Targeted NanoBiT Screening Identifies a Novel Interaction Between SNAPIN and Influenza A Virus M1 Protein

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells, Eggs, and Viruses

2.2. Construction of Plasmids

2.3. Antibodies

2.4. Confocal Microscopy

2.5. NanoBiT Luciferase Complementation Experiment

2.6. Protein Interaction Prediction

2.7. Co-Immunoprecipitation Experiment (Co-IP)

2.8. Cell Infection

2.9. GST Pull-Down

3. Results

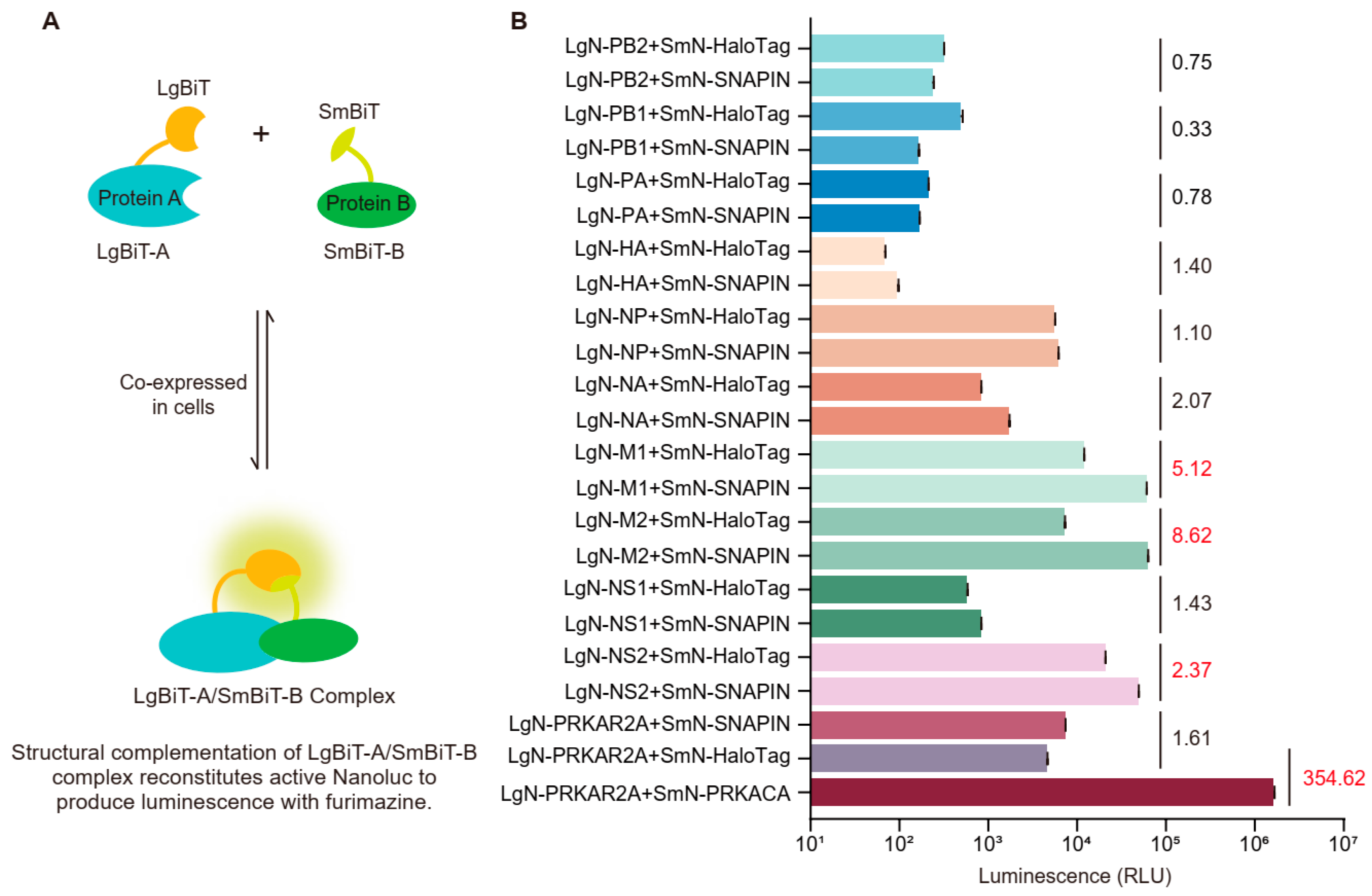

3.1. NanoBiT Screening of SNAPIN–IAV Protein Interactions

3.2. Structural Prediction of PPI

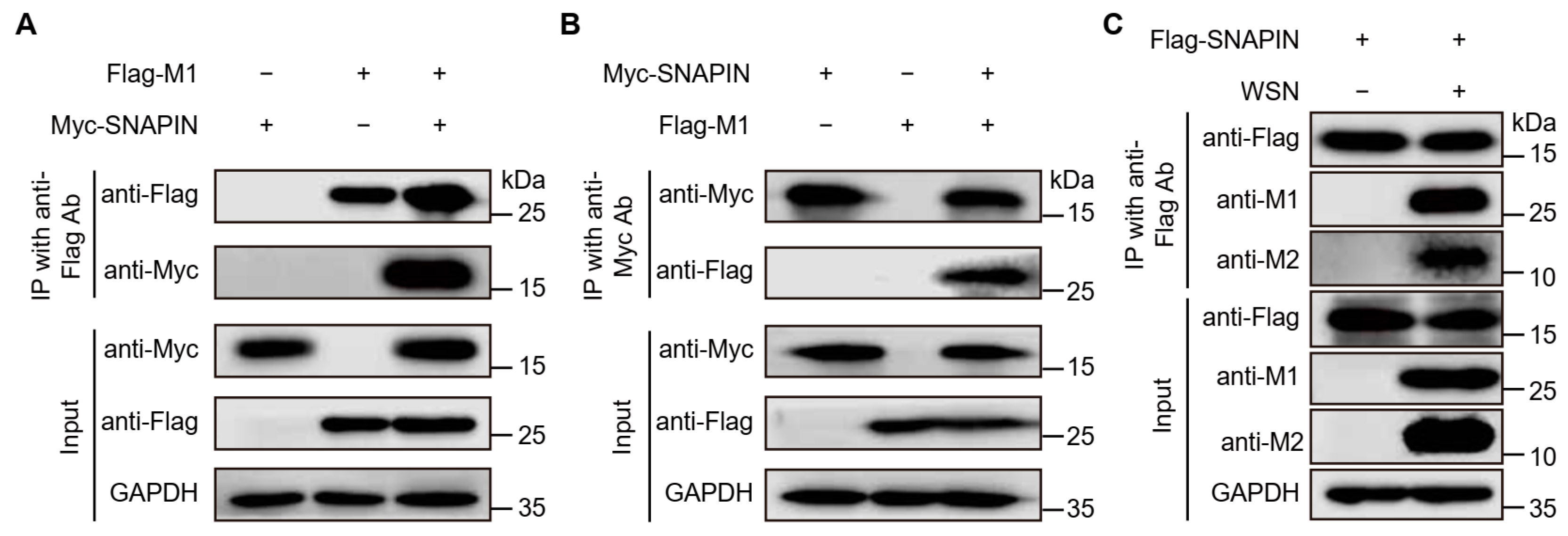

3.3. Co-IP Assays

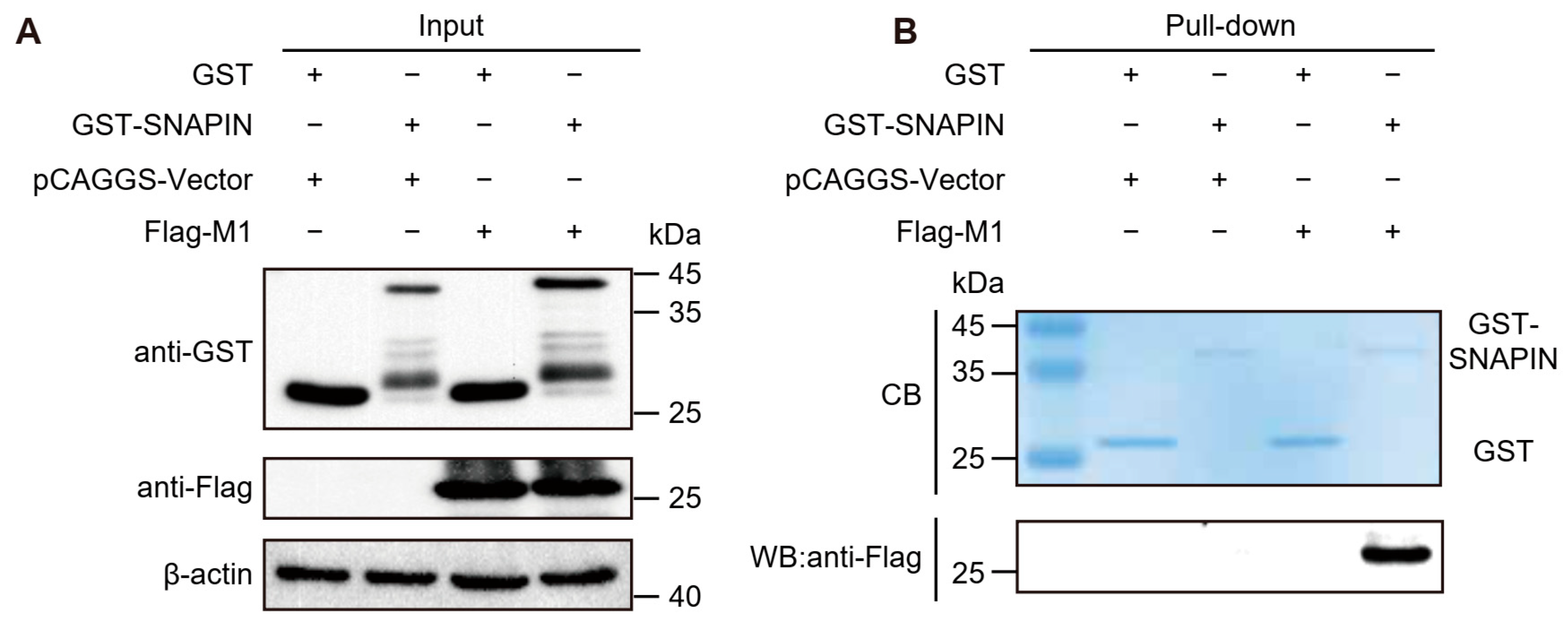

3.4. Detection of SNAPIN–M1 Interaction by GST Pull-Down

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sparrow, E.; Wood, J.G.; Chadwick, C.; Newall, A.T.; Torvaldsen, S.; Moen, A.; Torelli, G. Global production capacity of seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccines in 2019. Vaccine 2021, 39, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Deng, G.; Cui, P.; Zeng, X.; Li, B.; Wang, D.; He, X.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Evolution of H7N9 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in the context of vaccination. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2343912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Zeng, X.; Cui, P.; Yan, C.; Chen, H. Alarming situation of emerging H5 and H7 avian influenza and effective control strategies. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2155072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Deng, G.; Ma, S.; Zeng, X.; Yin, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, B.; Cui, P.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; et al. Rapid evolution of H7N9 highly pathogenic viruses that emerged in China in 2017. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Deng, G.; Kong, H.; Gu, C.; Ma, S.; Yin, X.; Zeng, X.; Cui, P.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; et al. H7N9 virulent mutants detected in chickens in China pose an increased threat to humans. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 1409–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Zeng, X.