Establishment and Polymorphism Analysis of SNP Markers in the Gynogenic Blunt Snout Bream

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Gynogenesis and Fish Rearing

2.3. Screening of the Transcriptome SNP

2.4. Preparation of the DNA Samples

2.5. Verification of the SNP Marker Sites

2.6. SNP Marker Function Analysis

2.7. Genetic Polymorphism Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

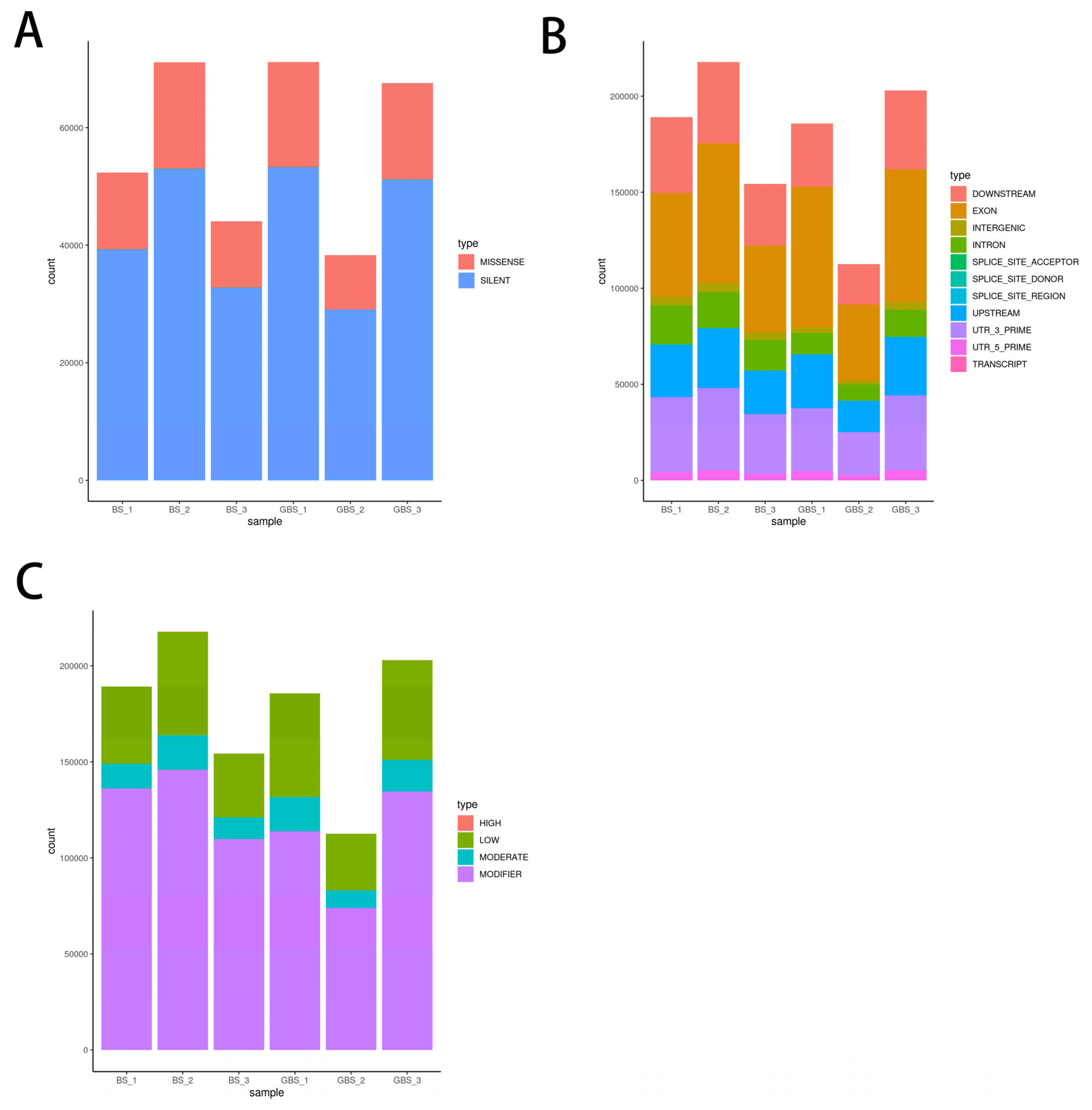

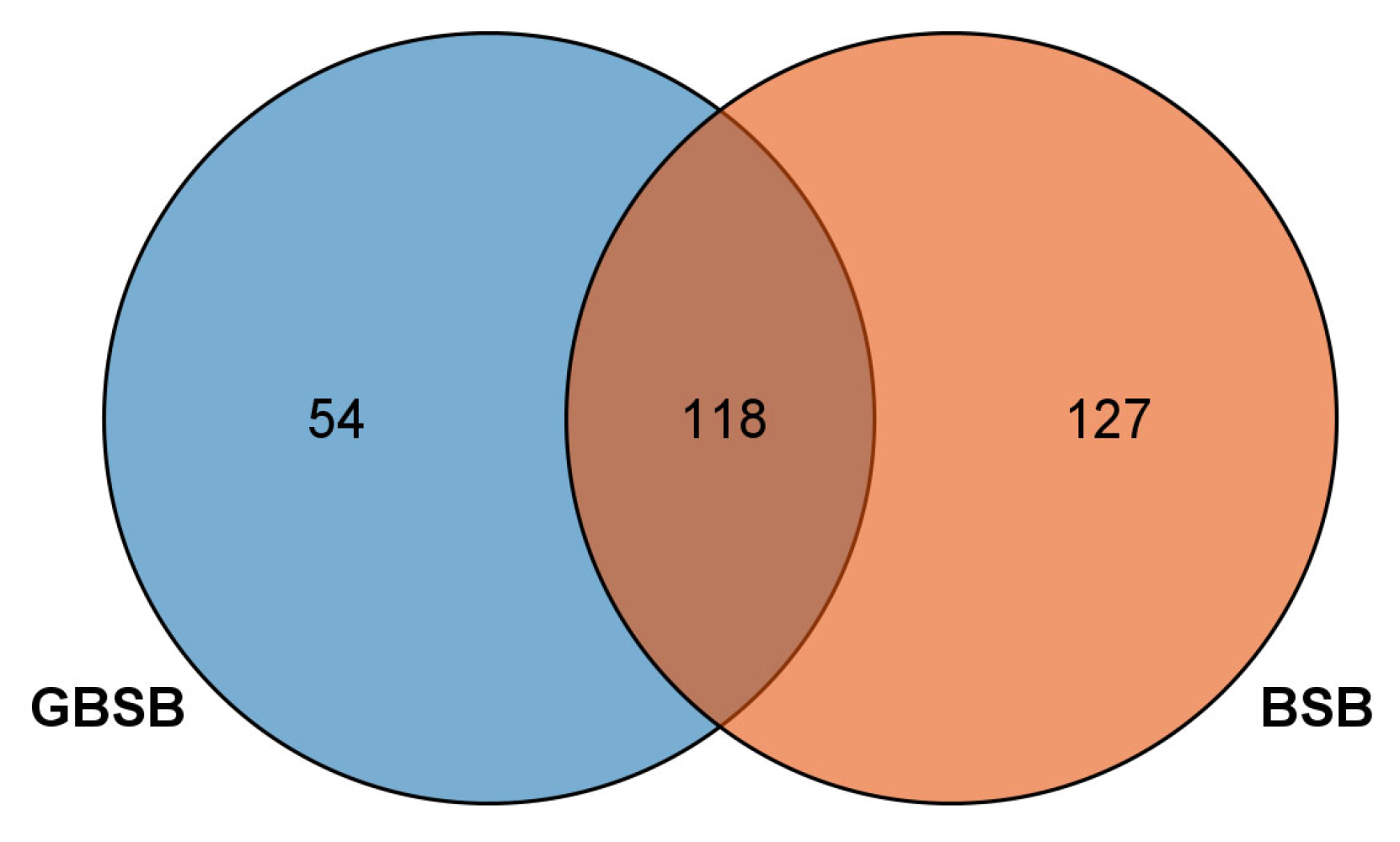

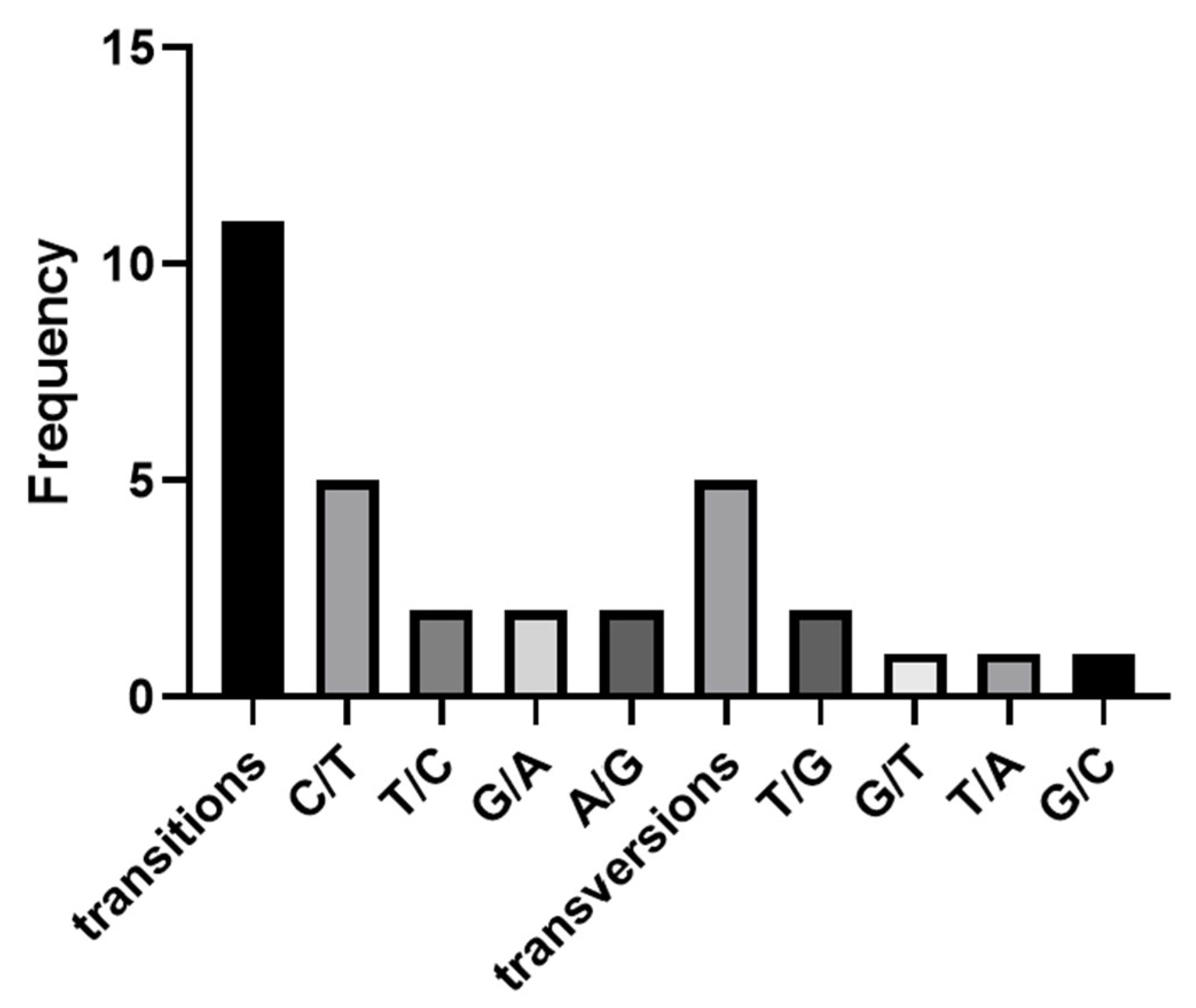

3.1. Analysis of Polymorphic Sites and Screening of Core SNP Sites in Transcriptome

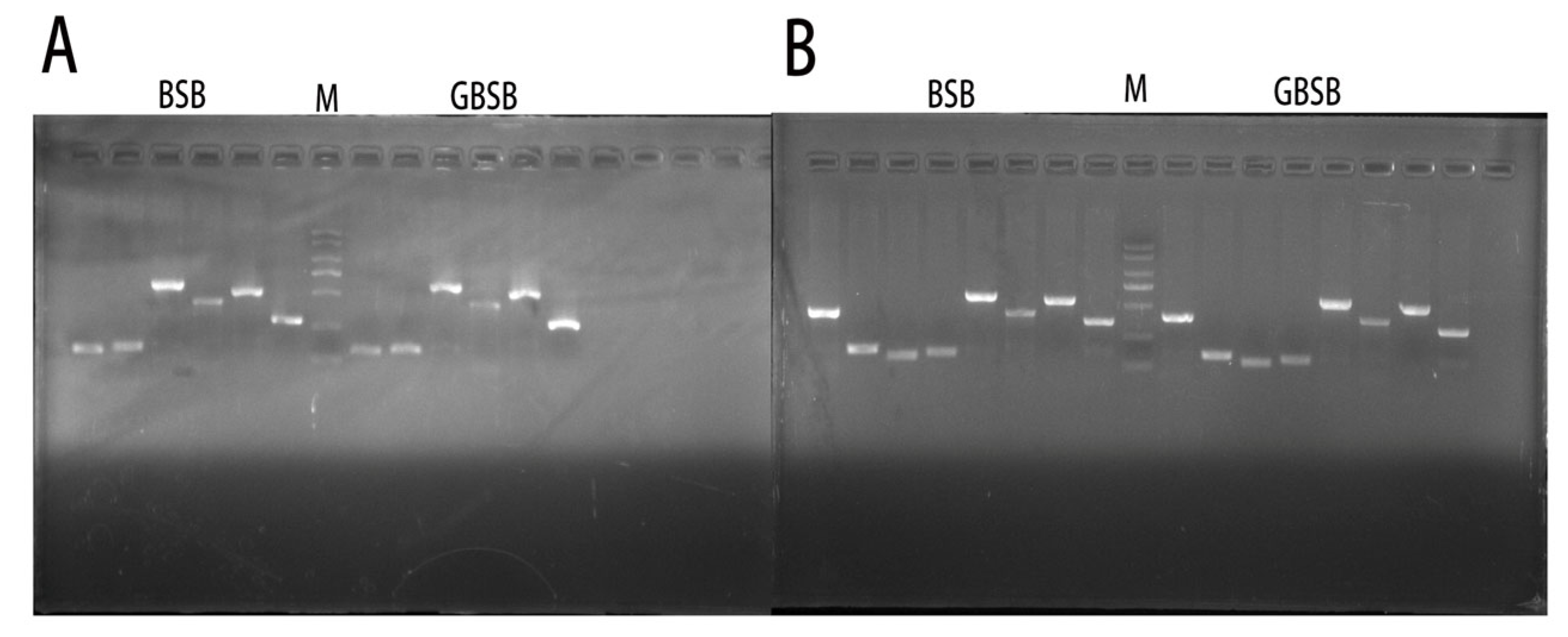

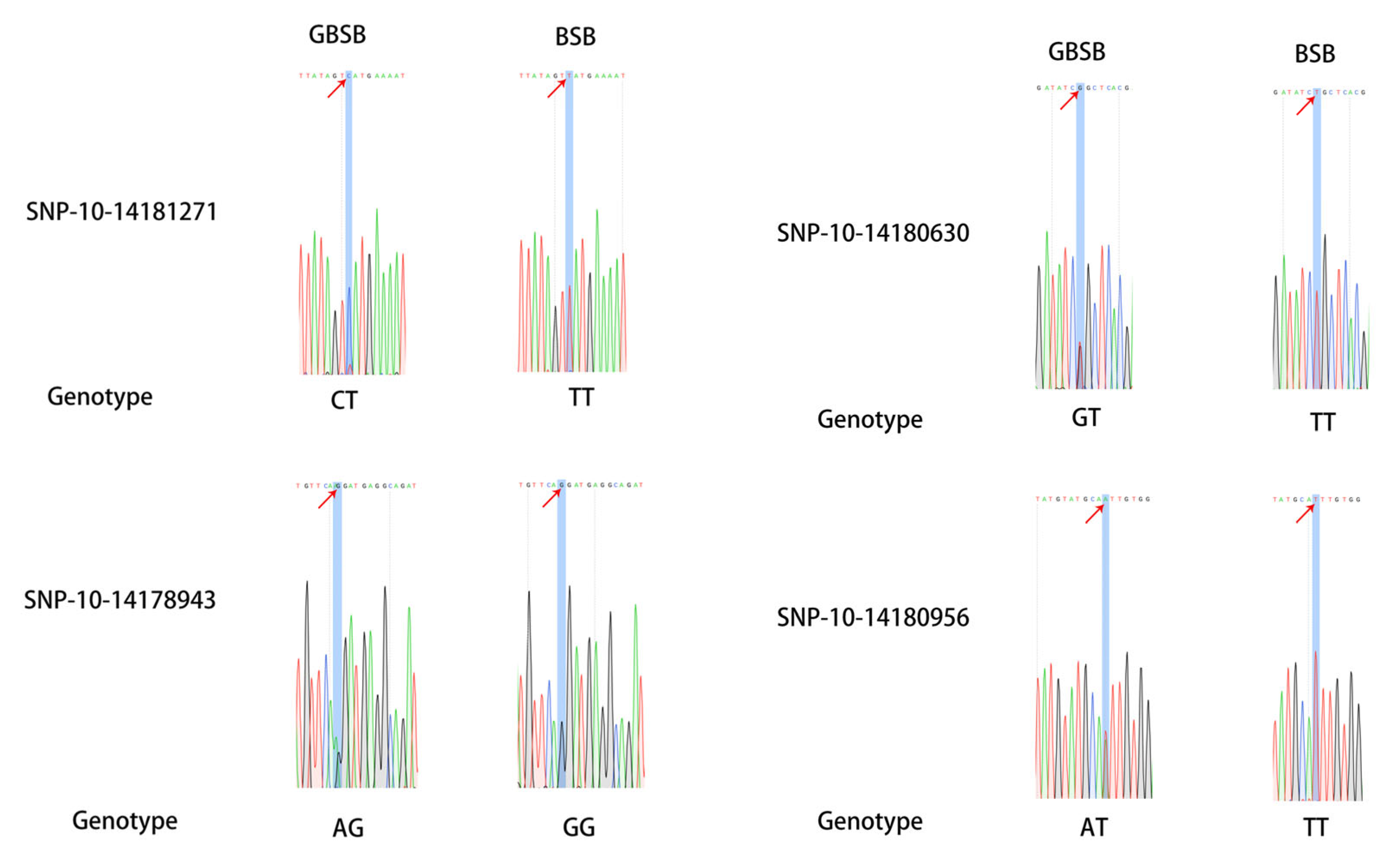

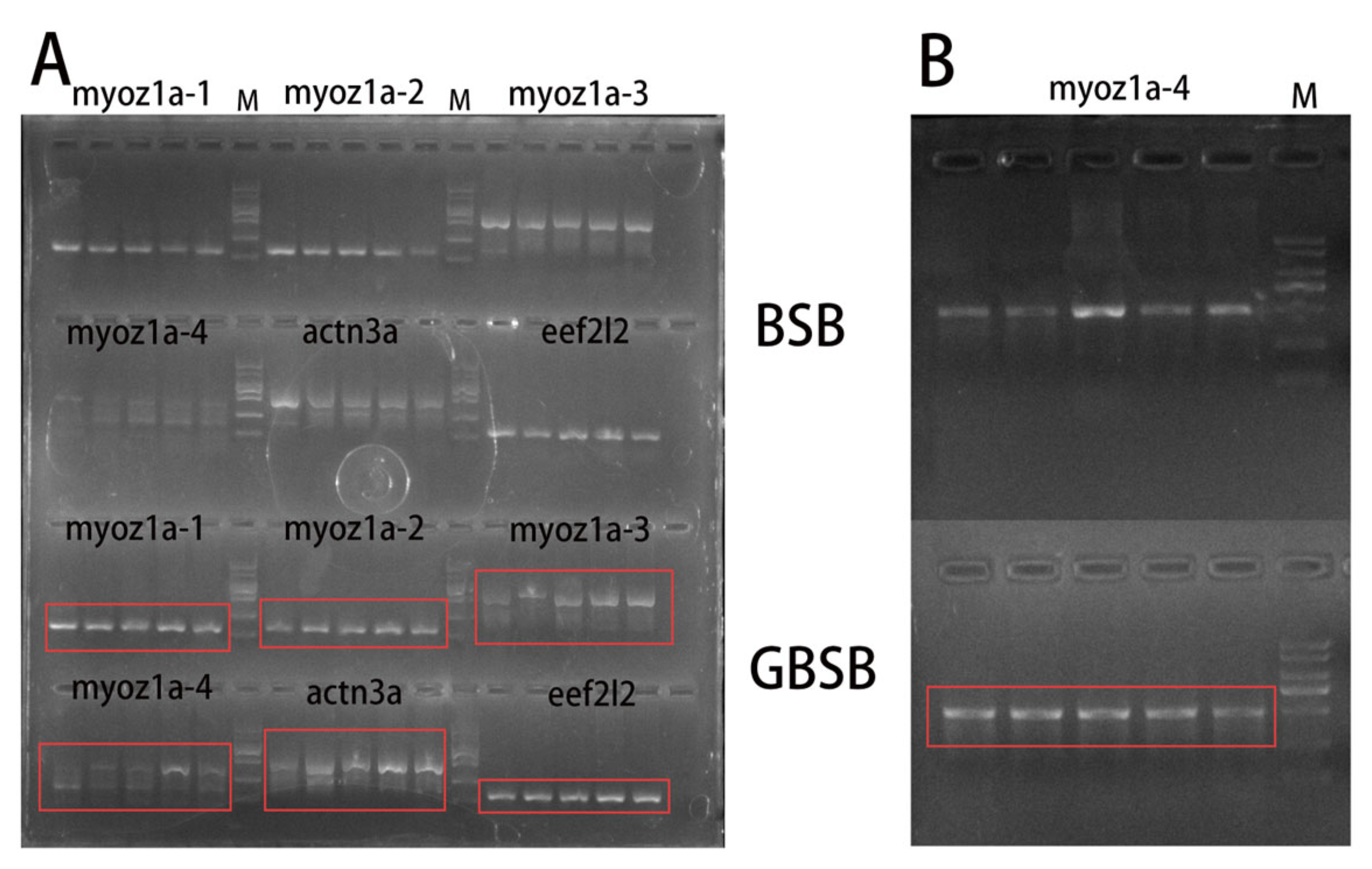

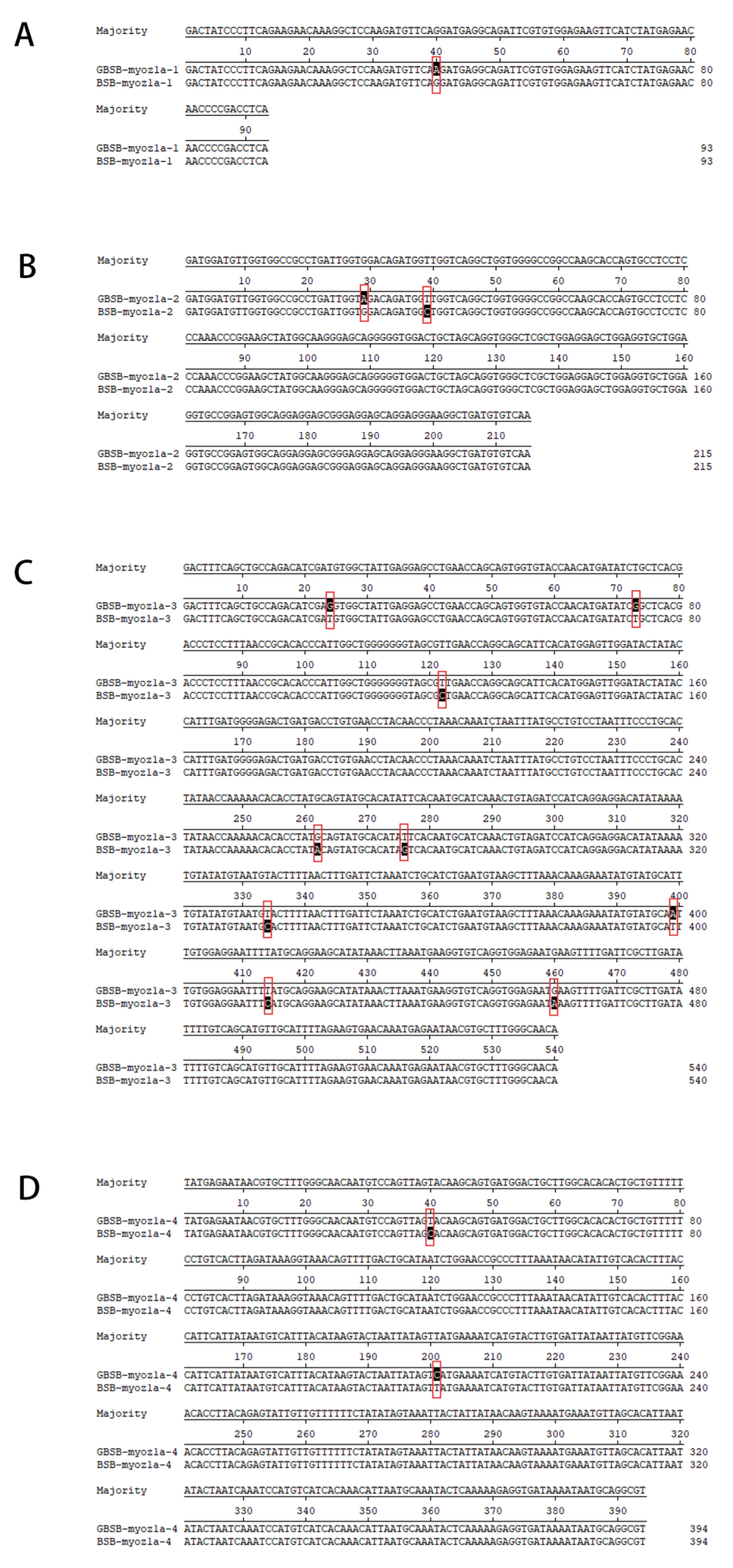

3.2. Validation and Analysis of Core SNP Sites

3.3. Functional Analysis of Core SNP Sites Sequences

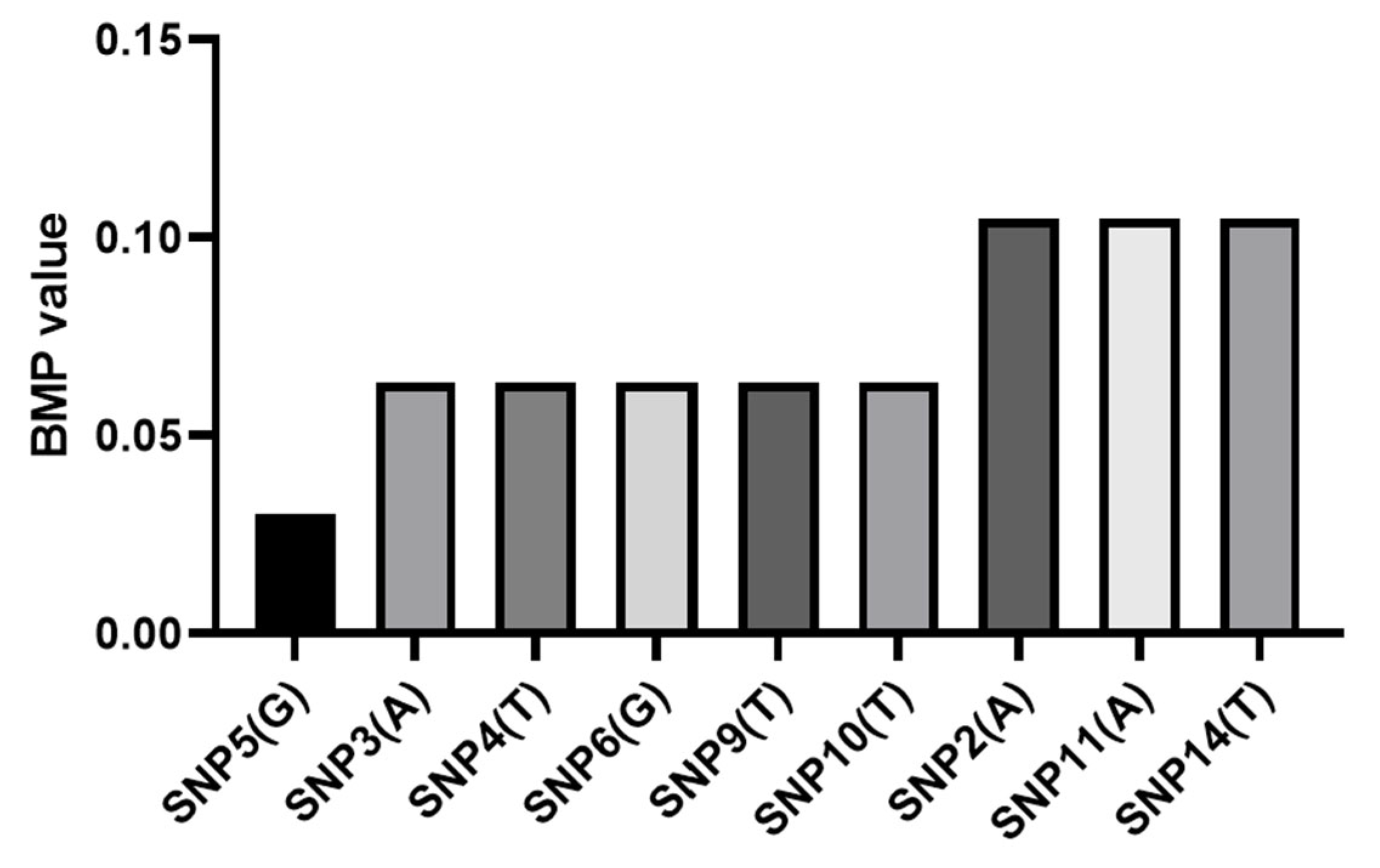

3.4. Analysis of Core SNP Sites Polymorphism

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Z.; Luo, W.; Liu, H.; Zeng, C.; Liu, X.; Yi, S.; Wang, W. Transcriptome analysis and SSR/SNP markers information of the blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, C.; Tao, M.; Qin, Q.; Zhang, C.; Luo, K.; Zhao, R.; Wang, J.; Ren, L.; Xiao, J.; et al. Establishment and application of distant hybridization technology in fish. Sci. China Life Sci. 2019, 62, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Zeng, Y.; Qin, Q.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Tao, M.; Zhang, C.; Tang, C.; Liu, S. Comparative analysis of the texture, composition, antioxidant capacity and nutrients of natural gynogenesis blunt snout bream and its parent muscle. Reprod. Breed. 2022, 2, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Z.; Liao, A.M.; Tao, M.; Qin, Q.B.; Luo, K.K.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, F.Z.; Wang, Y.D.; et al. Macro-Hybrid and Micro-Hybrid of Fish. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 18, e70106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, S.J.; Zhang, C.; Tao, M.; Peng, L.; You, C.; Xiao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, G.; Luo, K.; et al. Induced gynogenesis in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) using irradiated sperm of allotetraploid hybrids. Mar. Biotechnol. 2011, 13, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.D.