Reimagining Commercial Health Insurance in India: A System-Dynamics Approach to Complex Stakeholder Incentives and Policy Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. System-Dynamics Approach

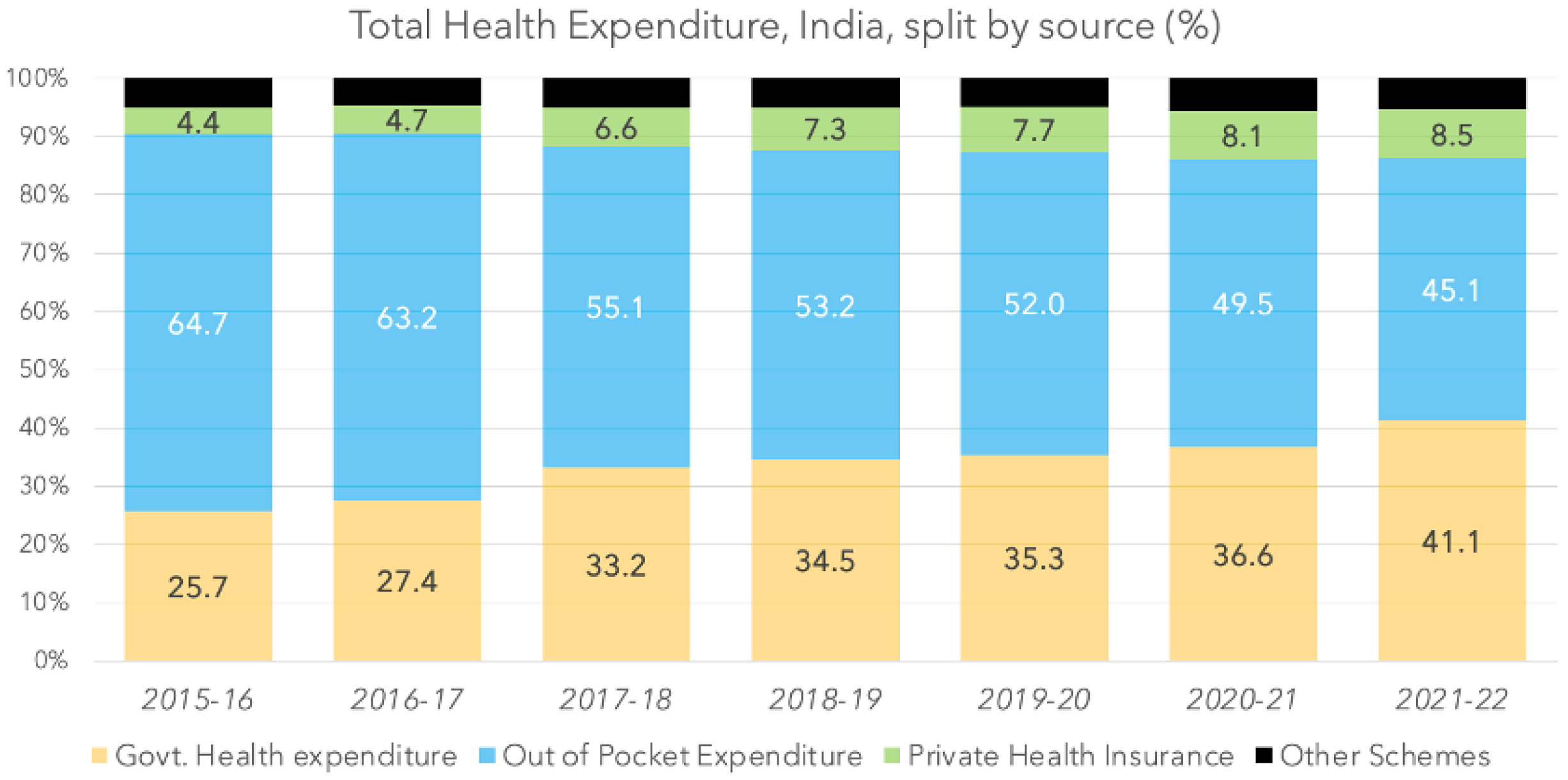

2.2. Aggregate Behavior of the Health-Insurance Sector in India

318 billion to

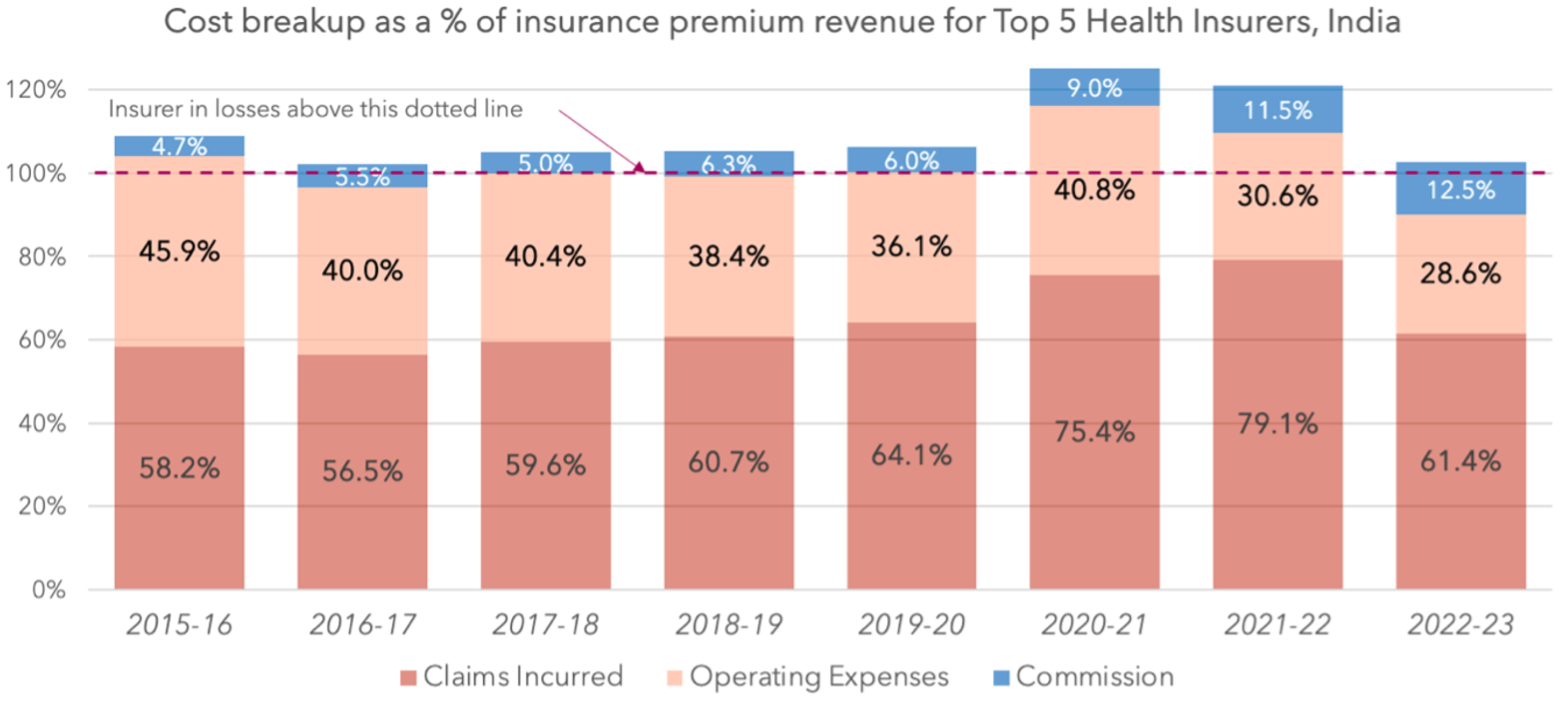

318 billion to  328 billion [15]. The situation is also similar for each of the five largest specialized health insurers (Table 2). It is also important to note that:

328 billion [15]. The situation is also similar for each of the five largest specialized health insurers (Table 2). It is also important to note that:- Retail (individual) commercial insurance covered 28.7 million lives in 2015–2016, a mere 2.3% of the total estimated population of 1.3 billion in 2016 [16], and grew at 9% per annum over the last seven years (Table 3), reaching covered lives of 52.9 mn by 2022–2023 [15]—covering 3.6% of the Indian population of 1.4 billion in 2023. Over this period, the retail insurance premium per covered life also grew at the rate of 9% per annum, with the average premium growing by 82% from a level of

3600 in 2015–2016 to

6600 in 2022–2023 (Table 3).

