The Genetic Landscape of Androgenetic Alopecia: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Genetic Architecture of AGA

2.1. Genome-Wide Association Studies

2.2. Key Biological Pathways

| Gene/Locus | SNP or Variant | Population | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| AR [23] | rs6152 | European mixed ancestry male populations | Increased risk |

| AR/EDA2R locus [23,24,28,29] | rs12558842 | European mixed ancestry male population; Mixed ethnicity mixed sex; German male population | Increased risk |

| Xq12 locus [30] | rs1041668 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk |

| 20p11 locus [30] | rs1160312 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk |

| rs6113491 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk | |

| WNT10A intronic region [24] | rs7349332 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk |

| SUCNR1 and MBNL1 intergenic [24] | rs7648585 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk |

| EBF1 [23,24] | rs929626 | European mixed ancestry male population | Reduced risk [22,29] |

| rs1081073 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk [29] | |

| SSPN and ITPR2 intergenic [24] | rs9668810 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk |

| rs7975017 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk | |

| HDAC9 [28,31] | rs2073963 | German male population; European mixed ancestry mixed sex population | Increased risk |

| TARDBP [23,31] | rs12565727 | European mixed ancestry male population; European mixed ancestry mixed sex population | Reduced risk [22]; Increased risk [30] |

| AUTS2 [31] | rs6945541 | European mixed ancestry mixed sex population | Increased risk |

| PAX1 and FOXA2 intergenic [31,32] | rs6047844 | European mixed ancestry mixed sex population, Korean males | Increased risk |

| PTGES2 [33] | rs13283456 | Mixed ethnicity and mixed sex population | Increased risk |

| SRD5A2 [33] | rs523349 | Mixed ethnicity and mixed sex population | Increased risk |

| COL1A1 [33] | rs1800012 | Mixed ethnicity and mixed sex population | Increased risk |

| ACE [33] | rs4343 | Mixed ethnicity and mixed sex population | Increased risk |

| PTGFR [33] | rs10782665 | Mixed ethnicity and mixed sex population | Increased risk |

| PTGDR2 [33] | rs533116 | Mixed male and female population | Increased risk |

| rs545659 | Mixed ethnicity and mixed sex population | Increased risk | |

| CRABP2 [33] | rs12724719 | Mixed ethnicity and mixed sex population | Increased risk |

| Not known [13] | rs11010734 | Korean male population | Increased risk |

| PANK1 and KIF20B intergenic [13] | rs2420640 | Korean male population | Increased risk |

| 2q31.1 locus [14] | rs13405699 | Han Chinese male population | Increased risk |

| FGF5 [12] | rs982804 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk |

| IRF4 [12] | rs12203592 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk |

| DKK2 [12,15] | rs145945174 | European mixed ancestry male population | Increased risk [12] |

| rs116494345 | African male population | Increased risk [15] | |

| SLC301A10 [15] | rs143451223 | African male population | Increased risk |

| FZD1 [32] | rs2163085 | Korean female population | Increased risk |

| GJC1 [32] | rs4793158 | Korean female population | Increased risk |

2.3. Sex Differences

2.4. Ancestry Considerations

| Author | Select Genes/Loci | Study Type | Sample Size (Cases/Total N) | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambra et al. 2025 [30] | Xq12 locus, 20p11 locus | Genetic association study | 104 cases/ 212 N | Moderate—single study with a relatively small sample, associations adjusted for confounders, but no replication cohort or meta-analysis included |

| Brockschmidt et al. 2011 [28] | AR/EDA2R locus, HDAC9 | GWAS | 581 cases/ 1198 N | Moderate to strong—replicated in independent sample; supported by fine-mapping, family-based TDT analysis, and tissue expression studies; effect sizes modest |

| Francès et al. 2024 [33] | PTGES2, SRD5A2, COL1A1, ACE, PTGFR, PTGDR2, CRABP2 | Candidate SNP association study | 26,607/ 26,607 N | Low to moderate—Large sample size improves statistical power, However, restricted to predefined candidate SNPs. Associations reported at nominal significance thresholds (p < 0.05), not genome-wide significance. Absence of non-AGA controls limits inference about disease susceptibility |

