The Effect of Freeze-Thaw Conditions on Arctic Soil Bacterial Communities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Will Climate Change Stress Arctic Soil Communities, and What Are the Likely Ecological Impacts?

1.2. Freeze-Thaw: Survival of the Fittest, or an Assemblage of Defenses?

2. Experimental Section: The Effect of Simulated Freeze-Thaw Cycles on Latitudinally Distinct Soils

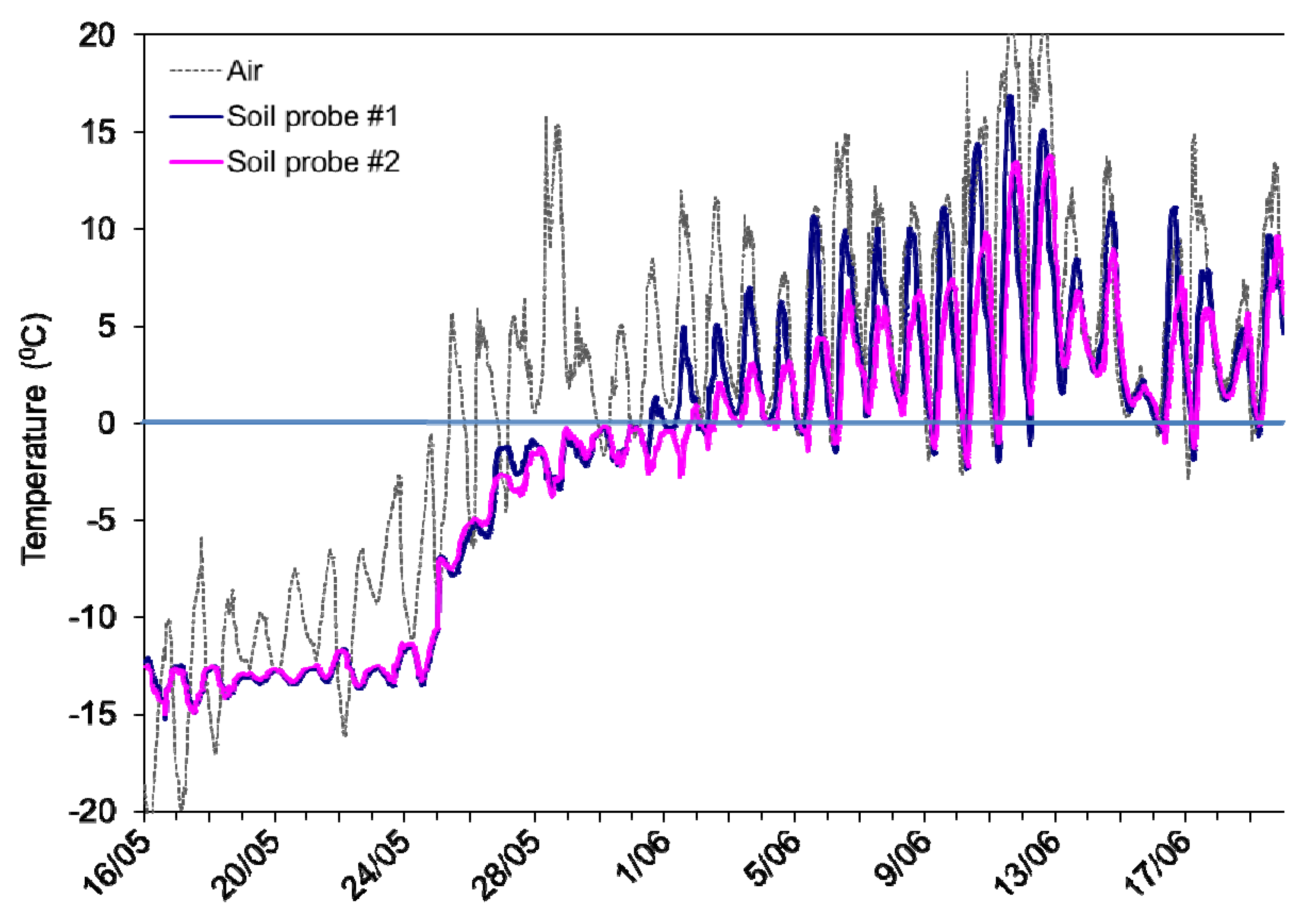

2.1. Soil Collection Sites, Freeze-Thaw Regime and Respiration Monitoring

| Site | pH | Org layer (cm) | Soil C (%) | Soil N (%) | Soil P (ppm) | AT (°C) | GST (°C) | AP (mm) | Snow depth (cm) | Days above 0 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL 1 | 4.3 | 2–5 | 20 | 0.7 | 21 | –9 | 3 | 150 | 29 | 127 |