- For group insurance, the customer base grew from a level of 57 million covered lives in 2015–2016 [17] to 199 million in 2022–2023 [15]—a growth rate of almost 20% per annum, albeit on a low base (Table 4). However, the average premium per covered life barely changed from around

2000 to

2300, representing an annual growth rate of only 2% per annum (Table 4).

- The health-insurance industry in India has unusually high operating costs. This can be seen from the fact that, despite a limit of 35% for operating costs, a large number of insurers in India (17 of the 31 private insurers) are non-compliant and have operating costs over this limit [15]. In contrast, the Taiwanese single-payer health-insurance system has operating costs of under 2% [18]. In OECD countries, for social security schemes, the average administrative costs are about 4.2%. And while for private health-insurance plans, administrative costs are about three times higher [19], they are still significantly lower than those for India (Figure 2).

- As can be seen from Table 1, despite these high operating costs and adverse selection experience, there appears to have been no significant change in aggregate insurance premium per life over this period, even though retail health-insurance premiums (primarily in the private sector) have increased substantially each year (Table 3). This is because group insurance premiums (primarily offered by the public sector) have essentially remained unchanged over the last several years (Table 4). The Comptroller and Auditor General of India, in their recent review, remarked that the losses of the health-insurance business of PSU (public sector) insurers either wiped out/decreased the profits of other lines of business or increased the overall losses and, among other things, the cumulative losses of

263 billion for the last five years were incurred due to non-loading of premium for adverse claim experience [20].

| Year | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | 2021–2022 | 2022–2023 | 2015–2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRM |  0.22 tn 0.22 tn |  0.27 tn 0.27 tn |  0.33 tn 0.33 tn |  0.39 tn 0.39 tn |  0.46 tn 0.46 tn |  0.54 tn 0.54 tn |  0.67 tn 0.67 tn |  0.81 tn 0.81 tn | |

| Growth | 24.25% | 21.05% | 18.62% | 16.93% | 17.69% | 24.15% | 20.96% | 20% | |

| Lives | 0.09 bn | 0.10 bn | 0.12 bn | 0.12 bn | 0.14 bn | 0.17 bn | 0.21 bn | 0.25 bn | |

| Growth | 19.60% | 19.71% | −6.28% | 18.91% | 25.66% | 24.49% | 17.94% | 17% | |

| PPRM |  2564 2564 |  2664 2664 |  2693 2693 |  3409 3409 |  3352 3352 |  3140 3140 |  3131 3131 |  3211 3211 | |

| Growth | 3.88% | 1.12% | 26.56% | −1.66% | −6.34% | −0.27% | 2.56% | 3% | |

| Source | [17] | [17] | [17] | [17] | [21] | [22] | [23] | [15] | |

| Table, Pg | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.51, 58 | I.46, 53 | I.38, 36 | I.23, 40 | |

| THE |  5.28 tn 5.28 tn |  5.81 tn 5.81 tn |  5.67 tn 5.67 tn |  5.96 tn 5.96 tn |  6.56 tn 6.56 tn | ||||

| GHE |  1.62 tn 1.62 tn |  1.88 tn 1.88 tn |  2.31 tn 2.31 tn |  2.42 tn 2.42 tn |  2.72 tn 2.72 tn | ||||

| Source | [7] | [8] | [9] | [10] | [11] | ||||

| Pg | 5 | 5 | 27 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Ratio to THE | |||||||||

| PRM | 4.16% | 4.70% | 5.83% | 6.57% | 6.99% | ||||

| GHE | 30.63% | 32.36% | 40.78% | 40.61% | 41.41% | ||||

| TPE | 34.79% | 37.06% | 46.62% | 47.18% | 48.39% | ||||

bn) [24].

bn) [24].

bn) [24].

bn) [24].| Year | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | 2021–2022 | 2022–2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance Premiums () | 30.41 | 42.36 | 56.78 | 78.28 | 100.34 | 89.87 | 160.87 | 208.12 |

| Profit on Sale of Investments () | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 0.10 | 1.16 | 0.22 |

| Interest, Dividend & Rent () | 1.45 | 1.85 | 2.41 | 3.31 | 4.54 | 4.88 | 7.03 | 9.63 |

| Other Income - Other Expenses () | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 3.18 | 6.29 | 5.76 | 7.68 | 13.42 |

| Total Income () | 32.04 | 44.52 | 59.39 | 84.93 | 111.65 | 100.62 | 176.74 | 231.39 |

| Claims Incurred () | 17.70 | 23.92 | 33.83 | 47.50 | 64.35 | 67.79 | 127.19 | 127.87 |

| Commission () | 1.43 | 2.34 | 2.86 | 4.90 | 6.06 | 8.07 | 18.42 | 25.98 |

| Operating Expenses ( | 13.97 | 16.96 | 22.92 | 30.09 | 36.20 | 36.63 | 49.25 | 59.55 |

| Premium Deficiency () | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 1.11 | −1.36 | 0.00 |

| Total Expense () | 33.13 | 43.23 | 59.57 | 82.49 | 106.85 | 113.61 | 193.50 | 213.41 |

| Total Profit () | −1.09 | 1.28 | −0.18 | 2.44 | 4.80 | −12.99 | −16.76 | 17.98 |

| Underwriting Profits () | −2.72 | −0.87 | −2.79 | −4.22 | −6.51 | −23.74 | −32.63 | −5.29 |

| Investment Profits () | 1.63 | 2.15 | 2.61 | 6.66 | 11.31 | 10.75 | 15.87 | 23.27 |

| Year | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | 2021–2022 | 2022–2023 | 2015–2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRM |  0.10 tn 0.10 tn |  0.13 tn 0.13 tn |  0.15 tn 0.15 tn |  0.18 tn 0.18 tn |  0.20 tn 0.20 tn |  0.26 tn 0.26 tn |  0.30 tn 0.30 tn |  0.35 tn 0.35 tn | |

| Growth | 22% | 22% | 15% | 14% | 29% | 16% | 16% | 19% | |

| Lives | 0.03 bn | 0.03 bn | 0.03 bn | 0.04 bn | 0.04 bn | 0.05 | 0.05 bn | 0.05 bn | |

| Growth | 11% | 4% | 26% | 3% | 23% | −3% | 2% | 9% | |

| PPRM |  3607 3607 |  3933 3933 |  4592 4592 |  4163 4163 |  4617 4617 |  4863 4863 |  5828 5828 |  6573 6573 | |

| Growth | 9% | 17% | −9% | 11% | 5% | 20% | 13% | 9% | |

| Source | [17] | [17] | [17] | [17] | [21] | [22] | [23] | [15] | |

| Table, Pg | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.51, 58 | I.46, 53 | I.38, 36 | I.23, 40 |

| Year | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | 2021–2022 | 2022–2023 | 2015–2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRM |  0.12 tn 0.12 tn |  0.15 tn 0.15 tn |  0.18 tn 0.18 tn |  0.22 tn 0.22 tn |  0.26 tn 0.26 tn |  0.28 tn 0.28 tn |  0.37 tn 0.37 tn |  0.46 tn 0.46 tn | |

| Growth | 27% | 21% | 22% | 19% | 9% | 31% | 25% | 22% | |

| Lives | 0.06 bn | 0.07 bn | 0.09 bn | 0.07 bn | 0.09 bn | 0.12 bn | 0.16 bn | 0.20 bn | |

| Growth | 24% | 27% | −18% | 28% | 27% | 37% | 23% | 20% | |

| PPRM |  2039 2039 |  2088 2088 |  1986 1986 |  2973 2973 |  2768 2768 |  2368 2368 |  2273 2273 |  2319 2319 | |

| Growth | 2% | −5% | 50% | −7% | −14% | −4% | 2% | 2% | |

| Source | [17] | [17] | [17] | [17] | [21] | [22] | [23] | [15] | |

| Table, Pg | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.55–56, 48–49 | I.51, 58 | I.46, 53 | I.38, 36 | I.23, 40 |

2.3. Model Structure

2.3.1. Conceptual Model

2.3.2. Modeling Assumptions

- Only two health states are modeled (low-risk or healthy, high-risk or chronic), excluding short-term invalidation, acute illnesses, or temporary communicable diseases or conditions.