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhao, C.; Qu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Gu, W.; et al. Genetic and biological characteristics of the globally circulating H5N8 avian influenza viruses and the protective efficacy offered by the poultry vaccine currently used in China. Sci. China Life Sci. 2022, 65, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Jiang, L.; Ye, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.; Wan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wen, X.; Liang, L.; Ma, S.; et al. TRIM35 mediates protection against influenza infection by activating TRAF3 and degrading viral PB2. Protein Cell 2020, 11, 894–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Chen, H.; Li, C. Advances in deciphering the interactions between viral proteins of influenza A virus and host cellular proteins. Cell Insight 2023, 2, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Liang, L.; Shao, X.; Luo, W.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, N.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Host Cellular Protein TRAPPC6ADelta Interacts with Influenza A Virus M2 Protein and Regulates Viral Propagation by Modulating M2 Trafficking. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Zhang, J.; Liang, L.; Wang, G.; Li, Q.; Zhu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, N.; et al. Phospholipid scramblase 1 interacts with influenza A virus NP, impairing its nuclear import and thereby suppressing virus replication. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Jiang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Kong, F.; Li, Q.; Yan, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, L.; et al. The G protein-coupled receptor FFAR2 promotes internalization during influenza A virus entry. J. Virol. 2020, 94, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; He, X.; Li, C.; Deng, G.; Shi, J.; Kong, H.; et al. Influenza virus uses mGluR2 as an endocytic receptor to enter cells. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1764–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Yin, X.; Shi, J.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, D.; et al. A genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 gene knockout screen identifies immunoglobulin superfamily DCC subclass member 4 as a key host factor that promotes influenza virus endocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, G.; Shi, W.; Hu, Y.; Wang, B.; Zeng, X.; Tian, G.; Deng, G.; Shi, J.; et al. Influenza A virus use of BinCARD1 to facilitate the binding of viral NP to importin α7 is counteracted by TBK1-p62 axis-mediated autophagy. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 1168–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Qiang, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, C.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; et al. Proteomic analysis of differentially expressed proteins in A549 cells infected with H9N2 avian influenza virus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yin, C.; Basit, Z.; Xia, B.; Liu, W. Dissection of influenza A virus M1 protein: pH-dependent oligomerization of N-terminal domain and dimerization of C-terminal domain. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Forouhar, F.; Qiu, S.; Sha, B.; Luo, M. The crystal structure of the influenza matrix protein M1 at neutral pH: M1-M1 protein interfaces can rotate in the oligomeric structures of M1. Virology 2001, 289, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, E.C.; Goddard, T.D.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Pearson, Z.J.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Liu, H.; Zhao, F.; Yuan, Q.; Ji, Y.; Cai, X.; He, X.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Wu, K.; et al. GPCR activation and GRK2 assembly by a biased intracellular agonist. Nature 2023, 620, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhri, A.; Xiao, Y.; Klee, A.N.; Wang, X.; Zhu, B.; Freeman, G.J. PD-L1 Binds to B7-1 Only In Cis on the Same Cell Surface. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, M.L.; Brookes, K.; Zha, L.; Manivannan, S.; Kim, J.; Kocbiyik, M.; Fletcher, A.; Gorvin, C.M.; Firth, G.; Fruhwirth, G.O.; et al. Combined Vorinostat and Chloroquine Inhibit Sodium–Iodide Symporter Endocytosis and Enhance Radionuclide Uptake In Vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 1352–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chassey, B.; Aublin-Gex, A.; Ruggieri, A.; Meyniel-Schicklin, L.; Pradezynski, F.; Davoust, N.; Chantier, T.; Tafforeau, L.; Mangeot, P.E.; Ciancia, C.; et al. The interactomes of influenza virus NS1 and NS2 proteins identify new host factors and provide insights for ADAR1 playing a supportive role in virus replication. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimova, G.; Pidoux, J.; Ullmann, A.; Ladant, D. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 5752–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, Y.J.; Suarez, C.D.; Hu, C.D. Visualization of AP-1 NF-kappaB ternary complexes in living cells by using a BiFC-based FRET. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.S.; Schwinn, M.K.; Hall, M.P.; Zimmerman, K.; Otto, P.; Lubben, T.H.; Butler, B.L.; Binkowski, B.F.; Machleidt, T.; Kirkland, T.A.; et al. NanoLuc Complementation Reporter Optimized for Accurate Measurement of Protein Interactions in Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Guo, J.; Gao, G.F.; Deng, T. Twenty natural amino acid substitution screening at the last residue 121 of influenza A virus NS2 protein reveals the critical role of NS2 in promoting virus genome replication by coordinating with viral polymerase. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0116623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Riching, K.; Lai, M.P.; Lu, D.; Cheng, R.; Qi, X.; Wang, J. Lysineless HiBiT and NanoLuc Tagging Systems as Alternative Tools for Monitoring Targeted Protein Degradation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shizukuishi, S.; Ogawa, M.; Kuroda, E.; Hamaguchi, S.; Sakuma, C.; Kakuta, S.; Tanida, I.; Uchiyama, Y.; Akeda, Y.; Ryo, A.; et al. Pneumococcal sialidase promotes bacterial survival by fine-tuning of pneumolysin-mediated membrane disruption. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh-hashi, K.; Hirata, Y. Elucidation of the Molecular Characteristics of Wild-Type and ALS-Linked Mutant SOD1 Using the NanoLuc Complementation Reporter System. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 190, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chheda, M.G.; Ashery, U.; Thakur, P.; Rettig, J.; Sheng, Z.H. Phosphorylation of Snapin by PKA modulates its interaction with the SNARE complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Q.; Lu, L.; Tian, J.H.; Zhu, Y.B.; Qiao, H.; Sheng, Z.H. Snapin-regulated late endosomal transport is critical for efficient autophagy-lysosomal function in neurons. Neuron 2010, 68, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Huang, Q.Q.; Birkett, R.; Doyle, R.; Dorfleutner, A.; Stehlik, C.; He, C.; Pope, R.M. SNAPIN is critical for lysosomal acidification and autophagosome maturation in macrophages. Autophagy 2017, 13, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, J.A.; Yoo, D.; Liu, H.C. Interaction