| CB 2 | 6.6 | 5–6 | 24 | 1.4 | 7 | –14 | 6 | 140 | 31 | 79 |

| AF 3 | 5.6 | NA | 12 | 0.8 | 4 | –15 | 10 | 250 | NA | ~65 |

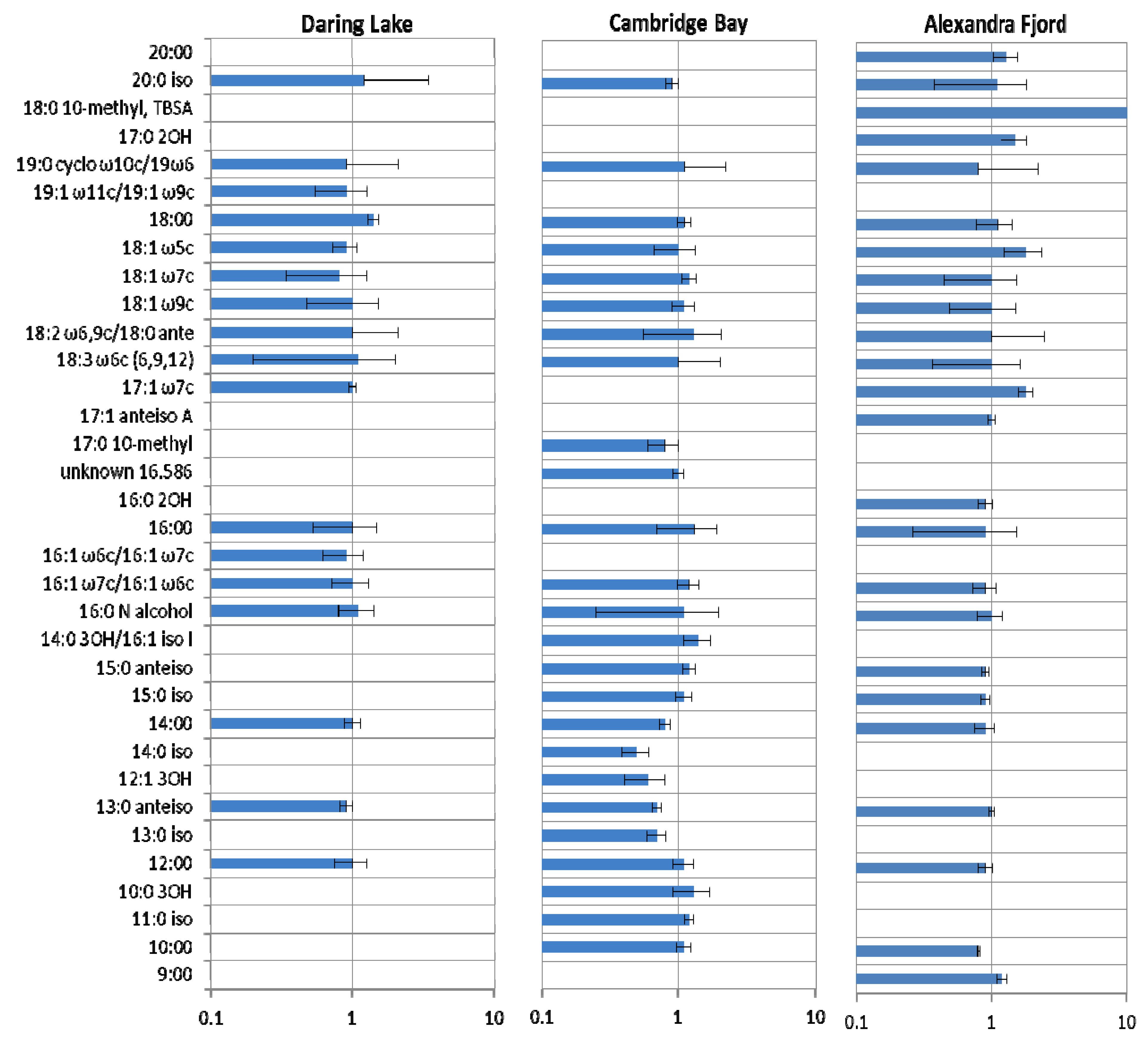

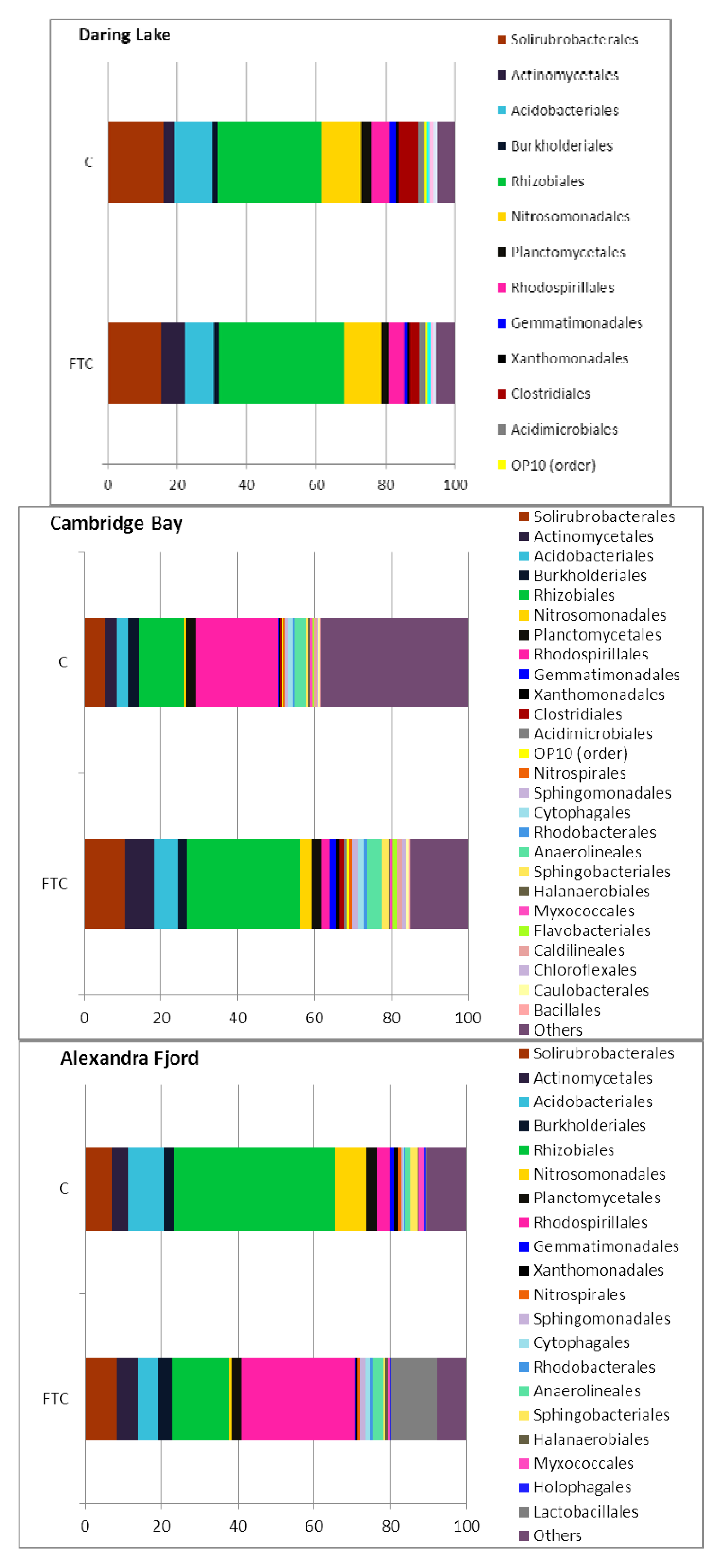

2.2. Soil Phospholipid Fatty Acid and DNA Analyses

2.3. Community Responses of Freeze-Thaw Stresses in Microcosms: Results

3. Discussion and Conclusions

3.1. Implications of the Microcosm Investigations

3.2. Implications for Predictions on the Effect of Climate Change

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- Olsson, P.Q.; Sturm, M.; Racine, C.H.; Romanovsky, V.; Liston, G.E. Five Stages of the Alaskan Arctic Cold Season with Ecosystem Implications. Arctic Antarct. Alp. Res. 2003, 35, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, P.D.; Grogan, P.; Templer, P.H.; Groffman, P.; Öquist, M.G.; Schimel, J.P. Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling in Snow-Covered Environments. Geogr. Compass. 2011, 5, 682–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkava, P.; Huhta, V. Effects of Hard Frost and Freeze-Thaw Cycles on Decomposer Communities and N Mineralisation in Boreal Forest Soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2003, 22, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, P.; Michelsen, A.; Ambus, P.; Jonasson, S. Freeze-Thaw Regime Effects on Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics in Sub-Arctic Heath Tundra Mesocosms. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, Y.; Toyota, K.; Okazaki, M. Effects of Successive Soil Freeze-Thaw Cycles on Soil Microbial Biomass and Organic Matter Decomposition Potential of Soils. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2004, 50, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Szele, Z.; Schilling, R.; Munch, J.C.; Schloter, M. Influence of Freeze-Thaw Stress on the Structure and Function of Microbial Communities and Denitrifying Populations in Soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 2148–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Schimel, J.; Balser, T.C.; Wallenstein, M. Microbial Stress-Response Physiology and its Implications for Ecosystem Function. Ecology 2007, 88, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, H.A.L. Soil Freeze-Thaw Cycle Experiments: Trends, Methodological Weaknesses and Suggested Improvements. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACIA: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; p. 1042.

- IPCC, Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.B.; Tignor, M.; Miller, H.L. (Eds.) Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007.

- Groffman, P.M.; Driscoll, C.T.; Fahey, T.J.; Hardy, J.P.; Fitzhugh, R.D.; Tierney, G.L. Colder Soils in a Warmer World: A Snow Manipulation Study in a Northern Hardwood Forest Ecosystem. Biogeochemistry 2001, 56, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattsov, V.M.; Källén, E.; Cattle, H.; Christensen, J.; Drange, H.; Hanssen-Bauer, I.; Jóhannesen, T.; Karol, I.; Räisänen, J.; Svensson, G.; et al. Future Climate Change: Modeling and Scenarios for the Arctic. In Arctic Climate Impact Assessment; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 99–150. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, P.D.; Williams, M.W.; Schmidt, S.K. Inorganic Nitrogen and Microbial Biomass Dynamics Before and During Spring Snowmelt. Biogeochemistry 1998, 43, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimel, J.P.; Clein, J.S. Microbial Response to Freeze-Thaw Cycles in Tundra and Taiga Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.S.; Jonasson, S.; Michelsen, A. Repeated Freeze-Thaw Cycles and Their Effects on Biological Processes in Two Arctic Ecosystem Types. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2002, 21, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.S.; Grogan, P.; Jonasson, S.; Michelsen, A. Respiration and Microbial Dynamics in Two Subarctic Ecosystems During Winter and Spring Thaw: Effects of Increased Snow Depth. Arctic Antarct. Alp. Res. 2007, 39, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, C.T.; Svendsen, S.H.; Schmidt, N.M.; Michelsen, A. High Arctic Heath Soil Respiration and Biogeochemical Dynamics During Summer and Autumn Freeze-in—Effects of Long-term Enhanced Water and Nutrient Supply. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 3224–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulides, D.A.; Allison, F.E. Effect of Drying and Freezing Soils on Carbon Dioxide Production, Available Mineral Nutrients, Aggregation, and Bacterial Population. Soil Sci. 1961, 91, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, D.A.; Monson, R.K. Plant-Microbe Competition for Soil Amino Acids in the Alpine Tundra: Effects of Freeze-Thaw and Dry-Rewet Events. Oecologia 1998, 113, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckeridge, K.M.; Cen, Y.-P.; Layzell, D.B.; Grogan, P. Soil Biogeochemistry During the Early Spring in Low Arctic Mesic Tundra and the Impacts of Deepened Snow and Enhanced Nitrogen Availability. Biogeochemistry 2010, 99, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Männistö, M.K.; Tiirola, M.; Haggblom, M.M. Effect of Freeze-Thaw Cycles on Bacterial Communities of Arctic Tundra Soil. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 58, 621–631. [Google Scholar]

