Hospital-Based Genomic Surveillance of Klebsiella pneumoniae: Trends in Resistance and Infection

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

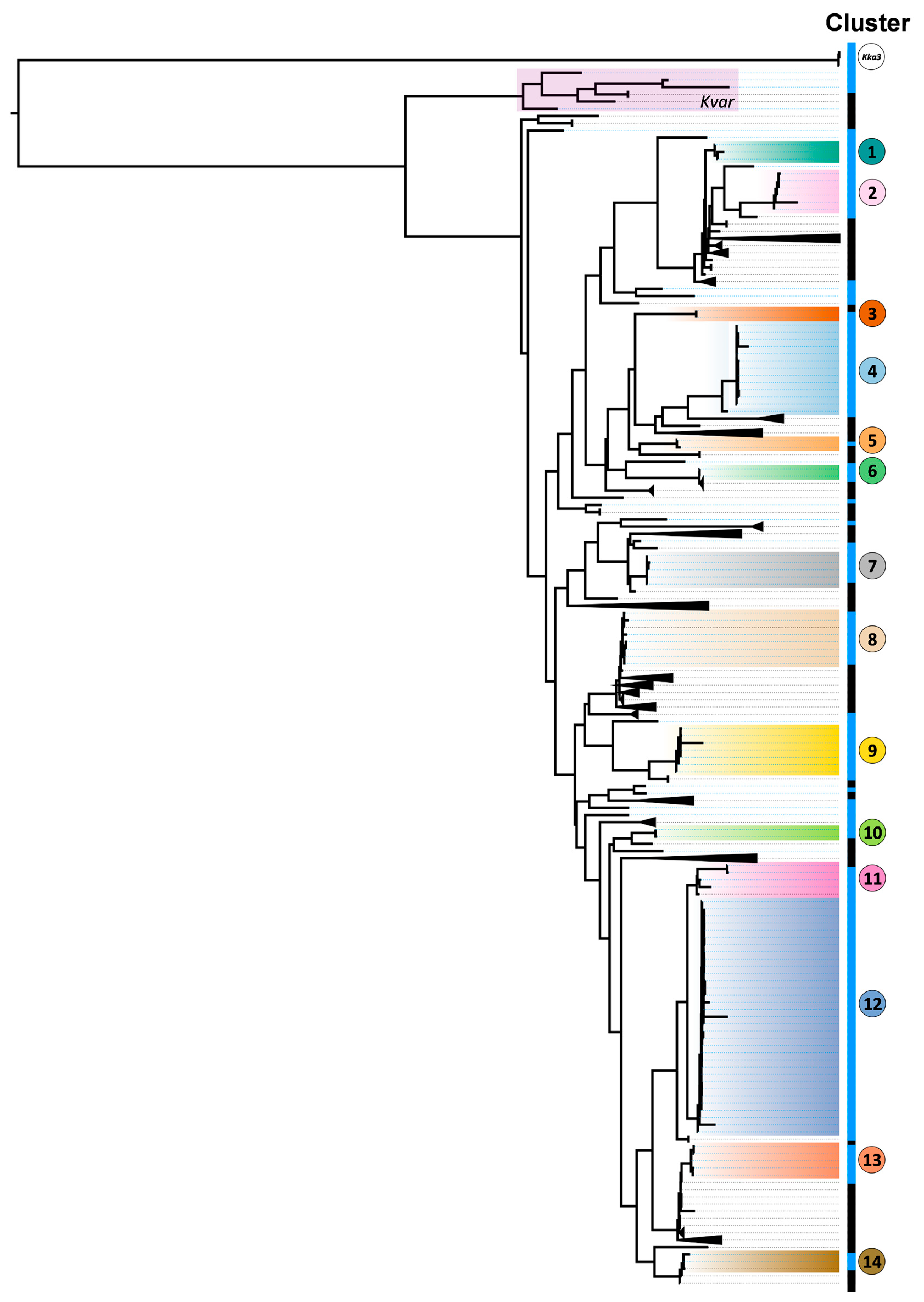

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BV-BRC | Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center |

| CDC | U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CEICVS | Ethics Committee for Research in Life and Health Sciences of the University of Minho |

| CP | Carbapenemase-producing |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| ESBL | Extended-Spectrum Beta-/β-Lactamase |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HB | Hospital de Braga |

| KKa3 | Klebsiella Ka3 |

| Kp | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| KpSC | Kp Species Complex |

| Kvar | Klebsiella variicola subsp. Variicola |

| MLST | Multi-Locus Sequence Typing |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance/resistant |