| Heilmann et al. 2013 [24] | WNT10A, SUCNR1 and MBNL1 intergenic, EBF1, SSPN and ITPR2 intergenic | Replication of meta-analysis | 2759/5420 N (plus previous meta-analysis) | Strong—genome-wide significant loci confirmed, multi-cohort replication, robust QC and statistical methods, supported by expression analysis in human hair follicles |

| Heilmann-Heimbach et al. 2017 [12] | FGF5, IRF4, DKK2 | GWAS | 10,846/ 26,607 N | Very strong—high-quality genetic evidence. Genome-wide significance threshold applied (p < 5 × 10−8) Extensive quality control, imputation, and heterogeneity testing. Replication across multiple independent cohorts. Polygenicity formally assessed and population stratification ruled out. Functional follow-up (eQTLs, enhancer enrichment, pathway analyses) |

| Henne et al. 2023 [44] | EDA2R, WNT10A | Exome wide association | 72,469/ 72,469 N | Strong—very large, population-based exome sequencing study; combines single-variant and gene-based tests; confirms known genes and identifies novel rare variant associations; results are further integrated with PRS for risk modeling |

| Janivara et al. 2025 [15] | DKK2, SLC301A10 | GWAS | 2136/ 2136 N | Moderate—limited by moderate sample size for detecting genome-wide significance and by reliance on self-reported baldness |

| Kim et al. 2022 [13] | PANK1 and KIF20B intergenic | GWAS | 275/421 N | Low to moderate—Single-center, hospital-based cohort, modest sample size with limited statistical power, GWAS findings reach suggestive significance rather than conventional genome-wide significance, replication signals largely nominal (p < 0.05) |

| Lee et al. 2024 [32] | PAX1 and FOXA2 intergenic, FZD1, GJC1 | GWAS | 545/1004 N | Moderate—Single-cohort GWAS with modest sample size, includes replication of known loci, limited power relative to large meta-analyses |

| Li et al. 2012 [31] | HDAC9, TARDBP, AUTS2, PAX1 and FOXA2 intergenic | Meta-analysis of GWAS | 3891/ 12,806 N | Strong—Large-scale GWAS meta-analysis across multiple cohorts, genome-wide significant loci identified (p < 5 × 10−8), replication and follow-up in independent samples, multiple analyses including risk score and disease association |

| Li et al. 2024 [14] | 2q31.1 | Candidate SNP replication | 499/1988 N | Moderate—Well-powered replication of known GWAS loci, but only 1 SNP reached significance after multiple testing, limited by relatively small sample size |

| Marcińska et al. 2015 [23] | AR, AR/EDA2R locus, EBF1, TARDBP | Candidate SNP association study | 476/605 N | Moderate—validated in independent test set, moderate sample size |

| Zhuo et al. 2012 [29] | AR/EDA2R locus | Meta-analysis | 2074/3189 N | Moderate—synthesizes multiple studies, limited by small number of included studies (n = 8) and some heterogeneity |

