Abstract

This paper investigates how geopolitical risk influences firm profitability worldwide. Using a global panel of 7126 listed companies from 2013 to 2023, the analysis reveals that geopolitical shocks do not affect firms uniformly. Less profitable and financially fragile firms experience the strongest declines in profitability when geopolitical tensions rise, while more profitable firms show greater resilience and, in some cases, strategic gains. The results also indicate that financial structure, liquidity, tangibility, and innovation capacity explain much of this heterogeneity, highlighting that vulnerability is rooted in both balance sheet fragility and adaptive capability. These findings suggest that geopolitical instability reinforces performance asymmetries across firms and industries, with implications for corporate strategy, investor behavior, and financial stability in an increasingly uncertain global environment.

1. Introduction

A big part of the world economy is now geopolitically unstable. The annexation of Crimea, the trade tensions between the US and China, and the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 show how political events reshape production networks, supply chains, energy markets, and financial systems. Shocks were once viewed mainly in macroeconomic terms, but it is now evident that geopolitical disruptions directly affect firms by influencing sales, profitability, and operational stability. Company performance therefore depends not only on internal efficiency and market conditions but also on the broader political environment and global fragmentation.

Businesses are exposed to geopolitical shocks through multiple, interconnected channels. Tariffs, sanctions, supply chain disruptions, and energy price volatility are direct transmission mechanisms, while financial contagion, commodity market swings, and shifts in international demand represent indirect ones. These factors increase cash-flow volatility and the risk of financial distress, particularly for firms with weak profitability or fragile balance sheets. In contrast, more profitable firms can rely on financial buffers and strategic flexibility to absorb or even exploit periods of uncertainty. According to trade-off theory, the cost of financial distress rises under uncertainty, while real options theory suggests that risk delays investment and limits growth opportunities.

Empirical evidence supports these mechanisms. The geopolitical risk index in ref. [1] is now a standard measure of global shocks. Ref. [2] shows that firms reduce investment under increased geopolitical risk, while ref. [3] finds that tensions raise the cost of equity and constrain financing in emerging markets. Ref. [4] documents that geopolitical risk reduces firm value, particularly through local shocks, and ref. [5] shows that even small changes in risk perception can alter investor flows, emphasizing the importance of behavioral channels. Managerial dimensions also matter, as ref. [6] demonstrates that executive characteristics influence how firms adjust capital structure decisions under uncertainty. Sectoral studies confirm heterogeneity, with ref. [7] showing that operating leverage affects profitability.

This literature indicates that geopolitical risk is a key determinant of firm outcomes, though its effects are highly uneven. Firms with low profitability, limited liquidity, and higher exposure to financial distress are hit hardest when geopolitical shocks increase cash-flow volatility and borrowing costs. More profitable firms can better manage uncertainty and sometimes transform volatility into opportunity. This adaptive capacity creates a competitive advantage during crises, mirroring the “flight-to-quality” phenomenon in financial markets, where capital and customers gravitate toward stronger and more resilient firms.

This paper provides a comprehensive global analysis of how geopolitical risk influences corporate profitability, using a panel of 7126 publicly traded companies from 2013 to 2023. Combining firm-level analysis with unconditional quantile regression and machine learning methods, the study identifies heterogeneity across the profitability distribution and the firm characteristics that shape vulnerability to geopolitical shocks. These findings have significant implications for corporate finance and economic policy. They show that the interaction between firm structure and geopolitical risk critically shapes profitability, revealing that financial fragility and adaptive capacity determine how firms respond to global uncertainty. For managers, the results emphasize the need to build financial resilience through prudent leverage, liquidity buffers, and strategic diversification of markets and supply chains. Strengthening these dimensions can mitigate earnings volatility and sustain profitability during periods of geopolitical stress. For investors, the evidence suggests that geopolitical risk should be incorporated into asset valuation and portfolio allocation, as firms with weak financial positions command higher risk premia and greater return volatility. For policymakers, the asymmetric impact of geopolitical shocks implies that smaller and financially constrained firms warrant closer monitoring, since their vulnerability can magnify systemic instability. Targeted credit support and crisis-contingent instruments can help contain these effects and preserve economic stability when global tensions rise.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature. Section 3 presents the data and methodology. Section 4 discusses the empirical results and robustness checks, including causality analysis. Section 5 discusses the findings, with implications for corporate strategy and policy, while Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Hypothesis Development

The list of articles was extracted from the Web of Science Core Collection using a topic-based search focused on identifying the determinants of firm profitability. The query included the phrase “determinants of firm profitability” in the Topic field and was refined by adding relevant methodological and contextual keywords such as panel data. To ensure the relevance and contemporaneity of the literature, the search was restricted to articles published between 2020 and 2024 and indexed in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) under the categories Economics or Business Finance. Only research articles were retained, excluding reviews and conference proceedings. Applying these criteria resulted in a final sample of 34 articles that empirically examine the determinants of firm profitability.

