TMT Diversity and the Financial Performance of Listed Chinese Companies: Three-Way Interaction Analysis of Innovativeness and Government R&D Subsidies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Upper Echelons Theory

2.2. Absorptive Capacity

2.3. Institutional Theory and Signaling Theory

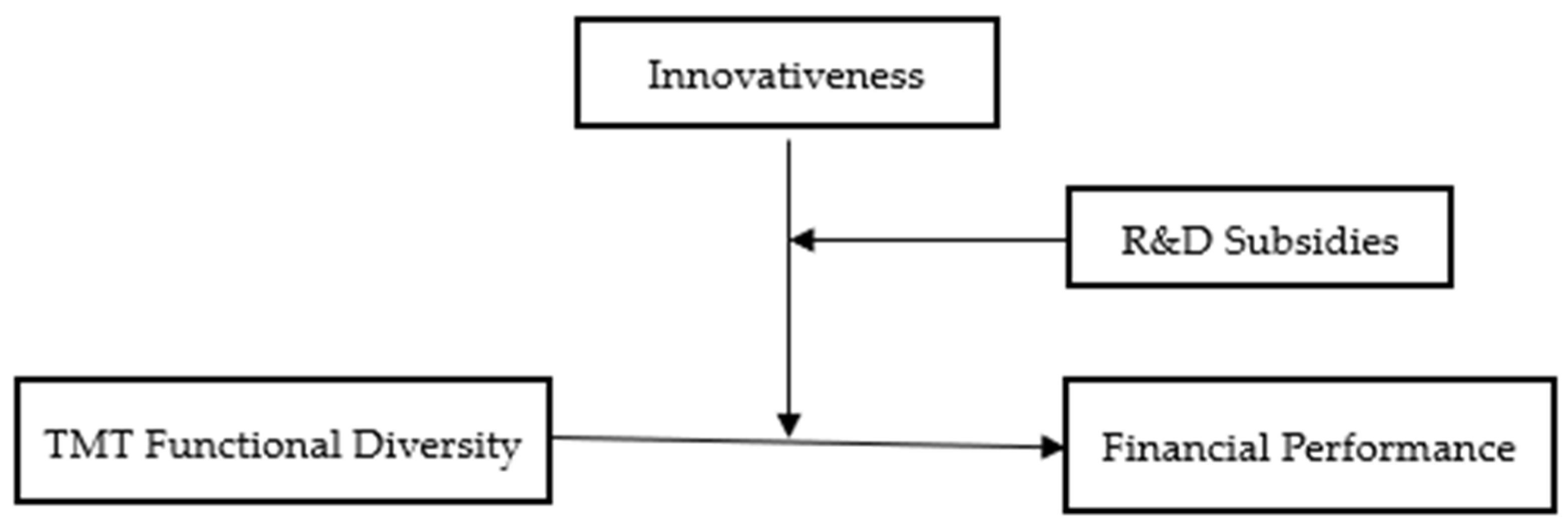

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Functional Diversity of TMTs and Financial Performance