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.J.; Tao, M.; Zeng, C.; Liu, Y. Induction of gynogenesis in Japanese crucian carp (Carassius cuvieri). Acta Genet. Sin. 2006, 33, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.H.; You, F.; Sun, W.; Yan, B.L.; Zhang, P.J.; Jing, B.X. Induction of diploid gynogenesis in turbot Scophthalmus maximus with left-eyed flounder Paralichthys olivaceus sperm. Aquac. Int. 2008, 16, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.D.; Tao, M.; Liu, S.J.; Zhang, C.; Duan, W.; Shen, J.M.; Wang, J.; Zeng, C.; Long, Y.; Liu, Y. Induction of gynogenesis in red crucian carp using spermatozoa of blunt snout bream. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2007, 17, 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, A.M.; Zhang, S.X.; Yu, Q.Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, H.; Wu, P.; Ding, Y.; Hu, B.; Liu, W.; Tao, M. Formation and characterization of artificial gynogenetic northern snakehead (Channa argus) induced by inactivated sperm of mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Aquaculture 2025, 595, 741488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Z.; Wang, S.; Tang, C.C.; Tao, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, Q.; Luo, K.; Wu, C.; Hu, F. The Research Advances in Distant Hybridization and Gynogenesis in Fish. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e12972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Luo, Y.X.; Geng, C.; Liao, A.; Zhao, R.; Tan, H.; Yao, J.; Wang, S.; Luo, K.; Qin, Q. Production of a diploid hybrid with fast growth performance derived from the distant hybridization of Hypophthalmichthys nobilis (female) Megalobrama amblycephala (male). Reprod. Breed. 2022, 2, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.W.; Fu, Y.Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Luo, K.; Zhang, C.; Tao, M.; Liu, S. Further evidence for paternal DNA transmission in gynogenetic grass carp. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Ji, W.W.; Zeng, Y.; Tang, J.; Wu, C.; Qin, Q.B.; Yi, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, R.R.; Tao, M.; et al. The analysis of growth performance and expression of growth-related genes in natural gynogenic blunt snout bream muscle derived from the blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala, ♀)× Chinese perch (Siniperca chuatsi, ♂). Aquaculture 2024, 590, 741052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignal, A.; Milan, D.; SanCristobal, M.; Eggen, A. A review on SNP and other types of molecular markers and their use in animal genetics. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2002, 34, 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinds, D.A.; Stuve, L.L.; Nilsen, G.B.; Halperin, E.; Eskin, E.; Ballinger, D.G.; Frazer, K.A.; Cox, D.R. Whole-genome patterns of common DNA variation in three human populations. Science 2005, 307, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helyar, S.J.; Hemmer-Hansen, J.; Bekkevold, D.; Taylor, M.I.; Ogden, R.; Limborg, M.T.; Cariani, A.; Maes, G.E.; Diopere, E.; Carvalho, G.R.; et al. Application of SNPs for population genetics of nonmodel organisms: New opportunities and challenges. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2011, 11, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenkrug, S.C.; Freking, B.A.; Smith, T.P.L.; Rohrer, G.A.; Keele, J.W. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) discovery in porcine expressed genes. Anim. Genet. 2002, 33, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haegeman, A.; Williams, J.L.; Law, A.; Van Zeveren, A.; Peelman, L.J. Mapping and SNP analysis of bovine candidate genes for meat and carcass quality. Anim. Genet. 2003, 34, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrini, R.; Nicoloso, L.; Crepaldi, P.; Milanesi, E.; Marino, R.; Perini, D.; Pariset, L.; Dunner, S.; Leveziel, H.; Williams, J.L.; et al. Traceability of four European protected geographic indication (PGI) beef products using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and Bayesian statistics. Meat Sci. 2008, 80, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, S.; Watanabe, T.; Ogino, A.; Shimizu, K.; Morita, M.; Sugimoto, Y.; Takasuga, A. Application of highly differentiated SNPs between Japanese Black and Holstein to a breed assignment test between Japanese Black and F1 (Japanese Black x Holstein) and Holstein. Anim. Sci. J. 2013, 84, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Yu, X.; Tong, J. Novel single nucleotide polymorphisms of the insulin-like growth factor-I gene and their associations with growth traits in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 22471–22482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Xue, J.; Hu, Y.; Gan, L.; Shi, Y.; Yang, H.; Wei, Y. CARP is a potential tumor suppressor in gastric carcinoma and a single-nucleotide polymorphism in CARP gene might increase the risk of gastric carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Yu, X.; Pang, M.; Liu, H.; Tong, J. Molecular characterization and expression of three preprosomatostatin genes and their association with growth