The literature emphasizes that firm scale and market intensity are central determinants of performance because larger firms reduce average costs, improve bargaining power and have easier access to external finance. In the insurance and banking sectors, size is systematically associated with higher profitability after controlling for risk (see ref. [8]). During crisis episodes, firm size also matters for financing conditions as larger firms benefit from lower costs of debt, which in turn improves margins when funding is tight (see ref. [9]). Sales and market reach further reinforce profitability since they interact with cost structures, as shown in European SMEs where operating leverage amplifies the impact of size and indebtedness on performance (see ref. [10]). These findings justify the inclusion of size and sales as key variables in any profitability model.

Capital structure and leverage are repeatedly highlighted as important determinants of profitability through both the tax shield and distress costs. Empirical evidence shows nonlinear effects in the case of working capital and trade credit, where profitability rises with leverage up to a point and declines beyond the optimum (see ref. [11]). Zero leverage strategies improve profitability only for unconstrained firms, particularly in crises, while constrained firms see no benefit (see ref. [12]). Crisis time studies also demonstrate that leverage lowers cost of debt for large transparent issuers but worsens financing costs for illiquid firms (see ref. [9]). Taken together, these findings underline the importance of leverage in explaining profitability outcomes.

Collateral and asset tangibility reinforce the profitability–financing nexus by enhancing pledgeability and reducing agency conflicts. Evidence from intragroup financing in Spain shows that tangibility is a positive determinant of internal debt, but intragroup borrowing is negatively related to profitability and crowds out external borrowing, consistent with pecking order behavior (see ref. [13]). Research on the tax shield in Central and Eastern Europe further identifies tangibility as a main driver of debt incentives (see ref. [14]). Studies on operating leverage also show that cost structure tied to fixed assets shapes how innovation and reputation translate into profits (see ref. [10]). These results support the use of tangibility as an explanatory factor of profitability.

The relationship between banks and firms provides another important channel. Firms with multiple bank relationships tend to be more leveraged, while higher banking concentration reduces leverage, a phenomenon described as the mainstream bank curse (see ref. [15]). Evidence also indicates that bank market power raises fintech profitability but not that of non-fintech firms (see ref. [16]). Studies on corporate governance find that CEO duality affects trade credit policies, thereby influencing sales and profitability (see ref. [17]). Such results justify the use of variables that capture the role of financial intermediaries, such as having a bank as advisor, to proxy for lower frictions and better access to finance.

Managerial attributes and governance structures are shown to affect profitability through their impact on strategic choices and risk attitudes. In Nigerian banks, the relation between CEO pay and firm performance varies significantly across institutions, depending on interdependence and firm-specific strategies (see ref. [18]). Evidence also suggests that CEO duality affects trade credit management in ways that can increase profitability despite higher operational risk (see ref. [17]). Other research links leadership and governance choices to acquisition strategies and performance in specialized sectors (see ref. [19]). In this context, CEO gender represents a relevant proxy for leadership diversity and its potential implications for profitability.

Finally, macroeconomic conditions and uncertainty are powerful determinants of profitability. In financial services, GDP growth and market dynamics are significant drivers of firm performance (see ref. [8]). In Poland, weaker property rights, lower growth and higher volatility are shown to reduce profits and investment capacity (see ref. [20]). In BRIC countries, economic policy uncertainty has both immediate and lagged negative effects on profitability, transmitted through capital structure and institutional quality (see ref. [21]). Energy shocks and crises also demonstrate that macro disruptions pass through to firm margins by altering costs and demand (see ref. [22]). These consistent findings on the damaging role of uncertainty lead us to hypothesize that geopolitical risk, as a salient form of external uncertainty, negatively affects firm profitability.

Building on the evidence that macroeconomic volatility and policy uncertainty systematically weaken firm performance, geopolitical risk can be interpreted as an external shock that amplifies these dynamics through both financial and operational channels. Heightened geopolitical tensions raise financing costs, increase cash flow volatility, and disrupt trade networks and investment plans, all of which constrain firms’ ability to sustain profitability. Firms exposed to greater geopolitical risk are therefore expected to experience lower returns on assets and reduced profit margins, particularly when leverage and liquidity buffers are limited. Accordingly, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H1.

Geopolitical risk exerts a negative and statistically significant effect on firm profitability.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Data Description

In this paper, we rely on a balanced panel with yearly data, from 2013 to 2023, using a sample of 7126 firms worldwide. We selected from the ORBIS database only those listed companies that reported complete financial information for the entire period under analysis and that are headquartered in countries for which the geopolitical risk index is available.