3.2. Moderating Role of Innovativeness

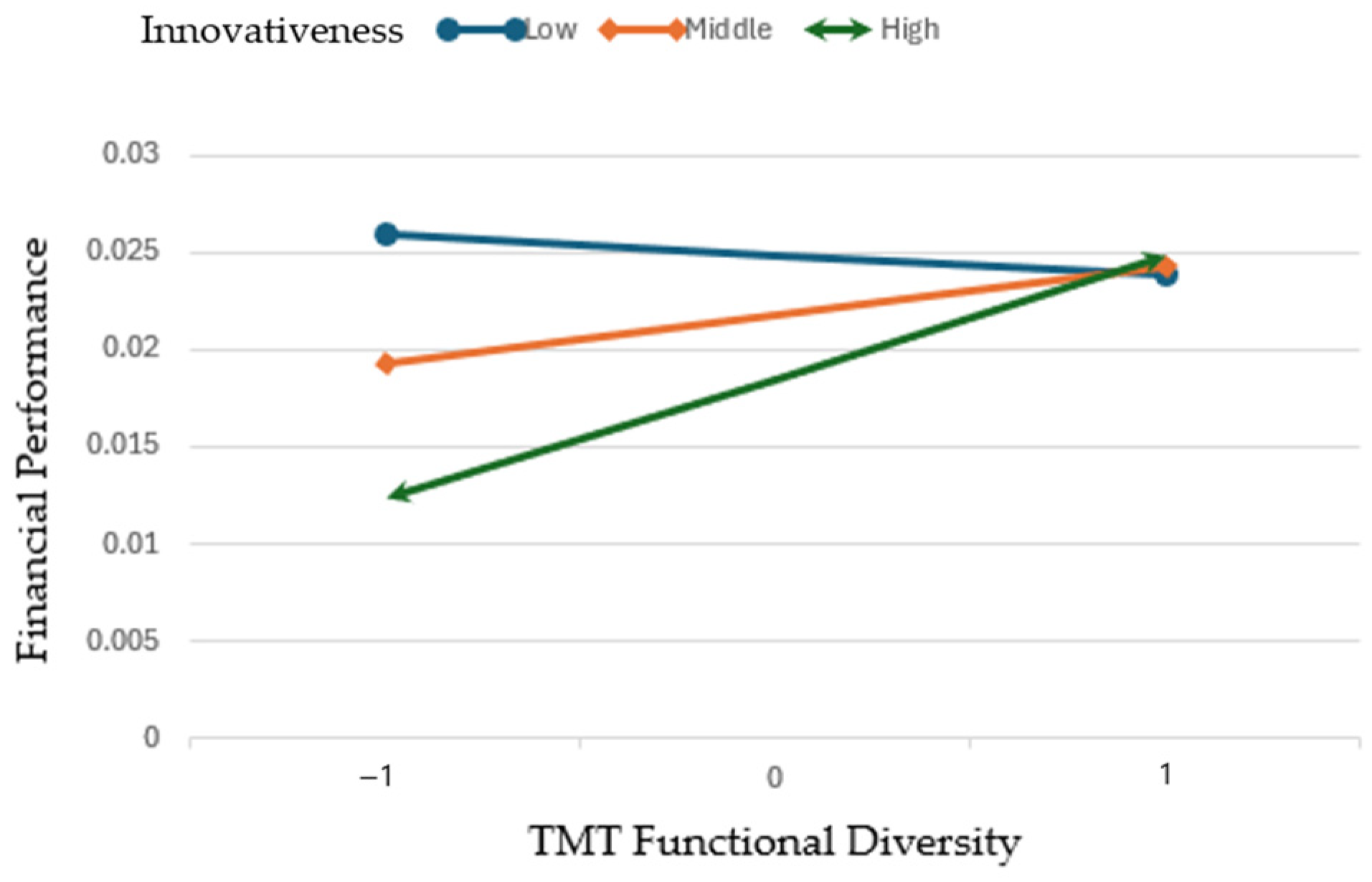

3.3. Three-Way Moderating Effect of Government R&D Subsidies

4. Research Model and Method

4.1. Data Collection and Sample

4.2. Variable Measurement

4.2.1. Independent Variable (TMT Functional Diversity)

4.2.2. Dependent Variable (Financial Performance)

4.2.3. Moderating Variable (Innovativeness)

4.2.4. Three-Way Moderator (Government R&D Subsidies)

4.2.5. Control Variables

| Type | Variable Name | Operational Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | TMT functional diversity | Degree of heterogeneity in the major functional backgrounds of TMT members, classified using profile and curriculum vitae data. Functional background is divided into eight categories: production/operations, R&D, HR, management, marketing, finance, legal, and other. | [45] |

| Dependent variable | Financial performance (ROA) | Return on total assets (net profit before taxation ÷ total assets) | [47,48] |

| Moderating variable | Innovativeness | R&D intensity = R&D investment ÷ operating income | [8,50] |

| Government R&D subsidies | Total amount of financial support provided for firms’ innovation activities, measured as the natural logarithm (Ln) of the actual subsidy amount. Subsidy items include key terms such as high-tech, innovation, patent, science, technology, research and development, talent, new product, invention, research, property rights, emerging industry, Spark plan, and Torch plan. | [51] | |

| Control variable | Firm size | Natural logarithm (Ln) of the number of full-time employees | [53] |

| Firm age | Number of years since establishment (base year minus year of foundation) | [54,55] | |

| Fixed-asset ratio | Fixed assets ÷ total assets | [56,57] | |

| TMT size | Number of TMT members | [58] |

5. Results Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

5.2. Regression Analysis

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Findings and Discussion

6.2. Implications

6.2.1. Research Implications

6.2.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEO | chief executive officer |

