Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Uncover the Potential of Flavonoids in Response to Saline–Alkali Stress in Codonopsis pilosula

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials, Growth Conditions, and Saline–Alkali Stress Treatments

2.2. Phenotypic Measurement

2.3. Analysis of Physiological and Biochemical Indices

2.4. Metabolome Analysis

2.5. Transcriptome Analysis and RT-qPCR Identification

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

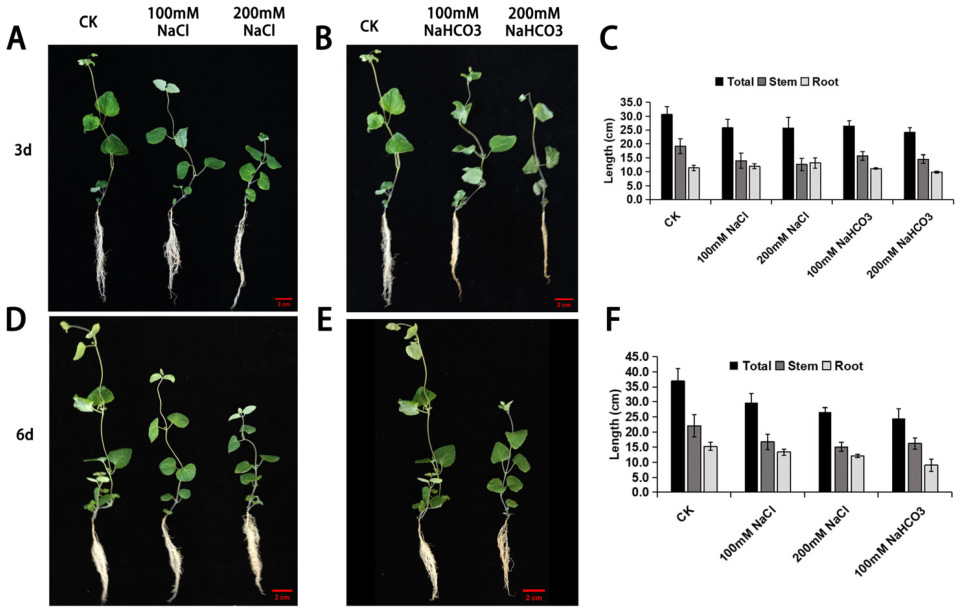

3.1. Phenotypic Observation of Cp Under Saline–Alkali Stress

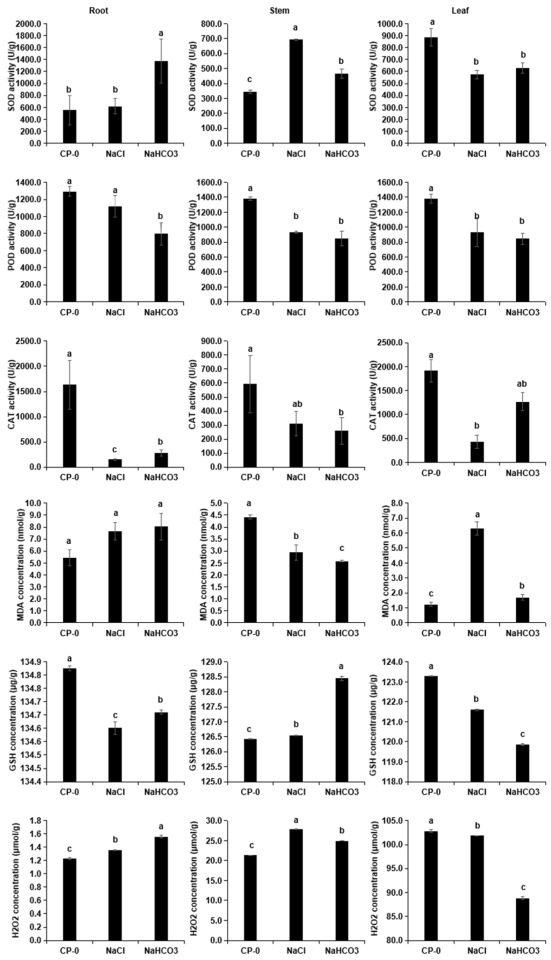

3.2. Physiological Indices: Detection of Different Cp Organs Under Saline–Alkali Stress

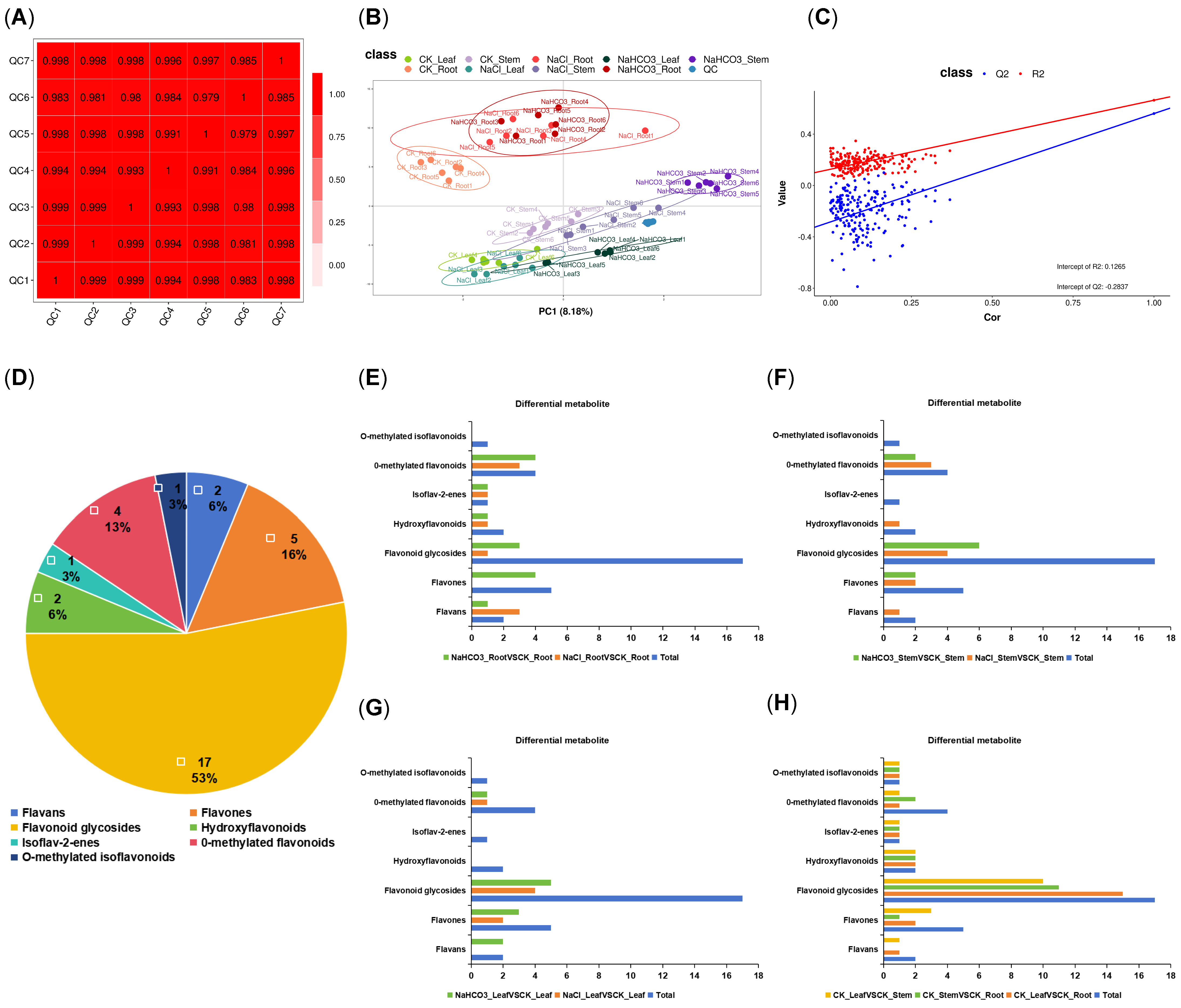

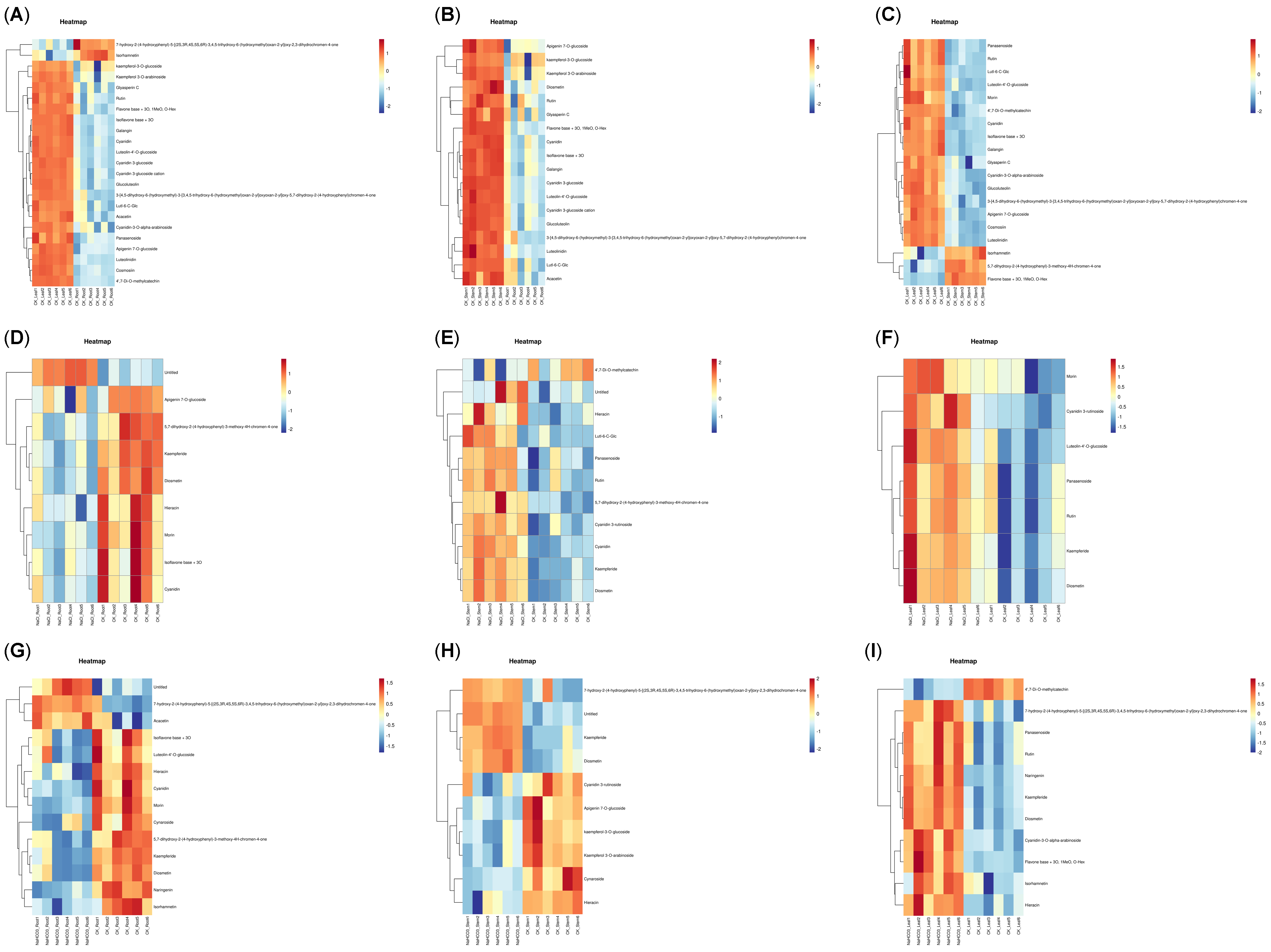

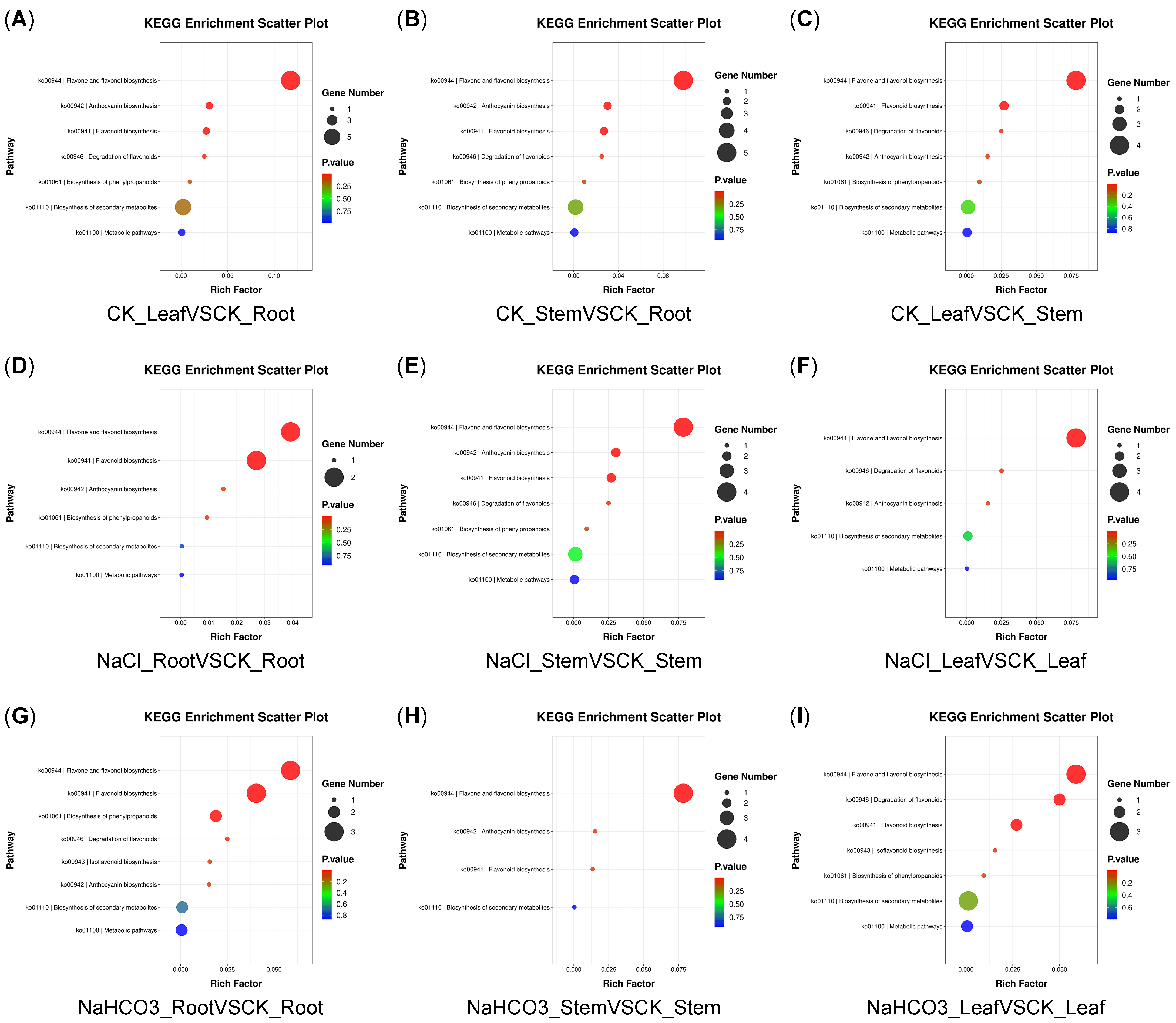

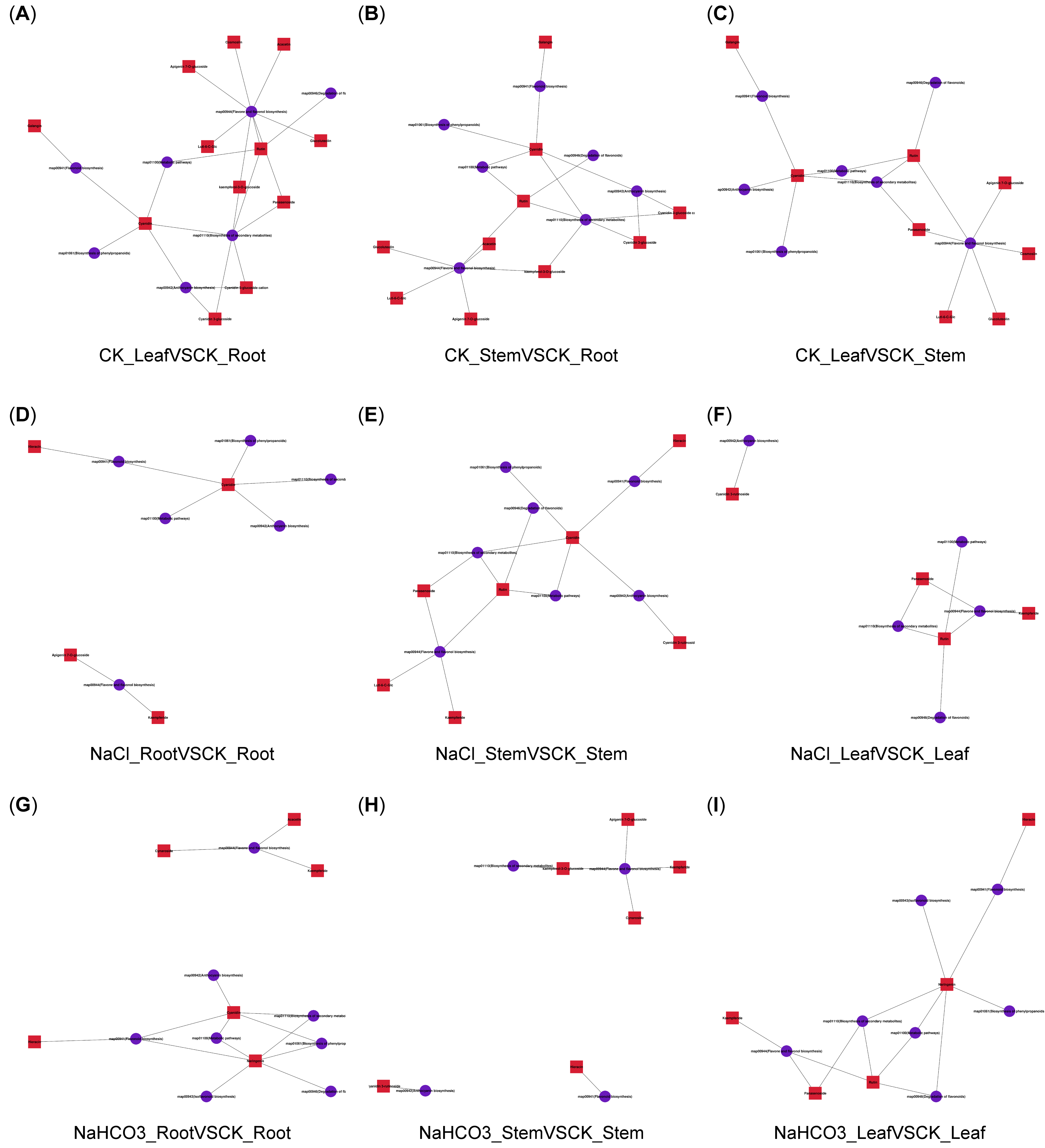

3.3. Metabolome Analysis of Different Organs of Cp Under Saline–Alkali Stress

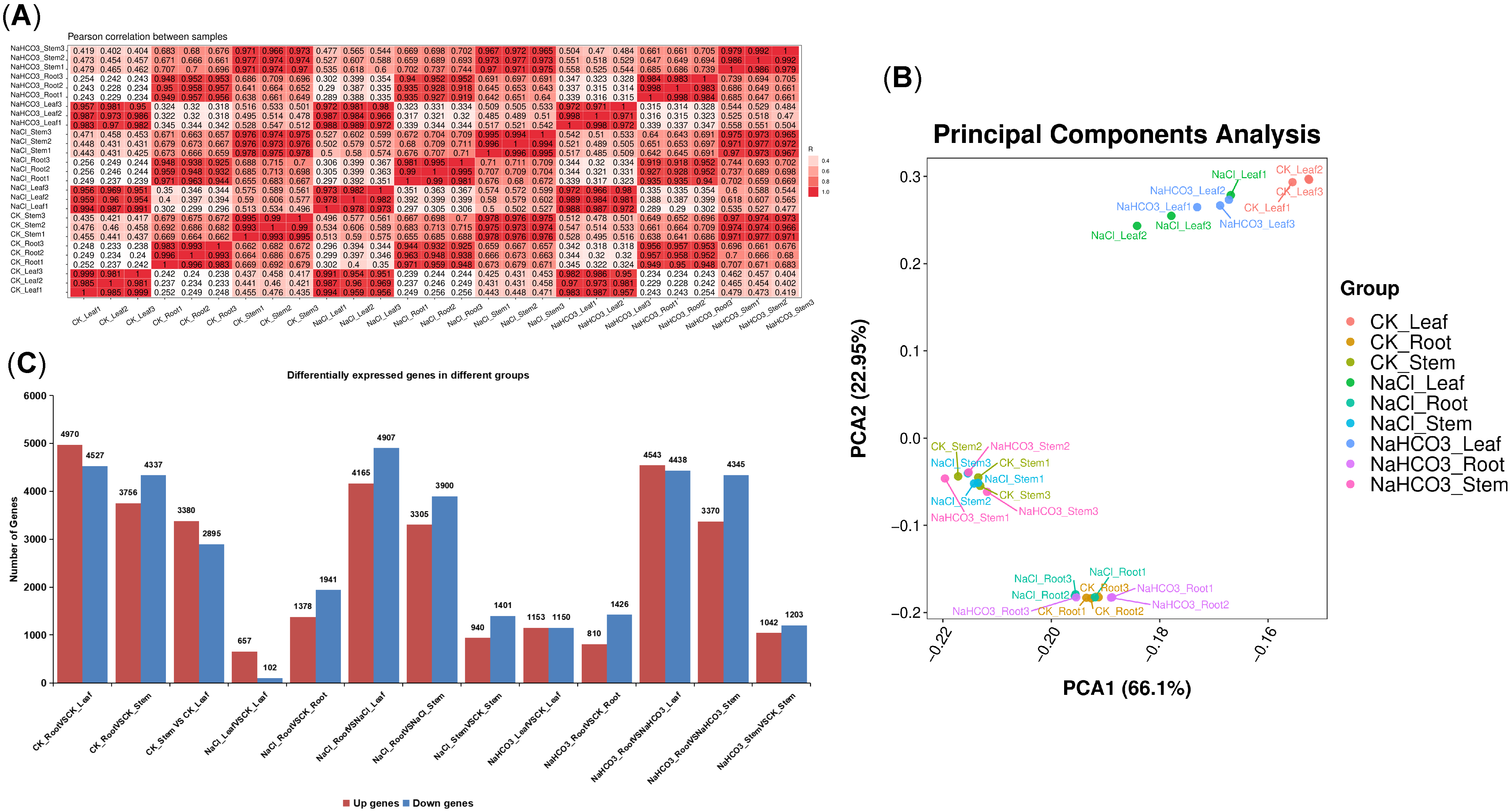

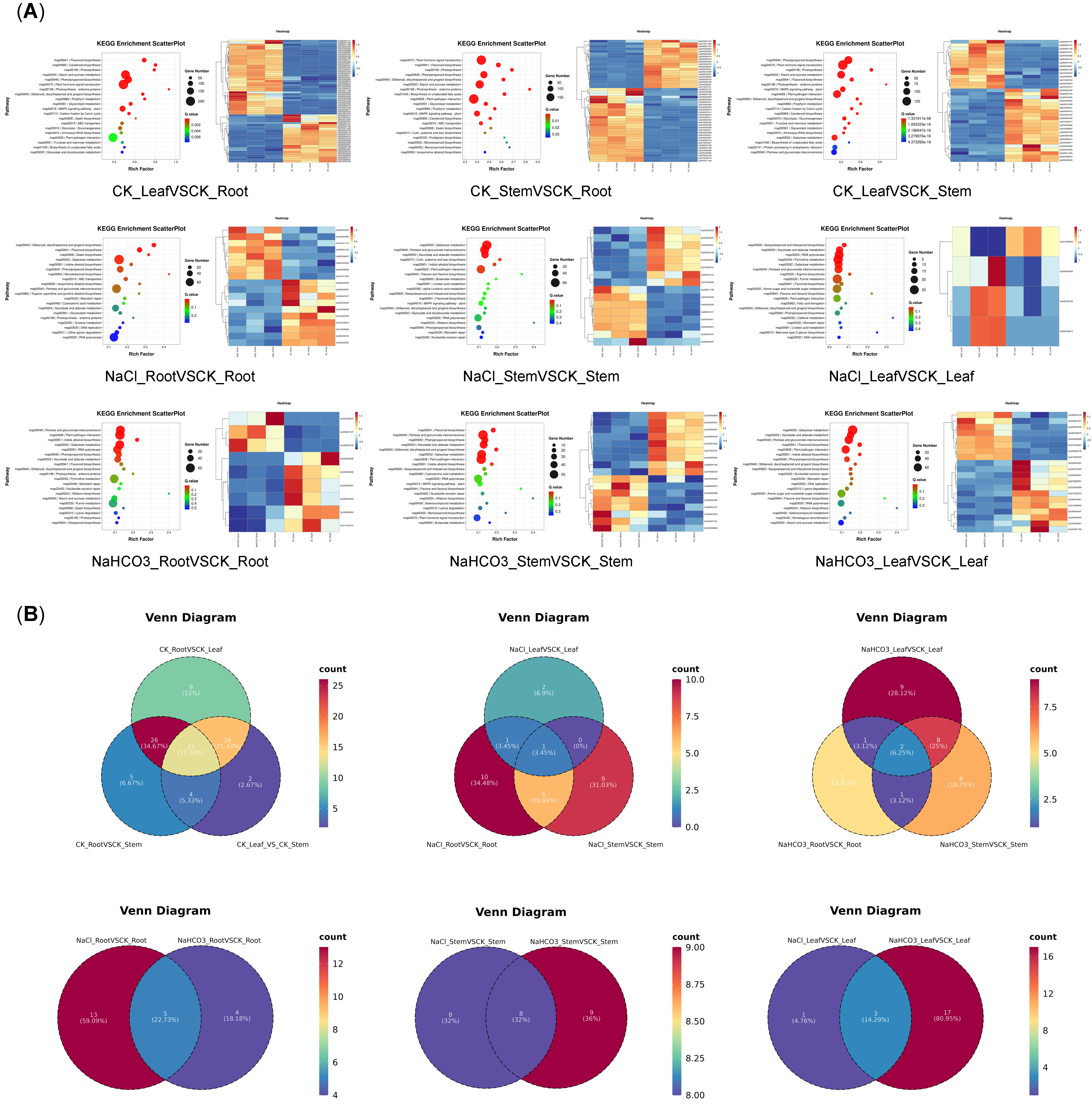

3.4. Transcriptome Analysis of Different Organs of Cp Under Saline–Alkali Stress

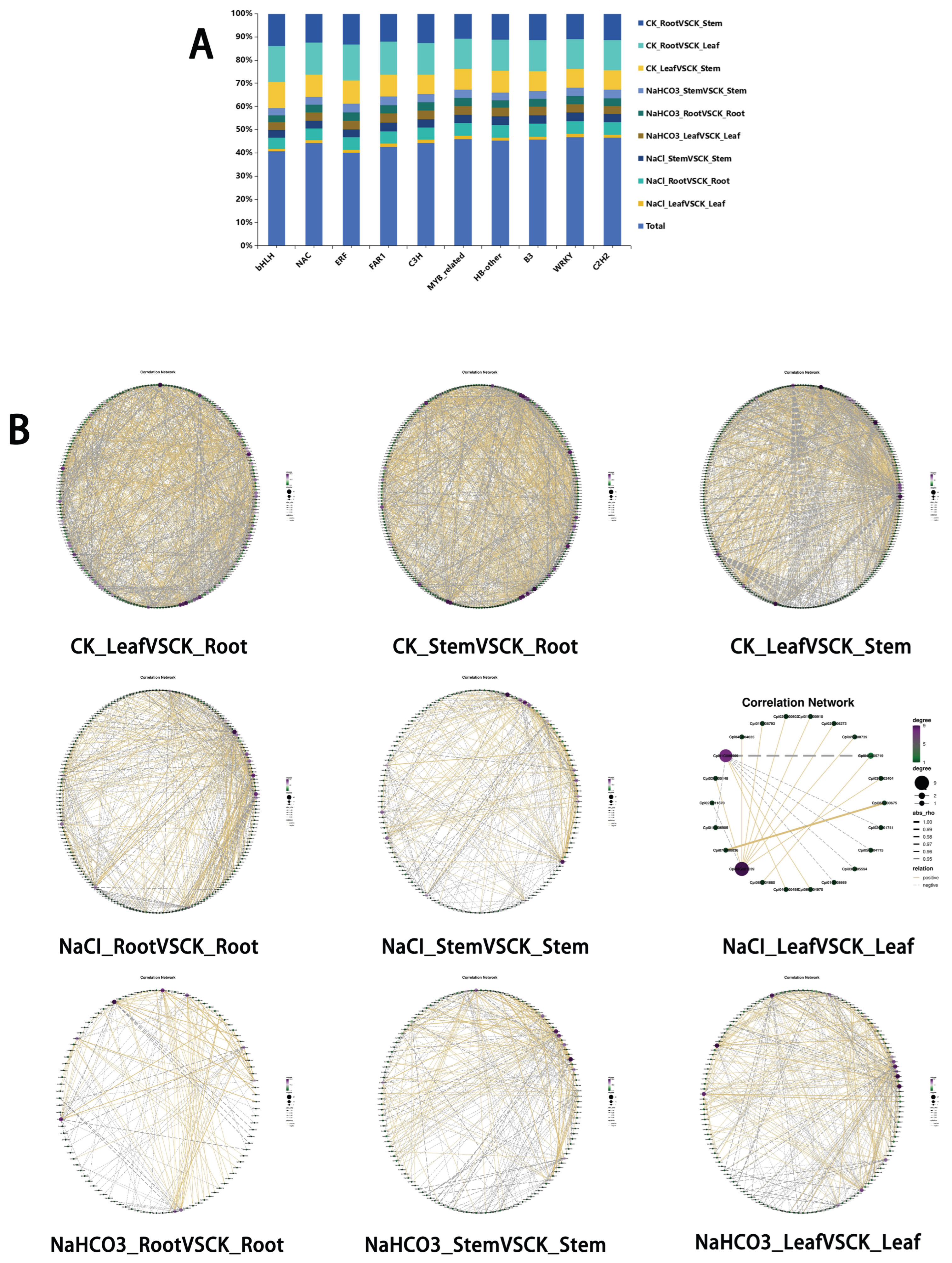

3.5. Differential Transcription Factor Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dai, R.; Zhan, N.; Geng, R.; Xu, K.; Zhou, X.; Li, L.; Yan, G.; Zhou, F.; Cai, G. Progress on Salt Tolerance in Brassica napus. Plants 2024, 13, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, S.; Hou, X.; Liang, X. Response Mechanisms of Plants Under Saline-Alkali Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 667458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karak, P. Biological activities of flavonoids: An overview. