Vegetation- and Environmental Changes on Non-Reclaimed Spoil Heaps in Southern Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

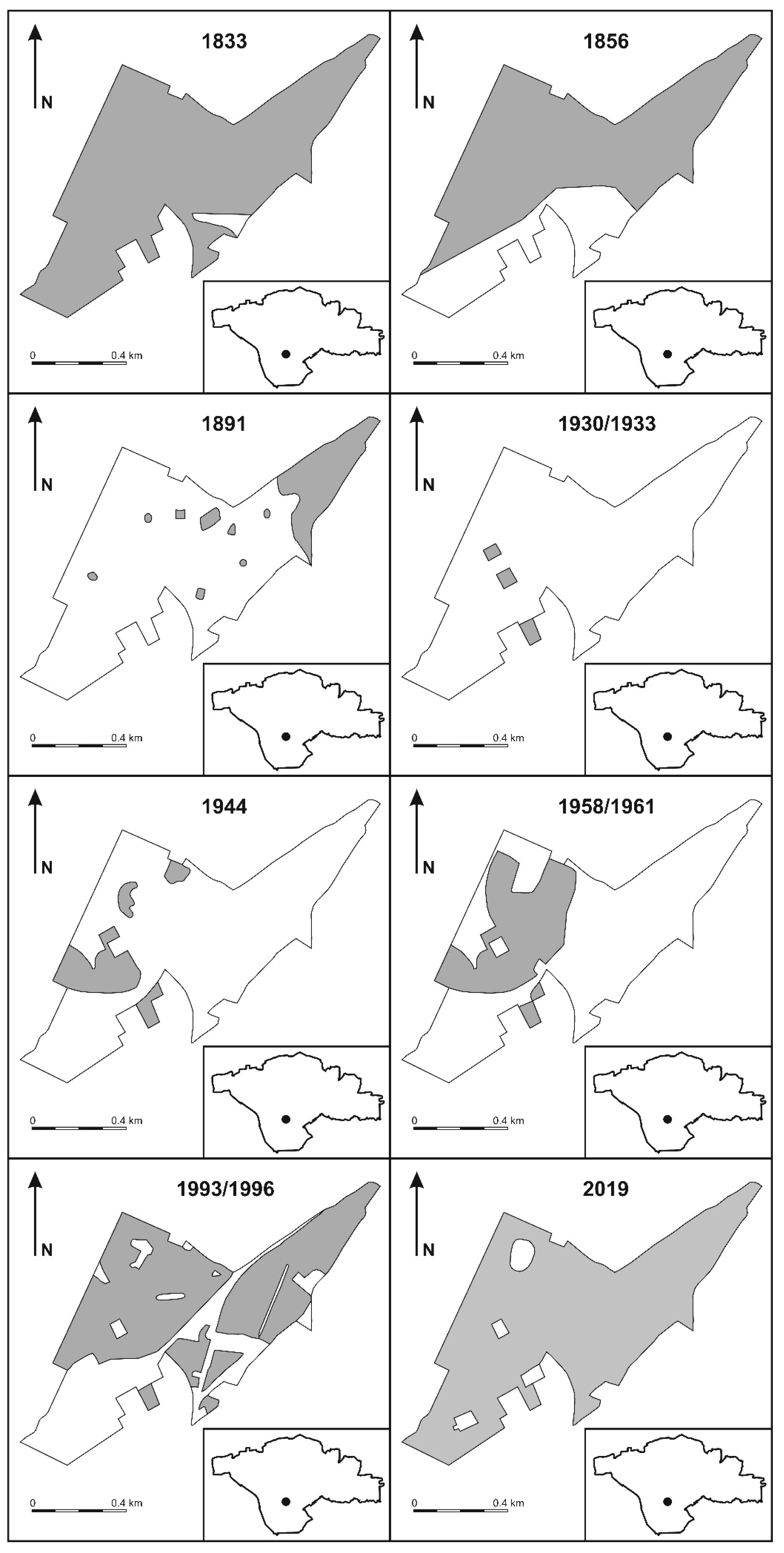

2.2. Analysis of Historical Cartographic Materials

2.3. Vegetation Investigation

2.4. Soil Investigations

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Vegetation Changes

3.1.1. Changes of Forested Area, 1833–2019

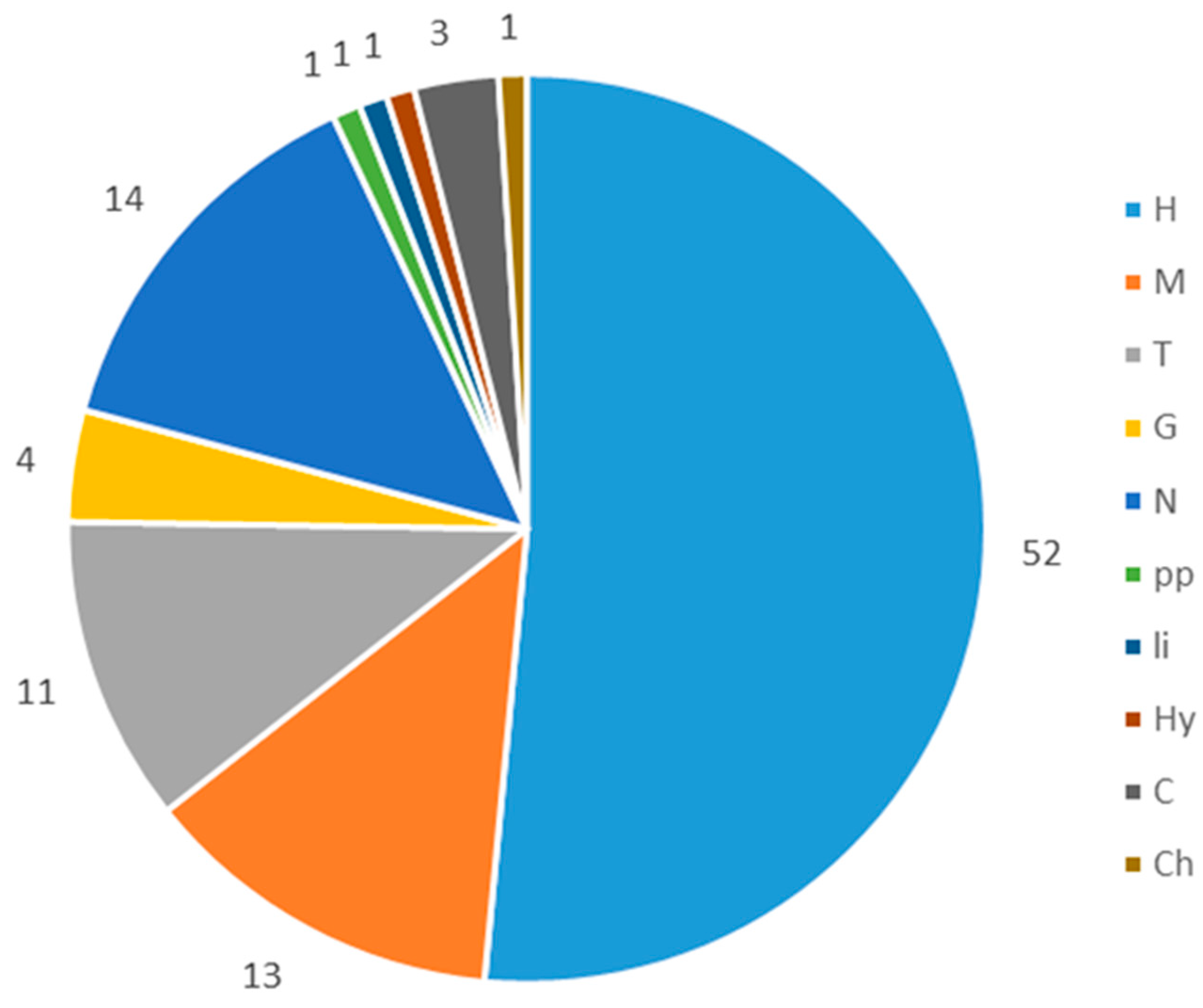

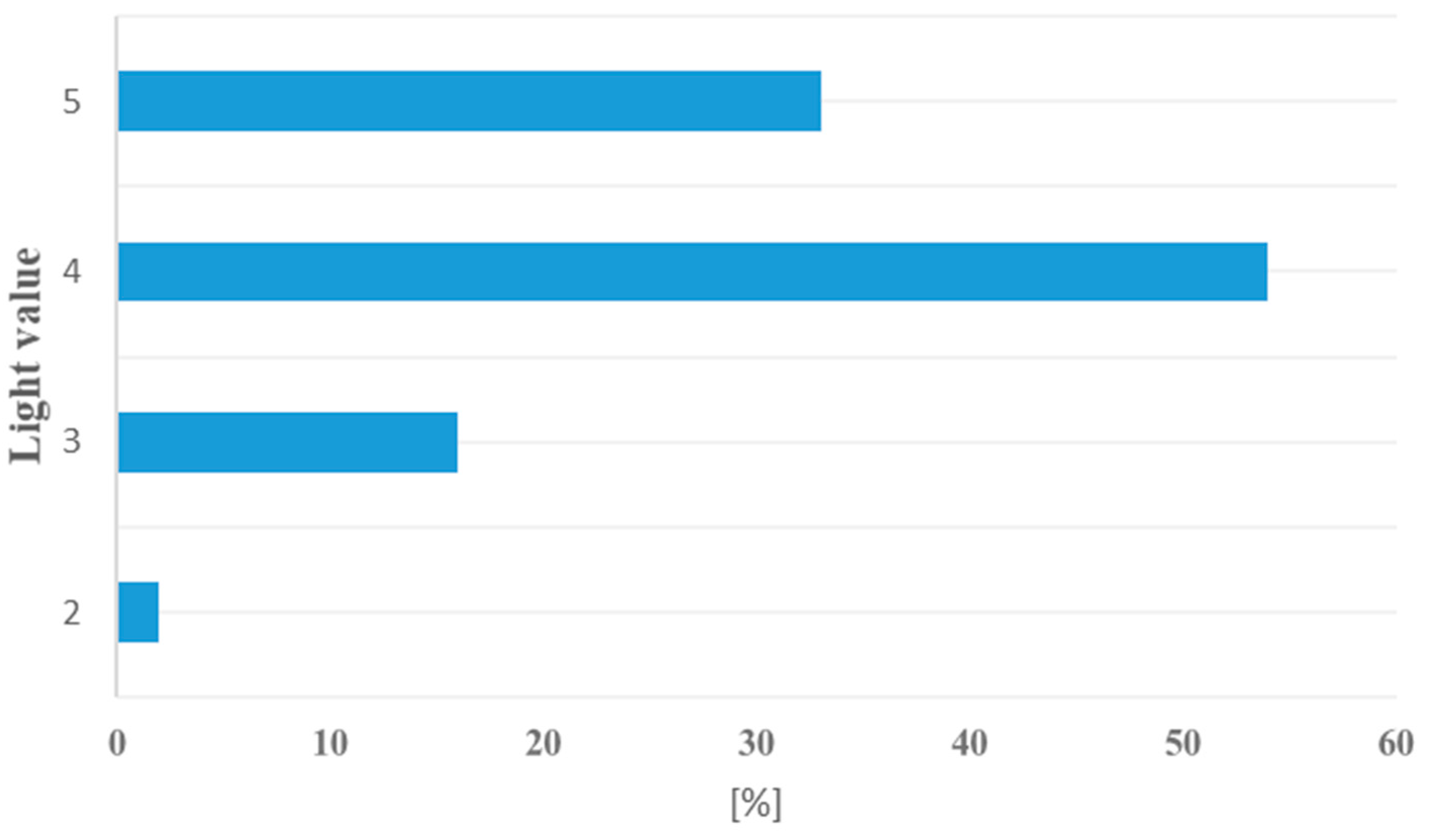

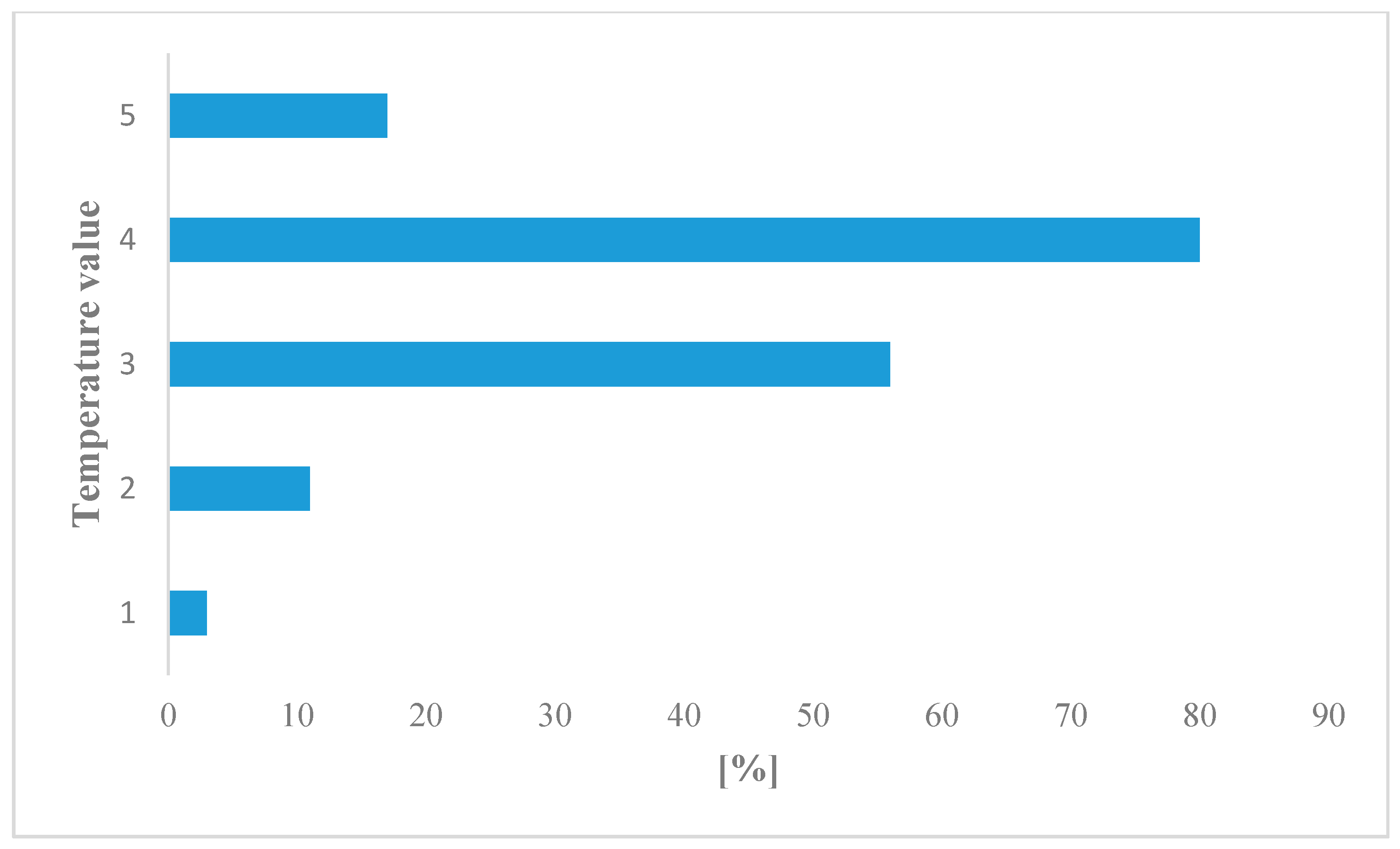

3.1.2. Spontaneous Succession

3.1.3. Secondary Succession

3.2. Flora Diversity

3.3. Chemical Properties of Soils in Sites under Different Vegetation Community

3.4. Correlation Coefficient in Sites

3.5. The Contents of Selected Macro Elements and Heavy Metals

- Site 2—Thickets of R. pseudoacacia: Fe > Al > Mg > S > K > P

- Site 6—Ulmus-Quercus stands: Fe > Al > Mg > K > S > P

- Site 9—Artificial birch stand: Fe > Al > Mg > K > S > P

- Site 10—Artificial pine stand: Fe > Al > Mg > S > K > P

- Site 2—Thickets of R. pseudoacacia L.: Zn > Mn > Pb > Cu > Sr > Ni > Cr > Co > Cd