The sectoral composition of the sample confirms a strong concentration in capital-intensive industries, with Industrial, Electric & Electronic Machinery accounting for the largest share (18.93%), followed by Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic (11.20%) and Metals & Metal Products (5.99%). Other sizable contributions come from Business Services (5.63%), Wholesale (5.22%), and Property Services (5.05%), indicating a balanced mix between industrial activity and service-oriented firms. Consumer-focused sectors such as Food & Tobacco Manufacturing (4.53%), Construction (4.04%), Retail (3.49%), and Transport & Logistics (around 3–3.6% each) are also well represented, reflecting the breadth of listed firms across different parts of the value chain. In contrast, knowledge- and innovation-intensive sectors remain relatively modest, with Computer Software (2.60%), Computer Hardware (1.96%), and Biotechnology and Life Sciences (0.22%) capturing only small fractions of the sample. The least represented activities include Waste Management & Treatment (0.14%) and Public Administration, Education, Health & Social Services (0.86%), consistent with their limited stock market presence. Notably, fintech and digital finance firms do not appear as a separate category, largely due to data gaps and classification inconsistencies that prevent the construction of a structured panel. Overall, the sample remains skewed toward globally integrated, capital-heavy sectors, which are most exposed to geopolitical risk, an aspect that reinforces the interpretation of the empirical analysis.

At the country level, the sample is heavily concentrated in Asia, with Japan (27.66%), region Taiwan (12.99%), and China (11.59%), together accounting for over half of all firms. At the opposite end, representation is minimal for Tunisia (0.06%), Portugal (0.15%), and Peru (0.20%), reflecting both structural differences in capital markets and the limited availability of firm-level panel data in these jurisdictions.

A detailed description of all the variables we employ in the regression analysis is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the variables.

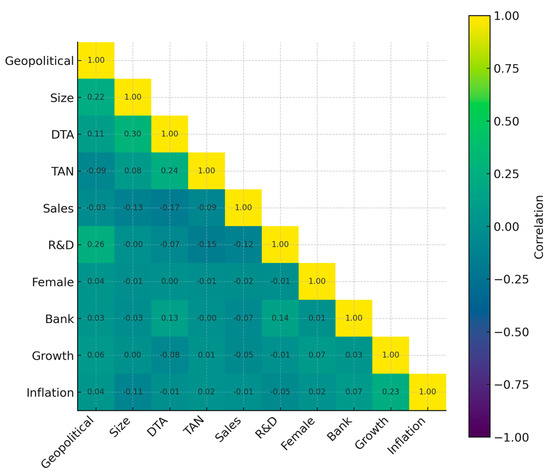

We now proceed to address potential multicollinearity issues within the dataset. Presenting the correlation matrix of the explanatory variables is a critical step, as it provides initial insights into the strength and direction of the linear relationships between covariates. Detecting high pairwise correlations is essential to ensure that the estimated coefficients are stable and interpretable, and that the explanatory power of each variable is not artificially inflated by overlapping information. Figure 1 displays the lower triangular correlation matrix, including the diagonal, which highlights moderate associations between some financial indicators, while also reassuring us that no excessively strong correlations are present that would threaten the reliability of the regression analysis. This diagnostic step enhances the robustness of the econometric specification and supports the credibility of subsequent inferences about the drivers of profitability.

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix. Source: Own processing.

Multicollinearity typically becomes a concern when correlations between explanatory variables are very strong, generally exceeding 0.80 or 0.90. Although the matrix reveals some statistically significant associations, the observed correlation coefficients remain at moderate levels and do not suggest the presence of severe multicollinearity. However, it is important to acknowledge that multicollinearity may still arise from more complex interactions among variables that are not captured through simple pairwise correlations.

3.2. Econometric Approach

The analysis investigates how geopolitical uncertainty shapes firm profitability over time and across countries. To explore this relationship, we specify a dynamic panel model that includes firm-specific controls, lagged profitability, and a country-level measure of geopolitical risk. The model takes the following general form:

In Equation (1), and , are countries and years, respectively, is the return of assets (ROA) for the firm i in year t, lagged dependent variable the firm i in year t − 1, is a matrix of control variables defined in the previous section while represents the geopolitical risk index in the firm’s country of operation. Finally, represents the error term.

To reduce potential endogeneity and unobserved heterogeneity concerns, the analysis moves beyond the standard linear specification by adopting a distributional framework. Specifically, both conditional and unconditional quantile regression methods are applied to capture how geopolitical risk affects firms situated at different points of the profitability distribution. The conditional quantile regression developed by ref. [23] focuses on the relationship between the explanatory variables and specific quantiles of the dependent variable, rather than its average value, making it possible to identify whether the effect of geopolitical risk varies across firms with lower, median, or higher profitability. This method provides a more comprehensive view of the underlying dynamics, revealing distributional heterogeneity that traditional mean-based estimations may overlook. For the panel setting, we rely on the conditional quantile regression estimator developed in ref. [24], which allows for consistent estimation of these effects across time and firms:

In Equation (2) is the dependent variable, is the set of covariates, is the common slope parameter, while is a location-shift parameter. To account for unobserved country-specific heterogeneity, ref. [24] treats fixed effects as nuisance parameters. The approach gains relevance by incorporating a penalty term into the objective function, which helps stabilize estimation and mitigate the influence of these effects on the quantile regression results:

In Equation (3), is the quantiles’ index, represents the quantile loss-function while is the relative weight associated with the th quantile. The penalty term, denoted as λ, is incorporated to reduce the impact of individual fixed effects towards zero. Furthermore, as λ approaches zero, the model tends towards a conventional fixed effects specification.

