Abstract

This conceptual review article critically examines the systemic features and contradictions of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) and the ‘opportunity/danger paradox’ in the development and deployment of large language models (LLMs). The paradox and its potential resolution are explored through a political–economy–ecology framework. Through new developments in neo-Gramscian analysis, the article conceptualizes GenAI as embedded within competing dominant and subordinate technological blocs within the context of Platform Capitalism 2.0, evolving as the latest phase of Computational Capitalism. In response, an alternative horizontally organized, multi-layered socialized system of GenAI is proposed to ultimately resolve the paradox. The article utilizes Lury’s concept of problem spaces and recomposed research problems to explore transitioning to this socialized system based on constructing multiple mediating layers of the alternative technological bloc, mediated by alliances of progressive technological organic intellectuals exercising a technological organic intellect. The conclusion addresses the challenges of passive revolution effects and transitioning compounded by the phenomenon of compressed technological time.

1. The GenAI Opportunity/Danger Paradox in a System Context

1.1. Situating GenAI Historically

When analyzing potential revolutionary technological changes, it is important to situate these historically. The trajectory of GenAI and LLMs can be seen to build on foundational technological advancements of previous decades—the advent of the desktop computer in the 1980s that democratized computing power, which, in turn, paved the way for the Internet’s emergence in the 1990s, creating a global network for communication and unprecedented information access [1,2]. Building upon these foundational elements and allied to the exponential increase in computational power in recent decades [3], breakthroughs in machine learning and neural networks have come to lay the ground for GenAI [4,5].

Large language models (LLMs) are now generating increasingly accurate human-like text with growing multi-modal capabilities being applied across multiple economic, social, and cultural contexts, resulting in a rapidly expanding LLM application layer [6]. At this point it is important to distinguish between and relate definitions of generative AI (GenAI) and large language models (LLMs). GenAI refers to a class of artificial intelligence systems designed to produce new content—text, images, audio, or code—based on learned patterns. LLMs, on the other hand, represent a leading variant of GenAI, specialize in the generation and understanding of human-like text. However, the development of multi-modal capabilities in LLMs to become large multi-modal models (LMMs) [6], is blurring the distinction between these two categories.

Accompanying these developments has been LLM platform diversification, in which geopolitical competition is creating a multipolar GenAI world very different from the 2022 days of ChatGPT’ 3.5 ascendancy. By mid-2025, US tech organizations continued to lead with no fewer than 40 ‘notable’ AI models and a range of specialized models developed within a small number of highly funded companies [7]. China, on the other hand, has so far consolidated an estimated 15 top-ranking models, distilled from the initial ‘war of a 100 models’ aimed at closing the gap with the US [8,9]. Intensifying US–China geopolitical competition is now central to the near future of GenAI development [10,11], highlighting the importance of situating technological developments not only historically, but also in relation to globalized economic and political system contexts.

In this article, therefore, understanding whole GenAI systems refers to conceptualizing potentially regressive and progressive ensembles of techno-economic, social, political, cultural, and ecological relations [12,13], in relationship to the development of the various stages and differing forms of what has been termed ‘Platform Capitalism’ in the globalized context [14,15].

1.2. The GenAI Paradox

This systemic analysis raises questions, not only of the effects of rapid advances in technological power but, crucially, the motivation and purposes of human forces that produce the GenAI paradoxical challenge [16], reflected in the relationship between the potential powers of LLMs and their risks. LLM generative capacities is now being applied in diverse sectors (e.g., the growing application layer), including marketing and finance, education, academic research, healthcare, legal services and software development due to significant time savings, increase problem solving capabilities and the creation of autonomous agents [17,18], while, at the same time, producing significant dangers, including hallucination and misinformation, reinforcement of existing biases, academic dishonesty and intellectual over reliance [19,20]. Additionally, there are the rapidly unfolding challenges of labor displacement and energy/ecological costs of mass data generation [21,22], contributing to what has been termed the neoliberal poly crisis [23].

These recognitions lead to three related arguments for GenAI system transitioning. First, the GenAI opportunity/danger paradox is primarily the result of its symbiotic relationship with Platform Capitalism 2.0 due to the profit-seeking motivations of key actors. Second, this evolving capitalist system functions as a dominant technological bloc, exercising hegemony across multiple societal layers—techno-economic, ideological/historical political, social, and ecological. The recognition of bloc powers leads to a third related argument—that the opportunity/danger paradox cannot be meaningfully resolved without wider changes to the overall technological system in which it is being implemented, leading to the proposal for the development of a progressive socialized system of GenAI functioning as an alternative technological bloc.

2. Technological Blocs and Platform Capitalism 2.0

2.1. Assembling a Conceptual Toolkit for Analyzing GenAI Systems

An emerging neo-Gramscian theoretical toolkit can be seen to be increasingly attuned to the dynamics of the digital age to unpack the evolving configurations of coercion and consent surrounding generative AI (GenAI) within broader economic, political, and ecological contexts. Six adapted key concepts of this developing toolkit are explored in different parts of the article.

- Platform Capitalism 2.0 as the latest phase of Computational Capitalism.

- Vertically and horizontally organized Technological Sub-Blocs that exercise technological dominance and counter-hegemonies.

- Bloc Entanglement between these sub-blocs in the context of Platform Capitalism 2.0.

- Technological organic intellectuals who collaborate to form progressive technological alliances to cohere the alternative sub-bloc.

- The concept of a technological organic intellect, functioning as both a social unifying culture and as connective specialist knowledge and skill.

- The challenges of ‘Passive Revolution’ and ‘Technological Compressed Time’ in transitioning towards a socialized system of GenAI and resolving the GenAI paradox.

2.2. Neo-Gramscian Thinking—From Globalization to Climate Change and Digital Revolutions

The theoretical work of Antonio Gramsci [24] has been widely recognized as introducing a Marxist theory of politics and culture [25,26] with his foundational concept of ‘hegemony’—combinations of consent and coercion—used to help understand capitalist resilience and the challenges of building a new social order in Western democratic conditions [27,28].

In the 1980s and 1990s, neo-Gramscian theory was applied principally to an analysis of globalization and the domination of the neoliberal world order [29,30,31]. Burnham [31], for example, argued that neoliberal restructuring was the result of hegemonic projects shaped by elite interests, while Jessop [30], proceeded to suggest that globalization was a hegemonically constructed process, mediated through state strategies and class alliances. Morton [31], on the other hand, highlighted the transnational nature of hegemony and the importance of counter-hegemonic movements and the potential for resistance.

Neo-Gramscian analysis has also been applied to the politics of climate change. At the turn of the century, Levy and Egan [32], argued that climate governance was not just about environmental concerns, but a reflection of hegemonic struggles between transnational capital and civil society. More recently, Carroll [33], has focused on the politics of energy and ‘fossil capitalism’, while Winkler [34] has articulated the need for inclusive and equitable energy transitions and the role of civil society and labor movements in shaping transition pathways.

2.3. An Expanding Conceptual Toolkit for Digital Technologies

A new neo-Gramscian literature is now emerging in the field of digital technologies [35,36,37]. Timcke [35], offers a critical neo-Gramscian reading of data capitalism, focusing on how digital technologies reproduce class power, while Shad [36], examines the global governance of AI and the marginalization of ‘subaltern voices’ in AI ethics.

However, particular attention is paid here to Guglielmo’s expansive counter-hegemonic analytical toolkit [37], that reinterprets Gramsci’s ‘Modern Prince’ as the political party [24], through a triadic metaphorical framework—a ‘Map’ to chart ideological terrains of hegemonic domination, a ‘Compass’ to orient strategic direction towards an alternative digital future, and a ‘Toolkit’ comprising the political strategy of ‘war of position’ and the role of ‘digital organic intellectuals’.