| CSMAR | Chinese Securities Market and Accounting Research |

| ESG | environmental, social, and governance |

| HHI | Herfindahl–Hirschman index |

| HR | human resources |

| R&D | research and development |

| ROA | return on assets |

| TMT | top management team |

| VIF | variance inflation factor |

References

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M.A.; Geletkanycz, M.A.; Sanders, W.G. Upper echelons research revisited: Antecedents, elements, and consequences of top management team composition. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 749–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Hernández, R.; Liu, P. Government intervention and corporate policies: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1205–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, P. The allocation and effectiveness of China’s R&D subsidies: Evidence from listed firms. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1774–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springut, M.; Schlaikjer, S.; Chen, D. China’s Program for Science and Technology Modernization; Centra Technology, Incorporated: Burlington, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liu, L. TMT entrepreneurial passion diversity and firm innovation performance: The mediating role of knowledge creation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 268–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Wen, Y. Top management team heterogeneity and peer effects in investment decision-making: Based on the social learning perspective. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2025, 31, 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Admin. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Li, S.; Guo, C. Top management team career experience heterogeneity, digital transformation, and the corporate green innovation: A moderated mediation analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1276812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Gao, Q.; Wang, D. The impact of top management team tenure heterogeneity on innovation efficiency of declining firms. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0313624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomareva, Y.; Uman, T.; Bodolica, V.; Wennberg, K. Cultural diversity in top management teams: Review and agenda for future research. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, N. Institutional complexity and corporate environmental investments: Evidence from China’s mixed-ownership reform of state-owned enterprises. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2024, 20, 716–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J. Exploring the role of top management team diversity and absorptive capacity in the relationship between corporate environmental, social, and governance performance and firm value. Systems 2024, 12, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, B.H., Jr.; Lovelace, J.B.; Cowen, A.P.; Hiller, N.J. Metacritiques of upper echelons theory: Verdicts and recommendations for future research. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 1029–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, F.W. The Principles of Scientific Management; Harper & Brothers Press: New York, NY, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. The compensation of executives. Sociometry 1957, 20, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromiley, P.; Rau, D. Social, behavioral, and cognitive influences on upper echelons during strategy process: A literature review. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 174–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, T.; Pelled, L.H.; Smith, K.A. Making use of difference: Diversity, debate, and decision comprehensiveness in top management teams. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersema, M.F.; Bantel, K.A. Top management team demography and corporate strategic change. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S. Top management team internationalization and firm performance: The mediating role of foreign market entry. Manag. Int. Rev. 2010, 50, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.U.; Park, J.H. Top team diversity, internationalization and the mediating effect of international alliances. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, S.; Ruigrok, W. In at the deep end of firm internationalization: Nationality diversity on top management teams matters. Manag. Int. Rev. 2013, 53, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizmaș, E.; Feder, E.S.; Maticiuc, M.D.; Vlad-Anghel, S. Team management, diversity, and performance as key influencing factors of organizational sustainable performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z. Top management team stability and corporate innovation sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Managing potential and realized absorptive capacity: How do organizational antecedents matter? Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Raynard, M. Institutional strategies in emerging markets. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2015, 9, 291–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulou, E.; Navazhylava, K. Ethnic brand identity work: Responding to authenticity tensions through celebrity endorsement in brand digital self-presentation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 974–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huang, H.; Chen, X.; Tian, F. Functional diversity of top management teams and firm performance in SMEs: A social network perspective. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2023, 17, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Li, C.; Sheldon, O.J.; Zhao, J. CEO transformational leadership and firm innovation: The role of strategic flexibility and top management team knowledge diversity. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2023, 17, 933–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunderson, J.S.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Comparing alternative conceptualizations of functional diversity in management teams: Process and performance effects. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Ge, Y.; Wang, J. Top management team intrapersonal functional diversity and adaptive firm performance: The moderating roles of the CEO–TMT power gap and severity of threat. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 772739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X. A meta-analysis of top management team heterogeneity and corporate innovation performance in China. In Proceedings of the 7th International Seminar on Education, Management and Social Sciences (ISEMSS 2023), Kunming, China, 14–16 July 2023; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 1707–1718. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Ai, J. Empirical Analysis of the Nexus Between Top Management Team Diversity and Firm Performance: A Study of Chinese Companies. 2025. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5085541 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Midavaine, J.; Smith, L.; Johnson, R. Board diversity and R&D investment: The impact of educational and gender diversity on innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 150, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, K. Government-subsidized R&D and firm innovation: Evidence from China. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, G.B.; Reinthaler, V. The effectiveness of subsidies revisited: Accounting for wage and employment effects in business R&D. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1403–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cin, B.C.; Kim, Y.J.; Vonortas, N.S. The impact of public R&D subsidy on small firm productivity: Evidence from Korean SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 48, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huergo, E.; Trenado, M.; Ubierna, A. The impact of public support on firm propensity to engage in R&D: Spanish experience. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 113, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Wang, H.; Geng, X.; Yu, Y. Rent appropriation of knowledge-based assets and firm performance when institutions are weak: A study of Chinese publicly listed firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 892–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, O.C.; Triana, M.C.; Li, M. The effects of racial diversity congruence between upper management and lower management on firm productivity. Acad. Manag. J. 2021, 64, 1355–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liao, S.; Fu, L. How TMT diversity influences open innovation: An empirical study on biopharmaceutical firms in China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 34, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M.A.; Fredrickson, J.W. Top management teams, global strategic posture, and the moderating role of uncertainty. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangena, M.; Tauringana, V.; Chamisa, E. Corporate boards, ownership structure and firm performance in an environment of severe political and economic crisis. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, S23–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.T.; Wu, Y.S. Benchmarking performance indicators for banks. Benchmarking 2006, 13, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, J.; Cloodt, M. Measuring innovative performance: Is there an advantage in using multiple indicators? Res. Policy 2003, 32, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J. Political connection, government R&D subsidies and innovation efficiency: Evidence from China. Fin. Res. Lett. 2022, 48, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, G. Collaboration networks, structural holes, and innovation: A longitudinal study. Admin. Sci. Q. 2000, 45, 425–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, D.Z.; Colovic, A.; Misganaw, B.A. Firm size, firm age and business model innovation in response to a crisis: Evidence from 12 countries. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 26, 2250054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Hu, W.; Li, S. Ambidextrous leadership and organizational innovation: The importance of knowledge search and strategic flexibility. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huergo, E.; Jaumandreu, J. How does probability of innovation change with firm age? Small Bus. Econ. 2004, 22, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C. Capital structure. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Tang, Y.I. CEO hubris and firm risk taking in China: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. Structural inertia and organizational change. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 49, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, A.; Segarra, A.; Teruel, M. Like milk or wine: Does firm performance improve with age? Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2013, 24, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger-Helmchen, T. Crowdsourcing of inventive activities, AI, and the NIH syndrome. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Items | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Manufacturing | 293 | 73.99% |

