Probiotic-Based Cleaning Solutions: From Research Hypothesis to Infection Control Applications

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Identification of Relevant Studies and Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction and Tabulation

2.4. Outcomes of the Included Studies

3. Results

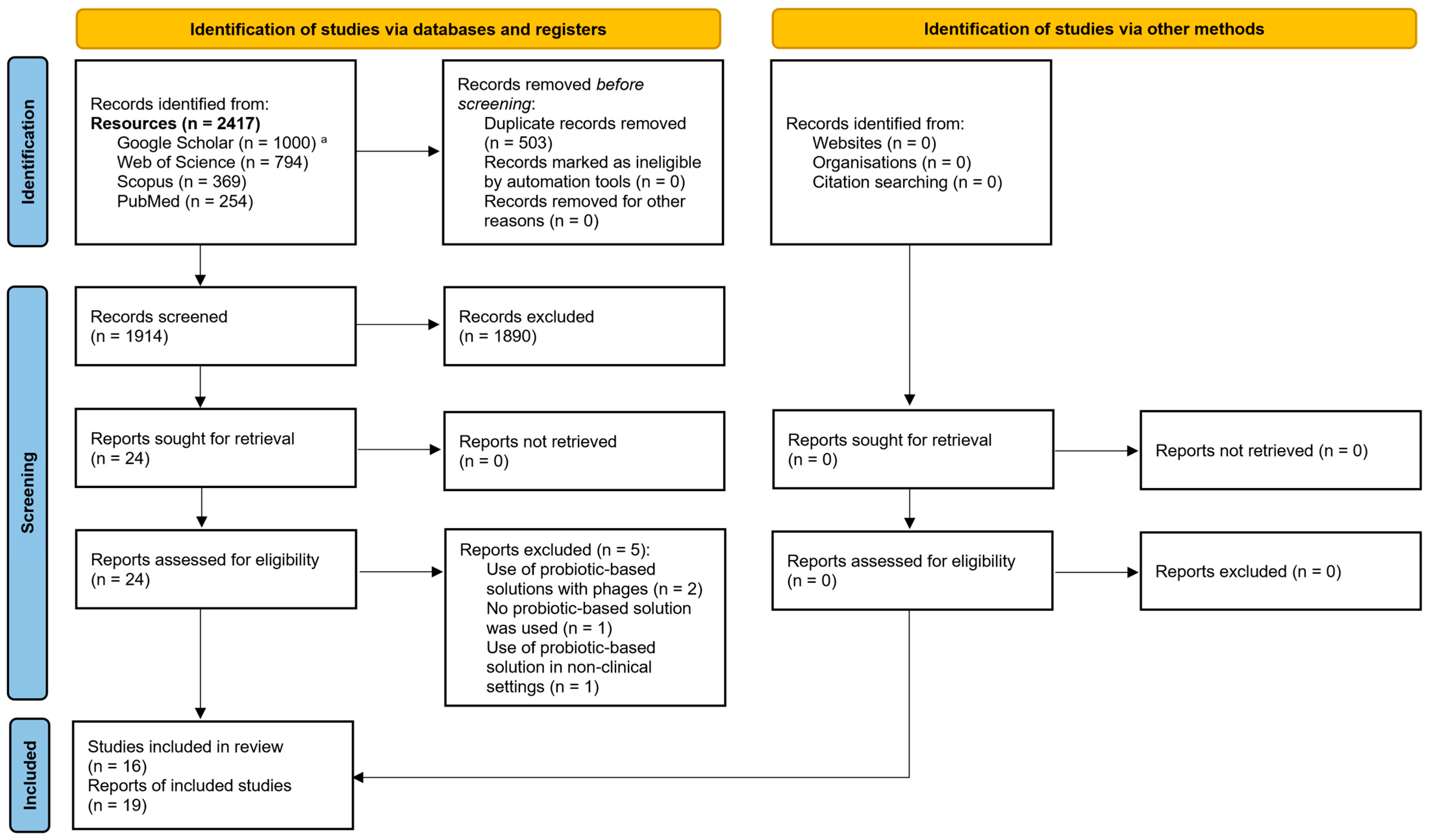

3.1. Identification of Relevant Studies

3.2. Results of the Included Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIMS | Australian Incident Monitoring System |

| ARG | Antimicrobial resistance gene |

| BPR | Biocidal Products Regulation |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CFU | Colony forming unit |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| ECHA | European Chemicals Agency |

| HAI | Healthcare-associated infection |

| HSV-1 | Herpes simplex virus 1 |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MVA | Modified vaccinia virus Ankara |

| PBCS | Probiotic-based cleaning solution |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PDR | Pandrug-resistant |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| UTI | Urinary tract infection |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