This article builds on Guglielmo’s interpretations of dominant digital hegemony and his counter-hegemonic analytical toolkit by elaborating three complementary neo-Gramscian concepts—‘technological blocs/sub-blocs’, ‘technological organic intellectuals’, and the ‘technological general and organic intellects’. The task of building a socialized technological sub-bloc requires a broader array of counter-hegemonic activity than Guglielmo’s narrower focus on data commons, digital activism, and the ‘digital princess’ (an alliance of grassroots movements and left-wing political parties). Nevertheless, key elements of his Toolkit are incorporated into the alternative GenAI system elaborated in Section 4 and Section 5.

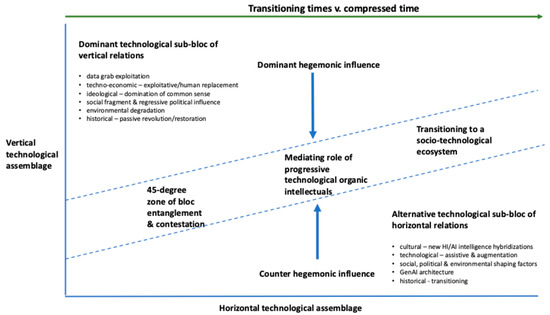

The dynamic relationship between the concepts of vertically and horizontally organized historical blocs/sub-blocs, bloc entanglement, technological organic intellectuals, in the context of Platform Capitalism 2.0 are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Vertical and horizontal assemblages and the 45-degree zone of entanglement.

2.4. From Platform Capitalism 1.0 to 2.0

Platform Capitalism, as a techno-economic model, has been characterized by the rise and dominance of digital platforms functioning as intermediaries in various sectors of the economy, ranging from ‘lean’ types like Uber, which owns few physical assets but controls a vast network of drivers and their cars, to more asset-heavy models such as the warehouse-based Amazon [14]. Through its diverse forms, this relatively new capitalist formation has fundamentally restructured markets by connecting differing groups-users, producers, advertisers, and consumers [15]—through the systematic extraction and commodification of data on human behavior used as a predictive asset for targeted advertising and product development [13]. The hegemonic effect of this ‘platformisation’ has been to promote a narrative of ‘progress’ through neoliberal versions of connectivity and exchange [38].

The Platform Capitalism 1.0 phase of Computational Capitalism, however, has undergone significant evolution in recent years with the rapid emergence of GenAI, producing a qualitative shift from a data-extractive business model to a data-generative one [39]. While the initial phase of Platform Capitalism focused on monetizing user-generated data and network effects, GenAI has allowed platforms to actively produce content, automate services, and create simulated interactions that move beyond intermediation to become a primary creator of value [39]. These techno-economic shifts have been combined with wider geopolitical developments, leading to what is termed here ‘Platform Capitalism 2.0’. Its key features and contradictions are illustrated in Table 1 that, through processes of comparison, also produce questions focused on alternative ideas and practices.

2.5. Platform Capitalism as a Technological Sub-Bloc

Gramsci conceived of a historical bloc as an economic, political, social, and cultural assemblage through which a ruling group can exercise hegemony, utilizing the coercive and bureaucratic authority of the state, its dominance in the economic realm, together with the consensual legitimacy of civil society [24,32]. As Figure 1 illustrates, the concept of historical blocs is conceptualized here as vertically and horizontally organized assemblages of various layers of societal power—economic, political, social, cultural, and environmental [25]—involved in dynamic and often contradictory relationships [40], and with the potential to function as a strategic political concept of historical bloc construction [41].

Building on the original Gramscian concept of historical bloc, a new analytical category is proposed—a ‘technological sub-bloc’ that acts as a leading force within the overall historical bloc. A neoliberal technological sub-bloc is seen as mainly vertically organized, comprising a specific alliance of actors—Big Tech companies, venture capital, aligned policymakers, and key institutional users—that coordinate techno-economic, ideological, political, and social relations in the maintenance of economic and ideological hegemony of contemporary capitalism [42].

While Gramsci has been recognized for his foundational contribution to Marxist political and cultural theory, he remained nevertheless a historical materialist, reflected in his political-economy analysis of ‘Americanism and Fordism’ [43]. In the context of economic developments in the 1920s and 1930s, he interpreted the emergence of mass production as leading to a new global order, later recognized as the Keynesian era.

And so, it is with Platform Capitalism. The dominant technological sub-bloc is conceptualized here as more than a technical layer of the overall historical bloc. It constitutes a new mode of production rooted in data extraction, algorithmic control, platform infrastructure, and monopolistic capital [44], also referred to as a phase of ‘Computational Capitalism’ [45], and as ‘Surveillance Capitalism’ [13]. Operating as a leading innovative and disruptive force, this vertically organized sub-bloc exercises techno-economic powers and hegemonic narratives of progress and efficiency to shape societal relations [37].

2.6. The Anatomy of Platform Capitalism 2.0

As Table 1 illustrates, the globalized Platform Capitalism 2.0 is conceptualized as a vertically organized assemblage of relations—techno-economic, ideological/historical, epistemological, political, social, and ecological—operating through a combination of corporate power, governmental state, and transnational political structures. The bloc, at its most politically and ideologically ambitious, also reached into civil society to structure relations of consent. These hegemonic functions and their contradictions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Platform Capitalist Bloc 2.0—key layers, contradictions, and alternative questioning.

Table 1.

Platform Capitalist Bloc 2.0—key layers, contradictions, and alternative questioning.

| Bloc Layers | Key Features of GenAI Drive Platform Capitalism 2.0 | Contradictions and the GenAI Paradox | Recomposed Questions Around Alternative Ideas and Practices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Techno-data | Data extraction and data generation and commodification and now content generation | Data scarcity and exploitation of private and public data | What alternative ideas about socialized data generation are emerging? |

| Ideological | Hegemonic narratives of progress, efficiency, human replacement | Amplification of pre-existing prejudices; human/AI alienation relationship | What are the new narratives around future distributed hybrid human/AI intelligence knowledge relationships? |

| Epistemological | Epistemological chaos | Generation of inauthentic material, blurring fantasy and reality | In what ways can GenAI be used to engage with complex realties? |

| Political | Deregulation, corporate lobbying, algorithmic control | Less democratic oversight, new digital authoritarianism | What are the key ideas around accountability regimes and popular technological participation? |

| Social | Individualism, surveillance capitalism, data as consumption and generation | Social distraction and fragmentation, privacy erosion | How can social relational approaches be developed for GenAI? |

| Economic/ environmental | Monopolies, high energy use, and resource depletion. | Labor displacement, ecological footprint and externalized costs | How can GenAI become part of high-skill augmentation and a greener economy? |

| Globalized/ relational | Two global systems of GenAI—US and Chinese | Fracturing within the dominant global bloc | What are the consequences of Chinese GenAI for the alternative socialized model? |

Sources [12,13,14].

2.7. Dimensions and Contradictions of the Platform Capitalist 2.0 Sub-Bloc

Techno-data dimension—this key dimension of the dominant technological sub-bloc drives its relationship to the wider historical bloc and the transition from Platform Capitalism 1.0 to 2.0. A new phase of capitalist production and accumulation reflects fundamental shifts in the digital economy, defined by an intensified ‘data grab’ driven by the needs of increasingly powerful LLMs. These are creating a new ‘data scarcity’ of high-quality, clean information [46], that reinforces the monopolistic positioning of Big Tech firms over data control and essential cloud computing infrastructure, thus allowing firms to extract ‘rent’ for their use [47].

