Genome-Wide Identification and Comprehensive Analysis of the GS Gene Family in Hordeum vulgare Under Low Nitrogen Stress

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials, Hydroponic Treatments and Sampling

2.2. Genomic Resources and Gene Identification

2.3. Physicochemical Properties, Subcellular Localization and Chromosomal Localization

2.4. Gene Structure, Conserved Motifs and Promoter Analysis

2.5. Phylogenetic Reconstruction and Covariance Analysis

2.6. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Fluorescence Quantification, Read Segment Alignment, Expression Quantification and Differential Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Identification, Physicochemical Characterization and Chromosomal Localization of GS Genes in Barley

3.2. Gene Structure and Distribution of Conserved Motifs

3.3. Promoter Cis-Regulatory Elements and Potential Transcriptional Responsiveness

3.4. Phylogenetic Localization and Protein–Protein Interaction Prediction

3.5. Tertiary Structure Modeling and Validation of Conserved Structural Domains

3.6. Co-Linearity Relationships and Evolutionary Constraints

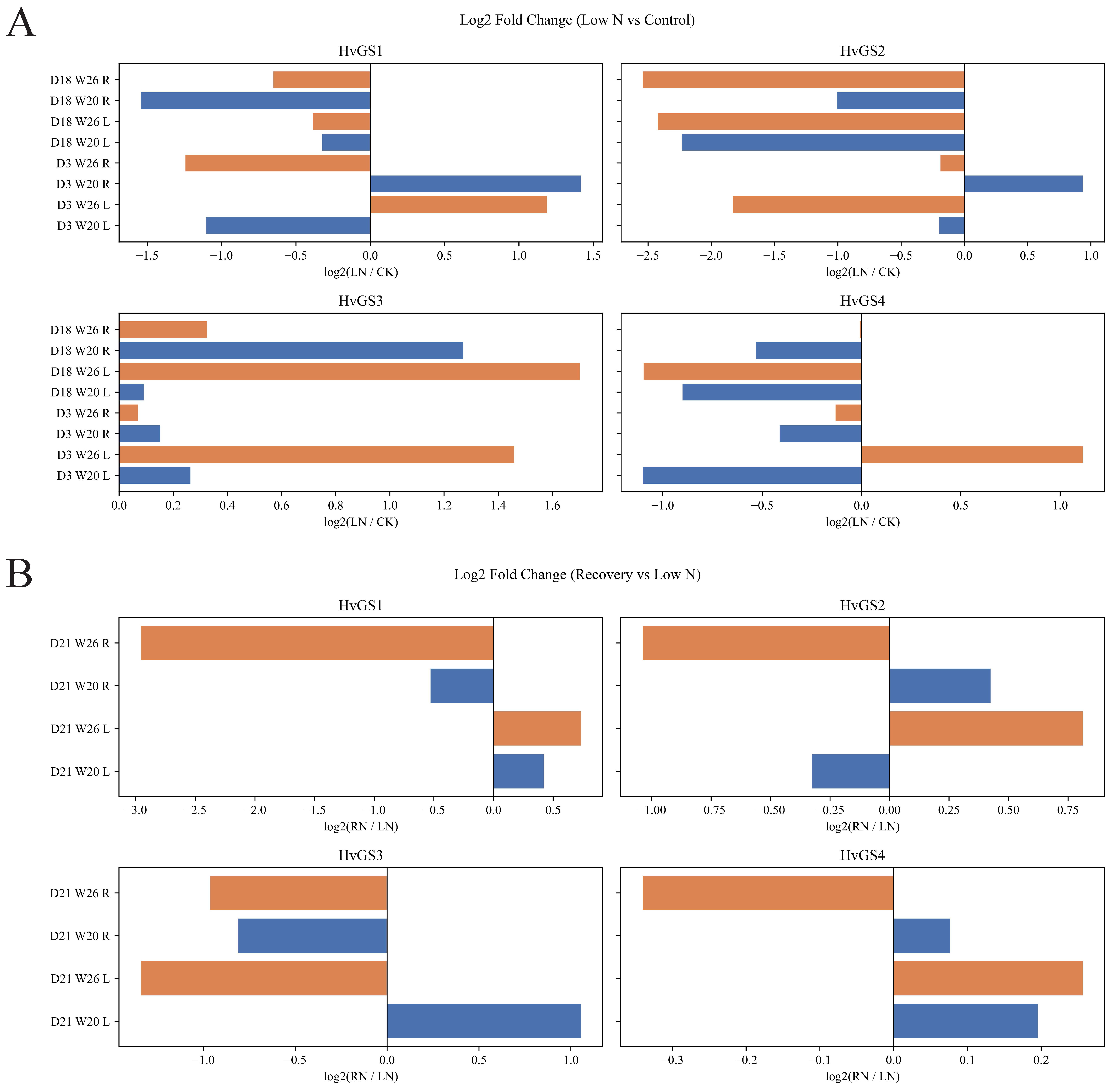

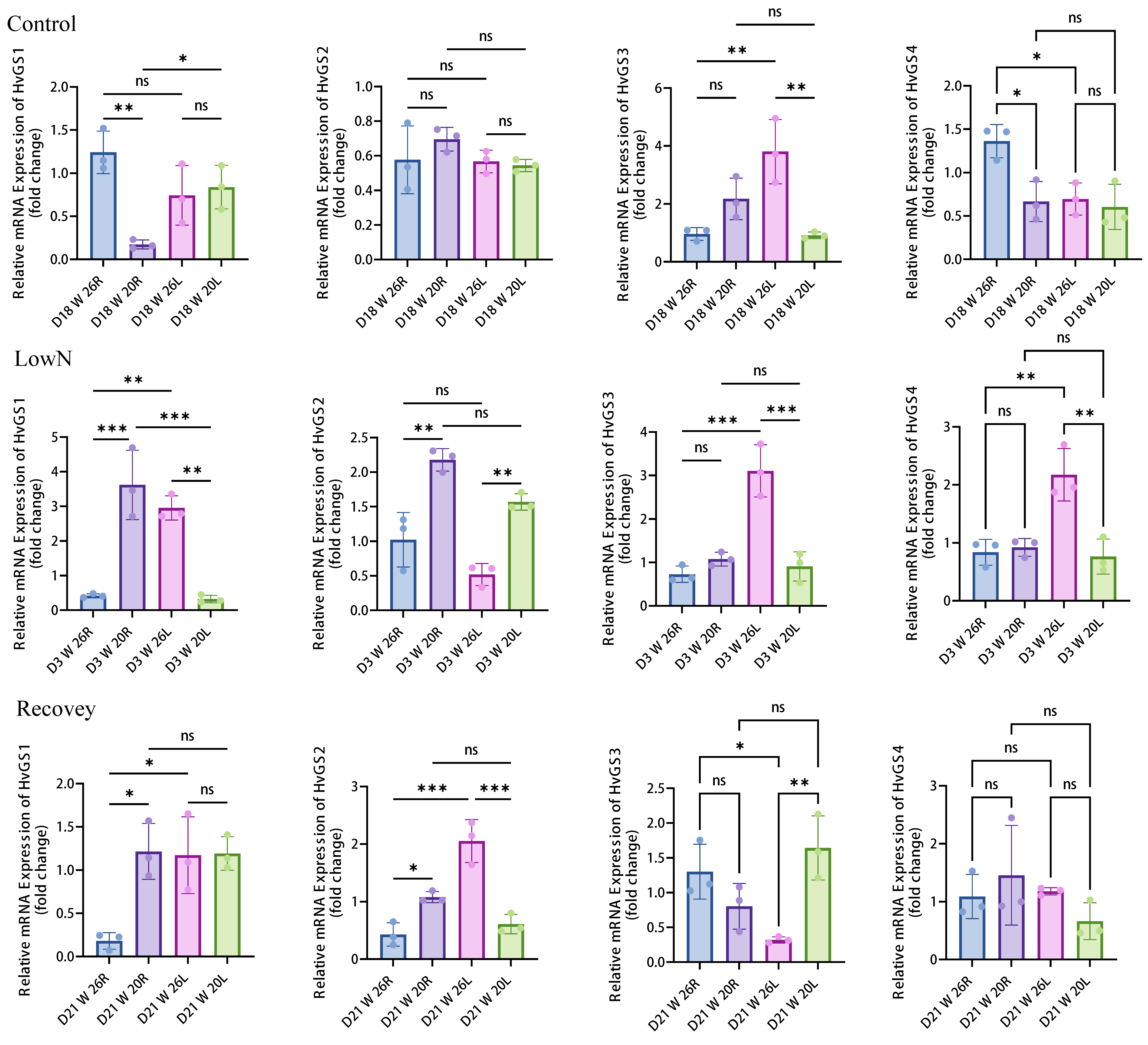

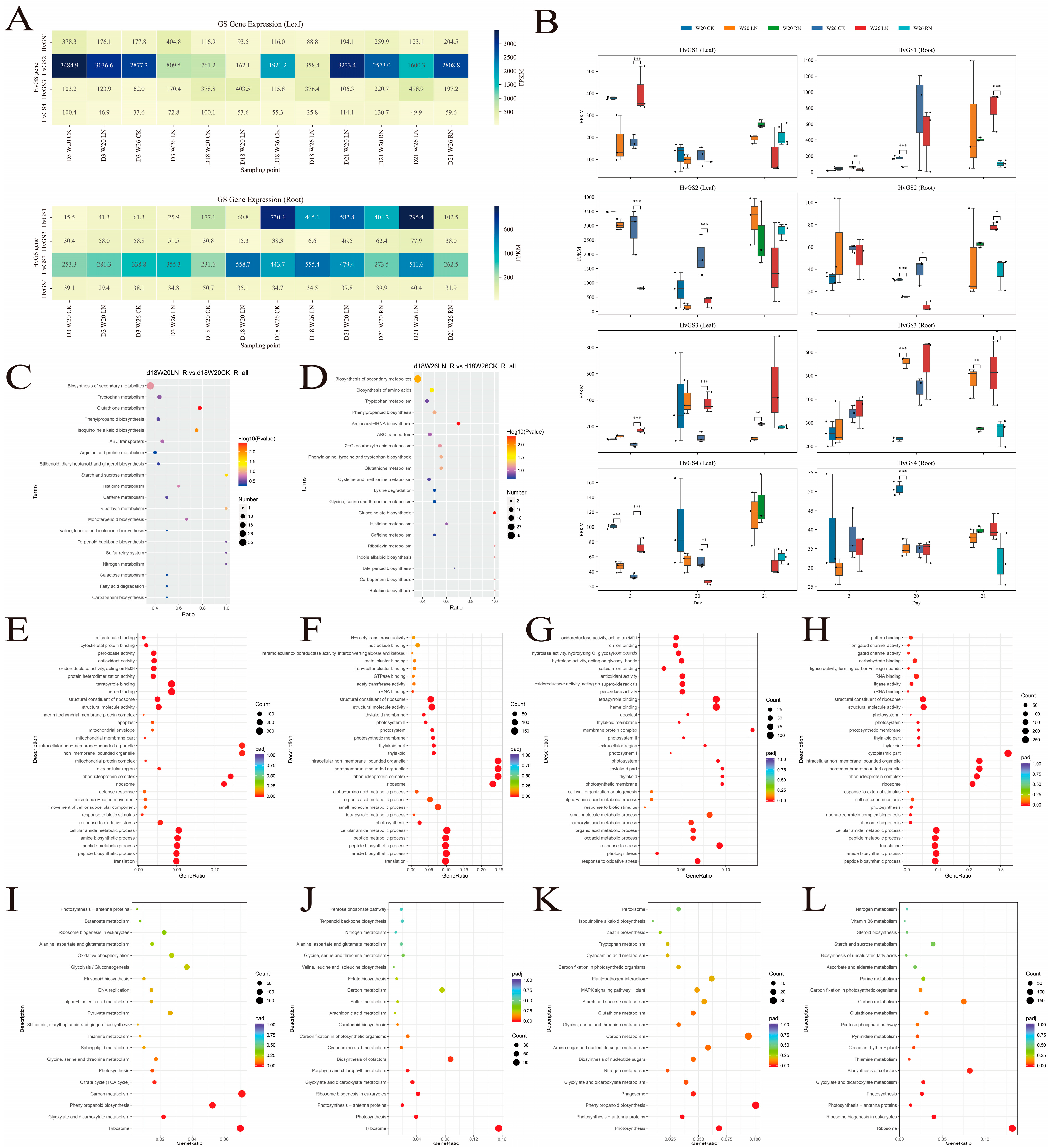

3.7. Expression Profiling of HvGS Genes Under Different Nitrogen Treatments

3.8. Transcriptome and Metabolome GO/KEGG Enrichment Analyses Under Low Nitrogen Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Good, A.G.; Beatty, P.H. Fertilizing Nature: A Tragedy of Excess in the Commons. PLoS Biol. 2011, 9, e1001124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkesford, M.J. Reducing the carbon footprint of crop production: Use of nitrogen. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 2002–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Miller, A.J. Plant Nitrogen Assimilation and Use Efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, S.; Bi, Y.M.; Rothstein, S.J. Understanding plant response to nitrogen limitation for the improvement of crop nitrogen use efficiency. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011, 9, 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The, S.V.; Snyder, R.; Tegeder, M. Targeting Nitrogen Metabolism and Transport Processes to Improve Plant Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 628366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masclaux-Daubresse, C.; Daniel-Vedele, F.; Dechorgnat, J.; Chardon, F.; Gaufichon, L.; Suzuki, A. Nitrogen uptake, assimilation and remobilization in plants: Challenges for sustainable and productive agriculture. Ann. Bot. 2010, 105, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapp, A. Plant nitrogen assimilation and its regulation: A complex puzzle with missing pieces. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 25, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Cheng, Y.H.; Chen, K.E.; Tsay, Y.F. Nitrate transport, signaling, and use efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 85–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Tang, H.; Zhang, X. Nitrate transporters in plants: Structure, function and regulation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, D.T.; Kronzucker, H.J. NH4+ toxicity in higher plants: A critical review. J. Plant Physiol. 2002, 159, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Okamoto, M.; Beatty, P.H.; Rothstein, S.J.; Good, A.G. The genetics of nitrogen use efficiency in crop plants. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2015, 49, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miflin, B.J.; Habash, D.Z. The role of glutamine synthetase and glutamate dehydrogenase in nitrogen assimilation and recycling. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas, R.A.; Quilleré, I.; Lea, P.J.; Hirel, B. Analysis of nitrogen metabolism in maize kernels under nitrogen limitation. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1863–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusano, M.; Fukushima, A.; Redestig, H.; Saito, K. Metabolomic approaches toward understanding nitrogen metabolism in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 1439–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: A multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funck, D.; Eckard, S.; Müller, G. Non-redundant functions of two proline dehydrogenase isoforms in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, S.M.; Habash, D.Z. The importance of cytosolic glutamine synthetase in nitrogen assimilation and recycling. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirel, B.; Tétu, T.; Lea, P.J.; Dubois, F. Improving nitrogen use efficiency in crops for sustainable agriculture. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1452–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, H.C.; Eriksson, D.; Møller, I.S.; Schjoerring, J.K. Cytosolic glutamine synthetase: A target for improvement of crop nitrogen use efficiency? Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Lee, J.; Kichey, T.; Gerentes, D.; Zivy, M.; Tatout, C.; Dubois, F.; Balliau, T.; Valot, B.; Davanture, M.; et al. Two cytosolic glutamine synthetase isoforms of maize are specifically involved in the control of grain production. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 3252–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unno, H.; Uchida, T.; Sugawara, H.; Kurisu, G.; Sugiyama, T.; Yamaya, T.; Sakakibara, H.; Hase, T.; Kusunoki, M. Atomic structure of plant glutamine synthetase: A key enzyme for plant productivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 29287–29296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, M.; Ishiyama, K.; Kojima, S.; Konishi, N.; Nakano, K.; Kanno, K.; Hayakawa, T.; Yamaya, T. Asparagine synthetase1, but not asparagine synthetase2, is responsible for the biosynthesis of asparagine following the supply of ammonium to rice roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.E.; Ribeiro, C.W.; Martins, M.O.; Bonifacio, A.; Staats, C.C.; Andrade, C.M.; Cerqueira, J.V.; Margis-Pinheiro, M.; Silveira, J.A. Cytosolic APX knockdown rice plants sustain photosynthesis by regulation of protein expression related to photochemistry, Calvin cycle and photorespiration. Physiol Plant. 2014, 150, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaya, T.; Kusano, M. Evidence supporting distinct functions of glutamine synthetase isoforms in rice. Plant Sci. 2014, 225, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothier, J.; Gaufichon, L.; Sormani, R.; Lemaître, T.; Azzopardi, M.; Morin, H.; Chardon, F.; Reisdorf-Cren, M.; Belcram, K.; Héricourt, F.; et al. The cytosolic glutamine synthetase GLN1;2 plays a role in the control of plant growth and ammonium homeostasis in Arabidopsis rosettes when nitrate supply is not limiting. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 1375–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masclaux-Daubresse, C.; Reisdorf-Cren, M.; Orsel, M. Leaf nitrogen remobilisation for plant growth and seed filling. Plant Biol. 2008, 10, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Rodríguez, V.; García-Gutiérrez, A.; Canales, J.; Ávila, C.; Cánovas, F.M. The glutamine synthetase gene family in Populus sp.: Functional analysis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011, 52, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapp, A.; Berthomé, R.; Orsel, M.; Mercey-Boutet, S.; Yu, A.; Castaings, L.; Elftieh, S.; Major, H.; Renou, J.P.; Daniel-Vedele, F. Arabidopsis roots and shoots show distinct temporal adaptation patterns toward nitrogen starvation. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 1255–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, A.; Zhao, Z.; Ding, G.; Shi, L.; Xu, F.; Cai, H. Accumulated expression level of cytosolic glutamine synthetase 1 gene (OsGS1;1 or OsGS1;2) alter plant development and the carbon-nitrogen metabolic status in rice. PLoS ONE 2014, 17, e95581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelli, M.; Duo, Y.; Konda, A.R.; Liu, K.; Zhang, C.; Clemente, T.E.; Holding, D.R. Identification of nitrogen deficiency-responsive genes in sorghum using RNA-Seq analysis. Plant Sci. 2014, 223, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Coruzzi, G.M.; Bush, D.R. Nitrogen and carbon nutrient and metabolite signaling in plants. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, B.G.; Lea, P.J. Glutamate in plants: Metabolism, regulation, and signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 2339–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, A.R.; Carvalho, H.G. Novel aspects of glutamine synthetase regulation in N2-fixing legume nodules. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiba, T.; Kudo, T.; Kojima, M.; Sakakibara, H. Hormonal control of nitrogen acquisition: Roles of auxin, abscisic acid, and cytokinin. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P. Dancing with hormones: A current perspective of nitrate signaling and regulation in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulpice, R.; Pyl, E.T.; Ishihara, H.; Trenkamp, S.; Steinfath, M.; Witucka-Wall, H.; Gibon, Y.; Usadel, B.; Poree, F.; Piques, M.; et al. Starch as a major integrator in the regulation of plant growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 10348–10353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araus, J.L.; Kefauver, S.C.; Zaman-Allah, M.; Olsen, M.S.; Cairns, J.E. Translating high-throughput phenotyping into genetic gain. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, P.H.; Good, A.G. Future prospects for cereals that fix nitrogen. Science 2011, 333, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Hu, B.; Chu, C. Nitrogen use efficiency in crops: Lessons from Arabidopsis and rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2477–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaufichon, L.; Masclaux-Daubresse, C.; Tcherkez, G.; Reisdorf-Cren, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Hase, T.; Suzuki, A. Arabidopsis thaliana ASN2 encoding asparagine synthetase is involved in the control of nitrogen assimilation. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 4095–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schjoerring, J.K.; Husted, S.; Mäck, G.; Mattsson, M. The regulation of ammonium translocation in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes-Nesi, A.; Fernie, A.R.; Stitt, M. Metabolic and signaling interactions between nitrogen and carbon in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, C.; Hammond, J.P.; White, P.J.; Verbruggen, N. How do plants respond to nutrient shortage by biomass allocation? Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, T.; Gaufichon, L.; Boutet-Mercey, S.; Christ, A.; Masclaux-Daubresse, C. Enzymatic and metabolic diagnostic of nitrogen deficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 1056–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mur, L.A.J.; Simpson, C.; Kumari, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Gupta, K.J. Moving nitrogen to the centre of plant defence against pathogens. Ann. Bot. 2017, 119, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, M.; Hudson, D.; Schofield, A.; Tsao, R.; Yang, R.; Gu, H.; Bi, Y.M.; Rothstein, S.J. Adaptation of Arabidopsis to nitrogen limitation involves induction of anthocyanin synthesis controlled by the NLA gene. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2933–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene ID | Number of Amino Acid | Molecular Weight | Theoretical pI | Instability Index | Aliphatic Index | Grand Average of Hydropathicity | Subcellular Localization Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HvGS1 | 427 | 46,688.81 | 5.75 | 37.99 | 78.83 | −0.338 | Chloroplast |