References

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.; Sartelli, M.; McKimm, J.; Abu Bakar, M. Health Care-Associated Infections—An Overview. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 2321–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Franceschini, E.; Meschiari, M.; Menozzi, M.; Zona, S.; Venturelli, C.; Digaetano, M.; Rogati, C.; Guaraldi, G.; Paul, M.; et al. Epidemiology and Risk Factors Associated with Mortality in Consecutive Patients with Bacterial Bloodstream Infection: Impact of MDR and XDR Bacteria. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, M.; Sorber, M.; Herzog, A.; Igel, C.; Kugler, C. Technological Innovations in Infection Control: A Rapid Review of the Acceptance of Behavior Monitoring Systems and Their Contribution to the Improvement of Hand Hygiene. Am. J. Infect. Control 2019, 47, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Sifakis, F.; Harbarth, S.; Schrijver, R.; van Mourik, M.; Voss, A.; Sharland, M.; Rajendran, N.B.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Bielicki, J.; et al. Surveillance for Control of Antimicrobial Resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, e99–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Makris, G.C. Probiotic Bacteria and Biosurfactants for Nosocomial Infection Control: A Hypothesis. J. Hosp. Infect. 2009, 71, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhouri, A.; Salloum, A.; Harfouch, R.M. Possible Side Effects of Using Detergents during the Covid19 Pandemic in Syria. Ann. Clin. Cases 2020, 1, 1023. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, N.K.; Ashok, A.; Akondi, B.R. Consequences of Chemical Impact of Disinfectants: Safe Preventive Measures against COVID-19. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2020, 50, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, W.; Tolmay, J.; Tucker, K.; Wolfaardt, G.M. Disinfectant, Soap or Probiotic Cleaning? Surface Microbiome Diversity and Biofilm Competitive Exclusion. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, G.; Russell, A.D. Antiseptics and Disinfectants: Activity, Action, and Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Bayly, A.E. Development of Surfactants and Builders in Detergent Formulations. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2008, 16, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afinogenova, A.G.; Kraeva, L.A.; Afinogenov, G.E.; Veretennikov, V.V. Probiotic-Based Sanitation as Alternatives to Chemical Disinfectants. Russ. J. Infect. Immun. 2018, 7, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Marzooq, F.; Bayat, S.A.; Sayyar, F.; Ishaq, H.; Nasralla, H.; Koutaich, R.; Kawas, S.A. Can Probiotic Cleaning Solutions Replace Chemical Disinfectants in Dental Clinics? Eur. J. Dent. 2018, 12, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caselli, E.; Arnoldo, L.; Rognoni, C.; D’Accolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Lanzoni, L.; Bisi, M.; Volta, A.; Tarricone, R.; Brusaferro, S.; et al. Impact of a Probiotic-Based Hospital Sanitation on Antimicrobial Resistance and HAI-Associated Antimicrobial Consumption and Costs: A Multicenter Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, E.; Berloco, F.; Tognon, L.; Villone, G.; La Fauci, V.; Nola, S.; Antonioli, P.; Coccagna, M.; Balboni, P.; Pelissero, G.; et al. Influence of Sanitizing Methods on Healthcare-Associated Infections Onset: A Multicentre, Randomized, Controlled Pre-Post Interventional Study. J. Clin. Trials 2016, 6, 1000285-1–1000285-6. [Google Scholar]