Ideological dimension—the dominant technological sub-bloc is cohered not only through technological and economic power, but also through the role of ‘regressive’ organic intellectuals, exemplified by Big Tech founders, notably Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, through platforms like X and Meta, to actively shape public discourse [48], to create a technological variant of ‘neoliberal common sense’ [49,50]. The role of these tech leaders has also been replicated internationally, with figures like Klaus Schwab and the transnational World Economic Forum, constructing an additional ideological apparatus for the sub-bloc by providing a global platform where corporate leaders and policymakers can converge to promote a common narrative around concepts such as the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ [51], that has framed corporate-led innovation as the only viable path forward [52,53].

Epistemological dimension—the ability of LLMs to generate vast quantities of convincing, yet often inauthentic content, is producing what has been termed ‘epistemological chaos’—a social erosion of the ability to distinguish between what is real and what is fabricated [54]. The production of ‘synthetic realities’ is exercising a disruptive effect on traditional institutions’ epistemic authority [55], fueling public suspicion and a decline in trust [56].

Political, economic, and environmental dimensions—the transitioning to Platform Capitalism 2.0 has also been marked by political, ecological, and labor market regressions. Politically, giant tech firms actively engage in political lobbying to secure favorable regulations and solidify monopolistic positions [57,58]. This positioning has resulted in an arms race to develop more powerful LLMs, resulting in enormous resource consumption, highlighted by unsustainable energy and water costs of data centers [59,60]. These political and environmental strains are compounded by labor displacement, with jobs involving routine cognitive tasks increasingly threatened [61].

The global dimension of geopolitical competition and Chinese GenAI—while Chinese technological innovation does not constitute an alternative socialized system, it is fracturing the globalized formation of Platform Capitalism 2.0. On the surface, the market topography of the US and China looks similar (e.g., competing big companies), but underneath lie differing political economy logics [62], that reflect varieties of capitalism—liberal market and coordinated [63]. China’s strategic ‘whole nation’ commitment to LLM development is evidenced by substantial national investments and supportive policies in AI research and infrastructure [64], a strategy aimed at accelerating the development of multiple, efficient, open-source, and specialized models not only within the Chinese GenAI-societal ecosystem, but also as part of a low-cost globalized ‘Digital Silk Road’ [65,66]. The global fracturing effect was exemplified in early 2025 with the arrival of the open-source Chinese LLM DeepSeek V3 that shook up the AI world due to the combination of high capability and low computational costs compared with US models, allowing its underlying architecture to be widely adopted for LLM customization [67].

2.8. Bloc Entanglement, Contestation and Mediation

Although bloc contestation is currently unequal, the dominant and alternative sub-blocs are involved in a constant state of ‘entanglement’ in the ongoing struggle over the historical direction of GenAI. As a potential counter-hegemonic force, the alternative sub-bloc can benefit from the contradictions of the dominant formation to provide the dynamic ‘problem spaces’ [68], where strategic questions can be raised and radical interventions envisioned (see Table 1).

As illustrated in Figure 1, moments of bloc entanglement occur mainly within the ‘45-degree zone of contestation and mediation’. This is not conceived as a fixed point between the vertical and horizontal axes, but as a dynamic relationship between the two competing systems that shifts vertically and horizontally according to alignments/misalignments of both blocs and the powers of hegemonic/counter-hegemonic influence [25]. It is within these highly contested spaces that layers of ‘progressive mediation’ can be built between the technology and users, led by alliances of technological organic intellectuals of the alternative bloc.

2.9. Technological Organic Intellectuals

Gramsci’s concept of the organic intellectual remains vital for understanding the cultural and political dynamics of contemporary technological development. He saw organic intellectuals not as ‘traditional’ thinkers (men of letters’ as he put it), but as active organizers whose mission is to cohere historical blocs—dominant and subordinate [40]—by shaping the worldview of a social class to secure hegemonic or counter-hegemonic projects [24].

The dominant technological sub-bloc, in the form of global tech companies, has cultivated a powerful cadre of ‘regressive’ organic intellectuals who exercise techno-economic and cultural leadership [69,70]. Alongside them are ‘technical intellectuals’—the engineers and developers who build GenAI systems and who occupy potentially contradictory positions, being both agents of the platform capitalist hegemony and a strategic constituency for counter-hegemonic engagement [13]. Beyond the producers are the key users of GenAI—private and public organizations and wider digital publics. A key challenge for the organizers of both sub-blocs -regressive and progressive—is alliance building among these dispersed groups. The idea of technological alliance construction is elaborated in Section 4.

2.10. Platform Capitalism 2.0 and the GenAI Paradox

Despite considerable economic, political, and ideological powers, the dominant technological sub-bloc contains significant internal contradictions. These include the mass exploitation of public and private data, increasing labor displacement, new digital authoritarianism, social fragmentation, ideological echo chamber effects, and unsustainable ecological footprints (see Figure 2).

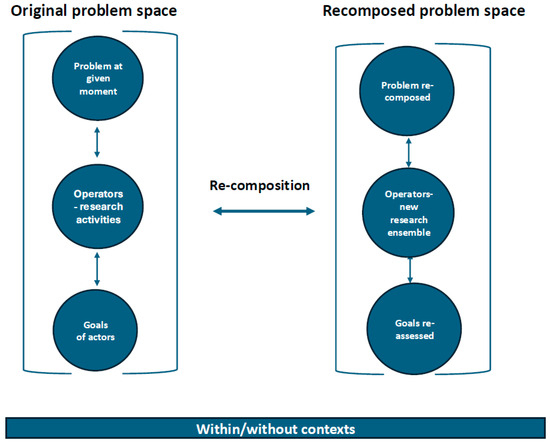

Figure 2.

Interpreting Lury’s concept of evolving problem spaces.

However, it is important to recognize that these contradictions have double-edged effects—they can stimulate alternative thinking and practice while, at the same time, reducing the possibility of an alternative vision of GenAI emerging in the popular imagination by virtue of the effects of dominant technological organic intellectuals and their apparatuses on societal thinking [37].

Appreciating this dilemma, the remainder of the article focuses on recomposed questions concerning future alternative socialized technological possibilities, based not only on responses to the key contradictions of the dominant model but, crucially, through the construction of counter-hegemonic imaginaries articulated by alliances of various types of technological organic intellectuals.

3. Researching GenAI Problem Spaces

3.1. The GenAI Paradox and Transition Challenges as Evolving Problem Spaces

In view of the complexities of the GenAI paradox and the challenges of transitioning from Platform Capitalism 2.0 to an alternative system, Lury’s related concepts of ‘problem spaces’ and ‘compositional methodology’ [68], have been adapted to help explore potential research approaches to the dynamic configurations of actors, factors, activities, and equilibria within technological systems locked in contestation. Her chronological multi-level system approach can be seen to build on DeLander’s work on assemblage theory [71].

Lury’s groundbreaking work conceptualized the evolving inter-relationship between three key elements—the ‘problem’ at any given moment; the ‘goals’ of actors involved in the problem space are working towards; and ‘operators’—the actions, methods, and practices applied to understand and transform the problem space. As a way of researching the evolving problem space, she also calls for a ‘compositional methodology’ in which researchers must compose new ways of interacting with the unfolding phenomenon. The key to these twin concepts is the reciprocal interplay between the elements as a continuous feedback loop in which evolving problem spaces, affected by ‘without/within’ contextual influences, are perpetually in a state of ‘re-composition’. Lury’s fluid research approach thus challenges traditional views of research as a static, given problem and the idea of researcher ‘independence’ in research, by arguing for a process of constant engagement and reflection on an evolving phenomenon.

3.2. Extending the Problem Spaces Model

Building on her contribution to participatory research approaches, the concepts of problem space, compositional methodology, and problem/question re-composition are integrated into a neo-Gramscian conceptual framework to provide an extended problem spaces model capable of explaining transitioning from the dominant technological system/bloc to an alternative socialized version.

Figure 2 represents an interpretation of Lury’s original problem space model comprising key inter-related factors—within/without contextual influences and movement from the ‘given’ problem space to a ‘re-composed’ condition.