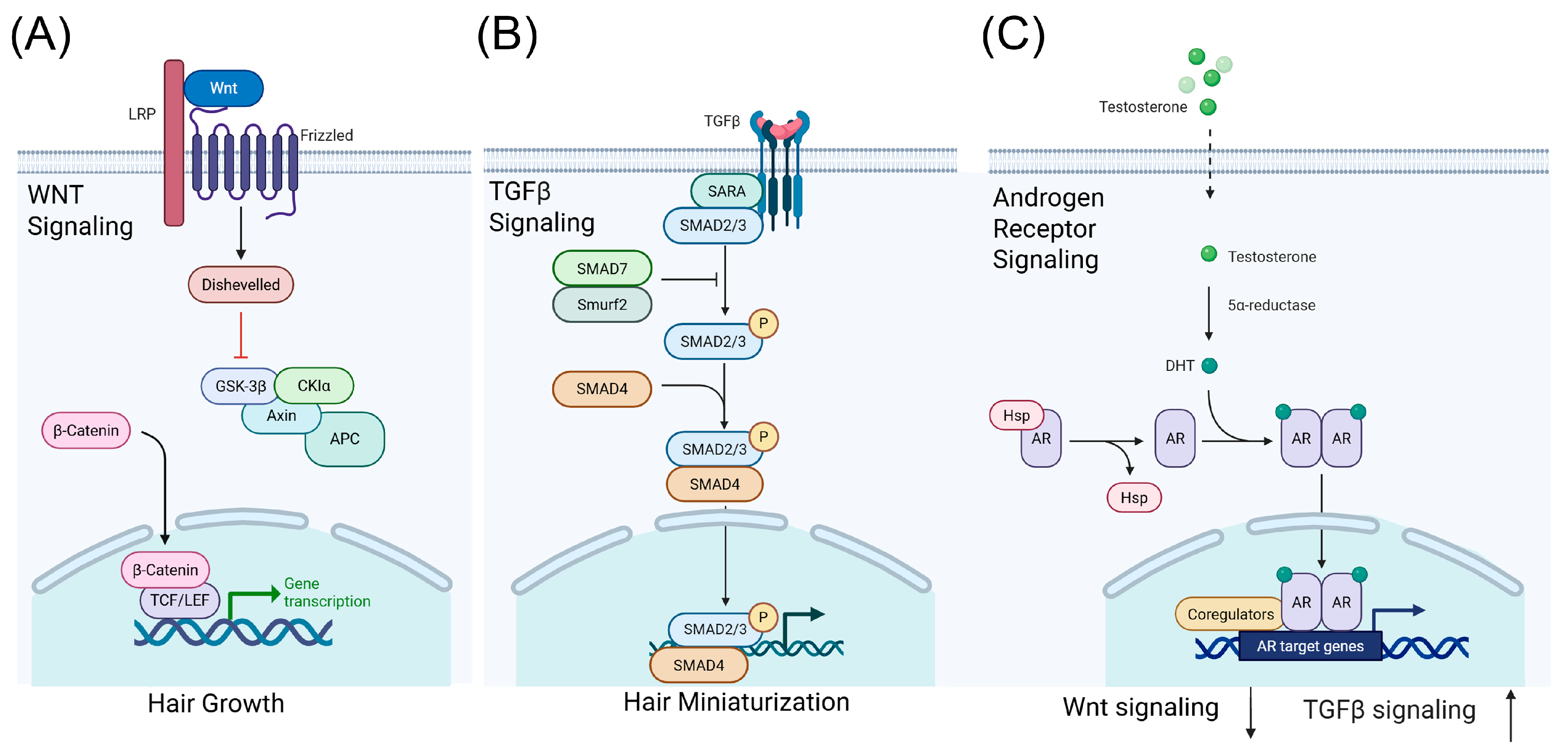

3. Genetic Associations and Biological Mechanisms

3.1. Functional Annotation of GWAS Loci

3.2. Insights from Single-Cell and Multi-Omics Studies

3.3. Clinical Significance of Biological Mechanisms

4. Pharmacogenetics and Clinical Implications

4.1. Finasteride and Dutasteride

4.2. Minoxidil

4.3. Genetics and Adverse Effects

4.4. Other Therapeutic Approaches and Pharmacogenetic Considerations

5. Future Directions

5.1. Research Needs

5.2. Prospective Studies

5.3. Therapeutic Potential

6. Conclusions

7. Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGA | Androgenetic alopecia |

| APC | Adenomatous polyposis coli |

| AR | Androgen receptor |

| CKIα | Casein kinase I alpha |

| DHT | Dihydrotestosterone |

| DKK2 | Dickkopf-related protein 2 |

| eQTL | Expression quantitative trait loci |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| FPHL | Female-pattern hair loss |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association studies |

| HSP | Heat shock protein |

| P | Phosphorylation |

| SARA | Smad anchor for receptor activation |

| SMAD | Suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| TCF/LEF | T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-beta |