- Caselli, E.; Brusaferro, S.; Coccagna, M.; Arnoldo, L.; Berloco, F.; Antonioli, P.; Tarricone, R.; Pelissero, G.; Nola, S.; La Fauci, V.; et al. Reducing Healthcare-Associated Infections Incidence by a Probiotic-Based Sanitation System: A Multicentre, Prospective, Intervention Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, E.; D’Accolti, M.; Vandini, A.; Lanzoni, L.; Camerada, M.T.; Coccagna, M.; Branchini, A.; Antonioli, P.; Balboni, P.G.; Di Luca, D.; et al. Impact of a Probiotic-Based Cleaning Intervention on the Microbiota Ecosystem of the Hospital Surfaces: Focus on the Resistome Remodulation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Accolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Bini, F.; Mazziga, E.; Arnoldo, L.; Volta, A.; Bisi, M.; Antonioli, P.; Laurenti, P.; Ricciardi, W.; et al. Potential Use of a Combined Bacteriophage–Probiotic Sanitation System to Control Microbial Contamination and AMR in Healthcare Settings: A Pre-Post Intervention Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Accolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Bonfante, F.; Ricciardi, W.; Mazzacane, S.; Caselli, E. Potential of an Eco-Sustainable Probiotic-Cleaning Formulation in Reducing Infectivity of Enveloped Viruses. Viruses 2021, 13, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauci, V.L. An Innovative Approach to Hospital Sanitization Using Probiotics: In Vitro and Field Trials. J. Microb. Biochem. Technol. 2015, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shuai, W.; Sumner, J.T.; Moghadam, A.A.; Hartmann, E.M. Clinically Relevant Pathogens on Surfaces Display Differences in Survival and Transcriptomic Response in Relation to Probiotic and Traditional Cleaning Strategies. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klassert, T.E.; Zubiria-Barrera, C.; Neubert, R.; Stock, M.; Schneegans, A.; López, M.; Driesch, D.; Zakonsky, G.; Gastmeier, P.; Slevogt, H.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Surface Sanitization Protocols on the Bacterial Community Structures in the Hospital Environment. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleintjes, W.G.; Kotzee, E.P.; Whitelaw, A.; Abrahams, R.; Prag, R.; Ebrahim, M. The Role of Probiotics for Environmental Cleaning in a Burn Unit: A Non-Randomised Controlled Prospective Study. South Afr. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2019, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleintjes, W.G.; Prag, R.; Ebrahim, M.; Kotzee, E.P. The Effect of Probiotics for Environmental Cleaning on Hospital-Acquired Infection in a Burn Centre: The Results of a Non-Randomised Controlled Prospective Study. South Afr. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2020, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leistner, R.; Kohlmorgen, B.; Brodzinski, A.; Schwab, F.; Lemke, E.; Zakonsky, G.; Gastmeier, P. Environmental Cleaning to Prevent Hospital-Acquired Infections on Non-Intensive Care Units: A Pragmatic, Single-Centre, Cluster Randomized Controlled, Crossover Trial Comparing Soap-Based, Disinfection and Probiotic Cleaning. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffritti, I.; D’Accolti, M.; Cason, C.; Lanzoni, L.; Bisi, M.; Volta, A.; Campisciano, G.; Mazzacane, S.; Bini, F.; Mazziga, E.; et al. Introduction of Probiotic-Based Sanitation in the Emergency Ward of a Children’s Hospital During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 1399–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarricone, R.; Rognoni, C.; Arnoldo, L.; Mazzacane, S.; Caselli, E. A Probiotic-Based Sanitation System for the Reduction of Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistances: A Budget Impact Analysis. Pathogens 2020, 9, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandini, A.; Frabetti, A.; Antonioli, P.; Platano, D.; Branchini, A.; Camerada, M.T.; Lanzoni, L.; Balboni, P.; Mazzacane, S. Reduction of the Microbiological Load on Hospital Surfaces through Probiotic-Based Cleaning Procedures: A New Strategy to Control Nosocomial Infections. J. Microbiol. Exp. 2014, 1, 00027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandini, A.; Temmerman, R.; Frabetti, A.; Caselli, E.; Antonioli, P.; Balboni, P.G.; Platano, D.; Branchini, A.; Mazzacane, S. Hard Surface Biocontrol in Hospitals Using Microbial-Based Cleaning Products. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- En 14476:2019; Chemical Disinfectants and Antiseptics—Quantitative Suspension Test for the Evaluation of Virucidal Activity in the Medical Area—Test Method And Requirements (Phase 2/Step 1). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Falagas, M.E.; Rafailidis, P.I.; Makris, G.C. Bacterial Interference for the Prevention and Treatment of Infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2008, 31, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Betsi, G.I.; Athanasiou, S. Probiotics for Prevention of Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezey, E. Interaction between Alcohol and Nutrition in the Pathogenesis of Alcoholic Liver Disease. Semin. Liver Dis. 1991, 11, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shamiri, M.M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, P.; Odhiambo, W.O.; Chen, Y.; Han, B.; Yang, E.; Xun, M.; Han, L.; et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus Species and Their Biosurfactants Eliminate Acinetobacter Baumannii Biofilm in Various Manners. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e04614-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomé, A.R.; Carvalho, F.M.; Teixeira-Santos, R.; Burmølle, M.; Mergulhão, F.J.M.; Gomes, L.C. Use of Probiotics to Control Biofilm Formation in Food Industries. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, M.K.; Abuqwider, J.; Mauriello, G. Anti-Quorum Sensing Activity of Probiotics: The Mechanism and Role in Food and Gut Health. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samonis, G.; Falagas, M.E.; Lionakis, S.; Ntaoukakis, M.; Kofteridis, D.P.; Ntalas, I.; Maraki, S. Saccharomyces Boulardii and Candida Albicans Experimental Colonization of the Murine Gut. Med. Mycol. 2011, 49, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corredor-Rengifo, D.; Tello-Cajiao, M.E.; García-Molina, F.A.; Montero-Riascos, L.F.; Segura-Cheng, J.D. Bacillus Clausii Bacteremia Following Probiotic Use: A Report of Two Cases. Cureus 2024, 16, e57853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Amadoro, C.; Gasperi, M.; Colavita, G. Lactobacilli Infection Case Reports in the Last Three Years and Safety Implications. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikucka, A.; Deptuła, A.; Bogiel, T.; Chmielarczyk, A.; Nurczyńska, E.