While the CQR is effective in analysing variables with asymmetric distribution, it generates coefficients that do not adequately represent the influence of these variables across different quantiles. To address this, ref. [25] introduced the unconditional quantile regression (UQR). This approach involves calculating a recentred influence function (RIF) that is independent of covariates, and then this function is regressed on the explanatory variables:

In Equation (4), , symbolizes the cumulative distribution function of , indicates the distribution that concentrates at the value , while is the value of the considered statistic. The RIF, representing an estimator ν with a probability distribution F at the point is determined by augmenting this statistic with its Influence Function (IF):

In Equation (5), the expected value of the RIF is , if the expected value of the is zero. When choosing the τth quantile as the statistic of interest and estimating the density functions using a Kernel density approach, the RIF, given can be defined in the following manner:

In Equation (6), is the τth quantile of the unconditional distribution of banking profitability, express the pdf of conditioned by the τth quantile, while is an indicator function indicating if is below the τth quantile. Finally, the UQR estimator is given by Equation (7):

The analysis relies on the standard implementation of Unconditional Quantile Regression (UQR) adapted for panel data, following the methodology introduced by ref. [26], which accounts for both country-specific and temporal fixed effects.

4. Results

In order to establish a rigorous foundation for our empirical investigation, we first examine the presence of a causal link between geopolitical risk and corporate profitability through panel causality tests and then quantify its average impact using a staggered Difference-in-Differences framework, since confirming both the existence and the direction of this relationship is a necessary condition for moving beyond mean effects and exploring distributional heterogeneity through unconditional quantile regression, as well as for addressing potential endogeneity in subsequent robustness checks.

4.1. Causality Analysis

A preliminary step in our empirical strategy is to assess whether geopolitical risk exerts a causal influence on corporate profitability. Compared to the initial data selection, we consolidated the industries into nine macro-sectors to avoid imbalances in representation and to maintain a tractable panel structure. The Dumitrescu–Hurlin panel causality test (ref. [27]) is then applied at this aggregated level. As reported in Table 2, the null hypothesis of no causality is rejected for almost all macro-sectors at the 1% level, confirming a systematic direction from geopolitical risk to profitability. The only exception is the primary and extraction sector, where the test does not indicate statistical significance. This suggests that the effect of geopolitical risk is broadly pervasive across the economy, while being less clear in resource-based activities. Overall, the results reinforce the importance of incorporating geopolitical risk as a determinant in subsequent firm-level panel estimations.

Table 2.

Dumitrescu and Hurlin causality test results.

4.2. Treatment Effect Analysis

To identify the causal effect of geopolitical risk on firm profitability, we rely on the staggered Difference-in-Differences framework of ref. [28]. Treatment is defined at the country–year level and corresponds to the GPR index exceeding the 80th percentile of its pre–2022 distribution. The rationale for using this threshold is twofold. First, it allows us to capture episodes of unusually high geopolitical tension, while avoiding the arbitrariness of absolute thresholds that may not be comparable across countries with structurally different baseline levels of risk. By anchoring the threshold within each country’s own historical distribution, we normalize for heterogeneity in average GPR levels, ensuring that treatment is triggered only by country-specific surges in risk rather than persistent structural differences. Second, restricting the benchmark period to the pre–2022 horizon prevents contamination from the extraordinary global shocks associated with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This makes the classification of high-risk states genuinely ex ante, so that post–2022 dynamics can be interpreted as treatment effects rather than determinants of the threshold itself. The key parameter of interest is the ATT (average treatment effect on the treated), which captures the average impact of high geopolitical risk on profitability across all treated firms.

The results reported in Table 3 indicate that firm profitability declines when countries face heightened geopolitical risk. The estimated treatment effect is negative and statistically significant, confirming that geopolitical shocks exert an adverse influence on corporate performance. The coefficients for the pre-treatment period are marginally significant at the 10% level, suggesting a slight deviation from the parallel-trends assumption but not enough to invalidate the identification strategy. In contrast, the post-treatment effects remain clearly negative and significant, supporting the view that geopolitical risk systematically erodes firm profitability in the years following exposure.

Table 3.

ATT estimates.

