Methodological Standards for Conducting High-Quality Systematic Reviews

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Formulating the Research Question

- (1)

- In degraded tropical forest ecosystems, does reforestation with native tree species, compared to natural recovery without intervention, lead to greater increases in species richness and abundance of native fauna, based on long-term field observational studies?Population (P): Degraded tropical forest ecosystems, defined as forests with >50% canopy loss, located within the Amazon Basin (including Brazil, Peru, Colombia), based on WWF ecoregion classifications.Intervention (I): Reforestation efforts involving the planting of native tree species, defined as species naturally occurring in the respective ecoregion, excluding exotics and non-native cultivars.Comparator (C): Natural recovery without active planting or management interventions, defined as passive regrowth following disturbance.Outcome (O): Change in species richness (number of native plant and animal species per hectare, measured via standardized biodiversity surveys) and abundance of native fauna (total counts of individuals per species), assessed separately.Timeframe (T): Minimum of 5 years post-intervention to capture long-term ecological recovery trajectories.Study design (S): Prospective or retrospective observational studies with longitudinal monitoring, excluding short-term experiments (<1 year).

- (2)

- In Pseudomonas aeruginosa cultures, does exposure to sub-lethal concentrations of ciprofloxacin, compared to no antibiotic treatment, reduce biofilm formation in in vitro experimental studies?Population (P): Clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa collected from hospitalized adult patients (>18 years) in tertiary care hospitals.Intervention (I): Use of antibiotic A (e.g., ciprofloxacin) administered according to standard dosing guidelines.Comparator (C): Use of antibiotic B (e.g., ceftazidime) or no antibiotic treatment (supportive care only).Outcome (O): Antibiotic resistance development, defined as ≥4-fold increase in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) measured by broth microdilution assays.Timeframe(T): Resistance assessed at baseline and after a minimum treatment period of 7 days.Study design (S): Randomized controlled trials or observational cohort studies with appropriate resistance-testing protocols.

- (3)

- In Arabidopsis thaliana, how does exposure to salicylic acid, compared to untreated controls, influence the expression of pathogen-resistance genes, based on transcriptomic data from time-course experiments?Population (P): Laboratory-grown Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Col-0 plants at the rosette stage (4 weeks post-germination), cultivated under standardized photoperiod and temperature conditions.Intervention (I): Treatment with 1 mM salicylic acid (SA), applied via foliar spray, simulating immune signaling induction.Comparator (C): Untreated control plants sprayed with distilled water under identical conditions.Outcome (O): Differential expression levels of key defense-related genes (e.g., PR1, NPR1, WRKY70) quantified using RNA-seq and normalized counts (TPM/RPKM), with validation by qRT-PCR.Timeframe (T): Gene expression measured at baseline (0 h), 1 h, 6 h, and 24 h post-treatment to capture temporal transcriptional dynamics.Study Design (S): Controlled in vitro experiments with randomized assignment and technical triplicates, using at least two independent biological replicates per time point.

- (4)

- How do adult members of Indigenous communities living adjacent to protected wildlife reserves in the Amazon Basin perceive the social and ecological impacts of community-based conservation programs, as explored through in-depth qualitative interviews? S (Sample): Adult members (≥18 years old) of Indigenous communities residing within 10 km of protected wildlife reserves in Brazil’s Amazon Basin (e.g., Kayapó, Yanomami territories); PI (Phenomenon of Interest): Perceptions and lived experiences related to community-based conservation programs, including views on biodiversity, land use, and cultural autonomy; D (Design): Qualitative studies using semi-structured or in-depth interviews, ethnographic methods, or participatory focus groups; E (Evaluation): Thematic data describing perceived benefits (e.g., increased wildlife), concerns (e.g., reduced hunting access), and trust in conservation agencies; R (Research type): Qualitative studies only (excluding quantitative surveys or mixed-methods designs unless qualitative data are reported separately and in detail).

