Potentially Zoonotic Bacteria in Exotic Freshwater Turtles from the Canary Islands (Spain)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

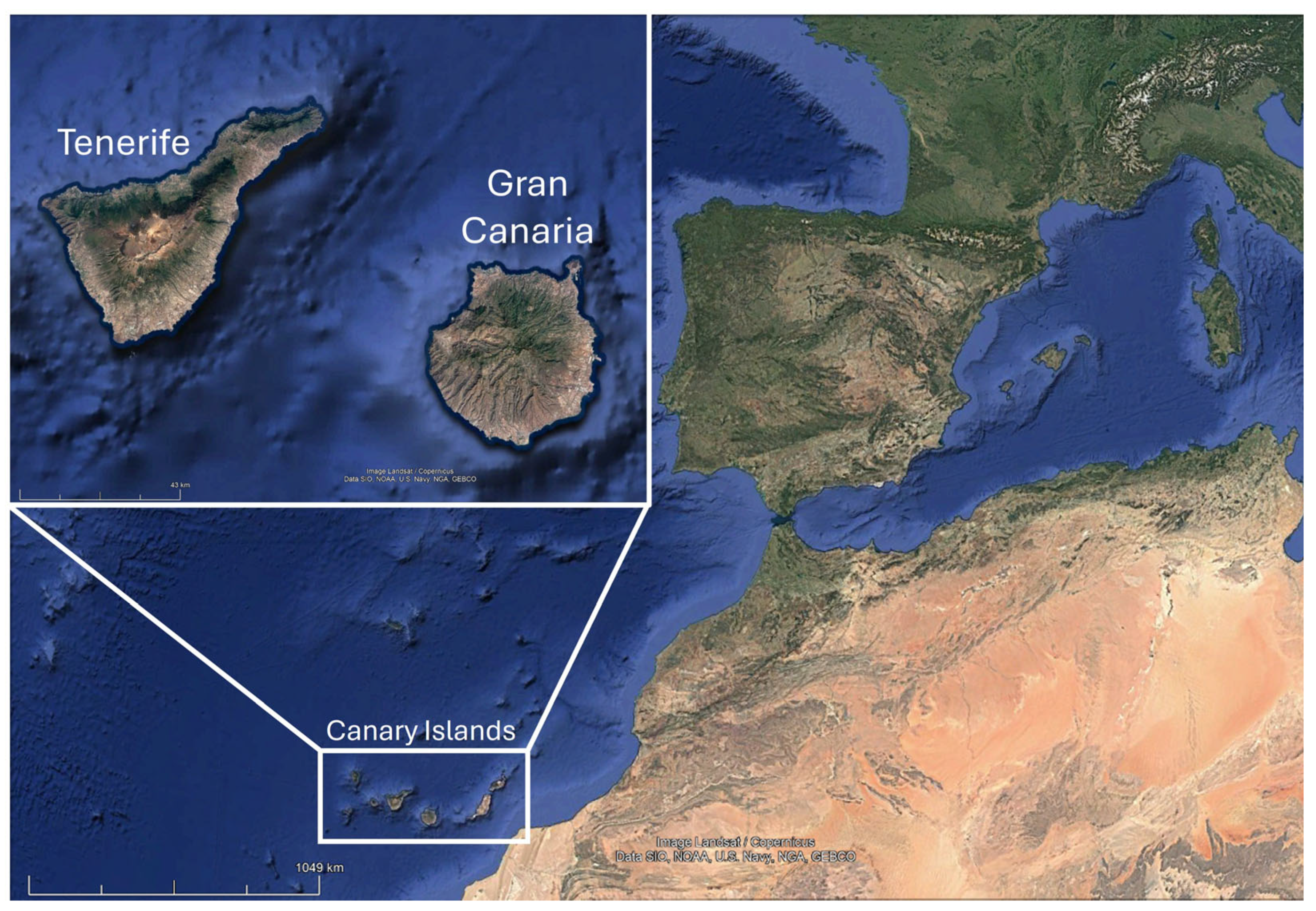

2.1. Study Area and Specimen Collection

2.2. Sampling and Bacterial Isolation

2.3. Molecular Biology Techniques

2.3.1. DNA Extraction

2.3.2. PCR Identification

2.3.3. Controls

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General

3.2. Campylobacter spp.

3.3. Escherichia coli (stx1, stx2 and Eae Genes)

3.4. Listeria monocytogenes

3.5. Mycobacterium spp.

3.6. Pseudomonas spp.

3.7. Salmonella spp.

3.8. Staphylococcus spp.

3.9. Vibrio spp.

3.10. Yersinia enterocolitica

4. Discussion

4.1. Campylobacter spp.

4.2. Escherichia coli (stx1, stx2 and Eae Genes)

4.3. Listeria monocytogenes

4.4. Mycobacterium spp.

4.5. Pseudomonas spp.

4.6. Salmonella spp.

4.7. Staphylococcus spp.

4.8. Vibrio spp.

4.9. Yersinia enterocolitica

4.10. Summary

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zoonoses. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/zoonoses (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Chomel, B.B. Zoonoses. In Encyclopedia of Microbiology, 3rd ed.; Schaechter, M., Ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Soong, L. Emerging and Re-emerging Zoonoses are Major and Global Challenges for Public Health. Zoonoses 2021, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, D.B. Emerging Infectious Diseases. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 54, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slifko, T.R.; Smith, H.V.; Rose, J.B. Emerging parasite zoonoses associated with water and food. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000, 30, 1379–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, A.R.; Baldwin, V.M.; Roy, S.; Essex-Lopresti, A.E.; Prior, J.L.; Harmer, N.J. Zoonoses under our noses. Microbes. Infect. 2019, 21, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morens, D.M.; Fauci, A.S. Emerging Pandemic Diseases: How We Got to COVID-19. Cell 2020, 182, 1077–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overgaauw, P.A.M.; Vinke, C.M.; van Hagen, M.A.E.; Lipman, L.J.A. A One Health Perspective on the Human–Companion Animal Relationship with Emphasis on Zoonotic Aspects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, R.N.; Krysko, K.L. Invasive and introduced reptiles and amphibians. In Current Therapy in Reptile Medicine and Surgery; Mader, I., Douglas, R., Drivers, S.J., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M.N.F. The concept of one health applied to the problem of zoonotic diseases. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, K.; Grudlewska-Buda, K.; Khamesipour, F. Zoonoses and emerging pathogens. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borroto-Páez, R.; Bosch, R.A.; Fabres, B.A.; García, O.A. Introduced amphibians and reptiles in the Cuban Archipelago. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 10, 985–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, R.G.; Niemiller, M.L. Island Invaders: Introduced amphibians and reptiles in the Turks and Caicos Islands. IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians 2010, 17, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit, L.A.; Croll, D.A.; Tershy, B.; Newton, K.M.; Spatz, D.R.; Holmes, N.D.; Kilpatrick, A.M. Estimating Burdens of Neglected Tropical Zoonotic Diseases on Islands with Introduced Mammals. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciencia Canaria—Invasoras: Las Especies Que Acechan en las Islas. Available online: https://www.cienciacanaria.es/secciones/a-fondo/1174-invasoras-las-especies-que-acechan-en-las-islas (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Biota. Available online: https://www.biodiversidadcanarias.es/biota/estadisticas?se=0&m=0 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Piquet, J.C.; Warren, D.L.; Saavedra Bolaños, J.F.; Sánchez Rivero, J.M.; Gallo-Barneto, R.; Cabrera-Pérez, M.A.; Fisher, R.N.; Fisher, S.R.; Rochester, C.J.; Hinds, B.; et al. Could climate change benefit invasive snakes? Modelling the potential distribution of the California Kingsnake in the Canary Islands. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 294, 112917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Hernández, K.M.; Orós, J.; Priestnall, S.L.; Monzón-Argüello, C.; Rodríguez-Ponce, E. Parasitological findings in the invasive California kingsnake (Lampropeltis californiae) in Gran Canaria, Spain. Parasitology 2021, 148, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Hernández, K.M.; Rodríguez-Ponce, E.; Medina, I.R.; Acosta-Hernández, B.; Priestnall, S.L.; Vega, S.; Marin, C.; Cerdà-Cuéllar, M.; Marco-Fuertes, A.; Ayats, T.; et al. One Health Approach: Invasive California Kingsnake (Lampropeltis californiae) as an Important Source of Antimicrobial Drug-Resistant Salmonella Clones on Gran Canaria Island. Animals 2023, 13, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- REDEXOS. Available online: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/cptss/sostenibilidad/biodiversidad/redexos/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Real Decreto 630/2013, de 2 de Agosto, Por el que se Regula el Catálogo Español de Especies Exóticas Invasoras. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 185. 3 August 2013. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2013-8565 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Standfuss, B.; Lipovšek, G.; Fritz, U.; Vamberger, M. Threat or fiction: Is the pond slider (Trachemys scripta) really invasive in Central Europe? A case study from Slovenia. Conserv. Genet. 2016, 17, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Heo, G.J. Pet-turtles: A potential source of human pathogenic bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 3785–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebani, V.V. Domestic reptiles as source of zoonotic bacteria: A mini review. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 10, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Acosta, N.; Pino-Vera, R.; Izquierdo-Rodríguez, E.; Afonso, O.; Foronda, P. Zoonotic Bacteria in Anolis sp., an Invasive Species Introduced to the Canary Islands (Spain). Animals 2023, 13, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino-Vera, R.; Abreu-Acosta, N.; Foronda, P. Study of Zoonotic Pathogens in Alien Population of Veiled Chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus) in the Canary Islands (Spain). Animals 2023, 13, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Clemente, S.; Almeida, C.; Hernández, J.C.; Brito, A.; Hernández, M. A genetic approach to the origin of Millepora sp. in the eastern Atlantic. Coral Reefs 2015, 34, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Clark, C.G.; Taylor, T.M.; Pucknell, C.; Barton, C.; Price, L.; Woodward, D.L.; Rodgers, F.G. Colony Multiplex PCR Assay for Identification and Differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, C. upsaliensis, and C. fetus subsp. fetus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 4744–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M.; Blanco, J.E.; Mora, A.; Dahbi, G.; Alonso, M.P.; González, E.A.; Bernárdez, M.I.; Blanco, J. Serotypes, virulence genes, and intimin types of shiga toxin (verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from cattle in Spain and identification of a new intimin variant gene (eae-ξ). J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaton, K.; Sahli, R.; Bille, J. Development of Polymerase Chain Reaction assays for detection of Listeria monocytogenes in clinical cerebrospinal fluid samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, 1931–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, Y.; Jeon, B.Y.; Jin, H.; Cho, S.N.; Lee, H. A simple and efficient Multiplex PCR assay for the identification of Mycobacterium genus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex to the species level. Yonsei Med. J. 2013, 54, 1220–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, D.; Lim, A., Jr.; Pirnay, J.P.; Struelens, M.; Vandenvelde, C.; Duinslaeger, L.; Vanderkelen, A.; Cornelis, P. Direct detection and identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in clinical samples such as skin biopsy specimens and expectorations by Multiplex PCR Based on two outer membrane lipoprotein genes, oprI and oprL. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 1295–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, C.G.; Santana, A.P.; da Silva, P.H.; Gonçalves, V.S.; Barros, M.A.; Torres, F.A.; Murata, L.S.; Perecmanis, S. PCR multiplex for detection of Salmonella Enteritidis, Typhi and Typhimurium and occurrence in poultry meat. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 2010, 139, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Peña, E.; Martín-Nuñez, E.; Pulido-Reyes, G.; Martín-Padrón, J.; Caro-Carrillo, E.; Donate-Correa, J.; Lorenzo-Castrillejo, I.; Alcoba-Flórez, J.; Machín, F.; Méndez-Alvarez, S. Multiplex PCR assay for identification of six different Staphylococcus spp. and simultaneous detection of methicillin and mupirocin resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 2698–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Shi, X.; Zou, G.; Wei, Q.; Sun, X. Design of Vibrio 16S rRNA gene specific primers and their application in the analysis of seawater Vibrio community. J. Ocean Univ. China 2006, 5, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neogi, S.B.; Chowdhury, N.; Asakura, M.; Hinenoya, A.; Haldar, S.; Saidi, S.M.; Kogure, K.; Lara, R.J.; Yamasaki, S. A highly sensitive and specific multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 51, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannet, W.J.B.; Reessink, M.; Brunings, H.A.; Maas, H.M.E. Detection of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica by rapid and sensitive duplex PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 4483–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimesaat, M.M.; Backert, S.; Alter, T.; Bereswill, S. Human Campylobacteriosis—A Serious Infectious Threat in a One Health Perspective. In Fighting Campylobacter Infections, Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Backert, S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masila, N.M.; Ross, K.E.; Gardner, M.G.; Whiley, H. Zoonotic and Public Health Implications of Campylobacter Species and Squamates (Lizards, Snakes and Amphisbaenians). Pathogens 2020, 9, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portes, A.B.; Panzenhagen, P.; Pereira dos Santos, A.M.; Junior, C.A.C. Antibiotic Resistance in Campylobacter: A Systematic Review of South American Isolates. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, C. Campylobacter . Clin. Lab. Med. 2015, 35, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.J.; Duim, B.; Zomer, A.L.; Wagenaar, J.A. Living in Cold Blood: Arcobacter, Campylobacter, and Helicobacter in Reptiles. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Iraola, G. Pathogenomics of Emerging Campylobacter Species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00072-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, S.J. The consequences of Campylobacter infection. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 33, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, M.; Piccirillo, A. Pet reptiles as potential reservoir of Campylobacter species with zoonotic potential. Vet. Rec. 2014, 174, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luca, C.; Iraola, G.; Apostolakos, I.; Boetto, E.; Piccirillo, A. Occurrence and diversity of Campylobacter species in captive chelonians. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 241, 108567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, C.; Ingresa-Capaccioni, S.; González-Bodi, S.; Marco-Jiménez, F.; Vega, S. Free-living turtles are a reservoir for Salmonella but not for Campylobacter. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M.J.; Kik, M.; Timmerman, A.J.; Severs, T.T.; Kusters, J.G.; Duim, B.; Wagenaar, J.A. Occurrence, diversity, and host association of intestinal Campylobacter, Arcobacter, and Helicobacter in reptiles. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenaillon, O.; Skurnik, D.; Picard, B.; Denamur, E. The population genetics of commensal Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puvača, N.; de Llanos Frutos, R. Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Humans and Pet Animals. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, L.W. Distinguishing Pathovars from Nonpathovars: Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2020, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, A.; Fleckenstein, J.M. Interactions of pathogenic Escherichia coli with CEACAMs. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1120331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Kanazaki, M.; Hata, E.; Kubo, M. Prevalence and characteristics of eae- and stx-positive strains of Escherichia coli from wild birds in the immediate environment of Tokyo Bay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 292–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombé, F.; van Hoek, A.H.A.M.; Nailis, H.; Auvray, F.; Janssen, T.; Piérard, D. Intestinal Carriage of Two Distinct stx2f-Carrying Escherichia coli Strains by a Child with Uncomplicated Diarrhea. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton-Celsa, A.R. Shiga Toxin (stx) Classification, Structure, and Function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2014, 2, EHEC-0024-2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami-Ahangaran, M.; Zia-Jahromi, N. Identification of shiga toxin and intimin genes in Escherichia coli detected from canary (Serinus canaria domestica). Toxicol. Ind. Health 2012, 30, 724–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Książczyk, M.; Dudek, B.; Kuczkowski, M.; O’Hara, R.; Korzekwa, K.; Wzorek, A.; Korzeniowska-Kowal, A.; Upton, M.; Junka, A.; Wieliczko, A.; et al. The Phylogenetic Structure of Reptile, Avian and Uropathogenic Escherichia coli with Particular Reference to Extraintestinal Pathotypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dec, M.; Stepien-Pysniak, D.; Szczepaniak, K.; Turchi, B.; Urban-Chmiel, R. Virulence Profiles and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Escherichia coli Strains from Pet Reptiles. Pathogens 2022, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, R.; Sánchez, S.; Alonso, J.M.; Herrera-León, S.; Rey, J.; Echeita, M.A.; Morán, J.M.; García-Sánchez, A. Salmonella spp. and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli prevalence in an ocellated lizard (Timon lepidus) research center in Spain. Foodborne. Pathog. Dis. 2011, 8, 1309–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Trujillo, G.U.; Gutiérrez-Miceli, F.A.; Mandujano-García, L.; Oliva-Llaven, M.A.; Ibarra-Martínez, C.; Mendoza-Nazar, P.; Ruiz-Sesma, B.; Tejeda-Cruz, C.; Pérez-Vázquez, L.C.; Pérez-Batrez, J.E.; et al. Captive green iguana carries diarrheagenic Escherichia coli pathotypes. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disson, O.; Moura, A.; Lecuit, M. Making sense of the biodiversity and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Trends. Microbiol. 2021, 29, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamon, M.; Bierne, H.; Cossart, P. Listeria monocytogenes: A multifaceted model. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, C.L.; Ramachandran, A.; Allison, R.W.; Wall, C.R.; Dieterly, A.M.; Brandão, J. Listeria monocytogenes in an inland bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). J. Exot. Pet Med. 2019, 30, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubini, S.; Baruffaldi, M.; Taddei, R.; D’Annunzio, G.; Scaltriti, E.; Tambassi, M.; Menozzi, I.; Bondesan, G.; Mazzariol, S.; Centelleghe, C.; et al. Loggerhead Sea Turtle as Possible Source of Transmission for Zoonotic Listeriosis in the Marine Environment. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Orsi, R.H.; Chen, R.; Gunderson, M.; Roof, S.; Wiedmann, M.; Childs-Sanford, S.E.; Cummings, K.J. Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from wildlife in central New York. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakiewicz, A.; Ziółkowska, G.; Zięba, P.; Dziedzic, B.M.; Gnat, S.; Wójcik, M.; Dziedzic, R.; Kostruba, A. Aerobic bacterial microbiota isolated from the cloaca of the European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis) in Poland. J. Wildl. Dis. 2015, 51, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalaswamy, R.; Shanmugam, S.; Mondal, R.; Subbian, S. Of tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections—A comparative analysis of epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reil, I.; Špičić, S.; Kompes, G.; Duvnjak, S.; Zdelar-Tuk, M.; Stojević, D.; Cvetnić, Z. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in captive and pet reptiles. Acta Vet. Brno 2017, 86, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, L.S.; das Neves Dias-Neto, R.; Cagnini, D.Q.; Yamatogi, R.S.; Oliveira-Filho, J.P.; Nemer, V.; Teixeira, R.H.; Biondo, A.W.; Araújo, J.P., Jr. Mycobacterium genavense infection in two species of captive snakes. J Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 18, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.A. Mycobacterial infections in reptiles. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2012, 15, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulski, Ł.; Krajewska-Wędzina, M.; Lipiec, M.; Weiner, M.; Zabost, A.; Augustynowicz-Kopeć, E. Mycobacterial Infections in Invasive Turtle Species in Poland. Pathogens 2023, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubry, A.; Mougari, F.; Reibel, F.; Cambau, E. Mycobacterium marinum . Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, R.; Iwasawa, M.T.; Ohkusu, K.; Kambe, N.; Matsue, H. Maximum growth temperature test for cutaneous Mycobacterium chelonae predicts the efficacy of thermal therapy. J. Dermatol. 2012, 39, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delghandi, M.R.; El-Matbouli, M.; Menanteau-Ledouble, S. Mycobacteriosis and Infections with Non-tuberculous Mycobacteria in Aquatic Organisms: A Review. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebani, V.V. Bacterial Infections in Sea Turtles. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silby, M.W.; Winstanley, C.; Godfrey, S.A.; Levy, S.B.; Jackson, R.W. Pseudomonas genomes: Diverse and adaptable. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 652–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggle, S.P.; Whiteley, M. Microbe Profile: Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Opportunistic pathogen and lab rat. Microbiology 2020, 166, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieto, S.; Rojas-Gätjens, D.; Jiménez, J.I.; Chavarría, M. The potential of Pseudomonas for bioremediation of oxyanions. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2021, 13, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, L.R.; Isabella, V.M.; Lewis, K. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms in Disease. Microb. Ecol. 2014, 68, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbaugh, K.P. Genomic complexity and plasticity ensure Pseudomonas success. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 356, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; de Sousa, T.; Silva, C.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Urine of Small Companion Animals in Global Context: Comprehensive Analysis. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Roldán, L.; Rojo-Bezares, B.; de Toro, M.; López, M.; Toledano, P.; Lozano, C.; Chichón, G.; Alvarez-Erviti, L.; Torres, C.; Sáenz, Y. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence of Pseudomonas spp. among healthy animals: Concern about exolysin ExlA detection. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 11667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, M.; Giacopello, C.; Fisichella, V.; Latella, G. Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates From Captive Reptiles. J. Exot. Pet Med. 2013, 22, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, T.S.; Garcias, B.; Castellanos, G.; Seminati, C.; Molina-López, R.A.; Darwich, L. Occurrence of multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria and resistance genes in semi-aquatic wildlife—Trachemys scripta, Neovison vison and Lutra lutra—as sentinels of environmental health. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 15, 154814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Ibarra, E.; Molina-López, R.A.; Durán, I.; Garcias, B.; Martín, M.; Darwich, L. Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria Isolated from Exotic Pets: The Situation in the Iberian Peninsula. Animals 2022, 12, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebani, V.V.; Fratini, F.; Ampola, M.; Rizzo, E.; Cerri, D.; Andreani, E. Pseudomonas and Aeromonas isolates from domestic reptiles and study of their antimicrobial in vitro sensitivity. Vet. Res. Commun. 2008, 32, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, S.; Hofacre, C.L.; Lee, M.D.; Maurer, J.J.; Doyle, M.P. Animal sources of salmonellosis in humans. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2002, 221, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinyemi, K.O.; Ajoseh, S.O.; Fakorede, C.O. A systemic review of literatures on human Salmonella enterica serovars in Nigeria (1999–2018). J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 15, 1222–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzel, A.; Desai, P.T.; Goren, A.; Schorr, Y.I.; Nissan, I.; Porwollik, S.; Valinsky, L.; McClelland, M.; Rahav, G.; Gal-Mor, O. Persistent Infections by Nontyphoidal Salmonella in Humans: Epidemiology and Genetics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; McDermott, P.F.; White, D.G.; Qaiyumi, S.; Friedman, S.L.; Abbott, J.W.; Glenn, A.; Ayers, S.L.; Post, K.W.; Fales, W.H.; et al. Characterization of multidrug resistant Salmonella recovered from diseased animals. Vet. Microbiol. 