4.3. Unconditional Quantile Regression

In Table 4, we present the unconditional quantile regression estimates for return on assets as the dependent variable. The results indicate that the impact of geopolitical risk on firm profitability is both statistically significant and heterogeneous across the distribution. The coefficients are negative and highly significant at the lower quantiles, implying that firms operating with weaker financial performance experience a sharper decline in profitability when geopolitical uncertainty increases. This adverse effect gradually weakens toward the middle of the distribution and becomes positive and significant at the upper quantiles, suggesting that more profitable firms are better equipped to withstand, and in some cases benefit from, periods of geopolitical instability. These patterns highlight that geopolitical shocks amplify pre-existing asymmetries in corporate performance.

Table 4.

UQR results—Return on assets as dependent.

Firm size exhibits a positive and significant effect on profitability in the lower and middle segments of the distribution, indicating that economies of scale and market reach enhance returns among smaller and medium-sized firms. However, the coefficient becomes statistically insignificant in the upper quantiles, implying that the profitability advantage associated with firm size diminishes once a certain threshold of efficiency or market dominance is reached.

Leverage, measured by the debt-to-assets ratio, displays a strong and consistently negative association with profitability across all quantiles, with the effect being particularly pronounced among low-performing firms. This pattern confirms that higher indebtedness magnifies financial exposure and constrains firms’ flexibility under uncertainty. Tangibility also exhibits a uniformly negative coefficient, suggesting that a heavy reliance on fixed assets is associated with lower profitability, likely reflecting higher capital intensity and reduced adaptability to external shocks.

R&D intensity exerts a small but negative effect throughout most of the distribution, becoming statistically insignificant only in the upper quantiles. This finding indicates that innovation efforts are associated with short-term costs that compress margins for average or underperforming firms, while highly profitable firms are able to absorb these costs more effectively. By contrast, sales growth shows a consistently positive and significant effect across all quantiles, reinforcing the role of commercial expansion and market reach as key drivers of profitability.

Governance-related variables exhibit distinct distributional patterns. The gender of the CEO has no measurable effect among weaker firms but becomes positive and significant from the median onward, implying that leadership diversity contributes to performance mainly once firms achieve operational stability. Similarly, the coefficient for bank affiliation shifts from negative at the lower quantiles to strongly positive at the upper tail, suggesting that professional financial intermediation enhances profitability only when firms have sufficient capacity to utilize such support effectively.

Finally, macroeconomic conditions exert differentiated effects across the profitability distribution. Economic growth contributes positively to return on assets at both the lower and upper quantiles, implying that firms at the extremes of performance are more sensitive to fluctuations in aggregate demand. Inflation, conversely, becomes increasingly positive and significant from the median upward, reflecting the ability of stronger firms to adjust prices or manage costs more efficiently under inflationary pressures. Overall, the explanatory power of the model is highest in the lower quantiles, confirming that the profitability of weaker firms is more closely tied to observable financial and structural characteristics, whereas top-performing firms are influenced by more idiosyncratic and strategic factors beyond traditional financial indicators.

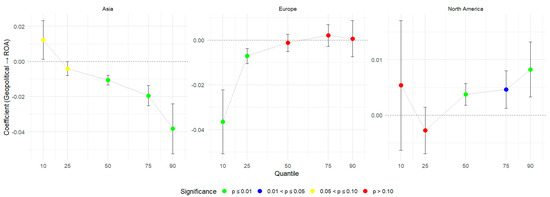

We move forward to a more granular analysis by examining whether the general patterns identified at the global level also hold across continents. In Asia, the negative association between geopolitical risk and profitability becomes stronger along the distribution and is particularly pronounced at the upper quantiles, where even highly profitable firms record significant losses in performance. This contrasts with the global finding, where resilient firms could leverage geopolitical turbulence. The evidence suggests that in Asia, exposure to trade networks and supply-chain dependencies magnifies the vulnerability of top performers, indicating that the general negative effect not only persists but intensifies for firms that would otherwise appear more robust.

In Europe, the results largely confirm the earlier conclusion that weaker firms are most exposed, as the strongest negative and significant effect is concentrated at the lower tail of the distribution. For mid- and high-performing firms, the coefficients flatten and lose significance, indicating that these firms have the capacity to absorb or mitigate geopolitical shocks, consistent with the global evidence. In North America, however, the picture diverges: the relationship is insignificant or even weakly negative at the lower quantiles but turns positive and significant at the top, suggesting that the most profitable firms may actually benefit from geopolitical turbulence through market consolidation or strategic repositioning. This implies that while the general pattern of vulnerability at the lower tail is confirmed for Europe and Asia, in North America the capacity of leading firms to transform geopolitical shocks into opportunities becomes the dominant effect.

