The Multifunctional Role of Patatin in Potato Tuber Sink Strength, Starch Biosynthesis, and Stress Adaptation: A Systematic Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Tuber as a Carbon Sink

1.2. Patatin: A Brief Historical and Functional Overview

1.3. Scope, Structure and Methodology of the Review

1.4. Search Results, Biasness Study Selection, and Characteristics of Included and Excluded Studies

1.5. Risk of Bias, Synthesis Outcomes, and Certainty of Evidence

2. Patatin Gene Family, Protein Architecture, and Cellular Trafficking

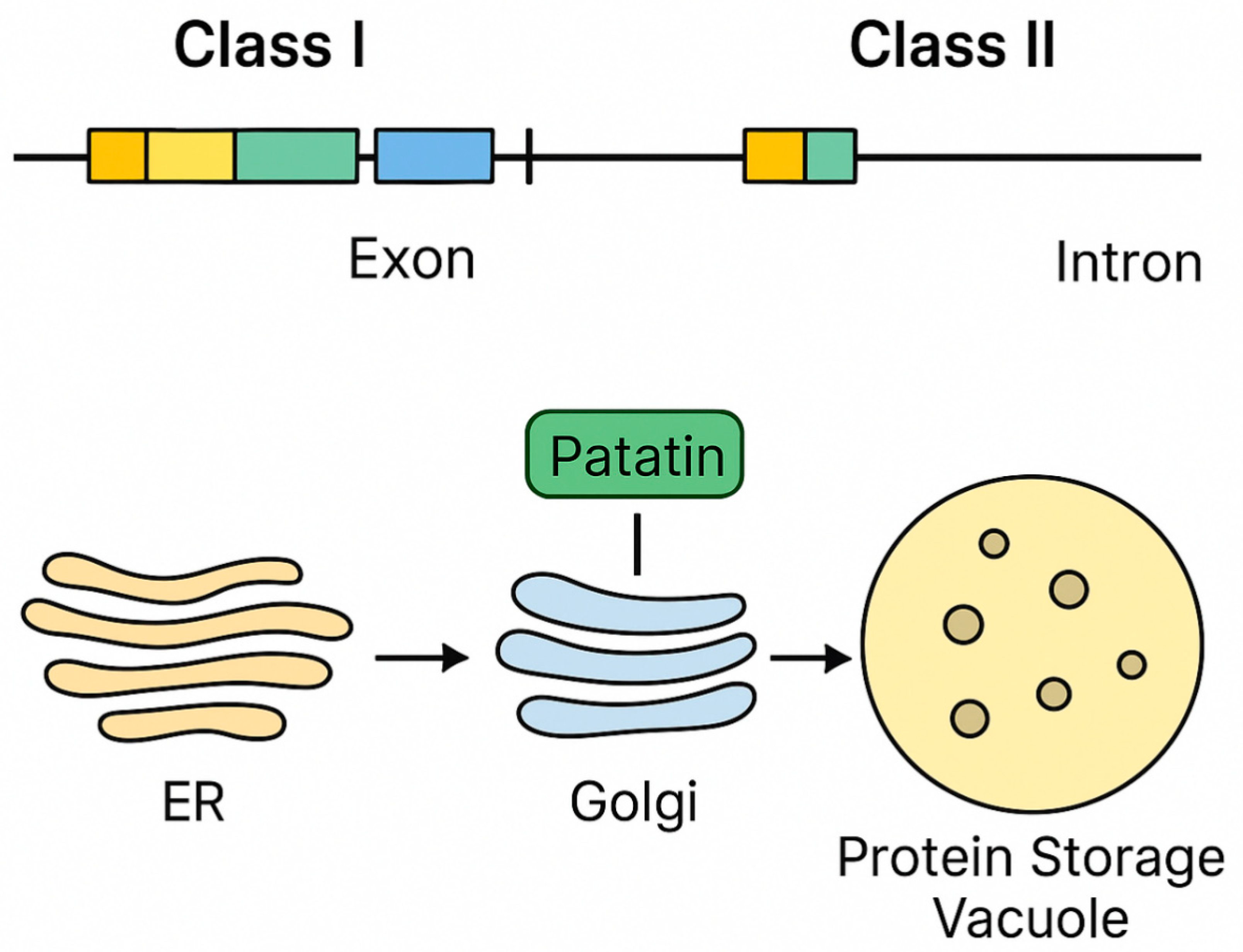

2.1. Gene Family Organization

2.2. Protein Biochemistry and Post-Translational Features

2.3. Cellular Localization and Turnover

| Patatin Gene/Isoform | Class | Promoter Features | Protein Size/Domain Features | Localization | Notes/Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| StPat I (e.g., PGSC0003DMG 400012345) | Class I | Strong tuber-specific promoter; sucrose-responsive elements (SURE); ABA-responsive motifs (ABRE) [14] | ~43 kDa; conserved patatin domain with Gly-X-Ser-X-Gly catalytic motif [23] | Vacuole (PSVs) [18] | Highly expressed in tubers; widely used in transgenic studies for tuber-specific expression [14] |

| StPat II (e.g., PGSC0003DM G400045678) | Class II | Weaker promoter activity; less tuber-specific; inducible by stress (ABA, drought) [31] | ~40–42 kDa; PLA2-like domain [32] | Vacuole; partial cytoplasmic aggregates [33] | Stress-associated isoform; contributes to lipid acyl hydrolase activity under abiotic stress [32] |

| StPat Class I promoter (synthetic constructs) | Class I | Contains SURE, ABRE, and TATA-like elements; high specificity to tuber parenchyma [14] | Used in gene constructs rather than direct protein product | Drives tuber-specific recombinant expression [18] | Widely used in potato biotechnology and heterologous protein expression [14] |

| StPat II isoform variants | Class II | Promoter enriched in ABA/ethylene-responsive motifs; low sucrose response [31] | ~41 kDa; isoforms with post-translational glycosylation variability [32] | Vacuole and transient ER retention [33] | Suggested role in stress adaptation and remobilization during sprouting [32] |

| Chimeric Patatin Promoters (e.g., B33) | Derived from Class I | Engineered for high tuber expression; retains SURE and ABRE motifs [14,18] | Not a protein product (promoter only) | N/A | Extensively used in metabolic engineering of potato tubers [18] |