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2019, 10, 1567–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, H.; Slika, H.; Nasser, S.; Pintus, G.; Khachab, M.; Sahebkar, A.; Eid, A.H. Flavonoids, gut microbiota and cardiovascular disease: Dynamics and interplay. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 209, 107452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, X.; Guo, J. Physiological and transcriptomic analyses of yellow horn (Xanthoceras sorbifolia) provide important insights into salt and saline-alkali stress tolerance. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Hou, H.; Ma, X.; Sun, S.; Wang, H.; Kong, L. Metabolomics and gene expression analysis reveal the accumulation patterns of phenylpropanoids and flavonoids in different colored-grain wheats (Triticum aestivum L.). Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Yan, W.; Xie, S.; Yu, J.; Yao, G.; Xia, P.; Wu, Y.; Yang, H. Physiological and Transcriptional Analysis Reveals the Response Mechanism of Camellia vietnamensis Huang to Drought Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Liu, B.; Dong, W.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Gao, C. Comparative transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses provide insights into the responses to NaCl and Cd stress in Tamarix hispida. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 884, 163889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhou, X.; Meng, J.; Xu, H.; Zhou, X. WRKY Transcription Factors Modulate the Flavonoid Pathway of Rhododendron chrysanthum Pall. Under UV-B Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Yuan, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhu, G. The transcription factor WRKY41-FLAVONOID 3′-HYDROXYLASE module fine-tunes flavonoid metabolism and cold tolerance in potato. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiaf070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Si, L.; Zhang, L.; Guo, R.; Wang, R.; Dong, H.; Guo, C. Metabolomics and transcriptomics analysis revealed the response mechanism of alfalfa to combined cold and saline-alkali stress. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2024, 119, 1900–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, H. The pharmacological effects of Codonopsis pilosula and its clinical application. Clin. Med. 2005, 25, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.M.; Wu, Z.F. Research progress of the medicinal plant Codonopsis pilosula. Ani Agric. Sci. 2009, 15, 088. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Ji, C. Advances in the Chemical Components, Pharmacological Effects and Application Research of Codon pilosula Used as Food and Medicine. Food Sci. 2024, 45, 338–348. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Wang, H. Regulation of gene expression in different tissues of Codonopsis under drought stress based on transcriptome sequencing analysis. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2022, 53, 4465–4475. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Wang, S.; Qin, J.; Zhang, G.; Na, X.; Wang, X.; Bi, Y. Integrated Physiological, Transcriptomic, and Metabolomic Analyses Revealed Molecular Mechanism for Salt Resistance in Soybean Roots. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Zhu, L.; Ma, D.; Zhang, F.; Cai, Z.; Bai, H.; Hui, J.; Li, S.; Xu, X.; Li, M. Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Highlight the Flavonoid Compounds Response to Alkaline Salt Stress in Glycyrrhiza uralensis Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 5477–5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Yang, W.; Jing, W.; Shahid, M.O.