The results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

UQR Estimates by continent. Source: Own processing.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

Building on the baseline quantile regressions, this section investigates the sources of heterogeneity in the impact of geopolitical risk on firm profitability. To this end, we interact the geopolitical risk index with key firm-level dimensions including asset structure, leverage, tangibility, R&D intensity, and sales growth to capture how financial and operational characteristics shape the distributional response to geopolitical shocks. The results are reported in Table 5. To ensure that the interaction terms are economically meaningful, each firm characteristic was divided into three groups, and the lower and upper terciles were used to represent firms with low and high exposure, respectively. The specification therefore includes the geopolitical risk index, the low and high characteristic indicators, and their respective interactions, allowing for a balanced comparison across the profitability distribution.

Table 5.

UQR results.

The results reveal a clear pattern of heterogeneity. The interaction between geopolitical risk and high-leverage or low-liquidity firms is negative and significant at the lower quantiles, indicating that financially fragile firms suffer a sharper decline in profitability when geopolitical tensions rise. By contrast, firms with higher tangibility, stronger asset bases, and more intensive R&D activity display positive and significant interactions at the upper quantiles, suggesting that these firms are better equipped to adapt and even benefit from elevated geopolitical uncertainty.

At lower quantiles, the direct effect of geopolitical risk becomes statistically insignificant in most specifications, which suggests that its influence is weaker among firms located in the lower tail of the distribution. This pattern occurs because the sensitivity of these firms to geopolitical shocks depends more on their internal characteristics such as asset structure, leverage, and innovation intensity, which are reflected through the interaction terms. Once these interaction effects are included, much of the variation that would otherwise be attributed to geopolitical uncertainty is captured by the combined influence of firm-specific factors. This indicates that geopolitical shocks tend to operate indirectly through differences in firms’ financial or operational structures rather than through a uniform, standalone effect.

4.5. Endogeneity Concerns

It is important to account for the persistence of profitability and the potential endogeneity of explanatory variables when analyzing firm performance. The System-GMM framework addresses these concerns, and the results confirm that return on assets exhibits strong persistence, with the lagged dependent variable being positive and highly significant across all specifications. Once endogeneity is controlled for, geopolitical risk emerges with a negative and statistically significant coefficient in all models, showing a robust adverse effect on firm profitability.

The extended specifications highlight the role of both firm-level and macroeconomic factors. Larger firms tend to display higher profitability, while higher debt ratios, greater asset tangibility, higher sales, and increased R&D intensity are all associated with lower ROA. Bank affiliation is positively significant, while the female leadership variable is weakly positive. At the macro level, growth and inflation show small but significant positive coefficients. Taken together, the System-GMM results from Table 6 demonstrate that, after accounting for persistence and endogeneity, geopolitical risk has a robust negative impact on profitability, and the additional firm-specific and macroeconomic variables further refine the understanding of profitability dynamics.

Table 6.

SYS-GMM results.

Although the dynamic panel model shows that geopolitical risk has, on average, a negative impact on firm profitability, this result reflects a central tendency that masks important differences across firms and regions. The mean effect is driven mainly by the large number of companies with modest or weak profitability, which are more exposed to external shocks and dominate the global sample. The quantile and regional analyses reveal that the negative average response coexists with heterogeneous outcomes, i.e., fragile firms experience pronounced declines, while highly profitable or well-diversified firms display resilience and, in some cases, benefit from market reallocation during periods of geopolitical tension. Taken together, these findings indicate that the overall negative impact represents an aggregation of asymmetric firm-level responses, shaped by differences in financial strength, adaptive capacity, and regional structure.

4.6. Quantile Machine Learning

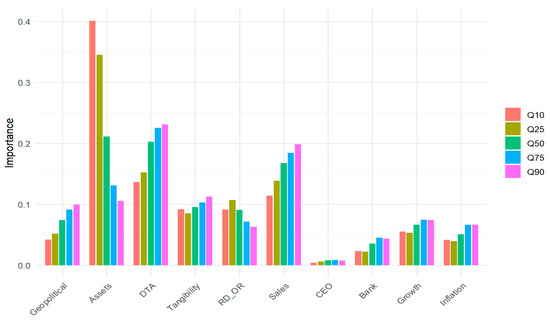

To complement the econometric analysis, we employ a quantile regression framework based on machine learning, specifically quantile random forests. This method is well suited for settings in which relationships between variables may be nonlinear or shaped by complex interactions, since it does not impose parametric assumptions on the functional form linking profitability and its determinants. The approach estimates firm profitability separately at different points of the outcome distribution (10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles). For each quantile, we train a dedicated model and evaluate the relevance of explanatory variables through a permutation-based importance measure. The procedure works as follows: first, we obtain baseline predictions and compute the quantile-specific prediction error using the pinball loss function, which is the standard loss for quantile regression. Then, for each explanatory variable, we randomly permute its values across firms while holding the others fixed, re-estimate the predictions, and recalculate the pinball loss. The increase in loss relative to the baseline reflects the marginal contribution of that variable to predictive accuracy at the given quantile. By repeating this procedure across quantiles, we obtain a distributional profile of variable importance that captures heterogeneous effects which conventional parametric quantile regressions may not reveal.