3. Spatiotemporal Regulation of Patatin During Tuber Development

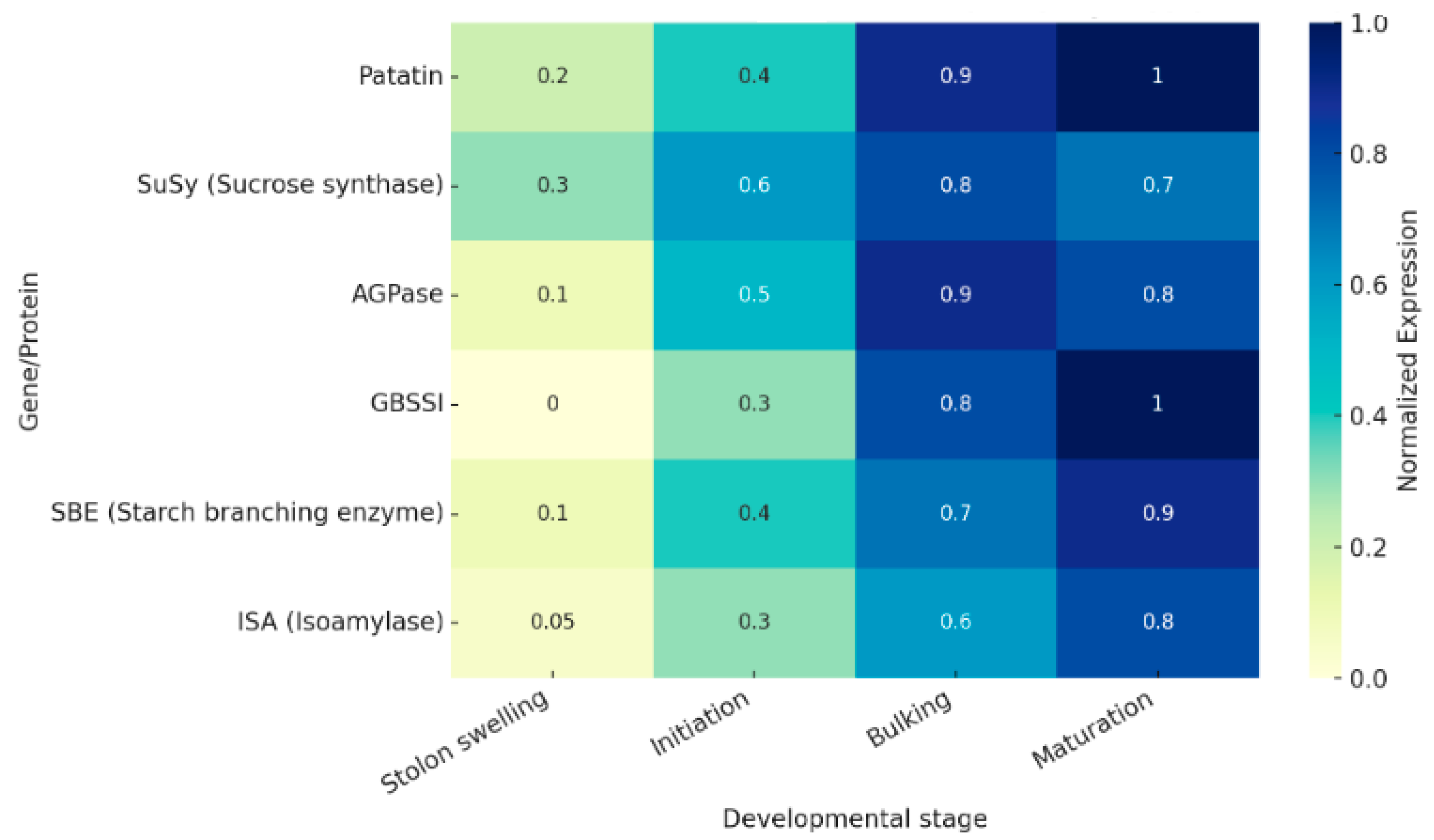

3.1. Developmental Timeline

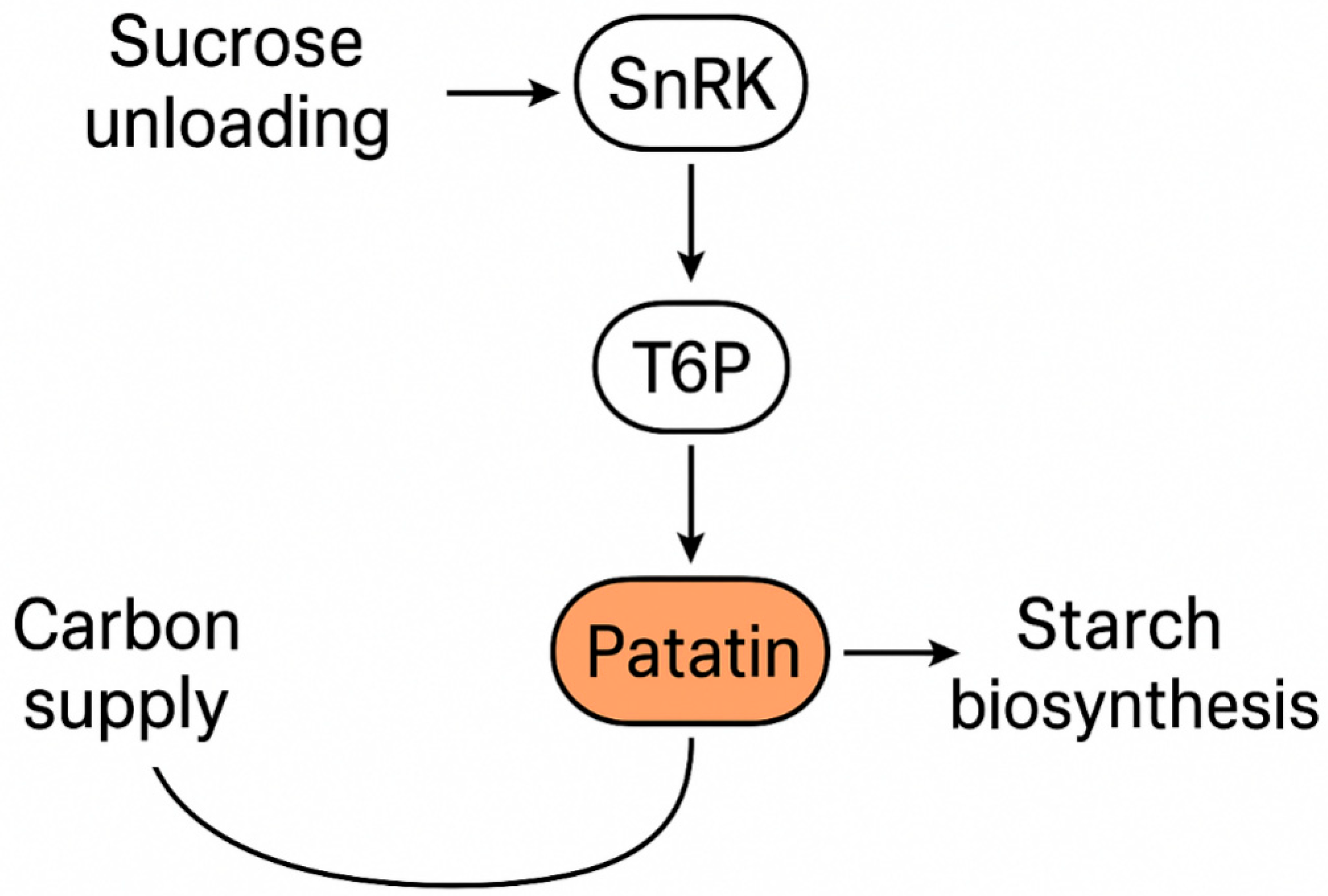

3.2. Regulatory Inputs

3.3. Co-Expression and Network Context

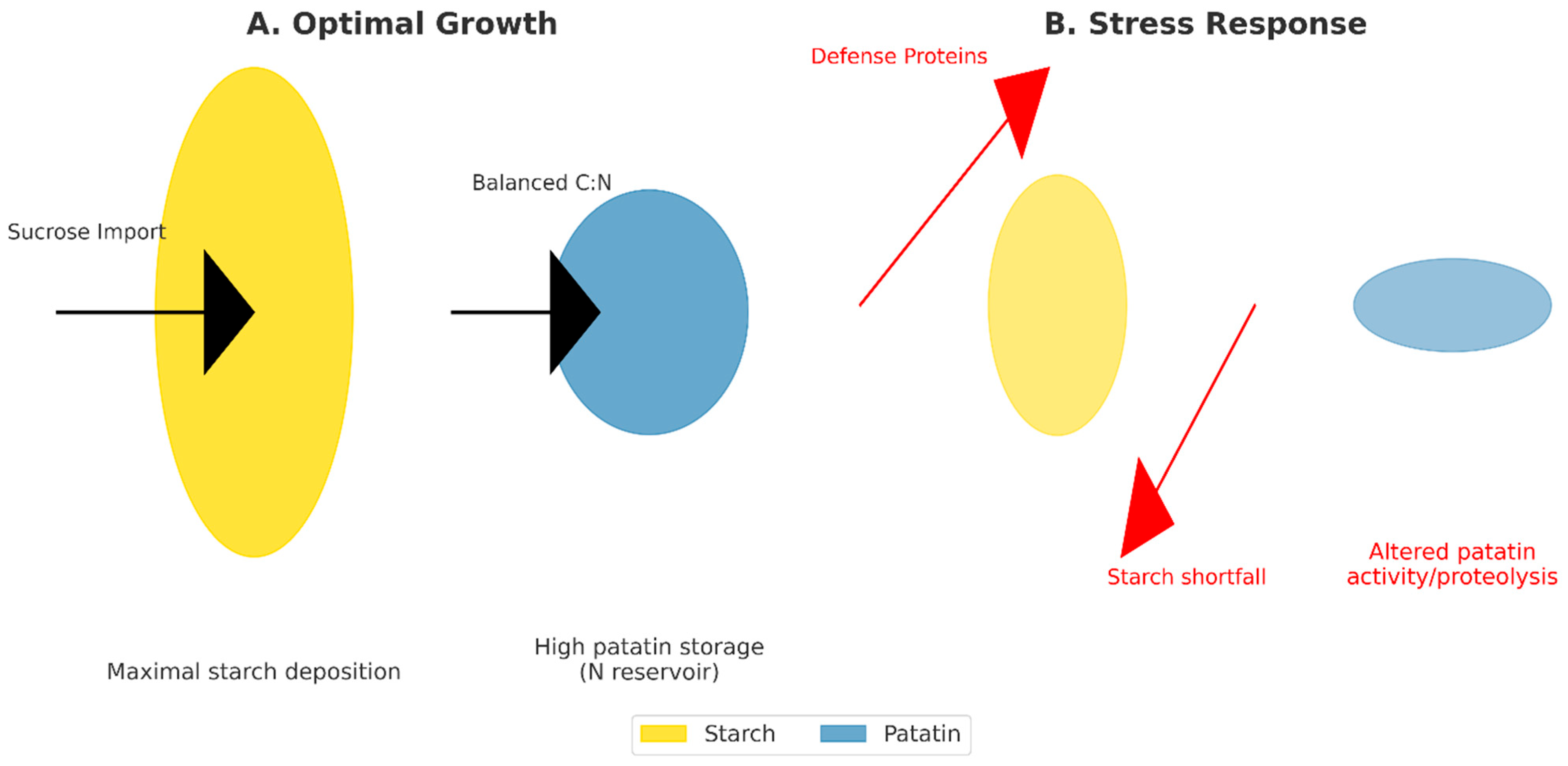

4. Patatin in Carbon Flux Allocation and Sink Strength

4.1. Conceptual Links Between Storage Protein and Carbon Economy

4.2. Mechanistic Hypotheses

4.3. Evidence Landscape

5. Interfaces with Starch Biosynthesis

5.1. Starch Pathway Refresher

5.2. How Patatin Modulate the Pathway

5.3. Data Gaps and Testable Predictions

6. Patatin Under Abiotic and Biotic Stresses

6.1. Drought

6.2. Salinity

6.3. Pathogen Attack (Fungi, Bacteria, Viruses) and Wounding

6.4. Synthesis—From Stress to Patatin to Reserves to Performance: Open Questions

7. Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

7.1. Isoform-Specific Functions and Redundancy

7.2. Need for Proximity Proteomics and Lipidomics

7.3. Sugar/Hormone–Patatin Regulatory Circuitry Under Fluctuating Environments

7.4. Multi-Omics + Fluxomics Under Realistic Field Stresses; Diurnal and Developmental Resolution

7.5. GWAS/Pan-Genome Mapping of Patatin Loci vs. Tuber Quality and Stress Traits

7.6. Standardized Stress Protocols and Cross-Study Comparability

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Z.; Huang, W. Reducing the Environmental Impact of Potato Farming through Sustainable Practices. J. Energy Biosci. 2025, 16, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Z.; Gao, M.; Liu, G.; Tian, S.; Zeng, F. The Global Potato-Processing Industry: A Review of Production, Products, Quality and Sustainability. Foods 2025, 14, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelis, L. Sink Strength as a Determinant of Dry Matter Partitioning in the Whole Plant. J. Exp. Bot. 1996, 47, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkar, K.; Singh, A. Metabolic and Physiological Functions of Patatin-Like Phospholipase—A in Plants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 287, 138474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D.L.; Beames, B.; Summers, M.D.; Park, W.D. Characterization of the Lipid Acyl Hydrolase Activity of the Major Potato (Solanum tuberosum) Tuber Protein, Patatin, by Cloning and Abundant Expression in a Baculovirus Vector. Biochem. J. 1988, 252, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racusen, D.; Foote, M. A Major Soluble Glycoprotein of Potato Tubers. J. Food Biochem. 1980, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P. Tuber Storage Proteins. Ann. Bot. 2003, 91, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Singh, S.; Green, A.G. High-Stearic and High-Oleic Cottonseed Oils Produced by Hairpin RNA-Mediated Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 1732–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydel, T.J.; Williams, J.M.; Krieger, E.; Moshiri, F.; Stallings, W.C.; Brown, S.M.; Pershing, J.C.; Purcell, J.P.; Alibhai, M.F. The Crystal Structure, Mutagenesis, and Activity Studies Reveal That Patatin Is a Lipid Acyl Hydrolase with a Ser-Asp Catalytic Dyad. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 6696–6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Caskurlu, S.; Kozan, K.; Kenney, R.H. Development of a Critical Appraisal Tool for Assessing the Reporting Quality of Qualitative Studies: A worked Example. Qual. Quant. 2023, 57, 1011–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, S.; Zinta, G. Genome Editing for Trait Improvement in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Genet. Eng. Crop Plants Food Health Secur. 2024, 2, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Guo, Q.; Akbar, S.; Zhi, Y.; El Tahchy, A.; Mitchell, M.; Li, Z.; Shrestha, P.; Vanhercke, T.; Ral, J.P.; et al. Genetic Enhancement of Oil Content in Potato Tuber (Solanum tuberosum L.) Through an Integrated Metabolic Engineering Strategy. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, D.; Firsov, A.; Timerbaev, V.; Kozlov, O.; Klementyeva, A.; Shaloiko, L.; Dolgov, S. Evaluation of Plant-Derived Promoters for Constitutive and Tissue-Specific Gene Expression in Potato. Plants 2020, 9, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignery, G.A.; Pikaard, C.S.; Park, W.D. Molecular Characterization of the Patatin Multigene Family of Potato. Gene 1988, 62, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, T.; Bai, X.; Liao, Z.; Chen, R.; Le, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Bian, X.; Wu, S.; Wu, J.; et al. Engineering Patatin for Enhanced Lipase Activity and Long-Chain Fatty Acid Specificity via Rational Design. Food Chem. 2025, 482, 144155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzo, D.; López-Pedrouso, M.; Bernal, J.; García, L.; Franco, D.; Zapata, C. Association of Patatin-Based Proteomic Distances with Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Quality Traits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 11864–11872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.; Mouzo, D.; López-Pedrouso, M.; Franco, D.; García, L.; Zapata, C. The Major Storage Protein in Potato Tuber Is Mobilized by a Mechanism Dependent on Its Phosphorylation Status. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grierson, C.; Du, J.S.; De Torres Zabala, M.; Beggs, K.; Smith, C.; Holdsworth, M.; Bevan, M. Separate Cis Sequences and Trans Factors Direct Metabolic and Developmental Regulation of a Potato Tuber Storage Protein Gene. Plant J. 1994, 5, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, R.A.; Kavanagh, T.A.; Bevan, M.W. GUS Fusions: Beta-glucuronidase as a Sensitive and Versatile Gene Fusion Marker in Higher Plants. EMBO J. 1987, 6, 3901–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Xiong, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Han, Z.; Li, K. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, Evolution and Expression Analysis of the DIR Gene Family in Potato (Solanum tuberosum). Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1224015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Pak, H.; Yan, T.; Chen, M.; Chen, X.; Wu, D.; Jiang, L. Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals a Patatin-Like Lipase Relating to the Reduction of Seed Oil Content in Brassica napus. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, K.; Zhao, K.; Cao, D.; Ma, Q.; Zhu, S.; Qu, C.; Ma, Y.; Gong, F.; et al. Genome Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of Patatin-Like Protein Family Members in Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Reprod. Breed. 2021, 1, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibarat, Z.; Saidi, A.; Shahbazi, M.; Zeinalabedini, M.; Gorji, A.M.; Mirzaei, M.; Salekdeh, G.H.; Ghaffari, M.R. Comparative Proteome Analysis of the Penultimate Internodes of Barley Genotypes Differing in Stem Reserve Remobilization Under Drought Stress. Research Square, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.T.; Yang, L.H.; Ferjani, A.; Lin, W.H. Multiple Functions of the Vacuole in Plant Growth and Fruit Quality. Mol. Hortic. 2021, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianna, G.R.; Cunha, N.B.; Rech, E.L. Soybean Seed Protein Storage Vacuoles for Expression of Recombinant Molecules. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2023, 71, 102331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, T.; Duan, E.; Bao, X.; Zhu, J.; Teng, X.; Zhang, P.; Gu, C.; et al. Endomembrane-Mediated Storage Protein Trafficking in Plants: Golgi-Dependent or Golgi-Independent? FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 2215–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, F.; Hofius, D.; Sonnewald, U. Intracellular Trafficking of Potato Leafroll Virus Movement Protein in Transgenic Arabidopsis. Traffic 2007, 8, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Tak, Y.; Bhatia, S.; Asthir, B.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Amarowicz, R. Crosstalk During the Carbon–Nitrogen Cycle That Interlinks the Biosynthesis, Mobilization and Accumulation of Seed Storage Reserves. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.; Sampaio, M.; Séneca, A.; Pereira, S.; Pissarra, J.; Pereira, C. Abiotic Stress Triggers the Expression of Genes Involved in Protein Storage Vacuole and Exocyst-Mediated Routes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, X.; Ma, R.