Chronic Heat Stress Induces Stage-Specific Molecular and Physiological Responses in Spotted Seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus): Focus on Thermosensory Signaling and HPI Axis Activation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish and Experimental Design

2.2. Acclimation and Rearing Conditions

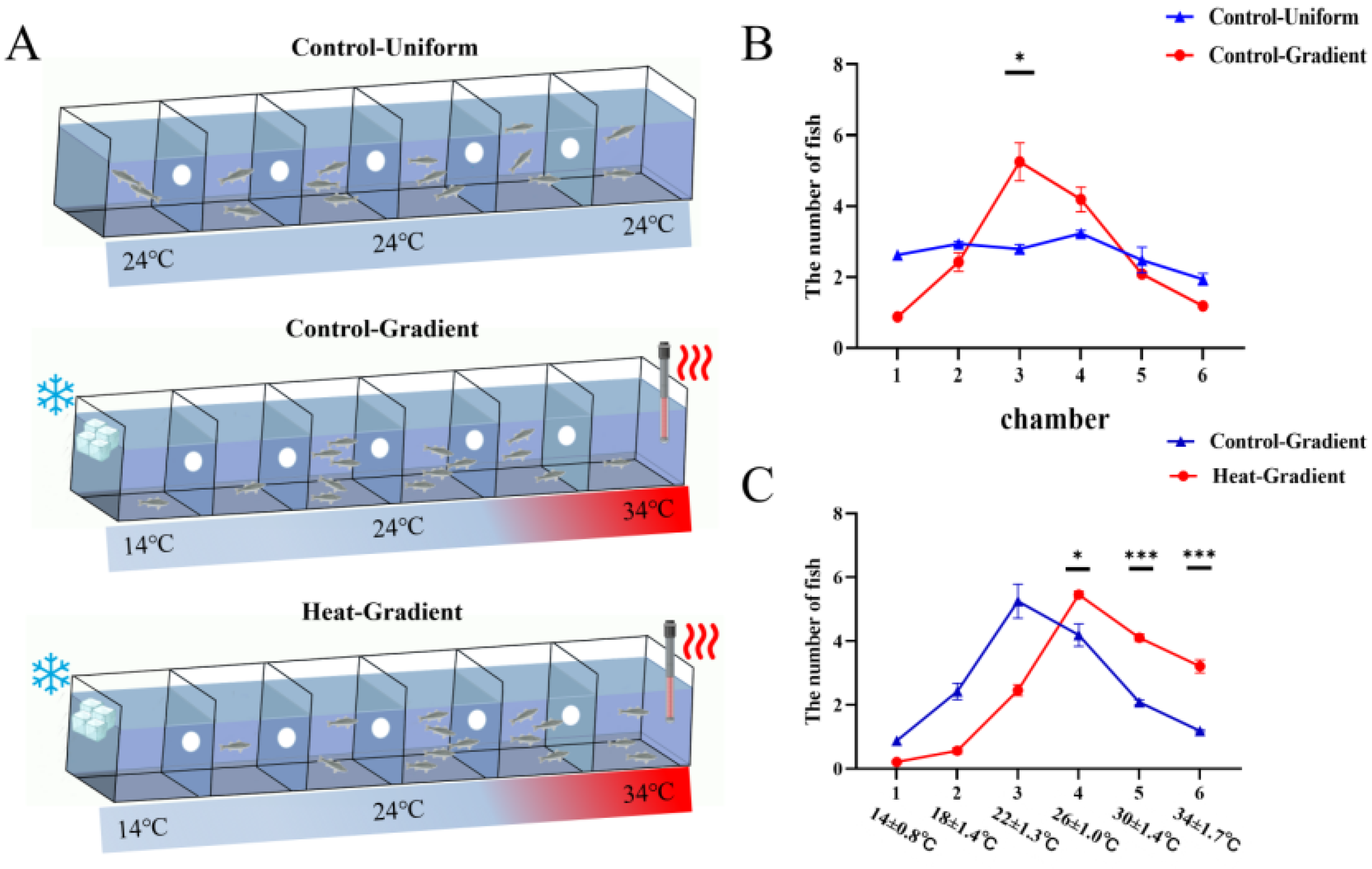

2.3. Behavioral Tests

2.4. Sample Collection

2.5. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

2.6. RNA Sequencing and Analysis

2.7. Serum Cortisol and Glucose Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Shift in Thermal Preference Following Acclimation in Late Larvae