2007, 123, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland, A.M.; Sandvik, L.M.; Skarstein, M.M.; Svendal, L.; Debenham, J.J. Prevalence of Salmonella serovars isolated from reptiles in Norwegian zoos. Acta Vet. Scand. 2020, 62, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepps Keeney, C.M.; Petritz, O.A. Zoonotic Gastroenteric Diseases of Exotic Animals. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2025, 28, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Vila, J.; Díaz-Paniagua, C.; de Frutos-Escobar, C.; Jiménez-Martínez, C.; Pérez-Santigosa, N. Salmonella in free living terrestrial and aquatic turtles. Vet. Microbiol. 2007, 119, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Vila, J.; Díaz-Paniagua, C.; Pérez-Santigosa, N.; de Frutos-Escobar, C.; Herrero-Herrero, A. Salmonella in free-living exotic and native turtles and in pet exotic turtles from SW Spain. Res. Vet. Sci. 2008, 85, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, C.; Martín-Maldonado, B.; Cerdà-Cuéllar, M.; Sevilla-Navarro, S.; Lorenzo-Rebenaque, L.; Montoro-Dasi, L.; Manzanares, A.; Ayats, T.; Mencía-Gutiérrez, A.; Jordá, J.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistant Salmonella in Chelonians: Assessing Its Potential Risk in Zoological Institutions in Spain. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, D.S.; Shin, G.W.; Wendt, M.; Heo, G.J. Prevalence of Salmonella spp. in pet turtles and their environment. Lab. Anim. Res. 2016, 32, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colon, V.A.; Lugsomya, K.; Lam, H.K.; Wahl, L.C.; Parkes, R.S.V.; Cormack, C.A.; Horlbog, J.A.; Stevens, M.; Stephan, R.; Magouras, I. Serotype Diversity and Antimicrobial Resistance Profile of Salmonella enterica Isolates from Freshwater Turtles Sold for Human Consumption in Wet Markets in Hong Kong. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 912693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hydeskov, H.B.; Guardabassi, L.; Aalbaek, B.; Olsen, K.E.; Nielsen, S.S.; Bertelsen, M.F. Salmonella prevalence among reptiles in a zoo education setting. Zoonoses Public Health 2013, 60, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroki, T.; Ishihara, T.; Nakajima, N.; Furukawa, I.; Une, Y. Prevalence of Salmonella enterica Subspecies enterica in Red-Eared Sliders Trachemys scripta elegans Retailed in Pet Shops in Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 72, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, C.; Lorenzo-Rebenaque, L.; Laso, O.; Villora-Gonzalez, J.; Vega, S. Pet Reptiles: A Potential Source of Transmission of Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 613718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougan, G.; Baker, S. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and the pathogenesis of typhoid fever. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 68, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanò, S. Mechanisms of Salmonella Typhi Host Restriction. In Biophysics of Infection; Leake, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowska-Łysiak, K.; Lauterbach, R.; Międzobrodzki, J.; Kosecka-Strojek, M. Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus Bloodstream Infections in Humans: A Review. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taii, N.A.; Al-Gburi, N.M.; Khalil, N.K. Detection of biofilm formation and antibiotics resistance of Staphylococcus spp. isolated from humans’ and birds’ oral cavities. Open Vet. J. 2024, 14, 2215–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, J.A. Staphylococci: Evolving Genomes. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad-Mansour, N.; Loubet, P.; Pouget, C.; Dunyach-Remy, C.; Sotto, A.; Lavigne, J.-P.; Molle, V. Staphylococcus aureus Toxins: An Update on Their Pathogenic Properties and Potential Treatments. Toxins 2021, 13, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebani, V.V. Staphylococci, Reptiles, Amphibians, and Humans: What Are Their Relations? Pathogens 2024, 13, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strompfová, V.; Štempelová, L.; Bujňáková, D.; Karahutová, L.; Nagyová, M.; Siegfried, L. Virulence determinants and antibiotic resistance in staphylococci isolated from the skin of captive bred reptiles. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmann, M.; Aupperle-Lellbach, H.; Gentil, M.; Heusinger, A.; Müller, E.; Marschang, R.E.; Michael Pees, M. Challenges in microbiological identification of aerobic bacteria isolated from the skin of reptiles. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Gongora, C.; Chrobak, D.; Moodley, A.; Bertelsen, M.F.; Guardabassi, L. Occurrence and distribution of Staphylococcus aureus lineages among zoo animals. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 158, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida Santana, J.; Almeida Silva, B.; Borges Trevizani, N.A.; Araújo e Souza, A.M.; Nunes de Lima, G.M.; Martins Furtado, N.R.; Faria Lobato, F.C.; Silveira Silva, R.O. Isolation and antimicrobial resistance of coagulase-negative staphylococci recovered from healthy tortoises in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Cienc. Rural 2022, 52, e20210354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severn, M.M.; Williams, M.R.; Shahbandi, A.; Bunch, Z.L.; Lyon, L.M.; Nguyen, A.; Zaramela, L.S.; Todd, D.A.; Zengler, K.; Cech, N.B.; et al. The Ubiquitous Human Skin Commensal Staphylococcus hominis Protects against Opportunistic Pathogens. MBio 2022, 13, e0093022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, O.; Hurst, J.; Alkayali, T.; Schmalzle, S.A. Staphylococcus hominis cellulitis and bacteremia associated with surgical clips. IDCases 2022, 27, e01436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Tabassum, N.; Anand, R.; Kim, Y.M. Motility of Vibrio spp.: Regulation and controlling strategies. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8187–8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorian, P.; Hoque, M.M.; Espinoza-Vergara, G.; McDougald, D. Environmental Reservoirs of Pathogenic Vibrio spp. and Their Role in Disease: The List Keeps Expanding. In Vibrio spp. Infections. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Almagro-Moreno, S., Pukatzki, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennari, M.; Ghidini, V.; Caburlotto, G.; Lleo, M.M. Virulence genes and pathogenicity islands in environmental Vibrio strains nonpathogenic to humans. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 82, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, F.L.; Iida, T.; Swings, J. Biodiversity of vibrios. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004, 68, 403–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almagro-Moreno, S.; Martinez-Urtaza, J.; Pukatzki, S. Vibrio Infections and the Twenty-First Century. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1404, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froelich, B.A.; Daines, D.A. In hot water: Effects of climate change on Vibrio-human interactions. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 4101–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onohuean, H.; Agwu, E.; Nwodo, U. A Global Perspective of Vibrio Species and Associated Diseases: Three-Decade Meta-Synthesis of Research Advancement. Environ. Health Insights 2022, 16, 11786302221099406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.A.; Chang, C.C.; Li, T.H. Antimicrobial-resistance profiles of gram-negative bacteria isolated from green turtles (Chelonia mydas) in Taiwan. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 277, 116870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnino, S.; Colin, P.; Dei-Cas, E.; Madsen, M.; McLauchlin, J.; Nöckler, K.; Maradona, M.P.; Tsigarida, E.; Vanopdenbosch, E.; Van Peteghem, C. Biological risks associated with consumption of reptile products. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 2009, 134, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delli Paoli Carini, A.; Ariel, E.; Picard, J.; Elliott, L. Antibiotic Resistant Bacterial Isolates from Captive Green Turtles and In Vitro Sensitivity to Bacteriophages. Int. J. Microbiol. 2017, 2017, 5798161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuen-Im, T.; Suriyant, D.; Sawetsuwannakun, K.; Kitkumthorn, N. The Occurrence of Vibrionaceae, Staphylococcaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae in Green Turtle Chelonia mydas Rearing Seawater. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 2019, 31, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala-Norzagaray, A.A.; Aguirre, A.A.; Velazquez-Roman, J.; Flores-Villaseñor, H.; León-Sicairos, N.; Ley-Quiñonez, C.P.; Hernández-Díaz, L.J.; Canizalez-Roman, A. Isolation, characterization, and antibiotic resistance of Vibrio spp. in sea turtles from Northwestern Mexico. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancerz-Kisiel, A.; Szweda, W. Yersiniosis—Zoonotic foodborne disease of relevance to public health. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2015, 22, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fàbrega, A.; Vila, J. Yersinia enterocolitica: Pathogenesis, virulence and antimicrobial resistance. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2012, 30, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peruzy, M.F.; Aponte, M.; Proroga, Y.T.R.; Capuano, F.; Cristiano, D.; Delibato, E.; Houf, K.; Murru, N. Yersinia enterocolitica detection in pork products: Evaluation of isolation protocols. Food Microbiol. 2020, 92, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabaugh, J.A.; Anderson, D.M. Pathogenicity and virulence of Yersinia. Virulence 2024, 15, 2316439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, D.R.; Milan, C.; Ferrasso, M.M.; Dias, P.A.; Moraes, T.P.; Bandarra, P.M.; Minello, L.F.; Timm, C.D. Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli, Salmonella spp. e Yersinia enterocolitica isoladas de animais silvestres em um centro de reabilitação. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2018, 38, 1838–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, V.K. Enterobacteria of emerging pathogenic significance from clinical cases in man and animals and detection of toads and wall lizards as their reservoirs. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1978, 44, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISTAC|Hogares Según Tipos y Frecuencia de Actividades o Instalaciones Contaminantes. Islas de Canarias. 2022|Banco de datos. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