| PCU | Patient care unit |

| R | Resistance |

| ST | Sequence Type |

| UTI | Urinary Tract Infection |

| V | Virulence |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Aguilar, G.R.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis with Forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K.L.; Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Froumine, R.; Tokolyi, A.; Gorrie, C.L.; Lam, M.M.C.; Duchêne, S.; Jenney, A.; Holt, K.E. Distinct Evolutionary Dynamics of Horizontal Gene Transfer in Drug Resistant and Virulent Clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.M.C.; Wick, R.R.; Watts, S.C.; Cerdeira, L.T.; Wyres, K.L.; Holt, K.E. A Genomic Surveillance Framework and Genotyping Tool for Klebsiella pneumoniae and Its Related Species Complex. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Thomson, N.; Weill, F.-X.; Holt, K.E. Genomic Insights into the Emergence and Spread of Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacterial Pathogens. Science 2018, 360, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales—Third Update, 3 February 2025; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial Resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net)—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention. Surveillance Atlas for Infectious Diseases. Available online: https://atlas.ecdc.europa.eu/public/index.aspx?Dataset=27&HealthTopic=4 (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Spadar, A.; Phelan, J.; Elias, R.; Modesto, A.; Caneiras, C.; Marques, C.; Lito, L.; Pinto, M.; Cavaco-Silva, P.; Ferreira, H.; et al. Genomic Epidemiological Analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae from Portuguese Hospitals Reveals Insights into Circulating Antimicrobial Resistance. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beig, M.; Aghamohammad, S.; Majidzadeh, N.; Asforooshani, M.K.; Rezaie, N.; Abed, S.; Khiavi, E.H.G.; Sholeh, M. Antibiotic Resistance Rates in Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 38, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdigão, J.; Modesto, A.; Pereira, A.L.; Neto, O.; Matos, V.; Godinho, A.; Phelan, J.; Charleston, J.; Spadar, A.; de Sessions, P.F.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing Resolves a Polyclonal Outbreak by Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactam and Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Portuguese Tertiary-Care Hospital. Microb. Genom. 2021, 7, 000349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, A.C.; Novais, Â.; Campos, J.; Rodrigues, C.; Santos, C.; Antunes, P.; Ramos, H.; Peixe, L. Mcr-1 in Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae with Hospitalized Patients, Portugal, 2016–2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caneiras, C.; Lito, L.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Duarte, A. Community-and Hospital-Acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae Urinary Tract Infections in Portugal: Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navon-Venezia, S.; Kondratyeva, K.; Carattoli, A. Klebsiella pneumoniae: A Major Worldwide Source and Shuttle for Antibiotic Resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, S.A.; Cassir, N.; Hamel, M.; Hadjadj, L.; Saidani, N.; Dubourg, G.; Rolain, J.M. Risk Factors for Acquisition of Colistin-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Expansion of a Colistin-Resistant ST307 Epidemic Clone in Hospitals in Marseille, France, 2014 to 2017. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2000022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.A.; Alwashmi, A.S.S.; Abalkhail, A.; Alkahtani, A.M. Emerging Challenges in Klebsiella pneumoniae: Antimicrobial Resistance and Novel Approach. Microb. Pathog. 2025, 202, 107399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martínez, M.; Ruiz Del Castillo, B.; Lecea-Cuello, M.J.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Pascual, Á.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; for the Spanish Network for the Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI) and the Spanish Group for Nosocomial Infections (GEIH). Prevalence of Aminoglycoside-Modifying Enzymes in Escherichia Coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Producing Extended Spectrum β-Lactamases Collected in Two Multicenter Studies in Spain. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczosa, M.K.; Mecsas, J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: Going on the Offense with a Strong Defense. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Li, S.; Li, C.; Yin, Z.; Chen, F.; Hu, L.; Lu, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, G.; et al. The Global Genomic Landscape of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae from 1932 to 2021. mLife 2025, 4, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Su, J.; Xu, X.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Global Emergence of Carbapenem-Resistant Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae Driven by an IncFIIK34 KPC-2 Plasmid. eBioMedicine 2025, 113, 105627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.H.; Arros, P.; Berríos-Pastén, C.; Wijaya, I.; Chu, W.H.W.; Chen, Y.; Cheam, G.; Mohamed Naim, A.N.; Marcoleta, A.E.; Ravikrishnan, A.; et al. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae Employs Genomic Island Encoded Toxins against Bacterial Competitors in the Gut. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcari, G.; Carattoli, A. Global Spread and Evolutionary Convergence of Multidrug-Resistant and Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae High-Risk Clones. Pathog. Glob. Health 2023, 117, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Mazumder, R.; Ahmed, A.; Saima, U.; Phelan, J.E.; Campino, S.; Ahmed, D.; Asadulghani, M.; Clark, T.G.; Mondal, D. Genome Dynamics of High-Risk Resistant and Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae Clones in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1184196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrie, C.L.; Mirčeta, M.; Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Lam, M.M.C.; Gomi, R.; Abbott, I.J.; Thomson, N.R.; Strugnell, R.A.; Pratt, N.F.; et al. Genomic Dissection of Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections in Hospital Patients Reveals Insights into an Opportunistic Pathogen. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promega Corporation. Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit Protocol; Promega: Madison, WI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashin, A.V.; Borodovsky, M. GeneMark.Hmm: New Solutions for Gene Finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.D.; Assaf, R.; Brettin, T.; Conrad, N.; Cucinell, C.; Davis, J.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dickerman, A.; Dietrich, E.M.; Kenyon, R.W.; et al. Introducing the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC): A Resource Combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D678–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center. Comprehensive Genome Analysis (CGA) Service; Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center: Chicago, IL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Duarte, R.; Fernandes, T.; Sousa, M.J.; Sampaio, P.; Rito, T.; Soares, P. Phylogenomics and Functional Annotation of 530 Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Winemaking Environments Reveals Their Fermentome and Flavorome. Stud. Mycol. 