Immune Checkpoint Restoration as a Therapeutic Strategy to Halt Diabetes-Driven Atherosclerosis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Immune Checkpoint Biology and Dual Roles Across Systems

2.1. PD-1 Pathway as the Primary Brake on T Cell Effector Function

2.2. CTLA-4 Pathway as the Master Regulator of Costimulatory Signaling

3. Diabetic Atherosclerosis: An Immune Checkpoint-Impaired State

3.1. Hyperglycemia-Mediated Disruption of Checkpoint Networks

3.2. Pro-Atherogenic T Cell Polarization in Checkpoint-Deficient Environments

3.3. Treg Dysfunction Driving Immune Imbalance

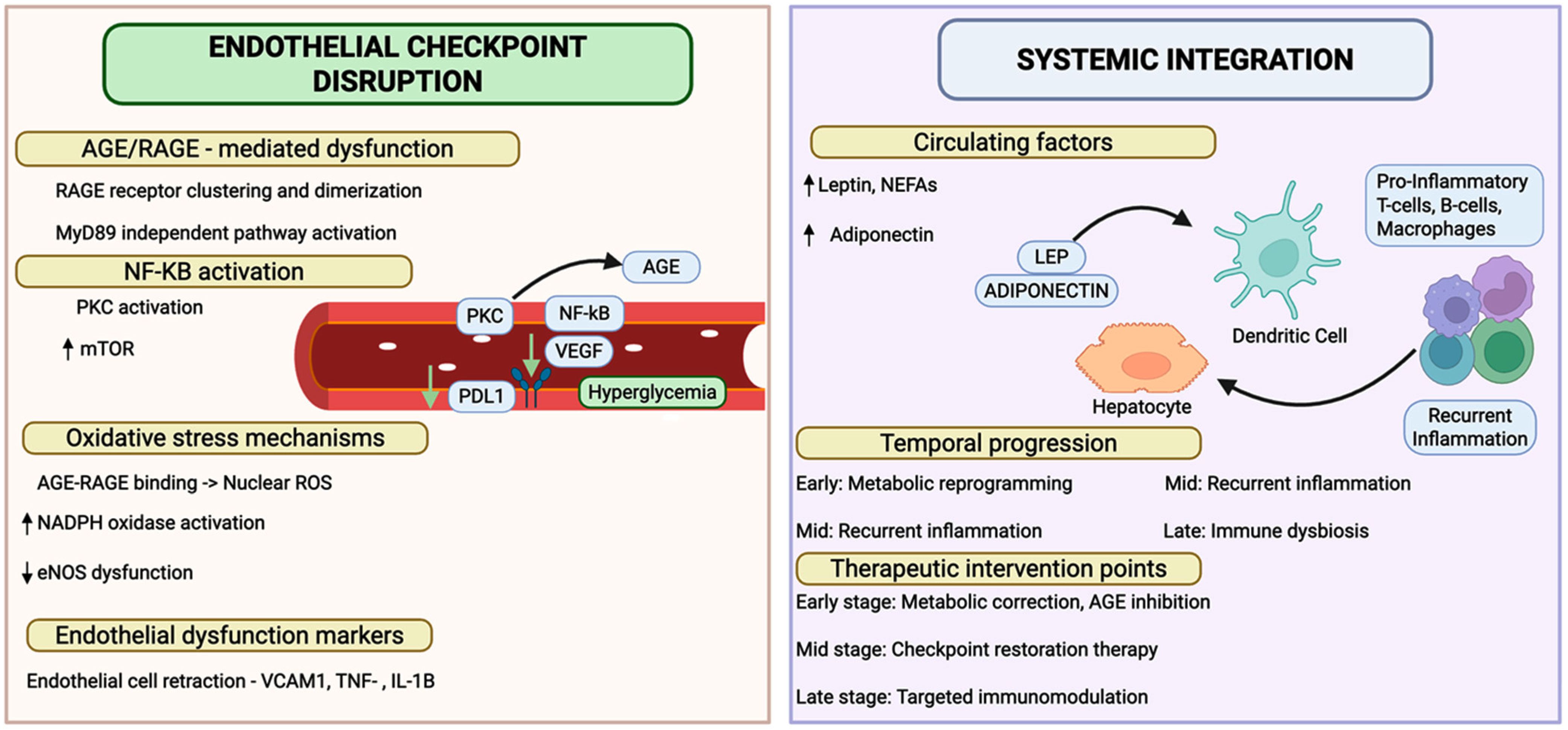

3.4. Endothelial Checkpoint Dysfunction Marks a Breach in the Vascular Immune Barrier

3.5. Checkpoint Dysfunction as a Driver of Plaque Vulnerability in Integrated Pathophysiology

4. Clinical Translation and Human Evidence for Checkpoint Dysfunction in Diabetic Atherosclerosis

5. Challenges in Translation and Therapy

5.1. Safety Considerations in Systemic Checkpoint Enhancement

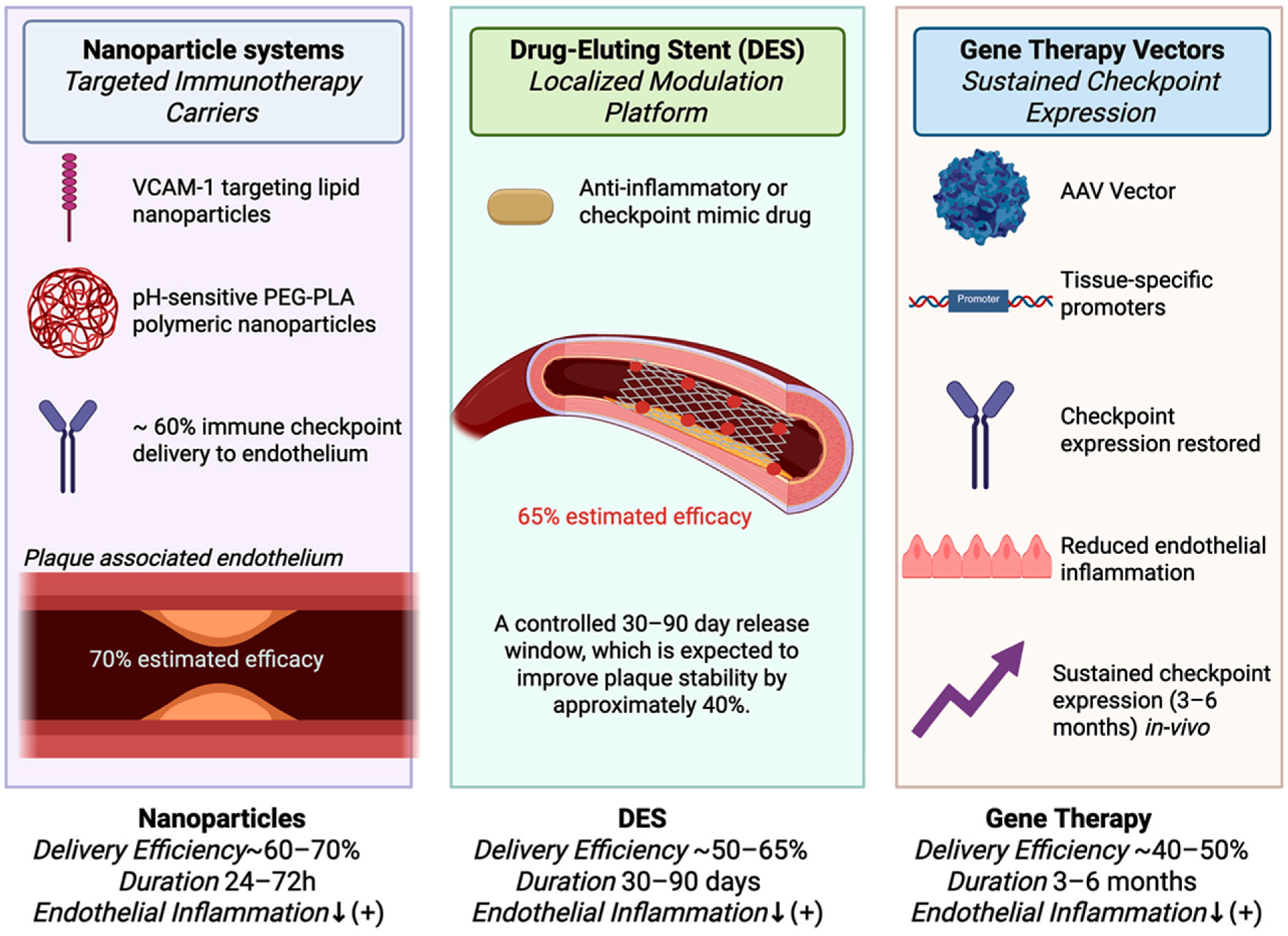

5.2. Vascular Targeting and Delivery Challenges

5.3. Bridging the Longitudinal Evidence Gap in Checkpoint Research

5.4. Clinical Management of Cancer Patients with Diabetes

5.5. Genetic Determinants and Personalized Medicine

5.6. Therapeutic Window and Dosing Considerations

5.7. Regulatory and Implementation Challenges

6. Future Directions in Translating Checkpoint Biology to Clinical Practice

6.1. Immune Checkpoint-Based Risk Stratification

6.2. Advanced Imaging and Molecular Visualization