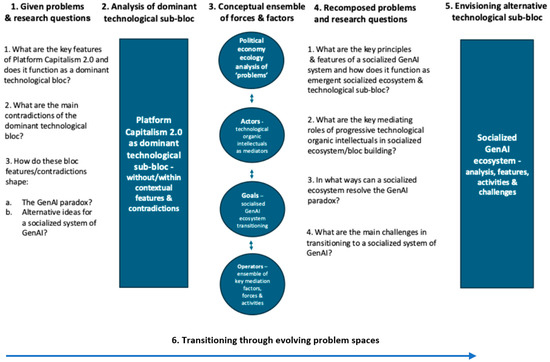

In Figure 3, the extended model applied to technological transitioning leads to six research elements listed below and elaborated in various parts of the article.

Figure 3.

A political–economy–ecology–technology adaptation of problem spaces.

3.2.1. Initial Given Problems/Questions

The research process begins with a set of ‘given’ problems framed as initial questions to explore the key characteristics and contradictions of dominant technological blocs and their relationship with the GenAI paradox.

- a.

- What are the key features of Platform Capitalism 2.0, and how does it function as a dominant technological sub-bloc?

- b.

- What are the main contradictions of this technological sub-bloc?

- c.

- How do these sub-bloc features/contradictions shape the GenAI paradox and alternative ideas for a socialized system of GenAI?

3.2.2. Analysis of Platform Capitalism 2.0 as the Dominant Sub-Bloc

An analysis of the ‘given problem space’ focuses on contradictions and misalignments of the dominant sub-bloc, giving rise to the complex challenges of the GenAI paradox.

3.2.3. Conceptual Ensemble of Forces and Factors

The Lury ensemble of ‘given problems’, ‘goals’, and ‘operators’ is supplemented by the role of ‘connective actors’ through an exploration of the mediating functions of different types of technological organic intellectuals in GenAI bloc building.

3.2.4. Recomposed Questions

As a result of the activity of the ensemble of forces and factors, a set of recomposed research questions emerge concerning the features and challenges of transitioning to an alternative socialized GenAI system/bloc.

- a.

- What are the key principles and features of a socialized GenAI system, and how does it function as an alternative technological sub-bloc?

- b.

- What are the mediating roles of progressive technological organic intellectuals?

- c.

- In what ways can a socialized system resolve the GenAI paradox?

- d.

- What are the main challenges in building a socialized system of GenAI?

3.2.5. Envisioning an Alternative Socialized Technological Sub-Bloc

3.2.6. Transitioning Through Evolving Problem Spaces

The challenges of gradually transitioning from the dominant bloc to alternative socialized bloc to resolve the GenAI paradox are also seen as evolving problem spaces. These research-related issues are discussed in the final Section 5.

Actors involved in complex problem space recomposition will necessarily involve researchers working in collaboration with various producer and user communities in the field of GenAI. Conceptualized as alliances of mediating technological organic intellectuals, these actors will face challenges of developing a rigorous analysis of the problems, establishing realistic goals for action, and assembling the mediating factors and forces (operators) capable of taking the initial steps in building/bloc building. This long and arduous process will be made all the more difficult by the continuous hegemonic actions of the dominant bloc and, thus, counterstrategies will have to be considered.

4. An Alternative Socialized System of GenAI

4.1. The Socialized System as an Alternative Technological Sub-Bloc

In contrast to the dominant vertically organized Platform Capitalist sub-bloc, the alternative socialized GenAI system, conceptualized as a progressive technological sub-bloc, is located along the horizontal terrains of civil society, both national and international. While located mainly in radical civil society, forces of the alternative sub-bloc will also be attempting to reform vertical structures [25]. It is from these twin locations that it challenges the dominant bloc principally in the zone of entanglement and contestation (see Figure 1). Put another way, the horizontalized socialized system cannot be created in isolation from the verticalized influences of the dominant formation; there is a process of constant struggle and challenge to emerge as a viable socio-technological alternative.

Recomposed questions, derived from the initial analysis of GenAI system development and alternative bloc building, are assembled here to guide the envisioning of the alternative socialized system.

- a.

- What are the key dimensions of a socialized GenAI system functioning as an alternative technological sub-bloc?

- b.

- What are the key mediating roles of progressive technological organic intellectuals, the technological organic intellect, and democratic governance in a socialized technological system?

- c.

- What are the main challenges of transitioning to a socialized system/bloc to resolve the GenAI paradox?

It is important to recognize, that through evolving problem spaces, the wider ‘without’ contextual technological, economic, and political factors move from being external constraints of the dominant sub-bloc pressuring the emergent GenAI architecture to become integrated political–economy–ecology support forces ‘within’ the socialized system. Moreover, as part of this strategic process, the ordering of system/bloc layers shifts. While techno-economic forces and factors of power lead the dominant bloc, in envisioning the alternative system/sub-bloc, priority is given to the creation of new technological cultures to establish the very idea of a socialized GenAI system.

4.2. Layers of the Alternative Sub-Bloc

Key principles of the alternative sub-bloc are its socialized, collaborative, and democratic character organized principally in national and transnational civil society contexts. At the same time, this horizontal technological assemblage must also reach into the vertical assemblage associated with the governmental state—national and transnational—particularly in relation to the development of assistive technological regulatory regimes (EC-JRC, 2025).

In contrast to the dominant technological sub-bloc characterized by techno-economic powers, alternative sub-bloc analysis prioritizes four inter-related layers—cultural-ideological, political-governance, technological-experimental, and ecological-economic—to establish the effectiveness of alternative ideas, practices, and structures in this early phase of alternative bloc development.

4.2.1. Cultural–Ideological Layer—Human–Machine Relationships

The foundational dimension of a new socialized system is the culture of potential human intellect (HI)—machine intelligence (MI) relationships. Thus far, much attention has been paid to the extrinsic capacity of machine intelligence to ‘mimic’ human-like behaviors, while deeper human intrinsic social, philosophical, political, and psychological dispositions have often remained peripheral [72,73]. Moreover, in the context of Platform Capitalism’s obsessions with super-intelligence [74,75], this relative neglect is particularly problematical in view of the centrality of human motivation in the initial programming, re-evaluation, and decisions about the usage of GenAI [76].

Conversely, to develop ‘progressive’ HI-MI fusions requires the exploration of the multifaceted qualities of human intelligence, conceptualized here as the human intellect, required to drive the relationship [77,78]. Like machine intelligence, human intelligence is not preset; it too requires development, suggesting the foundational principle of nurturing intrinsic ethical qualities of curiosity, mastery, autonomy, purpose, integrity, and the pursuit of meaning [79], to become an ’intellect’. In other words, what is required is an expansion of human intellectual disposition to contribute to social and political consciousness, emotional intelligence, practical intelligence, and experiential wisdom required for fusion processes, referred to as ‘collaborative intelligence’ [80]. At its core is a disposition towards ‘ontological humility’ [81], an openness and willingness to work with a diversity of views, including those offered by the machine.

Within the emerging human–machine relationship, it has been argued that the aim should be MI augmentation rather than the replacement of human intelligence [82,83]. While agreeing with the direction of the argument, the additive augmentation perspective may not adequately capture potential dialectical transformations in HI-MI co-evolving relationships. Therefore, new terminologies such as ‘hybrid intelligence’ and ‘synthesis knowledge’ [84], are considered in which HI-MI relationships move beyond the ‘extended mind’ tool concept [85], to form new synergistic cognitive units [77,80]. This socialized ensemble of human intellects and machine intelligence is elaborated in the section on the technological organic intellect and machine intelligence relationships.