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Bacteraemia Caused by Probiotic Strains of Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus—Case Studies Highlighting the Need for Careful Thought before Using Microbes for Health Benefits. Pathogens 2022, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, N.W.; Evans, M.R.; Sedivy, J.; Testman, R.; Acedo, K.; Paone, D.; Long, D.; Osimitz, T.G. Safety Assessment of the Use of Bacillus-Based Cleaning Products. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 116, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Korbila, I.P.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E. Probiotics for the Prevention of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2010, 4, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siempos, I.I.; Ntaidou, T.K.; Falagas, M.E. Impact of the Administration of Probiotics on the Incidence of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 38, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Betsi, G.I.; Tokas, T.; Athanasiou, S. Probiotics for Prevention of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women: A Review of the Evidence from Microbiological and Clinical Studies. Drugs 2006, 66, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitsouni, E.; Alexiou, V.; Saridakis, V.; Peppas, G.; Falagas, M.E. Does the Use of Probiotics/Synbiotics Prevent Postoperative Infections in Patients Undergoing Abdominal Surgery? A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 65, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vouloumanou, E.K.; Makris, G.C.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Falagas, M.E. Probiotics for the Prevention of Respiratory Tract Infections: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2009, 34, 197.e1–197.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vliagoftis, H.; Kouranos, V.D.; Betsi, G.I.; Falagas, M.E. Probiotics for the Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008, 101, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsi, G.I.; Papadavid, E.; Falagas, M.E. Probiotics for the Treatment or Prevention of Atopic Dermatitis: A Review of the Evidence from Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2008, 9, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Core Competencies for Infection Control and Hospital Hygiene Professionals in the European Union; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Solna, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes at the National and Acute Health Care Facility Level; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-4-154992-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhar, D.T.; Carrico, R.M.; Cox, K.; de Perio, M.A.; Irwin, K.L.; Lundstrom, T.; Overholt, A.D.; Roberts, K.T.; Russi, M.; Steed, C. Infection Control in Healthcare Personnel: Infrastructure and Routine Practices for Occupational Infection Prevention and Control Services. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/media/pdfs/Guideline-Infection-Control-HCP-H.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on Detergents and Surfactants, Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 648/2004 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52023PC0217 (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Fijan, S.; Kürti, P.; Rozman, U.; Šostar Turk, S. A Critical Assessment of Microbial-Based Antimicrobial Sanitizing of Inanimate Surfaces in Healthcare Settings. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1412269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Accolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Bini, F.; Mazziga, E.; Caselli, E. Tackling Transmission of Infectious Diseases: A Probiotic-based System as a Remedy for the Spread of Pathogenic and Resistant Microbes. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, F.; Soffritti, I.; D’Accolti, M.; Mazziga, E.; Caballero, J.D.; David, S.; Argimon, S.; Aanensen, D.M.; Volta, A.; Bisi, M.; et al. Profiling the Resistome and Virulome of Bacillus Strains Used for Probiotic-Based Sanitation: A Multicenter WGS Analysis. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogacka, A.M.; Saturio, S.; Alvarado-Jasso, G.M.; Salazar, N.; de Los Reyes Gavilán, C.G.; Martínez-Faedo, C.; Suarez, A.; Wang, R.; Miyazawa, K.; Harata, G.; et al. Probiotic-Induced Modulation of Microbiota Composition and Antibiotic Resistance Genes Load, an In Vitro Assessment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montassier, E.; Valdés-Mas, R.; Batard, E.; Zmora, N.; Dori-Bachash, M.; Suez, J.; Elinav, E. Probiotics Impact the Antibiotic Resistance Gene Reservoir along the Human GI Tract in a Person-Specific and Antibiotic-Dependent Manner. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, E.H.-L.; Chen, R.P.-Y.; Dunny, G.M.; Hu, W.-S.; Lee, K.-T. Probiotic Bacillus Affects Enterococcus Faecalis Antibiotic Resistance Transfer by Interfering with Pheromone Signaling Cascades. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e0044221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, M.A.; González, S.N.; Alberto, M.R.; Arena, M.E. Human Probiotic Bacteria Attenuate Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm and Virulence by Quorum-Sensing Inhibition. Biofouling 2020, 36, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Accolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Lanzoni, L.; Bisi, M.; Volta, A.; Mazzacane, S.; Caselli, E. Effective Elimination of Staphylococcal Contamination from Hospital Surfaces by a Bacteriophage–Probiotic Sanitation Strategy: A Monocentric Study. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’ACcolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Piffanelli, M.; Bisi, M.; Mazzacane, S.; Caselli, E. Efficient Removal of Hospital Pathogens from Hard Surfaces by a Combined Use of Bacteriophages and Probiotics: Potential as Sanitizing Agents. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawa, T.; Moriyama, K.; Kinoshita, M. Current Status of Bacteriophage Therapy for Severe Bacterial Infections. J. Intensiv. Care 2024, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Accolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Bini, F.; Mazziga, E.; Cason, C.; Comar, M.; Volta, A.; Bisi, M.; Fumagalli, D.; Mazzacane, S.; et al. Shaping the Subway Microbiome through Probiotic-Based Sanitation during the COVID-19 Emergency: A Pre–Post Case–Control Study. Microbiome 2023, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year [Ref #] | Period of Study, Country | Type of Study | Setting | Tested Surface | PBCS | Duration and/or Design of Probiotic Cleaning | Duration and/or Design of Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afinogrnova, 2018 [14] | NR, Russia | Prospective, comparative interventional | Two rooms in a medical center | Floor | NR | For 1 month | Disinfectants and detergents (not specified) |