- Skogland, T.; Lomeland, S.; Goksoyr, J. Respiratory Burst after Freezing and Thawing of Soil—Experiments with Soil Bacteria. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1988, 20, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, A.; Witter, E. Sources of C and N Contributing to the Flush in Mineralization upon Freeze-Thaw Cycles in Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, G.R.; Chapin, F.S. Response to Fertilization by Various Plant-Growth Forms in an Alaskan Tundra—Nutrient Accumulation and Growth. Ecology 1980, 61, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonasson, S.; Michelsen, A.; Schmidt, I.K. Coupling of Nutrient Cycling and Carbon Dynamics in the Arctic, Integration of Soil Microbial and Plant Processes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 1999, 11, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, G.R.; Billings, W.D.; Chapin, F.S., III; Giblin, A.E.; Nadelhoffer, K.J.; Oechel, W.C.; Rastetter, E.B. Global Change and the Carbon Balance of Arctic Ecosystems. BioScience 1992, 42, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.A.; Jefferies, R.L. Nitrogen uptake by Carex aquatilis during the winter-spring transition in a low Arctic wet meadow. J. Ecol. 2010, 98, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, P.; Jonasson, S. Controls on Annual Nitrogen Cycling in the Understorey of a Sub-Arctic Birch Forest. Ecology 2003, 84, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.S.; Michelsen, A.; Jonasson, S.; Beier, C.; Grogan, P. Nitrogen Uptake during Fall, Winter and Spring Differs among Plant Functional Groups in a Subarctic Heath Ecosystem. Ecosystems 2012, 15, 927–939. [Google Scholar]

- Bottner, P. Response of Microbial Biomass to Alternate Moist and Dry Conditions in a Soil Incubated with C-14-labeled and N-15-labelled Plant-Material. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1985, 17, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieft, T.L.; Soroker, E.; Firestone, M.K. Microbial Biomass Response to a Rapid Increase in Water Potential When Dry soil is Wetted. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clein, J.S.; Schimel, J.P. Reduction in Microbial Activity in Birch Litter due to Drying and Rewetting Events. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1994, 26, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Schimel, J.P. A Proposed Mechanism for the Pulse in Carbon Dioxide Production Commonly Observed Following the Rapid Rewetting of a Dry Soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2003, 67, 798–805. [Google Scholar]

- Franzluebbers, A.J.; Haney, R.L.; Honeycutt, C.W.; Schomberg, H.H.; Hons, F.M. Flush of Carbon Dioxide Following Rewetting of Dried Soil Relates to Active Organic Pools. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 613–623. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies, R.L.; Walker, N.A.; Edwards, K.A.; Dainty, J. Is the Decline of Soil Microbial Biomass in Late Winter Coupled to Changes in the Physical State of Cold Soils? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, D.L.; Stein, J. Water-Movement into Seasonally Frozen Soils. Water Resour. Res. 1983, 19, 1547–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, P.; Woo, M.K. Wetting Front Advance and Freezing of Meltwater within a Snow Cover 1. Observations in the Canadian Arctic. Water Resour. Res. 1984, 20, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, D.L.; Hinkel, K.M.; Goering, D.J.; Hinzman, L.D.; Outcalt, S.I. Non-Conductive Heat Transfer Associated with Frozen Soils. Glob. Planet. Change 2001, 29, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, P. Theoretical and Experimental Effects of Cooling and Warming Velocity on Survival of Frozen and Thawed Cells. Cryobiology 1966, 2, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, P. Freezing of Living Cells: Mechanisms and Implications. Am. J. Physiol. 1984, 247, C125–C142. [Google Scholar]