- Site 6—Ulmus-Quercus stands: Zn > Mn > Pb > Cu > Ni > Cr > Sr > Co > Cd

- Site 9—Artificial birch stand: Zn > Pb > Mn > Cu > Sr > Cr > Ni > Cd > Co

- Site 10—Artificial pine stand: Zn > Pb > Mn > Cu > Sr > Ni > Cr > Cd > Co

4. Discussion

4.1. Vegetation Change in Base of Cartographic Analyses

4.2. Spontaneous and Secondary Succession

4.3. Differentiation of Soil Properties

4.4. Heavy Metal Concentration

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dulias, R. Landscape planning in areas of sand extraction in the Silesian Upland, Poland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 95, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaros, J. History of Coal Mining in Upper Silesian Coal Basin; Ossolineum: Wrocław, Poland, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Krzysztofik, R.; Runge, J.; Kantor-Pietraga, I. Paths of environmental and economic reclamation: The case of post-mining brownfields. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2012, 21, 219–223. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, R.T.T. Urban Ecology: Science of Cities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Frelich, L.E. Terrestrial Ecosystem Impacts of Sulfide Mining: Scope of Issues for the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, Minnesota, USA. Forests 2019, 10, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K.; Řehounková, K.; Lencová, K.; Jírová, A.; Konvalinková, P.; Mudrák, O.; Študent, V.; Vanecek, Z.; Tichy, L.; Petrik, P.; et al. Vegetation succession in restoration of disturbed sites in Central Europe: The direction of succession and species richness across 19 seres. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2014, 17, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumacher, I.; Pabjanek, P. Temporal Changes in Ecosystem Services in European Cities in the Continental Biogeographical Region in the Period from 1990–2012. Sustainability 2017, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayfield, B.; Anand, M.; Laurence, S. Assessing simple versus complex restoration strategies for industrially disturbed forests. Restor. Ecol. 2005, 13, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, C.; Skousen, J.; Pena-Yewtukhiw, E. Bulk density of rocky soils in forestry reclamation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2012, 76, 1810–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anawar, H.M.; Canha, N.; Santa-Regina, I.; Freitas, M.C. Adaptation, tolerance, and evolution of plant species in a pyrite mine, in response to contamination level and properties of mine tailings: Sustainable rehabilitation. J. Soils Sediments 2013, 13, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpitlaw, D.; Alsum, A.; Neale, D. Calculating ecological footprints for mining companies—An introduction to the methodology and assessment of the benefits. J. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2017, 117, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tarolli, P.; Sofia, G. Human topographic signatures and derived geomorphic processes across landscapes. Geomorphology 2016, 255, 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztofik, R.; Dulias, R.; Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Spórna, T.; Dragan, W. Paths of urban planning in a post-mining area. A case study of a former sandpit in southern Poland. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzaklewski, W. The method of directed succession in reclamation work. Postępy Techniki w Leśnictwie 1995, 56, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Grodzińska, K.; Korzeniak, U.; Szarek-Łukaszewska, G.; Godzik, B. Colonization of zinc mine spoils in Southern Poland—Preliminary studies on vegetation, seed rain, seed bank. Fragm. Florist. Geobot. 2001, 45, 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Rostański, A. Spontaneous Plant Cover on Colliery Spoil Heaps in Upper Silesia (Southern Poland); No. 2410; University of Silesia Publisher: Katowice, Poland, 2006. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, A.D. The use of natural processes in reclamation—Advantages and difficulties. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 51, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, A.; Pyšek, P.; Jarošyk, V.; Hajek, M. Diversity of native and alien plant species on rubbish dumps: Effects of dump age, environmental factors and toxicity. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 9, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegleb, G.; Felinks, B. Primary succession in post mining landscapes of lower Lusatia—Chance or necessity. Ecol. Eng. 2001, 17, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, G. Diversity of Vegetation on Coal-Mine Heaps of the Upper Silesia (Poland); Szafer, W., Ed.; Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences: Kraków, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Prach, K.; Lencová, K.; Řehounková, K.; Dvořáková, H.; Jírová, A.; Konvalinková, P.; Mudrák, O.; Novák, J.; Trnková, R. Spontaneous vegetation succession at different central European mining sites: A comparison across seres. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 7680–7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicia, P.; Bejger, R.; Błońska, A.; Zadrozny, P.; Gawlik, A. Characteristics of the habitat conditions of ash-alder carr (Fraxinio-Alnetum) in the Błędowskie Swamp. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2014, 12, 1227–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Urbancová, L.; Lacková, E.; Kvíčala, M.; Čecháková, L.; Čechák, J.; Stalmachová, B. Plant communities on brownfield sites in upper silesia (Czech Republic). Carpath. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2014, 9, 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Kodir, A.; Hartono, D.M.; Haeruman, H.; Mansur, I. Integrated post mining landscape for sustainable land use: A case study in South Sumatera, Indonesia. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2017, 27, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, H.R.; Moore, H.M.; Mcintosh, A.D. Land Reclamation Achieving Sustainable, Benefits. In 4th Internnational Conference, Proceedings of the International. Association of Land Reclamationists, Nottingham, UK, 7–11 September 1998; Balkema: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998; p. 560. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, K.G.; Willgoose, G.R. Post-mining landform evolution modelling: 2. Effects of vegetation and surface ripping. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2000, 25, 803–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Jaabir, M.; Sankaran, S. Geoenvironmental reclamation—Paddy cultivation in mercury polluted lands. In Geoenvironmental Reclamation; Paithankar, A.G., Jha, P.K., Agarwal, R.K., Eds.; Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2000; pp. 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Jochimsen, M.E. Vegetation development and species assemblages in a long-term reclamation project on mine spoil. Ecol. Eng. 2001, 17, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, G.R.; Loch, R.J.; Willgoose, G.R. The design of post-mining landscapes using geomorphic principles. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2003, 28, 1097–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzaklewski, W.; Pietrzykowski, M. Diagnoza siedlisk na terenach pogórniczych rekultywowanych dla leśnictwa, ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem metod fitosocjologiczno−glebowej. Sylwan 2007, 1, 51–57. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Ruiz, C.; Marrs, R.H. Some factors affecting successional change on uranium mine wastes: Insights for ecological restoration. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2007, 10, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ruiz, C.; Fernandez-Santos, B. Natural revegetation on top soiled uranium-mining spoils according to the exposure. Acta Oecol. 2005, 28, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Zhao, H.L. Changes in soil particles fraction and their effects on stability of soil-vegetation system in restoration processes of degraded sandy grassland. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2009, 18, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Błońska, A.; Kompała-Bąba, A.; Sierka, E.; Bierza, W.; Magurno, F.; Besenyei, L.; Ryś, K.; Woźniak, G. Diversity of vegetation dominated by selected grass species on coal-mine spoil heaps in terms of reclamation of post-industrial areas. J. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 20, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabała, J.; Idziak, A.F.; Szymala, A. Physicochemical and geophysical investigation of soils from former coal mining terrains in southern Poland. In Proceedings of the 15th Mining Planing and Equipment Section, Torino, Italy, 20–22 September 2006; Cardu, M., Ed.; pp. 543–548. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmonov, O.; Czylok, A.; Orczewska, A.; Majgier, L.; Parusel, T. Chemical composition of the leaves of Reynoutria japonica Houtt. and soil features in polluted areas. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2014, 9, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompała-Bąba, A.; Bierza, W.; Błońska, A.; Sierka, E.; Magurno, F.; Chmura, D.; Besenyei, L.; Radosz, Ł.; Woźniak, G. Vegetation diversity on coal mine spoil heaps—How important is the texture of the soil substrate? Biologia 2019, 74, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmonov, O.; Oleś, W. Vegetation succession over an area of a medieval ecological disaster. The case of the Błędów Desert, Poland. Erdkunde 2010, 64, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmonov, O.; Snytko, V.A.; Szczypek, T.; Parusel, T. Vegetation development on post-industrial territories of the Silesian Upland (Southern Poland). Geogr. Nat. Res. 2013, 34, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieswyk, C.B.; Johnston, C.A.; Zedler, J.B. Identifying and characterizing dominant plants as an indicator of community condition. J. Great Lakes Res. 2007, 33, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.Q.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Bao, B.; Sun, J.X. Variations of soil particle size distribution with land-use types and influences on soil organic carbon and nitrogen. J. Plant Ecol. 2008, 32, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Liu, S.R.; Cai, D.X.; Lu, L.H.; He, R.M.; Gao, Y.X.; Di, W.Z. Soil physical and chemical characteristics under different vegetation restoration patterns in China south subtropical area. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 21, 2479–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alday, J.G.; Marrs, R.H.; Martínez-Ruiz, C. Vegetation succession on reclaimed coal wastes in Spain: The influence of soil and environmental factors. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2011, 14, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Lavorel, S.; de Bello, F.; Quétier, F.; Grigulis, K.; Robson, T.M. Incorporating plant functional diversity effects in ecosystem service assessments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20684–20689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokany, K.; Ash, J.; Roxburgh, S. Functional identity is more important than diversity in influencing ecosystem processes in a temperate native grassland. J. Ecol. 2008, 96, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domański, B. Post-industrial area regeneration—Specificity of challenges and instruments. In Spatial Aspects of Revitalization of Downtowns, Housing Estates, Post-Industrial, Post-Military and Old-Railway Areas. Revitalization of Polish Cities; Jarczewski, W., Ed.; Institute of Urban and Regional Development: Kraków, Poland, 2009; pp. 125–138. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Fagiewicz, K. Spatial Processes of Landscape Transformation in Mining Areas (Case Study of Opencast Lignite. Mines in Morzysław, Niesłusz, Gosławice). Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2014, 23, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Drozdek, M.E.; Greinert, A.; Kostecki, J.; Tokarska-Osyczka, A.; Wasylewicz, R. Thematic parks in urban post-industrial areas. Acta Sci. Pol. Archit. 2017, 16, 65–77, (In Polish with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, J. Former mining areas of the Wałbrzych Basin 20 years after mine closures. Przegląd Geogr. 2018, 90, 267–290. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ground and Buildings Map of Niwki Bobrku and Naydowki 1: 12000, M. Kossecki, Archiwum Górnicze in Dąbrowa Górnicza, No. 527; National Archive in Katowice: Katowice, Poland, 1833. (In Polish)