- We have births flowing directly into the healthy, low-risk population stock for simplicity and as a reasonable simplification for our consideration. We apply age-adjusted mortality rates across low- and high-risk populations, avoiding the structural complexity of explicit ageing chains. Births enter the healthy population at a rate of 1.5% of the total population per year, while deaths occur at an age-adjusted global average mortality rate [25], with a base mortality for ‘low-risk’ population at 0.7%, and with chronic (high-risk) mortality three times as high as that of the healthy population [26].

- The ‘low-risk’ or healthy insured population is derived from a stock of ‘low-risk fraction insured’, with flows governed by price sensitivity (elasticity) and adjusted yearly based on insurance price dynamics.

- Elasticity is treated as exogenous and defined as a step function, with higher elasticity when the insured fraction is low, and tapering off as coverage increases. This reflects saturation effects usually observed in the demand for insurance.

- The chronic insured population is modeled as an auxiliary, assuming 100% interest in insurance irrespective of price (i.e., the chronic population is price-inelastic). This allows the model to remain parsimonious while capturing the key dynamics.

2.3.3. Price Discovery Mechanism

- The premium floor is dynamically computed based on total claim costs and administrative costs from the previous period, with a 10% margin to ensure minimum viability. This price floor is disabled for group insurance.

- The premium ceiling is fixed at

20,000—8 times the initial quoted premium—to prevent unsustainable increases, growing at 1% each year to allow an inflationary margin.

- Within these bounds, the model uses a hill-climbing algorithm guided by total profits. If a change in premium in the previous period improved the total profit pool, the algorithm continues adjusting in that direction. If it reduced profits, the direction is reversed. The adjustment magnitude is fixed at a 1% margin per time step.

- Importantly, this mechanism interacts with insurance premium elasticity of the healthy population—higher premiums risk drop-offs in low-risk population enrollment, especially in the absence of managed care. This dynamic creates a feedback loop where premium increases can reduce the insured base of the low-risk population pool, in turn affecting future profits.

- The resulting quoted premium is a product of this feedback and is updated annually based on performance and population response from the previous period.

3. Stakeholders, Objectives and Strategies

3.1. Stakeholders and Objectives

3.1.1. Insurer

- (a)

- expanding insurance penetration to increase total revenue, although this is constrained by the price sensitivity of the healthy population;

- (b)

- limiting high-risk population from entering pool to reduce costs and boost profitability;

- (c)

- lowering the Claim Settlement Ratio, which controls post-insurance costs by managing the number of claims paid. This is used in two ways: (1) it is tightened when profits become negative due to higher claims, and (2) it accompanies risk-selection efforts by limiting claim payout when undisclosed chronic risk rises; and

- (d)

- increasing the insurance premium rapidly to account for higher claims, although this may reach a point where either the regulator steps in to restrict further increases or even the high-risk population stops buying insurance, or claims rise faster than the ability of the insurers to increase premiums.

3.1.2. Population

- The low-risk or healthy population shows relatively higher price sensitivity compared to the high-risk population and may drop out of the insured pool if premiums rise—a dynamic governed by price elasticity.

- The chronic population, facing higher medical costs, prioritizes maintaining coverage. Their primary concern is avoiding exclusion from insurance due to risk selection, and they may withhold health information to bypass restrictions.

3.1.3. Regulator

3.2. Strategies and Stakeholder Interactions

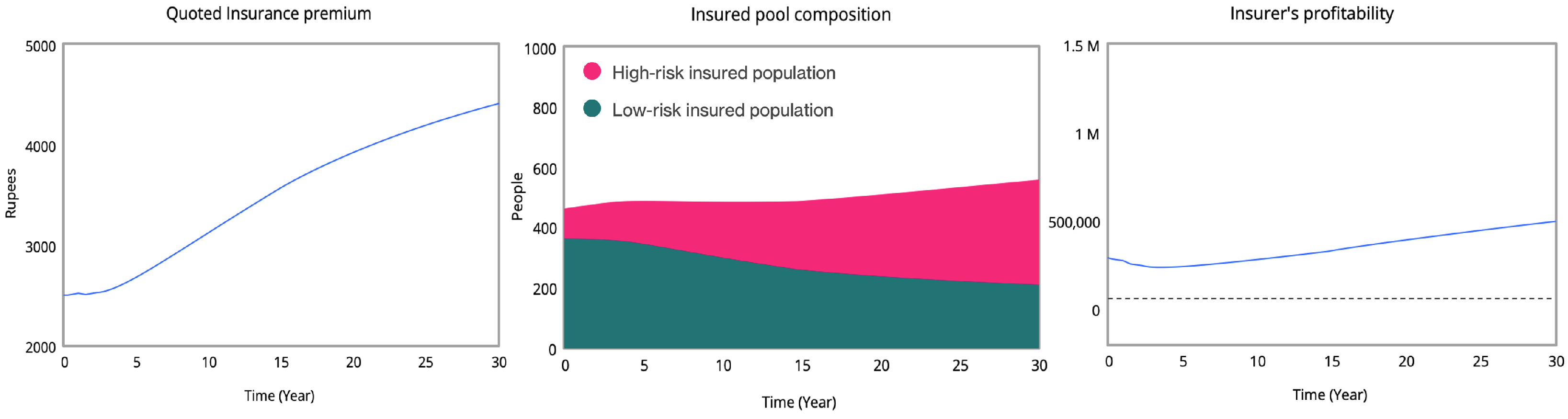

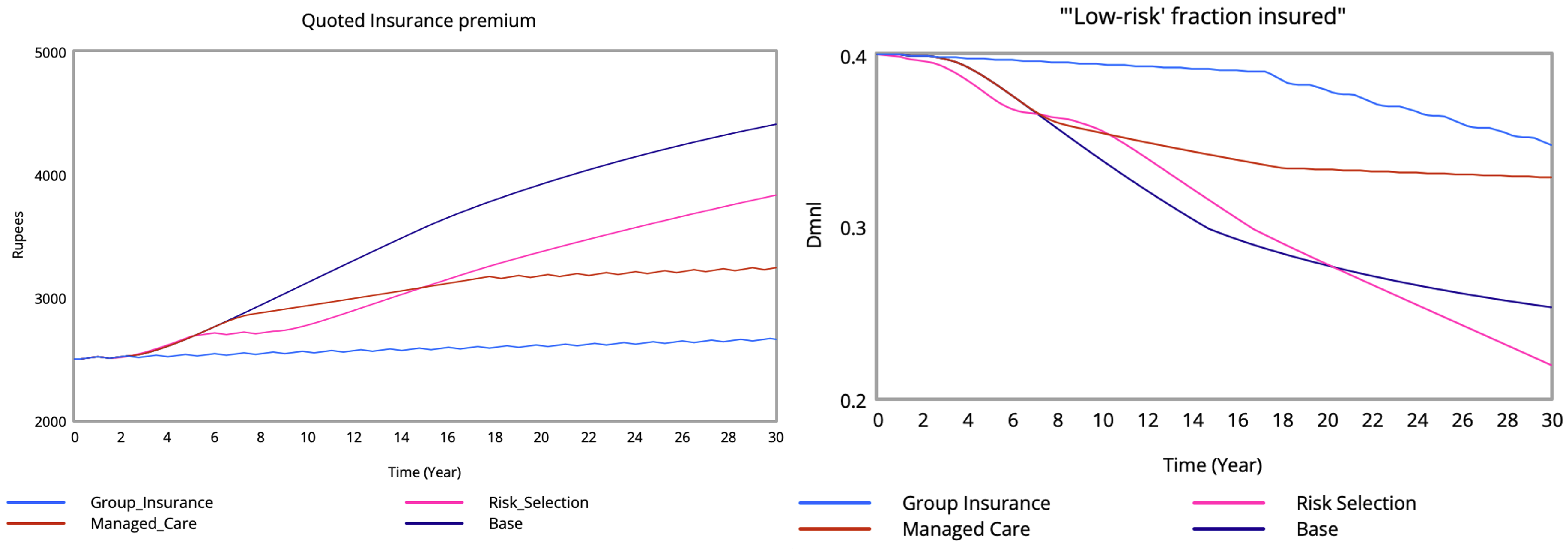

3.2.1. Base Scenario

- 1.