- Deal, P.H. Freeze-Thaw Behaviour of a Moderately Halophilic Bacterium as a Function of Salt Concentration. Cryobiology 1970, 7, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikan, C.J.; Schimel, J.P.; Doyle, A.P. Temperature Controls of Microbial Respiration in Arctic Tundra Soils Above and Below Freezing. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panikov, N.S.; Flanagan, P.W.; Oechel, W.C.; Mastepanov, M.A.; Christensen, T.R. Microbial Activity in Soils Frozen to Below −39 °C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanueva, A.; Tuffin, M.; Cary, C.; Cowan, D.A. Molecular Adaptations to Psychrophily: The Impact of “Omic” Technologies. Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.L.; Walker, V.K. Selection of Low-Temperature Resistance in Bacteria and Potential Applications. Environ. Technol. 2010, 31, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oquist, M.G.; Sparrman, T.; Klemedtsson, L.; Drotz, S.H.; Grip, H.; Schleucher, J.; Nilsson, M. Water Availability Controls Microbial Temperature Responses in Frozen Soil CO2 Production. Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15, 2715–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilston, E.L.; Sparrman, T.; Oquist, M.G. Unfrozen Water Content Moderates Temperature Dependence of Sub-Zero Microbial Respiration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1396–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clein, J.S.; Schimel, J.P. Microbial Activity of Tundra and Taiga Soils at Subzero Temperatures. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1995, 27, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimel, J.P.; Mikan, C. Changing Microbial Substrate Use in Arctic Tundra Soils through a Freeze-Thaw Cycle. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, G.J.; Ping, C.L. Soil Organic Carbon and CO2 Respiration at Subzero Temperature in Soils of Arctic Alaska. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, D2. [Google Scholar]

- Schimel, J.P.; Bilbrough, C.; Welker, J.A. Increased Snow Depth Affects Microbial Activity and Nitrogen Mineralization in Two Arctic Tundra Communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, V.K.; Palmer, G.R.; Voordouw, G. Freeze-Thaw Tolerance and Clues to the Winter Survival of a Soil Community. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2006, 72, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.K.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Schimel, J.P. A Cross-Seasonal Comparison of Active and Total Bacterial Community Composition in Arctic Tundra Soil Using Bromodeoxyuridine Labeling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 287–295. [Google Scholar]

- Monson, R.K.; Lipson, D.L.; Burns, S.P.; Turnipseed, A.A.; Delany, A.C.; Williams, M.W.; Schmidt, S.K. Winter Forest Soil Respiration Controlled by Climate and Microbial Community Composition. Nature 2006, 439, 711–714. [Google Scholar]

