Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of the Endemic and Medicinal Plant Zingiber salarkhanii: Comparative Analysis and Phylogenetic Relationships

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials, DNA Extraction

2.2. Sequencing and Assembly

2.3. Gene Annotation

2.4. Codon Usage Bias and RNA Editing Site

2.5. SSR and Long Repeat Analyses

2.6. IR Contraction/Expansion and Genome Divergence

2.7. Phylogenetic Analysis in Cp Genomes

3. Results

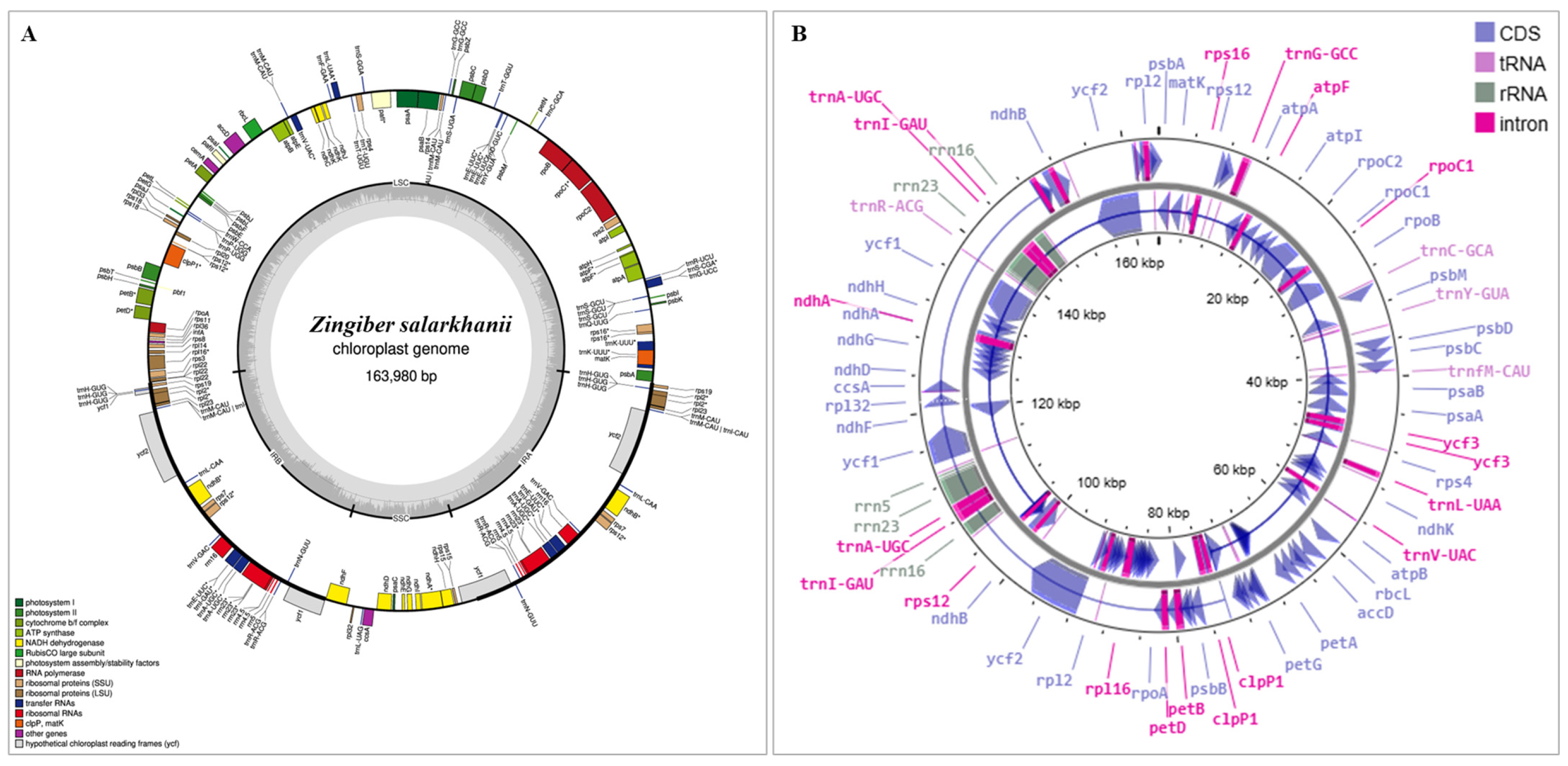

3.1. General Characteristics of Z. salarkhanii

3.2. Codon Usage Bias and RNA Editing

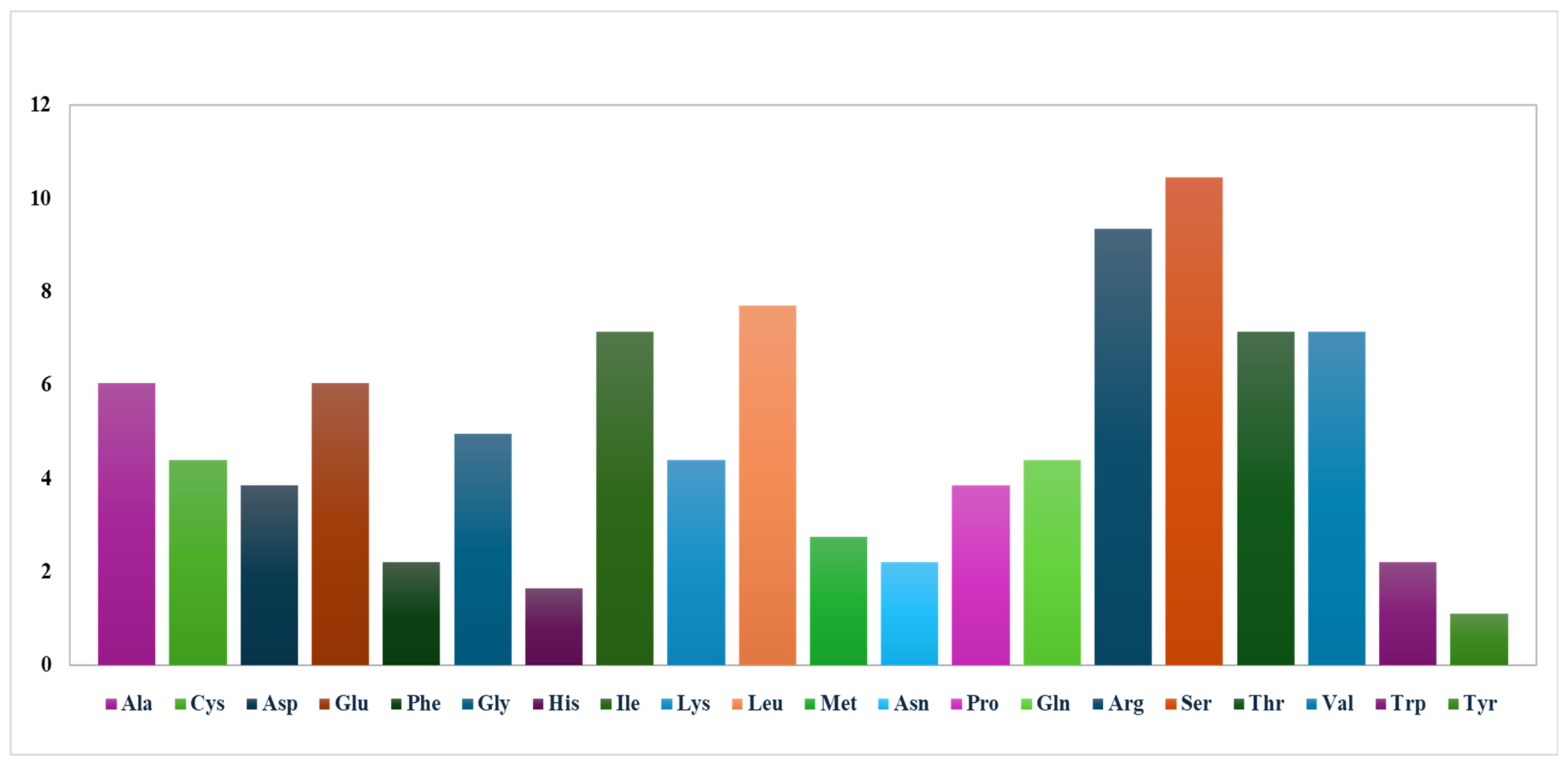

3.2.1. RCSU and RFSC Analysis

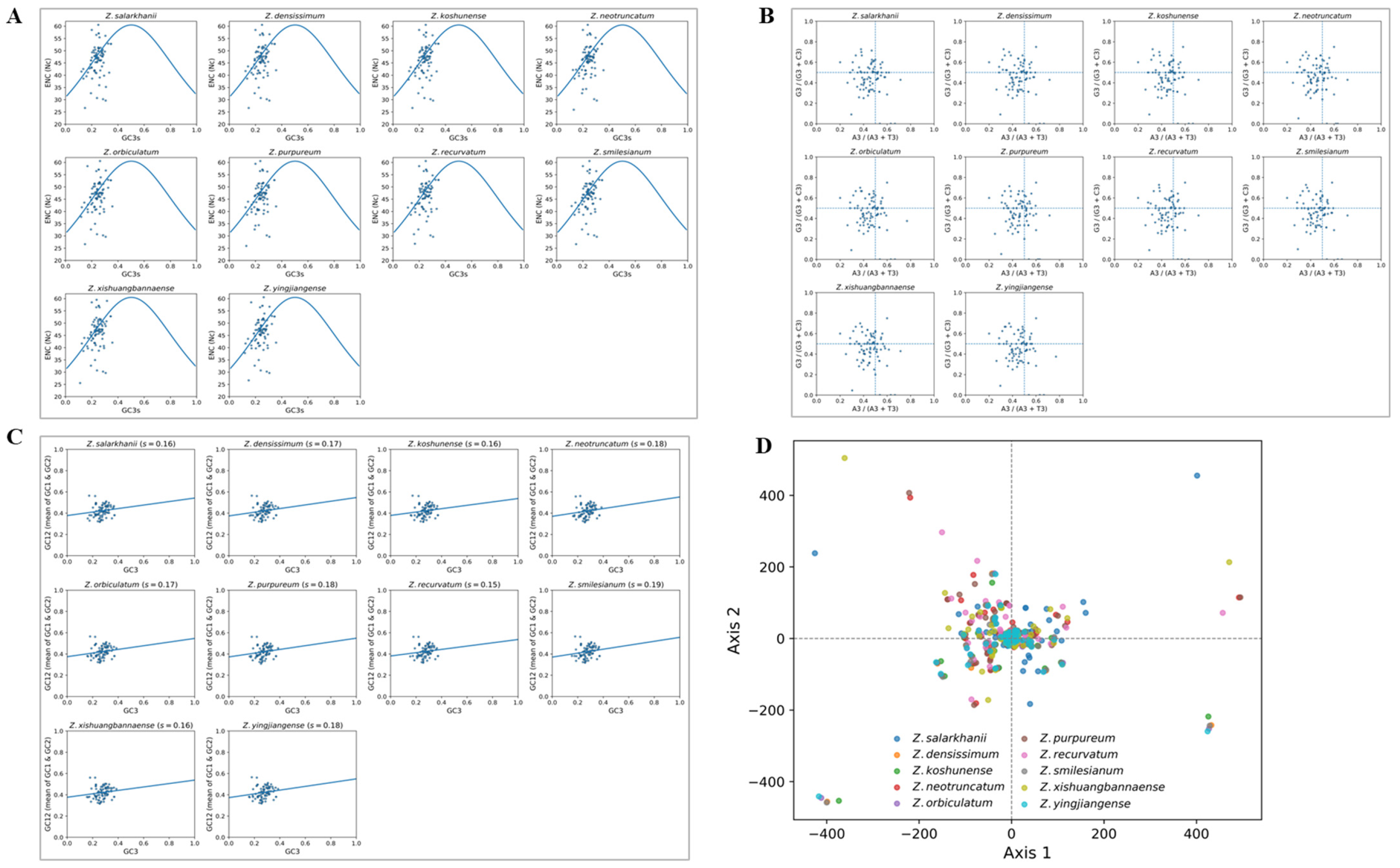

3.2.2. Analysis of Codon Usage Bias and Optimal Codon Patterns

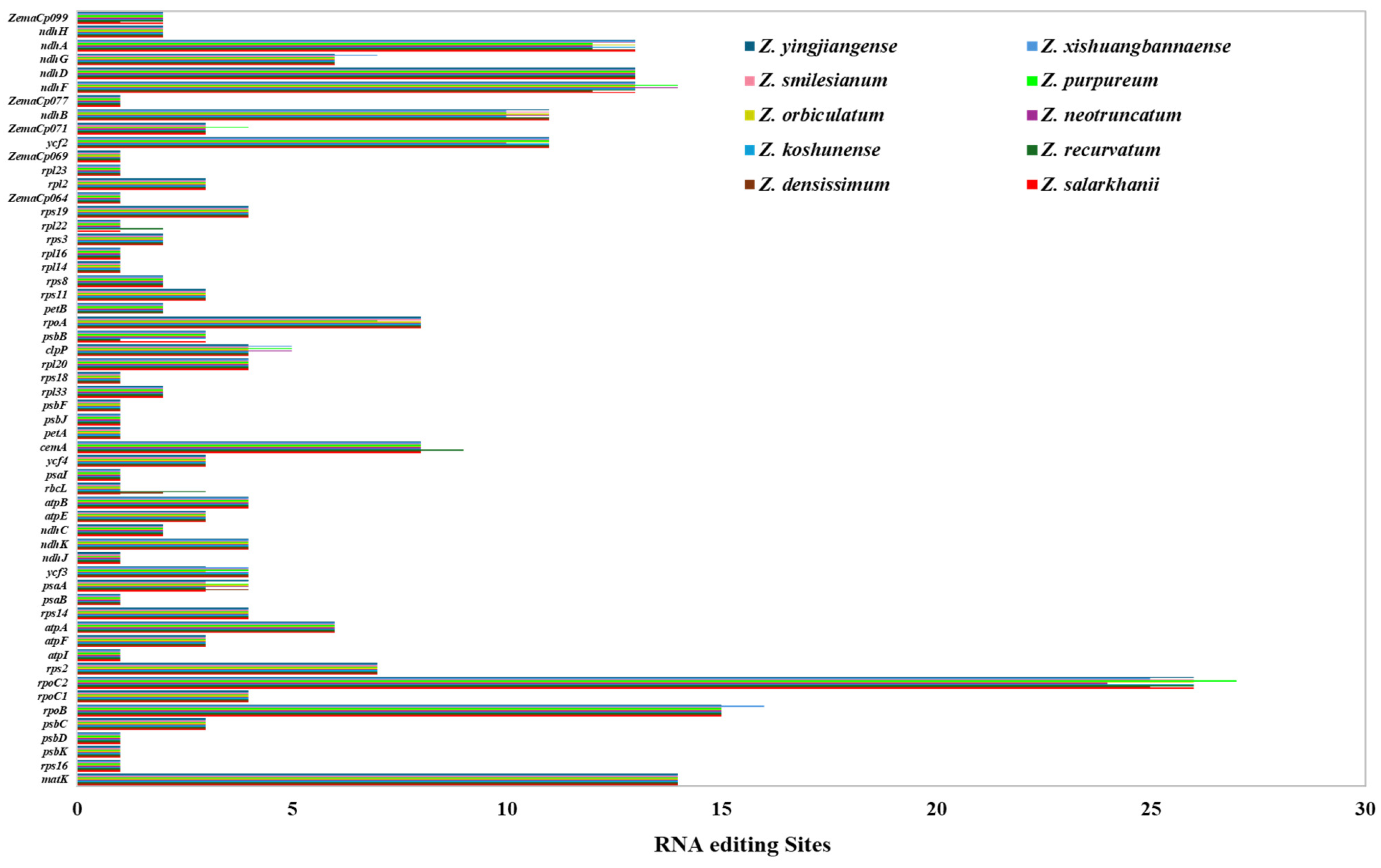

3.2.3. RNA Editing Sites

3.3. SSRs and Long Repeats Analyses

3.4. IR Contraction and Expansion Analyses

3.5. Genomic Comparative and Nucleotide Diversity Analyses

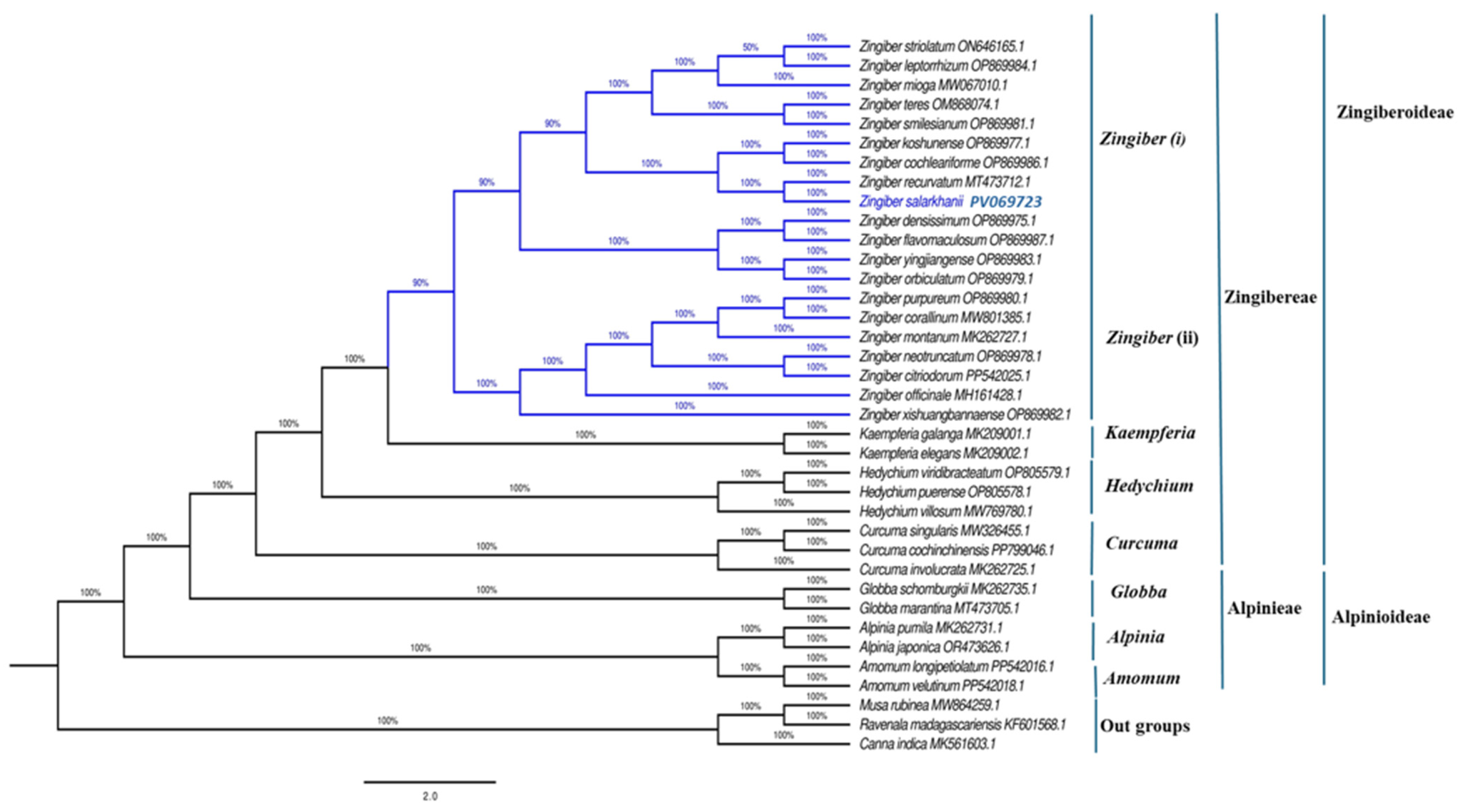

3.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, M.; Yun, X.; Ren, S.; Qing, Z.; Luo, F. Plants of the Genus Zingiber: A Review of Their Ethnomedicine, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology. Molecules 2022, 27, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitpromma, T.; Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P.; Boonma, T. Diversity, Traditional Uses, Economic Values, and Conservation Status of Zingiberaceae in Kalasin Province, Northeastern Thailand. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, B.; Sultana, R.; Saddaf, N. The Effectiveness of Nature-Based Solutions to Address Climate Change in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2024, 10, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Rashid, M.E. Status of Endemic Plants of Bangladesh and Conservation Management Strategies. Int. J. Environ. 2013, 2, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Adhikari-Devkota, A.; Imai, T.; Devkota, H.P. Zerumbone and Kaempferol Derivatives from the Rhizomes of Zingiber Montanum (J. Koenig) Link Ex A. Dietr. from Bangladesh. Separations 2019, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L. Taxonomic Studies on Zingiber (Zingiberaceae) in China VII: The Identity of Z. bambusifolium and a New Subspecies. Phytotaxa 2025, 689, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-M.I.; Ye, Y.