| Al-Marzooq, 2018 [15] | 2/2017–5/2017, United Arab Emirates | Prospective, comparative interventional | Three dental clinics | Dentist chair, drainage, handpiece wire, headrest, sides of patient chair, floor, keyboard, spittoon, and sink | Bacillus subtilis | For 3 weeks, daily | For 1 week, daily; floor: chemical solution (sodium lauryl ether sulfate and diethanolamide); other surfaces: disinfectant, (ethanol, 1-propanol, and quaternary ammonium compounds) |

| Caselli, 2016 [19] | NR, Italy | Pre-post interventional | A private hospital | Floor, bed, bathroom sink | Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis (107 spores/mL, 1:100 dilution) | For 6 months | Pre-intervention: conventional cleaning with disinfectants |

| Caselli, 2016 [17]; 2018 [18]; 2019 [16] | 1/2016–6/2016, Italy | Prospective, comparative interventional | Six hospitals (in 1 of 6 hospitals, only conventional cleaning was applied) | Bed, bed footboard, and sink | Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis | For 6 months, daily a | Pre-intervention: for 6 months, conventional cleaning with disinfectants (chlorine-containing products) |

| D’Accolti, 2023 [20] | 3/2021–6/2021, Italy | Pre–post interventional | Two hospitals (H1 and H2) | Room and bathroom surfaces | NR | For 1 month | Pre-intervention: conventional cleaning with chemical-based products |

| Klassert, 2022 [24] | NR, Germany | Prospective, comparative interventional | Neurology ward with nine rooms in a university hospital | Floor, door handle, and sink | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis | For 3 months | Pre-intervention: disinfectants (alcohol, amines, and quaternary ammonium compounds) applied for 3 months, then detergents (non-ionic and anionic surfactants) applied for 3 months |

| Kleintjes, 2019 [25]; 2020 [26] | 8/2017–9/2017, 2/2018 b, South Africa | Prospective, non-randomized, controlled | A burn center (ward and ICU) | NR | Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis | For 10 weeks (8 weeks between August and September 2017 and 2 weeks in February 2018), weekly | Liquid soap detergent, pine liquid disinfectant, and ammonia (NH3) |

| La Fauci, 2015 [22] | 5/2013–7/2013, Italy | Prospective, comparative interventional | Thoracic and vascular surgical wards | Wash basin, floor, desk, bed, bedside table, and door handle | Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis (30 × 106 CFU/mL) with ionic surfactants (0.6%), anionic surfactants (0.8%), and amylases (0.02%) | For 3 months (6 May–30 July) | Chemical-based solutions |

| Leistner, 2023 [27] | 6/2017–8/2018, Germany | Cluster-randomized, controlled, crossover trial | 18 wards (not ICUs, 10 surgical, 8 medical) in a university hospital | Floor, door handle, washbasin, shower cubicle, and toilet surface | Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (5 × 107 CFU/mL, with a total concentration of 1%) | For 4 months (1 month wash-in period before the PBCS application) | For 4 months, consecutive applications of disinfectant (2-phenoxyethanol [10%], 3-aminopropyldodecylamine [8%], benzalkonium chloride [7.5%]); soap-based solutions used as a reference (non-ionic surfactants, anionic surfactants, and fragrances) |

| Soffritti, 2022 [28] | NR, Italy | Pre–post interventional | Emergency rooms of a “Maternal and Child Health Institute” | Floor, bed footboard, and sink | Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis | For 2 months | Pre-intervention: chemical sanitation; also, 0.5% NaOCl was permitted for application in confirmed cases of COVID-19 |