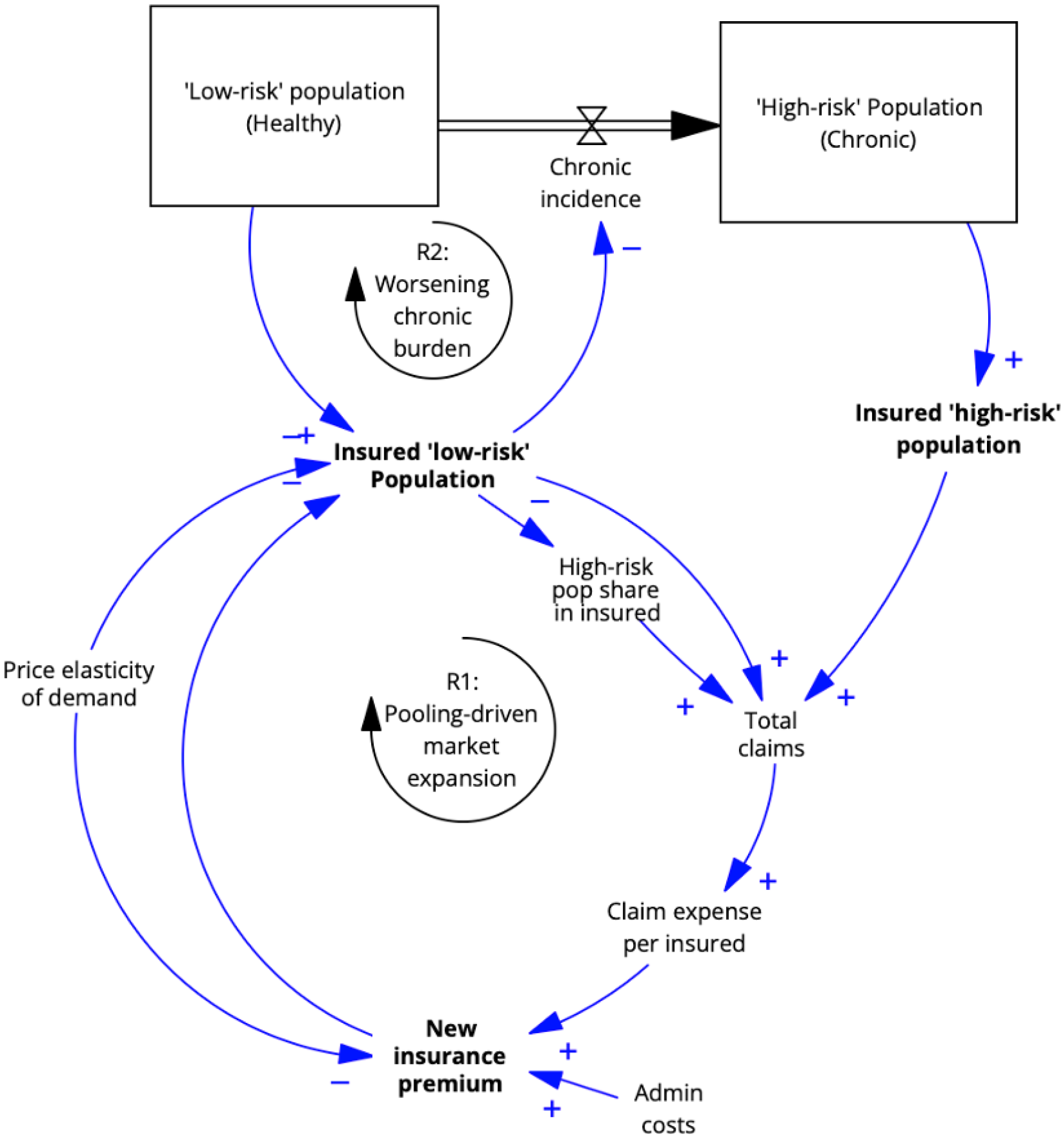

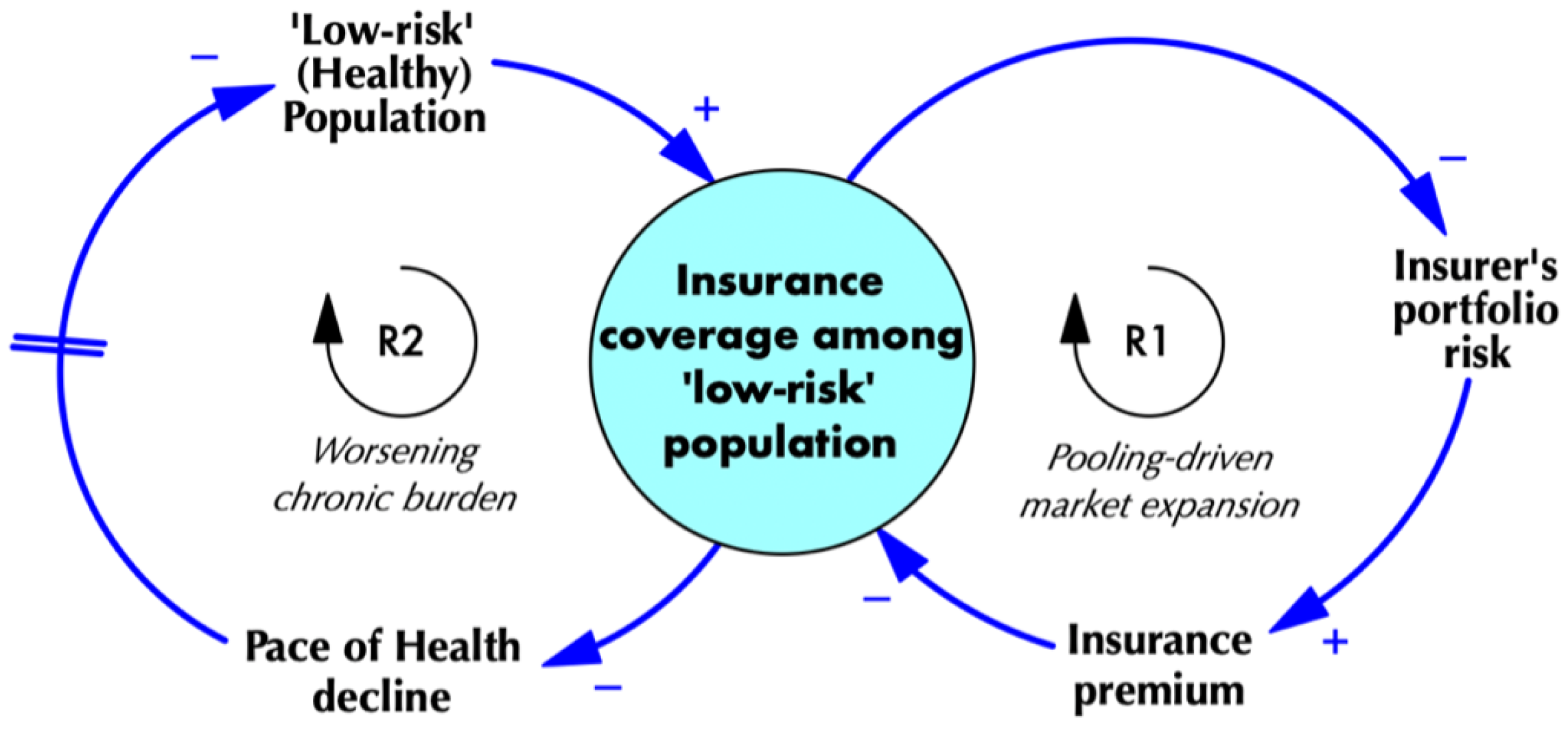

- Insurance Market expansion (or contraction) [R1]: This reinforcing loop (Figure 5) demonstrates how the initial size of the low-risk (healthy) insured pool influences premiums. When more healthy individuals are insured, the insurer can spread risk more effectively, keeping premiums lower, which in turn attracts or retains more healthy individuals in the pool. However, if fewer low-risk, non-chronic individuals are insured initially, the insurer’s portfolio risk increases, driving up premiums. This leads to even more healthy individuals leaving the insured pool due to their higher elasticity.