| Services | 50 | 12.63% | |

| Construction/infrastructure | 9 | 2.27% | |

| Agriculture/resources | 11 | 2.78% | |

| Other | 33 | 8.33% | |

| Company size (number of full-time employees) | 100–1500 | 107 | 27.02% |

| 1501–5000 | 188 | 47.47% | |

| 5001 or more | 101 | 25.51% | |

| Company age | Minimum five years to maximum 122 years | ||

| TMT size | Minimum eight to maximum 37 people | ||

| Listed market | China’s A-share market | Shanghai Stock Exchange | |

| Total sample size | 396 | ||

| Functional Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Firm-Level Average (per TMT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R&D | 2920 | 40.2 | 7.37 |

| Other | 1809 | 24.9 | 4.57 |

| Management | 732 | 10.1 | 1.85 |

| Finance | 644 | 8.9 | 1.63 |

| Marketing | 391 | 5.4 | 0.99 |

| Legal | 279 | 3.8 | 0.70 |

| Production/operation | 274 | 3.8 | 0.69 |

| HR | 223 | 3.1 | 0.56 |

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | VIF | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | 0.0211 | 0.0325 | −0.0838 | 0.1216 | - | 1 | |||||||

| TMT functional diversity | 0 | 1 | −4.4427 | 1.2899 | 1.084 | 0.088 | 1 | ||||||

| Innovativeness | 0 | 1 | −0.9431 | 9.3296 | 1.146 | −0.106 * | −0.178 ** | 1 | |||||

| Government R&D Subsidies | 0 | 1 | −4.2281 | 2.4175 | 1.309 | 0.080 | −0.142 ** | 0.212 ** | 1 | ||||