| Tarricone, 2020 [29] | 1/2016–6/2017, Italy | Pre–post interventional | 5 public hospitals (plus a control hospital) | NR | 107 probiotics/mL, 1:100 dilution | Daily for 6 months | Pre-intervention: conventional cleaning solution (NaOCl 0.1%) daily for 6 months |

| Vandini, 2014 [31] | NR, Belgium, Italy | Pre–post interventional | Three hospitals (1 in Belgium, 2 in Italy) | Floor, door, shower, window sill, toilet, sink (made of stone, wood, plastic, glass, metal) | Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis (5 × 107 CFU/mL) | For 6 weeks in 1 Italian hospital and for 24 weeks in 1 Italian and 1 Belgian hospitals | Chemical detergent (in the Belgian hospital), chlorine-based detergent (in Italian hospitals) for 6 weeks in 1 Italian hospital and for 24 weeks in 1 Italian and 1 Belgian hospitals |

| Vandini, 2014 [30] | 3/2011–8/2011, Italy | Prospective, comparative interventional | One university hospital | Corridor, floor, sink | Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis (30 × 106 CFU/mL) with ionic surfactants (0.6%), anionic surfactants (0.8%), and amylases (0.02%) | For 4 months | Chlorine-based solution (0.65% NaOCl, 0.02% surfactants) |

| Author, Year [Ref #] | Presence of Pathogens in PBCS vs. Control | Presence of Bacillus spp. in PBCS vs. Control | Decrease in Resistance Genes | Emergence of HAIs in PBCS vs. Control (n/N [%]) | Reduction in Pathogen CFUs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afinogenova, 2018 [14] | On day 30, no growth of pathogens (Enterobacterales, E. faecium, Staphylococcus spp.) was observed vs. 102 CFU Enterobacterales and 103 CFU Staphylococcus spp. | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Al-Marzooq, 2018 [15] | In the spittoon area, heavy growth was reported for Gram-negative rods and Streptococcus spp. | NA | NA | NA | After PBCS application: Staphylococcus sp., 6.3–87.7; Gram-negative rods, 18.9–84.2; Streptococcus sp., 39.4–100 |

| Caselli, 2016 [17,19] | Up to 98% CFU/m2 decrease in pathogen number | Four months after daily PBCS cleaning, Bacillus quota: 66.0 ± 5.5% vs. 6.7 ± 3.1% | 83/84 (99%) pathogen genes decreased; no acquired resistant genes in Bacillus strains | 6/159 (4) in PBCS (no data for control) | NA |

| Caselli, 2018 [18], Caselli, 2019 [16] | Median CFU/m2 (range ± SD): 4632 (842 ± 12,632) vs. 22,737 (17,053 ± 60,632), p < 0.001 | Bacillus spp. quota, median (range): 69.8 (39.9–86.8) vs. 0 (0–30), p < 0.001 | NA | Cumulative incidence: 128/5531 (2.3) vs. 283/5930 (4.8), range: 1.3–3.7%, p < 0.001; incidence rate ratio (95% CI): 0.45 (0.36–0.45) a | Mean (range): 83 (70–96.3) 79.6 |

| D’Accolti, 2023 [20] | After 2 weeks of daily PBCS application, median CFU/m2 (range), hospital 1 rooms: 3368 (0–87,579) vs. 7158 (0–91,789); hospital 1 bathrooms: 13,264 (0–124,211) vs. 20,211 (421–275,368); hospital 2 rooms: 3158 (0–114,526) vs. 8790 (0–158,900); hospital 2 bathrooms: 6948 vs. 16,420 (0–102,316). After 4 weeks, median CFU/m2 (range), hospital 1 rooms: 2947 (0–60,211) vs. 7158 (0–91,789), p < 0.05; hospital 1 bathrooms: 9895 (0–66,105) vs. 20,211 (421–275,368), p < 0.05 b | Significant increase of Bacillus spp. after PBCS solution: more than 50,000 CFU/m2 in hospital 1, up to 30,000 CFU/m2 in hospital 2 (exact data not reported) | After 4 weeks of daily PBCS application, hospital 1: decrease in all resistance genes; hospital 2: decrease in some genes (ermB, tetB, OXA-23 group, OXA-51 group, spa) c | NA | NA |

| Klassert, 2022 [24] | Decreased intrinsic microbiota in PBCS vs. other cleaning methods (disinfectants and detergents) in all surfaces (floor, door handle, and sink), for the sink: median 16S rRNA copies (IQR), PBCS vs. traditional disinfection: 138.3 (24.38–379.5) vs. 1343 (330.9–9479), p < 0.05 | NA | Mean ± SD, antimicrobial resistance genes/sample, 0.095 ± 0.067 (PBCS) vs. 0.127 ± 0.037 (detergent) vs. 0.386 ± 0.116 (disinfectant), p < 0.01 d | NA | NA |

