Analysis of the Effects of CSR and Compliance Programs on Organizational Reputation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility

2.2. Compliance Programs

2.3. Reputational Risk Management

2.4. The Corporate Image

2.5. The Relationship Between CSR and Compliance Programs

2.6. CSR and Its Link to Reputational Risk Management

2.7. CSR and Its Link with Corporate Image

2.8. The Relationship Between Reputational Risk Management and Compliance Programs

2.9. The Effects of Compliance Programs on Corporate Image

2.10. Reputational Risk Management and Its Effects on Corporate Image

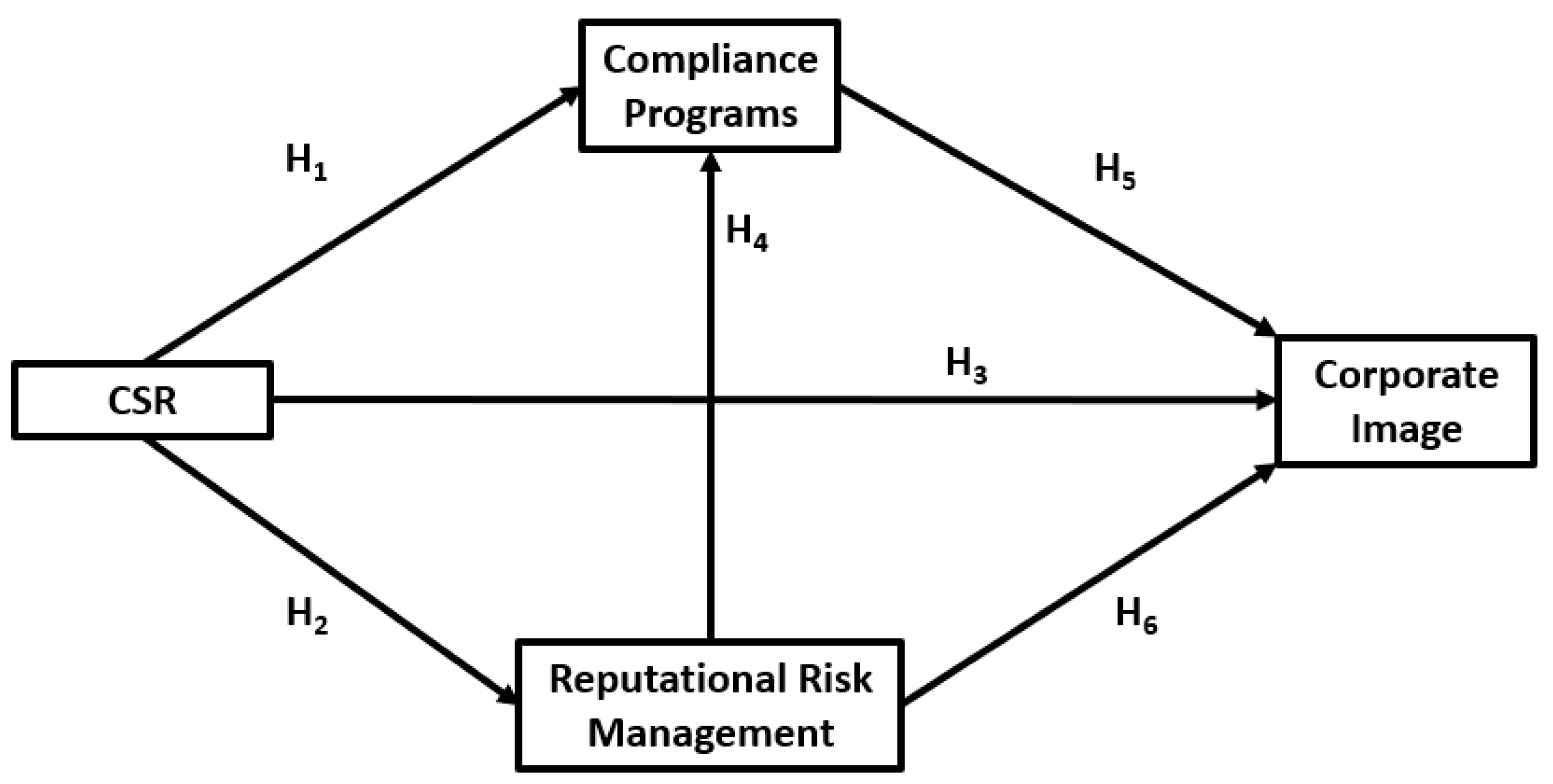

3. Research Model

4. Methodology

4.1. Population and Sample

4.2. Measures

4.3. Control Variables

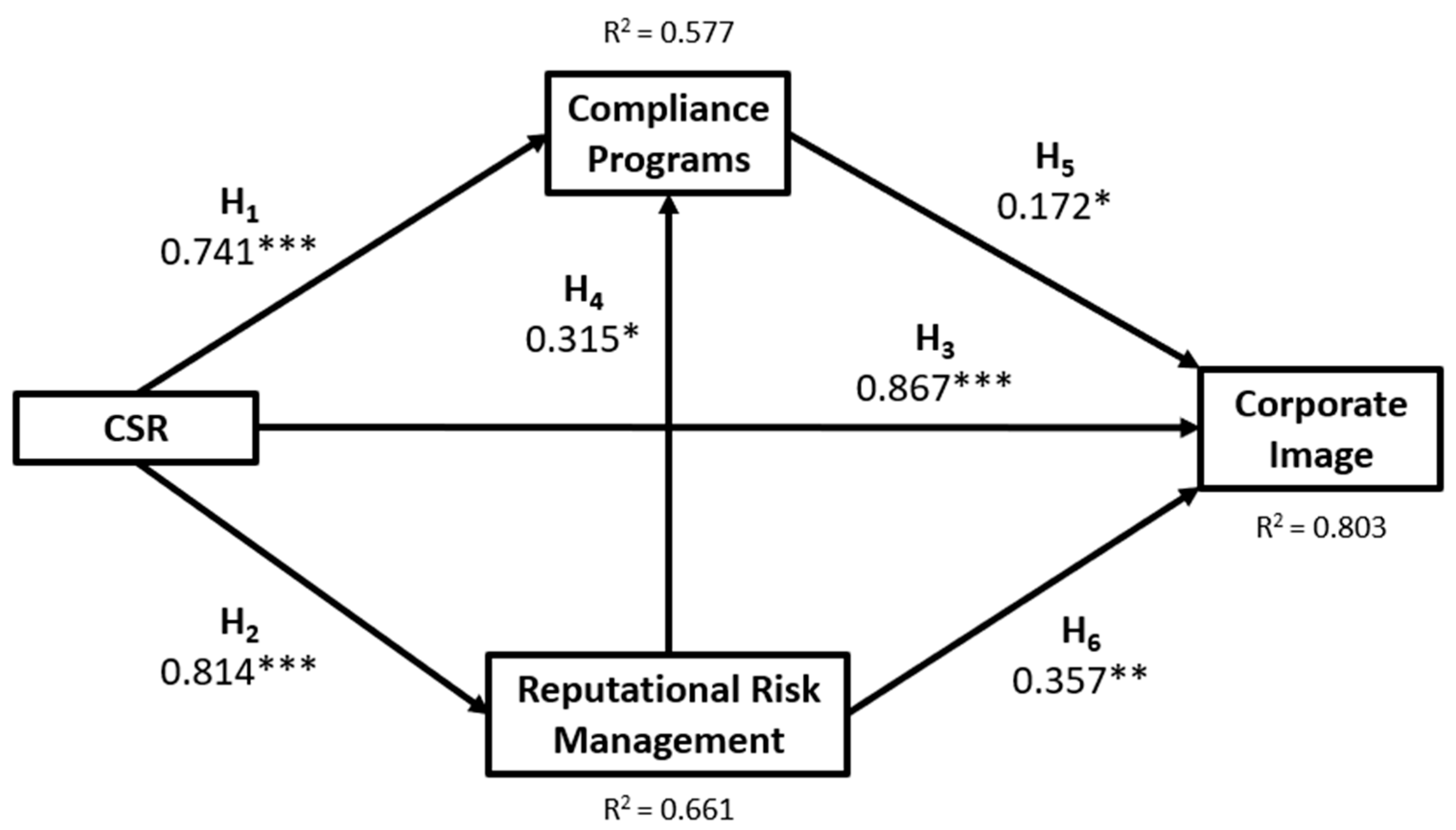

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| ML | Money Laundering |

| TF | Terrorist Financing |

| NGOs | Non-Governmental Organizations |

| HR | Human Resources |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

References

- Atkins, M. Should banks face criminal prosecution for breaches of Money Laundering Regulations or are civil fines effective. Analysis of the significance of the first ever criminal conviction of a bank (NatWest) for breaches of the Money Laundering Regulations. J. Econ. Criminol. 2024, 6, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, T.K.; Cahaya, F.R.; Joseph, C. Coercive Pressures and Anti-corruption Reporting: The Case of ASEAN Countries. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, N.I.; Wan Ismail, W.K. The impact of corporate social responsibility on corporate image in the construction industry: A case of SMEs in Egypt. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2022, 12, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira Pena, A.M. La efectividad de los criminal compliance programs como objeto de prueba en el proceso penal. Política Crim. 2016, 11, 467–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa-Rojas, L.M. El lavado de activos en la economía formal colombiana: Aproximaciones sobre el impacto en el PIB departamental. Rev. Crim. 2011, 53, 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Vittori, J. Terrorist Financing and Resourcing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Quintero, H.A. La Eficacia de las Normas de Prevención, Detección y Sanción del Lavado de Activos en Colombia; Ediciones Unibagué: Ibagué, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt, K.; Gironda, A.; Lugo, J.; Oyola, W.; Uzcátegui, R. Empresas Mineras y Población: Estrategias de Comunicación y Relacionamiento; Universidad ESAN: Lima, Peru, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.-H.; Yu, J.-E.; Choi, M.-G.; Shin, J.-I. The effects of CSR on customer satisfaction and loyalty in China: The moderating role of corporate image. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Ganzo, E. La responsabilidad social corporativa: Su dimensión normativa: Implicaciones para empresas españolas. Pecunia Rev. Fac. Cienc. Económicas Empres. 2006, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawski, T. CSR in American banking sector. Copernic. J. Financ. Account. 2018, 7, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Lynch, R.; Melewar, T.C.; Jin, Z. The moderating influences on the relationship of corporate reputation with its antecedents and consequences: A meta-analytic review. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, E.D. Criminal Enterprises and Governance in Latin America and the Caribbean; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dammert, L.; Sarmiento, K. Corruption, organized crime, and regional governments in Peru. In Corruption in Latin America: How politicians and Corporations Steal from Citizens; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 179–204. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, L. Corporate social responsibility. A strategy for social and territorial sustainability. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2022, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.A.; Russell, D.W.; Honea, H. Corporate Social Responsibility Failures: How do Consumers Respond to Corporate Violations of Implied Social Contracts? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidu, A.; Haron, M.; Amran, A. Corporate social responsibility: A review on definitions, core characteristics and theoretical perspectives. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Searcy, C. Zeitgeist or chameleon? A quantitative analysis of CSR definitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setó-Pamies, D.; Papaoikonomou, E. A Multi-level Perspective for the Integration of Ethics, Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability (ECSRS) in Management Education. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, R.; Freeman, R.E.; Hockerts, K. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Scandinavia: An Overview. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. How does corporate social responsibility benefit firms? Evidence from Australia. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2010, 22, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Ruiz, A.; García de los Salmones, M.d.M.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I.A. Las Dimensiones de la Responsabilidad Social de las Empresas Como Determinantes de las Intenciones de Comportamiento del Consumidor; Asociación Asturiana de Estudios Económicos: Oviedo, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, R. How do stakeholder pressure influence on CSR-Practices in Poland? The construction industry case. J. EU Res. Bus. 2019, 2019, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, W.; Hidayat, J.; Ramli, N.R.A.; Syam, S.A.N.; Salsabilah, D. Sustainability in Business: Integrating CSR into Long-term Strategy. Adv. Bus. Ind. Mark. Res. 2024, 2, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiao, S.; Ma, C. The impact of ESG responsibility performance on corporate resilience. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 93, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-Gault, D.; Castillo, A. The Promises and Perils of Compliance: Organizational Factors in the Success (or Failure) of Compliance Programs; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Qiao, J.; Yao, S.; Strielkowski, W.; Streimikis, J. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corruption: Implications for the Sustainable Energy Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlen, L.; Montiel, J.P.; Ortiz de Urbina Gimeno, Ì. Compliance y Teoría del Derecho Penal; Marcial Pons: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wulf, K. The Ethics and Compliance Program Manual for Multinational Organizations. In Ethics and Compliance Programs in Multinational Organizations; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 263–353. [Google Scholar]