-J.; Xu, Y.-C.; Liu, J.-M.; Zhu, G.-F. Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Zingiber montanum and Zingiber zerumbet: Genome Structure, Comparative and Phylogenetic Analyses. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Yusuf, M. Zingiber Salarkhanii (Zingiberaceae), a New Species from Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Plant Taxon. 2013, 20, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim Uddin, S.M.; Ripon, A.; Sultana, N.; Rahman, M. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Screening of Zingiber Salarkhanii Rahman et Yusuf Roots Growing in Bangladesh. Adv. Med. Plant Res. 2022, 10, 39–47. Available online: https://www.netjournals.org/z_AMPR_22_020.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Paudel, K.R.; Orent, J.; Penela, O.G. Pharmacological Properties of Ginger (Zingiber officinale): What Do Meta-Analyses Say? A Systematic Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1619655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Q.Q.; Xu, X.Y.; Cao, S.Y.; Gan, R.Y.; Corke, H.; Beta, T.; Li, H. Bin Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods 2019, 8, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafarzadeh, A.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Nemati, M. Therapeutic Potential of Ginger against COVID-19: Is There Enough Evidence? J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Sci. 2021, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jamal, H.; Idriss, S.; Roufayel, R.; Abi Khattar, Z.; Fajloun, Z.; Sabatier, J.M. Treating COVID-19 with Medicinal Plants: Is It Even Conceivable? A Comprehensive Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Majumder, P.B.; Sen Mandi, S. Species-Specific AFLP Markers for Identification of Zingiber officinale, Z. montanum and Z. zerumbet (Zingiberaceae). Genet. Mol. Res. 2011, 10, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Kress, W.; Prince, L.M.; Williams, K.J. The Phylogeny and a New Classification of the Gingers (Zingiberaceae): Evidence from Molecular Data. Am. J. Bot. 2002, 89, 1682–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhai, X.; He, L.; Wang, Z.; Cao, H.; Wang, P.; Ren, W.; Ma, W. Morphological Description and DNA Barcoding Research of Nine Syringa Species. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1544062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R.; Gunwal, I.; Chauhan, N.; Agrawal, Y. DNA Barcoding for Identification and Detection of Species. Lett. Appl. NanoBioSci 2022, 11, 3542–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Gao, X.F.; Zhang, J.Y.; Jiang, L.S.; Li, X.; Deng, H.N.; Liao, M.; Xu, B. Complete Chloroplast Genomes Provide Insights into Evolution and Phylogeny of Campylotropis (Fabaceae). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 895543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Wang, L.; Lei, J.; Duan, B.; Ma, W.; Xiao, S.; Qi, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shen, X.; et al. A Comparative Analysis of the Chloroplast Genomes of Four Salvia Medicinal Plants. Engineering 2019, 5, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, M.; Reginato, M.; Souza-Chies, T.T.; Majure, L.C. Insights into Chloroplast Genome Evolution Across Opuntioideae (Cactaceae) Reveals Robust Yet Sometimes Conflicting Phylogenetic Topologies. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 538287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Xu, B.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Han, J.; Lei, Y.; Yang, Q.; Peng, F.; Liu, Z.L. Transit from Autotrophism to Heterotrophism: Sequence Variation and Evolution of Chloroplast Genomes in Orobanchaceae Species. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 542017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, B.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Ye, H.; Ma, J. Comparative Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequences of Four Camellia Species. Braz. J. Bot. 2024, 47, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, C.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Ye, J.; Yu, C.; Li, Z.; et al. SOAPnuke: A MapReduce Acceleration-Supported Software for Integrated Quality Control and Preprocessing of High-Throughput Sequencing Data. Gigascience 2018, 7, gix120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.-J.; Yu, W.-B.; Yang, J.-B.; Song, Y.; dePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.-S.; Li, D.