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Si, H. Genome-Wide Analysis of NF-Y Genes in Potato and Functional Identification of StNF-YC9 in Drought Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 749688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yang, J.W.; Shim, D.; Kim, Y.H. Expression Analysis of Sweet Potato Patatin-Like Protein (PLP) Genes in Response to Infection with the Root Knot Nematode Meloidogyne Incognita. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2023, 17, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Z.; Gou, J.; Zhang, B.; Sun, X.; Xu, N. Patatin-Like Phospholipase A-Induced Alterations in Lipid Metabolism and Jasmonic Acid Production Affect the Heat Tolerance of Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis. Mar. Environ. Res. 2022, 179, 105688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geigenberger, P. Regulation of Starch Biosynthesis in Response to a Fluctuating Environment. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 1566–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zierer, W.; Rüscher, D.; Sonnewald, U.; Sonnewald, S. Tuber and Tuberous Root Development. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 551–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauw, G.; Nielsen, H.V.; Emmersen, J.; Nielsen, K.L.; Jørgensen, M.; Welinder, K.G. Patatins, Kunitz Protease Inhibitors and Other Major Proteins in Tuber of Potato Cv. Kuras. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 3569–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, L.E.; Paul, M.J.; Wingler, A. How Do Sugars Regulate Plant Growth and Development? New Insight Into the Role of Trehalose-6-Phosphate. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delatte, T.L.; Sedijani, P.; Kondou, Y.; Matsui, M.; de Jong, G.J.; Somsen, G.W.; Wiese-Klinkenberg, A.; Primavesi, L.F.; Paul, M.J.; Schluepmann, H. Growth Arrest by Trehalose-6-Phosphate: An Astonishing Case of Primary Metabolite Control Over Growth by Way of the SnRK1 Signaling Pathway. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloosterman, B.; Navarro, C.; Bijsterbosch, G.; Lange, T.; Prat, S.; Visser, R.G.F.; Bachem, C.W.B. StGA2ox1 Is Induced Prior to Stolon Swelling and Controls GA Levels During Potato Tuber Development. Plant J. 2007, 52, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yang, R.; Bartels, D.; Dong, T.; Duan, H. Roles of Abscisic Acid and Gibberellins in Stem/Root Tuber Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C.; Abelenda, J.A.; Cruz-Oró, E.; Cuéllar, C.A.; Tamaki, S.; Silva, J.; Shimamoto, K.; Prat, S. Control of Flowering and Storage Organ Formation in Potato by FLOWERING LOCUS T. Nature 2011, 478, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondhare, K.R.; Kumar, A.; Patil, N.S.; Malankar, N.N.; Saha, K.; Banerjee, A.K. Development of Aerial and Belowground Tubers in Potato Is Governed by Photoperiod and Epigenetic Mechanism. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernie, A.R.; Willmitzer, L. Molecular and Biochemical Triggers of Potato Tuber Development. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, D.M.; Timmerman, K.P.; Barry, G.F.; Preiss, J.; Kishoret, G.M. Regulation of the Amount of Starch in Plant Tissues by ADP Glucose Pyrophosphorylase. Science 1992, 258, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Prat, S.; Willmitzer, L.; Frommer, W.B. Cis Regulatory Elements Directing Tuber-Specific and Sucrose-Inducible Expression of a Chimeric Class I Patatin Promoter/GUS-Gene Fusion. MGG Mol. Gen. Genet. 1990, 223, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Shinozaki, K. Long-Distance Signaling in Plant Stress Response. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2019, 47, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Pu, X.; Jia, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, G.; Yang, Y.; Na, T.; Wang, J. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Multiple Effects of Nitrogen Accumulation and Metabolism in the Roots, Shoots, and Leaves of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Shan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, G. Transcriptomics Combined with Physiological Analysis and Metabolomics Revealed the Response of Potato Tuber Formation to Nitrogen. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fañanás-Pueyo, I.; Carrera-Castaño, G.; Pernas, M.; Oñate-Sánchez, L. Signalling and Regulation of Plant Development by Carbon/Nitrogen Balance. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhao, Y. The Critical Roles of Three Sugar-Related Proteins (HXK, SnRK1, TOR) in Regulating Plant Growth and Stress Responses. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Luo, L.; Xu, F.; Xu, X.; Bao, J. Carbohydrate Repartitioning in the Rice Starch Branching Enzyme IIb Mutant Stimulates Higher Resistant Starch Content and Lower Seed Weight Revealed by Multiomics Analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9802–9816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Wang, Y.; Pu, Z.; Shi, N.; Dormatey, R.; Wang, H.; Sun, C. Comprehensive Transcriptome and Proteome Analyses Reveal the Drought Responsive Gene Network in Potato Roots. Plants 2024, 13, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, R.; Ahmed, S.; Fan, W.; Yang, J.; Wu, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, P.; Yuan, L.; Wang, H. Engineering Properties of Sweet Potato Starch for Industrial Applications by Biotechnological Techniques Including Genome Editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- War, A.F.; Sheergojri, I.A.; Nanda, S.A.; Khan, M.A.; Rehmaan, I.U.; Reshi, Z.A.; Rashid, I. Recycling and Remobilization of Nitrogen During Senescence. In Advances in Plant Nitrogen Metabolism; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winck, F.V.; Monteiro, L.d.F.R.; Souza, G.M. Introduction: Advances in Plant Omics and Systems Biology. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1346, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Huang, X.; Su, X.; Zhu, G.; Zheng, L.; Lin, J.; Wang, J.; Xue, H. Potato: From Functional Genomics to Genetic Improvement. Mol. Hortic. 2024, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Pan, Y.; Liu, H.; Cheng, Z. Melatonin Interaction with Abscisic Acid in the Regulation of Abiotic Stress in Solanaceae Family Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1271137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Shi, M.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Qin, S.; Kang, Y. Dynamics of Physiological and Biochemical Effects of Heat, Drought and Combined Stress on Potato Seedlings. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fünfgeld, M.M.F.F.; Wang, W.; Ishihara, H.; Arrivault, S.; Feil, R.; Smith, A.M.; Stitt, M.; Lunn, J.E.; Niittylä, T. Sucrose Synthases Are Not Involved in Starch Synthesis in Arabidopsis Leaves. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, F.; Galani, S.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Zhao, P.; Lu, X.; Lin, X.; Xu, C.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Liu, X. Current Perspectives on the Regulatory Mechanisms of Sucrose Accumulation in Sugarcane. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debast, S.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Hajirezaei, M.R.; Hofmann, J.; Sonnewald, U.; Fernie, A.R.; Börnke, F. Altering Trehalose-6-Phosphate Content in Transgenic Potato Tubers Affects Tuber Growth and Alters Responsiveness to Hormones During Sprouting. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1754–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, N.; Yamamoto, Y.Y. Primary Metabolism and Transcriptional Regulation in Higher Plants. Rev. Agric. Sci. 2021, 9, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toinga-Villafuerte, S.; Vales, M.I.; Awika, J.M.; Rathore, K.S. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Mutagenesis of the Granule-Bound Starch Synthase Gene in the Potato Variety Yukon Gold to Obtain Amylose-Free Starch in Tubers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renna, L.; Papini, A.; Mancuso, S.; Brandizzi, F.; Stefano, G. Plant Plastids: From Evolutionary Origins to Functional Specialization and Organelle Interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 77, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huercano, C.; Moya-Barrientos, M.; Cuevas, O.; Sanchez-Vera, V.; Ruiz-Lopez, N. ER–Plastid Contact Sites as Molecular Crossroads for Plastid Lipid Biosynthesis. BMC Biol. 2025, 23, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, Y.P.; Oelmüller, R. Lipid Peroxidation and Stress-Induced Signalling Molecules in Systemic Resistance Mediated by Azelaic Acid/AZELAIC ACID INDUCED1: Signal Initiation and Propagation. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 30, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffeiner, M.; Zhu, S.; González-Fuente, M.; Üstün, S. Interplay Between Autophagy and Proteasome During Protein Turnover. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, U.; Lu, S.; Fadlalla, T.; Iqbal, S.; Yue, H.; Yang, B.; Hong, Y.; Wang, X.; Guo, L. The Functions of Phospholipases and Their Hydrolysis Products in Plant Growth, Development and Stress Responses. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 86, 101158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.B.; Borradaile, N.M. Mushrooms and Cardiovascular Protection: Molecular, Cellular, and Physiological Aspects. In Ancient and Traditional Foods, Plants, Herbs and Spices Used in Cardiovascular Health and Disease; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tang, B.; Ren, R.; Wu, M.; Liu, F.; Lv, Y.; Shi, T.; Deng, J.; Chen, Q. Understanding the Potential Gene Regulatory Network of Starch Biosynthesis in Tartary Buckwheat by RNA-Seq. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, T.; Su, X.; He, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Qu, H. ATP Homeostasis and Signaling In Plants. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Wang, H.; Yu, H.; Li, H.; Yi, D.; Ikram, S.; Cao, Y.D.; Zhao, C.; Lu, T.; Li, Y.; et al. Trehalose-6-Phosphate Phosphatase SlTPP1 Adjusts Diurnal Carbohydrate Partitioning in Tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 6213–6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.; Ma, Z.; Chen, H.; Gao, H. Toward an Understanding of Potato Starch Structure, Function, Biosynthesis, and Applications. Food Front. 2023, 4, 980–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanat, R.; Shamekova, M.; Sapakhova, Z.; Toishimanov, M.; Daurov, D.; Raissova, N.; Abilda, Z.; Daurova, A.; Zhambakin, K. Gene Expression Analysis for Drought Tolerance in Early Stage of Potato Plant Development. Biology 2024, 13, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrajeh, S.; Khan, M.; Putra, A.; Al-Ugaili, D.N.; Alobaidi, K.H.; Al Dossary, O.; Al-Obaidi, J.R.; Jamaludin, A.A.; Allawi, M.Y.; Al-Taie, B.S.; et al. Mapping Proteomic Response to Salinity Stress Tolerance in Oil Crops: Towards Enhanced Plant Resilience. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2024, 22, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Munoz, L.; Nielsen, S.; Corredig, M. Changes in Potato Peptide Bioactivity After Gastrointestinal Digestion. An In Silico and In Vitro Study of Different Patatin-Rich Potato Protein Isolate Matrices. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 4, 100679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, G.; Piibor, J.; Midekessa, G.; Godakumara, K.; Dissanayake, K.; Andronowska, A.; Bhat, R.; Fazeli, A. Systematic Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles from Potato (Solanum tuberosum cv. Laura) Roots and Peels: Biophysical Properties and Proteomic Profiling. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1477614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Tang, Z.; Sardar, M.F.; Yu, Y.; Ai, K.; Liang, S.; Alkahtani, J.; Lyv, D. Unveiling the Frontiers of Potato Disease Research Through Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1430066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, M.; Ozón, B.; González, S.V.; García-Pardo, J.; Obregón, W.D. Plant Protease Inhibitors as Emerging Antimicrobial Peptide Agents: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Yang, S.; Ruan, B.; Ye, G.; He, M.; Su, W.