Contrasting La Crosse Virus Lineage III Vector Competency in Two Geographical Populations of Aedes triseriatus and Aedes albopictus Mosquitoes

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

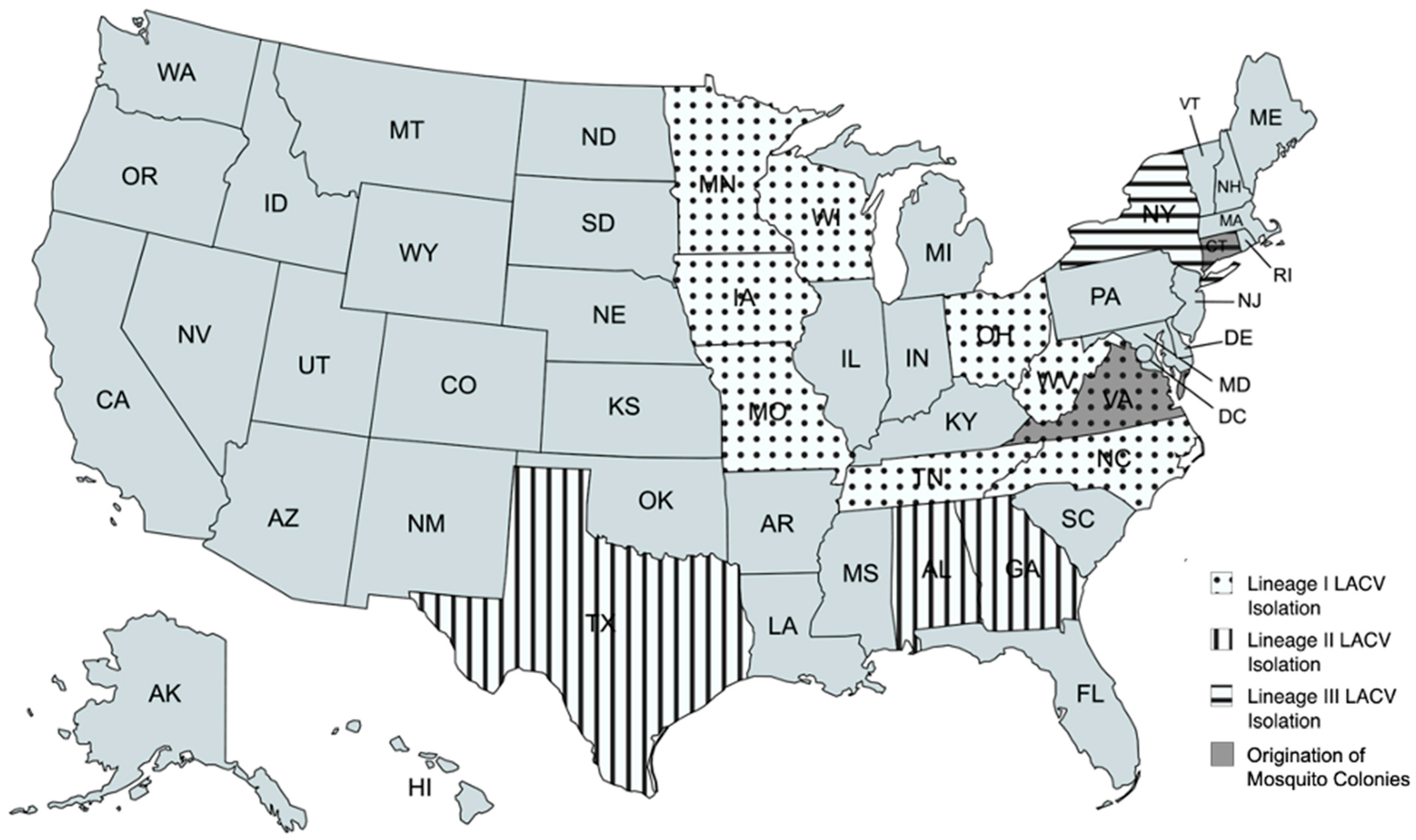

2.1. Mosquito Populations

2.2. Viral Transmission Assays

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

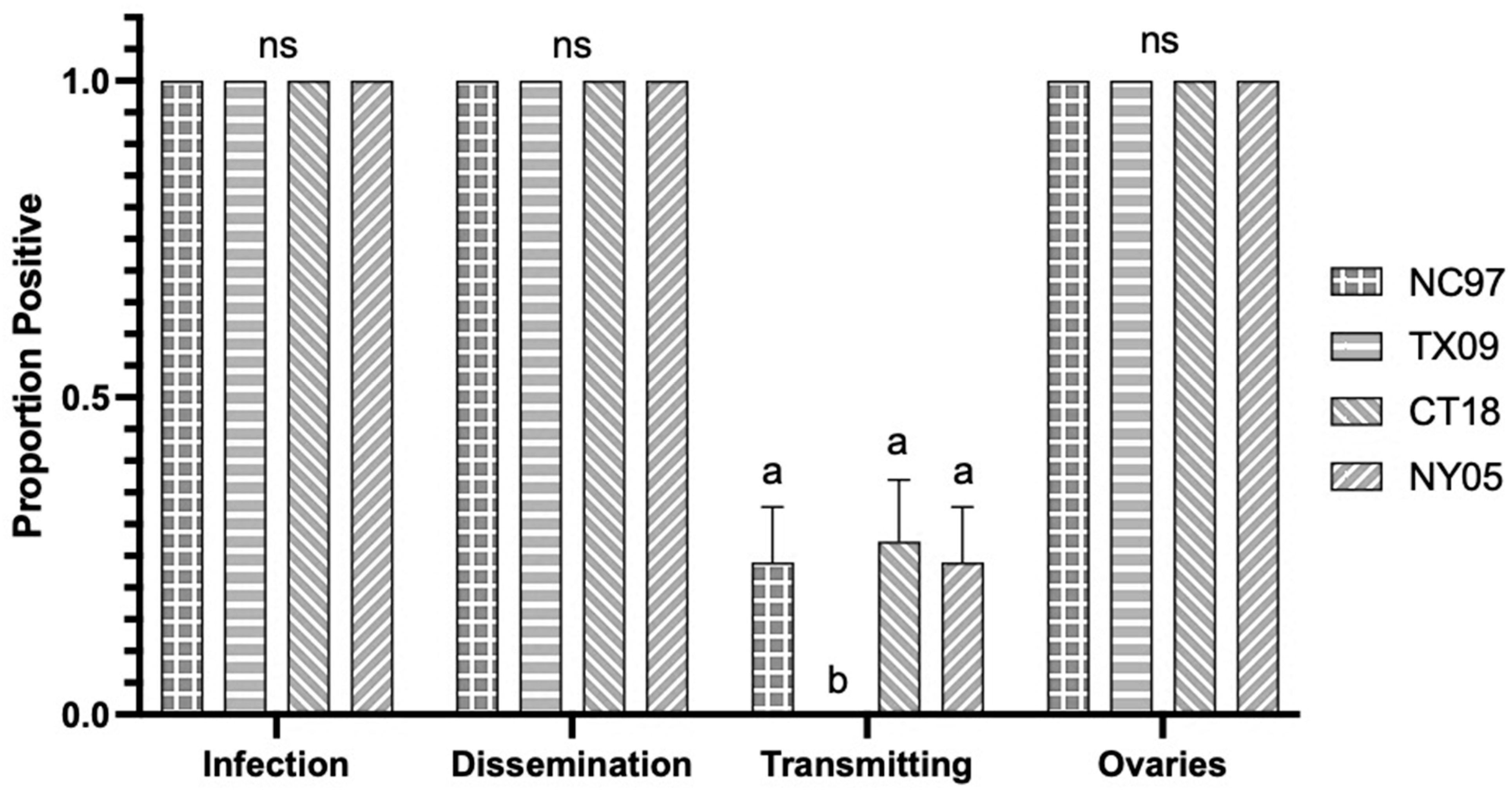

3.1. LACV Competency in Connecticut Aedes triseriatus

3.1.1. Oral Infection

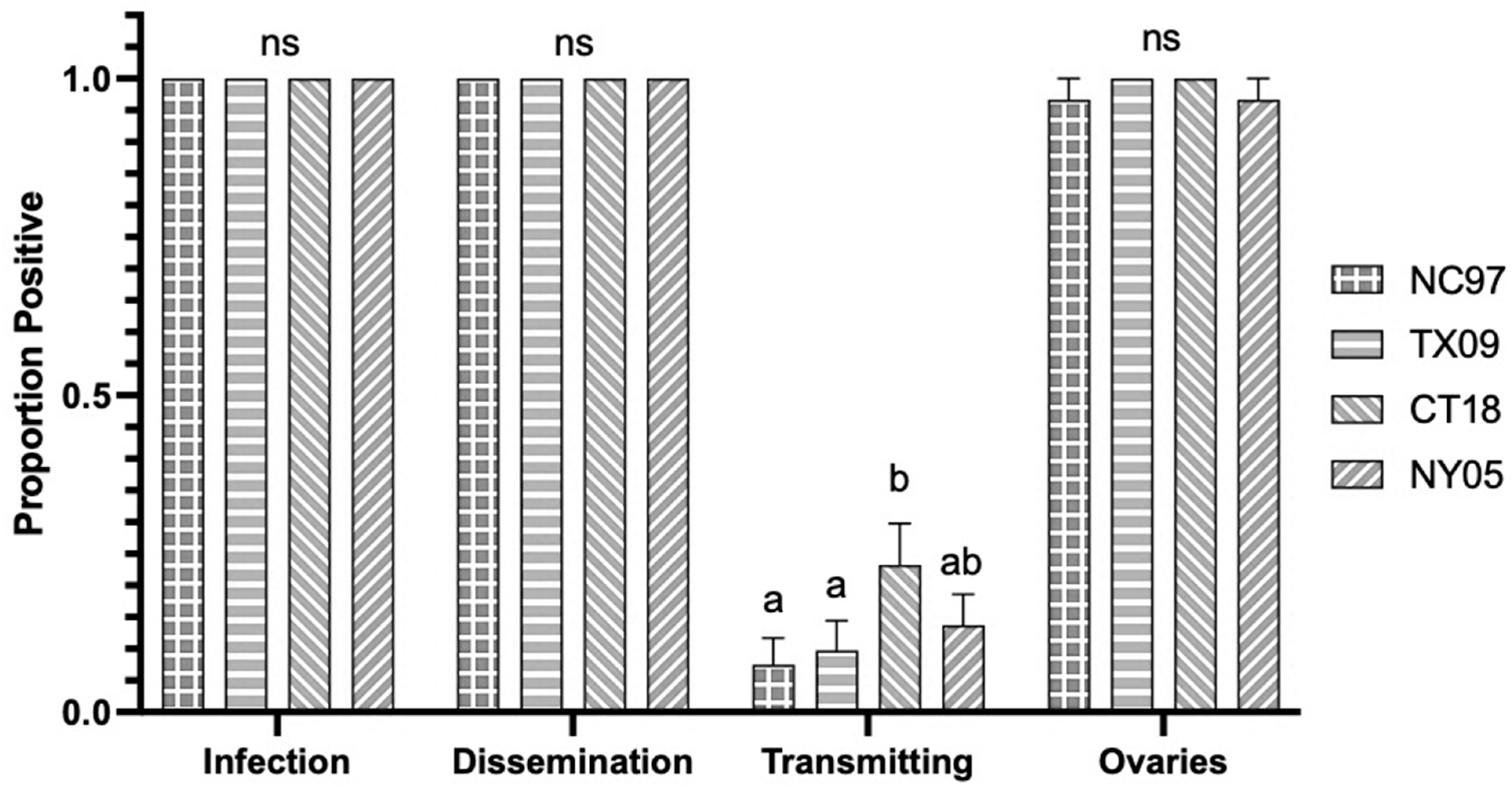

3.1.2. Intrathoracic Inoculation

3.2. LACV Competency in Connecticut Aedes albopictus

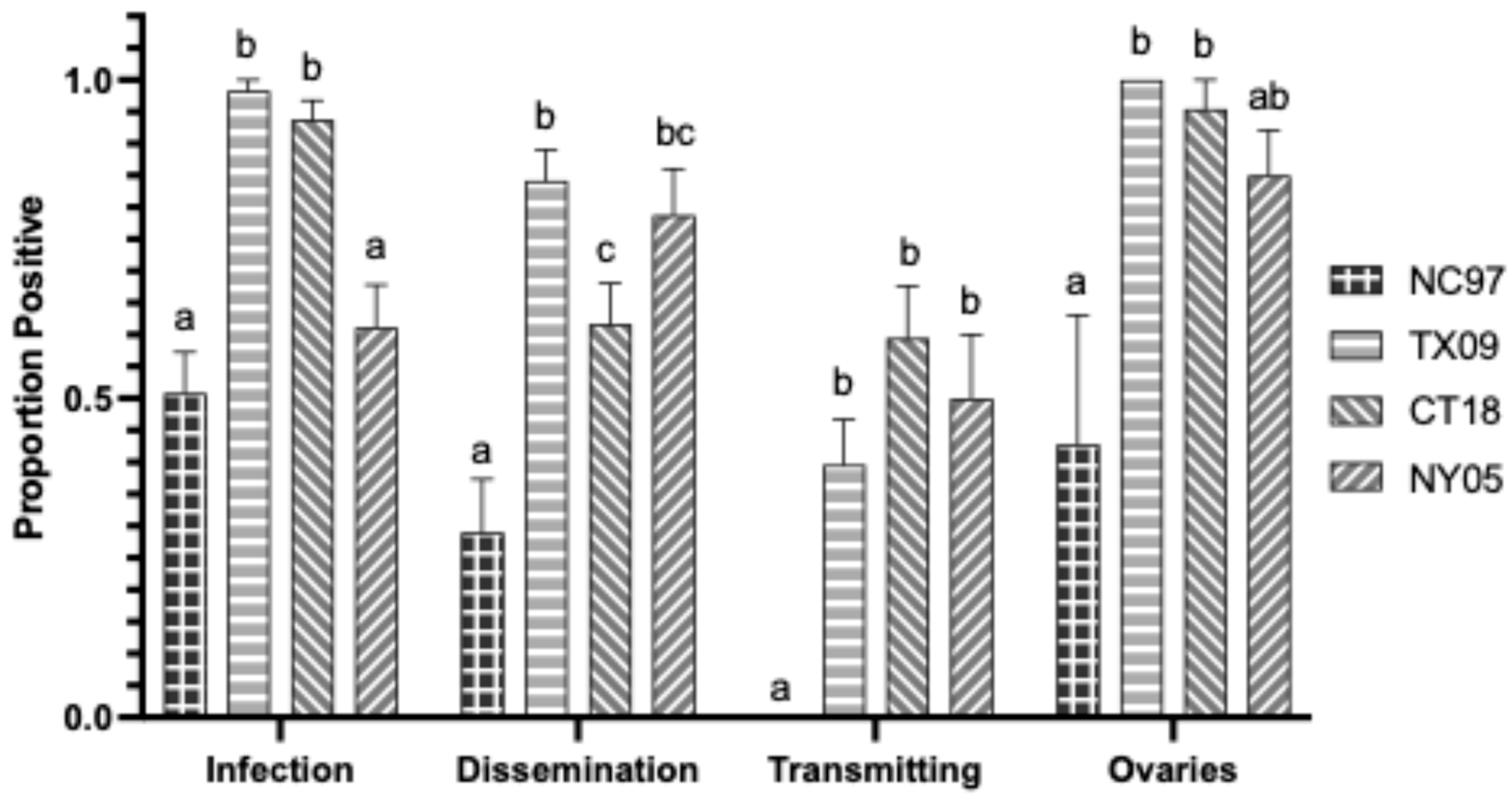

3.2.1. Oral Infection

3.2.2. Intrathoracic Inoculation

3.3. Variation Between Mosquito Species from Connecticut

3.4. LACV Competency in Virginia Aedes triseriatus

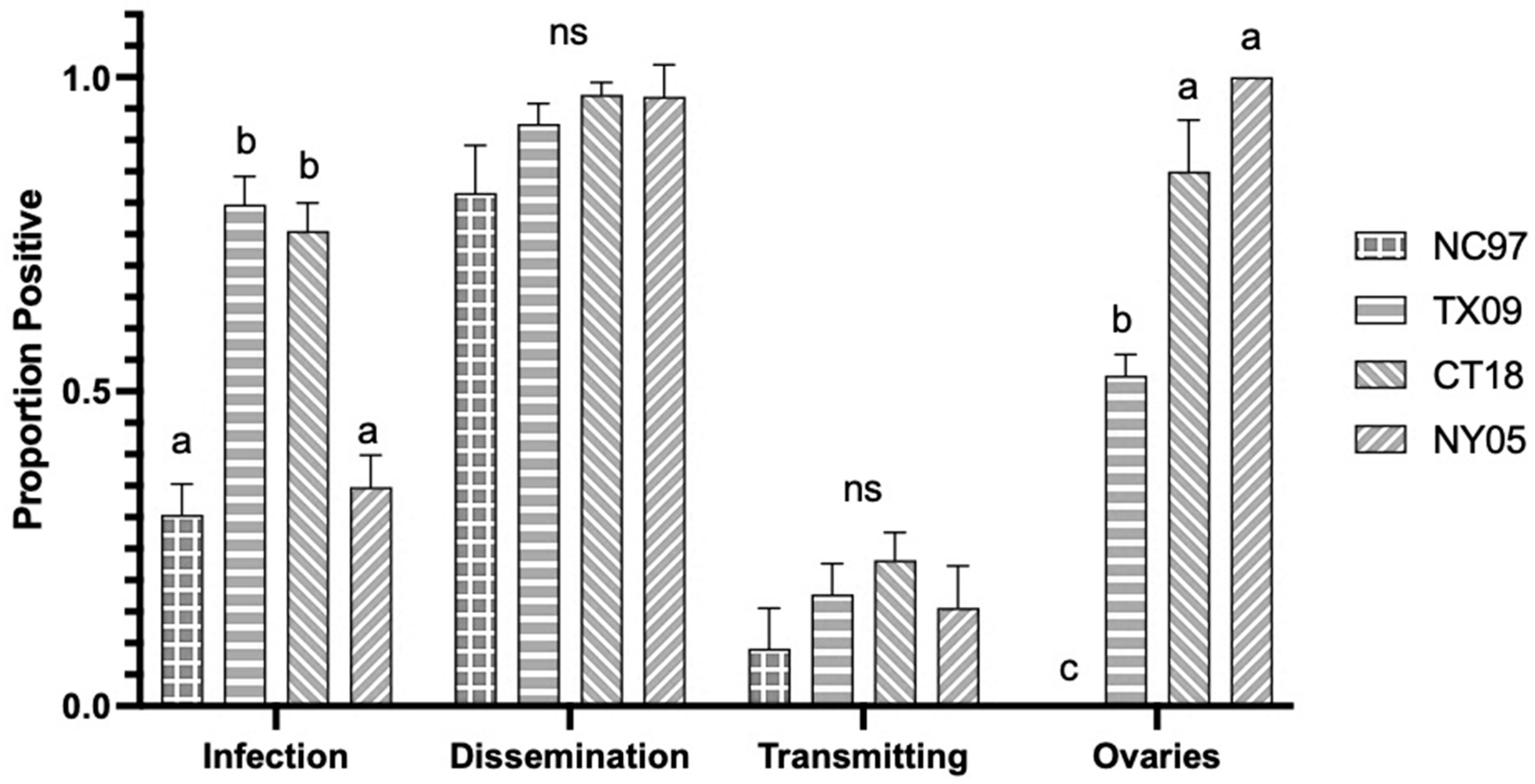

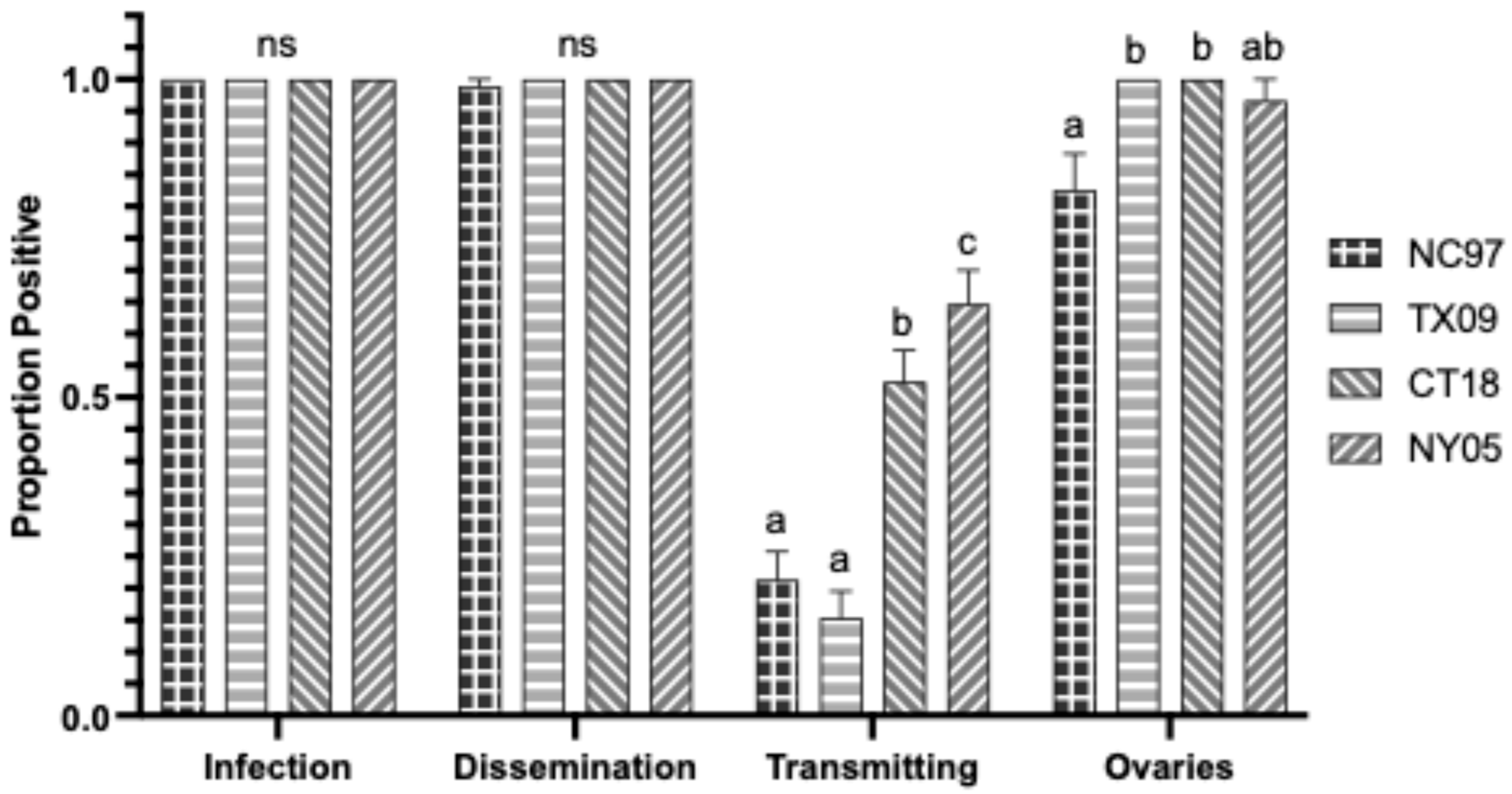