- (5)

- How do early-career molecular biology researchers perceive the use of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technologies in basic versus translational research contexts, as explored through qualitative interviews? S (Sample): Early-career researchers (PhD students and postdoctoral fellows with ≤5 years of experience) working in molecular biology laboratories across research institutions in the United States and Europe; PI (Phenomenon of Interest): Perceptions, ethical concerns, and decision-making processes related to the use of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in both basic research (e.g., model organism studies) and translational/clinical applications (e.g., gene therapy); D (Design): Qualitative studies using semi-structured interviews, online focus groups, or ethnographic observation in lab settings; E (Evaluation): Thematic data describing perceived benefits (e.g., research acceleration, therapeutic potential), risks (e.g., off-target effects, ethical misuse), and institutional pressures (e.g., funding priorities, publication expectations); R (Research type): Qualitative studies only, excluding mixed-method studies unless the qualitative data are clearly reported and analyzed separately.

3. Developing a Protocol

4. Formulating the Search Strategy

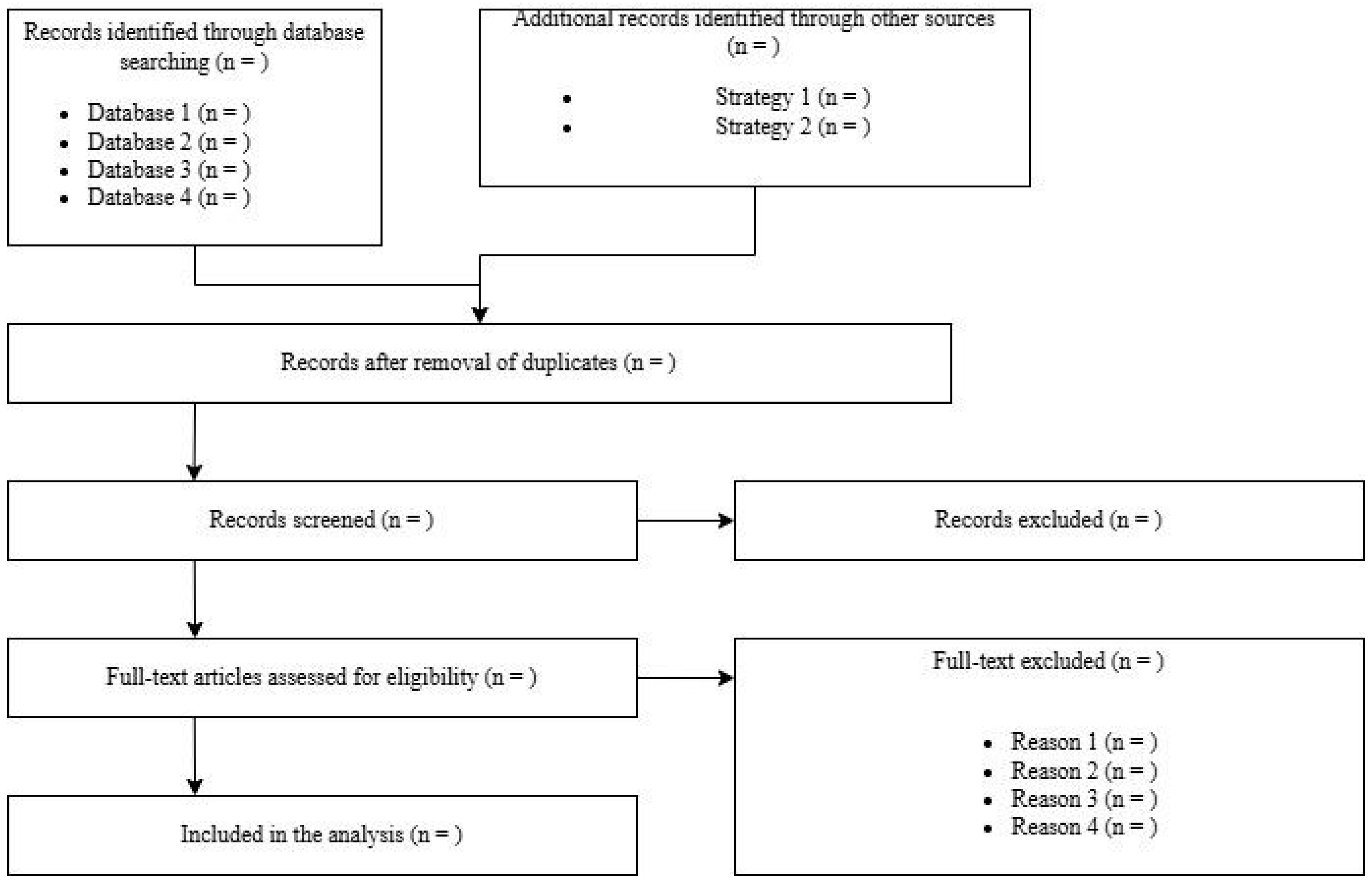

5. Study Screening and Selection

6. Data Extraction

7. Assessing Risk of Bias

- (1)