The results presented in Figure 3 indicate that geopolitical risk has a distinctly distribution-dependent role in shaping profitability. Its relative importance is limited at the extreme tails (10th and 90th percentiles), suggesting that very weak firms may already be constrained by internal inefficiencies, while top-performing firms are more resilient and better able to absorb shocks. By contrast, geopolitical risk becomes more influential in the central part of the distribution, with its highest importance around the median and upper-middle quantiles (50th and 75th). This pattern implies that firms with moderate or moderately high profitability are most exposed to external uncertainty, potentially because they are more engaged in international trade, global supply chains, or investment projects sensitive to political instability. Compared with structural firm-level factors such as total assets or leverage, geopolitical risk exerts a more selective but strategically significant influence, reinforcing the need to account for external shocks when assessing profitability dynamics.

Figure 3.

Comparative Variable Importance Across ROA Quantiles (Permutation-Based ML Estimates). Source: Own processing.

5. Discussions

Our results indicate that weaker firms located at the lower end of the profitability distribution are the most adversely affected by increases in geopolitical risk. This finding carries direct implications for investors and capital markets. The disproportionate exposure of such firms implies that investors may require higher expected returns when allocating capital to them, consistent with evidence on the higher cost of equity under geopolitical uncertainty documented by ref. [3]. By contrast, more profitable firms appear less sensitive to geopolitical shocks and, in some cases, are even able to exploit them, which supports the notion of “flight to quality” whereby both investors and customers gravitate towards larger and financially stronger companies in periods of turmoil. This reallocation of resources may partly explain why risk premia diverge across firms and why geopolitical shocks accelerate industry consolidation.

For corporate managers, the evidence underscores the importance of recognizing heterogeneity in exposure and designing resilience strategies tailored to firm characteristics. Companies with high leverage or weak liquidity buffers are significantly more vulnerable to shocks, particularly at the lower quantiles of profitability, which suggests that financial flexibility is a critical determinant of survival in uncertain environments. Proactive strategies such as geographic diversification, supply chain adjustments, or financial hedging can mitigate these risks, while investment in innovation and R&D may strengthen long-term adaptive capacity. Our interaction results show that firms with stronger asset bases or higher R&D intensity are better equipped to absorb geopolitical uncertainty, emphasizing that resilience is not only a matter of size but also of strategic orientation.

The heterogeneity documented here also has implications for policymakers concerned with financial stability. If geopolitical shocks primarily depress profitability among smaller and financially fragile firms, the aggregate outcome may be an increase in business failures and credit defaults concentrated in specific market segments. This suggests that policy responses during episodes of elevated global risk should incorporate targeted measures to support vulnerable firms, for instance through liquidity facilities, credit guarantees, or temporary tax relief. By stabilizing weaker firms, such interventions can mitigate systemic risk and prevent cascading effects on employment, investment, and supply chains. At the same time, policymakers should remain aware that stronger firms may consolidate market power during crises, with long-term implications for competition and market structure.

Finally, our findings contribute to the broader literature on risk perception and firm performance. The results align with ref. [5], who show that even minor changes in the salience of risk can alter investment flows, highlighting how behavioral channels interact with fundamental exposures. In our context, the asymmetry in profitability responses to geopolitical risk illustrates how investors, managers, and policymakers interpret and act upon uncertainty in ways that reshape financial outcomes. By demonstrating that geopolitical risk is not uniformly transmitted across firms but mediated by financial structure and strategic attributes, this study extends existing theories of risk in corporate finance and connects them to ongoing debates about resilience, investor behavior, and policy design in an era of heightened geopolitical instability.

6. Conclusions

This paper investigated the impact of geopolitical risk on firm profitability using a global panel of over 7000 listed companies between 2013 and 2023. By combining panel causality tests, staggered Difference-in-Differences, unconditional quantile regressions, and machine learning methods, the analysis provided one of the most comprehensive assessments of how external uncertainty affects firm performance.

The results consistently show that geopolitical risk exerts a negative causal effect on profitability, with the impact being highly heterogeneous across the distribution. Less profitable and financially fragile firms experience the sharpest declines, while more profitable firms often absorb or even capitalize on turbulence. Interaction models highlight that leverage, liquidity, asset tangibility, R&D intensity, and sales growth systematically shape this heterogeneity, confirming that financial structure and strategic orientation mediate exposure to geopolitical shocks.

The study contributes to the literature by moving beyond average treatment effects and uncovering distributional and structural channels through which geopolitical risk affects corporate outcomes. It also demonstrates how econometric and machine learning approaches can be jointly used to identify not only whether firms are vulnerable, but also which firms are most vulnerable.