3.4.1. Oral Infection

3.4.2. Intrathoracic Inoculation

3.5. LACV Competency in Virginia Aedes albopictus

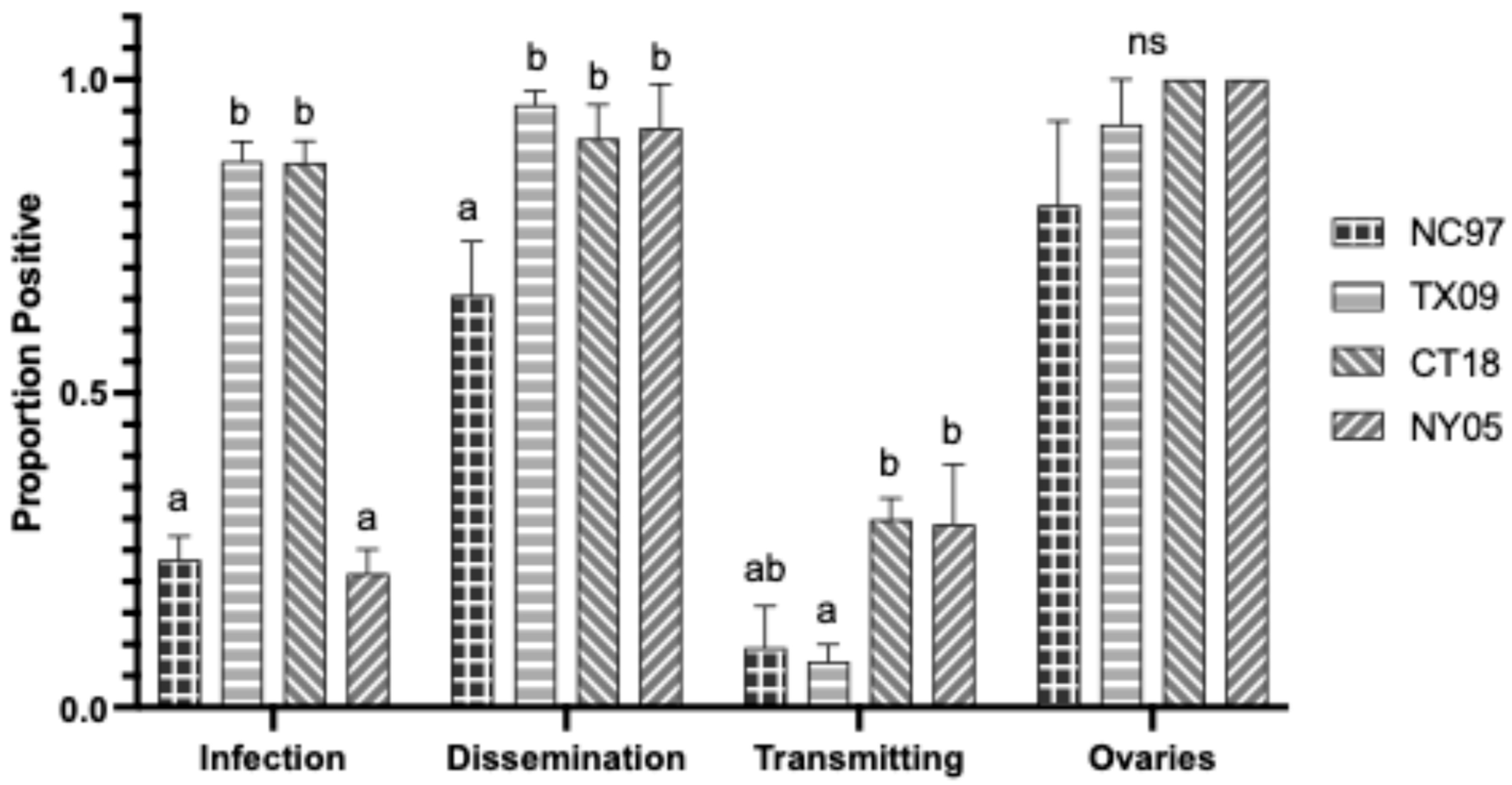

3.5.1. Oral Infection

3.5.2. Intrathoracic Inoculation

3.6. Variation Between Mosquito Species from Virginia

3.6.1. Oral Infection

3.6.2. Intrathoracic Inoculation Variation

3.7. Overall Geographic Variation in LACV Vector Competency

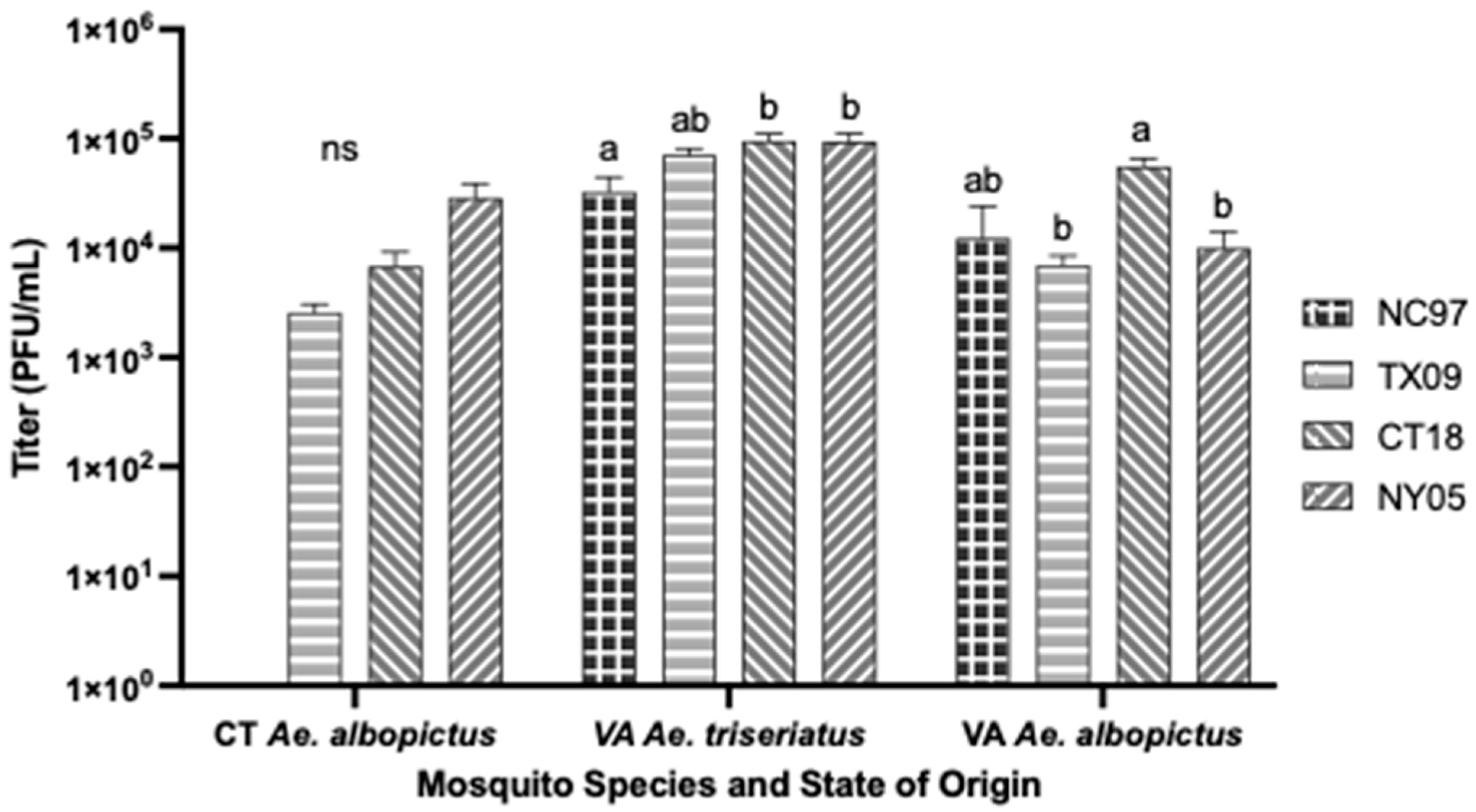

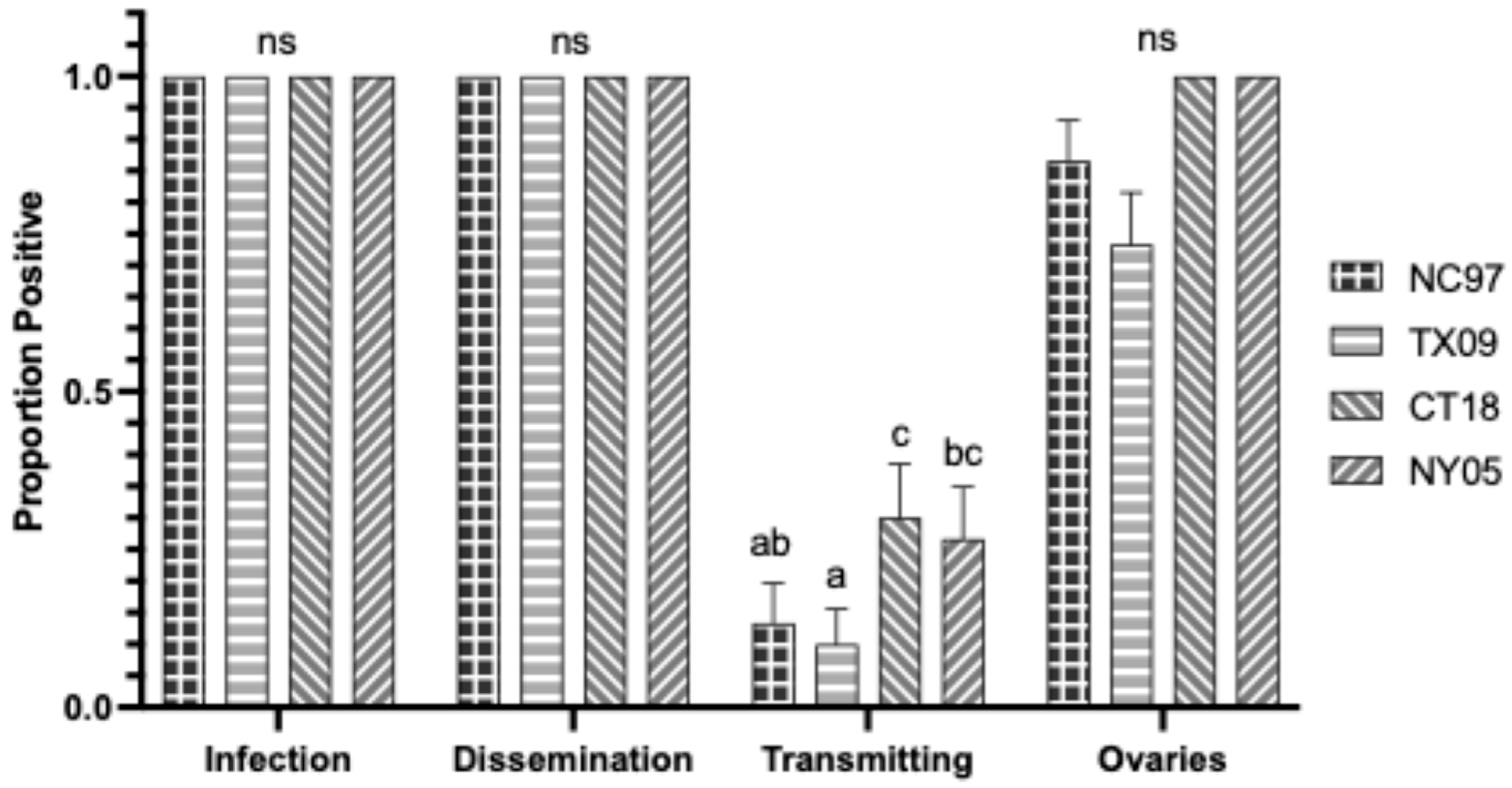

3.7.1. Aedes triseriatus Intrathoracic Inoculation

3.7.2. Aedes albopictus Intrathoracic Inoculation

3.7.3. Aedes albopictus Oral Infection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| CT Aedes triseriatus LACV Exposure by Intrathoracic Inoculation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus Strain (Lineage) | |||||

| Trial | Transmission Parameter | NC97 (I) | TX09 (II) | CT18 (III) | NY05 (III) |