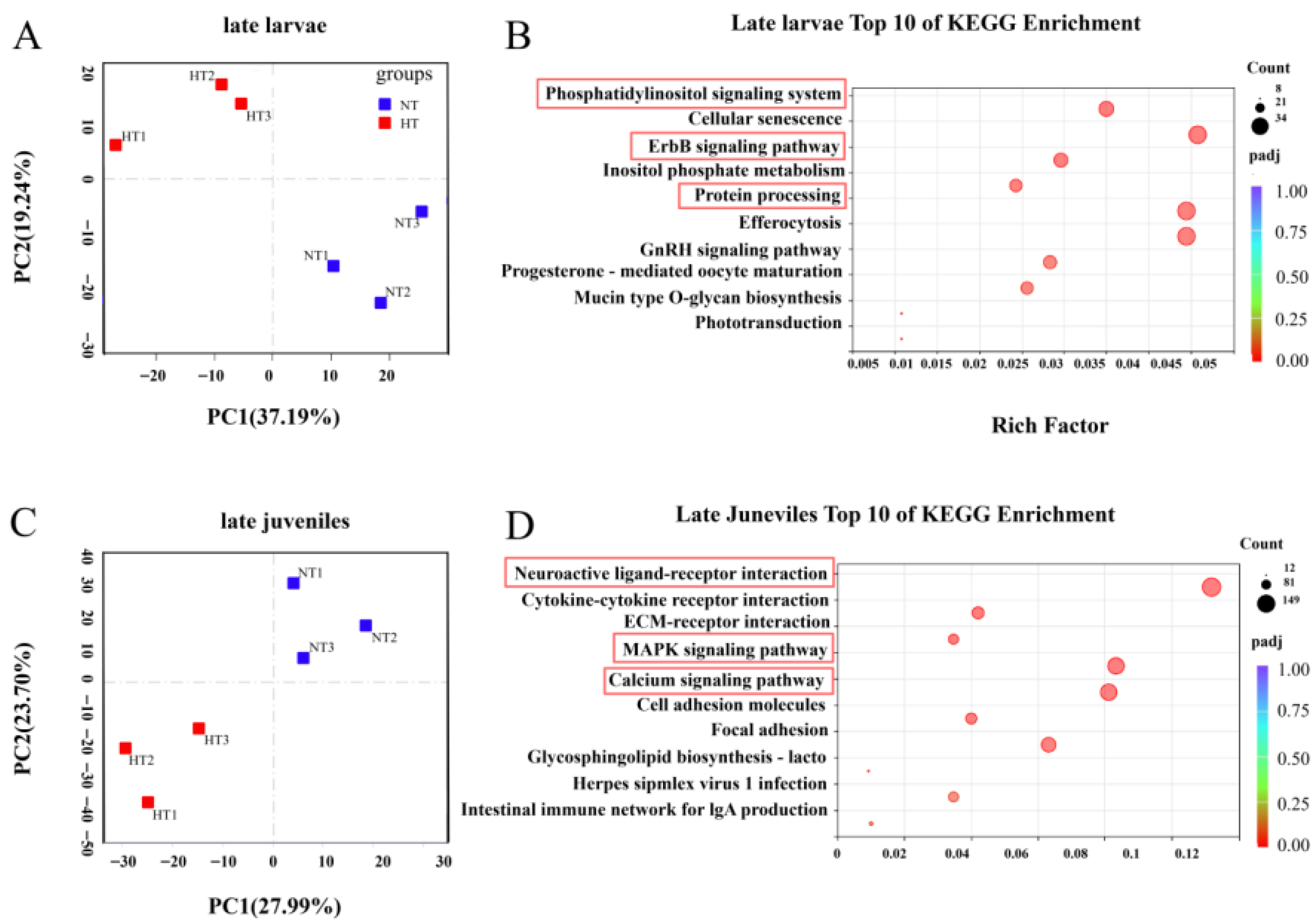

3.2. Distinct Transcriptomic Responses to Heat Stress in the Brain Across Developmental Stages

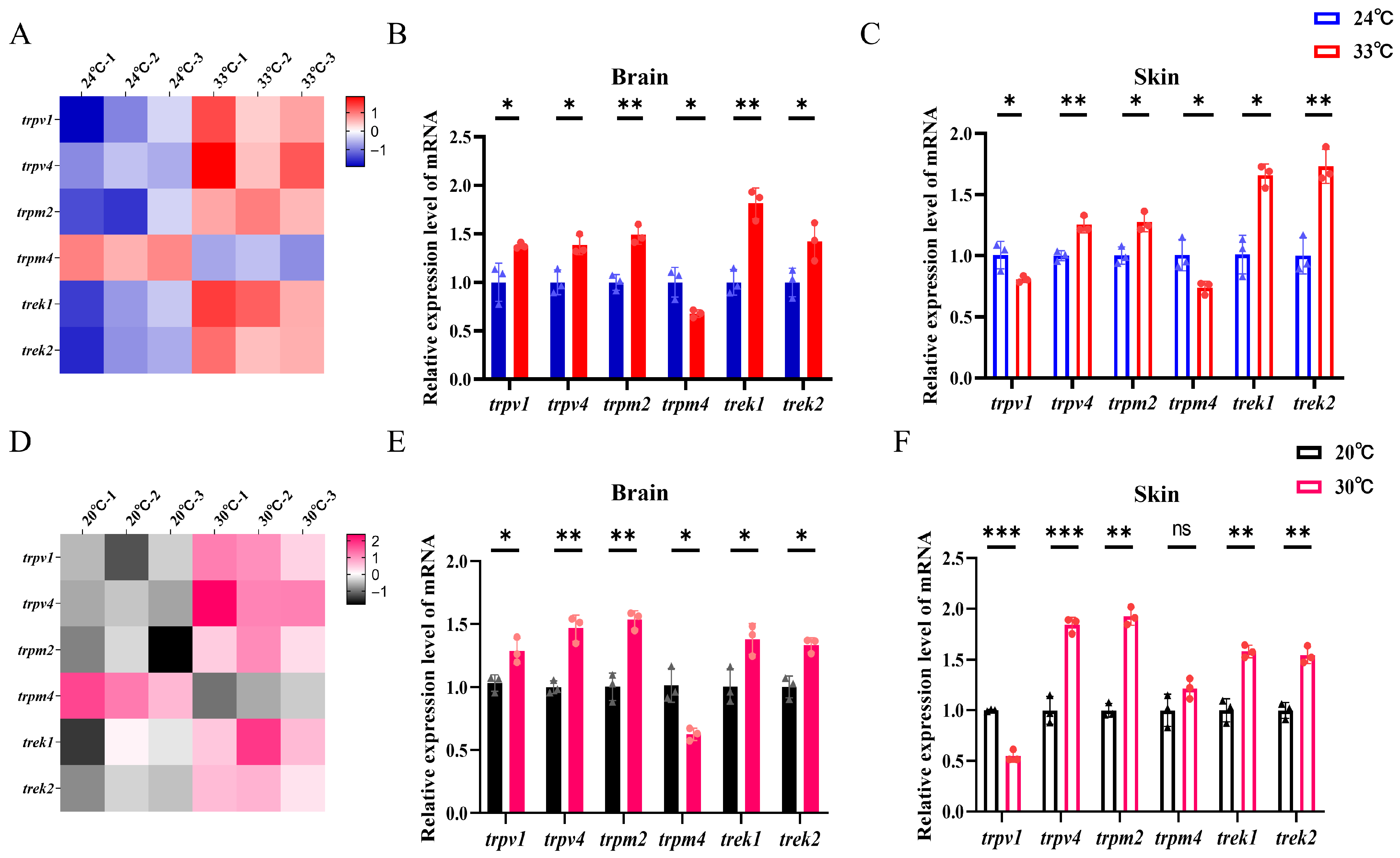