- Orel, V.; Klymchuk, A. Anti-Corruption and Sanction Compliance as a Method of reducing Risks in the Activity of Corporate Bodies. In Proceedings of the V International Scientific Congress Society of Ambient Intelligence, Praga, Czech Republic, 17–21 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bayo, P.; Red-well, E.E. Ethical compliance and corporate reputation: A theoretical review. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 1, 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- Stucke, M.E. In search of effective ethics & compliance programs. J. Corp. L. 2013, 39, 769. [Google Scholar]

- Gutterman, A.S. Elements of Effective Compliance Programs. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4477609 (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Peng, C. Building a High-Trust Society. China Rev. 2024, 24, 107–137. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoest, K.; Redert, B.; Maggetti, M.; Levi-Faur, D.; Jordana, J. Trust and regulation. In Handbook on Trust in Public Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 360–380. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira de Araújo Lima, P.; Crema, M.; Verbano, C. Risk management in SMEs: A systematic literature review and future directions. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanz, K.-U. Reputation and Reputational Risk Management. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2006, 31, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, F.; Petersen, H.L. Teaching reputational risk management in the supply chain. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 18, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkmans, C.; Kerkhof, P.; Beukeboom, C.J. A stage to engage: Social media use and corporate reputation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, I. Reputational risks and large international banks. Financ. Mark. Portf. Manag. 2016, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatzert, N. The impact of corporate reputation and reputation damaging events on financial performance: Empirical evidence from the literature. Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.; Gallagher, R. The Valuation Implications of Enterprise Risk Management Maturity. J. Risk Insur. 2015, 82, 625–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazid, A.S.; Mkheimer, I.; Mahmud, M.S. The effect of corporate image on customer loyalty: The mediating effect of customer satisfaction. J. Res. Lepid. 2020, 51, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golgeli, K. Corporate Reputation Management: The Sample of Erciyes University. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 122, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, E.R.; Balmer, J.M.T. Managing Corporate Image and Corporate Reputation. Long Range Plan. 1998, 31, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamma, H.M. Toward a comprehensive understanding of corporate reputation: Concept, measurement and implications. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 7, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Salam, E.M.; Shawky, A.Y.; El-Nahas, T. The impact of corporate image and reputation on service quality, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty: Testing the mediating role. Case analysis in an international service company. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2013, 3, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.Y.; Danish, R.Q.; Asrar-ul-Haq, M. How corporate social responsibility boosts firm financial performance: The mediating role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.; Raposo, M. The influence of university image on student behaviour. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2010, 24, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.P. The Compliance Function: An Overview. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Law and Governance; Gordon, J.N., Ringe, W.-G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 981–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Marzá, D. From ethical codes to ethical auditing: An ethical infrastructure for social responsibility communication. Prof. Inf. 2017, 26, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. The Case for and Against Business Assumption of Social Responsibilities. Acad. Manag. J. 1973, 16, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Wasieleski, D.M. Corporate Ethics and Compliance Programs: A Report, Analysis and Critique. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Jo, H.; Na, H. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect Information Asymmetry? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 549–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, F.; Petersen, H.L. Managing Reputational Risks in Supply Chains. In Supply Chain Risk Management: Advanced Tools, Models, and Developments; Khojasteh, Y., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Eberle, D.; Berens, G.; Li, T. The Impact of Interactive Corporate Social Responsibility Communication on Corporate Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Larrinaga, C.; Moneva, J.M. Corporate social reporting and reputation risk management. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Put Reputation at Risk by Inviting Activist Targeting? An Empirical Test among European SMEs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heal, G. Corporate Social Responsibility: An Economic and Financial Framework. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2005, 30, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodie, Z. Robert C. Merton and the science of finance. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2019, 12, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Kim, H.; Woo, J. How CSR Leads to Corporate Brand Equity: Mediating Mechanisms of Corporate Brand Credibility and Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Antecedents and benefits of corporate citizenship: An investigation of French businesses. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 51, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Modified Pyramid of CSR for Corporate Image and Customer Loyalty: Focusing on the Moderating Role of the CSR Experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.A.; Nguyen, B.; Melewar, T.; Bodoh, J. Exploring the corporate image formation process. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2015, 18, 86–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enseñat de Carlos, S. Manual del Compliance Officer; Aranzadi: Cizur Menor, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mir-Puig, S.; Corcoy-Bidasolo, M.; Gómez-Martín, V. Responsabilidad de la Empresa y “Compliance”: Programas de Prevención, Detección y Reacción Penal; Edisofer: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Teraji, S. A theory of norm compliance: Punishment and reputation. J. Socio-Econ. 2013, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B. Organizational Culture: A Framework and Strategies for Facilitating Employee Whistleblowing. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2004, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushkat, R. State Reputation and Compliance with International Law: Looking through a Chinese Lens. Chin. J. Int. Law 2011, 10, 703–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deciu, V. The Organizations’ Psychological Environment Traits Modification When Adopting an Ethics and Compliance Program. Psychology 2022, 12, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N.A.; Barnett, M.L. Opportunity Platforms and Safety Nets: Corporate Citizenship and Reputational Risk; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Njinyah, S.; Asongu, S.; Adeleye, N. The interaction effect of government non-financial support and firm’s regulatory compliance on firm innovativeness in Sub-Saharan Africa. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, C. Do firms benefit from electing a voluntary approach to environmental compliance? In Proceedings of the 1995 IEEE International Symposium on Electronics and the Environment ISEE (Cat. No.95CH35718), Orlando, FL, USA, 1–3 May 1995; pp. 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fraguío, M.P.D.; Macías, M.I.C. Gerencia de Riesgos Sostenibles y Responsabilidad Social Empresarial en la Entidad Aseguradora; Fundación Mapfre: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, R.; Trequattrini, R.; Cuozzo, B.; Cano-Rubio, M. Corporate corruption prevention, sustainable governance and legislation: First exploratory evidence from the Italian scenario. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 217, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiana, P.A. Stakeholder Engagement in Sustainability Reporting: Evidence of Reputation Risk Management in Large Australian Companies. Aust. Account. Rev. 2019, 29, 726–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, R.W. El riesgo reputacional y su impacto en las inversiones. Rev. Fasecolda 2020, 179, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, L.; Cui, X.; Nazir, R.; Binh An, N. How do CSR and perceived ethics enhance corporate reputation and product innovativeness? Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 5131–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cornejo, C.; de Quevedo-Puente, E.; Delgado-García, J.B. How to manage corporate reputation? The effect of enterprise risk management systems and audit committees on corporate reputation. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonime-Blanc, A. Manual de Riesgo Reputacional: Sobrevivir y Prosperar en la era de la Hipertransparencia; Corporate Excellence—Centre for Reputation Leardership: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, A.T.; Weber, J.H.; Post, J.E. Business and Society: Stakeholders, Ethics, Public Policy; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA; Irwin: Burr Ridge, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H.; Na, H. Does CSR Reduce Firm Risk? Evidence from Controversial Industry Sectors. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A. Education research quantitative analysis for little respondents: Comparing of Lisrel, Tetrad, GSCA, Amos, SmartPLS, WarpPLS, and SPSS. J. Studi Guru Pembelajaran 2021, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. PLS-SEM statistical programs: A review. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2021, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Wang, Y.-M.; Wu, T.-W.; Wang, P.-A. An empirical analysis of the antecedents and performance consequences of using the moodle platform. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2013, 3, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, J.B.; Bentler, P.M. Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Psychology, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesfioui, M.; Trufin, J.; Zuyderhoff, P. Bounds on Spearman’s rho when at least one random variable is discrete. Eur. Actuar. J. 2022, 12, 321–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, M.I.; Fahmi, M.; Jufrizen; Muslih; Prayogi, M.A. The Quality of Small and Medium Enterprises Performance Using the Structural Equation Model-Part Least Square (SEM-PLS). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1477, 052052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Factor Analysis as a Tool for Survey Analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. Peerj Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common Method Bias in Marketing: Causes, Mechanisms, and Procedural Remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Park, J.; Kim, H.J. Common method bias in hospitality research: A critical review of literature and an empirical study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 56, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, D.N. The Enduring Evolution of the P Value. JAMA 2016, 315, 1113–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, F.; Wang, K.; Hou, W.; Erten, O. Identifying geochemical anomaly through spatially anisotropic singularity mapping: A case study from silver-gold deposit in Pangxidong district, SE China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2020, 210, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, G.; He, Z.; Chen, L. How to implement strategic CSR? A mechanism oriented to corporate responsible competitiveness. J Adv Manag Sci 2024, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Harrison, D.E.; Ferrell, L.; Hair, J.F. Business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sector | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Financial | 42 | 27% |