- 2.

- Population’s chronic burden [R2]: This reinforcing loop (Figure 5) focuses on the overall health of the population. When insurance penetration among the low-risk, non-chronic population is low, fewer individuals access timely care or diagnosis. This accelerates health deterioration, pushing more people into chronic conditions and shrinking both the overall and the insured share of the low-risk, non-chronic population.

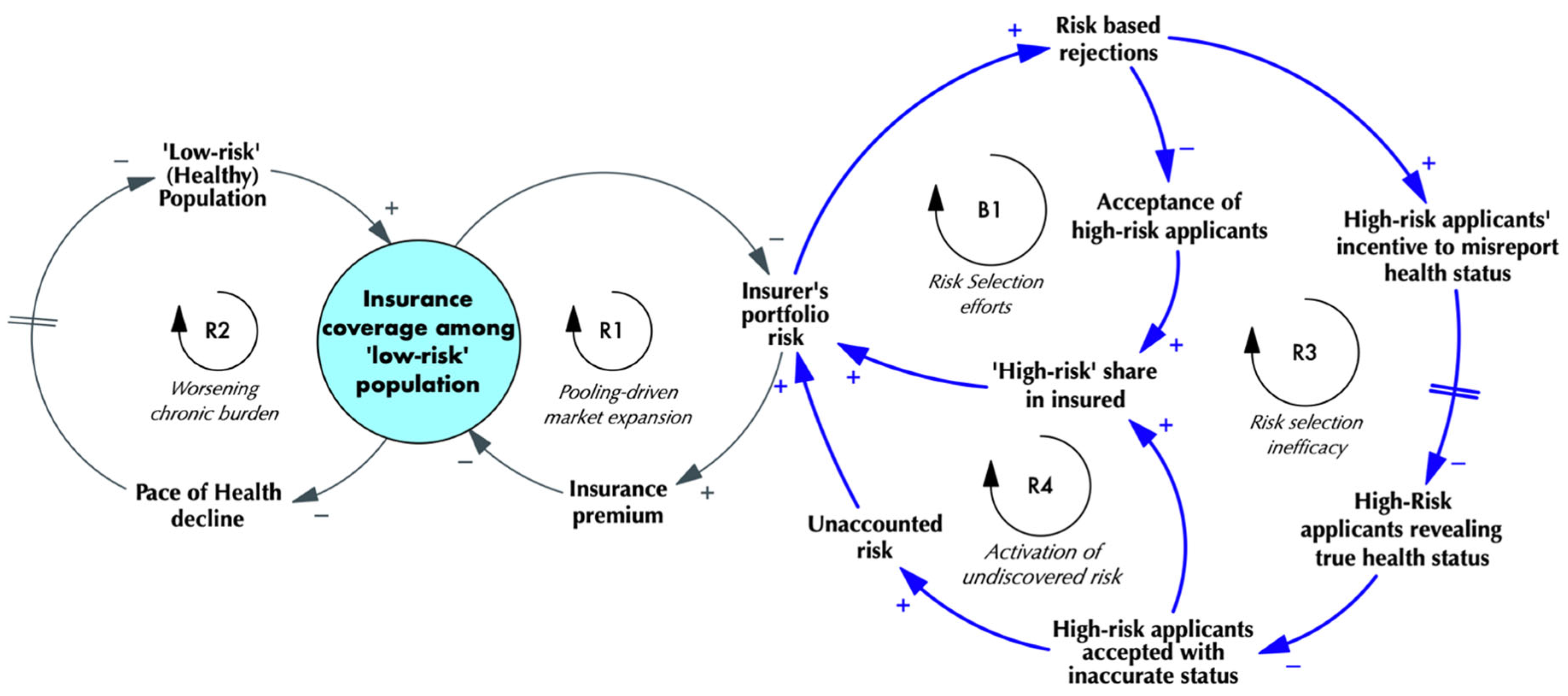

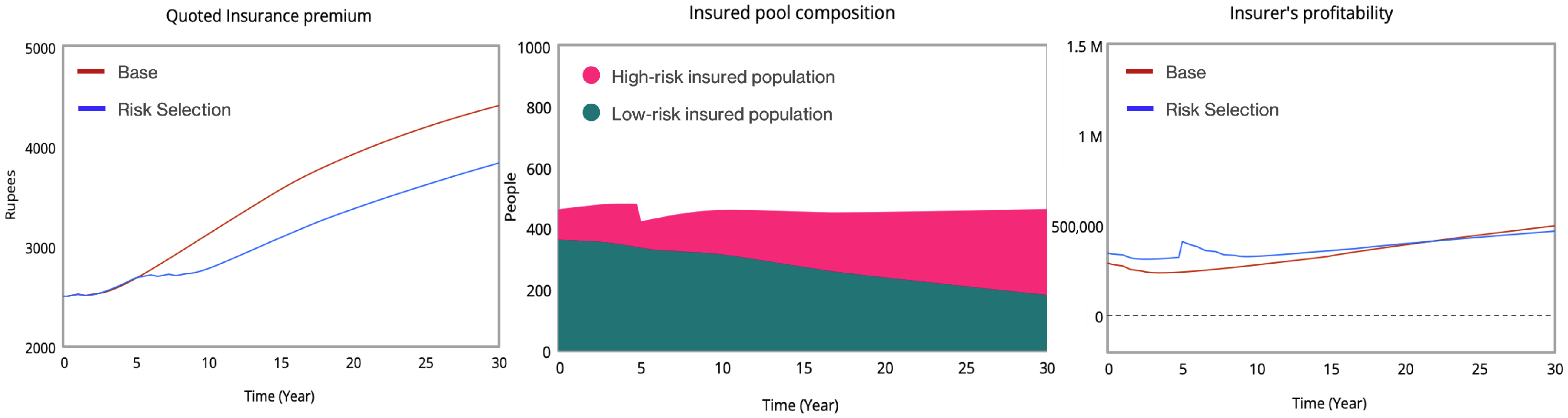

3.2.2. Risk Selection

- 3.

- Risk Selection Efforts [B1]: Insurers aim to reduce claims costs by rejecting individuals with chronic conditions. By focusing on low-risk populations, insurers attempt to lower their portfolio risk. They expect to reduce the share of the higher-risk population with chronic conditions in their portfolios to balance the risk.

- 4.

- Risk-selection inefficacy [R3]: In response to insurers’ risk-selection efforts, high-risk or chronically ill applicants, who have a stronger incentive to obtain coverage, often attempt to bypass this rejection process by concealing their true health status once they learn about this risk-selection process. Because insurers lack independent access to medical information beyond what is voluntarily disclosed, many high-risk individuals are accepted into the pool under misrepresented health conditions.

- 5.

- Activation of undiscovered risk [R4]: By concealing health risks, chronic patients enter the insurance pool while insurers underwrite the risk based on declared health status. This introduces an element of unaccounted risk into the underwritten pool, which further increases the portfolio risk of the insurer, as it has even less visibility than before into the expected volume and value of claims generated by the insured pool.