2025, 111, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumivero XLSTAT Statistical and Data Analysis Solution. Available online: https://www.xlstat.com (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Song, N.; Chen, Y. Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection: A Meta-Analysis. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 21, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Henriques, I.; Gomila, M.; Manaia, C.M. Common and Distinctive Genomic Features of Klebsiella pneumoniae Thriving in the Natural Environment or in Clinical Settings. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, R.; Spadar, A.; Hendrickx, A.P.A.; Bonnin, R.A.; Dortet, L.; Pinto, M.; Phelan, J.E.; Portugal, I.; Campino, S.; Da Silva, G.J.; et al. Emergence of KPC-3- and OXA-181-Producing ST13 and ST17 Klebsiella pneumoniae in Portugal: Genomic Insights on National and International Dissemination. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyres, K.L.; Lam, M.M.C.; Holt, K.E. Population Genomics of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, T.; Harada, S.; Saito, H.; Tanii, R.; Komori, K.; Kurosawa, M.; Wakatake, H.; Kanazawa, M.; Ohki, U.; Minoura, A.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Klebsiella Variicola Bloodstream Infection Compared with Infection with Other Klebsiella Pneumoniae Species Complex Strains. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0301724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, L.; Foxman, B.; Bradley, S.; McNamara, S.; Lansing, B.; Gibson, K.; Cassone, M.; Armbruster, C.; Mantey, J.; Min, L. Longitudinal Assessment of Multidrug-Resistant Organisms in Newly Admitted Nursing Facility Patients: Implications for an Evolving Population. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vubil, D.; Figueiredo, R.; Reis, T.; Canha, C.; Boaventura, L.; Silva, G.J.D. Outbreak of KPC-3-Producing ST15 and ST348 Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Portuguese Hospital. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, R.; Spadar, A.; Phelan, J.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Lito, L.; Pinto, M.; Gonçalves, L.; Campino, S.; Clark, T.G.; Duarte, A.; et al. A Phylogenomic Approach for the Analysis of Colistin Resistance-Associated Genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae, Its Mutational Diversity and Implications for Phenotypic Resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2022, 59, 106581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccirilli, A.; Cherubini, S.; Azzini, A.M.; Tacconelli, E.; Lo Cascio, G.; Maccacaro, L.; Bazaj, A.; Naso, L.; Amicosante, G.; Perilli, M. Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) of Carbapenem-Resistant K. Pneumoniae Iso-lated in Long-Term Care Facilities in the Northern Italian Region. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, F. Molecular Epidemiology and Drug Resistant Mech-anism of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Elderly Patients with Lower Respiratory Tract In-fection. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 669173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, A.S.; Touret, T.; Faria, N.A.; Ladeiro, S.P.; Costa, J.; Bispo, S.; Serrano, M.; Palos, C.; Miragaia, M.; Leite, R.B.; et al. Using Whole Genome Sequencing to Investigate a Mock-Outbreak of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Real-Time. Acta Médica Port. 2022, 35, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.M.; Cao, J.; Brisse, S.; Passet, V.; Wu, W.; Zhao, L.; Malani, P.N.; Rao, K.; Bachman, M.A. Molecular Epidemiology of Colonizing and Infecting Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. mSphere 2016, 1, e00261-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrie, C.L.; Eta, M.M.; Wick, R.R.; Edwards, D.J.; Thomson, N.R.; Strugnell, R.A.; Pratt, N.F.; Garlick, J.S.; Watson, K.M.; Pilcher, D.V.; et al. Gastrointestinal Carriage Is a Major Reservoir of Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection in Intensive Care Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podschun, R.; Ullmann, U. Klebsiella Spp. as Nosocomial Pathogens: Epidemiology, Taxonomy, Typing Methods, and Pathogenicity Factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, R.; Castro, J.; Silva, S.; Oliveira, H.; Saavedra, M.J.; Azevedo, N.F.; Almeida, C. Exploring the Antibiotic Resistance Profile of Clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates in Portugal. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.J.; Lai, C.C.; Chao, C.M. Changing Epidemiology of Respiratory Tract Infection during COVID-19 Pandemic. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.R.; Guiomar, R.G.; Verdasca, N.; Melo, A.; Rodrigues, A.P. Rede Portuguesa de Laboratórios para o Diagnóstico da Gripe Resurgence of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Children: An Out-of-Season Epidemic in Portugal. Acta Med. Port. 2023, 36, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, N.; Costa, M.I.; Gomes, J.; Sucena, M. Reduction of Severe Exacerbations of COPD during COVID-19 Pandemic in Portugal: A Protective Role of Face Masks? COPD 2021, 18, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cireșă, A.; Tălăpan, D.; Vasile, C.-C.; Popescu, C.; Popescu, G.-A. Evolution of Antimicrobial Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae over 3 Years (2019–2021) in a Tertiary Hospital in Bucharest, Romania. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, O.; Gaio, R.; Carvalho, C.; Correia-Neves, M.; Duarte, R.; Rito, T. A Nationwide Study of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Portugal 2014-2017 Using Epidemiological and Molecular Clustering Analyses. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, H.; Ma, R.; Wu, Y.; Lun, H.; Wang, A.; He, K.; Yu, J.; He, P. A Novel Depolymerase Specifically Degrades the K62-Type Capsular Polysaccharide of Klebsiella pneumoniae. One Health Adv. 2024, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Reuter, S.; Harris, S.R.; Glasner, C.; Feltwell, T.; Argimon, S.; Abudahab, K.; Goater, R.; Giani, T.; Errico, G.; et al. Epidemic of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe Is Driven by Nosocomial Spread. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Sharma, L.; Dela Cruz, C.S.; Zhang, D. Clinical Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Control Strategies of Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 750662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennart, M.; Guglielmini, J.; Bridel, S.; Maiden, M.C.J.; Jolley, K.A.; Criscuolo, A.; Brisse, S. A Dual Barcoding Approach to Bacterial Strain Nomenclature: Genomic Taxonomy of Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2022, 39, msac135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient Characterisation | Patients (n = 101) | Female (n = 40) | Male (n = 61) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Young age (18–44 years old) | 8 | 4 | 4 | |