in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 182, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, F.; Kitamura, Y.; Nakajima, R.; Takahashi, M.; Goto, H.; Washida, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sasazaki, S.; Mannen, H. Application of DNA markers for discrimination between Japanese and Australian Wagyu beef. Anim. Sci. J. 2018, 89, 257–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Fu, H.C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Huang, H.Z. Genome-wide association study reveals growth-related SNPs and candidate genes in mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Aquaculture 2022, 550, 737879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuktas, H.; Wang, S.; Li, P.; He, C.; Xu, P.; Sha, Z.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Baoprasertkul, P.; Somridhivej, B.; et al. Construction of genetic linkage maps and comparative genome analysis of catfish using gene-associated markers. Genetics 2009, 181, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, D.; Rubiolo, J.A.; Cabaleiro, S.; Martínez, P.; Bouza, C. Differential gene expression and SNP association between fast-and slow-growing turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.J.; Seiliez, I. Protein and amino acid nutrition and metabolism in fish: Current knowledge and future needs. Aquac. Res. 2010, 41, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A.N.M.; Rigaud, C.; Rokka, A.; Skaugen, M.; Lihavainen, J.H.; Vehniäinen, E.R. Changes in cardiac proteome and metabolome following exposure to the PAHs retene and fluoranthene and their mixture in developing rainbow trout alevins. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 830, 154846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, J.; Liao, A.; Tan, H.; Luo, Y.; Wu, P.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Qin, Q.; Tao, M.; et al. The formation of hybrid fish derived from hybridization of Megalobrama amblycephala (♀) × Siniperca chuatsi (♂). Aquaculture 2022, 548, 737547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePristo, M.A.; Banks, E.; Poplin, R.; Garimella, K.V.; Maguire, J.R.; Hartl, C.; Philippakis, A.A.; del Angel, G.; Rivas, M.A.; Hanna, M.; et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meaburn, E.; Butcher, L.M.; Liu, L.; Fernandes, C.; Hansen, V.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Plomin, R.; Craig, I.; Schalkwyk, L.C. Genotyping DNA pools on microarrays: Tackling the QTL problem of large samples and large numbers of SNPs. BMC Genom. 