- Selection bias (e.g., randomization, allocation concealment)

- (2)

- Performance bias (e.g., blinding of participants and personnel)

- (3)

- Detection bias (e.g., blinding of outcome assessors)

- (4)

- Attrition bias (e.g., incomplete outcome data)

- (5)

- Reporting bias (e.g., selective outcome reporting)

8. Data Synthesis–Quantitative Synthesis (Meta-Analysis)

9. Data Synthesis–Qualitative Synthesis (Narrative Synthesis)

10. Assessing Certainty of Evidence

11. Alternative Approaches to Evidence Synthesis

12. Unique Methodological Challenges in Biological Research

- (a)

- Non-standardized outcome measures in ecological and evolutionary studies

- (b)

- Species-specific or strain-specific biological responses

- (c)

- High heterogeneity due to environmental contexts in biodiversity or phylogenetic research

13. Reporting the Systematic Review

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murad, M.H.; Asi, N.; Alsawas, M.; Alahdab, F. New evidence pyramid. BMJ Evid.-Based Med. 2016, 21, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pussegoda, K.; Turner, L.; Garritty, C.; Mayhew, A.; Skidmore, B.; Stevens, A.; Boutron, I.; Sarkis-Onofre, R.; Bjerre, L.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; et al. Systematic review adherence to methodological or reporting quality. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, R.E.; Lagisz, M.; Jennions, M.D.; Koricheva, J.; Noble, D.W.A.; Parker, T.H.; Gurevitch, J.; Page, M.J.; Stewart, G.; Moher, D.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology: A PRISMA Extension. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 1695–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, S. Review of Methodology of Quantitative Reviews Using Meta-Analysis in Ecology. J. Anim. Ecol. 2002, 71, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 6.3; Cochrane: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Mayo, N.E.; Asano, M.; Barbic, S.P. When is a research question not a research question? J. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 45, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, K.S. Formulating the Evidence Based Practice Question: A Review of the Frameworks. Evid. Based Libr. Inf. Pract. 2011, 6, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Clarke, M.; Dooley, G.; Ghersi, D.; Moher, D.; Petticrew, M.; Stewart, L. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: An international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2012, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, A.D.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Nejstgaard, C.H. Adherence to the PRISMA-P 2015 reporting guideline was inadequate in systematic review protocols. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 150, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Forbes, A. Many scenarios exist for selective inclusion and reporting of results in randomized trials and systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 66, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, T.F.; Bruun Nielsen, M.F.; Lindhardt, C.L.; Eriksen, M.B. Using the full PICO model as a search tool for systematic reviews resulted in lower recall for some PICO elements. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 127, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyx, B.; Swaen, G.M.H.; Urlings, M.J.E.; Bouter, L.M.; Zeegers, M.P. The strong focus on positive results in abstracts may cause bias in systematic reviews: A case study on abstract reporting bias. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cassai, A.; Dost, B.; Karapinar, Y.E.; Beldagli, M.; Yalin, M.S.O.; Turunc, E.; Turan, E.I.; Sella, N. Evaluating the utility of large language models in generating search strings for systematic reviews in anesthesiology: A comparative analysis of top-ranked journals. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Gartlehner, G.; Affengruber, L.; Titscher, V.; Noel-Storr, A.; Dooley, G.; Ballarini, N.; König, F. Single-reviewer abstract screening missed 13 percent of relevant studies: A crowd-based, randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 121, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathbone, J.; Hoffmann, T.; Glasziou, P. Faster title and abstract screening? Evaluating Abstrackr, a semi-automated online screening program for systematic reviewers. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan: A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Thomas, J.; Brunton, J.; Graziosi, S. EPPI-Reviewer 4.0: Software for Research Synthesis; EPPI Centre Software: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscemi, N.; Hartling, L.; Vandermeer, B.; Tjosvold, L.; Klassen, T.P. Single data extraction generated more errors than double data extraction in systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2006, 59, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cassai, A.; Boscolo, A.; Zarantonello, F.; Pettenuzzo, T.; Sella, N.; Geraldini, F.; Munari, M.; Navalesi, P. Enhancing study quality assessment: An in-depth review of risk of bias tools for meta-analysis—A comprehensive guide for anesthesiologists. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2023, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadad, A.R.; Moore, R.A.; Carroll, D.; Jenkinson, C.; Reynolds, D.J.; Gavaghan, D.J.; McQuay, H.J. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin. Trials 1996, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Morgan, R.L.; Rooney, A.A.; Taylor, K.W.; Thayer, K.A.; Silva, R.A.; Lemeris, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bateson, T.F.; Berkman, N.D.; et al. A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme UK. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. 2024. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/qualitative-studies-checklist/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo-Olivo, S.; Stiles, C.R.; Hagen, N.A.; Biondo, P.D.; Cummings, G.G. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: Methodological research. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2012, 18, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porritt, K.; Gomersall, J.; Lockwood, C. JBI’s Systematic Reviews: Study selection and critical appraisal. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.; Savović, J.; Higgins, J.P.; Caldwell, D.M.; Reeves, B.C.; Shea, B.; Davies, P.; Kleijnen, J.; Churchill, R.; ROBIS Group. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 69, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Sutton, A.J.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Terrin, N.; Jones, D.R.; Lau, J.; Carpenter, J.; Rücker, G.; Harbord, R.M.; Schmid, C.H.; et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Chu, H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2018, 74, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wong, G.; Westhorp, G.; Pawson, R. Protocol—Realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: Evolving standards (RAMESES). BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lortie, C.J.; Stewart, G.; Rothstein, H.; Lau, J. How to critically read ecological meta-analyses. Res. Synth. Methods 2015, 6, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Macura, B.; Whaley, P.; Pullin, A.S. ROSES RepOrting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses: Pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ. Evid. 2018, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Lagisz, M.; O’Dea, R.E.; Rutkowska, J.; Yang, Y.; Noble, D.W.A.; Senior, A.M. The orchard plot: Cultivating a forest plot for use in ecology, evolution, and beyond. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senior, A.M.; Grueber, C.E.; Kamiya, T.; Lagisz, M.; O’Dwyer, K.; Santos, E.S.; Nakagawa, S. Heterogeneity in ecological and evolutionary meta-analyses: Its magnitude and implications. Ecology 2016, 97, 3293–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G. Meta-analysis in applied ecology. Biol. Lett. 2010, 6, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cassai, A.; Tassone, M.; Geraldini, F.; Sergi, M.; Sella, N.; Boscolo, A.; Munari, M. Explanation of trial sequential analysis: Using a post-hoc analysis of meta-analyses published in Korean Journal of Anesthesiology. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2021, 74, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Risk-of-Bias Tool | Study Type |