-Z. GetOrganelle: A Fast and Versatile Toolkit for Accurate de Novo Assembly of Organelle Genomes. Genome Biol. 2018, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caycho, E.; La Torre, R.; Orjeda, G. Assembly, Annotation and Analysis of the Chloroplast Genome of the Algarrobo Tree Neltuma pallida (Subfamily: Caesalpinioideae). BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillich, M.; Lehwark, P.; Pellizzer, T.; Ulbricht-Jones, E.S.; Fischer, A.; Bock, R.; Greiner, S. GeSeq—Versatile and Accurate Annotation of Organelle Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W6–W11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Wei, J.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, C.; Deng, C.; Zeng, P.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Q. Codon Usage Patterns and Genomic Variation Analysis of Chloroplast Genomes Provides New Insights into the Evolution of Aroideae. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, B.; Uddin, A.; Chakraborty, S. Composition, Codon Usage Pattern, Protein Properties, and Influencing Factors in the Genomes of Members of the Family Anelloviridae. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Nie, L. Comparative Analysis of Codon Usage Bias in Transcriptomes of Eight Species of Formicidae. Genes 2025, 16, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Xiao, W.; Luo, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Chen, X.; He, J.; Sha, A.; Gui, M.; Li, Q. Comprehensive Analysis of Codon Bias in 13 Ganoderma Mitochondrial Genomes. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1170790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Gao, J.; Gai, M.; Pan, Y.; Cao, J.; Peng, T.; Liu, Y.; Yang, K. Comparative Analysis of Codon Usage Bias and Host Adaptation across Avian Metapneumovirus Genotypes. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Liu, S.; Zheng, H.; Li, B.; Qi, Q.; Wei, L.; Zhao, T.; He, J.; Sun, J. Non-Uniqueness of Factors Constraint on the Codon Usage in Bombyx mori. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, S.; He, D.; Liu, J.; He, X.; Lin, C.; Li, J.; Huang, Z.; Huang, L.; Nie, G.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Codon Usage Patterns in the Chloroplast Genomes of Fagopyrum Species. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaundal, R.; Sahu, S.S.; Verma, R.; Weirick, T. Identification and Characterization of Plastid-Type Proteins from Sequence-Attributed Features Using Machine Learning. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xin, C.; Xiao, Q.S.; Lin, Y.T.; Li, L.; Zhao, J.L. Codon Usage Bias in Chloroplast Genes Implicate Adaptive Evolution of Four Ginger Species. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1304264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, Z. Comparative Study on Codon Usage Patterns across Chloroplast Genomes of Eighteen Taraxacum Species. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Su, Y.; Liu, Z.J.; Wang, T. Statistical Genomics Analysis of Simple Sequence Repeats from the Paphiopedilum Malipoense Transcriptome Reveals Control Knob Motifs Modulating Gene Expression. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2304848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, X.; Tian, H.; Qiu, J.; Ma, H.; Tan, D. Complete Chloroplast Genome of Megacarpaea Megalocarpa and Comparative Analysis with Related Species from Brassicaceae. Genes 2024, 15, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, Q.; Xu, L.; Gao, H.; Liu, L.; Zhou, X. CPJSdraw: Analysis and Visualization of Junction Sites of Chloroplast Genomes. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, I.; Kim, W.J.; Yeo, S.M.; Choi, G.; Kang, Y.M.; Piao, R.; Moon, B.C. The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequences of Fritillaria ussuriensis Maxim. and Fritillaria cirrhosa D. Don, and Comparative Analysis with Other Fritillaria Species. Molecules 2017, 22, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Chen, H.; Liu, S. The Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Four Aspidopterys Species and a Comparison with Other Malpighiaceae Species. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Nie, L.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Song, J.; Yao, H. Comparative and Phylogenetic Analyses of the Chloroplast Genomes of Species of Paeoniaceae. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis Version 12 for Adaptive and Green Computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.M.; Li, J.; Wang, D.R.; Xu, Y.C.; Zhu, G.F. Molecular Evolution of Chloroplast Genomes in Subfamily Zingiberoideae (Zingiberaceae). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Cai, X.; Gong, M.; Xia, M.; Xing, H.; Dong, S.; Tian, S.; Li, J.; Lin, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Complete Chloroplast Genomes Provide Insights into Evolution and Phylogeny of Zingiber (Zingiberaceae). BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, N.; Wang, H.; Luo, H.; Xie, Z.; Yu, H.; Chang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zheng, X.; Sheng, J.; et al. Comparative Chloroplast Genomics of Rutaceae: Structural Divergence, Adaptive Evolution, and Phylogenomic Implications. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1675536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathy, S.T.; Udayasuriyan, V.; Bhadana, V. Codon Usage Bias. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 539–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Liang, Y.; Wang, T.; Su, Y. Correlations of Gene Expression, Codon Usage Bias, and Evolutionary Rates of the Mitochondrial Genome Show Tissue Differentiation in Ophioglossum vulgatum. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Li, X.; Chen, T.; Chen, Z.; Jin, Y.; Malik, K.; Li, C. Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Achnatherum inebrians and Comparative Analyses with Related Species from Poaceae. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Alzahrani, D.A.; Albokhari, E.J.; Alawfi, M.S.; Alsubhi, A.I. The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Curcuma Bakerii, an Endemic Medicinal Plant of Bangladesh: Insights into Genome Structure, Comparative Genomics, and Phylogenetic Relationships. Genes 2025, 16, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gong, W.; Li, Y. Comparative Analysis of the Codon Usage Pattern in the Chloroplast Genomes of Gnetales Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, T. Analysis of Codon Usage Bias in Chloroplast Genomes of Dryas octopetala Var. Asiatica (Rosaceae). Genes 2024, 15, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, Q.; Wu, W.; Lin, Q.; Chen, G.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, M.; Fan, S.; Lin, Y. Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of the First Complete Chloroplast Genome of Shizhenia pinguicula (Orchidaceae: Orchideae). Genes 2024, 15, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.M.; Zhao, C.Y.; Liu, X.F. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequences of Kaempferia Galanga and Kaempferia Elegans: Molecular Structures and Comparative Analysis. Molecules 2019, 24, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.M.; Zhu, G.F.; Xu, Y.C.; Ye, Y.J.; Liu, J.M. Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Three Medicinal Alpinia Species: Genome Organization, Comparative Analyses and Phylogenetic Relationships in Family Zingiberaceae. Plants 2020, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Kim, T.S.; Park, Y.J. Rice Chloroplast Genome Variation Architecture and Phylogenetic Dissection in Diverse Oryza Species Assessed by Whole-Genome Resequencing. Rice 2016, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiapella, J.O.; Barfuss, M.H.J.; Xue, Z.Q.; Greimler, J. The Plastid Genome of Deschampsia cespitosa (Poaceae). Molecules 2019, 24, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zuo, Y.; Zhu, X.; Liao, S.; Ma, J. Complete Chloroplast Genomes and Comparative Analysis of Sequences Evolution among Seven Aristolochia (Aristolochiaceae) Medicinal Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Nie, L.; Sun, W.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Song, J.; Yao, H. Comparative and Phylogenetic Analyses of Ginger (Zingiber officinale) in the Family Zingiberaceae Based on the Complete Chloroplast Genome. Plants 2019, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, S.M. Identification of Novel SSR Markers for Predicting the Geographic Origin of Fungus Schizophyllum Commune Fr. Fungal Biol. 2022, 126, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Li, Q.; Hu, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, S. The Complete Amomum Kravanh Chloroplast Genome Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Commelinids. Molecules 2017, 22, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.Y.; Yang, J.X.; Bai, M.Z.; Zhang, G.Q.; Liu, Z.J. The Chloroplast Genome Evolution of Venus Slipper (Paphiopedilum): IR Expansion, SSC Contraction, and Highly Rearranged SSC Regions. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriquez, C.L.; Abdullah; Ahmed, I.; Carlsen, M.M.; Zuluaga, A.; Croat, T.B.; McKain, M.R. Molecular Evolution of Chloroplast Genomes in Monsteroideae (Araceae). Planta 2020, 251, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Shi, L.; Guo, J.; Fu, L.; Du, P.; Huang, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Chloroplast Phylogenomic Analyses Reveal a Maternal Hybridization Event Leading to the Formation of Cultivated Peanuts. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 804568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Amino Acid | Codon | Count | RSCU | RSFC | Amino Acid | Codon | Count | RSCU | RSFC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phe | UUU | 2411 | 1.26 | 0.63 | Tyr | UAU | 1800 | 1.4 | 0.70 |