- Hempel, J. Karta Geognostyczna Zagłębia Węglowego w Królestwie Polskiem, Ułożona z Rozkazu Dyrektora GÓRNICTWA JENERAŁA Majora Szenszyna Sekcja II (4). Scale 1:20000; Litografia M. Fajans: Warszawa, Poland, 1856. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Łempicki, M.; Gatowski, A. Płastowaja Karta Polskowo Kamiennougolnowo Basseina. Sheets: Mysłowice-Niwka P. II, p. 4 and Bobrek, P. II, p. 5, Scale 1: 10000; Kartograficzeskij Zawod: Sankt Petersburg, Russia, 1891. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Map of the Niwka Commune, Scale 1:10000; Municipal Office in Niwka: Sosnowiec, Poland, 1930. (In Polish)

- Topographic Map of Poland. Sheet Dąbrowa Górnicza, 1:25000; PAS-47-SŁUP 28-I; Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny: Warszawa, Poland, 1933. (In Polish)

- Aerial Photo (Military): Sosnowiec-South (digital version)—No. 2627. 1944; (unpublished).

- Sosnowiec. City Plan. 1:10000; Municipal Office in Sosnowiec: Sosnowiec, Poland, 1958. (In Polish)

- Topographic Map of Sosnowiec 1:25 000; Sztab Generalny Wojska Polskiego: Warszawa, Poland, 1961. (In Polish)

- Topographic Map of Poland. Sosnowiec, 1:10 000, M-34-63-A-b-3; Główny Geodeta Kraju: Warszawa, Poland, 1996. (In Polish)

- Paniecki, T. Problems with calibration of the detailed map of Poland in 1:25,000 published by the Military Geographical Institute (WIG) in Warsaw. Polski Przegląd Kartogr. 2014, 46, 162–172. [Google Scholar]

- Sobala, M. Application of Austrian cadastral maps in research on land use in the middle of 19th century. Polski Przegląd Kartogr. 2012, 44, 324–333. [Google Scholar]

- Różkowski, J.; Rahmonov, O.; Szymczyk, A. Environmental Transformations in the Area of the Kuźnica Warężyńska Sand Mine, Southern Poland. Land 2020, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflansensoziologie; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1964; p. 631. [Google Scholar]

- Studium Uwarunkowań i Kierunków Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Miasta Sosnowca; Municipal Office: Sosnowiec, Poland, 2016. Available online: http://bip.um.sosnowiec.pl/Article/id,6366.html (accessed on 13 July 2020). (In Polish)

- Rutkowski, L. Key for Vascular Plants Identification; Polish Scientific Press: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycki, K.; Trzcińska-Tacik, H.; Różański, W.; Szeląg, Z.; Wołek, J.; Korzeniak, U. Ecological Indicator Values of Vascular Plants of Poland; Szafer, W., Ed.; Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences: Kraków, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Matuszkiewicz, J.M. Potential Vegetation of Poland; Polish Academy of Science: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mirek, Z.; Piękoś-Mirkowa, H.; Zając, A.; Zając, M. Flowering Plants and Pteridophytes of Poland. A checklist. Biodiversity of Poland; Szafer, W., Ed.; Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences: Kraków, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhart, H. Phosphatkartierung und bodenkundliche Geländeuntersuchgen zur Eingrenzung historischer Siedlungs—Ung Wirtschaftsflächen der Geestinel Flögeln, Kreis Cuxhaven. Probl. Küstenforschung Südlichen Nordseegebiet 1982, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek, R.; Dziadowiec, H.; Pokojska, U.; Prusinkiewicz, Z. Badania Ekologiczno-Gleboznawcze; Z PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2004; p. 344. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt, W. Soils in urban and industrial environments. Z. Pflanzenernähr. Bodenk. 1994, 157, 214–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleś, W.; Rahmonov, O.; Rzętała, M.; Pytel, S.; Malik, I. The ways of industrial wastelands management in the Upper Silesian Region. Ekologia Bratisl. 2004, 23 (Suppl. 1), 244–251. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.Y.; Han, Y.Z.; Zhang, C.L.; Pei, Z.Y. Reclaimed soil properties and weathered gangue change characteristics under various vegetation types on gangue pile. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2011, 31, 6429–6441. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, B.T. Physical fractionation of soil and structural and functional complexity in organic matter turnover. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2001, 52, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemkemeyer, M.; Dohrmann, A.B.; Christensen, B.T.; Tebbe, C.C. Bacterial preferences for specific soil particle size fractions revealed by community analyses. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworek-Jakubska, J.; Filipiak, M.; Michalski, A.; Napierała-Filipiak, A. Spatio-Temporal Changes of Urban Forests and Planning Evolution in a Highly Dynamical Urban Area: The Case Study of Wrocław, Poland. Forests 2020, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekarska-Stachowiak, A.; Szary, M.; Ziemer, B.; Besenyei, L.; Woźniak, G. An application of the plant functional group concept to restoration practice on coal mine spoil heaps. Ecol. Res. 2014, 29843–29853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebele, F.; Lehmann, C. Biological Flora of Central Europe: Calamagrostis epigejos (L.) Roth. Flora 2001, 196, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmonov, O. The chemical composition of plant litter of black locust (Robinia pseudacacia L.) and its ecological role in sandy ecosystems. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2009, 29, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozińska, A.; Greinert, M.; Greinert, A. The concept of reclamation and development of part of the former “Niwka” Coal Mine area in Sosnowiec. Przegląd Bud. 2013, 3, 82–85. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Prach, K. Spontaneous succession in central-European man-made habitats: What information can be used in restoration practice? Appl. Veg. Sci. 2003, 6, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRB (World Reference Base for Soil Resources); Foood and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015.