| Middle age (45–64 years old) | 28 | 6 | 22 | ||

| Old age (over 65 years old) | 65 | 30 | 35 | ||

| Type of Klebsiella sp. Infection | Nosocomial | 87 | 34 | 53 | |

| Community-acquired | 14 | 6 | 8 | ||

| Lifestyle | Tobacco use * | Active smokers | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Past smokers | 15 | 0 | 15 | ||

| Non-smokers | 64 | 29 | 35 | ||

| Alcohol intake * | Alcohol-dependent | 10 | 0 | 10 | |

| Former drinker | 13 | 0 | 13 | ||

| Non/occasional drinker | 60 | 28 | 32 | ||

| Type of residence | Own residence | 81 | 29 | 52 | |

| Family residence | 16 | 9 | 7 | ||

| Nursing home | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Foster family | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Comorbidities | Chronic lung diseases (e.g., COPD, asthma) * | Yes | 13 | 4 | 9 |

| No | 84 | 34 | 50 | ||

| Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases | Diabetes mellitus | 39 | 11 | 28 | |

| Hypertension | 63 | 24 | 39 | ||

| Dyslipidaemia | 53 | 22 | 31 | ||

| Comorbidities overall | Yes | 84 | 32 | 52 | |

| No | 17 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Medical history | Hospital admissions in the last year * | Yes | 43 | 18 | 25 |