| Services | 25 | 16% |

| Others | 44 | 30% |

| Commercial | 11 | 7% |

| Construction | 10 | 6% |

| Mining | 8 | 5% |

| Industrial | 6 | 4% |

| Technology | 5 | 3% |

| Energy | 3 | 2% |

| Total | 154 | 100% |

| Sector | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Director/Compliance Officer | 93 | 60% |

| Manager/Director of CSR | 13 | 8% |

| Manager/Director of Risk Management | 13 | 8% |

| Manager/Director of Internal Audit | 10 | 6% |

| Manager/Director of Human Resources | 9 | 6% |

| Manager/Director of Marketing | 2 | 1% |

| Other (Accountants, financial managers, executive directors, corporate governance specialists, consultants, etc.) | 14 | 9% |

| Total | 154 | 100% |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | R2 | HTMT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reputational Risk Management | 0.916 | 0.924 | 0.934 | 0.673 | 0.661 | 0.879 |

| Corporate Image | 0.969 | 0.971 | 0.972 | 0.716 | 0.803 | 0.730 |

| Compliance Programs | 0.915 | 0.936 | 0.927 | 0.564 | 0.577 | 0.599 |

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | F-Square | |

|---|---|---|

| H1. CSR → Compliance Programs | 2.965 | 0.189 |

| H2. CSR → Reputational Risk Management | 1.000 | 1.965 |

| H3. CSR → Corporate Image | 2.926 | 0.639 |

| H4. Reputational Risk Management → Compliance Programs | 2.965 | 0.180 |

| H5. Compliance Programs → Corporate Image | 2.394 | 0.164 |

| H6. Reputational Risk Management → Corporate Image | 2.893 | 0.273 |

| Original Sample | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | T-Statistics | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. CSR → Compliance Programs | 0.484 | 0.650 | 0.138 | 3.519 | 0.000 |

| H2. CSR → Reputational Risk Management | 0.814 | 0.858 | 0.031 | 26.597 | 0.000 |

| H3. CSR → Corporate Image | 0.660 | 0.795 | 0.115 | 5.728 | 0.000 |

| H4. Reputational Risk Management → Compliance Programs | 0.315 | 0.150 | 0.151 | 2.085 | 0.037 |

| H5. Compliance Programs → Corporate Image | 0.172 | 0.233 | 0.082 | 2.084 | 0.037 |

| H6. Reputational Risk Management → Corporate Image | 0.411 | 0.311 | 0.112 | 3.669 | 0.000 |

| Original Sample | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | T-Statistics | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. CSR → Compliance Programs | 0.741 | 0.780 | 0.051 | 14.649 | 0.000 |

| H2. CSR → Reputational Risk Management | 0.814 | 0.858 | 0.031 | 26.597 | 0.000 |

| H3. CSR → Corporate Image | 0.867 | 0.880 | 0.022 | 40.020 | 0.000 |

| H4. Reputational Risk Management → Compliance Programs | 0.315 | 0.150 | 0.151 | 2.085 | 0.037 |

| H5. Compliance Programs → Corporate Image | 0.172 | 0.233 | 0.082 | 2.084 | 0.037 |

| H6. Reputational Risk Management → Corporate Image | 0.357 | 0.274 | 0.103 | 3.454 | 0.001 |

| Original Sample | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | T-Statistics | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE → Compliance Programs | −0.015 | −0.152 | 0.083 | 1.802 | 0.072 |

| AGE → Corporate Image | 0.018 | 0.005 | 0.051 | 0.346 | 0.729 |

| AGE → CSR | 0.124 | 0.115 | 0.134 | 0.921 | 0.357 |

| AGE → Reputational Risk Management | −0.036 | −0.033 | 0.063 | 0.575 | 0.565 |

| SIZE → Compliance Programs | 0.067 | 0.049 | 0.079 | 0.849 | 0.396 |

| SIZE → Corporate Image | −0.018 | −0.024 | 0.046 | 0.398 | 0.691 |

| SIZE → CSR | 0.143 | 0.152 | 0.114 | 1.253 | 0.210 |

| SIZE → Reputational Risk Management | −0.022 | −0.043 | 0.057 | 0.388 | 0.698 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arredondo-Méndez, V.H.; Muñoz-Molina, Y.; Para-González, L.; Mascaraque-Ramírez, C. Analysis of the Effects of CSR and Compliance Programs on Organizational Reputation. Systems 2025, 13, 905. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100905

Arredondo-Méndez VH, Muñoz-Molina Y, Para-González L, Mascaraque-Ramírez C. Analysis of the Effects of CSR and Compliance Programs on Organizational Reputation. Systems. 2025; 13(10):905. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100905

Chicago/Turabian StyleArredondo-Méndez, Víctor Hugo, Yaromir Muñoz-Molina, Lorena Para-González, and Carlos Mascaraque-Ramírez. 2025. "Analysis of the Effects of CSR and Compliance Programs on Organizational Reputation" Systems 13, no. 10: 905. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100905

APA StyleArredondo-Méndez, V. H., Muñoz-Molina, Y., Para-González, L., & Mascaraque-Ramírez, C. (2025). Analysis of the Effects of CSR and Compliance Programs on Organizational Reputation. Systems, 13(10), 905. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100905