| HvGS4 | 356 | 39,127.14 | 5.31 | 34.38 | 75.06 | −0.403 | Cytoplasm |

| HvGS3 | 354 | 38,774.74 | 5.71 | 34.86 | 78.84 | −0.364 | Cytoplasm |

| HvGS2 | 362 | 39,709.65 | 5.96 | 37.58 | 73.07 | −0.462 | Cytoplasm |

| Gene ID | Alpha Helix (Hh) | Extended Strand (Ee) | Beta Turn (Tt) | Random Coil (Cc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HvGS1 | 29.74 | 14.29 | 3.04 | 52.93 |

| HvGS4 | 29.49 | 17.7 | 2.53 | 50.28 |

| HvGS3 | 30.79 | 18.08 | 1.98 | 49.15 |

| HvGS2 | 29.28 | 18.51 | 0 | 52.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pei, Y.; Wang, J.; Yao, L.; Si, E.; Yang, K.; Li, B.; Meng, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, H.; Shang, X.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Comprehensive Analysis of the GS Gene Family in Hordeum vulgare Under Low Nitrogen Stress. Biology 2025, 14, 1789. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121789

Pei Y, Wang J, Yao L, Si E, Yang K, Li B, Meng Y, Ma X, Zhang H, Shang X, et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Comprehensive Analysis of the GS Gene Family in Hordeum vulgare Under Low Nitrogen Stress. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1789. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121789

Chicago/Turabian StylePei, Yaping, Juncheng Wang, Lirong Yao, Erjing Si, Ke Yang, Baochun Li, Yaxiong Meng, Xiaole Ma, Hong Zhang, Xunwu Shang, and et al. 2025. "Genome-Wide Identification and Comprehensive Analysis of the GS Gene Family in Hordeum vulgare Under Low Nitrogen Stress" Biology 14, no. 12: 1789. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121789

APA StylePei, Y., Wang, J., Yao, L., Si, E., Yang, K., Li, B., Meng, Y., Ma, X., Zhang, H., Shang, X., & Wang, H. (2025). Genome-Wide Identification and Comprehensive Analysis of the GS Gene Family in Hordeum vulgare Under Low Nitrogen Stress. Biology, 14(12), 1789. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121789