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, S. Research Progress on Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Mechanisms of Potato in Response to Drought and High Temperature. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourasia, K.N.; Lal, M.K.; Tiwari, R.K.; Dev, D.; Kardile, H.B.; Patil, V.U.; Kumar, A.; Vanishree, G.; Kumar, D.; Bhardwaj, V.; et al. Salinity Stress in Potato: Understanding Physiological, Biochemical and Molecular Responses. Life 2021, 11, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharte, J.; Hassa, S.; Herrfurth, C.; Feussner, I.; Forlani, G.; Weis, E.; von Schaewen, A. Metabolic Priming in G6PDH Isoenzyme-Replaced Tobacco Lines Improves Stress Tolerance and Seed Yields via Altering Assimilate Partitioning. Plant J. 2023, 116, 1696–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrenner, R.; Verwaaijen, B.; Genzel, F.; Flemer, B.; Grosch, R. Transcriptional Changes in Potato Sprouts Upon Interaction with Rhizoctonia solani Indicate Pathogen-Induced Interference in the Defence Pathways of Potato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, H.; Mizubayashi, T.; Kitazawa, N.; Yamanouchi, U.; Ando, T.; Mukai, Y.; Shimosaka, E.; Noda, T.; Asano, K.; Akai, K.; et al. Polyploid QTL-Seq Identified QTLs Controlling Potato Flesh Color and Tuber Starch Phosphorus Content in a Plexity-Dependent Manner. Breed. Sci. 2024, 74, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Dhaka, N.; Krishnan, K.; Yadav, G.; Priyam, P.; Sharma, M.K.; Sharma, R.A. Temporal Gene Expression Profiles From Pollination to Seed Maturity in Sorghum Provide Core Candidates for Engineering Seed Traits. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 2662–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Guo, S.; Lu, S.; Gong, J.; Wang, L.; Ding, L.; Chen, Q.; Liu, W. The Development of Proximity Labeling Technology and Its Applications in Mammals, Plants, and Microorganisms. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, D.; Gao, C. TurboID-Based Proximity Labeling Accelerates Discovery of Neighboring Proteins in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2024, 29, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanford, J.; Zhai, Z.; Baer, M.D.; Guo, G.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q.; Raugei, S.; Shanklin, J. Molecular Mechanism of Trehalose 6-Phosphate Inhibition of the Plant Metabolic Sensor Kinase SnRK1. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artins, A.; Martins, M.C.M.; Meyer, C.; Fernie, A.R.; Caldana, C. Sensing and Regulation of C and N Metabolism–Novel Features and Mechanisms of the TOR and SnRK1 Signaling Pathways. Plant J. 2024, 118, 1268–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah Slater, K.; Beyß, M.; Xu, Y.; Barber, J.; Costa, C.; Newcombe, J.; Theorell, A.; Bailey, M.J.; Beste, D.J.V.; McFadden, J.; et al. One-Shot 13C15N-Metabolic Flux Analysis for Simultaneous Quantification of Carbon and Nitrogen Flux. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2023, 19, e11099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappetta, E.; Del Regno, C.; Ceccacci, S.; Monti, M.C.; Spinelli, L.; Conte, M.; D’Anna, C.; Alfieri, M.; Vietri, M.; Costa, A.; et al. Proteome Reprogramming and Acquired Stress Tolerance in Potato Cells Exposed to Acute or Stepwise Water Deficit. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 2875–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F. Genome-Wide Association Studies for Key Agronomic and Quality Traits in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Agronomy 2024, 14, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach | Patatin-Related Observation | Starch/Quality Trait Measured | Key Findings | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systems biology & metabolic flux analysis | Patatin expression correlated with sink strength during tuber bulking | Dry matter and starch accumulation | Strong positive correlation between patatin abundance and tuber dry matter/starch levels | [55] |