4.2.2. The Democratic Political Governance Layer

The governance of GenAI presents a political challenge that extends beyond technical regulation and into the realms of democratic legitimacy and civic engagement, requiring the development of democratic frameworks, that function as layers of mediation that reorient technological development away from capitalist accumulation and toward public values, collective oversight, and inclusive participation.

A foundational element of this democratic governance is the establishment of robust regulatory regimes that ensure ethical development, deployment, and accountability of GenAI systems, emphasizing the need for algorithmic accountability, explainability, and human oversight as core principles of ethical AI governance [86,87]. The European Union’s AI Act, for example, represents a step toward rights-based regulation [88].

Beyond regulation lies the shift from centralized, corporate-controlled infrastructures to decentralized socio-technical systems that distribute power, control, and ownership, involving the development of public digital infrastructure, open-source platforms, and community-managed data commons [89,90]. Emerging models such as federated learning, distributed computing, and open-source LLMs (e.g., DeepSeek V3) exemplify the potential for decentralized architectures [91,92]. Democratic governance of GenAI also requires mechanisms for popular participation, enabling citizens not only to use AI tools, but also to shape their development and deployment, by active co-creation [93], the development of which can be seen as forming technological ‘communities of practice’ [94].

4.2.3. The Socialized Data Layer—Data Commons and LLM Customization

Addressing the ‘data scarcity paradox’ inherent in Platform Capitalism 2.0, a socialized GenAI system would also propose experimental models for shared, high-quality, ethically sourced, and community-contributed datasets, moving beyond the extractive ‘data grab’ mentality [95], to foster a collaborative and democratically governed data system. Central to this vision is the development of ‘data commons’—publicly accessible, collectively maintained repositories of data—governed by ethical principles and designed to serve societal purposes [37]. Data commons initiatives are emerging with the establishment of repositories like ‘Hugging Face’, that seek to distribute the means of creation away from a few centralized closed systems [96,97] and the data commons Model Context Protocol (MCP) aims to anchor LLMs to transparent public data [98,99]. These common initiatives could also be underpinned by mechanisms such as federated learning [100], privacy-preserving AI techniques, and open data initiatives that ensure equitable access, transparent use, and collective ownership [101].

Beyond data governance, the architecture of GenAI can be reimagined with an emphasis on open-source model architectures to enable ‘progressive customization’—allowing researchers, educators, and civil society actors to adapt and refine LLMs for specific social purposes, including university-developed open-source LLMs, research consortia pooling of computational resources, and open-source LLMs [91,102]. Open-source initiatives have become a widespread component of AI systems, with over 50 percent of enterprises reporting the use of open-source models, data, and tools in their technology stack [103], although, as will be seen, the extent of actual use remains limited.

Drawing on the principles of peer production [89], these models would contribute to the creation of a larger technological public domain: a shared digital infrastructure where knowledge, tools, and capabilities are co-produced and democratically governed. Moves for greater tech democracy and transparency have been exemplified by initiatives such as the HELM Leaderboards and Jailbreak Bench [104], to provide stakeholders with auditable tools necessary to assess safety, bias, and performance against public standards [105].

Despite their importance, however, radical civil society technological initiatives are not immune to political dangers. They can either function as the outriders and the foundations of a new socialized system, or they can be contained by Platform Capitalism through processes of ‘technological passive revolution’, in which they become innovation without change [106]. This fundamental dilemma is reviewed in Section 5.

4.2.4. The Ecology-Economic Layer—Strategies for Sustainable Futures

The relationship between GenAI and surrounding political–economy–ecology factors is also viewed as potentially dialectical—the purposes of GenAI architecture are shaped by these wider societal aims, while socialized GenAI provides an assistive role to fundamentally shift towards high skill and economically inclusive sustainable development. A socialized GenAI system, for example, could promote energy-efficient AI models, localized and decentralized computing solutions [90,92], and integrating ‘sustainability by design’ throughout the AI development and deployment lifecycle [107]. Moreover, a socialized GenAI system would be embedded within a high-skill economic development strategy, where AI augments human capabilities rather than the automation-centric logic of Platform Capitalism 2.0 that displaces them, reorienting GenAI toward labor-enhancing applications that support creative, analytical, and collaborative work, particularly in education, healthcare, and public services [108]. This economic reorientation aligns with radical economic models such as the doughnut economy [109], the circular economy [110], and converges with the emerging paradigm of Industry 5.0 [111], to prioritize human-centricity and sustainability over the narrower Industry 4.0 aims of automation and efficiency [112].

4.3. Technological General and Organic Intellects—The Philosophy of Socialized GenAI

This section discusses different versions of the General Intellect and suggests that these require extension to the multi-dimensional concept of the Organic Intellect that recognizes the importance of both general socialized consciousness and specialist technological thinking and activity in the production and use of GenAI. The section then considers the relationship between the combinational Organic Intellect and machine intelligence in the production of hybrid intelligence and fusion knowledge.

But first, it is important to examine the concept of the General Intellect that forms the social basis of the Organic Intellect. As an important but only recently recognized Marxist insight into technological development, the concept of the General Intellect has suffered historically from various limitations that have inhibited its theoretical and practical usefulness. These are addressed here through a three-version process of concept rebuilding that is subsequently applied to the human–machine knowledge relationship.

4.3.1. The General Intellect as Human Knowledge Embedded in the Machine

In the Marxist tradition, the General Intellect originates with Karl Marx’s thought piece ‘The Fragment on Machines’, in which he speculated about the relationship between the worker and the self-acting machine in a future world in which the main human input would be the organization and knowledge invested in the machine [113]. The speculation continued to consider a world in which production would be led by technologies created and maintained by human knowledge and that the nature of the knowledge locked inside the machine would be increasingly social since it comes from the head of the worker and could be shared. This version of the General Intellect was subsequently seen to embody a socialized logic that would automatically lead to the overthrow of capitalism [114]. While intriguing, Marx’s revolutionary thesis has not been historically proven due to technological determinist interpretations that have underestimating relentless capitalist technological and political innovation with the private appropriation of human intellectual labor. Nevertheless, his thought experiment remains a foundational version to which we will return.

4.3.2. The General Intellect as Shared Societal Consciousness

The negation of the technologically determinist version came in the form of post-Operaismo readings [115,116,117], emphasizing the development of collective human cognitive capacities as shared social, political, and ethical dispositions as a basis for societal transformation. In terms of categories of labor, these interpretations of the General Intellect have focused on ‘living labor’ of social consciousness and activity, compared with Marx’s original concept of ‘dead labor’ embedded in the machine.

While this anti-determinist societal version is also valuable, it risks becoming detached from the world of production, producing a challenge that must be resolved in relation to specialist techno-economic activity. An additional twist in the debate is found in the work of Wark [118], who has proposed that in 21st century society there is not a single general intellect, but multiple variants concerned with different aspects of societal complexity. This argument has supported the idea of a specific Technological General Intellect in the field of GenAI that acts as a cultural ‘glue’ for different groups of technological organic intellectuals.

4.3.3. The Organic Intellect—Combining Horizontal and Vertical Thinking and Knowledge

In response to the perceived limitations of these versions (technological determinism and potential economic detachment), an extended concept of the ‘Organic Intellect’ is proposed. This is allied to the Gramscian concept of organic intellectuals, in which these key ‘organizers’ need to develop a combined intellect—shared general political, social, and now ecological consciousness (the technological general intellect) and specialist knowledge and skills to transform the world of new forms of technology and production.

The role of vertically organized technological specialist knowledge and skill is particularly important when considering counter-hegemonic activity by tech workers as GenAI producers and key LLM users in areas such as medicine or education. These groups can generate ‘progressive’ specialist knowledge, informed by the shared general intellect, creating a progressive vertical dynamic referred to as ‘connective specialization’ that seeks to connect with other specialisms rather than residing in knowledge silos.