3.3. Expression of Genes Related to Temperature Sensing

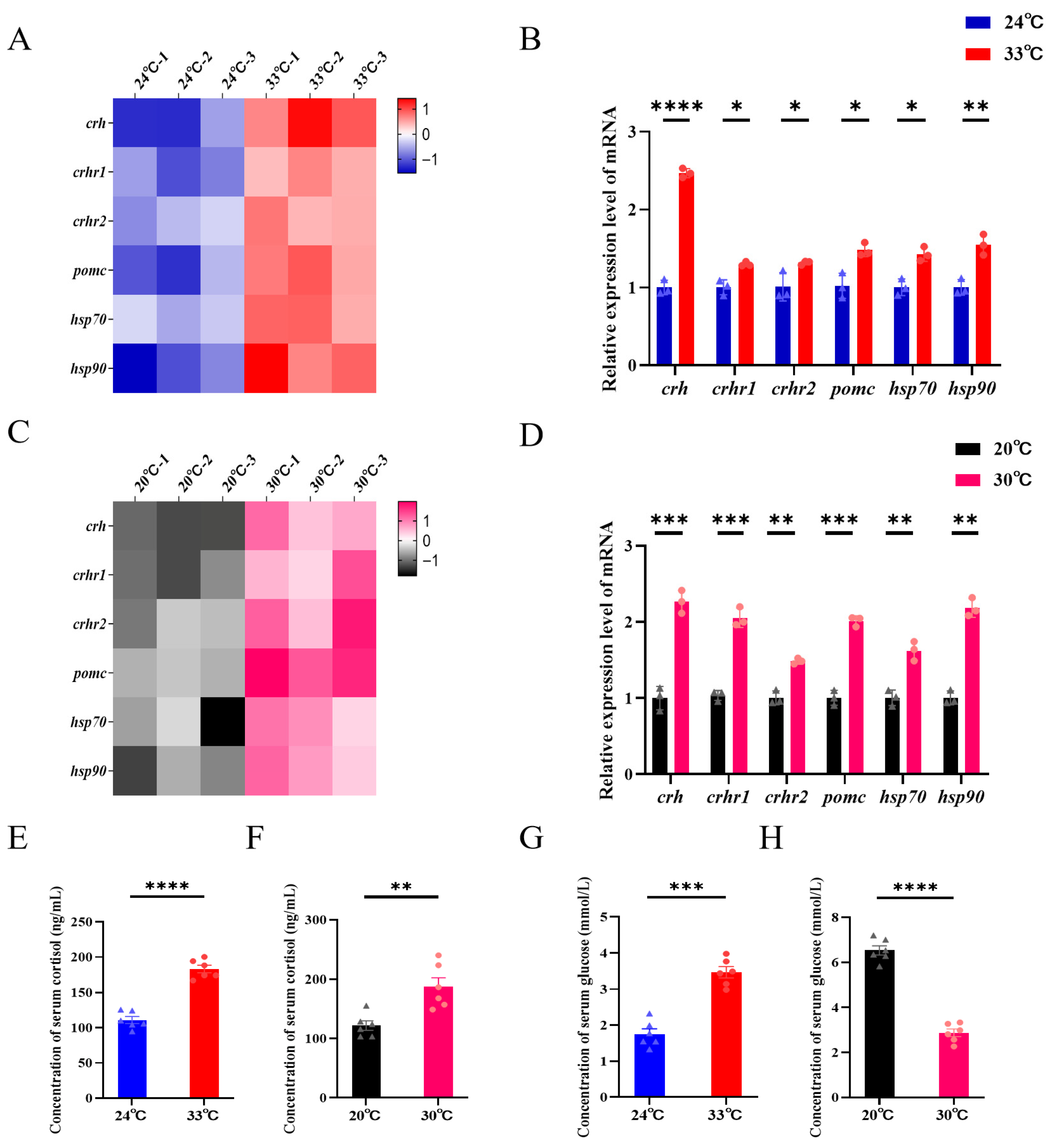

3.4. Stress Pathway Activation and Systemic Physiology Following Heat Stress

