The WRKY Transcription Factor GmWRKY40 Enhances Soybean Resistance to Phytophthora sojae via the Jasmonic Acid Pathway

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Cultivation and Pathogen Challenge

2.2. Soybean Hairy Root Transformation

2.3. QRT-PCR

2.4. Subcellular Localization of GmWRKY40

2.5. RNA-seq and Metabolome Analysis

2.6. Quantification of Jasmonic Acid (JA)

2.7. ChIP Assays

2.8. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

2.9. Y2H Assay

2.10. BiFC Assay

2.11. SLCA

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Expression and Subcellular Localization of the Soybean Transcription Factor GmWRKY40

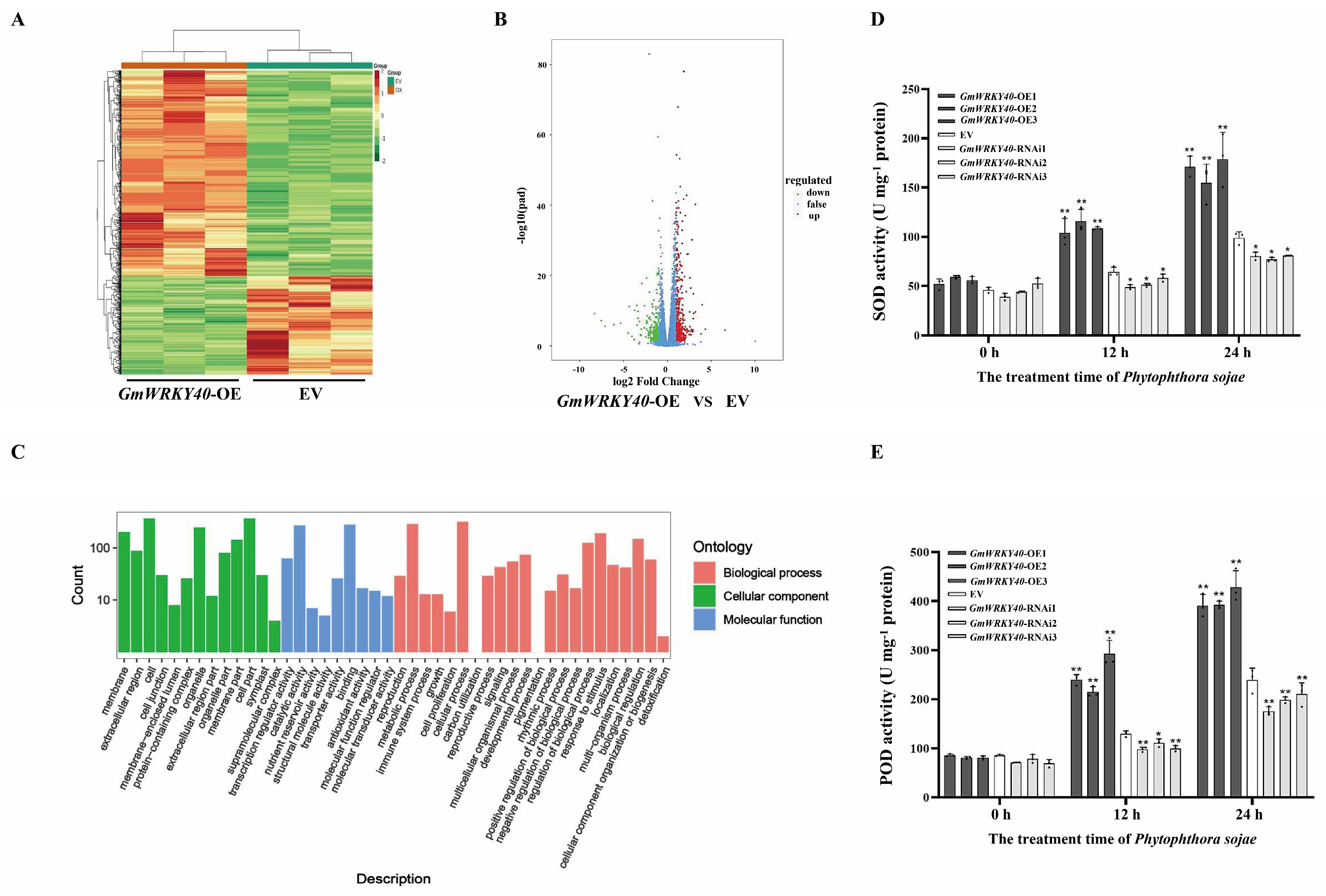

3.2. GmWRKY40 Enhances the Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes in Response to P. sojae Infection

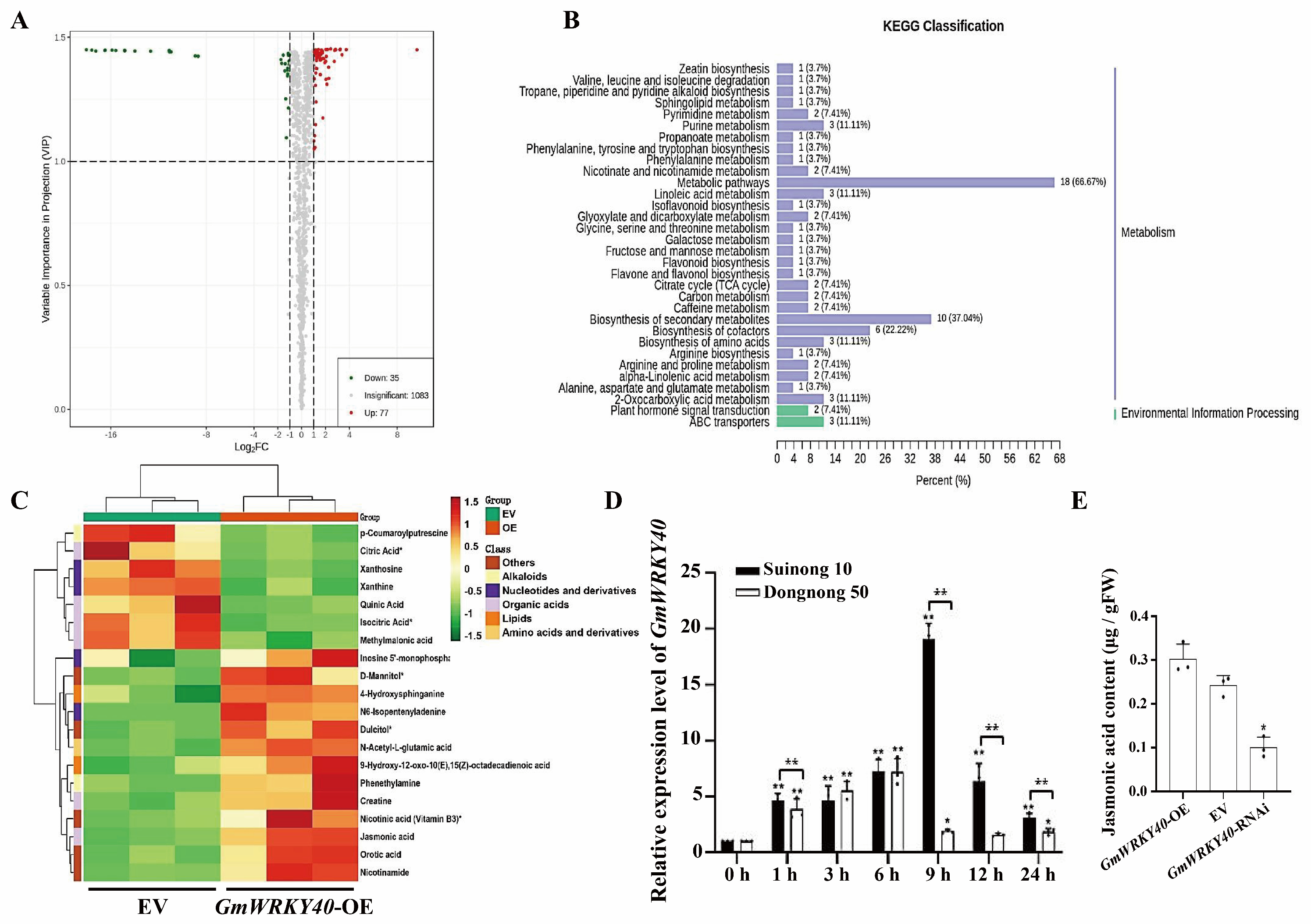

3.3. Metabolomic Analysis Reveals the Involvement of GmWRKY40 in the Jasmonic Acid Pathway

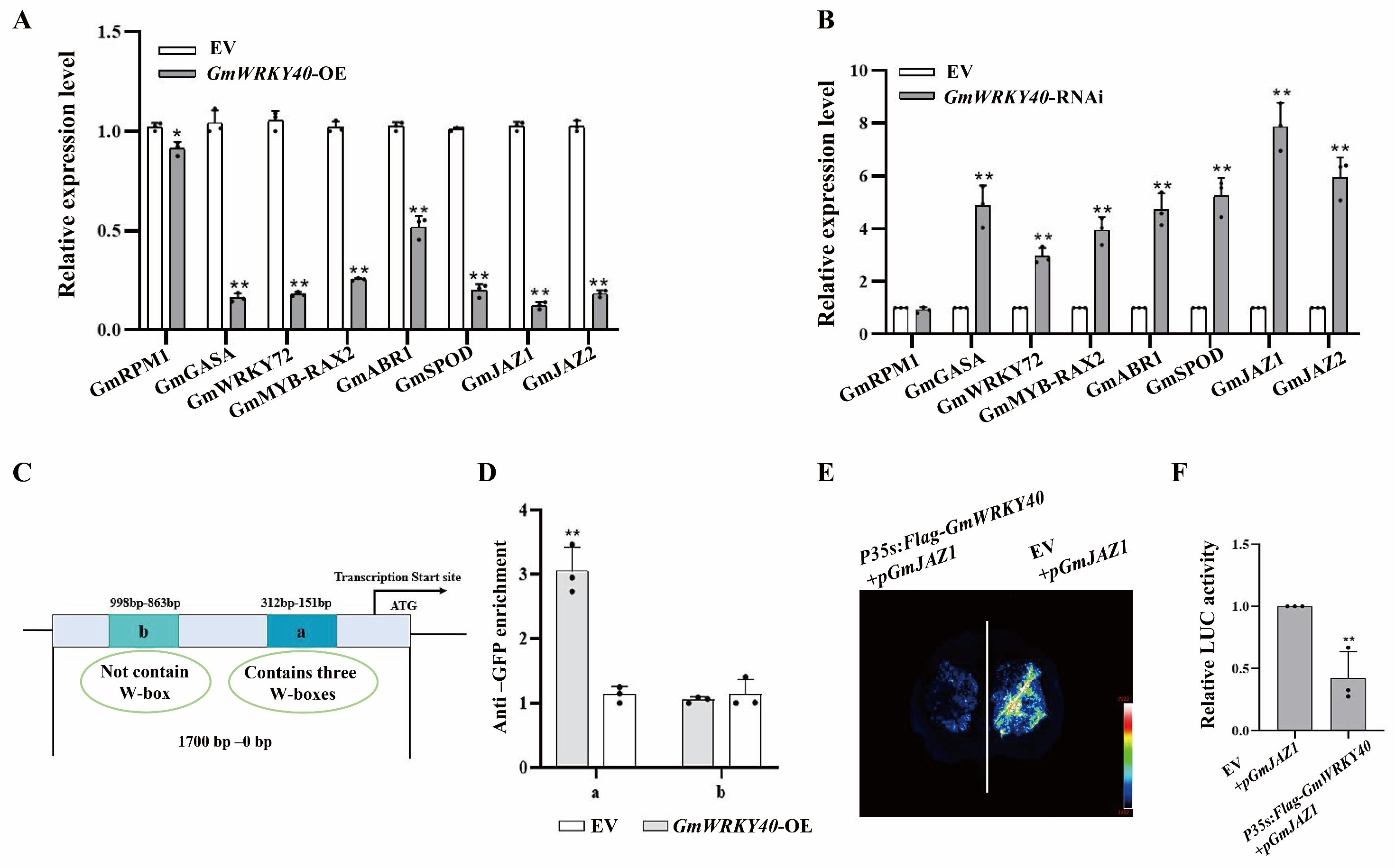

3.4. GmWRKY40 Regulates the Transcription of GmJAZ1

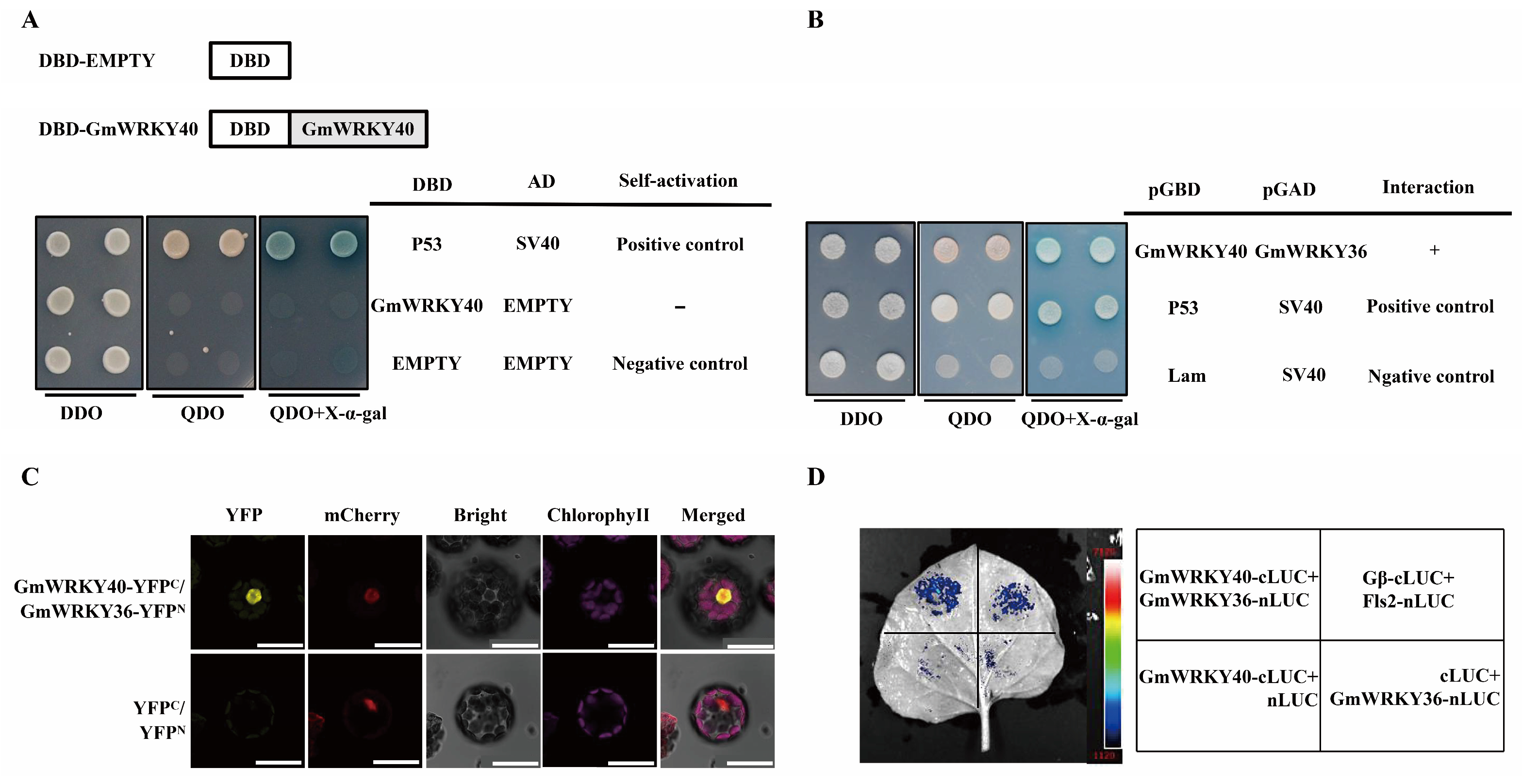

3.5. GmWRKY40 Interacts with GmWRKY36

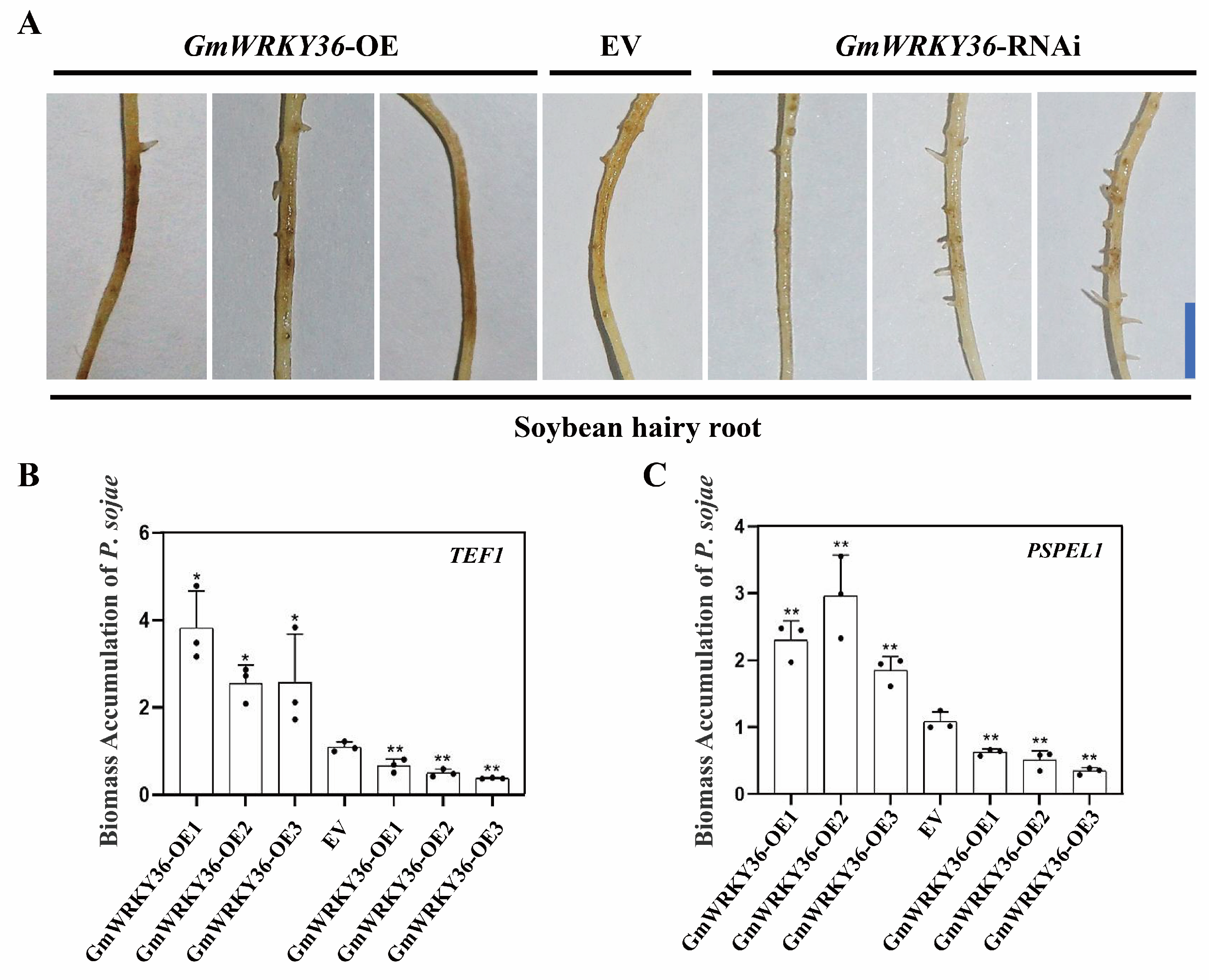

3.6. GmWRKY36 Promotes Soybean Susceptibility to P. sojae

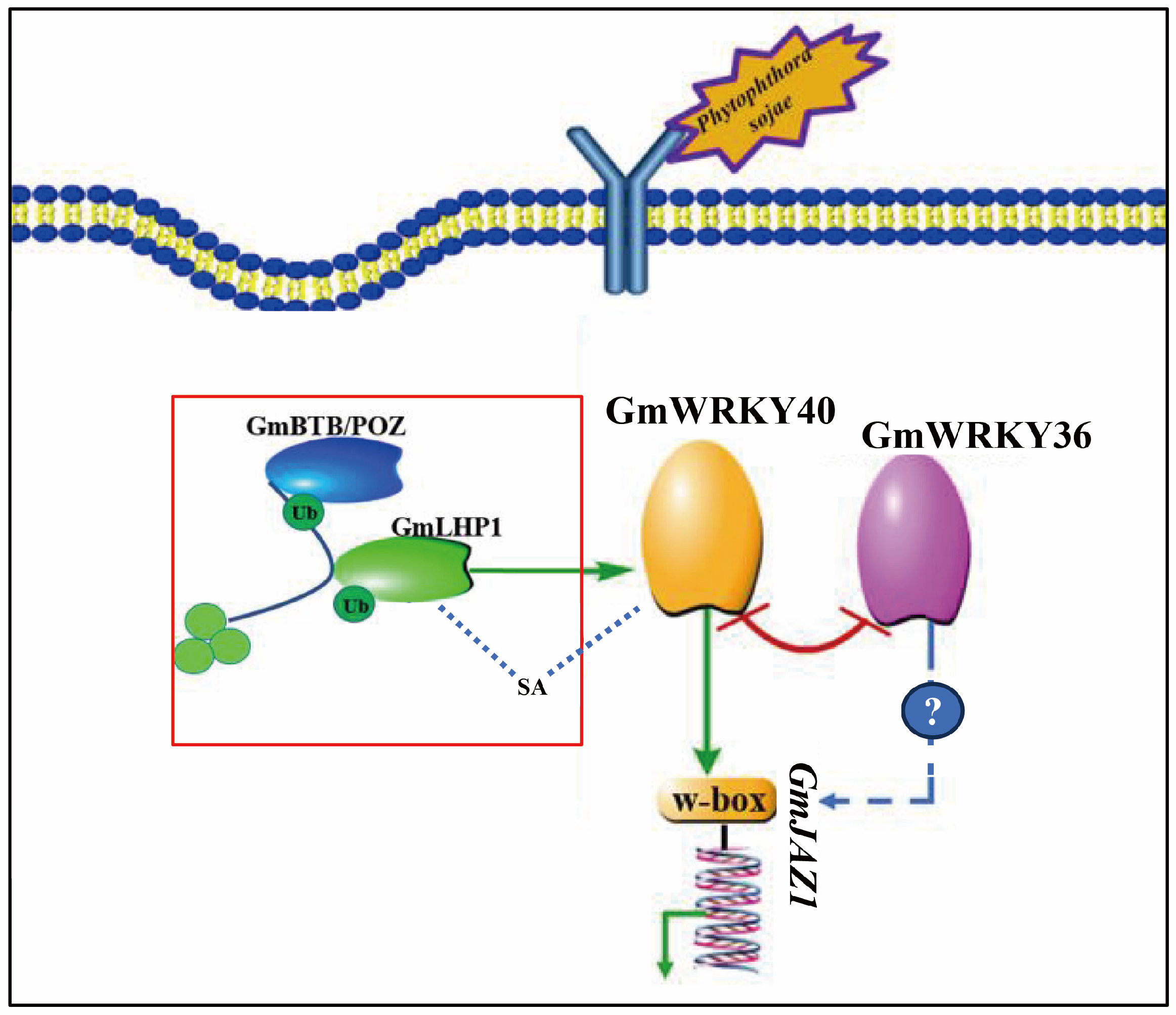

4. Discussion

4.1. GmWRKY40 Promotes Soybean Defense Against P. sojae

4.2. GmWRKY40 Activates the JA Signaling Pathway via Direct Transcriptional Repression of GmJAZ1

4.3. GmWRKY40 Forms an Antagonistic Module with the Negative Regulator GmWRKY36

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, J.D.G.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Lin, M.; Qiu, M.; Kong, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ye, W.; Dong, S.; He, S. Chitin synthase is involved in vegetative growth, asexual reproduction and pathogenesis of Phytophthora capsici and Phytophthora sojae. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 4537–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourelis, J.; van der Hoorn, R.A.L. Defended to the nines: 25 years of resistance gene cloning identifies nine mechanisms for R protein function. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, S. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in signaling plant growth and development. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Guo, J.; Zhou, X.; Bai, X.; Azeem, M.; Zhu, L.; Chen, L.; Chu, M.; Wang, H. Integrative transcriptome analysis of mRNA and miRNA in pepper’s response to Phytophthora capsici infection. Biology 2024, 13, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, M.; Van Oosten, V.; Van Poecke, R.; Van Pelt, J.; Pozo, M.; Mueller, M.; Buchala, A.; Métraux, J.; Van Loon, L.; Dicke, M.; et al. Signal signature and transcriptome changes of Arabidopsis during pathogen and insect attack. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2005, 18, 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillwig, M.S.; Chiozza, M.; Casteel, C.L.; Lau, S.T.; Hohenstein, J.; Hernandez, E.; Jander, G.; MacIntosh, G.C. Abscisic acid deficiency increases defence responses against Myzus persicae in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhu, X.; Shi, C.-M.; Xu, G.; Zuo, S.; Shi, Y.; Cao, W.; Kang, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, R.; et al. OsEIL2 balances rice immune responses against (hemi)biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens via the salicylic acid and jasmonic acid synergism. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Fei, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; He, Y. Overexpression of sly-miR398b compromises disease rsistance against Botrytis cinerea through regulating ROS homeostasis and JA-related defense genes in tomato. Plants 2023, 12, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Hu, C.; Zhu, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xia, X.