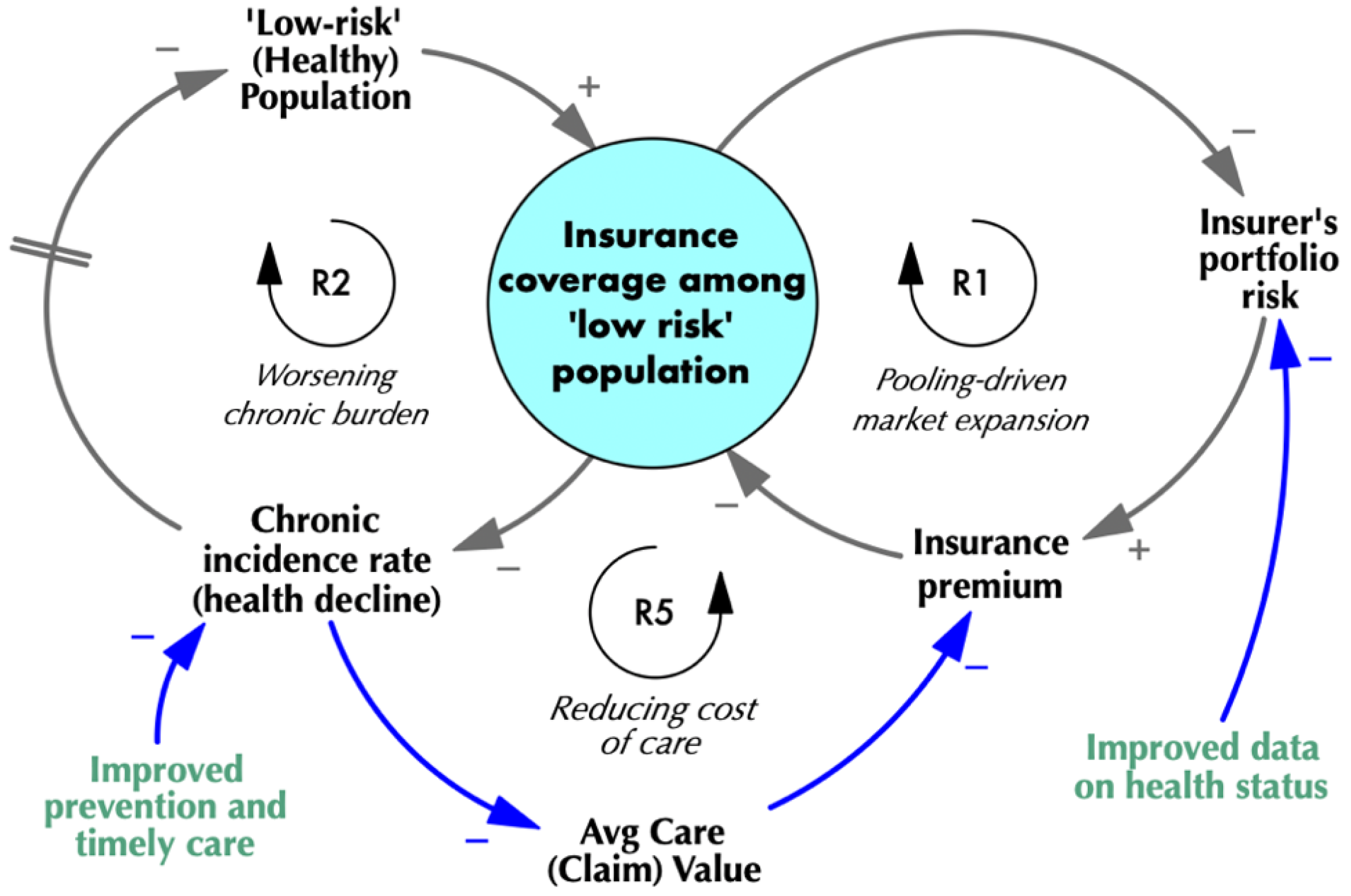

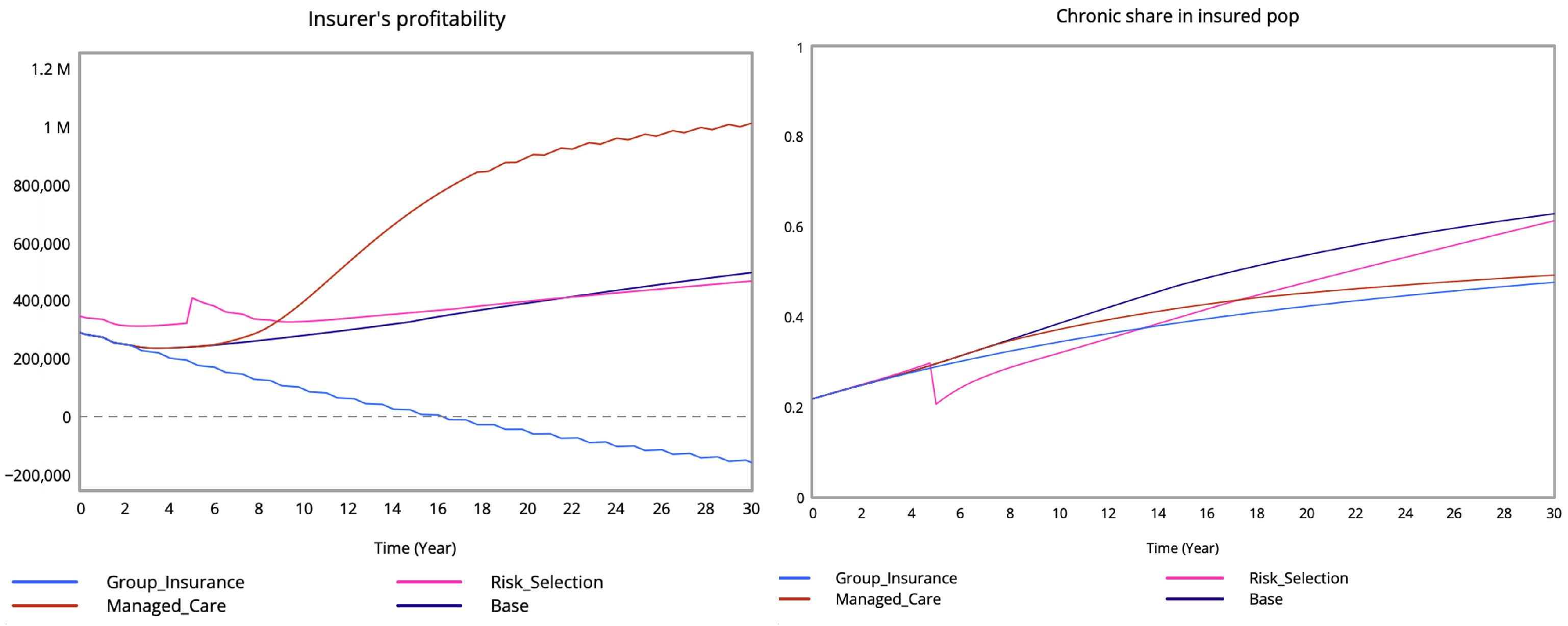

3.2.3. Managed Care

- 6.

- Reducing cost of care [R5]: The managed-care model reduces the incidence of chronic conditions over time by reducing the delay in care-seeking through improved primary care and preventive services. It also improves the attractiveness of the insurance product for low-risk and healthy buyers, due to its value-added offering, further attracting the low-risk population into the insured pool. The reduced chronic incidence for the insured pool allows the average cost of care to decline over time (due to reduced frequency and value of claims), although these benefits typically emerge after a lag of 7–8 years.