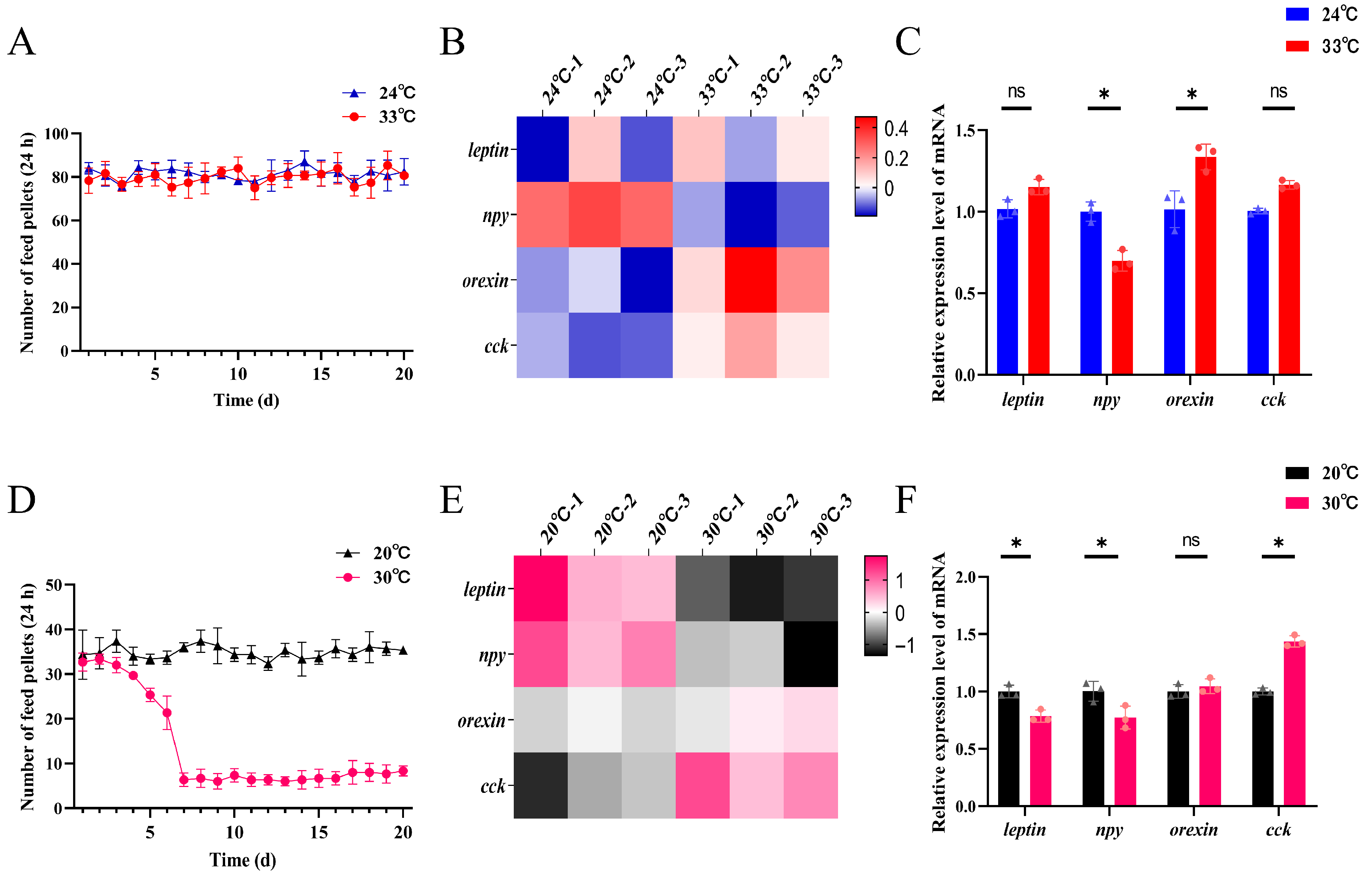

3.5. Analysis of Feeding Behavior and Brain Appetite-Regulating Gene Expression in Response to Heat Stress Across Developmental Stages