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.; H.Foyer, C.; Yu, J. The MYC2-PUB22-JAZ4 module plays a crucial role in jasmonate signaling in tomato. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thines, B.; Katsir, L.; Melotto, M.; Niu, Y.; Mandaokar, A.; Liu, G.; Nomura, K.; He, S.Y.; Howe, G.A.; Browse, J. JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCFCO11 complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature 2007, 448, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-B.; Bokowiec, M.T.; Rushton, P.J.; Han, S.-C.; Timko, M.R. Tobacco transcription factors NtMYC2a and NtMYC2b form nuclear complexes with the NtJAZ1 repressor and regulate multiple jasmonate-inducible steps in nicotine biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngou, B.P.M.; Ahn, H.-K.; Ding, P.; Jones, J.D.G. Mutual potentiation of plant immunity by cell-surface and intracellular receptors. Nature 2021, 592, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. The WRKY transcription factor superfamily: Its origin in eukaryotes and expansion in plants. BMC Evol. Biol. 2005, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Xu, Z.; Chen, M.; Yu, D. Functions of WRKYs in plant growth and development. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 630–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xia, P. WRKY transcription factors: Key regulators in plant drought tolerance. Plant Sci. 2025, 359, 112647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Jiang, Y.; Peng, J.; Guo, J.; Lin, M.; Jin, C.; Huang, J.; Tang, W.; Guan, D.; He, S. The transcriptional reprograming and functional identification of WRKY family members in pepper’s response to Phytophthora capsici infection. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, S.; Nakamura, K. Characterization of a cDNA encoding a novel DNA-binding protein, SPF1, that recognizes SP8 sequences in the 5′ upstream regions of genes coding for sporamin and β-amylase from sweet potato. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1994, 244, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Bai, X.; Liu, L.; Ma, X.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Gong, B. CaWRKY01-10 and CaWRKY08-4 confer pepper’s resistance to Phytophthora capsici infection by directly activating a cluster of defense-related genes. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 11682–11693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, X. WRKY transcription factors in response to metal stress in plants: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, J.; Li, M.; Chang, M.; Xu, K.; Shang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Palmer, I.; Zhang, Y.; McGill, J.; et al. A bacterial type III effector targets the master regulator of salicylic acid signaling, NPR1, to subvert plant immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrant, W.E.; Dong, X. Systemic acquired resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2004, 42, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, D.; Xiao, J.; Ding, X.; Xiong, M.; Cai, M.; Cao, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, C.; Wang, S. OsWRKY13 mediates rice disease resistance by regulating defense-related genes in salicylate- and jasmonate-dependent signaling. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Z.; Liu, H.; Qiu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, C.; Wang, S. A Pair of allelic WRKY genes play opposite roles in rice-bacteria interactions. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, T.; Chen, Y.; Dai, M.; Yu, S.; Xu, L.; Su, Y.; et al. Expression characteristics and functional analysis of the ScWRKY3 gene from sugarcane. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, J.; Qu, C.; Mo, X.; Zhang, X. Genome-Wide identification of WRKY in suaeda australis against salt stress. Forests 2024, 15, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Yin, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, J.; Tan, X.; Wu, L. WRKY transcription factors participate in abiotic stress responses mediated by sugar metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1646357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Jiang, L.; Du, B.; Ning, B.; Ding, X.; Zhang, C.; Song, B.; Liu, S.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Y.; et al. GmMKK4-activated GmMPK6 stimulates GmERF113 to trigger resistance to Phytophthora sojae in soybean. Plant J. 2022, 111, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, S. OsVQ1 links rice immunity and flowering via interaction with a mitogen-activated protein kinase OsMPK6. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1989–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, J.; Li, J.; Li, R.; Ye, M.; Kuai, P.; Zhang, T.; Lou, Y. The transcription factor OsWRKY45 negatively modulates the resistance of rice to the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, H.; Gao, H.; Fang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, M.; Wei, W.; Song, B.; Liu, S.; et al. GmBTB/POZ promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of LHP1 to regulate the response of soybean to Phytophthora sojae. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, P.; Wu, J.; Xue, A.G.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Chen, C.; Chen, W.; Lv, H. Races of Phytophthora sojae and their virulences on soybean cultivars in Heilongjiang, China. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, T.L.; Graham, M.Y.; Subramanian, S.; Yu, O. RNAi silencing of genes for elicitation or biosynthesis of 5-deoxyisoflavonoids suppresses race-specific resistance and hypersensitive cell death in Phytophthora sojae infected tissues. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.D.; Cho, Y.H.; Sheen, J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: A versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1565–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Xi, D.H.; Deng, X.G.; Peng, X.J.; Tang, H.; Chen, Y.J.; Jian, W.; Feng, H.; Lin, H.H. The chilli veinal mottle virus regulates expression of the tobacco mosaic virus resistance gene N. and jasmonic acid/ethylene signaling is essential for systemic resistance against chilli veinal mottle virus in tobacco. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 32, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.; Alvarez-Venegas, R.; Avramova, Z. An efficient chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) protocol for studying histone modifications in Arabidopsis plants. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xu, J.; He, Y.; Yang, K.Y.; Mordorski, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S. Phosphorylation of an ERF transcription factor by Arabidopsis MPK3/MPK6 regulates plant defense gene induction and fungal resistance. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 1126–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eulgem, T.; Rushton, P.J.; Robatzek, S.; Somssich, I.E. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.J.; Dong, L.D.; Han, D.; Zhang, F.; Wu, J.J.; Jiang, L.Y.; Cheng, Q.; Li, R.P.; Lu, W.C.; Meng, F.S.; et al. GmWRKY31 and GmHDL56 enhances resistance to Phytophthora sojae by regulating defense-related gene expression in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.-S.; Zheng, J.-C.; Jin, Z.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Huang, H.; Chen, L.-G. Possible correlation between high temperature-induced floret sterility and endogenous levels of IAA, GAs and ABA in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Growth Regul. 