- Schadt, C.W.; Martin, A.P.; Lipson, D.A.; Schmidt, S.K. Seasonal Dynamics of Previously Unknown Fungal Lineages in Tundra Soils. Science 2003, 301, 1359–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, D.A.; Schmidt, S.K. Seasonal Changes in an Alpine Soil Bacterial Community in the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2004, 70, 2867–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, D.A.; Schadt, C.W.; Schmidt, S.K. Changes in Soil Microbial Community Structure and Function in an Alpine Dry Meadow Following Spring Snow Melt. Microb. Ecol. 2002, 43, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, G. Climate Change and Soil Freezing Dynamics: Historical Trends and Projected Changes. Clim. Change 2008, 87, 421–434. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.Y.; Neufeld, J.D.; Walker, V.K.; Grogan, P. The Influence of Vegetation Type on the Dominant Soil Bacteria, Archaea, and Fungi in a Low Arctic Tundra Landscape. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 1756–1765. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.; Fierer, N.; Lauber, C.L.; Caporaso, J.G.; Knight, R.; Grogan, P. Soil Bacterial Diversity in the Arctic is not Fundamentally Different from that Found in Other Biomes. Environ. Microb. 2010, 12, 2998–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labine, C. Meteorology and Climatology of the Alexandra Fjord Lowland. In Ecology of a Polar Oasis, Alexandra Fiord, Ellesmere Island, Canada; Svoboda, J., Freedman, B., Eds.; Captus University Publications: Toronto, Canada, 1994; pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rayback, S.A.; Henry, G.H.R. Reconstruction of Summer Temperature for a Canadian High Arctic Site from Retrospective Analysis of the Dwarf Shrub, Cassiope tetragona. Arctic Antarct. Alp. Res. 2006, 38, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasser, M. Identification of Bacteria by Gas Chromatography of Cellular Fatty Acids; MIDI Technical note #101: Newark, DE, USA, 1990; revised 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Klose, S.; Acosta-Martinez, V.; Ajwa, H.A. Microbial Community Composition and Enzyme Activities in a Sandy Loam Soil after Fumigation with Methyl Bromide or Alternative Biocides. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Shah, V.; Walker, V.K. Perturbation of an Arctic Soil Microbial Community by Metal Nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 190, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, S.E.; Callaway, T.R.; Wolcott, R.D.; Sun, Y.; McKeehan, T.; Hagevoort, R.G.; Edrington, T.S. Evaluation of the Bacterial Diversity in the Feces of Cattle Using 16S rDNA Bacterial Tag-Encoded FLX Amplicon Pyrosequencing (bTEFAP). BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, H.D.; Plowes, R.; Sen, R.; Kellner, K.; Meyer, E.; Estrada, D.A.; Dowd, S.E.; Mueller, U.G. Bacterial Diversity in Solenopsis invicta and Solenopsis geminata Ant Colonies Characterized by 16S amplicon 454 Pyrosequencing. Microb. Ecol. 2011, 61, 821–831. [Google Scholar]

- Research and Testing Laboratory. Available online: http://www.researchandtesting.com/ (accessed on 17 December 2012).

- Gontcharova, V.; Youn, E.; Wolcott, R.D.; Hollister, E.B.; Gentry, T.J.; Dowd, S.E. Black Box Chimera Check (B2C2): A Windows-Based Software for Batch Depletion of Chimeras from Bacterial 16S rRNA Gene Datasets. Open Microbiol. J. 2010, 4, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.T.; Dowd, S.E.; Parry, N.M.; Galley, J.D.; Schauer, D.B.; Lyte, M. Stressor Exposure Disrupts Commensal Microbial Populations in the Intestines and Leads to Increased Colonization by Citrobacter rodentium. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 1509–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, S.E.; Zaragoza, J.; Rodriguez, J.R.; Oliver, M.J.; Payton, P.R. Windows.NET Network Distributed Basic local Alignment Search Toolkit (W.ND-BLAST). BMC Bioinformatics 2005, 6, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, J.R.; Wang, Q.; Cardenas, E.; Fish, J.; Chai, B.; Farris, R.J.; Kulam-Syed-Mohideen, A.S.; McGarrell, D.M.; Marsh, T.; Garrity, G.M.; et al. The Ribosomal Database Project: Improved Alignments and New Tools for rRNA Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D141–D145. [Google Scholar]