|---|---|

| Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) [27] | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| Jadad Scale [28] | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—of Interventions) [29] | Non-Randomized Intervention Studies |

| ROBINS-E (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—of Exposures) [30] | Observational Exposure Studies (Cohort, Case-Control) |

| Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [31] | Cohort and Case-Control Studies |

| QUADAS-2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies) [32] | Diagnostic Accuracy Studies |

| CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) [33] | Qualitative Studies |

| SYRCLE Risk-of-Bias Tool [34] | Animal Intervention Studies |

| AMSTAR 2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) [35] | Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MINORS (Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies) [36] | Non-Randomized Surgical Studies |

| Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool [37] | Public Health Intervention Studies |

| Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools [38] | Various Study Designs |

| ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews) [39] | Systematic Reviews |

| AXIS Tool [40] | Cross-Sectional Studies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Cassai, A.; Dost, B.; Tulgar, S.; Boscolo, A. Methodological Standards for Conducting High-Quality Systematic Reviews. Biology 2025, 14, 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14080973

De Cassai A, Dost B, Tulgar S, Boscolo A. Methodological Standards for Conducting High-Quality Systematic Reviews. Biology. 2025; 14(8):973. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14080973

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Cassai, Alessandro, Burhan Dost, Serkan Tulgar, and Annalisa Boscolo. 2025. "Methodological Standards for Conducting High-Quality Systematic Reviews" Biology 14, no. 8: 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14080973

APA StyleDe Cassai, A., Dost, B., Tulgar, S., & Boscolo, A. (2025). Methodological Standards for Conducting High-Quality Systematic Reviews. Biology, 14(8), 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14080973