2008, 54, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengiste, T.; Liao, C.-J. Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens, 20 years later: What has changed? Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2025, 63, 279–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Xiao, Z.; Cai, H.; Wang, C.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, L.; Yang, S.; Liu, Z. A novel leucine-rich repeat protein, CaLRR51, acts as a positive regulator in the response of pepper to Ralstonia solanacearum infection. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 18, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquoz, J.L.; Buchala, A.J.; Meuwly, P.H.; Metraux, J.P. Arachidonic acid induces local but not systemic synthesis of salicylic acid and confers systemic resistance in potato plants to Phytophthora infestans and Alternaria solani. Phytopathology 1995, 85, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Ying, J.; Ye, Y.; Wen, S.; Qian, R. Green light induces Solanum lycopersicum JA synthesis and inhibits Botrytis cinerea infection cushion formation to resist grey mould disease. Physiol. Plant 2025, 177, e70156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Zhu, M.; Alariqi, M.; Hussian, A.; Ma, W.; Lindsey, K.; Zhang, X.; et al. Cotton bollworm (H. armigera) effector PPI5 targets FKBP17-2 to inhibit ER immunity and JA/SA responses, enhancing insect feeding. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2407826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.H.; Huang, B.; Zheng, X.; Liang, K.; Wang, G.L.; Sun, X. The WRKY10-VQ8 module safely and effectively regulates rice thermotolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 2126–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metabolite | Formula | Index | Class I |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jasmonic acid | C12H18O3 | pme1654 | Organic acids |