| UUC | 1425 | 0.74 | 0.37 | UAC | 779 | 0.6 | 0.30 | ||

| Leu | UUA | 1242 | 1.38 | 0.23 | Stop | UAA * | 1350 | 1.32 | 0.63 |

| UUG | 1161 | 1.29 | 0.22 | UAG * | 784 | 0.76 | 0.37 | ||

| CUU | 1066 | 1.19 | 0.20 | His | CAU | 976 | 1.42 | 0.71 | |

| CUC | 640 | 0.71 | 0.12 | CAC | 403 | 0.58 | 0.29 | ||

| CUA | 794 | 0.88 | 0.15 | Gln | CAA | 1077 | 1.42 | 0.71 | |

| CUG | 494 | 0.55 | 0.09 | CAG | 444 | 0.58 | 0.29 | ||

| Iso | AUU | 1937 | 1.19 | 0.40 | Asn | AAU | 2032 | 1.43 | 0.72 |

| AUC | 1142 | 0.7 | 0.23 | AAC | 807 | 0.57 | 0.29 | ||

| AUA | 1804 | 1.11 | 0.37 | Lys | AAA | 2308 | 1.35 | 0.68 | |

| Met | AUG | 1016 | 1 | 1.00 | AAG | 1099 | 0.65 | 0.33 | |

| Val | GUU | 815 | 1.34 | 0.34 | Asp | GAU | 1143 | 1.48 | 0.74 |

| GUC | 408 | 0.67 | 0.17 | GAC | 406 | 0.52 | 0.26 | ||

| GUA | 799 | 1.31 | 0.3275 | Glu | GAA | 1296 | 1.37 | 0.7 | |

| GUG | 414 | 0.68 | 0.17 | GAG | 594 | 0.63 | 0.3 | ||

| Ser | UCU | 1202 | 1.42 | 0.31556 | Cys | UGU | 772 | 1.21 | 0.6 |

| UCC | 1010 | 1.19 | 0.26444 | UGC | 507 | 0.79 | 0.4 | ||

| UCA | 950 | 1.12 | 0.24889 | Stop | UGA * | 945 | 0.92 | 1.0 | |

| UCG | 657 | 0.77 | 0.17111 | Trp | UGG | 730 | 1 | 1.0 | |

| Pro | CCU | 631 | 1.08 | 0.26933 | Arg | CGU | 377 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| CCC | 573 | 0.98 | 0.24439 | CGC | 244 | 0.45 | 0.2 | ||

| CCA | 739 | 1.26 | 0.31421 | CGA | 548 | 1.01 | 0.4 | ||

| CCG | 403 | 0.69 | 0.17207 | CGG | 363 | 0.67 | 0.2 | ||

| Thr | ACU | 778 | 1.22 | 0.305 | Ser | AGU | 752 | 0.89 | 0.2 |

| ACC | 625 | 0.98 | 0.245 | AGC | 520 | 0.61 | 0.1 | ||

| ACA | 752 | 1.18 | 0.295 | Arg | AGA | 1087 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| ACG | 396 | 0.62 | 0.155 | AGG | 634 | 1.17 | 0.3 | ||

| Ala | GCU | 471 | 1.31 | 0.32668 | Gly | GGU | 536 | 0.99 | 0.2 |

| GCC | 330 | 0.92 | 0.22943 | GGC | 321 | 0.59 | 0.1 | ||

| GCA | 441 | 1.23 | 0.30673 | GGA | 801 | 1.48 | 0.4 | ||

| GCG | 197 | 0.55 | 0.13716 | GGG | 502 | 0.93 | 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Islam, M.R.; Alzahrani, D.A.; Albokhari, E.J.; Alawfi, M.S.; Alsubhi, A.I. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of the Endemic and Medicinal Plant Zingiber salarkhanii: Comparative Analysis and Phylogenetic Relationships. Biology 2026, 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010014

Islam MR, Alzahrani DA, Albokhari EJ, Alawfi MS, Alsubhi AI. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of the Endemic and Medicinal Plant Zingiber salarkhanii: Comparative Analysis and Phylogenetic Relationships. Biology. 2026; 15(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleIslam, Mohammad Rashedul, Dhafer A. Alzahrani, Enas J. Albokhari, Mohammad S. Alawfi, and Arwa I. Alsubhi. 2026. "Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of the Endemic and Medicinal Plant Zingiber salarkhanii: Comparative Analysis and Phylogenetic Relationships" Biology 15, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010014

APA StyleIslam, M. R., Alzahrani, D. A., Albokhari, E. J., Alawfi, M. S., & Alsubhi, A. I. (2026). Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of the Endemic and Medicinal Plant Zingiber salarkhanii: Comparative Analysis and Phylogenetic Relationships. Biology, 15(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010014