| Kleintjes, 2019 [25]; 2020 [26] | 24 vs. 12 pathogens, 4 pathogens had an unknown CFU count in the PBCS group; 1–10 CFU(s): 10/20 (50.0) vs. 6/12 (50.0); 11–100 CFUs: 8/20 (40.0) vs. 5/12 (41.7); >100 CFUs: 2/20 (10.0) vs. 1/12 (8.3) | NA | NA | 8/2017–9/2017: 18/64 (28.0) vs. 149/264 (56.4); 2/2018: 4 new HAIs per patient are reported; monthly average difference 58.9% (lower in PBCS); p < 0.005 | NA |

| Fauci, 2015 [22] | E. faecalis and C. albicans: complete elimination after 24 or 48 h of PBCS use; A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae: elimination in the first two months, but in the third month, no significant reduction of bacterial count | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Leistner, 2023 [27] | Overall infection caused by MDR pathogens: 0.862 (0.434–1.710); p = 0.6757 vs. 0.919 (0.468–1.800); p = 0.81 | NA | NA | IRR (95% CI): 0.955 (0.692–1.315); p = 0.84 vs. 0.953 (0.692–1.313); p = 0.83 | NA |

| Soffritti, 2022 [28] | Before PBCS application, median CFU/m2 (95% CI): 26,315 (19,155–52,334); after 2 weeks, median CFU/m2 (95% CI): 6365 (4555–10,201); after 5 weeks, median CFU/m2: 5684; after 9 weeks, median CFU/m2: 41,461 e | Before PBCS application, median CFU/m2: 991; after 2 weeks: 15,418; after 5 weeks: 17,447; after 9 weeks: 13,028 | NA | NA | NA |

| Tarricone, 2020 [29] | NA | NA | NA | 100/106 (94.3) vs. 191/203 (94.1); cumulative HAI incidence: 2.4% vs. 4.6%, OR (95% CI): 0.47 (0.37–0.60); p < 0.001 f | NA |

| Vandini, 2014 [31] | Mean (95% CI) CFU/m2: coliforms: San Giorgio hospital (after 24 weeks) 125 (37–212), p = 0.002; Sant’Anna hospital (after 6 weeks) 764 (340–1188), p < 0.001; AZ Lokeren hospital (after 24 weeks) 3560 (3273–3846), p < 0.001. S. aureus: San Giorgio hospital (after 24 weeks) 286 (87–485), p < 0.001; Sant’Anna hospital (after 6 weeks) 5724 (4139–7309), p < 0.001; AZ Lokeren hospital (after 24 weeks) 627 (395–858), p < 0.001. C. albicans: San Giorgio hospital (after 24 weeks) 78 (0–162), p < 0.001; Sant’Anna hospital (after 6 weeks) 729 (365–1093), p = 0.001. C. difficile: AZ Lokeren hospital (after 24 weeks) 108 (40–177), p = 0.004 g | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Vandini, 2014 [30] | 30 min after application (CFU/100 m2): S. aureus: 49.2 vs. 58.86 (p = 0.014), Coliforms 12.02 vs. 5.00 (p = 0.001), Pseudomonas spp.: 5.53 vs. 1.80 (p = 0.005), Candida spp.: 4.78 vs. 6.08 (p = 0.666); 6.5 h after application: S. aureus: 110.96 vs. 81.65 (p = 0.001), Coliforms 23.05 vs. 3.67 (p = 0.001), Pseudomonas spp.: 9.17 vs. 0.76 (p = 0.001), Candida spp.: 15.02 vs. 4.26 (p = 0.001) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Author, Year [Ref #] | Setting | Tested Surface | Design and Duration of Probiotic Cleaning | PBCS Strain | Design, Duration (Solution) of Control | Presence of Pathogens in PBCS vs. Control | Presence of Bacillus spp. in PBCS vs. Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D’Accolti, 2021 [21] | Suspension and surface tests | For the suspension tests, the “UNI EN 14476:2019” standard procedure was used; for the surface tests, stainless-steel sterile disks were used | According to the European standard procedure “UNI EN 16777:2019”, the antiviral activity of 100 μL of 1:10, 1:50, and 1:100 dilutions of PBCS was evaluated in suspension and surface tests | Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus pumilus, Bacillus subtilis (107 CFU spores/mL) | NA | 24 h after PBCS application: all tested viruses were eliminated with a mean of 0.1 virus titer (log10 TCID50/mL) in all PBCS dilutions (1:10, 1:50, and 1:100) in both suspension (MVA, HSV-1, hCoV-229E, human beta-coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, human H3N2, avian H10N1, swine H1N2) and surface (MVA and hCoV-229E) tests | NA |