| qPCR & physiological assays under drought stress | Stress suppressed patatin expression while starch biosynthesis was downregulated | Dry matter and starch quality | Reduction in patatin linked with decreased starch and tuber quality under drought | [56] |

| Transgenic manipulation of sucrose signaling | Altered SnRK1/T6P balance influenced patatin expression | Starch content and quality traits | Patatin expression tracked with sugar signaling changes that modulated starch accumulation | [57] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis of patatin isoforms | Knockout of class I patatin reduced starch accumulation efficiency | Starch yield, amylose/amylopectin ratio | Loss of patatin disrupted starch partitioning, lowering starch yield and altering composition | [58] |

| Enzyme/Node | Primary Function in Starch Biosynthesis | Known Regulatory Inputs/Control Points | Hypothesized Connection to Patatin (Direct/Indirect) | Representative Recent References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose synthase (SuSy) | Produces UDP-glucose, contributing to ADP-glucose pool for starch synthesis. | Regulated by sucrose flux, oxygen status, and sink strength. | Indirect: Patatin-mediated vacuolar storage may enhance sink demand, indirectly promoting SuSy activity. | [2,50] |

| Cell wall/vacuolar invertases | Cleave sucrose to glucose + fructose, establishing osmotic gradients. | Controlled by sucrose, invertase inhibitors, and developmental stage. | Indirect: Patatin affects vacuolar osmotic balance, influencing hexose signaling during bulking. | [2,50,59] |

| ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) | Gateway enzyme producing ADP-Glc for starch synthesis. | Allosterically regulated by 3-PGA/Pi; redox and phosphorylation-sensitive. | Indirect: Patatin influences sugar signaling (T6P/SnRK1) and N status, modulating AGPase activation. | [65,71,72] |

| Granule-bound starch synthase I (GBSSI) | Catalyzes amylose biosynthesis in starch granules. | Expression and plastid targeting regulated by substrate availability. | Indirect: Patatin-driven sink demand alters ADP-Glc pools; lipid/oxylipin signals from PLA activity may influence plastidial GBSSI. | [70,73] |

| Soluble starch synthases (SS), Starch branching enzymes (SBE), Isoamylases (ISA) | Construct amylopectin and determine granule structure. | Isoform-specific expression and protein–protein interactions; regulated by phosphorylation. | Indirect: Patatin impacts ATP/redox/amino acid availability, influencing SS/SBE/ISA activity. | [70,73] |

| T6P/SnRK1 axis | Sugar-sensing module controlling anabolic vs. catabolic fluxes; influences AGPase. | T6P levels reflect sucrose status; SnRK1 regulates metabolic gene expression. | Indirect → direct: Patatin expression is sucrose-responsive and feeds back through N remobilization, affecting T6P/SnRK1 balance. | [2,50,59] |

| Species/Cultivar | Stress Regime | Patatin Readouts | Starch/DM Outcomes | Yield/Quality Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solanum tuberosum cv. Désirée | Drought (greenhouse; moderate vs. severe) | Transcript & protein levels under severe drought; PLA-like activity (lipid remodeling) | Reduced starch accumulation, soluble sugars (osmoprotection) | Lower tuber DM; yield penalties under severe stress | [80] |

| S. tuberosum cv. Kufri Jyoti | Salinity (NaCl 100 mM, hydroponics) | Patatin protein stability compromised; partial proteolysis observed | Decline in starch content, reduced specific gravity | Lower dry matter; increased ionic stress damage | [81] |

| S. tuberosum cv. Atlantic | ABA treatment mimicking drought signal | Patatin gene expression induced early, but protein turnover accelerated | Transient starch decline, sucrose retention in tuber parenchyma | Tuber bulking slowed; altered partitioning | [82] |

| S. tuberosum (wild accession: S. chacoense) | Pathogen (Phytophthora infestans) infection | Patatin isoforms upregulated in leaves and tuber periphery; lipid mediators released | Starch deposition inhibited near lesions | Yield loss due to defense prioritization; patatin linked to hypersensitive response | [83] |

| S. tuberosum cv. Russet Burbank | Mechanical wounding (postharvest storage test) | Wound-inducible patatin proteins; proteolysis after 48 h | Starch hydrolysis stimulated at wound sites | Quality loss: sweetening and textural changes | [50] |

| S. tuberosum cv. Innovator | Combined drought + heat stress (field trial) | RNA-seq: patatin transcripts; stress chaperones | Significant starch shortfall; amylopectin/amylose ratio altered | DM reduction; fry color defects; yield | [58] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y. The Multifunctional Role of Patatin in Potato Tuber Sink Strength, Starch Biosynthesis, and Stress Adaptation: A Systematic Review. Biology 2026, 15, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010029

Wu Y, Zeng Y, Zhang W, Zhou Y. The Multifunctional Role of Patatin in Potato Tuber Sink Strength, Starch Biosynthesis, and Stress Adaptation: A Systematic Review. Biology. 2026; 15(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yicong, Yunxia Zeng, Wenying Zhang, and Yonghong Zhou. 2026. "The Multifunctional Role of Patatin in Potato Tuber Sink Strength, Starch Biosynthesis, and Stress Adaptation: A Systematic Review" Biology 15, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010029

APA StyleWu, Y., Zeng, Y., Zhang, W., & Zhou, Y. (2026). The Multifunctional Role of Patatin in Potato Tuber Sink Strength, Starch Biosynthesis, and Stress Adaptation: A Systematic Review. Biology, 15(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010029