- Alday, J.G.; Marrs, R.H.; Martínez-Ruiz, C. Soil and vegetation development during early succession on restored coal wastes: A 6 year permanent plot study. Plant Soil 2012, 353, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Z.; Wang, S.P.; Han, X.G.; Chen, Q.S.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Zhang, S.M.; Yang, J. Soil nitrogen regime and the relationship between aboveground green phytobiomass and soil nitrogen fractions at different stocking rates in the Xilin river basin, Inner Mongolia. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2004, 28, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Biasioli, M.; Barberis, R.; Ajmone-Marsan, F. The influence of a large city on some soil properties and metals content. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 356, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Miguel, E.; Jimenez de Grado, M.; Llamas, J.F.; Martın-Dorado, A.; Mazadiego, L. The overlooked contribution of compost application to the trace element load in the urban soil of Madrid (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 1998, 215, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmonov, O.; Banaszek, J.; Pukowiec-Kurda, K. Relationships between Heavy Metal Concentrations in Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria Japonica Houtt.) Tissues and Soil in Urban Parks in Southern Poland. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperato, M.; Adamo, P.; Naimo, D.; Arienzo, M.; Stanzione, D.; Violante, P. Spatial distribution of heavy metals in urban soils of Naples city (Italy). Environ. Pollut. 2003, 124, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Succession Stage | Type of Vegetation | Habitat Features and Others Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous succession | Psammophilic turf—mostly Corynephorus canescens, Heracium pilosella, Hernaria glabra, Oenothera biennis, Trifolium arvense, Berteroa incana | Sand pit with a patch of loose sands, open area. |

| Community of Juncus effusus, Carduus acanthoides, Phragmites australis, Juncus articulatus, Deschampsia caespitosa, on its periphery, Sonchus arvensis, Fragaria vesca, Medicago sativa, M. lupulina Potentilla anserina, Dactylis glomerata, Vicia cracca, Agrostis canina occur. Young specimens of trees and shrubs of Alnus glutinosa, Populus tremula, Salix rosmarinifolia, Salix caprea | Impervious soils (heavy clays), periodic rainwater collects, wetland habitat. | |

| Calamagrostietum epigeji forms mostly monospecific, compact community, Hypericum perforatum and Symphyotrichum novi-belgii occur rarely | Dry, sunny terrain on post-mining debris characterized by various fractions and compaction degree (from loose to cemented). | |

| Rudbeckio-Solidaginetium: Rudbeckia laciniata, Solidago canadensis | ||

| Scrubs of Robinia pesudacacia and Betula pendula (3–4 m tall), groundcover is covered by Calamagrostietum epigeji, sometimes individually S. virgaurea occurs | ||

| Arctio-Artemisietum vulgaris: Arctium tomentosum, Artemisia vulgaris, Solidago virgaurea, Arctium tomentosum, Verbascum nigrum, Epilobium angustifolium, Urtica dioica, and Chelidonium majus | Former orchard, open area with construction debris, organic and mineral hills. | |

| Initial birch forest: Tree layer: Betula pendula, Quercus robur, Quercus rubra, Robinia pseudoacacia, Populus tremula, Pinus nigra, Ulmus laevis, Acer platanoides, Acer pseudoplatanus, Alnus glutionosa Shrub layer: Euonymus europaeus, Coryllus avellana, Prunus spinosa, Prunus cerasus Padus serotina, Rhamnus cathartica, Crataegus monogyna, Viburnum opulus. Herbaceous plants: Viola reichenbachiana, Dryopteris filix-mas, Geum urbanum, Vinca minor, Rubus idaeus, Chelidonium majus, Reynoutria japonica | Anthropogenic field form, where natural succession occur (it was not reclaimed). Birch is co-dominant with other species (Figure 2). | |

| Initial pine forest: Tree layer: Pinus sylvestri, Betula pendula, Quercus robur, Quercus rubra, Robinia pseudoacacia, Acer pseudoplatanus. Herbaceous plants: Maianthemum bifolium, Geum urbanum, Equisetum sylvaticum | Flat surface, covered by poorly decaying pine fall. | |

| Initial elm and oak forest: Tree layer: Ulmus laevis, Quercus robur, Carpinus betulus, Acer platanoides, Acer pseudoplatanus, Betula obscura, Aesculus hipocastanum Shrub layer: Corylus avellana, Prunus serotina, Crataegus monogyna, Cornus sanguinea, Sambucius nigra. Herbaceous plants: Viola reichenbachiana, Dryopteris filix-mas, Geum urbanum, Vinca minor, Rubus idaeus, Chelidonium majus | Slope of the military bunker with 16 m height. | |

| Alder riparian forest (Fraxino-Alnetum): Alnus glutinosa, Betula pendula, Salix alba, Salix fragilis, Salix purpurea, Salix caprea, Padus avium. Groundcover: Lysimachia vulgaris, Solanum dulcamarum, Potentilla anserina, Lycopus europaeus, Eupatorium cannabinum, Deschampsia caespitosa | Terrain depressions of various sizes, impermeable substrate. | |

| Black locust forest: Tree layer: Robinia pseudoacacia, Quercus robur, Quercus rubra, Tilia cordata. Shrub layer: Corylus avellana and growths of Carpinus betulus mostly, individual Prunus serotina. Herbaceous plants: Chelidonium majus, Urtica dioica, Geum urbanum, Convallaria majalis, Viola minor | It covered high, raised terrain forms of a loose nature. | |