6.3. Pharmacologic Interactions and Modulation of Checkpoints by Antidiabetic Therapies

6.4. Longitudinal Immune Surveillance and Dynamic Risk Assessment

6.5. Multi-Omics Integration and Predictive Modeling

6.6. Targeted Therapeutic Delivery Platforms

6.7. Precision Patient Selection and Therapeutic Optimization

6.8. Regulatory Framework and Safety Infrastructure

6.9. Interdisciplinary Integration and Implementation

6.10. Translational Barriers and Strategic Pathways for Clinical Implementation of Checkpoint-Based Therapies in Diabetic Atherosclerosis

6.11. Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells and Circadian Regulation the Unexplored Frontiers in Diabetic Atherosclerosis

6.12. Checkpoint Dysfunction in Type 1 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Risk

6.13. Translational Priorities and Research Roadmap for Checkpoint Restoration in Diabetes

6.14. Predictive Analytics and AI for Personalizing Checkpoint-Based Cardiovascular Therapies

6.15. Therapeutic Interactions and Molecular Crosstalk

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end products |

| AICAR | 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide |

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| BMAL1 | Brain and muscle ARNT-like protein-1 |

| CAR-T | Chimeric antigen receptor T cell |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| CD28 | Costimulatory receptor CD28 |

| CD80/CD86 | Costimulatory ligands B7-1/B7-2 |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DPP-4 | Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 |

| EC | Endothelial cell |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FAO | Fatty acid oxidation |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead box protein O1 |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GLUT | Glucose transporter |

| HbA1c | Glycated hemoglobin |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HEV | High endothelial venule |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| hsCRP | High-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| ICANS | Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IRF-1 | Interferon regulatory factor-1 |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| LAG-3 | Lymphocyte activation gene-3 |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| LDLR | Low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MACE | Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NAD+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NFAT | Nuclear factor of activated T cells |

| NK cells | Natural killer cells |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1/PD-L2 | Programmed death ligand-1/ligand-2 |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| RAGE | Receptor for advanced glycation end products |

| REV-ERB | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RT | Regulatory T cell (Treg) |

| RSK | Ribosomal S6 kinase |

| SGLT2 | Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 |

| SHP-1/SHP-2 | Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatases |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin-1 |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| TCR | T cell receptor |