| Firm size | 7.9594 | 0.9838 | 4.9628 | 11.2558 | 1.294 | 0.273 ** | 0.056 | −0.082 | 0.370 ** | 1 | |||

| Firm age | 3.1153 | 0.2461 | 2.1972 | 3.7135 | 1.083 | −0.082 | 0.136 ** | −0.168 ** | 0.023 | 0.099 * | 1 | ||

| Fixed-asset ratio | 0.1995 | 0.1312 | 0.0011 | 0.7021 | 1.064 | −0.016 | 0.041 | −0.162 ** | −0.169 ** | 0.059 | −0.014 | 1 | |

| TMT size | 18.36 | 4.598 | 8 | 37 | 1.149 | −0.017 | 0.167 ** | −0.129 * | 0.074 | 0.272 ** | 0.215 ** | −0.001 | 1 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 396 | β | t | Β | t | β | t | β | t |

| Dependent Variable | ROA | |||||||

| Firm size | 0.306 *** | 6.125 | 0.302 *** | 6.077 | 0.308 *** | 6.211 | 0.298 *** | 5.524 |

| Firm age | −0.107 * | −2.158 | −0.121 * | −2.440 | −0.127 * | −2.563 | −0.125 * | −2.542 |

| Fixed-asset ratio | −0.040 | −0.835 | −0.057 | −1.176 | −0.066 | −1.362 | −0.054 | −1.109 |

| TMT size | −0.094 | −1.836 | −0.101 * | −1.983 | −0.097 | −1.897 | −0.090 | −1.774 |

| TMT functional diversity | 0.102 * | 2.087 | 0.087 | 1.767 | 0.077 | 1.559 | 0.060 | 1.195 |

| Innovativeness | −0.108 * | −2.166 | −0.100 * | −2.013 | −0.099 | −1.814 | ||

| TMT functional diversity * innovativeness | 0.099 * | 2.039 | 0.058 | 1.139 | ||||

| Government R&D subsidies | 0.063 | 1.094 | ||||||

| TMT functional diversity * government R&D subsidies | −0.059 | −1.132 | ||||||

| TMT functional diversity * government R&D subsidies | 0.073 | 1.241 | ||||||

| TMT functional diversity * innovativeness * government R&D subsidies | 0.209 ** | 3.491 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.104 | 0.114 | 0.124 | 0.151 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.092 | 0.101 | 0.108 | 0.127 | ||||

| Changes in R2 | 0.104 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.028 | ||||

| Sig. F change | 9.010 *** (p < 0.001) | 4.693 * (p = 0.031) | 4.157 * (p = 0.042) | 3.119 * (p = 0.015) | ||||

| F value | 9.010 *** | 8.362 *** | 7.819 *** | 6.219 *** | ||||

| Effect | S.E | t | p | LCCI | UCCI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovativeness | −1 SD | −0.0010 | 0.0025 | −0.4167 | 0.6772 | −0.0059 | 0.0038 |

| Mean | 0.0025 | 0.0016 | 1.5593 | 0.1197 | −0.0007 | 0.0056 | |

| +1 SD | 0.0062 | 0.0023 | 2.6998 | 0.0072 | 0.0017 | 0.0108 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, Y.J.; Wai, T.M.N.; Yoo, J.W. TMT Diversity and the Financial Performance of Listed Chinese Companies: Three-Way Interaction Analysis of Innovativeness and Government R&D Subsidies. Systems 2025, 13, 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100842

Chang YJ, Wai TMN, Yoo JW. TMT Diversity and the Financial Performance of Listed Chinese Companies: Three-Way Interaction Analysis of Innovativeness and Government R&D Subsidies. Systems. 2025; 13(10):842. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100842

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Yu Jin, Tin Myat Noe Wai, and Jae Wook Yoo. 2025. "TMT Diversity and the Financial Performance of Listed Chinese Companies: Three-Way Interaction Analysis of Innovativeness and Government R&D Subsidies" Systems 13, no. 10: 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100842

APA StyleChang, Y. J., Wai, T. M. N., & Yoo, J. W. (2025). TMT Diversity and the Financial Performance of Listed Chinese Companies: Three-Way Interaction Analysis of Innovativeness and Government R&D Subsidies. Systems, 13(10), 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13100842