The dynamic relationship between the horizontal socialized general intellect and progressive vertical specialist thinking and activity is essentially dialectical. The horizontal general intellect provides the ethico-political compass for specialist activity, whereas ‘progressive’ specialist knowledge deepens the capacities of the shared General Intellect—a relationship that leads to the concept of the Organic Intellect [119].

4.3.4. Technological Organic Intellect and Machine Intelligence Relationships

The Organic Intellect, due to its reciprocal combinations of general social consciousness and specialist knowledge, is better able to undertake a progressive dialog with the machine than a single dimension. In the new dialectic, the horizontal dimension of the Organic Intellect sees shared human consciousness operating as intent to shape the social purposes of GenAI, while the vertical dimension increases levels of specialist technological knowledge to assist with both designing the architectures of GenAI and responding to machine outputs through, for example, advanced forms of prompt and context engineering [120].

Moreover, as with Wark’s idea of multiple General Intellects [118], there is not a single Organic Intellect. Arguably, more variants still could emerge due to the inter-relationships of a diversity of horizontal general intellects and numerous forms of vertical knowledge. The Organic Intellect in the case of GenAI can thus be understood as the ‘Technological Organic Intellect’.

The dialectical unity of the interaction between the human Organic Intellect and Machine Intelligence becomes manifested as a composite social, cognitive and technological unit [77]. This third unified approach has also been articulated in the work of Guile—General Intellect in the Digital Age [121], in which he suggests the unity of human and machine forms of labor—‘living-learning labor + machine-learning labor + living-learning-machine-learning labor’.

Guile’s additionality explanation helps the return to Marx’s thought experiment in the ‘Fragment’ and the idea of embedded human social knowledge in the machine. The generative capacities of GenAI progress beyond embedding because of the dialectic human and machine actions. Assisted by the technological organic intellect (social consciousness + forms of specialist knowledge), the human–machine relationship can produce what has been referred to generally as ‘hybrid intelligence’ [122], or ‘fusion knowledge’ in specific fields [123]. This dynamic can produce something more than us as it combines socialized human intentionality with the capability of the machine to generate content through the almost instantaneous computation of vast amounts of data.

But with a more ambitious dialectical concept comes political and epistemological challenges, leading to three pressing challenges. The first is how to develop the Organic Intellects of the producer group working within tech companies under the conditions of Platform Capitalist hegemony. Any advances here will require support from political, cultural and technological developments in civil society to create an influential progressive culture [124].

The second relates to ways of increasing levels of technological expertise in user groups—both specialist users, as in medicine and education, and citizen users—to best harness the powers of GenAI for social purposes.

The third, and possibly an answer to the first two challenges, concerns the reciprocal roles of technological organic intellectuals, in which an extended and unified Organic Intellect can only be meaningfully exercised by alliances of producer/user groups rather than being embodied in a single entity.

4.4. Alliances of Technological Organic Intellectuals to Connect the Alternative Sub-Bloc

Gramsci was insistent that to effectively exercise counter hegemony, the subordinate historical bloc, comprising the working class and its allies, needed to develop its own organic intellectuals to guide new forms of productive activity and to build the progressive historical bloc [24]. One hundred years later, the era of GenAI in the context of Platform Capitalism 2.0, suggests a need for a diverse range of technological organic intellectuals—digital activists, technological producers, key users, and citizens—working collaboratively across the layers of the alternative sub-bloc.

- Digital activist communities, radical researcher/writing communities, and progressive political parties—Guglielmo’s groups of radical technological activists who pioneer alternative digital ideas and practices, approximating his ‘digital commons’. This is the broad grouping that could play a cohering role across the bloc.

- Technological producer communities—these include the development of progressive specialists within tech firms who challenge corporate logics and promote socially responsible AI development [13,55]. This is the group at the heart of the machine and arguably the one that is the most difficult to develop. This is not only because of company power, but also due to the challenges of combining specialist and progressive general thinking in the form of the ‘technological organic intellect’.

- Specialist user/customizer communities—this very important diverse group comprising expert public and private sector actors, notably in higher education, healthcare, and governance, who customize and deploy GenAI applications to build layers of progressive mediation, thus helping to bridge the gap between the producers and citizens.

- Digital citizens—while most members of the public presently have unmediated relationships with GenAI and learn experientially without external support [125], groups such as communities of practice, can be assisted to engage creatively with GenAI tools through accessible forms of education [126].

Guglielmo [37], sees these ‘digital organic intellectuals’ as agents of counter-hegemonic transformation who map the ideological terrain of digital capitalism, orient strategic direction toward platform socialism through alternative imaginaries, build tools and practices that challenge algorithmic control, and forge alliances between grassroots movements, digital activists, and progressive political parties to form ‘the Digital Princess’ (a 21st century AI focused political party version of Gramsci’s Modern Prince).

While his ‘digital princess’ concept constitutes an important part of the strategy of transitioning, the idea of creating an alternative GenAI system/bloc capable of successfully contesting the Platform Capitalist bloc suggests the need for collaborative working both horizontally and vertically. Horizontal collaboration would involve a broad formation of technological organic intellectuals, in which digital activists and radical political parties are joined by specialist producer groups in tech companies and in alternative tech networks, specialist user groups such as in medicine, and citizen users.

But these diverse groups will also need to work ‘vertically’, both collaborating with and challenging national and transnational regulatory regimes. The key idea of a twin strategy—working horizontally across civil society to open spaces of innovation and working vertically within the state to confront the power relations of Big Tech—is to build reciprocal layers of progressive mediation required for transitioning away from Platform Capitalism 2.0.

4.5. Distributed Ethical Responsibilities and Trust Building

Advancements in LLM capabilities and increasing rates of application, together with the strategic idea of socialized GenAI and federated organization, point to the formation of complex multiple producer/user communities. While Platform Capitalism produces ‘closed’ producer/user technological ecosystems with the prime aim of driving up market share and profit [13,17], a socialized approach would suggest the formation of ‘open inclusive ecosystems’ of different communities with a distribution of ethical responsibilities.

While producers bear the foundational responsibility for the model’s architecture and potential for bias [127,128], and are the focus of regulatory regimes [129], ethical responsibilities become distributed as LLMs are applied across diverse settings, encompassing a complex ecosystem of stakeholders, including technological producer communities who design the LLMs; expert user/adaptor communities who customize them for specific fields like medicine; digital activist communities who promote alternative ideas and practices; and citizen-based general users who promote responsible everyday usage. By distributing the focus across all these groups, ethical responsibility becomes more comprehensive and robust than a regulatory approach aimed at a single entity.

With this distribution of production, usage, and cognition, a key issue becomes trust building through a culture of transparency about the role of the machine and how its contributions to knowledge production are understood and made known. Therefore, integral to new types of human/machine intellectual collaborations, is a process of ‘relational attribution’ where the related roles of human and artificial intelligence in knowledge production are explained [130].

The development of a diversity of producer/user communities involved in HI/AI knowledge hybridization, however, requires an enhanced transparency framework of types of ‘explanation’. A notable example is a model of ‘interpretability, explainability, and trustability’ [131], developed in relation to AI and clinical practice and adapted here to meet the more general HI-MI transparency challenge.

- Interpretability—elucidation of the ethical framing and key problems given to the LLM, shedding light on the initial intent of human input.

- Explainability—response interpretation that involves explaining how the main responses of the LLM have been interpreted to make sense of AI’s outputs in relation to the input prompts.

- Trustability—building confidence in hybridized outcomes by making clear respective human and machine contributions.

This adapted three-stage model, moving between different AI-related communities, suggests alliance-building in which each group must increase its intellectual and explanative capacities to utilize the GenAI for the common good. It is through this collaborative process that the ‘black boxes’ of GenAI are turned into ‘white boxes’ of enhanced understanding and trust to address the paradox [132].