of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus major envelope proteins GP5 and M with the cellular protein Snapin. Virus Res. 2018, 249, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ren, G.; Cui, X.; Lu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Qi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Ruan, Q. Host protein Snapin interacts with human cytomegalovirus pUL130 and affects viral DNA replication. J. Biosci. 2016, 41, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Qi, Y.; Ma, Y.; He, R.; Sun, Z.; Huang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Ruan, Q. Interaction between the human cytomegalovirus-encoded UL142 and cellular Snapin proteins. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 1069–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.; Lei, J.; Yang, E.; Pei, Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Gong, H.; Xiao, G.; Liu, F. Human cytomegalovirus primase UL70 specifically interacts with cellular factor Snapin. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 11732–11741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Shi, W.; Wen, F.; Qiang, H.; Liu, S.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. Targeted NanoBiT Screening Identifies a Novel Interaction Between SNAPIN and Influenza A Virus M1 Protein. Biology 2025, 14, 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121770

Zhang X, Wang H, Zhao C, Shi W, Wen F, Qiang H, Liu S, Li P, Chen X, Zhang C, et al. Targeted NanoBiT Screening Identifies a Novel Interaction Between SNAPIN and Influenza A Virus M1 Protein. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121770

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xiaoxuan, Huanhuan Wang, Conghui Zhao, Wenjun Shi, Faxin Wen, Haoxi Qiang, Sha Liu, Peilin Li, Xinhui Chen, Chunping Zhang, and et al. 2025. "Targeted NanoBiT Screening Identifies a Novel Interaction Between SNAPIN and Influenza A Virus M1 Protein" Biology 14, no. 12: 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121770

APA StyleZhang, X., Wang, H., Zhao, C., Shi, W., Wen, F., Qiang, H., Liu, S., Li, P., Chen, X., Zhang, C., Huang, J., Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., & Ma, S. (2025). Targeted NanoBiT Screening Identifies a Novel Interaction Between SNAPIN and Influenza A Virus M1 Protein. Biology, 14(12), 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121770