| TWAS | Transcriptome-wide association study |

References

- Devjani, S.; Ezemma, O.; Kelley, K.J.; Stratton, E.; Senna, M. Androgenetic Alopecia: Therapy Update. Drugs 2023, 83, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lolli, F.; Pallotti, F.; Rossi, A.; Fortuna, M.C.; Caro, G.; Lenzi, A.; Sansone, A.; Lombardo, F. Androgenetic Alopecia: A Review. Endocrine 2017, 57, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Jacobo, L.; Villarreal-Villarreal, C.D.; Ortiz-López, R.; Ocampo-Candiani, J.; Rojas-Martínez, A. Genetic and Molecular Aspects of Androgenetic Alopecia. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2018, 84, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Wang, T.; Economopoulos, V. Epidemiological Landscape of Androgenetic Alopecia in the US: An All of Us Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paus, R.; Cotsarelis, G. The Biology of Hair Follicles. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierard-Franchimont, C.; Piérard, G.E. Teloptosis, a Turning Point in Hair Shedding Biorhythms. Dermatology 2001, 203, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, S.; Itami, S. Molecular Basis of Androgenetic Alopecia: From Androgen to Paracrine Mediators through Dermal Papilla. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2011, 61, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyholt, D.R.; Gillespie, N.A.; Heath, A.C.; Martin, N.G. Genetic Basis of Male Pattern Baldness. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 121, 1561–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexbye, H.; Petersen, I.; Iachina, M.; Mortensen, J.; Mcgue, M.; Vaupel, J.W.; Christensen, K. Hair Loss Among Elderly Men: Etiology and Impact on Perceived Age. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2005, 60, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.B.; Yuan, X.; Geller, F.; Waterworth, D.; Bataille, V.; Glass, D.; Song, K.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P.; Aben, K.K.H.; et al. Male-Pattern Baldness Susceptibility Locus at 20p11. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1282–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirastu, N.; Joshi, P.K.; De Vries, P.S.; Cornelis, M.C.; McKeigue, P.M.; Keum, N.; Franceschini, N.; Colombo, M.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Spiliopoulou, A.; et al. GWAS for Male-Pattern Baldness Identifies 71 Susceptibility Loci Explaining 38% of the Risk. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann-Heimbach, S.; Herold, C.; Hochfeld, L.M.; Hillmer, A.M.; Nyholt, D.R.; Hecker, J.; Javed, A.; Chew, E.G.Y.; Pechlivanis, S.; Drichel, D.; et al. Meta-Analysis Identifies Novel Risk Loci and Yields Systematic Insights into the Biology of Male-Pattern Baldness. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, J.E.; Yu, S.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.R.; Choi, M.S.; Kim, M.H.; Hong, K.W.; Park, B.C. The First Broad Replication Study of SNPs and a Pilot Genome-Wide Association Study for Androgenetic Alopecia in Asian Populations. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 6174–6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Liang, B.; Xiao, F.L.; Zhou, F.S.; Zheng, X.D.; Yang, S.; Zhang, X.J. Association Study Reveals a Susceptibility Locus with Male Pattern Baldness in the Han Chinese Population. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1438375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janivara, R.; Hazra, U.; Pfennig, A.; Harlemon, M.; Kim, M.S.; Eaaswarkhanth, M.; Chen, W.C.; Ogunbiyi, A.; Kachambwa, P.; Petersen, L.N.; et al. Uncovering the Genetic Architecture and Evolutionary Roots of Androgenetic Alopecia in African Men. Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. 2025, 6, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmer, A.M.; Flaquer, A.; Hanneken, S.; Eigelshoven, S.; Kortüm, A.K.; Brockschmidt, F.F.; Golla, A.; Metzen, C.; Thiele, H.; Kolberg, S.; et al. Genome-Wide Scan and Fine-Mapping Linkage Study of Androgenetic Alopecia Reveals a Locus on Chromosome 3q26. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilmann, S.; Brockschmidt, F.F.; Hillmer, A.M.; Hanneken, S.; Eigelshoven, S.; Ludwig, K.U.; Herold, C.; Mangold, E.; Becker, T.; Kruse, R.; et al. Evidence for a Polygenic Contribution to Androgenetic Alopecia. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, M.; He, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, L.; Xiong, X. Cellular Senescence: Ageing and Androgenetic Alopecia. Dermatology 2023, 239, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Song, J.; Lee, Y.; Jeong, Y.; Jang, W. Prioritizing Susceptibility Genes for the Prognosis of Male-Pattern Baldness with Transcriptome-Wide Association Study. Hum. Genom. 2024, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henne, S.K.; Aldisi, R.; Sivalingam, S.; Hochfeld, L.M.; Borisov, O.; Krawitz, P.M.; Maj, C.; Nöthen, M.M.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S. Analysis of 72,469 UK Biobank Exomes Links Rare Variants to Male-Pattern Hair Loss. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.A.; Stebbing, M.; Harrap, S.B. Polymorphism of the Androgen Receptor Gene Is Associated with Male Pattern Baldness. J. Investig. Dermol. 2001, 116, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmer, A.M.; Hanneken, S.; Ritzmann, S.; Becker, T.; Freudenberg, J.; Brockschmidt, F.F.; Flaquer, A.; Freudenberg-Hua, Y.; Jamra, R.A.; Metzen, C.; et al. Genetic Variation in the Human Androgen Receptor Gene Is the Major Determinant of Common Early-Onset Androgenetic Alopecia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 77, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińska, M.; Pośpiech, E.; Abidi, S.; Andersen, J.D.; Van Den Berge, M.; Carracedo, Á.; Eduardoff, M.; Marczakiewicz-Lustig, A.; Morling, N.; Sijen, T.; et al. Evaluation of DNA Variants Associated with Androgenetic Alopecia and Their Potential to Predict Male Pattern Baldness. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilmann, S.; Kiefer, A.K.; Fricker, N.; Drichel, D.; Hillmer, A.M.; Herold, C.; Tung, J.Y.; Eriksson, N.; Redler, S.; Betz, R.C.; et al. Androgenetic Alopecia: Identification of Four Genetic Risk Loci and Evidence for the Contribution of WNT Signaling to Its Etiology. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensuksira, S.; Surinlert, P.; Krajarng, A.; Nualsanit, T.; Payuhakrit, W.; Panpinyaporn, P.; Khumsri, W.; Thanasarnaksorn, W.; Suwanchinda, A.; Hongeng, S.; et al. Progenitor Cell Dynamics in Androgenetic Alopecia: Insights from Spatially Resolved Transcriptomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Pu, W.; Liu, J.; Shi, X.; Ma, Y.; et al. Insights into Male Androgenetic Alopecia Using Comparative Transcriptome Profiling: Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 and Wnt/β-Catenin Signalling Pathways. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 187, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibino, T.; Nishiyama, T. Role of TGF-Β2 in the Human Hair Cycle. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2004, 35, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockschmidt, F.F.; Heilmann, S.; Ellis, J.A.; Eigelshoven, S.; Hanneken, S.; Herold, C.; Moebus, S.; Alblas, M.A.; Lippke, B.; Kluck, N.; et al. Susceptibility Variants on Chromosome 7p21.1 Suggest HDAC9 as a New Candidate Gene for Male-Pattern Baldness. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 165, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, F.L.; Xu, W.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Z.L.; Zhao, J.Y. Androgen Receptor Gene Polymorphisms and Risk for Androgenetic Alopecia: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2012, 37, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambra, R.; Mastroeni, S.; Manca, S.; Mannooranparampil, T.J.; Virgili, F.; Marzani, B.; Pinto, D.; Fortes, C. Genetic Variants and Lifestyle Factors in Androgenetic Alopecia Patients: A Case–Control Study of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Their Contribution to Baldness Risk. Nutrients 2025, 17, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Brockschmidt, F.F.; Kiefer, A.K.; Stefansson, H.; Nyholt, D.R.; Song, K.; Vermeulen, S.H.; Kanoni, S.; Glass, D.; Medland, S.E.; et al. Six Novel Susceptibility Loci for Early-Onset Androgenetic Alopecia and Their Unexpected Association with Common Diseases. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Choi, J.E.; Ha, J.; Kim, Y.; Lee, C.; Hong, K.W. Genetic Differences between Male and Female Pattern Hair Loss in a Korean Population. Life 2024, 14, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francès, M.P.; Vila-Vecilla, L.; Russo, V.; Caetano Polonini, H.; de Souza, G.T. Utilising SNP Association Analysis as a Prospective Approach for Personalising Androgenetic Alopecia Treatment. Dermatol. Ther. 2024, 14, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redler, S.; Messenger, A.G.; Betz, R.C. Genetics and Other Factors in the Aetiology of Female Pattern Hair Loss. Exp. Dermatol. 