5. Conclusions—Passive Revolution or Progressive Strategic Steps?

In exploring the envisioning and development of progressive systems, there is an inherent risk of idealism, particularly where emphasis is placed on the system’s innovative features while paying insufficient attention to the structural and political constraints that can impede its realization. We thus need to return to the recomposed question in Figure 3—What are the main challenges in transitioning to a socialized system of GenAI? By way of a general response, this final section invokes Gramsci’s famous dictum, ‘pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will’ [133], a phrase that encapsulates the need for a rigorous and cautious analysis of the prevailing balance of forces within the ongoing dialectic between hegemonies and counter-hegemonies.

5.1. Passive Revolution Effects

In the early parts of the article, reference was made to the role of regressive organic intellectuals and the domination effects of the Platform Capitalist sub-bloc that inhibit the strategic development of socialized systems. Alternative ideas and practices can emerge in radical civil society but remain small-scale. Conversely, policies can emerge in the vertical assemblage but be restrictive in scope. As a result, these limiting effects produce processes of ‘passive revolution’ whereby the dominant system gradually adapts to retain its hegemonic influence [134].

Thus far, this has been largely the case with both open-source movements and tech regulatory policy. In 2025, open-source models, while prevalent within company AI operations, have captured only about 13 percent of AI workloads [18]. At the regulatory level, questions remain as to how far policies promoted by, for example, the EU assist radical thinking and practice. Some have argued that these frameworks open spaces for alternative ideas to emerge [135], whereas others have suggested that focusing regulation primarily on managing risks associated with deployment rather than dismantling the underlying data and compute monopolies, the regulatory structure effectively legitimizes existing market concentrations [136].

A question also remains about the potential effects of Chinese GenAI innovation that, in competition with US technological hegemony, may be offering opportunities for progressive customization via open-source development. Thus far it would appear that the Chinese model complicates globalized GenAI development rather than offering a fully socialized trajectory of development.

5.2. Multiple Transitioning and Pressures of Compressed Technological Time

Passive revolution effects are compounded by transitioning complexities involving multiple systemic shifts across economic, social, political, cultural, ideological, ecological, and technological dimensions [137]. These transition dimensions broadly correspond to layers of an emerging counter-hegemonic technological sub-bloc that evolve on different timescales, thus creating tensions and asymmetries both in the sub-bloc and in the transitioning process.

A key difficulty lies in the phenomenon of ‘compressed technological time’, in which the pace of LLM development—intensifying innovation cycles, market competition, geopolitical pressures, and now the proliferation of LLM-based applications and autonomous agents—accelerates, disorients, and disrupts [138]. In contrast, ideological, and cultural transitions—the development of democratic norms, ethical standards, and ecological consciousness—require longer periods of contestation, deliberation, and consensus-building [139]. These temporal mismatches risk allowing rapidly evolving GenAI systems to outpace the societal mechanisms designed to regulate and embed them in a socialized model, therefore highlighting the strategic imperative to calibrate the relationship between these transitions.

5.3. Radical Civil Society and Building Reciprocal Layers of Progressive Mediation

Given these complexities and uneven developments, it is vital to cultivate and preserve radical imaginaries that serve both as maps of the current terrain and compasses for future direction. Scholars such as Morozov [140,141], and Guglielmo [37], have emphasized the role of digital resistance and policy advocacy in challenging platform hegemony that will include lobbying for antitrust regulation, data sovereignty, and the framing of GenAI as a public utility, while grassroots innovation through decentralized, open-source, and community-driven GenAI initiatives, can begin to construct the material and cultural infrastructure of a counter-hegemonic technological sub-bloc.

Nevertheless, emergent initiatives in radical civil society, while very important, may prove insufficient in alternative bloc building, that requires a strategy of horizontal and vertical innovation and reforms working synergistically. This can be conceptualized as ‘strong mediation’—the building of reciprocal layers of progressive activity and system development, including educational courses in universities, enterprise-based tech innovation, regional economic coordination, and national and transnational regulation. Linking these layers will be a critical mission of alliances of technological organic intellectuals.

This ecosystemic type of development of an integrated socialized system of GenAI needs to be viewed as a challenging ‘long haul’, corresponding to Guglielmo’s technological ‘war of position’, requiring realistic intermediate milestones of new techno-economic, social, political, cultural, and ecological settlements [142]. Each of these stages will also constitute recomposed problem spaces, shaped by evolving contradictions, contextual influences, and strategic interventions [68].

5.4. Next Research and Development Steps

The main aim of this review article has been to build a conceptual framework of a socialized system of GenAI and, through these structural strategies, to identify steps to resolve the GenAI paradox. However, the article itself contains a paradox—its conceptual focus reveals practical absences. Put another way, elements of the emergent progressive framework need to be tested in practice through the development of modest steps.

Here, upcoming research and development steps will focus on two related areas. The first recognizes the importance of building layers of progressive mediation in relation to the burgeoning layer of LLM applications, including processes of LLM customization, creating institutional guidelines, educative support programs, and building intellectual alliances. In this way, resolving the GenAI paradox becomes an integral part of the broader step-by-step transitioning strategy, where each phase of technological development is accompanied by building mediating layers to calibrate the temporal terrain.

Second, and more specifically related to author activity, recent research has highlighted the relatively weakly mediated relationships between LLMs and users in the field of higher education research and teaching—teachers simply acquiring LLM-related knowledge experientially [125]. Therefore, constructing a socialized system requires not only interventions in the internal architecture of GenAI, but also relation to the application layer in education.

In response to this challenge, an LLM Development Program at Capital Normal University, Beijing, in November 2025 is designed to serve as a recomposed research and development problem space to explore the possibilities and paradoxes of LLMs in the field of higher education and research in the Chinese context.

The Development Program will attempt to:

- develop ethically responsible knowledge and skills in the use and development of LLMs in the fields of research and teaching,

- harness the practical and cultural knowledge of participants to inform LLM program design and delivery in the Chinese context,

- construct an educative layer of progressive mediation at the institutional level,

- build interdisciplinary alliances among technology specialists, educators, and students,

- develop scalable good practices for LLM customization across the university and cultivate a new generation of technological organic intellectuals equipped to navigate the complexities of GenAI transformation.

The CNU Program can thus be seen as a step in building an institutional microcosm of a newly envisaged socialized system of generative artificial intelligence.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Glossary

This Glossary contains Gramscian and neo-Gramscian terms and definitions used within the article. Of a total of 14 key concepts, eight are new and experimental and can be sourced at the website—Ken Spours 2025—https://www.kenspours.com (accessed on 10 September 2025).

| Combinations of coercion and consent used by a dominant force to exercise power and influence over a subaltern force [24]. |

| A dynamic alliance of social forces unified by a shared hegemonic project, in which economic base and cultural-political superstructure are organically linked to produce and sustain a particular social order [24]. |

| A section of the historical bloc (e.g., new technologies) that play a leading role to reconstitute the overall bloc formation [25]. |

| The locations within the 45-degree zone of mediation that the dominant and alternative blocs interact and compete most intensively [25]. |

| Structured layering of hierarchical relations—governmental state and transnational institutions—that represent the vertical dimension of the dominant historical bloc [25]. |

| Connective horizontal relations—national and international—that represent the civil society dimension of the alternative historical bloc [25]. |

| A metaphor for a revolutionary political party that acts as a collective intellectual and moral leader, capable of forging national-popular will and transforming society through strategic hegemony. The party as an organism reflecting a future society marked a break with Leninism and the vanguard party [24]. |

| Thinkers and organizers who play a transformative role by linking lived realities to broader ideological and political struggles through the construction of counter-hegemony [24]. |

| A process of progressive facilitation by organic intellectuals that bridges horizontal civil society and vertical institutions, enabling mutual transformation through counter-hegemonic strategies [25]. |

| Shared social thinking that is collectively produced within society—rooted in language, cooperation, and technological mediation—that transcend individual minds and enable the formation of common understanding, creativity, and transformative potential [116]. |

| A fusion of Marx’s general intellect and Gramsci’s organic intellectual, as a socially embedded and structurally aware intelligence that integrates horizontal civil society knowledge with vertical specialized scientific understanding to produce transformative 45° knowledge aimed at reshaping both society and the world of production [25]. |

| A multi-layered framework of ‘transitioning times’ that integrates historicism, ecological urgency, and medium range ‘new settlements’ to enable purposeful living, democratic renewal, and sustainable futures [25]. |

| A multi-layered, synergistic framework and strategy that integrates political, social, economic, cultural and ecological sub-systems to support new modes of working, living, and learning, thus enabling and the formation of a sustainable historical bloc and progressive transitioning [25]. |

| A process by which dominant powers absorb and neutralize transformative ideas or movements through limited reforms, preserving their hegemony without fundamental structural change [24]. |