2005, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, C.Y.; Rong, C.Y.; Boyle, T. Popgene Microsoft Windows Based Freeware for Population Genetic Analysis; Molecular Biology and Biotechnology Centre, University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, M.C.; Barban, N.; Tropf, F.C. An Introduction to Statistical Genetic Data Analysis; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Botstein, D.; White, R.L.; Skolnick, M.; Davis, R.W. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1980, 32, 314. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, G.M. The genetic basis of developmental stability. I. Relationships between stability, heterozygosity and genomic coadaptation. Genetica 1993, 89, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.F.; Wang, Y.D.; Hu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, A.; Liu, W.; Chen, G.; Luo, K.; Tao, M.; Zhang, C. Analysis of the genetic characteristics and variations in disease-resistant grass carp based on whole-genome resequencing and transcriptome sequencing. Reprod. Breed. 2024, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrote, C.M.L.; Reiniger, L.R.S.; Silva, K.B.; Rabaiolli, S.M.D.S.; Stefanel, C.M. Determining the polymorphism information content of a molecular marker. Gene 2020, 726, 144175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Y.C.; Ma, D.M.; Bai, J.J.; Liu, H.; Li, S.J.; Liu, H.Y. SNPs identification in RNA-seq data of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) fed on formulated feed and association analysis with growth trait. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2016, 40, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga, Z.J.; Aslam, K.; Septiningsih, E.M.; Collard, B.C.Y. Evaluation of SSR and SNP markers for molecular breeding in rice. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2015, 3, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Qian, K.; Bao, F. Development of SNPs in Siniperca chuatsi Basilewsky using high-throughput sequencing. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2020, 12, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, J.S.; Liu, X.X.; Zhao, L.Y.; Yang, S.M. Identification of Yellow River Common Carp Based on SNP Markers. Chin. J. Fish. China. 2022, 35, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.Y.; Bai, J.J.; Fan, J.J.; Li, X.H.; Ye, X. SNPs detection in largemouth bass myostatin gene and its association with growth traits. J. Fish. China. 