| 1 | Infection (bodies) | 1.00 (25/25) a | 1.00 (23/23) a | 1.00 (12/12) a | 1.00 (25/25) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 1.00 (25/25) a | 1.00 (23/23) a | 1.00 (12/12) a | 1.00 (25/25) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.24 (6/25) a | 0.00 (0/23) b | 0.33 (4/12) a | 0.24 (6/25) a | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 1.00 (25/25) a | 1.00 (23/23) a | 1.00 (12/12) a | 1.00 (25/25) a | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 1.5 × 103 pfu/mL a (±2.8 × 102 pfu/mL) | 2.2 × 103 pfu/mL a (±5.2 × 102 pfu/mL) | 3.6 × 103 pfu/mL a (±8.1 × 102 pfu/mL) | 3.2 × 103 pfu/mL a (±1.4 × 103 pfu/mL) | |

| 2 | Infection (bodies) | NA | 1.00 (13/13) a | 1.00 (10/10) a | NA |

| Dissemination (legs) | NA | 1.00 (13/13) a | 1.00 (10/10) a | NA | |

| Transmission (saliva) | NA | 0.00 (0/13) a | 0.20 (2/10) b | NA | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | NA | 1.00 (13/13) a | 1.00 (10/10) a | NA | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | NA | 8.3 × 102 pfu/mL a (±3.2 × 102 pfu/mL) | 4.3 × 103 pfu/mL a (±1.0 × 103 pfu/mL) | NA | |

| TOTALS: | Infection (bodies) | 1.00 (25/25) a | 1.00 (36/36) a | 1.00 (22/22) a | 1.00 (25/25) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 1.00 (25/25) a | 1.00 (36/36) a | 1.00 (22/22) a | 1.00 (25/25) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.24 (6/25) a | 0.00 (0/36) b | 0.27 (6/22) a | 0.24 (6/25) a | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 1.00 (25/25) a | 1.00 (36/36) a | 1.00 (22/22) a | 1.00 (25/25) a | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 1.5 × 103 pfu/mL a (±2.8 × 102 pfu/mL) | 1.7 × 103 pfu/mL a (±3.6 × 102 pfu/mL) | 3.9 × 103 pfu/mL a (±6.3 × 102 pfu/mL) | 3.2 × 103 pfu/mL a (±1.4 × 103 pfu/mL) | |

| CT Aedes albopictus LACV Exposure by Oral Feeding | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LACV Strain (Lineage) | |||||

| Trial | Transmission Parameter | NC97 (I) | TX09 (II) | CT18 (III) | NY05 (III) |

| 1 | Infection (bodies) | 0.33 (4/12) a | 0.83 (5/6) b | 1 (14/14) b | 0.63 (5/8) ab |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.08 (1/12) a | 0.83 (5/6) bc | 1 (14/14) c | 0.50 (4/8) ab | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.00 (0/12) a | 0.50 (3/6) bc | 0.64 (9/14) c | 0.13 (1/8) ab | |

| 2 | Infection (bodies) | 0.73 (22/30) bc | 0.97 (37/38) a | 0.88 (35/40) ab | 0.59 (24/41) c |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.70 (21/30) bc | 0.92 (35/38) a | 0.88 (35/40) ab | 0.54 (22/41) c | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.07 (2/30) a | 0.03 (1/38) a | 0.05 (2/40) a | 0.07 (3/41) a | |