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dellagostin, E.N.; Martins, A.W.S.; Blödorn, E.B.; Silveira, T.L.R.; Komninou, E.R.; Varela Junior, A.S.; Corcini, C.D.; Nunes, L.S.; Remião, M.H.; Collares, G.L.; et al. Chronic Cold Exposure Modulates Genes Related to Feeding and Immune System in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 128, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-H.; Yang, F.-F.; Liao, S.-A.; Miao, Y.-T.; Ye, C.-X.; Wang, A.-L.; Tan, J.-W.; Chen, X.-Y. High Temperature Induces Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Pufferfish (Takifugu obscurus) Blood Cells. J. Therm. Biol. 2015, 53, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Abraham, J.; Trenberth, K.E.; Reagan, J.; Zhang, H.-M.; Storto, A.; Von Schuckmann, K.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Mann, M.E.; et al. Record High Temperatures in the Ocean in 2024. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 42, 1092–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, E.C.; Benthuysen, J.A.; Darmaraki, S.; Donat, M.G.; Hobday, A.J.; Holbrook, N.J.; Schlegel, R.W.; Gupta, A.S. Marine Heatwaves. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2021, 13, 313–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, A.L.; Low, P.J.; Ellis, J.R.; Reynolds, J.D. Climate Change and Distribution Shifts in Marine Fishes. Science 2005, 308, 1912–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, H.; Wei, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Z.; Ling, Q. Heat Stress Induces Pathological and Molecular Responses in the Gills of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) Revealed by Histology, Transcriptomics, and DNA Methylomics. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2025, 55, 101485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, J.L.; Mitchell, M.D.; Vaughan, G.O.; Ripley, D.M.; Shiels, H.A.; Burt, J.A. Impacts of Ocean Warming on Fish Size Reductions on the World’s Hottest Coral Reefs. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haesemeyer, M. Thermoregulation in Fish. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020, 518, 110986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, J.; Zhu, J.; Tang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Gu, W.; Jiang, H.; Wang, D.; Xu, S.; et al. Simulated Cold Spell: Changes of Lipid Metabolism on Silver Pomfret during Cooling and Rewarming. Aquaculture 2024, 590, 741033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C.M.; Thorson, J.T.; Pinsky, M.L.; Oken, K.L.; Wiedenmann, J.; Jensen, O.P. Impacts of Historical Warming on Marine Fisheries Production. Science 2019, 363, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Siemens, J. TRP Ion Channels in Thermosensation, Thermoregulation and Metabolism. Temperature 2015, 2, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Saito, C.T. Evolution of Temperature Receptors and Their Roles in Sensory Diversification and Adaptation. Zool. Sci. 2025, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Hughes, T.E.T.; Moiseenkova-Bell, V.Y. Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Channels. Subcell. Biochem. 2018, 87, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisembaum, L.G.; Loentgen, G.; L’Honoré, T.; Martin, P.; Paulin, C.-H.; Fuentès, M.; Escoubeyrou, K.; Delgado, M.J.; Besseau, L.; Falcón, J. Transient Receptor Potential-Vanilloid (TRPV1-TRPV4) Channels in the Atlantic Salmon, Salmo Salar. A Focus on the Pineal Gland and Melatonin Production. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 784416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, C.; Viana, F. Molecular and Cellular Limits to Somatosensory Specificity. Mol. Pain 2008, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Winkler, P.A.; Sun, W.; Lü, W.; Du, J. Architecture of the TRPM2 Channel and Its Activation Mechanism by ADP-Ribose and Calcium. Nature 2018, 562, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.M.; Zakon, H.H. Evolution of Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Ion Channels in Antarctic Fishes (Cryonotothenioidea) and Identification of Putative Thermosensors. Genome Biol. Evol. 2022, 14, evac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uray, I.P.; Uray, K. Mechanotransduction at the Plasma Membrane-Cytoskeleton Interface. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, Q.; Hor, C.C.; Pan, T.; Fatima, M.; Dong, X.; Duan, B.; Xu, X.Z.S. The Kainate Receptor GluK2 Mediates Cold Sensing in Mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Ferreras, A.M.; Barquín, J.; Blyth, P.S.A.; Hawksley, J.; Kinsella, H.; Lauridsen, R.; Morris, O.F.; Peñas, F.J.; Thomas, G.E.; Woodward, G.; et al. Chronic Exposure to Environmental Temperature Attenuates the Thermal Sensitivity of Salmonids. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Wang, H.; Kamm, G.B.; Pohle, J.; Reis, F.D.C.; Heppenstall, P.; Wende, H.; Siemens, J. The TRPM2 Channel Is a Hypothalamic Heat Sensor That Limits Fever and Can Drive Hypothermia. Science 2016, 353, 1393–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.B.; Preil, J.; Renner, U.; Zimmermann, S.; Kresse, A.E.; Stalla, G.K.; Keck, M.E.; Holsboer, F.; Wurst, W. Expression of CRHR1 and CRHR2 in Mouse Pituitary and Adrenal Gland: Implications for HPA System Regulation. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 4150–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, R.; Van Der Gaag, R.; Martens, G.; Wendelaar Bonga, S.; Flik, G. Differential Expression of Two Pro-Opiomelanocortin mRNAs during Temperature Stress in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). J. Endocrinol. 1998, 159, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, S.; Houdelet, C.; Bessa, E.; Geffroy, B.; Sadoul, B. Water Temperature Explains Part of the Variation in Basal Plasma Cortisol Level within and between Fish Species. J. Fish Biol. 2023, 103, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Pellegrin, L.; Nitz, L.F.; Da Costa, S.T.; Monserrat, J.M.; Garcia, L. Haematological and Oxidative Stress Responses in Piaractus Mesopotamicus under Temperature Variations in Water. Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 3017–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Li, T.; Kong, L.; Bi, B.; Hu, Q. Effects of Chronic Thermal Stress on the Physiology, Metabolism, Histology, and Gut Microbiota of Juvenile Schizothorax Grahami. Animals 2025, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Sun, G.; Meng, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Ma, R. Stress Response and Adaptation Mechanism of Triploid Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss) Treated with Chronic Heat Challenge. Aquaculture 2024, 593, 741282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, N.; Todgham, A.E.; Ackerman, P.A.; Bibeau, M.R.; Nakano, K.; Schulte, P.M.; Iwama, G.K. Heat Shock Protein Genes and Their Functional Significance in Fish. Gene 2002, 295, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, K.; Nie, H.; Yan, X. Revealing the Potential Regulatory Relationship between HSP70, HSP90 and HSF Genes under Temperature Stress. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2023, 134, 108607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksala, N.K.J.; Ekmekçi, F.G.; Ozsoy, E.; Kirankaya, S.; Kokkola, T.; Emecen, G.; Lappalainen, J.; Kaarniranta, K.; Atalay, M. Natural Thermal Adaptation Increases Heat Shock Protein Levels and Decreases Oxidative Stress. Redox Biol. 2014, 3, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kregel, K.C. Invited Review: Heat Shock Proteins: Modifying Factors in Physiological Stress Responses and Acquired Thermotolerance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 92, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustosa do Carmo, T.L.; Moraes de Lima, M.C.; de Vasconcelos Lima, J.L.; Silva de Souza, S.; Val, A.L. Tissue Distribution of Appetite Regulation Genes and Their Expression in the Amazon Fish Colossoma Macropomum Exposed to Climate Change Scenario. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, L.; Song, K.; Lu, K.; Zhang, L.; Ma, X.; Zhang, C. Effects of Dietary Vitamin E Levels on Growth, Antioxidant Capacity and Immune Response of Spotted Seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus) Reared at Different Water Temperatures. Aquaculture 2023, 565, 739141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. A Global Assessment of Coastal Marine Heatwaves and Their Relation With Coastal Urban Thermal Changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL093260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wen, C. Spatial Benefit Assessment and Marine Climate Response of Coastal Zone in Fujian Province under Cross-System Influence. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Lu, K.; Li, X.; Song, K.; Zhang, C. High Temperature Induces Oxidative Stress in Spotted Seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus) and Leads to Inflammation and Apoptosis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 154, 109913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wen, H.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Morphological and Molecular Responses of Lateolabrax maculatus Skeletal Muscle Cells to Different Temperatures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yan, L.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Qiu, L. Effects of Temperature and Salinity on Ovarian Development and Differences in Energy Metabolism Between Reproduction and Growth During Ovarian Development in the Lateolabrax maculatus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlke, F.T.; Wohlrab, S.; Butzin, M.; Pörtner, H.-O. Thermal Bottlenecks in the Life Cycle Define Climate Vulnerability of Fish. Science 2020, 369, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyano, M.; Candebat, C.; Ruhbaum, Y.; Álvarez-Fernández, S.; Claireaux, G.; Zambonino-Infante, J.-L.; Peck, M.A. Effects of Warming Rate, Acclimation Temperature and Ontogeny on the Critical Thermal Maximum of Temperate Marine Fish Larvae. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goikoetxea, A.; Sadoul, B.; Blondeau-Bidet, E.; Aerts, J.; Blanc, M.-O.; Parrinello, H.; Barrachina, C.; Pratlong, M.; Geffroy, B. Genetic Pathways Underpinning Hormonal Stress Responses in Fish Exposed to Short- and Long-Term Warm Ocean Temperatures. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 120, 106937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsop, D.; Vijayan, M.M. Molecular Programming of the Corticosteroid Stress Axis during Zebrafish Development. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2009, 153, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, N.J.; Peter, R.E. The Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Interrenal Axis and the Control of Food Intake in Teleost Fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001, 129, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lin, C.; Zhang, B.; Yan, L.; Zhang, B.; Wang, P.; Qiu, L.; Zhao, C. Identification of Scavenger Receptor (LmSRA3) Gene and Its Immune Response to Aeromonas Veronii in Lateolabrax maculatus. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2025, 164, 105320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Qin, F. The Xenopus Tropicalis Orthologue of TRPV3 Is Heat Sensitive. J. Gen. Physiol. 2015, 146, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gau, P.; Poon, J.; Ufret-Vincenty, C.; Snelson, C.D.; Gordon, S.E.; Raible, D.W.; Dhaka, A. The Zebrafish Ortholog of TRPV1 Is Required for Heat-Induced Locomotion. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 5249–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, Y.K. Molecular Characterization of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) Gene Transcript Variant mRNA of Chum Salmon Oncorhynchus Keta in Response to Salinity or Temperature Changes. Gene 2021, 795, 145779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.-H.; McNaughton, P.A. The TRPM2 Ion Channel Is Required for Sensitivity to Warmth. Nature 2016, 536, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyedi, P.; Czirják, G. Molecular Background of Leak K+ Currents: Two-Pore Domain Potassium Channels. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 559–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolicato, M.; Riegelhaupt, P.M.; Arrigoni, C.; Clark, K.A.; Minor, D.L. Transmembrane Helix Straightening and Buckling Underlies Activation of Mechanosensitive and Thermosensitive K(2P) Channels. Neuron 2014, 84, 1198–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Tominaga, M. TRPV3 in Skin Thermosensation and Temperature Responses. J. Physiol. Sci. 2025, 75, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, L.; Kamau, P.M.; Zheng, J.; Yang, F.; Yang, S.; Lai, R. Molecular Basis for Heat Desensitization of TRPV1 Ion Channels. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Ghosh, A.; Tiwari, N.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Goswami, C. Preferential Selection of Arginine at the Lipid-Water-Interface of TRPV1 during Vertebrate Evolution Correlates with Its Snorkeling Behaviour and Cholesterol Interaction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizalar, F.S.; Lucht, M.T.; Petzoldt, A.; Kong, S.; Sun, J.; Vines, J.H.; Telugu, N.S.; Diecke, S.; Kaas, T.; Bullmann, T.; et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3,5-Bisphosphate Facilitates Axonal Vesicle Transport and Presynapse Assembly. Science 2023, 382, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, G.; De Camilli, P. Phosphoinositides in Cell Regulation and Membrane Dynamics. Nature 2006, 443, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lush, M.E.; Piotrowski, T. ErbB Expressing Schwann Cells Control Lateral Line Progenitor Cells via Non-Cell-Autonomous Regulation of Wnt/β-Catenin. eLife 2014, 3, e01832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Ayelhan, H.; Sawut, R.; Chun-ming, S.H.I.; Ren-ming, Z. Analysis of High Temperature Tolerance in Early Development of Esox Lucius. Biotechnol. Bull. 2021, 37, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.F.; Nakamura, K. Central Neural Pathways for Thermoregulation. Front. Biosci. 2011, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Zhu, Y.; Li, L.; Gu, Z.; Wang, J.; Yuan, J. Kaempferol Attenuated Largemouth Bass Virus Caused Inflammation via Inhibiting NF-κB and ERK-MAPK Signaling Pathways. Aquaculture 2025, 607, 742626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Choo, H.J.; Ma, S.-X. Infrared Heat Treatment Reduces Food Intake and Modifies Expressions of TRPV3-POMC in the Dorsal Medulla of Obesity Prone Rats. Int. J. Hyperth. 2011, 27, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igual Gil, C.; Coull, B.M.; Jonas, W.; Lippert, R.N.; Klaus, S.; Ost, M. Mitochondrial Stress-Induced GFRAL Signaling Controls Diurnal Food Intake and Anxiety-like Behavior. Life Sci. Alliance 2022, 5, e202201495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolova, I.M. Energy-Limited Tolerance to Stress as a Conceptual Framework to Integrate the Effects of Multiple Stressors. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2013, 53, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, C.; Villegas-Ríos, D.; Moland, E.; Olsen, E.M. Sea Temperature Effects on Depth Use and Habitat Selection in a Marine Fish Community. J. Anim. Ecol. 2021, 90, 1787–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer. | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| trpm2 | CGCCTGGTCCAAACTGATCT | AACAGCACGTAGGCAAACAG |