References

- Abbate, J. Inventing the Internet; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nordhaus, W.D. Are We Approaching an Economic Singularity? Affluence and the Acceleration of Technical Change. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, 21556. 2015. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w21556 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. ‘Deep learning’. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Yan, C.; Li, Q.; Peng, X. From Large Language Models to Large Multimodal Models: A Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI). Artificial Intelligence Index Report Stanford University. 2025. Available online: https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Ye, J. China’s AI ‘War of a Hundred Models’ Heads for a Shakeout, Reuters, 22 September 2023. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/technology/chinas-ai-war-hundred-models-heads-shakeout-2023-09-21/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Global Times. China’s Open-Source AI Models Narrow Gap with Global Proprietary Rivals: Survey. 2025. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202509/1342329.shtml (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- García-Herrero, A.; Krystyanczuk, M. How Does China Conduct Industrial Policy: Analyzing Words Versus Deeds. J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2024, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. AI Geopolitics and Data Centres in the Age of Technological Rivalry World Economic Forum, 1 July 2025. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/07/ai-geopolitics-data-centres-technological-rivalry/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Morozov, E. The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom; PublicAffairs: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zuboff, S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power; PublicAffairs: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Srnicek, N. Platform Capitalism; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijck, J.; Poell, T.; de Waal, M. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Digital Age; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, J. Paradoxes of Generative AI: Both Promise and Threat to Academic Freedom. J. Acad. Freedom 2024, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bubeck, S.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Eldan, R.; Gehrke, J.; Horvitz, E.; Kamar, F.; Lee, P.; Liu, Y.; Nori, H.; Petro, N.; et al. Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.12712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menlo Ventures. 2025 Mid-Year LLM Market Update: Foundation Model Landscape + Economics. 2025. Available online: https://menlovc.com/perspective/2025-mid-year-llm-market-update/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B.; Russell, C. Do large language models have a legal duty to tell the truth? R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 240197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Wang, Y.; Fu, C.; Xiao, Y.; Li, S.; Deng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, Z.; Li, P.; et al. Risk Taxonomy, Mitigation, and Assessment Benchmarks of Large Language Model Systems. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D. The Simple Macroeconomics of AI. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2024. Available online: https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2024-04/The%20Simple%20Macroeconomics%20of%20AI.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Eloundou, T.; Manning, S.; Mishkin, P.; Rock, D. GPTs are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.10130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M. Capitalism, Complexity, and Polycrisis: Towards Neo-Gramscian Polycrisis Analysis. Glob. Sustain. 2025, 8, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramsci, A. Selections from the Prison Notebooks; Hoare, Q., Smith, G.N., Eds. and Translators; International Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Spours, K. Neo-Gramscian Thinking for 21st-Century Progressive Politics. 2025. Available online: https://www.kenspours.com (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Anderson, P. The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci. New Left Rev. 1976, I, 5–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showstack-Sassoon, A. Gramsci’s Politics: A Study in Hegemony and Political Theory; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P. The Gramscian Moment: Philosophy, Hegemony and Marxism; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, P. Neo-Gramscianism and the International Political Economy. Cap. Cl. 1991, 45, 119–129. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, B. Anatomy of the Neoliberal State. New Left Rev. 1997, I/225, 5–39. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, A.D. Unravelling Gramsci: Hegemony and Passive Revolution in the Global Political Economy; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, D.L.; Egan, D. A Neo-Gramscian Approach to Corporate Political Strategy: Conflict and Accommodation in the Climate Change Negotiations. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 803–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, W. Fossil Capitalism, Climate Capitalism, Energy Democracy: The Struggle for Hegemony in an Era of Climate Crisis. Social. Stud. 2020, 14, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, A. Just Transition as a Gramscian War of Position: Strategies for Climate Justice in the American Context. Capital. Nat. Social. 2020, 31, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Timcke, S. Algorithms and the End of Politics: How Technology Shapes 21st-Century American Life; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shad, K.B. Algorithmic Hegemony: AI, Political Elites, and the Reinvention of Electoral Influence. J. Sociocybernetics 2025, 20, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielamo, M. The Left and Digital Politics. Political Parties from Platform Neoliberalism to Platform Socialism; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Couldry, N.; Mejias, U.A. The Costs of Connection: How Data is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating it for Capitalism; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wessel, M.; Adam, M.; Benlian, A.; Majchrzak, A.; Thies, F. Generative AI and its Transformative Value for Digital Platforms. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2025, 42, 346–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothman, D. Gramsci’s Historical Bloc: Structure, Hegemony and Dialectical Interactions. In Reading Gramsci Today: A New Political Practice; Leal, T.D.R., da Cunha, A.T., de Morais, M.P.C.T., Eds.; Editora UFRJ: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018; pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiris, P. The historical bloc as a strategic node in Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks. Int. Gramsci J. 2019, 3, 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, A.; Williams, R. Platform Power: The New Hegemony of Digital Capitalism; Verso: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fretigne, J.Y. To Live Is to Resist: The Life of Antonio Gramsci; Marris, L., Translator; University of Chicago Press: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, P.; Leyshon, A. Platform capitalism: The intermediation and capitalization of digital economic circulation. Financ. Soc. 2017, 3, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitropoulos, E. Platform Capitalism, Platform Cooperativism, and the Commons. Rethink. Marx. 2021, 33, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, P.; Biderman, S.; Gao, L.; Thoppilan, R.; Leahy, C. Will we run out of data? Limits of LLM scaling based on human-generated data. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.04325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varoufakis, Y. Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism; Verso: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J.S. The Business Ethics of Elon Musk, Tesla, Twitter and the Tech Industry. Harvard Law Today. 2023. Available online: https://hls.harvard.edu/today/the-business-ethics-of-elon-musk-tesla-twitter-and-the-tech-industry/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Hall, S.; O’Shea, A. Common-sense neoliberalism. Soundings 2013, 55, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goatley, A. The Ideological Power of AI: How LLMs Shape Our Worldview. 2025. Available online: https://www.techpolicy.press/the-ideological-power-of-ai-how-llms-shape-our-worldview/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution; Portfolio Penguin: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Avis, J. Socio-technical imaginary of the fourth industrial revolution and its implications for vocational education and training: A literature review. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2018, 70, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avis, J. Thinking about the future: The fourth industrial revolution, capitalism, waged labour and anti-work. In The SAGE Handbook of Learning and Work; Malloch, M., O’Connor, B.N., Evans, K., Cairns, L., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2023; pp. 497–511. [Google Scholar]

- Carrigan, M.; Fatsis, L. The Public and Their Platforms: Public Sociology in an Era of Social Media; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zagzebski, L.T. Introduction. In Epistemic Authority: A Theory of Trust, Authority, and Autonomy in Belief; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]