| Location | Gran Canaria | Tenerife | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | ||||

| Graptemys pseudogeographica | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Mauremys spp. | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Trachemys scripta | 17 | 13 | 30 | |

| Total | 22 | 20 | 42 | |

| Bacteria | Turtle Species | +/n (Prevalence; 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter spp.; n = 42 | Graptemys pseudogeographica | 0/2 |

| Mauremys spp. | 0/7 | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 1/3 (33.3%; 0.8–90.6) | |

| Trachemys scripta | 3/30 (10.0%; 2.1–26.5) | |

| Total | 4/42 (9.5%; 2.7–22.6) | |

| Escherichia coli (stx1, stx2 and eae genes); n = 42 | Graptemys pseudogeographica | 1/2 (50.0%; 1.26–98.7) |

| Mauremys spp. | 3/7 (42.9%; 9.9–81.6) | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 0/3 | |

| Trachemys scripta | 10/30 (33.3%; 17.3–52.9) | |

| Total | 14/42 (33.3%; 19.6–49.5) | |

| Listeria monocytogenes; n = 36 | Graptemys pseudogeographica | 0/2 |

| Mauremys spp. | 0/6 | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 0/3 | |

| Trachemys scripta | 0/25 | |

| Total | 0/36 | |

| Mycobacterium spp.; n = 19 | Graptemys pseudogeographica | – |

| Mauremys spp. | 1/2 (50.0%; 1.26–98.7) | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 1/1 (100%; 2.5–100) | |

| Trachemys scripta | 9/16 (56.3%; 29.9–80.2) | |

| Total | 11/19 (57.9%; 33.5–79.7) | |

| Pseudomonas spp.; n = 19 | Graptemys pseudogeographica | – |

| Mauremys spp. | 0/2 | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 0/1 | |

| Trachemys scripta | 2/16 (12.5%; 1.6–38.3) | |

| Total | 2/19 (10.5%; 1.3–33.1) | |

| Salmonella spp.; n = 42 | Graptemys pseudogeographica | 0/2 |

| Mauremys spp. | 1/7 (14.3%; 0.4–57.9) | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 3/3 (100%; 29.2–100) | |

| Trachemys scripta | 9/30 (30.0%; 14.7–49.4) | |

| Total | 13/42 (31.0%; 17.6–47.1) | |

| Staphylococcus spp.; n = 42 | Graptemys pseudogeographica | 1/2 (50.0%; 1.3–98.7) |

| Mauremys spp. | 1/7 (14.3%; 0.4–57.9) | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 1/3 (33.3%; 0.8–90.6) | |

| Trachemys scripta | 6/30 (20.0%; 7.7–38.6) | |

| Total | 9/42 (21.4%; 10.3–36.8) | |

| Vibrio spp.; n = 36 | Graptemys pseudogeographica | 0/2 |

| Mauremys spp. | 0/7 | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 1/3 (33.3%; 0.8–90.6) | |

| Trachemys scripta | 1/30 (3.3%; 0.1–17.2) | |

| Total | 2/36 (5.6%; 0.7–18.7) | |

| Yersinia enterocolitica; n = 19 | Graptemys pseudogeographica | – |

| Mauremys spp. | 1/2 (50.0%; 1.3–98.7) | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 1/1 (100%; 2.5–100) | |

| T. scripta | 6/16 (40.0%; 16.3–67.7) | |

| Total | 8/19 (37.5%; 15.2–64.6) |

| Turtle Species | Graptemys pseudogeographica (n = 2) | Mauremys spp. (n = 7) | Pseudemys peinsularis (n = 3) | Trachemys scripta (n = 30) | Total (n = 42) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virulence Genes | ||||||