| trpm4 | ACCCGTCACCGCATTTTTAG | TGCAACGCCGTCTGACCTTTG |

| trpv1 | CGTCGTCCTTGACATCGCTGAG | GCGATCTCTCCTCAAGCCTC |

| trpv4 | GGGTGGATGAGGTGAACTGG | GTCTCCGAAGCCGATTGTGGTG |

| trek1 | CCTGCCAGCCGTCATCTTCAAG | CCTTGCGTACTGTGACAGGT |

| trek2 | GACGGGCGAGTGTATGCATA | TCATTTCCCGAAGAGCTCCATC |

| crh | ATGAAGCTCAATTTACTTGGCACC | TAGTGGAGGGGCAGGTAGTC |

| crhr1 | TCTGAGGAGCAGCCAGAGAT | AGCTCGGGGACTTAAACTGC |

| crhr2 | TACTCAGGGCAGGGTCTCTC | AAGAGAGAGGGGAGGCAGAG |

| pomc | GAGTGTATCCGGCTCTGTCG | TCTTTAGTCGCCTGTCGCTG |

| hsp70 | GACGGAGGGAAGCCCAAAAT | TGGTTTTCCTTCATGCGGGT |

| hsp90 | TGGGCATCCATGAGGACTCTT | TCAGCAAGTCTCAAGATGATCC |

| leptin | ATGGACTACACTCTGGCCATC | GGATATCTTCGTGGCGGTACTCTC |

| npy | ATCATGGCGTTCACCTGGACTG | CGGCCTTTCAGACCCTCTTT |

| orexin | TGCTTCGCAAAGTGCTCAAC | GCTGAGGAGGATGCAGACTC |

| cck | CCGAAATCCATCCACCCCAA | TTGGCTTTGGGGTTCAGG |

| β-actin | CAACTGGGATGACATGGAGAAG | AACAGCACGTAGGCAAACAG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, G.; Niu, H.; Tang, X.; Wang, K.; Xia, X.; Fang, X.; Wang, X. Chronic Heat Stress Induces Stage-Specific Molecular and Physiological Responses in Spotted Seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus): Focus on Thermosensory Signaling and HPI Axis Activation. Biology 2026, 15, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020113

Zhang G, Niu H, Tang X, Wang K, Xia X, Fang X, Wang X. Chronic Heat Stress Induces Stage-Specific Molecular and Physiological Responses in Spotted Seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus): Focus on Thermosensory Signaling and HPI Axis Activation. Biology. 2026; 15(2):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020113

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Guozhu, Hao Niu, Xiangkai Tang, Kaile Wang, Xue Xia, Xiu Fang, and Xiaojie Wang. 2026. "Chronic Heat Stress Induces Stage-Specific Molecular and Physiological Responses in Spotted Seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus): Focus on Thermosensory Signaling and HPI Axis Activation" Biology 15, no. 2: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020113

APA StyleZhang, G., Niu, H., Tang, X., Wang, K., Xia, X., Fang, X., & Wang, X. (2026). Chronic Heat Stress Induces Stage-Specific Molecular and Physiological Responses in Spotted Seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus): Focus on Thermosensory Signaling and HPI Axis Activation. Biology, 15(2), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15020113