| 3 | Infection (bodies) | 0.00 (0/17) a | 0.30 (3/10) ab | 0.40 (4/10) b | 0.15 (2/13) ab |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.00 (0/17) a | 0.30 (3/10) a | 0.30 (3/10) a | 0.15 (2/13) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.00 (0/17) a | 0.20 (2/10) a | 0.20 (2/10) a | 0.08 (1/13) a | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.00 (0/17) a | 0.30 (3/10) a | 0.30 (3/10) a | 0.15 (2/13) a | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 0 pfu/mL a (±0 pfu/mL) | 7.5 × 103 pfu/mL a (±3.4 × 103 pfu/mL) | 7.7 × 102 pfu/mL a (±5.0 × 102 pfu/mL) | 3.5 × 104 pfu/m b (±2.3 × 104 pfu/mL) | |

| 4 | Infection (bodies) | 0.00 (0/30) a | 0.73 (22/30) b | 0.60 (18/30) b | 0.1 (3/30) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.00 (0/30) a | 0.63 (19/30) b | 0.57 (17/30) b | 0.10 (3/30) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.00 (0/30) a | 0.17 (5/30) a | 0.10 (3/30) a | 0.00 (0/30) a | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.00 (0/30) a | 0.60 (18/30) b | 0.50 (15/30) b | 0.10 (3/30) a | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 0 pfu/mL a (±0 pfu/mL) | 1.7 × 103 pfu/mL a (±4.0 × 102 pfu/mL) | 8.9 × 103 pfu/mL b (±3.0 × 103 pfu/mL) | 2.5 × 104 pfu/mL c (±1.2 × 104 pfu/mL) | |

| TOTALS: | Infection (bodies) | 0.30 (27/89) a | 0.80 (67/84) b | 0.76 (71/94) b | 0.35 (32/92) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.25 (22/89) a | 0.75 (62/84) b | 0.73 (69/94) b | 0.34 (31/92) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.02 (2/89) a | 0.13 (11/84) a | 0.17 (16/94) a | 0.05 (5/92) a | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.00 (0/30) a | 0.53 (21/40) b | 0.43 (17/40) b | 0.16 (5/32) a | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 0 pfu/mL a (±0 pfu/mL) | 2.6 × 103 pfu/mL a (±5.1 × 102 pfu/mL) | 6.8 × 103 pfu/mL a (±7.1 × 102 pfu/mL) | 2.9 × 104 pfu/mL a (±2.2 × 103 pfu/mL) | |

| CT Aedes albopictus LACV Exposure by Intrathoracic Inoculation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LACV Strain (Lineage) | |||||

| Trial | Transmission Parameter | NC97 (I) | TX09 (II) | CT18 (III) | NY05 (III) |

| 1 | Infection (bodies) | 1.00 (30.30) a | 1.00 (30.30) a | 1.00 (24/24) a | 1.00 (30.30) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (24/24) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.03 (1/30) a | 0.10 (3/30) a | 0.42 (10/24) b | 0.13 (4/30) ab | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.97 (29/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (24/24) a | 0.97 (29/30) a | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 1.1 × 103 pfu/mL a (±3.2 × 102 pfu/mL) | 2.6 × 103 pfu/mL a (±5.0 × 102 pfu/mL) | 3.4 × 103 pfu/mL a (±7.1 × 102 pfu/mL) | 9.0 × 103 pfu/mL b (±2.3 × 103 pfu/mL) | |

| VA Aedes triseriatus LACV Exposure by Oral Feeding | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Transmission Parameter | NC97 | TX09 | CT18 | NY05 |

| 1 | Infection (bodies) | 0.38 (6/16) a | 0.94 (17/18) b | 0.95 (21/22) b | 0.31 (5/16) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.13 (2/16) a | 0.72 (13/18) b | 0.32 (7/22) a | 0.19 (3/16) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.00 (0/16) a | 0.28 (5/18) a | 0.23 (5/22) a | 0.06 (1/16) a | |

| 2 | Infection (bodies) | 0.53 (8/15) a | 1 (10/10) b | 0.75 (9/12) ab | 0.75 (6/8) ab |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.00 (0/15) a | 0.80 (8/10) b | 0.67 (8/12) b | 0.38 (3/8) ab | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.00 (0/15) a | 0.40 (4/10) ab | 0.67 (8/12) b | 0.13 (1/8) a | |

| 3 | Infection (bodies) | 0.57 (17/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) b | 1.00 (30/30) b | 0.73 (22/30) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.23 (7/30) a | 0.90 (27/30) b | 0.73 (22/30) b | 0.67 (20/30) b | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.00 (0/30) a | 0.37 (10/27) b | 0.30 (9/30) b | 0.37 (11/30) b | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.43 (3/30) a | 0.93 (27/30) b | 0.70 (21/30) bc | 0.85 (17/30) c | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 3.3 × 104 pfu/mL a (±1.8 × 104 pfu/mL) | 7.0 × 104 pfu/mL ab (±1.1 × 104 pfu/mL) | 9.6 × 104 pfu/mL b (±1.6 × 104 pfu/mL) | 9.5 × 104 pfu/mL b (±1.9 × 104 pfu/mL) | |

| TOTALS: | Infection (bodies) | 0.51 (31/61) a | 0.98 (57/58) b | 0.94 (60/64) b | 0.61 (33/54) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.15 (9/61) a | 0.83 (48/58) b | 0.58 (37/64) c | 0.48 (26/54) c | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.00 (0/61) a | 0.33 (19/58) b | 0.34 (22/64) b | 0.24 (13/54) b | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.1 (3/30) a | 0.93 (27/30) b | 0.70 (21/30) bc | 0.56 (17/30) c | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 3.3 × 104 pfu/mL a (±1.8 × 104 pfu/mL) | 7.0 × 104 pfu/mL ab (±1.1 × 104 pfu/mL) | 9.6 × 104 pfu/mL b (±1.6 × 104 pfu/mL) | 9.5 × 104 pfu/mL b (±1.9 × 104 pfu/mL) | |

| VA Aedes triseriatus LACV Exposure by Intrathoracic Inoculation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LACV Strain (Lineage) | |||||

| Trial | Transmission Parameter | NC97 (I) | TX09 (II) | CT18 (III) | NY05 (III) |

| 1 | Infection (bodies) | 1.00 (44/44) a | 1.00 (48/48) a | 1.00 (43/43) a | 1.00 (52/52) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.98 (43/44) a | 1.00 (48/48) a | 1.00 (43/43) a | 1.00 (52/52) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.18 (8/44) a | 0.17 (8/48) a | 0.74 (32/43) b | 0.67 (35/52) b | |

| 2 | Infection (bodies) | 1.00 (16/16) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 1.00 (16/16) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.25 (4/16) bc | 0.13 (4/30) c | 0.33 (10/30) b | 0.60 (18/30) a | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.50 (8/16) b | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 0.97 (29/30) a | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 4.9 × 102 pfu/mL a (±8.3 × 101 pfu/mL) | 7.9 × 102 pfu/mL a (±1.3 × 102 pfu/mL) | 2.1 × 103 pfu/mL a (±3.1 × 102 pfu/mL) | 1.2 × 103 pfu/mL a (±3.0 × 102 pfu/mL) | |

| 3 | Infection (bodies) | 1.00 (30/30) a | NA | 1.00 (30/30) a | NA |

| Dissemination (legs) | 1.00 (30/30) a | NA | 1.00 (30/30) a | NA | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.23 (7/30) a | NA | 0.40 (12/30) b | NA | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 1.00 (30/30) a | NA | 1.00 (30/30) a | NA | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 3.5 × 103 pfu/mL a (±1.8 × 103 pfu/mL) | NA | 1.0 × 104 pfu/mL a (±3.4 × 103 pfu/mL) | NA | |

| TOTALS: | Infection (bodies) | 1.00 (90/90) a | 1.00 (78/78) a | 1.00 (103/103) a | 1.00 (82/82) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.99 (89/90) a | 1.00 (78/78) a | 1.00 (103/103) a | 1.00 (82/82) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.21 (19/90) a | 0.15 (12/78) a | 0.52 (54/103) b | 0.65 (53/82) c | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.83 (38/46) a | 1.00 (30/30) b | 1.00 (60/60) b | 0.97 (29/30) ab | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 2.9 × 103 pfu/mL ab (±1.3 × 103 pfu/mL) | 7.9 × 102 pfu/mL b (±1.3 × 102 pfu/mL) | 6.2 × 103 pfu/mL a (±1.8 × 103 pfu/mL) | 1.2 × 103 pfu/mL b (±3.0 × 102 pfu/mL) | |