| Artificial planting | Artificial initial birch forest: Tree layer: Betula pendula, Tilia americana, Quercus rubra, Acer saccharinum, Populus x canadensis ‘Serotina’, Pinus nigra, Robinia pseudoacacia, Acer pseudoplatanus Shrub layer: Sorbus aucuparia, Malus sylvestris, Symphoricarpos albus, Spiraea salicifolia Herbaceous plants: Taraxacum officinale, Trifolium repens, Trifolium pratense, Polygonum aviculare, Melandrium album, Lolium perenne, Achillea millefolium, Solidago virgaurea, Geranium phaeum, Ranunculus acris, Aegopodium podagraria, Arctium lappa, Prunella vulgaris, Plantago lanceolata, Plantago major, Rumex acetosa, Artemisia vulgaris, etc. Small patches of Lolio-Plantaginetum formed along the paths in the park | Arranged city park with leveled surface and unfavorable water-air relations in the soil (caused by trampling). |

| Artificial initial pine forest: Tree layer: Pine sylvestris mostly, Quercus robur individually as an admixture, Acer psedoplatanus Shrub layer: Sorbus aucuparia, Padus serotina and tree growths Herbaceous plants:—individual Viola reichenbachiana, Maianthemum bifolium, Rubus caesius, Rubus idaeus | Flat surface covered with poorly distributed pine fall. The population is evenly distributed with specimens characterized by the same age, no undergrowth, poor ground cover. | |

| Alley with Robinia pseudoacacia: Acer platanoides, Rosa rugosa, Berberis thunbergii, Ligustrum vulgare |

| Number of Sites | Texture (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Skeleton | Fine Earth | ||||||||

| [mm] | |||||||||

| >10.0 | 10.0–5.0 | 5.0–2.0 | 2.0–1.0 | 1.0–0.5 | 0.5–0.25 | 0.25–0.1 | 0.1–0.05 | <0.05 | |

| 1 * | 7.5 | 15.4 | 16.9 | 16.2 | 7.8 | 11.1 | 12.8 | 7.4 | 4.9 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 2.9 | 15.5 | 33.2 | 30.5 | 8.9 | 7.8 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 15.0 | 40.9 | 33.8 | 3.4 | 1.9 |

| 4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 11.9 | 31.2 | 32.4 | 10.5 | 11.2 |

| 5 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 3.2 | 9.6 | 25.3 | 35.8 | 14.1 | 9.4 |

| 6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 4.7 | 19.7 | 31.3 | 31.9 | 6.2 | 4.0 |

| 7 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 11.3 | 24.9 | 37.9 | 10.5 | 10.4 |

| 8 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 19.3 | 33.8 | 28.9 | 8.3 | 5.9 |

| 9 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 17.4 | 41.4 | 25.9 | 3.9 | 3.5 |

| 10 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 19.1 | 33.9 | 34.3 | 5.8 | 1.9 |

| 11 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 26.0 | 29.1 | 18.8 | 18.2 |

| 12 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 9.8 | 20.5 | 34.9 | 16.9 | 13.2 |

| Number of Sites/Vegetation Community | Hh | pH | Loss Ignition | Corg | Nt | C/N | Mg Available | P Available | Pt | K Available | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmol (+)kg−1 | H2O | KCl | [%] | [mg·kg−1] | ||||||||

| 1. | Calamagrostis epegijos | 7.29 (±0.02) | 5.7 (±0.19) | 5.0 (±0.14) | 29.43 (±0.5) a.b | 16.84 (±0.2) | 0.35 (±0.01) | 48.67 (±1.53) b | 205.43 (±0.5) a | 4.75 (±0.12) a.b | 162.5 (±2.59) | 188.1 (±2.42) |

| 2. | Thickets of R. pseudoacacia | 7.55 (±0.04) | 5.8 (±0.16) | 5.3 (±0.10) | 18.64 (±0.25) | 10.48 (±0.21) | 0.35 (±0.004) | 30 (±1.0) | 181.87 (±1.64) | 26.37 (±0.68) | 354.07 (±2.53) | 227.69 (±3.97) a |

| 3. | Alder community | 5.22 (±0.02) | 5.4 (±0.15) | 4.9 (±0.15) | 7.68 (±0.20) | 4.51 (±0.39) | 0.2 (±0.01) | 23 (±2.00) | 105.8 (±2.88) | 7.66 (±0.39) | 150.63 (±1.66) | 45.46 (±0.91) c |

| 4. | Populus-Betula stands | 10.52 (±0.04) | 5.3 (±0.1) | 4.7 (±0.06) | 18.84 (±0.25) | 13.67 (±0.35) | 0.6 (±0.01) b.c | 22.67 (±0.58) | 147.7 (±1.67) | 15.26 (±0.72) | 366.03 (±4.54) | 163.9 (±2.27) |

| 5. | Juncus effusus community | 6.52 (±0.01) | 5.7 (±0.05) | 5.3 (±0.1) | 17.07 (±0.15) | 11.54 (±0.14) | 0.34 (±0.01) | 33.33 (±0.58) | 221 (±1.32) b.c | 26.52 (±0.78) | 235.27 (±5.11) | 193.48 (±2.23) |

| 6. | Ulmus-Quercus stands | 4.45 (±0.04) c | 5.7 (±0.16) | 5.1 (±0.11) | 6.22 (±0.2) a | 3.17 (±0.07) a | 0.14 (±0.004) c | 23 (±0) | 85.23 (±2.97) | 14.57 (±0.37) | 143.2 (±2.1) c | 133.51 (±0.58) |

| 7. | Birch (Betula) stand | 10.67 (±0.01) a | 5.5 (±0.1) | 5.0 (±0.12) | 21.74 (±0.25) | 9.37 (±0.16) | 0.46 (±0.005) a | 20.33 (±0.58) a.b | 145.27 (±1.66) | 62.74 (±2.43) b.c | 593.17 (±4.56) b.c | 128.8 (±1.75) |

| 8. | Robinia pseudoacacia stand | 9.31 (±0.02) | 4.6 (±0.11) b | 4.1 (±0.17) | 10.88 (±0.16) | 6.92 (±0.07) | 0.27 (±0.003) | 26 (±0) | 26.6 (±1.4) c | 33.26 (±2.74) a | 189.27 (±1.9) | 134.84 (±2.22) |