| No | 57 | 21 | 36 | ||

| Hospital admissions in the last 3 months * | Yes | 32 | 11 | 21 | |

| No | 68 | 28 | 40 | ||

| Antibiotic treatment in the last year * | Yes | 37 | 15 | 22 | |

| No | 16 | 3 | 13 | ||

| Bacterial infections in the last year | Yes | 34 | 14 | 20 | |

| No | 67 | 25 | 41 | ||

| Death during hospitalisation | Yes | 7 | 2 | 5 | |

| No | 94 | 38 | 56 | ||

| Kp Isolates Classification | Origin of Isolate | Isolates (n = 115) | % | Female (n = 49) | Male (n = 66) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection | Urinary Tract | 33 | 28.70 | 13 | 20 |

| Abdomen | 9 | 7.83 | 3 | 6 | |

| Skin and Soft Tissues | 7 | 6.09 | 2 | 5 | |

| Bacteraemia | 5 | 4.35 | 4 | 1 | |

| Bone | 4 | 3.48 | 3 | 1 | |

| Respiratory System | 3 | 2.61 | 0 | 3 | |

| Overall | 61 | 53.04 | 25 | 36 | |

| Colonisation | Intestinal (CP) | 33 | 28.70 | 14 | 19 |

| Urinary Tract | 16 | 13.91 | 9 | 7 | |

| Respiratory System | 2 | 1.74 | 0 | 2 | |

| Lymphatic System | 1 | 0.87 | 0 | 1 | |

| Overall | 52 | 45.22 | 23 | 29 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 1.74 | 1 | 1 |

| Cluster (n) | MLST | V Score | Virulence loci | R Score | Resistance Determinants | Site of Isolate Collection | Nature of Infection | Isolates Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 3) | ST 15 | 0 | KL112, O1/O2v1, wzi93 | 1 | aac(6’)-Ib-cr, qnrB1, mphA, catA1, sul1, dfrA14, OXA-1, blaCTX-M-15, blaSHV-28, gyrA-83F, GyrA-87A, parC-80I | Urinary tract|3 | Nosocomial|3 | Colonisation|3 |

| 2 (n = 6) | 0 1 | KL23, O1/O2v2 | 1 | aac(3)-IIa, aac(6’)-Ib-cr, aadA16, catA1, arr-3, sul1, dfrA27, OXA-1, blaTEM-1D, blaCTX-M-15, blaSHV-28, gyrA-83F, gyrA-87A, parC-80I | Urinary tract|4 CVC|1 Not attributed|1 | Nosocomial|6 | Infection|4 Colonisation|1 Unknown|1 | |

| 3 (n = 2) | ST 2623 | 0 | KL52, OL103 | 0 | sul2, blaSHV-1 | Urinary tract|1 Other|1 | Nosocomial|2 | Colonisation|2 |

| 4 (n = 13) | ST 13 | 1 2 | KL57, O1/O2v2, ybt+ *, ybt+, clb+ | 1 2 | aac(3)-IIa, aac(6’)-Ib-cr, aadA2, strA, strB, qnrS1, mphA, sul1, sul2, tet(A) *, dfrA12, dfrA14 *, OXA-1, blaTEM-1D, blaCTX-M-15, blaKPC-3 *, blaSHV-1 | Urinary tract|4 Bone|1 Other|8 | Nosocomial|11 Community-acquired|2 | Infection|2 Colonisation|11 |

| 5 (n = 2) | ST 35 | 1 | KL22, O1/O2v1, wzi37, ybt+ | 0 1 | - | Urinary tract|1 Skin/Soft tissue|1 | Nosocomial|2 | Infection|2 |

| 6 (n = 2) | ST 405 | 1 | KL151, O4, wzi143, ybt+ | 1 | aac(3)-IIa, aac(6’)-Ib-cr, strA, strB, qnrB1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA14, OXA-1, blaTEM-1D, blaCTX-M-15, blaSHV-76 | Resp. system|1 Skin/Soft tissue|1 | Nosocomial|2 | Infection|2 |

| 7 (n = 5) | ST 20 | 0 | KL39, O1/O2v1, wzi160 | 1 | aac(3)-IIa, aac(6’)-Ib-cr, strA, strB, qnrB1, sul2, dfrA14, OXA-1, blaTEM-1D, blaCTX-M-15, blaSHV-187 | Urinary tract|2 Resp. system|1 Other|2 | Nosocomial|4 Community-acquired|1 | Infection|3 Colonisation|2 |