- Suutari, M.; Laakso, S. Microbial Fatty-Acids and Thermal Adaptation. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1994, 20, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, D.R.; Furlong, M.A.; Peacock, A.D.; White, D.C.; Coleman, D.C.; Whitman, W.B. Solirubrobacter pauli gen. nov., sp. nov., A Mesophilic Bacterium within the Rubrobacteridae Related to Common Soil Clones. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Na, J.R.; Lee, T.H.; Im, W.T.; Soung, N.K.; Yang, D.C. Solirubrobacter soli sp. nov., Isolated from Soil of a Ginseng Field. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 1453–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulino-Lima, I.G.; Azua-Bustos, A.; Vicuña, R.; González-Silva, C.; Salas, L.; Teixeira, L.; Rosado, A.; da Costa Leitao, A.A.; Lage, C. Isolation of UVC-tolerant Bacteria from the Hyperarid Atacama Desert, Chile. Microb. Ecol. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.; Luxton, T.; Kumar, N.; Shah, S.; Walker, V.K.; Shah, V. Assessing the Impact of Copper and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Soil: A Field Study. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42663. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, B.M. Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Refrigeration, Freezing and Freeze-Drying on Micro-Organisms. Soc. Appl. Bacteriol. Symp. Ser. 1984, 12, 45–75. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Griffith, M.; Patten, C.L.; Glick, B.R. Isolation and Characterization of an Antifreeze Protein with Ice Nucleation Activity from the Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacterium Pseudomonas putida GR12-2. Can. J. Microbiol. 1998, 44, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, J.A.; Fritsen, C.H. Semipurification and Ice Recrystallization Inhibition Activity of Ice-active Substances Associated with Antarctic Photosynthetic Organisms. Cryobiology 2001, 43, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.A.; Hill, P.J.; Dodd, C.E.R.; Laybourn-Parry, J. Demonstration of Antifreeze Protein Activity in Antarctic Lake Bacteria. Microbiology 2004, 150, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.L.; Frazer, C.; Cumming, B.F.; Nuin, P.A.S.; Walker, V.K. Cross-tolerance between Osmotic and Freeze-Thaw Stress in Microbial Assemblages from Temperate Lakes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 82, 405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Yergeau, E.; Kowalchuk, G.A. Responses of Antarctic Soil Microbial Communities and Associated Functions to Temperature and Freeze-Thaw Cycle Frequency. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 2223–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, L.; Peixoto, R.S.; Cury, J.C.; Sul, W.J.; Pellizari, V.H.; Tiedje, J.; Rosado, A.S. Bacterial Diversity in Rhizosphere Soil from Antarctic Vascular Plants of Admiralty Bay, Maritime Antarctica. ISME J. 2010, 4, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottos, E.M.; Vincent, W.F.; Greer, C.W.; Whyte, L.G. Prokaryotic Diversity of Arctic Ice Shelf Microbial Mats. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 950–966. [Google Scholar]

- Deslippe, J.R.; Egger, K.N.; Henry, G.H.R. Impacts of Warming and Fertilization on Nitrogen-Fixing Microbial Communities in the Canadian High Arctic. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005, 53, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Whitman, W.B.; Coleman, D.C.; Wiebe, W.J. Prokaryotes: The Unseen Majority. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6578–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.K.M.; Egger, K.N.; Henry, G.H.R. Long-Term Experimental Warming Alters Nitrogen-Cycling Communities but Site factors Remain the Primary Drivers of Community Structure in High Arctic Tundra Soils. ISME J. 2008, 2, 982–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, E.G.; Han, S.; Lanoil, B.D.; Henry, G.H.R.; Brummell, M.E.; Banerjee, S.; Siciliano, S.D. A High Arctic Soil Ecosystem Resists Long-Term Environmental Manipulations. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 3187–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimel, J.P.; Gulledge, J. Microbial Community Structure and Global Trace Gases. Glob. Change Biol. 1998, 4, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Siciliano, S.D. Evidence of High Microbial Abundance and Spatial Dependency in Three Arctic Soil Ecosystems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 2227–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, E.N. Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 1963, 20, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, N.; Grogan, P.; Chu, H.; Christiansen, C.T.; Walker, V.K. The Effect of Freeze-Thaw Conditions on Arctic Soil Bacterial Communities. Biology 2013, 2, 356-377. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology2010356

Kumar N, Grogan P, Chu H, Christiansen CT, Walker VK. The Effect of Freeze-Thaw Conditions on Arctic Soil Bacterial Communities. Biology. 2013; 2(1):356-377. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology2010356

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Niraj, Paul Grogan, Haiyan Chu, Casper T. Christiansen, and Virginia K. Walker. 2013. "The Effect of Freeze-Thaw Conditions on Arctic Soil Bacterial Communities" Biology 2, no. 1: 356-377. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology2010356

APA StyleKumar, N., Grogan, P., Chu, H., Christiansen, C. T., & Walker, V. K. (2013). The Effect of Freeze-Thaw Conditions on Arctic Soil Bacterial Communities. Biology, 2(1), 356-377. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology2010356