| eae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (20.0%; 7.7–38.6) | 6 (14.3%; 5.4–28.5) | |

| stx1 | 0 | 1 (14.3%; 0.4–57.9) | 0 | 3 (12.0%; 2.5–31.2) | 4 (9.5%; 2.7–22.6) | |

| stx2 | 1 (50%; 1.3–98.7) | 2 (28.6%; 3.7–71.0) | 0 | 4 (16.0%; 4.5–36.1) | 7 (16.7%; 7.0–31.4) | |

| Total | 1 (50%; 1.3–98.7) | 3 (42.9%; 9.9–81.6) | 0 | 10 (43.3%; 25.4–62.6) | 17 (40.5%; 25.6–56.7) | |

| Island | Gran Canaria (n = 5) | Tenerife (n = 14) | Total (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turtle Species | ||||

| Graptemys pseudogeographica | – | – | – | |

| Mauremys spp. | – | 1/2 (50.0%; 1.3–98.7) | 1/2 (50.0%; 1.3 -98.7) | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 1/1 (100%; 2.5–100) | – | 1/1 (100%; 2.5–100) | |

| Trachemys scripta | 2/4 (50.0%; 6.8–93.2) | 7/12 (58.3%; 27.7–84.8) | 9/16 (56.3%; 29.9–80.2) | |

| Total | 3/5 (60.0%; 14.7–94.7) | 8/14 (57.1%; 28.9–82.3) | 11/19 (57.9%; 33.5–79.7) | |

| Island | Gran Canaria (n = 26) | Tenerife (n = 16) | Total (n = 42) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turtle Species | ||||

| Graptemys pseudogeographica | 0/2 | 0 | 0/2 | |

| Mauremys spp. | 0/4 | 1/3 (33.3%; 0.08–90.6) | 1/7 (14.3%; 0.4–57.9) | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 3/3 (100%; 29.2–100) | 0 | 3/3 (100%; 29.2–100) | |

| Trachemys scripta | 7/17 (41.2%; 18.4–67.1) | 2/13 (15.4%; 1.9–45.4) | 9/30 (30.0%; 14.7–49.4) | |

| Total | 10/26 (38.5%; 20.2–59.4) | 3/16 (18.8%; 4.0–45.6) | 13/42 (31.0%; 17.6–47.1) | |

| Island | Gran Canaria (n = 26) | Tenerife (n = 16) | Total (n = 42) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turtle Species | ||||

| Graptemys pseudogeographica | 1/2 (50.0% 1.3–98.7) | 0 | 1/2 (50.0% 1.3–98.7) | |

| Mauremys spp. | 1/4 (25.0%; 0.6–80.6) | 0/3 | 1/7 (14.3%; 0.4–57.9) | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 1/3 (33.3%; 0.8–90.6) | 0 | 1/3 (33.3%; 0.8–90.6) | |

| Trachemys scripta | 4/17 (23.5%; 6.8–49.9) | 2/13 (15.4%; 1.9–45.4) | 6/30 (20.0%; 7.7–38.6) | |

| Total | 7/26 (26.9%; 11.6–47.8) | 2/16 (12.5%; 1.6–38.3) | 9/42 (21.4%; 10.3–36.8) | |

| Island | Gran Canaria (n = 5) | Tenerife (n = 14) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turtle Species | ||||

| Graptemys pseudogeographica | – | – | – | |

| Mauremys spp. | – | 1/2 (50.0%; 1.3–98.7) | 1/2 (50.0%; 1.3–98.7) | |

| Pseudemys peninsularis | 1/1 (100%; 2.5–100) | – | 1/1 (100%; 2.5–100) | |

| Trachemys scripta | 1/4 (25.0%; 0.6–80.6) | 5/12 (41.7%; 15.2–72.3) | 6/15 (40.0%; 16.3–67.7) | |

| Total | 2/5 (40.0%; 5.3–85.3) | 6/14 (42.9%; 17.7–71.1) | 8/19 (42.1%; 20.3–66.5) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pino-Vera, R.; Abreu-Acosta, N.; Afonso, O.; Foronda, P. Potentially Zoonotic Bacteria in Exotic Freshwater Turtles from the Canary Islands (Spain). Biology 2025, 14, 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121753

Pino-Vera R, Abreu-Acosta N, Afonso O, Foronda P. Potentially Zoonotic Bacteria in Exotic Freshwater Turtles from the Canary Islands (Spain). Biology. 2025; 14(12):1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121753

Chicago/Turabian StylePino-Vera, Román, Néstor Abreu-Acosta, Oscar Afonso, and Pilar Foronda. 2025. "Potentially Zoonotic Bacteria in Exotic Freshwater Turtles from the Canary Islands (Spain)" Biology 14, no. 12: 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121753

APA StylePino-Vera, R., Abreu-Acosta, N., Afonso, O., & Foronda, P. (2025). Potentially Zoonotic Bacteria in Exotic Freshwater Turtles from the Canary Islands (Spain). Biology, 14(12), 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121753