 00.00% |

| 6 | 8.00% |

| 20 | 26.67% |

| 45 | 60.00% |

| Total: 75 | Total: 100% | |

| What is the approximate total number of employees? | ||

| 5 | 6.67% |

| 0 | 00.00% |

| 38 | 50.67% |

| 32 | 42.66% |

| Total: 75 | Total: 100% |

| Construct | Item | AMC | MAC | SOCs | VIF | CR | Alpha | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Loadings | ||||||||

| AMC | VML1 | 0.529 | 0.280 | 0.424 | 1.198 | 0.748 | 0.734 | 0.438 |

| VML2 | 0.603 | 0.394 | 0.414 | 1.215 | ||||

| VML4 | 0.804 | 0.506 | 0.44 | 1.953 | ||||

| AME2 | 0.762 | 0.459 | 0.42 | 1.764 | ||||

| AME3 | 0.669 | 0.402 | 0.327 | 1.468 | ||||

| OM1 | 0.556 | 0.420 | 0.318 | 1.220 | ||||

| MAC | MER1 | 0.591 | 0.744 | 0.437 | 1.386 | 0.707 | 0.692 | 0.45 |

| MER2 | 0.433 | 0.729 | 0.47 | 1.409 | ||||

| MER5 | 0.331 | 0.621 | 0.361 | 1.342 | ||||

| MET1 | 0.500 | 0.674 | 0.389 | 1.282 | ||||

| MET4 | 0.171 | 0.570 | 0.515 | 1.183 | ||||

| SOCs | PMO2 | 0.477 | 0.433 | 0.695 | 1.447 | 0.767 | 0.75 | 0.449 |

| PMO3 | 0.357 | 0.516 | 0.775 | 1.762 | ||||

| RMO3 | 0.453 | 0.482 | 0.741 | 1.536 | ||||

| RMO4 | 0.314 | 0.185 | 0.476 | 1.244 | ||||

| RMO7 | 0.414 | 0.492 | 0.640 | 1.297 | ||||

| Construct | Item Weights and Significance | Individual VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Marketing Capability | ||

| VML1 | 0.219; <0.001 | 1.198 |

| VML2 | 0.253; <0.001 | 1.215 |

| VML4 | 0.297; <0.001 | 1.953 |

| AME2 | 0.276; <0.001 | 1.764 |

| AME3 | 0.229; <0.001 | 1.468 |

| OM1 | 0.232; <0.001 | 1.220 |

| Market Ambidexterity | ||

| MER1 | 0.359; <0.001 | 1.386 |

| MER2 | 0.318; <0.001 | 1.409 |

| MER5 | 0.244; <0.001 | 1.342 |

| MET1 | 0.311; <0.001 | 1.282 |

| MET4 | 0.246; <0.001 | 1.183 |

| Strategic Orientations | ||

| PMO2 | 0.275; <0.001 | 1.447 |

| PMO3 | 0.266; <0.001 | 1.762 |

| RMO3 | 0.283; <0.001 | 1.536 |

| RMO4 | 0.150; <0.001 | 1.244 |

| RMO7 | 0.275; <0.001 | 1.297 |

| IO1 | 0.223; <0.001 | 1.562 |

| AMC | MAC | SOCs | |

| AMC | 0.662 | ||

| MAC | 0.628 | 0.671 | |

| SOCs | 0.593 | 0.642 | 0.670 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | |||||

| AMC -> MAC | 0.381 | 0.395 | 0.139 | 2.743 | 0.006 |

| AMC -> SOCs | 0.593 | 0.620 | 0.066 | 8.932 | 0.000 |

| SOCs -> MAC | 0.416 | 0.409 | 0.143 | 2.899 | 0.004 |

| Total Indirect Effects | |||||

| AMC -> MAC | 0.247 | 0.252 | 0.089 | 2.767 | 0.006 |

| Specific Indirect Effects | |||||

| AMC -> SOCs -> MAC | 0.247 | 0.252 | 0.089 | 2.767 | 0.006 |

| Total Effects | |||||

| AMC -> MAC | 0.628 | 0.647 | 0.081 | 7.779 | 0.000 |

| AMC -> SOCs | 0.593 | 0.62 | 0.066 | 8.932 | 0.000 |

| SOCs -> MAC | 0.416 | 0.409 | 0.143 | 2.899 | 0.004 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Bias | 2.50% | 97.50% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | |||||

| AMC -> MAC | 0.381 | 0.395 | 0.014 | 0.096 | 0.642 |

| AMC -> SOCs | 0.593 | 0.62 | 0.027 | 0.412 | 0.692 |

| SOCs -> MAC | 0.416 | 0.409 | −0.006 | 0.084 | 0.653 |

| Total Indirect Effects | |||||

| AMC -> MAC | 0.247 | 0.252 | 0.006 | 0.031 | 0.396 |

| Specific Indirect Effects | |||||

| AMC -> SOCs -> MAC | 0.247 | 0.252 | 0.006 | 0.031 | 0.396 |

| Total Effects | |||||

| AMC -> MAC | 0.628 | 0.647 | 0.019 | 0.4 | 0.746 |

| AMC -> SOCs | 0.593 | 0.620 | 0.027 | 0.412 | 0.692 |

| SOCs -> MAC | 0.416 | 0.409 | −0.006 | 0.084 | 0.653 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Jabri, M.A.S.; Lahrech, A. The Role of Strategic Orientations in the Relationship Between Adaptive Marketing Capabilities and Ambidexterity in Digital Services Firms: The Case of a Highly Competitive Digital Economy. Systems 2025, 13, 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050358

Al Jabri MAS, Lahrech A. The Role of Strategic Orientations in the Relationship Between Adaptive Marketing Capabilities and Ambidexterity in Digital Services Firms: The Case of a Highly Competitive Digital Economy. Systems. 2025; 13(5):358. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050358

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Jabri, Madhad Ali Said, and Abdelmounaim Lahrech. 2025. "The Role of Strategic Orientations in the Relationship Between Adaptive Marketing Capabilities and Ambidexterity in Digital Services Firms: The Case of a Highly Competitive Digital Economy" Systems 13, no. 5: 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050358

APA StyleAl Jabri, M. A. S., & Lahrech, A. (2025). The Role of Strategic Orientations in the Relationship Between Adaptive Marketing Capabilities and Ambidexterity in Digital Services Firms: The Case of a Highly Competitive Digital Economy. Systems, 13(5), 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13050358