Naturally, the analysis has limitations. Our sample focuses on listed firms, which may underrepresent smaller or privately held companies that could be even more exposed. Moreover, while the models capture major firm characteristics, other dimensions such as global supply chain integration or political connections remain difficult to quantify at scale. Future research could extend the dataset to unlisted firms, incorporate network-based measures of international exposure, and examine in more depth the role of managerial strategies in mitigating geopolitical risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D., B.A.D., P.T., I.L. and D.P.; Data curation, B.A.D., P.T., I.L. and A.-M.B.; Formal analysis, B.A.D., P.T., A.-M.B. and D.P.; Investigation, I.D.; Methodology, I.D., B.A.D., I.L. and A.-M.B.; Software, I.L. and A.-M.B.; Validation, I.L. and A.-M.B.; Writing—original draft, I.D., B.A.D., P.T., I.L., A.-M.B. and D.P.; Writing—review & editing, I.D., B.A.D., P.T., I.L. and D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results in this study were made available through the ORBIS platform, to which access was provided by the Bucharest University of Economic Studies. Data can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Caldara, D.; Iacoviello, M. Measuring Geopolitical Risk. Am. Econ. Rev. 2022, 112, 1194–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, W. Geopolitical risk and investment. J. Money Credit Bank. 2023, 55, 1125–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, R.; El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Wang, H. Geopolitical risk and the cost of capital in emerging economies. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2024, 61, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringpong, S.; Maneenop, S.; Jaroenjitrkam, A. Geopolitical risk and firm value: Evidence from emerging markets. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2023, 68, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugerman, Y.; Steinberg, N.; Wiener, Z. The exclamation mark of Cain: Risk salience and mutual fund flows. J. Bank. Financ. 2022, 134, 106332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi, M. Executive characteristics as moderators: Exploring the impact of geopolitical risk on capital structure decisions. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 93, 103188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, A.; Reig, A. Operating leverage and profitability of SMEs: Agri-food industry in Europe. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 57, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killins, R.N. Firm-specific, industry-specific and macroeconomic factors of life insurers profitability. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2020, 51, 101068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanin, T.I.; Sarker, A.; Hammoudeh, S.; Batten, J.A. The determinants of corporate cost of debt during a financial crisis. Br. Account. Rev. 2024, 56, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.H.; Hrdý, M. Determinants of S.M.E.s capital structure in the Visegrad group. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2166969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.K.; Pattnaik, D.; Kumar, S. Trade credit and firm profitability: Empirical evidence from India. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 27, 3934–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, F.; Serrasqueiro, Z.; Ramalho, J.J.S. Is zero leverage good for firms performance? Eur. J. Financ. 2025, 31, 749–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau Vera, D.; Sogorb Mira, F. What determines intragroup debt financing. Rev. Contab. Span. Account. Rev. 2024, 27, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacova, M.; Krajcik, V.; Michalkova, L.; Blazek, R. Valuing the Interest Tax Shield in the Central European Economies: Panel Data Approach. J. Compet. 2022, 14, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, Y.; Bilgin, R. The effect of the number of bank relationships on firm leverage: High-risk shift and the curse of mainstream banks. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 626–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulos, A.; Dassiou, X. Bank market power and performance of financial technology firms. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 29, 1141–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, D.; Baker, H.K. Factors affecting trade credit in India. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 88, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyi, C.O. Do the same executive compensation strategies and policies fit all the firms in the banking industry? New empirical insights from the CEO pay–firm performance causal nexus. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 4136–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Adelaja, A.O. Predicting acquirers of US food and agribusiness firms. Agribusiness 2025, 41, 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, A.P. Corporate Profits and Investment in Light of Institutional and Stock Market Turmoil: New Evidence from the Warsaw Stock Exchange. J. Econ. Issues 2021, 55, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakir, M.S.; Ova, A. The impact of economic policy uncertainty on the profitability of textile industry: Evidence from BRIC countries. Appl. Econ. 2025, 57, 1761–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.; Ha, V.; Le, H.H.; Ramiah, V.; Frino, A. The effects of polluting behaviour, dirty energy and electricity consumption on firm performance: Evidence from the recent crises. Energy Econ. 2024, 129, 107247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R.; Bassett, G.J. Regression quantiles. Econometrica 1978, 46, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R. Quantile regression for longitudinal data. J. Multivar. Anal. 2004, 91, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firpo, S.; Fortin, N.M.; Lemieux, T. Unconditional quantile regressions. Econometrica 2009, 77, 953–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgen, N.T. Fixed Effects in Unconditional Quantile Regression. Stata J. 2016, 16, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, E.-I.; Hurlin, C. Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ. Model. 2012, 29, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, B.; Sant’Anna, P.H.C. Difference-in-Differences with multiple time periods. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).