4. Results

4.1. Base Case

4.2. Universal-Coverage Scenario (Benchmark)

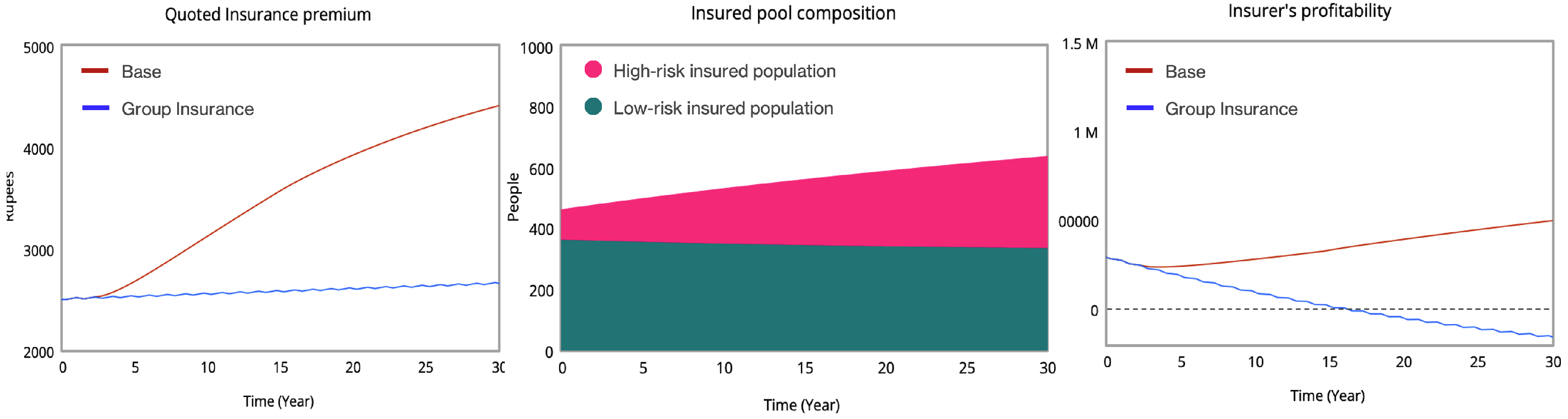

4.3. Group Insurance (Insurer as Price Taker)

4.4. Risk Selection (Introduced in Year 5)

4.5. Managed Care (Introduced in Year 5)

5. Additional Analyses

6. Discussion

6.1. Insurer

6.2. Population

Regulator

6.3. Recommendation

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Model Documentation

Appendix A.1. Model Equations

| Variable/Equation | Units | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ‘High-risk’ applicant fraction rejected by insurer | Dmnl [0, 1] | The fraction of chronic status applicants rejected by the insurance company as part of its risk-selection strategy. |

| ‘High-risk’ applicants concealing health status | 1 | Percentage of ‘chronic status’ applicants able to circumvent risk-based rejections. |

| ‘High-risk’ fraction SEEKING INSURANCE | Dmnl [0, 1] | Fraction of chronic status population seeking insurance. |

| ‘High-risk’ pop insured | People | Total number of chronic status people with insurance. |

| ‘High-risk’ Population (Chronic) | People | Total population with chronic ailments. |

| ‘Low-risk’ buyers dissatisfied by low claim settlement | undefined | |

| ‘Low-risk’ fraction insured initial | Dmnl | |

| ‘Low-risk’ fraction insured | Dmnl [0, 1] | Fraction of healthy population with health insurance. |

| ‘Low-risk’ pop insured | People | |

| ‘Low-risk’ Population (Healthy) | People | Total healthy or low-risk population. |

| Admin cost | undefined | Risk-selection policy increases admin cost to 25% of claim cost from 15%. |

| Age-adjusted base mortality rate | Dmnl | Mortality rate for the healthy population. |

| Avg age of population | Dmnl | |

| Avg claim | Rupees/People | |

| Base chronic incidence | Dmnl [0, 1] | % of the population becoming chronically ill every year. |

| Births per yr | undefined | |

| Change in ‘low-risk’ frac insured | undefined | |

| Change in premium | Rupees/Year | |

| Chronic incidence in period | People/Year | People who have chronic concerns during the period. |

| Chronic incidence rate | Dmnl [0, 1] | Rate of chronic incidence for the healthy population every year. |

| Chronic incidence x claim multiplier | Dmnl [0, 15] | |

| Chronic mortality rate | undefined | |

| Chronic share in insured pop | Dmnl | |

| Chronics’ Truth ratio | Dmnl [0, 1] | Percentage of ‘chronic status’ applicants misrepresented as ‘healthy status’. |

| Claim cost per insured | Rupees/People | |

| Claim settlement ratio | Dmnl [0, 1] | |

| Claims from chronic pop | Rupees | |

| Claims from low-risk pop | Rupees | |

| Claims settled | Rupees | |

| Deaths of High-Risk pop per yr | People/Year | |

| Deaths of low-risk pop per yr | People/Year | |

| Group insurance switch (insurer is price taker) | undefined [0, 1, 1] | |

| Healthy share initial | Dmnl | Fraction of the total population that is healthy at the start. |

| Initial population | undefined | Total population in the system. |

| Initial premium | undefined | |

| Insurer profitability trend | undefined | |

| Insurer Revenue | Rupees | Total revenue earned by the insurance company. |

| Insurer’s profitability | undefined | |

| Intervention Time Step | undefined | The year in which policy decisions are rolled out. |

| Last year’s insurance premium | Rupees/Year | |

| Last year’s profitability | undefined | |

| Life expectancy | Year | |

| Managed-care effect | undefined | |

| Managed-care incidence reduction | Dmnl [0, 1, 0.05] | % by which chronic incidence reduces as a result of managed care. |

| Managed-care switch | Dmnl [0, 1, 1] | Toggles Managed Care (1 = On, 0 = Off). |

| Margin of change | undefined | |

| MC effect time delay | undefined [4, 15, 1] | Years for managed care to reduce chronic incidence rates. |

| Minimum viable margin | undefined | |

| Premium ceiling | undefined | |

| Premium change percentage | Dmnl | |

| Premium direction | undefined | |

| Premium floor | Rupees/People | Minimum premium charged to cover costs and margin. |

| Price elasticity for ‘low-risk’ pop | undefined | Demand sensitivity for insurance by the healthy population. |

| Profit motivated premium | undefined | |

| Quoted Insurance premium | Rupees | Premium quoted by the company. |

| Risk Rejection fraction | Dmnl | % of ‘chronic status’ applicants sharing true status that are rejected. |

| Risk-selection effect | Dmnl | Activates risk selection unless managed care is on. |

| Risk-selection switch | Dmnl [0, 1, 1] | Toggles Risk Selection (1 = On, 0 = Off). |