2017, 26, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redler, S.; Brockschmidt, F.F.; Tazi-Ahnini, R.; Drichel, D.; Birch, M.P.; Dobson, K.; Giehl, K.A.; Herms, S.; Refke, M.; Kluck, N.; et al. Investigation of the Male Pattern Baldness Major Genetic Susceptibility Loci AR/EDA2R and 20p11 in Female Pattern Hair Loss. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 166, 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herskovitz, I.; Tosti, A. Female Pattern Hair Loss. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 11, e9860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daunton, A.; Harries, M.; Sinclair, R.; Paus, R.; Tosti, A.; Messenger, A. Chronic Telogen Effluvium: Is It a Distinct Condition? A Systematic Review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2023, 24, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwaihyd, R.; Redler, S.; Heilmann, S.; Drichel, D.; Wolf, S.; Birch, P.; Dobson, K.; Lutz, G.; Giehl, K.A.; Kruse, R.; et al. Investigation of Four Novel Male Androgenetic Alopecia Susceptibility Loci: No Association with Female Pattern Hair Loss. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2014, 306, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.Y.; Chen, J.Y.F.; Hsu, W.L.; Yu, S.; Chen, W.C.; Chiu, S.H.; Yang, H.R.; Lin, S.Y.; Wu, C.Y. Female Pattern Hair Loss: An Overview with Focus on the Genetics. Genes 2023, 14, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.-J.; Kim, J.-S.; Myung, J.-W.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, J.-W. Analysis of Genetic Polymorphisms of Steroid 5a-Reductase Type 1 and 2 Genes in Korean Men with Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2003, 31, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Yang, C.; Zuo, X.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Zhou, F.; Cheng, H.; Zheng, X.; Chen, G.; et al. Genetic Variants at 20p11 Confer Risk to Androgenetic Alopecia in the Chinese Han Population. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Lee, H.J. Characteristics of Androgenetic Alopecia in Asian. Ann. Dermatol. 2012, 24, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otberg, N.; Finner, A.M.; Shapiro, J. Androgenetic Alopecia. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 36, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henne, S.K.; Nöthen, M.M.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S. Male-Pattern Hair Loss: Comprehensive Identification of the Associated Genes as a Basis for Understanding Pathophysiology. Med. Genet. 2023, 35, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T.; Song, L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, C.; Yang, J. From Genetic Associations to Genes: Methods, Applications, and Challenges. Trends Genet. 2024, 40, 642–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gay, N.R.; Gloudemans, M.; Antonio, M.L.; Abell, N.S.; Balliu, B.; Park, Y.; Martin, A.R.; Musharoff, S.; Rao, A.S.; Aguet, F.; et al. Impact of Admixture and Ancestry on EQTL Analysis and GWAS Colocalization in GTEx. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Gopalan, S.; Yuan, D.; Conti, D.V.; Pasaniuc, B.; Gusev, A.; Mancuso, N. Multi-Ancestry Fine-Mapping Improves Precision to Identify Causal Genes in Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 109, 1388–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Yu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, P.; Peng, Y.; Yan, X.; Li, Y.; Hua, P.; Li, Q.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomics Reveals Lineage Trajectory of Human Scalp Hair Follicle and Informs Mechanisms of Hair Graying. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Grzenda, A.; Allison, T.F.; Rawnsley, J.; Balin, S.J.; Sabri, S.; Plath, K.; Lowry, W.E. Defining Transcriptional Signatures of Human Hair Follicle Cell States. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 764–773.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Park, J.; Abudureyimu, G.; Kim, M.H.; Shim, J.S.; Jang, K.T.; Kwon, E.J.; Jang, H.S.; Yeo, E.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Comparative Spatial Transcriptomic and Single-Cell Analyses of Human Nail Units and Hair Follicles Show Transcriptional Similarities between the Onychodermis and Follicular Dermal Papilla. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 3146–3157.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober-Reynolds, B.; Wang, C.; Ko, J.M.; Rios, E.J.; Aasi, S.Z.; Davis, M.M.; Oro, A.E.; Greenleaf, W.J. Integrated Single-Cell Chromatin and Transcriptomic Analyses of Human Scalp Identify Gene-Regulatory Programs and Critical Cell Types for Hair and Skin Diseases. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, A.; Motavaf, M.; Raza, D.; McLure, A.J.; Osei-Opare, K.D.; Bordone, L.A.; Gru, A.A. Revolutionary Approaches to Hair Regrowth: Follicle Neogenesis, Wnt/ß-Catenin Signaling, and Emerging Therapies. Cells 2025, 14, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Fan, Z.; Huang, W.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B.; Zhu, D.; Dai, D.; Zhang, J.; Le, D.; et al. Retinoic Acid Drives Hair Follicle Stem Cell Activation via Wnt/β-Catenin Signalling in Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntshingila, S.; Oputu, O.; Arowolo, A.T.; Khumalo, N.P. Androgenetic Alopecia: An Update. JAAD Int. 2023, 13, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, V.M.; Severi, G.; Padilla, E.J.D.; Morris, H.A.; Tilley, W.D.; Southey, M.C.; English, D.R.; Sutherland, R.L.; Hopper, J.L.; Boyle, P.; et al. 5α-Reductase Type 2 Gene Variant Associations with Prostate Cancer Risk, Circulating Hormone Levels and Androgenetic Alopecia. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 120, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Song, S.; Gao, Z.; Wu, J.; Ma, J.; Cui, Y. The Efficacy and Safety of Dutasteride Compared with Finasteride in Treating Men with Androgenetic Alopecia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.C.; Chapman, L.W.; Mesinkovska, N.A. The Efficacy and Use of Finasteride in Women: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2019, 58, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, A.; Rundegren, J. Minoxidil: Mechanisms of Action on Hair Growth. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 150, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, A.; Castano, J.A.; McCoy, J.; Bermudez, F.; Lotti, T. Novel Enzymatic Assay Predicts Minoxidil Response in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia. Dermatol. Ther. 2014, 27, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Cauhe, J.; Vaño-Galvan, S.; Mehta, N.; Hermosa-Gelbard, A.; Ortega-Quijano, D.; Buendia-Castaño, D.; Fernández-Nieto, D.; Porriño-Bustamante, M.; Saceda-Corralo, D.; Pindado-Ortega, C.; et al. Hair Follicle Sulfotransferase Activity and Effectiveness of Oral Minoxidil in Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 3767–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaboardi, H.; Russo, V.; Vila-Vecilla, L.; Patel, V.; De Souza, G.T. 26-SNP Panel Aids Guiding Androgenetic Alopecia Therapy and Provides Insight into Mechanisms of Action. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchin, E.; De Mattia, E.; Mazzon, G.; Cauci, S.; Trombetta, C.; Toffoli, G. A Pharmacogenetic Survey of Androgen Receptor (CAG)n and (GGN)n Polymorphisms in Patients Experiencing Long Term Side Effects after Finasteride Discontinuation. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2014, 29, e310–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauci, S.; Chiriacò, G.; Cecchin, E.; Toffoli, G.; Xodo, S.; Stinco, G.; Trombetta, C. Androgen Receptor (AR) Gene (CAG)n and (GGN)n Length Polymorphisms and Symptoms in Young Males with Long-Lasting Adverse Effects After Finasteride Use Against Androgenic Alopecia. Sex. Med. 2017, 5, e61–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Chapoy, D.; Cruz-Arroyo, F.J.; Ancer-Leal, F.D.; Rodriguez-Leal, R.A.; Camacho-Zamora, B.D.; Guzman-Sanchez, D.A.; Espinoza-Gonzalez, N.A.; Martinez-Jacobo, L.; Marino-Martinez, I.A. Pilot Study: Genetic Distribution of AR, FGF5, SULT1A1 and CYP3A5 Polymorphisms in Male Mexican Population with Androgenetic Alopecia. Int. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Genet. 