| 5’-Glucosyloxyjasmanic acid | C18H28O9 | Lmzn001582 | Phenolic acids |

| 12-Oxo-phytodienoic acid | C18H28O3 | Zmyn004548 | Lipids |

| 13(s)-hydroperoxy-(9z,11e,15z)-octadecatrienoic acid | C18H30O4 | Zmzn003953 | Lipids |

| α-Linolenic Acid | C18H30O2 | mws0367 | Lipids |

| 9-Hydroperoxy-10E,12,15Z-octadecatrienoic acid | C18H30O4 | pmb2791 | Lipids |

| Linoleic acid | C18H32O2 | mws1491 | Lipids |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, G.; Guo, F.; Sun, Y.; Fang, X.; Chen, X.; Ma, K.; Wang, X.; Li, K.; et al. The WRKY Transcription Factor GmWRKY40 Enhances Soybean Resistance to Phytophthora sojae via the Jasmonic Acid Pathway. Biology 2025, 14, 1769. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121769

Gao H, Zhang C, Zhang G, Guo F, Sun Y, Fang X, Chen X, Ma K, Wang X, Li K, et al. The WRKY Transcription Factor GmWRKY40 Enhances Soybean Resistance to Phytophthora sojae via the Jasmonic Acid Pathway. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1769. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121769

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Hong, Chuanzhong Zhang, Gengpu Zhang, Fengcai Guo, Yan Sun, Xin Fang, Xiaoyu Chen, Kexin Ma, Xiran Wang, Kexin Li, and et al. 2025. "The WRKY Transcription Factor GmWRKY40 Enhances Soybean Resistance to Phytophthora sojae via the Jasmonic Acid Pathway" Biology 14, no. 12: 1769. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121769

APA StyleGao, H., Zhang, C., Zhang, G., Guo, F., Sun, Y., Fang, X., Chen, X., Ma, K., Wang, X., Li, K., Tong, J., Wu, J., Xu, P., & Zhang, S. (2025). The WRKY Transcription Factor GmWRKY40 Enhances Soybean Resistance to Phytophthora sojae via the Jasmonic Acid Pathway. Biology, 14(12), 1769. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121769