| 8 (n = 7) | ST 147 | 0 1 | KL64, O1/O2v1, wzi64, ybt+ * | 0 2 | blaSHV-11, 35Q, blaKPC-3 *, gyrA-83I, parC-80I | Urinary tract|3 Resp. system|1 Other|3 | Nosocomial|7 | Infection|2 Colonisation|5 |

| 9 (n = 7) | ST 29 | 1 | KL19, O1/O2v2, wzi19, ybt+ | 1 | aac(3)-IIa, aac(6’)-Ib-cr, strA, dfrA14, blaCTX-M-15 | Urinary tract|4 Skin/Soft tissue|1 Bone|1 Abdomen|1 | Nosocomial|6 Community-acquired|1 | Infection|5 Colonisation|2 |

| 10 (n = 2) | ST 37 | 1 | KL38, O3b, wzi96, ybt+ | 0 | blaSHV-11, 35Q, blaKPC-3 *, gyrA-83I, parC-80I, | Urinary tract|2 | Nosocomial|2 | Infection|2 |

| 11 (n = 4) | ST 45 | 0 1 | KL24, O1/O2v1, wzi101, ybt+ ** | 0 1 | strA, strB, sul2, blaTEM-1D | Urinary tract|3 Resp. system|1 | Nosocomial|2 Community-acquired|2 | Infection|3 Colonisation|1 |

| 12 (n = 33) | 1 | KL62, O1/O2v1, wzi149, ybt+ | 0 2 | tet(D) *, blaKPC-3 ** | Urinary tract|10 Abdomen|1 Bacteraemia|1 Skin/Soft tissue|1 Other|16 | Nosocomial|32 Community-acquired|1 | Infection|11 Colonisation|21 Unknown|1 | |

| 13 (n = 5) | ST 307 | 0 | KL102, O1/O2v2, wzi173 | 0 1 | aac(6’)-Ib-cr, aadA16, qnrB6, catII.2 *, arr-3, sul1, sul2 *, dfrA27, blaTEM-1D *, blaCTX-M-15 *, blaSHV-28, OmpK35, gyrA-83I, parC -80I | Urinary tract|5 | Nosocomial|4 Community-acquired|1 | Infection|4 Colonisation|1 |

| 14 (n = 2) | ST 348 | 1 | KL62, O1/O2v1, wzi94 *, ybt+ | 1 2 | aac(3)-IIa, strA, strB, qnrB1, sul2, dfrA14, blaTEM-1D, blaCTX-M-15, blaSHV-11, 35Q | Urinary tract|1 Skin/Soft tissue|1 | Nosocomial|1 Community-acquired|1 | Infection|2 |

| Kka3 (n = 3) | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | Bacteraemia|1 Bone|1 Other|1 | Nosocomial|3 | Infection|2 Colonisation|1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olund-Matos, E.; Franco-Duarte, R.; Santa-Cruz, A.; Nogueira, M.; Correia-Neves, M.; Lopes, D.; Silva, R.J.; Araújo, M.R.; Araújo, I.M.; Martins, A.F.; et al. Hospital-Based Genomic Surveillance of Klebsiella pneumoniae: Trends in Resistance and Infection. Biology 2025, 14, 1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121795

Olund-Matos E, Franco-Duarte R, Santa-Cruz A, Nogueira M, Correia-Neves M, Lopes D, Silva RJ, Araújo MR, Araújo IM, Martins AF, et al. Hospital-Based Genomic Surveillance of Klebsiella pneumoniae: Trends in Resistance and Infection. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121795

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlund-Matos, Erica, Ricardo Franco-Duarte, André Santa-Cruz, Maria Nogueira, Margarida Correia-Neves, Diana Lopes, Rui Jorge Silva, Margarida Ribeiro Araújo, Inês Monteiro Araújo, Ana Filipa Martins, and et al. 2025. "Hospital-Based Genomic Surveillance of Klebsiella pneumoniae: Trends in Resistance and Infection" Biology 14, no. 12: 1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121795

APA StyleOlund-Matos, E., Franco-Duarte, R., Santa-Cruz, A., Nogueira, M., Correia-Neves, M., Lopes, D., Silva, R. J., Araújo, M. R., Araújo, I. M., Martins, A. F., Nogueira, C. M., Faustino, A., Cunha, P. G., Soares, P., & Rito, T. (2025). Hospital-Based Genomic Surveillance of Klebsiella pneumoniae: Trends in Resistance and Infection. Biology, 14(12), 1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121795