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Choisy, P.; Xu, T.; Ma, N.; Gao, J.; et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals key regulatory defense pathways and genes involved in salt tolerance of rose plants. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Inaba, M.; Yokota, A.; Murata, N. Oxidative stress inhibits the repair of photodamage to the photosynthetic machinery. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 5587–5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Long, R.; Kang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Sun, H.; Li, X.; Yang, Q. Comparative Proteomic Analysis Reveals That Antioxidant System and Soluble Sugar Metabolism Contribute to Salt Tolerance in Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) Leaves. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Ghalami, R.Z.; Kamran, M.; Van Breusegem, F.; Karpiński, S. To Be or Not to Be? Are Reactive Oxygen Species, Antioxidants, and Stress Signalling Universal Determinants of Life or Death? Cells 2022, 11, 4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Lou, X.; Zhang, W.; Xu, T.; Tang, M. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Enhanced Drought Resistance of Populus cathayana by Regulating the 14-3-3 Family Protein Genes. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0245621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Teng, J.; Ma, L.; Tong, H.; Ren, B.; Wang, L.; Li, W. Flavonoids Isolated from the Flowers of Limonium bicolor and their In Vitro Antitumor Evaluation. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2017, 13, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezayian, M.; Niknam, V.; Ebrahimzadeh, H. Oxidative damage and antioxidative system in algae. Toxicol. Rep. 2019, 6, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, R.; Arzani, A.; Mirmohammady Maibody, S.A.M. Polyphenols, Flavonoids, and Antioxidant Activity Involved in Salt Tolerance in Wheat, Aegilops cylindrica and Their Amphidiploids. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 646221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Guan, Q.; Dong, R.; Ran, K.; Wang, H.; Dong, X.; Wei, S. Metabolomics Analysis of Phenolic Composition and Content in Five Pear Cultivars Leaves. Plants 2024, 13, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Gao, R.; Wang, Y.; An, Z.; Tian, Y.; Wan, H.; Wei, D.; Wang, F.; et al. Lonicera caerulea genome reveals molecular mechanisms of freezing tolerance and anthocyanin biosynthesis. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 24, 615. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Dong, B.; Song, Z.; Qi, M.; Chen, T.; Du, T.; Cao, H.; Liu, N.; Meng, D.; Yang, Q.; et al. Molecular mechanism of naringenin regulation on flavonoid biosynthesis to improve the salt tolerance in pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan (Linn.) Millsp.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 196, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, T.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Sun, Y.; Ni, Y.; Guo, Y. Enhancing sweet sorghum emergence and stress resilience in saline-alkaline soils through ABA seed priming: Insights into hormonal and metabolic reprogramming. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, L.; Miao, Y.; Zeng, T.; Jiang, Y.; Pei, J.; Ahmad, B.; Huang, L. Metabolome profiling and molecular docking analysis revealed the metabolic differences and potential pharmacological mechanisms of the inflorescence and succulent stem of Cistanche deserticola. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 27226–27245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Cui, M.; Hao, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, W.; Xue, A.; Chingin, K.; Luo, L. In Situ Study of Metabolic Response of Arabidopsis thaliana Leaves to Salt Stress by Neutral Desorption-Extractive Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 12945–12952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, W.; Xu, J.; Sun, H.; Zhong, J.; Gu, Y.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of flavonoid accumulation in germinating common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) under salt stress. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 928805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, V.; Umar, S.; Iqbal, N. Synergistic action of Pseudomonas fluorescens with melatonin attenuates salt toxicity in mustard by regulating antioxidant system and flavonoid profile. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e14092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbulis, I.E.; Winkel-Shirley, B. Interactions among enzymes of the Arabidopsis flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 12929–12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhuang, F.; Wang, J.; Gao, R.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Fang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Revealed a Comprehensive Understanding of the Biochemical and Genetic Mechanisms Underlying the Color Variations in Chrysanthemums. Metabolites 2023, 13, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, X. Overexpression Analysis of PtrLBD41 Suggests Its Involvement in Salt Tolerance and Flavonoid Pathway in Populus trichocarpa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Leng, Z.; Qi, F.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, W.; Liu, K.; Zhang, C.; et al. Evaluating the Differential Response of Transcription Factors in Diploid versus Autotetraploid Rice Leaves Subjected to Diverse Saline-Alkali Stresses. Genes 2023, 14, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Meng, R.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Lu, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, Z. Preliminary Analysis of the Salt-Tolerance Mechanisms of Different Varieties of Dandelion (Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz.) Under Salt Stress. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Han, W.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, X.; He, J.; Kong, M.; Huo, Q.; Lv, G. Physiological and transcriptomic analysis reveals the coating of microcapsules embedded with bacteria can enhance wheat salt tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Ying, J.; Ye, Y.; Cai, Y.; Qian, R. Comprehensive transcriptome analysis of Asparagus officinalis in response to varying levels of salt stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulanov, A.N.; Andreeva, E.A.; Tsvetkova, N.V.; Zykin, P.A. Regulation of Flavonoid Biosynthesis by the MYB-bHLH-WDR (MBW) Complex in Plants and Its Specific Features in Cereals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Ren, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, S.; Yan, H.; et al. Metabolic and molecular basis of flavonoid biosynthesis in Lycii fructus: An integration of metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2025, 255, 116653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, M.; Zhao, C.; Wang, R.; Xue, L.; Lei, J. A novel bHLH transcription factor, FabHLH110, is involved in regulation of anthocyanin synthesis in petals of pink-flowered strawberry. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 222, 109713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Yang, F.; Zhou, X.; Jia, W.; Zhu, X.; Mu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mi, Z.; Zhang, S.; et al. Genome-wide identification of the bHLH gene family and the mechanism regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis by ChEGL1 in Cerasus humilis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 288, 138783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Wan, Y.; Sun, X.; Su, W.; Li, K. Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Uncover the Potential of Flavonoids in Response to Saline–Alkali Stress in Codonopsis pilosula. Biology 2025, 14, 1759. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121759

Liu J, Wan Y, Sun X, Su W, Li K. Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Uncover the Potential of Flavonoids in Response to Saline–Alkali Stress in Codonopsis pilosula. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1759. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121759

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jinhua, Yongqing Wan, Xiaowei Sun, Wenting Su, and Kaixia Li. 2025. "Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Uncover the Potential of Flavonoids in Response to Saline–Alkali Stress in Codonopsis pilosula" Biology 14, no. 12: 1759. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121759

APA StyleLiu, J., Wan, Y., Sun, X., Su, W., & Li, K. (2025). Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Uncover the Potential of Flavonoids in Response to Saline–Alkali Stress in Codonopsis pilosula. Biology, 14(12), 1759. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121759