2010, 34, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.F.; Sun, H.L.; Dong, J.J.; Tian, Y.Y.; Hu, J.; Ye, X. Correlation analysis of mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi) growth hormone gene polymorphisms and growth traits. J. Genet. 2019, 98, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Lan, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, H. SNP identification in FBXO32 gene and their associations with growth traits in cattle. Gene 2013, 515, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, B.; Ye, M.; Xu, H.; Ma, E.; Ye, F.; Cui, C. Expression analysis, single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the Myoz1 gene and their association with carcase and meat quality traits in chickens. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 17, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wu, Y.; Bi, Y.; Bai, H.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, G.; Chang, G.; Wang, Z. MYOZ1 gene promotes muscle growth and development in meat ducks. Genes 2022, 13, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, K.; Li, X.Y.; Zhao, S.H.; Cao, J.H. Expression profiling of MYOZ1 Gene in Porcine Tissue and C2C12 cells. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2011, 10, 1917–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tomso, D.J.; Liu, X.; Bell, D.A. Single nucleotide polymorphism in transcriptional regulatory regions and expression of environmentally responsive genes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 207, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera, M.; álvarez-Dios, J.A.; Millán, A.; Pardo, B.G.; Bouza, C.; Hermida, M.; Fernández, C.; Herrán, R.D.L.; Molina-Luzón, M.J.; Martínez, P. Validation of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers from an immune Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) turbot, Scophthalmus maximus, database. Aquaculture 2011, 313, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.; Alvarez-Dios, J.A.; Fernandez, C.; Bouza, C.; Vilas, R.; Martinez, P. Development and validation of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) markers from two transcriptome 454-runs of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) using high-throughput genotyping. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 5694–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Average Re-Sequencing Depth | Number of Reads | Average Sequencing Bases/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSB1 | 6.54× | 47,904,234 | 95.83 |