| VA Aedes albopictus LACV Exposure by Oral Feeding | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LACV Strain (Lineage) | |||||

| Trial | Transmission Parameter | NC97 (I) | TX09 (II) | CT18 (III) | NY05 (III) |

| 1 | Infection (bodies) | 0.32 (12/37) a | 1 (31/31) b | 1 (31/31) b | 0.79 (11/14) b |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.24 (9/37) a | 1 (31/31) b | 1 (31/31) b | 0.64 (9/14) c | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.03 (1/37) a | 0.06 (2/31) a | 0.39 (12/31) b | 0.36 (5/14) b | |

| 2 | Infection (bodies) | 0.12 (8/69) a | 0.98 (53/54) b | 0.92 (34/37) b | 0.13 (6/48) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.03 (2/69) a | 0.94 (51/54) b | 0.76 (28/37) c | 0.08 (4/48) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.01 (1/69) a | 0.06 (3/54) ab | 0.16 (6/37) b | 0 (0/48) a | |

| 3 | Infection (bodies) | 0.40 (12/30) b | NA | 0.67 (20/30) a | 0.30 (9/30) b |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.33 (10/30) b | NA | 0.60 (18/30) a | 0.30 (9/30) b | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.00 (0/30) a | NA | 0.17 (5/30) a | 0.07 (2/30) a | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.27 (8/30) b | NA | 0.60 (18/30) a | 0.30 (9/30) b | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 1.2 × 104 pfu/mL ab (±1.2 × 104 pfu/mL) | NA | 5.5 × 104 pfu/mL a (±1.1 × 104 pfu/mL) | 7.3 × 103 pfu/mL b (±4.3 × 103 pfu/mL) | |

| 4 | Infection (bodies) | NA | 0.53 (16/30) a | NA | 0.07 (2/30) b |

| Dissemination (legs) | NA | 0.47 (14/30) a | NA | 0.07 (2/30) b | |

| Transmission (saliva) | NA | 0.07 (2/30) a | NA | 0.00 (0/30) a | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | NA | 0.43 (13/30) a | NA | 0.07 (2/30) b | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | NA | 7.0 × 103 pfu/mL a (±1.5 × 103 pfu/mL) | NA | 2.2 × 104 pfu/mL a (±1.2 × 104 pfu/mL) | |

| TOTAL: | Infection (bodies) | 0.24 (32/136) a | 0.87 (100/115) b | 0.87 (85/98) b | 0.21 (26/122) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 0.15 (21/136) a | 0.83 (96/115) b | 0.79 (77/98) b | 0.20 (24/122) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.01 (2/136) a | 0.06 (7/115) a | 0.23 (23/98) b | 0.06 (7/122) a | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.27 (8/30) bc | 0.43 (13/30) ab | 0.60 (18/30) a | 0.18 (11/60) c | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 1.2 × 104 pfu/mL ab (±1.2 × 104 pfu/mL) | 7.0 × 103 pfu/mL a (±1.5 × 103 pfu/mL) | 5.5 × 104 pfu/mL b (±1.1 × 104 pfu/mL) | 1.0 × 104 pfu/mL a (±4.3 × 103 pfu/mL) | |

| VA Aedes albopictus LACV Exposure by Intrathoracic Inoculation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LACV Strain (lineage) | |||||

| Trial | Transmission Parameter | NC97 (I) | TX09 (II) | CT18 (III) | NY05 (III) |

| 1 | Infection (bodies) | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a |

| Dissemination (legs) | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | |

| Transmission (saliva) | 0.13 (4/30) ab | 0.10 (3/30) a | 0.30 (9/30) c | 0.27 (8/30) bc | |

| Vertical (positive ovaries) | 0.87 (26/30) a | 0.73 (22/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | 1.00 (30/30) a | |

| Mean (SE) Positive Ovaries | 1.2 × 103 pfu/mL a (±3.1 × 102 pfu/mL) | 7.6 × 102 pfu/mL a (±2.5 × 102 pfu/mL) | 2.9 × 103 pfu/mL a (±1.5 × 103 pfu/mL) | 1.2 × 103 pfu/mL a (±5.9 × 102 pfu/mL) | |