| Total Insured | People | Total covered people. |

| Total pop | People | Total Population. |

| Viable Premium direction | undefined |

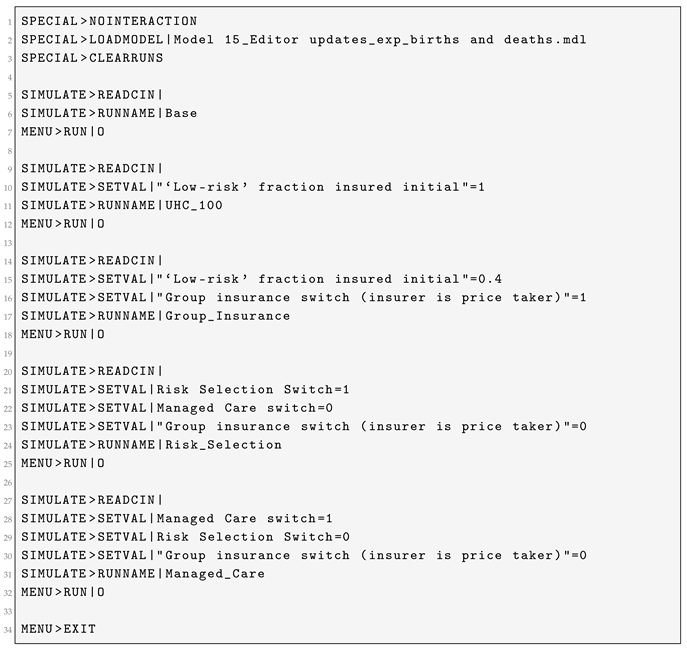

Appendix A.2. Scenario Setup

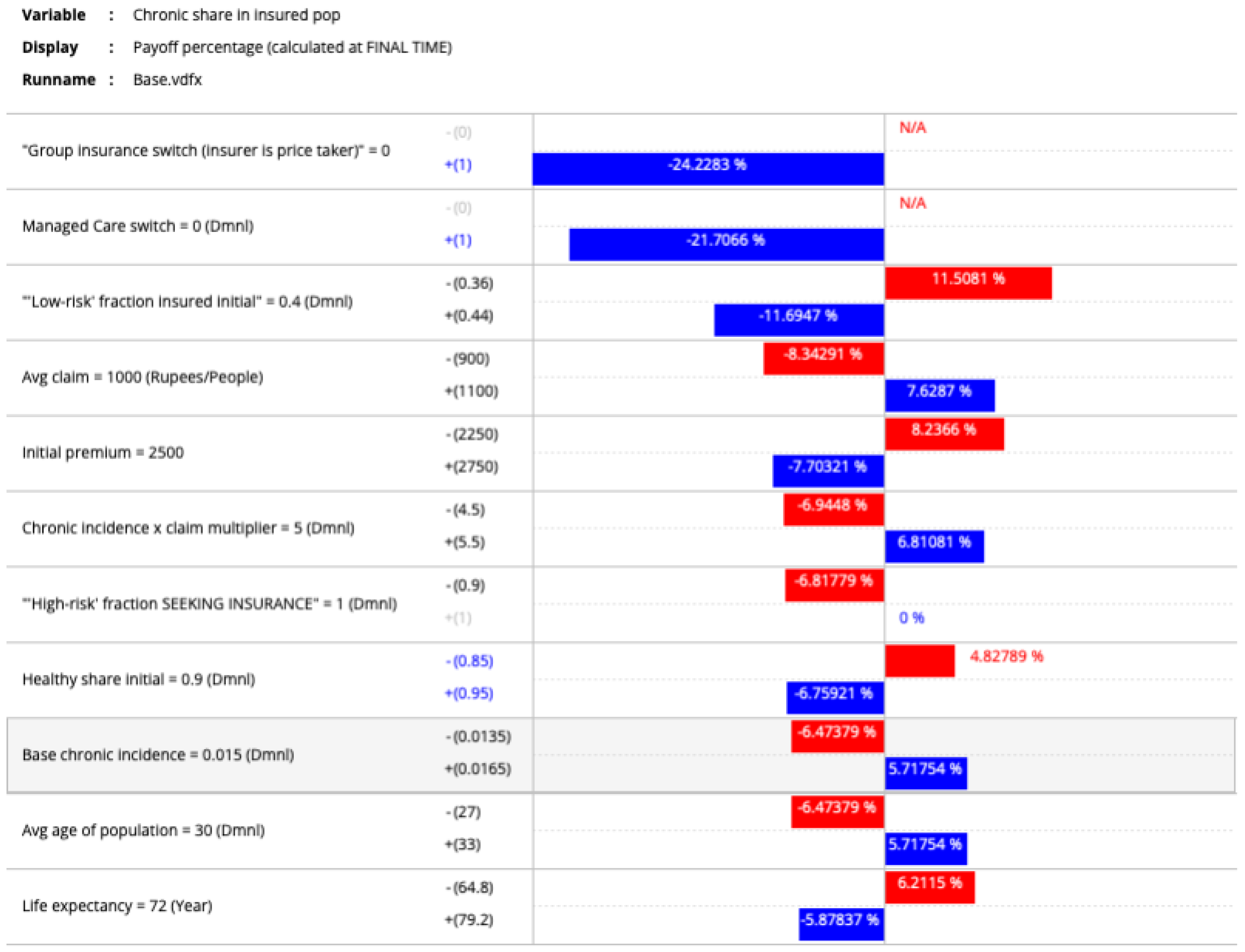

Appendix B. Sensitivity Analysis Results

Appendix B.1. Sensitivity of Various Outcomes of Interest

Appendix B.1.1. Insurance Premium

Appendix B.1.2. Low-Risk (Healthy) Population

Appendix B.1.3. Insurer Profitability

Appendix B.1.4. Low-Risk Fraction Insured

Appendix B.1.5. Chronic Share in Insured

References

- Roberts, M.J.; Hsiao, W.; Berman, P.; Reich, M.R. Getting Health Reform Right: A Guide to Improving Performance and Equity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mor, N. Lessons for Developing Countries From Outlier Country Health Systems. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 870210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazbeck, A.S.; Soucat, A.L.; Tandon, A.; Cashin, C.; Kutzin, J.; Watson, J.; Thomson, S.; Nguyen, S.N.; Evetovits, T. Addiction to a bad idea, especially in low- and middle-income countries: Contributory health insurance. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 320, 115168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mor, N.; Ashraf, H. Is contributory health insurance indeed an addiction to a bad idea? A comment on its relevance for low- and middle-income countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 320, 115918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHSRC. Household Health Expenditures in India (2013–14); Technical Report; National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC): New Delhi, India, 2016; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- NHSRC. National Health Accounts: Estimates for India 2014–15; Technical Report; National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC): New Delhi, India, 2017; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- NHSRC. National Health Accounts Estimates for India (2015–16); Technical Report; National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC): New Delhi, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- NHSRC. National Health Accounts Estimates for India (2016–17); Technical Report; National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC): New Delhi, India, 2019; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- NHSRC. National Health Accounts Estimates for India (2017–18); Technical Report; National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC): New Delhi, India, 2021; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- NHSRC. National Health Accounts Estimates for India (2018–19); Technical Report; National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC): New Delhi, India, 2022; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- NHSRC. National Health Accounts Estimates for India 2019–20; Technical Report; National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC): New Delhi, India, 2023; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Foubister, T.; Richardson, E. United Kingdom. In Voluntary Health Insurance in Europe: Country Experience; Sagan, A., Thomson, S., Eds.; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; Chapter 34. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, W.C. Why is a Systemic View of Health Financing Necessary? Health Aff. 2007, 26, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darabi, N.; Hosseinichimeh, N. System dynamics modeling in health and medicine: A systematic literature review. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2020, 36, 29–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRDAI. Annual Report 2022–2023; Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI): Mumbai, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- MoHFW. Population Projections for India and States 2011–2036; Technical Report; Technical Group on Population Projections, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare: New Delhi, India, 2020; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- IRDAI. IRDAI Annual Report 2018–19; Technical Report; Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI): Hyderabad, India, 2019; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.Y.; Majeed, A.; Kuo, K.N. An overview of the healthcare system in Taiwan. Lond. J. Prim. Care 2010, 3, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathauer, I.; Nicolle, E. A global overview of health insurance administrative costs: What are the reasons for variations found? Health Policy 2011, 102, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CAG. Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Compliance Audit of Third Party Administrators in Health Insurance business of Public Sector Insurance Companies Union Government (Commercial) Ministry of Finance (Department of Financial Services); Technical Report; Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG): New Delhi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IRDAI. Annual Report 2019–20; Technical Report; Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI): Hyderabad, India, 2020; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- IRDAI. IRDAI Annual Report 2020–21; Technical Report; Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI): Hyderabad, India, 2021; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- IRDAI. Annual Report 2021–22; Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI): Hyderabad, India, 2021; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- IRDAI. Handbook on Indian Insurance Statistics 2022–2023; Technical Report; Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI): Hyderabad, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Crude Death Rate (per 1000 People). World Development Indicators. 2025. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.CDRT.IN (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Ven, W.V.; Hamstra, G.; Kleef, R.v.; Reuser, M.; Stam, P. The goal of risk equalization in regulated competitive health insurance markets. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2023, 24, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mor, N.; Gupta, A.; Roy, R. Reimagining Commercial Health Insurance in India: A System-Dynamics Approach to Complex Stakeholder Incentives and Policy Outcomes. Systems 2025, 13, 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121104

Mor N, Gupta A, Roy R. Reimagining Commercial Health Insurance in India: A System-Dynamics Approach to Complex Stakeholder Incentives and Policy Outcomes. Systems. 2025; 13(12):1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121104

Chicago/Turabian StyleMor, Nachiket, Aakriti Gupta, and Rahul Roy. 2025. "Reimagining Commercial Health Insurance in India: A System-Dynamics Approach to Complex Stakeholder Incentives and Policy Outcomes" Systems 13, no. 12: 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121104

APA StyleMor, N., Gupta, A., & Roy, R. (2025). Reimagining Commercial Health Insurance in India: A System-Dynamics Approach to Complex Stakeholder Incentives and Policy Outcomes. Systems, 13(12), 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121104