| BSB2 | 6.25× | 45,894,576 | 95.81 |

| BSB3 | 6.34× | 46,494,812 | 96.58 |

| GBSB1 | 6.26× | 45,818,504 | 96.5 |

| GBSB2 | 6.31× | 46,168,860 | 96.79 |

| GBSB3 | 6.52× | 47,828,520 | 95.99 |

| SNP No. | Gene Symbol | Chromosome | Location | Mutation Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | actn3a | 18 | 15,442,468 | T/C |

| 2 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,178,943 | G/A |

| 3 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,179,308 | G/A |

| 4 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,179,318 | C/T |

| 5 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,180,581 | T/G |

| 6 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,180,630 | T/G |

| 7 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,180,679 | C/T |

| 8 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,180,819 | A/G |

| 9 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,180,833 | G/T |

| 10 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,180,891 | C/T |

| 11 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,180,956 | T/A |

| 12 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,180,971 | C/T |

| 13 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,181,017 | A/G |

| 14 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,181,110 | C/T |

| 15 | myoz1a | 10 | 14,181,271 | T/C |

| 16 | eef2l2 | 4 | 21,609,175 | G/C |

| SNP | Feature ID | Annotation | Length of Contig (bp) | ORF | Length of ORF (aa) | Amino Acid | SNP Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP-18-15442468 | XM_048167370.1 | actinin alpha 3a | 3240 | 204-2894 | 896 | Ser 885 Ser TCT → TCC | 2858 |