2022, 13, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Faghihi, G.; Iraji, F.; Siadat, A.H.; Saber, M.; Jelvan, M.; Hoseyni, M.S. Comparison between “5% Minoxidil plus 2% Flutamide” Solution vs. “5% Minoxidil” Solution in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 4447–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleissa, M. The Efficacy and Safety of Oral Spironolactone in the Treatment of Female Pattern Hair Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e43559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed Jafari, S.M.; Heidemeyer, K.; Hunger, R.E.; de Viragh, P.A. Safety of Antiandrogens for the Treatment of Female Androgenetic Alopecia with Respect to Gynecologic Malignancies. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, C.; Minty, I.; Dsouza, A.; Wong, Y.Y.; Mukhopadhyay, I.; Nagarajan, V.; Rupra, R.; Charles, W.N.; Khajuria, A. The Role of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Androgenetic Alopecia: A Systematic Review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, S.M.; Vattigunta, M.; Kelly, C.; Eber, A. Low-Level Laser and LED Therapy in Alopecia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dermatol. Surg. 2025, 51, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, S.M.; AlSalman, S.A.; Nguyen, B.; Tosti, A. Botulinum Toxin in the Treatment of Hair and Scalp Disorders: Current Evidence and Clinical Applications. Toxins 2025, 17, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queen, D.; Avram, M.R. Hair Transplantation: State of the Art. Dermatol. Surg. 2025, 51, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhurat, R.; Daruwalla, S.; Pai, S.; Kovacevic, M.; McCoy, J.; Shapiro, J.; Sinclair, R.; Vano-Galvan, S.; Goren, A. SULT1A1 (Minoxidil Sulfotransferase) Enzyme Booster Significantly Improves Response to Topical Minoxidil for Hair Regrowth. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Desai, N.; McCoy, J.; Goren, A. Sulfotransferase Activity in Plucked Hair Follicles Predicts Response to Topical Minoxidil in the Treatment of Female Androgenetic Alopecia. Dermatol. Ther. 2014, 27, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, T.; Wan, S.; Xiong, R.; Jin, S.; Dai, Y.; Guan, C. Application of Multi-Omics Techniques to Androgenetic Alopecia: Current Status and Perspectives. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 2623–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Pérez, L.; Tornero-Esteban, P.; López-Bran, E. Clinical and Preclinical Approach in AGA Treatment: A Review of Current and New Therapies in the Regenerative Field. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrauszka, K.; Bergler-Czop, B. Sulfotransferase SULT1A1 Activity in Hair Follicle, a Prognostic Marker of Response to the Minoxidil Treatment in Patients with Androgenetic Alopecia: A Review. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2022, 39, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, A.; Caro, G. Efficacy of the Association of Topical Minoxidil and Topical Finasteride Compared to Their Use in Monotherapy in Men with Androgenetic Alopecia: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled, Assessor Blinded, 3-Arm, Pilot Trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchonwanit, P.; Iamsumang, W.; Rojhirunsakool, S. Efficacy of Topical Combination of 0.25% Finasteride and 3% Minoxidil Versus 3% Minoxidil Solution in Female Pattern Hair Loss: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Study. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, B. The Efficacy and Safety of Finasteride Combined with Topical Minoxidil for Androgenetic Alopecia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2020, 44, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gupta, A.K.; Dennis, D.J.; Economopoulos, V.; Piguet, V. The Genetic Landscape of Androgenetic Alopecia: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Biology 2026, 15, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020192

Gupta AK, Dennis DJ, Economopoulos V, Piguet V. The Genetic Landscape of Androgenetic Alopecia: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Biology. 2026; 15(2):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020192

Chicago/Turabian StyleGupta, Aditya K., Daniel J. Dennis, Vasiliki Economopoulos, and Vincent Piguet. 2026. "The Genetic Landscape of Androgenetic Alopecia: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives" Biology 15, no. 2: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020192

APA StyleGupta, A. K., Dennis, D. J., Economopoulos, V., & Piguet, V. (2026). The Genetic Landscape of Androgenetic Alopecia: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Biology, 15(2), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020192