| TET | Ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase |

| Th1/Th17 | T helper type 1/type 17 |

| TIM-3 | T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 |

| TIGIT | T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TRM | Tissue-resident memory T cell |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| VO2 | Oxygen consumption |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Hossain, M.J.; Al-Mamun, M.; Islam, M.R. Diabetes Mellitus, the Fastest Growing Global Public Health Concern: Early Detection Should Be Focused. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarson, T.R.; Acs, A.; Ludwig, C.; Panton, U.H. Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Literature Review of Scientific Evidence from across the World in 2007–2017. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Pan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Dong, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Hyperglycemia Induces an Immunosuppressive Microenvironment in Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases by Recruiting Peripheral Blood Monocytes through the CCL3-CCR1 Axis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtukiewicz, M.Z.; Rek, M.M.; Karpowicz, K.; Górska, M.; Polityńska, B.; Wojtukiewicz, A.M.; Moniuszko, M.; Radziwon, P.; Tucker, S.C.; Honn, K.V. Inhibitors of Immune Checkpoints-PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4-New Opportunities for Cancer Patients and a New Challenge for Internists and General Practitioners. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021, 40, 949–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Xi, Q.; Shen, H.; Zhang, R. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Breakthroughs in Cancer Treatment. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Paraskar, G.; Jha, M.; Gupta, G.L.; Prajapati, B.G. Deciphering Regulatory T-Cell Dynamics in Cancer Immunotherapy: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Innovations. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2024, 7, 2215–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Wang, S.H.; Tian, J.; Zhou, S. The Impact of Immune Checkpoint Inhibition on Atherosclerosis in Cancer Patients. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1604989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, E.I.; Desai, A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Pathways Similarities, Differences, and Implications of Their Inhibition. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 39, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Tsang, V.; Clifton-Bligh, R.; Carlino, M.S.; Tse, T.; Huang, Y.; Oatley, M.; Cheung, N.W.; Long, G.V.; Menzies, A.M.; et al. Hyperglycemia in Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Key Clinical Challenges and Multidisciplinary Consensus Recommendations. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobni, Z.D.; Alvi, R.M.; Taron, J.; Zafar, A.; Murphy, S.P.; Rambarat, P.K.; Mosarla, R.C.; Lee, C.; Zlotoff, D.A.; Raghu, V.K.; et al. Association between Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors with Cardiovascular Events and Atherosclerotic Plaque. Circulation 2020, 142, 2299–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q. Immune Cell Contribution to Vascular Complications in Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1549945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Gao, M.; Wang, W.; Chen, K.; Huang, L.; Liu, Y. Diabetic Vascular Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grievink, H.W.; Smit, V.; Verwilligen, R.A.F.; Bernabé Kleijn, M.N.A.; Smeets, D.; Binder, C.J.; Yagita, H.; Moerland, M.; Kuiper, J.; Bot, I.; et al. Stimulation of the PD-1 Pathway Decreases Atherosclerotic Lesion Development in Ldlr Deficient Mice. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 740531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, L.; Vina, E.; Ljubetic, J.; Meneur, C.; Tarroux, D.; Baez, M.; Marino, A.; Ortega, N.; Knorr, D.A.; Ravetch, J.V.; et al. Fc-Optimized Anti-CTLA-4 Antibodies Increase Tumor-Associated High Endothelial Venules and Sensitize Refractory Tumors to PD-1 Blockade. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Tai, P.W.L.; Gao, G. Adeno-Associated Virus Vector as a Platform for Gene Therapy Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 358–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ville, S.; Poirier, N.; Blancho, G.; Vanhove, B. Costimulatory Blockade of the CD28/CD80-86/CTLA-4 Balance in Transplantation: Impact on Memory T Cells? Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.; Jeffery, L.E.; Sansom, D.M. Understanding the CD28/CTLA-4 (CD152) Pathway and Its Implications for Costimulatory Blockade. Am. J. Transplant. 