| Hu, 2022 [23] | Simulation | Stainless-steel surface simulation of a high-touch surface in a healthcare environment | Probiotic cleaner in ambient and humid conditions | NA | Cleaning solution without probiotics | A. baumannii: maximum 8.75 log10 reduction compared to cleaning solutions without probiotics; K. pneumoniae: maximum 7.42 log10 reduction compared to cleaning solutions without probiotics | Gradually dominating with Bacillus spp. due to the elimination of pathogens |

| Stone, 2020 [11] | Surface tests on blocks with desiccated E. coli and S. aureus | Ceramic, linoleum, and stainless steel (placed indoors and outdoors) | Probotic cleaner (undiluted) twice a week for 8 months | Bacillus spores (8.6 × 107 CFU spores/mL) | Plain soap (saponified vegetable extract, essential oils, natural gum), or disinfectant (3.5% m/v NaOCl) twice a week for 8 months | PBCS and plain soap both limited the survival of S. aureus and E. coli compared to disinfectant and tap water, on all surfaces, both indoors and outdoors | NA |

| Author, Year (Isolates) [Ref #] | Studied Isolate | Antibiotic | Antimicrobial Resistance (n/N%) | Antimicrobial Resistance (n/N%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBCS | Control | ||||

| Al Marzooq, 2018 [15] | S. aureus (50 strains isolated from different surfaces were tested) | Ciprofloxacin | 6/25 (24) | 4/25 (16) | 0.73 |

| Cotrimoxazole | 5/25 (20) | 8/25 (32) | 0.52 | ||

| Cefoxitin | 11/25 (44) | 14/25 (56) | 0.57 | ||

| Ceftriaxone | 10/25 (40) | 10/25 (40) | >0.99 | ||

| Cefpodoxime | 17/25 (68) | 19/25 (76) | 0.75 | ||

| Cefepime | 10/25 (40) | 6/25 (24) | 0.36 | ||

| Meropenem | 7/25 (28) | 4/25 (16) | 0.50 | ||

| Gentamycin | 0/25 (0) | 1/25 (4) | >0.99 | ||

| Al Marzooq, 2018 [15] | Gram-negative rods (40 strains isolated from different surfaces were tested) | Ciprofloxacin | 0/20 (0) | 0/20 (0) | NA |

| Cotrimoxazole | 2/20 (10) | 0/20 (0) | 0.49 | ||

| Cefoxitin | 14/20 (70) | 10/20 (50) | 0.20 | ||

| Ceftriaxone | 7/20 (35) | 5/20 (25) | 0.73 | ||

| Cefpodoxime | 18/20 (90) | 19/20 (95) | >0.99 | ||

| Cefepime | 5/20 (25) | 12/20 (60) | 0.025 | ||

| Meropenem | 0/20 (0) | 0/20 (0) | NA | ||

| Gentamycin | 0/20 (0) | 0/20 (0) | NA | ||

| Caselli, 2019 [16] | S. aureus | Penicillin G | 18/30 (60) | 53/81 (65) | NR |

| Ampicillin | 20/30 (67) | 58/81 (72) | |||

| Vancomycin | 2/30 (7) | 31/81 (38) | |||

| Oxacillin | 18/30 (60) | 50/81 (62) | |||

| Cefotaxime | 22/30 (73) | 61/81 (75) | |||

| Imipenem | 16/30 (53) | 42/81 (52) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Falagas, M.E.; Kontogiannis, D.S.; Sargianou, M.; Falaga, E.M.; Chatzimichali, M.; Michaeloudes, C. Probiotic-Based Cleaning Solutions: From Research Hypothesis to Infection Control Applications. Biology 2025, 14, 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081043

Falagas ME, Kontogiannis DS, Sargianou M, Falaga EM, Chatzimichali M, Michaeloudes C. Probiotic-Based Cleaning Solutions: From Research Hypothesis to Infection Control Applications. Biology. 2025; 14(8):1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081043

Chicago/Turabian StyleFalagas, Matthew E., Dimitrios S. Kontogiannis, Maria Sargianou, Evanthia M. Falaga, Maria Chatzimichali, and Charalambos Michaeloudes. 2025. "Probiotic-Based Cleaning Solutions: From Research Hypothesis to Infection Control Applications" Biology 14, no. 8: 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081043

APA StyleFalagas, M. E., Kontogiannis, D. S., Sargianou, M., Falaga, E. M., Chatzimichali, M., & Michaeloudes, C. (2025). Probiotic-Based Cleaning Solutions: From Research Hypothesis to Infection Control Applications. Biology, 14(8), 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14081043