| 9. | Artificial birch stand | 4.07 (±0.02) a.b | 5.9 (±0.1) a.b | 5.3 (±0.1) | 6.33 (±0.15) b | 3.2 (±0.11) b | 0.09 (±0.003) a.b | 36.67 (±2.31) | 59.43 (±0.86) | 5.41 (±0.49) c | 197.27 (±2.23) | 62.87 (±1.7) |

| 10. | Artificial pine stand | 6.23 (±1.75) | 4.7 (±0.11) a | 4.2 (±0.18) | 6.51 (±0.1) | 3.74 (±0.11) | 0.16 (±0.01) | 23.33 (±1.15) | 23.33 (±1.15) | 5.9 (±0.36) a.b | 142.23 (±2.35) a.b | 35.87 (±2.59) a.b |

| 11. | Acer-Betula stands | 5.18 (±0.03) | 5.6 (±0.12) | 5.1 (±0.08) | 10.22 (±0.2) | 5.44 (±0.19) | 0.19 (±0.003) | 29.33 (±0.58) | 29.33 (±0.58) | 150.8 (±2.46) | 164.83 (±1.56) | 183.66 (±2.21) |

| 12. | Quercus-Pinus stand | 14.65 (±0.04) b.c | 5.2 (±0.15) | 4.8 (±0.1) | 26.52 (±0.4) | 17.73 (±0.21) a.b | 0.42 (±0.003) | 42.67 (±0.58) a | 42.67 (±0.58) a | 184.07 (±3.77) | 473.07 (±5.2) a | 346.19 (±2.92) b.c |

| p-value | 0.0004 * | 0.0012 * | 0.0008 * | 0.0003 * | 0.0003 * | 0.0003 * | 0.0004 * | 0.0003 * | 0.0003 * | 0.0003 * | 0.0003 * | |

| Soil Properties | Number of Sites | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hh [cmol (+) kg−1] | 7–9 | 0.032 | |

| 9–12 | 0.008 | ||

| 6–12 | 0.049 | ||

| H2O [pH] | 9–10 | 0.025 | |

| 8–9 | 0.039 | ||

| Loss ignition [%] | 1–6 | 0.014 | |

| 1–9 | 0.024 | ||

| Corg [%] | 6–12 | 0.014 | |

| 9–12 | 0.019 | ||

| Nt [%] | 7–9 | 0.032 | |

| 4–9 | 0.008 | ||

| 4–6 | 0.032 | ||

| C/N | 7–12 | 0.033 | |

| 1–7 | 0.008 | ||

| [mg·kg−1] | Mg available | 1–10 | 0.032 |

| 5–10 | 0.008 | ||

| 5–8 | 0.032 | ||

| P available | 1–8 | 0.032 | |

| 1–7 | 0.008 | ||

| 7–9 | 0.032 | ||

| Pt | 10–12 | 0.049 | |

| 7–10 | 0.013 | ||

| 6–7 | 0.021 | ||

| K available | 2–10 | 0.032 | |

| 10–12 | 0.008 | ||

| 3–12 | 0.032 | ||

| Soil Parameters/Site Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corg/Kavail. | 0.9996 (p = 0.019) | |||||||||

| Corg/Nt | 0.9995 (p = 0.021) | |||||||||

| Corg/Pavail. | 0.9972 (p = 0.048) | 0.9998 (p = 0.012) | ||||||||

| Corg/Pt | 0.9976 (p = 0.045) | 1.0000 (p = 0.002) | 0.9999 (p = 0.010) | |||||||

| Mgavail./Kavail. | 0.9991 (p = 0.026) | |||||||||

| Mgavail./Nt | 0.9996 (p = 0.019) | 0.9971 (p = 0.049) | 0.9983 (p = 0.037) | 1.0000 (p = 0.006) | ||||||

| Mgavail./Pavail. | 1.0000 (p = 0.005) | 0.9995 (p = 0.020) | 0.9999 (p = 0.010) | |||||||

| Nt/Kavail. | 0.9981 (p=0.040) | 0.9987 (p = 0.032) | ||||||||

| Pt/Kavail. | 0.9995 (p = 0.020) | 1.0000 (p = 0.002) | ||||||||

| Pt/Mgavail. | 0.9986 (p = 0.034) | 0.9999 (p = 0.010) | ||||||||

| Pt/Nt | 0.9999 (p = 0.009) | 0.9995 (p 0.019) | ||||||||

| Pt/Pavail. | 0.9997 (p = 0.015) |

| Number Sites/Vegetation Community | Cu | Pb | Zn | Ni | Co | Mn | Sr | Cd | Cr | P | Mg | K | Al | Fe | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mg·kg−1] | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Thickets of R. pseudoacacia | 45.88 | 266.01 | 798.9 | 21.0 | 7.8 | 509 | 34.4 | 5.96 | 15.3 | 480 | 1400 | 900 | 6000 | 19,000 | 13,000 |

| 6. Ulmus-Quercus stands | 23.75 | 170.83 | 526.1 | 22.7 | 11.7 | 250 | 16.0 | 4.57 | 16.3 | 390 | 1400 | 800 | 5900 | 14,000 | 400 |

| 9. Artificial birch stand | 36.79 | 403.66 | 1060.4 | 15.5 | 4.6 | 243 | 24.7 | 11.99 | 18.7 | 580 | 800 | 600 | 11,200 | 19,000 | 600 |

| 10. Artificial pine stand | 35.75 | 300.67 | 581.2 | 12.6 | 4.5 | 279 | 15.1 | 11.66 | 12.4 | 290 | 600 | 400 | 5000 | 13,300 | 500 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahmonov, O.; Krzysztofik, R.; Środek, D.; Smolarek-Lach, J. Vegetation- and Environmental Changes on Non-Reclaimed Spoil Heaps in Southern Poland. Biology 2020, 9, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9070164

Rahmonov O, Krzysztofik R, Środek D, Smolarek-Lach J. Vegetation- and Environmental Changes on Non-Reclaimed Spoil Heaps in Southern Poland. Biology. 2020; 9(7):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9070164

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahmonov, Oimahmad, Robert Krzysztofik, Dorota Środek, and Justyna Smolarek-Lach. 2020. "Vegetation- and Environmental Changes on Non-Reclaimed Spoil Heaps in Southern Poland" Biology 9, no. 7: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9070164

APA StyleRahmonov, O., Krzysztofik, R., Środek, D., & Smolarek-Lach, J. (2020). Vegetation- and Environmental Changes on Non-Reclaimed Spoil Heaps in Southern Poland. Biology, 9(7), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9070164