| SNP-10-14178943 | XM_048204714.1 | myozenin 1a | 1913 | 183-1148 | 321 | Arg 73 Lys AGG → AAG | 400 |

| SNP-10-14179308 | Gly 120 Arg GGA → AGA | 540 | |||||

| SNP-10-14179318 | Ala 123 Val GCT → GTT | 550 | |||||

| SNP-10-14180581 | Asp 267 Glu GAT → GAG | 983 | |||||

| SNP-10-14180630 | Cys 284 Gly TGC → GGC | 1032 | |||||

| SNP-10-14180679 | Ala 300 Val GCT → GTT | 1081 | |||||

| SNP-10-14180819 | 3′ UTR | 1221 | |||||

| SNP-10-14180833 | 1235 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180891 | 1293 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180956 | 1358 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180971 | 1373 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14181017 | 1419 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14181110 | 1512 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14181271 | 1673 | ||||||

| SNP-4-21609175 | XM_048188247.1 | Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2, like 2 | 3199 | 153-2738 | 861 | Ala 734 Ala GCC → GCG | 2354 |

| SNP | Allele | Genotype Frequency | PIC | Ne | H | MAF | Hardy–Weinberg Eguiliberum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSB | GBSB | GBSB (BSB) | ||||||

| SNP-18-15442468 | T | 0.8165 | - | 0 (0.2547) | 1.9348 | 0.4832 | 0.3333 | χ2 = 8.279 (p = 0.004) |

| C | 0.1835 | 1 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14178943 | G | 1 | 0.5774 | 0.3689 (0) | 1.5000 | 0.3333 | 0.1667 | χ2 = 3.215 (p = 0.073) |

| A | - | 0.4226 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14179308 | G | 1 | 0.7071 | 0.3284 (0) | 1.3333 | 0.2500 | 0.1250 | χ2 = 2.059 (p = 0.151) |

| A | - | 0.2929 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14179318 | C | 1 | 0.7071 | 0.3284 (0) | 1.3333 | 0.2500 | 0.1250 | χ2 = 2.059 (p = 0.151) |

| T | - | 0.2929 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180581 | T | 1 | 0.8165 | 0.2547 (0) | 1.2000 | 0.1667 | 0.0833 | χ2 = 1.212 (p = 0.271) |

| G | - | 0.1835 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180630 | T | 1 | 0.7071 | 0.3284 (0) | 1.3333 | 0.2500 | 0.1250 | χ2 = 2.059 (p = 0.151) |

| G | - | 0.2929 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180679 | C | 0.4082 | 0.7071 | 0.3284 (0.3664) | 1.9737 | 0.4933 | 0.3333 | χ2 = 1.086 (p = 0.297) |

| T | 0.5918 | 0.2929 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180819 | A | 0.9129 | 0.8165 | 0.2547 (0.1464) | 1.3055 | 0.2340 | 0.1250 | χ2 = 0.238 (p = 0.626) |

| G | 0.0871 | 0.1835 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180833 | G | 1 | 0.7071 | 0.3284 (0) | 1.3333 | 0.2500 | 0.1250 | χ2 = 2.059 (p = 0.151) |

| T | - | 0.2929 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180891 | C | 1 | 0.7071 | 0.3284 (0) | 1.3333 | 0.2500 | 0.1250 | χ2 = 2.059 (p = 0.151) |

| T | - | 0.2929 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180956 | T | 1 | 0.5774 | 0.3689 (0) | 1.5000 | 0.3333 | 0.1667 | χ2 = 3.215 (p = 0.073) |

| A | - | 0.4226 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14180971 | C | 0.8165 | 0.8165 | 0.2547 (0.2547) | 1.4279 | 0.2997 | 0.1667 | χ2 = 0 (p = 1) |

| T | 0.1835 | 0.1835 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14181017 | A | 0.5774 | 0.7071 | 0.3284 (0.3689) | 1.8503 | 0.4595 | 0.2917 | χ2 = 0.220 (p = 0.639) |

| G | 0.4226 | 0.2929 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14181110 | C | 1 | 0.5774 | 0.3689 (0) | 1.5000 | 0.3333 | 0.1667 | χ2 = 3.215 (p = 0.073) |

| T | - | 0.4226 | ||||||

| SNP-10-14181271 | T | 0.7071 | 0.7071 | 0.3284 (0.3284) | 1.7071 | 0.4142 | 0.2500 | χ2 = 0 (p = 1) |

| C | 0.2929 | 0.2929 | ||||||

| SNP-4-21609175 | G | 0.5774 | 0.8165 | 0.2547 (0.3689) | 1.7314 | 0.4224 | 0.2500 | χ2 = 0.812 (p = 0.367) |

| C | 0.4226 | 0.1835 | ||||||

| SNP | SNP5 | SNP3 | SNP4 | SNP6 | SNP9 | SNP10 | SNP2 | SNP11 | SNP14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP | 0.030 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.105 | 0.105 | 0.105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, P.; Wei, Y.; Weng, S.; Hu, M.; Li, J.; Tang, W.; Zhang, L.; Qin, Q.; Yi, T.; Li, W.; et al. Establishment and Polymorphism Analysis of SNP Markers in the Gynogenic Blunt Snout Bream. Biology 2026, 15, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020188

Wu P, Wei Y, Weng S, Hu M, Li J, Tang W, Zhang L, Qin Q, Yi T, Li W, et al. Establishment and Polymorphism Analysis of SNP Markers in the Gynogenic Blunt Snout Bream. Biology. 2026; 15(2):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020188

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Ping, Yuhuan Wei, Siyao Weng, Mingguang Hu, Jiaxing Li, Wenxuan Tang, Lei Zhang, Qinbo Qin, Ting Yi, Wuhui Li, and et al. 2026. "Establishment and Polymorphism Analysis of SNP Markers in the Gynogenic Blunt Snout Bream" Biology 15, no. 2: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020188

APA StyleWu, P., Wei, Y., Weng, S., Hu, M., Li, J., Tang, W., Zhang, L., Qin, Q., Yi, T., Li, W., Tao, M., Zhang, C., Liu, Q., & Liu, S. (2026). Establishment and Polymorphism Analysis of SNP Markers in the Gynogenic Blunt Snout Bream. Biology, 15(2), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020188