References

- Thompson, W.H.; Kalfayan, B.; Anslow, R.O. Isolation of California Encephalitis Group Virus from a Fatal Human Illness. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1965, 81, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.C.; Reisen, W.K. Present and Future Arboviral Threats. Antivir. Res. 2010, 85, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.F.; Craig, A.S.; Nasci, R.S.; Patterson, L.E.R.; Erwin, P.C.; Gerhardt, R.R.; Ussery, X.T.; Schaffner, W. Newly Recognized Focus of La Crosse Encephalitis in Tennessee. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999, 28, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewick, S.; Agusto, F.; Calabrese, J.M.; Muturi, E.J.; Fagan, W.F. Epidemiology of La Crosse Virus Emergence, Appalachia Region, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 1921–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McJunkin, J.E.; de los Reyes, E.C.; Irazuzta, J.E.; Caceres, M.J.; Khan, R.R.; Minnich, L.L.; Fu, K.D.; Lovett, G.D.; Tsai, T.; Thompson, A. La Crosse Encephalitis in Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaensbauer, J.T.; Lindsey, N.P.; Messacar, K.; Staples, J.E.; Fischer, M. Neuroinvasive Arboviral Disease in the United States: 2003 to 2012. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e642–e650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Data and Maps for La Crosse. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/la-crosse-encephalitis/data-maps/index.html (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Balfour, H.H., Jr.; Siem, R.A.; Bauer, H.; Quie, P.G. California Arbrovirus (La Crosse) Infections. I. Clinical and Laboratory Findings in 66 Children with Meningoencephalitis. Pediatrics 1973, 52, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, S.; Greig, J.; Mascarenhas, M.; Young, I.; Waddell, L.A. La Crosse Virus: A Scoping Review of the Global Evidence. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 147, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rust, R.S.; Thompson, W.H.; Matthews, C.G.; Beaty, B.J.; Chun, R.W.M. Topical Review: La Crosse and Other Forms of California Encephalitis. J. Child. Neurol. 2016, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virus Taxonomy: The Database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Available online: https://ictv.global/taxonomy/ (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—About La Crosse Virus. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/la-crosse-encephalitis/about/index.html (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Byrd, B.D. La Crosse Encephalitis: A Persistent Arboviral Threat in North Carolina. North Carol. Med. J. 2016, 77, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, P.C.; Jones, T.F.; Gerhardt, R.R.; Halford, S.K.; Smith, A.B.; Patterson, L.E.R.; Gottfried, K.L.; Burkhalter, K.L.; Nasci, R.S.; Schaffner, W. La Crosse Encephalitis in Eastern Tennessee: Clinical, Environmental, and Entomological Characteristics from a Blinded Cohort Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 155, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borucki, M.K.; Kempf, B.J.; Blitvich, B.J.; Blair, C.D.; Beaty, B.J. La Crosse Virus: Replication in Vertebrate and Invertebrate Hosts. Microbes Infect. 2002, 4, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, K.S.; Muturi, E.J.; Montgomery, A.V.; Alto, B.W. Effect of Oral Infection of La Crosse Virus on Survival and Fecundity of Native Ochlerotatus triseriatus and Invasive Stegomyia albopicta. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2014, 28, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calisher, C.H. Medically Important Arboviruses of the United States and Canada. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 7, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leisnham, P.; Juliano, S.A. Impacts of Cimate, Land Use, and Biological Invasion on the Ecology of Immature Aedes mosquitoes: Implications for La Crosse Emergence. Ecohealth 2012, 9, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, D.M.; Pantuwantana, S.; DeFoliart, G.R.; Yuill, T.M.; Thompson, W.H. Transovarial Transmission of La Crosse Virus (California Encephalitis Group) in the Mosquito, Aedes triseriatus. Science 1973, 182, 1140–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westby, K.M.; Juliano, S.A. Simulated Seasonal Photoperiods and Fluctuating Temperatures Have Limited Effects on Blood Feeding and Life History in Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2015, 52, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantuwatana, S.; Thompson, W.H.; Watts, D.M.; Yuill, T.M.; Hanson, R.P. Isolation of La Crosse Virus from Field Collected Aedes triseriatus Larvae. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1974, 23, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, B.J.; Blair, C.D.; Beaty, B.J. Quantitative Analysis of La Crosse Virus Transcription and Replication in Cell Cultures and Mosquitoes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006, 74, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.R.; DeFoliart, G.R.; Yuill, T.M. Vertical Transmission of La Crosse Virus (California Encephalitis Group): Transovarial and Filial Infection Rates in Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1977, 14, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, S.M.; Beaty, M.K.; Gabitzsch, E.S.; Blair, C.D.; Beaty, B.J. Aedes triseriatus Females Transovarially-Infected with La Crosse Virus Mate More Efficiently Than Uninfected Mosquitoes. J. Med. Entomol. 2009, 46, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, G.; Shepard, J.J.; Misencik, M.J.; Andreadis, T.G.; Armstrong, P.M. Local Persistence of Novel Regional Variants of La Crosse Virus in the Northeast USA. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, R.M. Bunyaviruses and Climate Change. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009, 15, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergren, N.A.; Kading, R.C. The Ecological Significance and Implications of Transovarial Transmission Among the Vector-Borne Bunyaviruses: A Review. Insects 2018, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaty, B.J.; Thompson, W.H. Delination of La Crosse Virus in Developmental Stages of Transovarially Infected Aedes triseriatus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1976, 25, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, W.H. Higher Venereal Infection and Transmission Rates with La Crosse Virus in Aedes triseriatus Engorged Before Mating. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1979, 28, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, P.M.; Andreadis, T.G. A New Genetic Variant of La Crosse Virus (Bunyaviridae) Isolated from New England. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006, 75, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimstad, P.R.; Kobayashi, J.F.; Zhang, M.B.; Craig, G.B. Recently Introduced Aedes Albopictus in the United States: Potential Vector of La Crosse Virus (Bunyaviridae: California Serogroup). J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1989, 5, 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.C.; Dotseth, E.J.; Jackson, B.T.; Zink, S.D.; Marek, P.E.; Kramer, L.D.; Paulson, S.L.; Hawley, D.M. La Crosse Virus in Aedes Japonicus Japonicus Mosquitoes in the Appalachian Region, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, R.R.; Gottfried, K.L.; Apperson, C.S.; Davis, B.S.; Erwin, P.C.; Smith, A.B.; Panella, N.A.; Powell, E.E.; Nasci, R.S. First Isolation of La Crosse Virus from Naturally Infected Aedes albopictus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001, 7, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westby, K.M.; Fritzen, C.; Paulsen, D.; Poindexter, S.; Moncayo, A.C. La Crosse Encephalitis Virus Infection in Field-Collected Aedes albopictus, Aedes japonicus, and Aedes triseriatus in Tennessee. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2015, 31, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimstad, P.R.; Craig, G.B., Jr. Aedes triseriatus and La Crosse Virus: Geographic Variation in Vector Susceptibility and Ability to Transmit. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1977, 26, 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.R.; Beaty, B.J.; Lorenz, L.H. Variation of La Crosse Virus Filial Infection Rates in Geographic Strains of Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1982, 19, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodring, J.; Chandler, L.J.; Oray, C.T.; McGaw, M.M.; Blair, C.D.; Beaty, B.J. Short Report: Diapause, Transovarial Transmission, and Filial Infection Rates in Geographic Strains of La Crosse Virus-Infected Aedes triseriatus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1998, 58, 587–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, Y.-H.; Song, Z.; Hu, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhong, D.; Zheng, X. Vector Competence for DENV-2 Among Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) Populations in China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 649975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.F.; Binduga-Gajewska, I.; Kauffman, E.B.; Kramer, L.D. Quantitation of Flaviviruses by Fluorescent Focus Assay. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 134, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, A.W.E.; Kantor, A.M.; Passarelli, A.L.; Clem, R.J. Tissue Barriers to Arbovirus Infection in Mosquitoes. Viruses 2015, 7, 3741–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, J.L.; Houk, E.J.; Kramer, L.D.; Reeves, W.C. Intrinsic Factors Affecting Vector Competence of Mosquitoes for Arboviruses. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1983, 28, 229–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimstad, P.R.; Walker, E.D. Aedes triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) and La Crosse Virus. IV. Nutritional Deprivation of Larvae Affects the Adult Barriers to Infection and Transmission. J. Med. Entomol. 1991, 28, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, S.L.; Grimstad, P.R.; Craig, G.B. Midgut and Salivary Gland Barriers to La Crosse Virus Dissemination in Mosquitoes of the Aedes triseriatus Group. Med. Vet. Entomol. 1989, 3, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.E.; Wu, W.-K.; Verleye, D.; Rai, K.S. Midgut Basal Lamina Thickness and Dengue-1 Virus Dissemination Rates in Laboratory Strains of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1993, 30, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.T.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Reagan, K.L.; Blair, C.D.; Beaty, B.J. Comparative Potential of Aedes triseriatus, Aedes albopictus, and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) to Transovarially Transmit La Crosse Virus. J. Med. Entomol. 2006, 43, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bara, J.J.; Parker, A.T.; Muturi, E.J. Comparative Susceptibility of Ochlerotatus japonicus, Ochlerotatus triseriatus, Aedes albopictus, and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) to La Crosse Virus. J. Med. Entomol. 2016, 53, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloria-Soria, A.; Brackney, D.E.; Armstrong, P.M. Saliva Collection via Capillary Method May Underestimate Arboviral Transmission by Mosquitoes. Parasites Vectors 2022, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, C.S.; Featherston, K.M.; Lin, J.; Franz, A.W.E. Detection of La Crosse Virus In Situ and in Individual Progeny to Assess the Vertical Transmission Potential in Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti. Insects 2023, 14, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhold, J.M.; Lazzari, C.R.; Lahondère, C. Effects of the Environmental Temperature on Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus Mosquitoes: A Review. Insects 2018, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denlinger, D.L.; Armbruster, P.A. Mosquito Diapause. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2014, 59, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bova, J.E. Overwintering Mechanisms of La Crosse Virus Vectors; Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S.N.; López, K.; Coutermash-Ott, S.; Auguste, D.I.; Porier, D.L.; Armstrong, P.M.; Andreadis, T.G.; Eastwood, G.; Auguste, A.J. La Crosse Virus Shows Strain-Specific Differences in Pathogenesis. Pathogens 2021, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Faw, L.R.; Armstrong, P.M.; Paulson, S.L.; Eastwood, G. Contrasting La Crosse Virus Lineage III Vector Competency in Two Geographical Populations of Aedes triseriatus and Aedes albopictus Mosquitoes. Biology 2025, 14, 1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121771

Faw LR, Armstrong PM, Paulson SL, Eastwood G. Contrasting La Crosse Virus Lineage III Vector Competency in Two Geographical Populations of Aedes triseriatus and Aedes albopictus Mosquitoes. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121771

Chicago/Turabian StyleFaw, Lindsey R., Philip M. Armstrong, Sally L. Paulson, and Gillian Eastwood. 2025. "Contrasting La Crosse Virus Lineage III Vector Competency in Two Geographical Populations of Aedes triseriatus and Aedes albopictus Mosquitoes" Biology 14, no. 12: 1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121771

APA StyleFaw, L. R., Armstrong, P. M., Paulson, S. L., & Eastwood, G. (2025). Contrasting La Crosse Virus Lineage III Vector Competency in Two Geographical Populations of Aedes triseriatus and Aedes albopictus Mosquitoes. Biology, 14(12), 1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121771