2014, 14, 1985–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, N.; Tardiel-Cyril, D.R.; Davtyan, A.; Generali, D.; Roudi, R.; Li, Y. CTLA-4 in Regulatory T Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Gao, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Shan, X.; Sun, Y.; Ma, D. Role of Treg Cell Subsets in Cardiovascular Disease Pathogenesis and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1331609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.; Torelli, S.; Cheng, E.; Batchelder, R.; Waliany, S.; Neal, J.; Witteles, R.; Nguyen, P.; Cheng, P.; Zhu, H. Immunotherapy-Associated Atherosclerosis: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Findings and Implications for Future Research. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 25, 715–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcia Durán, J.G.; Das, D.; Gildea, M.; Amadori, L.; Gourvest, M.; Kaur, R.; Eberhardt, N.; Smyrnis, P.; Cilhoroz, B.; Sajja, S.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Landscape of Human Atherosclerosis and Influence of Cardiometabolic Factors. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 3, 1482–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Li, H.F.; Li, S. PD-1-Mediated Inhibition of T Cell Activation: Mechanisms and Strategies for Cancer Combination Immunotherapy. Cell Insight 2024, 3, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, H.; Kuroda, H.; Matsunaga, T.; Osaki, T.; Ikeguchi, M. Increased PD-1 Expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells Is Involved in Immune Evasion in Gastric Cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 107, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Wolchok, J.D.; Chen, L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 Pathway Blockade for Cancer Therapy: Mechanisms, Response Biomarkers, and Combinations. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 328rv4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veluswamy, P.; Wacker, M.; Scherner, M.; Wippermann, J. Delicate Role of Pd-L1/Pd-1 Axis in Blood Vessel Inflammatory Diseases: Current Insight and Future Significance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdagul, A.; Sulzmaier, F.J.; Chen, X.L.; Pattillo, C.B.; Schlaepfer, D.D.; Orr, A.W. Oxidized LDL Induces FAK-Dependent RSK Signaling to Drive NF-ΚB Activation and VCAM-1 Expression. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.M.; Ma, Y.; Yin, Z.; Xia, Y.; Du, J.; Huang, J.Y.; Huang, J.J.; Zou, L.; Ye, Z.; Huang, Z. Current Understanding of CTLA-4: From Mechanism to Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1198365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner-Weinzierl, M.C.; Rudd, C.E. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Control of T-Cell Motility and Migration: Implications for Tumor Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsoukis, N.; Weaver, J.D.; Strauss, L.; Herbel, C.; Seth, P.; Boussiotis, V.A. Immunometabolic Regulations Mediated by Coinhibitory Receptors and Their Impact on T Cell Immune Responses. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.S.K. Treg and CTLA-4: Two Intertwining Pathways to Immune Tolerance. J. Autoimmun. 2013, 45, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.; Oberle, N.; Krammer, P.H. Molecular Mechanisms Oftreg-Mediatedt Cell Suppression. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, M.; Charmsaz, S.; Hallab, E.; Fang, M.; Kao, C.; Brancati, M.; Munjal, K.; Li, H.L.; Leatherman, J.M.; Griffin, E.; et al. Anti-CTLA4 Therapy Leads to Early Expansion of a Peripheral Th17 Population and Induction of Th1 Cytokines. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2025, 13, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poels, K.; van Leent, M.M.T.; Reiche, M.E.; Kusters, P.J.H.; Huveneers, S.; de Winther, M.P.J.; Mulder, W.J.M.; Lutgens, E.; Seijkens, T.T.P. Antibody-Mediated Inhibition of CTLA4 Aggravates Atherosclerotic Plaque Inflammation and Progression in Hyperlipidemic Mice. Cells 2020, 9, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quandt, Z.; Perdigoto, A.; Anderson, M.S.; Herold, K.C. Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Autoimmune Diabetes: An Autoinflammatory Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2025, 15, a041603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patsoukis, N.; Bardhan, K.; Chatterjee, P.; Sari, D.; Liu, B.; Bell, L.N.; Karoly, E.D.; Freeman, G.J.; Petkova, V.; Seth, P.; et al. PD-1 Alters T-Cell Metabolic Reprogramming by Inhibiting Glycolysis and Promoting Lipolysis and Fatty Acid Oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zong, M.; Fan, L. Metabolic Regulation of Th17 and Treg Cell Balance by the MTOR Signaling. Metabol. Open 2025, 26, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Yin, Z. Advanced Glycation End Products Regulate the Receptor of AGEs Epigenetically. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1062229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xiao, H.; Xiang, Y.; Zhong, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. Strategies to Overcome PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Resistance: Focusing on Combination with Immune Checkpoint Blockades. J. Cancer 2025, 16, 3425–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zou, M.H. Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Targets for Diabetic Endothelial Dysfunction. Circulation 2009, 120, 1266–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Deng, F.; Deng, Z. Oxidative Stress: Signaling Pathways, Biological Functions, and Disease. MedComm 2025, 6, 70268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warda, M.; Tekin, S.; Gamal, M.; Khafaga, N.; Çelebi, F.; Tarantino, G. Lipid Rafts: Novel Therapeutic Targets for Metabolic, Neurodegenerative, Oncological, and Cardiovascular Diseases. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Haskins, K.; Bradley, B.; Gilman, J.; Gamboni-Robertson, F.; Flores, S.C. Autoimmune-Mediated Vascular Injury Occurs Prior to Sustained Hyperglycemia in a Murine Model of Type I Diabetes Mellitus. J. Surg. Res. 2011, 168, e195–e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, K.D.; Tong, Z.W.M.; Rowntree, L.C.; van de Sandt, C.E.; Ronacher, K.; Grant, E.J.; Dorey, E.S.; Gallo, L.A.; Gras, S.; Kedzierska, K.; et al. Increasing HbA1c Is Associated with Reduced CD8+ T Cell Functionality in Response to Influenza Virus in a TCR-Dependent Manner in Individuals with Diabetes Mellitus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boye, K.S.; Thieu, V.T.; Lage, M.J.; Miller, H.; Paczkowski, R. The Association Between Sustained HbA1c Control and Long-Term Complications Among Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Study. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 2208–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiese, K. FoxO Transcription Factors and Regenerative Pathways in Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Neurovascular Res. 2015, 12, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestreich, K.J.; Yoon, H.; Ahmed, R.; Boss, J.M. NFATc1 Regulates Programmed Death-1 Expression Upon T Cell Activation. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 4832–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.; Nguyen, H.; Chambers, C.; Kang, J. Dual Function of CTLA-4 in Regulatory T Cells and Conventional T Cells to Prevent Multiorgan Autoimmunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 1524–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Wang, X.; Pei, Z.; Hu, X. Glycemic Control, HbA1c Variability, and Major Cardiovascular Adverse Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes Patients with Elevated Cardiovascular Risk: Insights from the ACCORD Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yin, D.; Dou, K. Intensified Glycemic Control by HbA1c for Patients with Coronary Heart Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: A Review of Findings and Conclusions. Cardiovasc. Diabetol 2023, 22, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, M.L.; Boudou, P.; Squara, P.A.; Delyon, J.; Allayous, C.; Mourah, S.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Lebbé, C.; Baroudjian, B.; Gautier, J.F. Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment Induces an Increase in HbA1c in Nondiabetic Patients. Melanoma Res. 2019, 29, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, W.; Gao, Q.; Tan, K.C.B.; Lee, C.H.; Ling, G.S. Metabolic Hallmarks of Type 2 Diabetes Compromise T Cell Function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Jagannath, C. Crosstalk between Metabolism and Epigenetics during Macrophage Polarization. Epigenetics Chromatin 2025, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalous, K.S.; Wynia-Smith, S.L.; Olp, M.D.; Smith, B.C. Mechanism of Sirt1 NAD+-Dependent Protein Deacetylase Inhibition by Cysteine S-Nitrosation. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 25398–25410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.J.; Xi, M.J.; Xia, B.H.; Deng, K.; Yang, J.L. Lipid Metabolic Reprogramming in Tumor Microenvironment: From Mechanisms to Therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol 2023, 16, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, P.; Saha, D.; Giri, A.; Bhatnagar, A.R.; Chakraborty, A. Decoding the CD36-Centric Axis in Gastric Cancer: Insights into Lipid Metabolism, Obesity, and Hypercholesterolemia. Int. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Yang, Q.; Wang, H.; Melick, C.H.; Navlani, R.; Frank, A.R.; Jewell, J.L. Glutamine and Asparagine Activate MTORC1 Independently of Rag GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 2890–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Natarajan, R. Epigenetic Modifications in Metabolic Memory: What Are the Memories, and Can We Erase Them? Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2022, 323, C570–C582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Xiang, X.; Nie, L.; Guo, X.; Zhang, F.; Wen, C.; Xia, Y.; Mao, L. The Emerging Role of Th1 Cells in Atherosclerosis and Its Implications for Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1079668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, P.A.; Goswami, A.; Mazzuca, D.M.; Kim, K.; O’Gorman, D.B.; Hess, D.A.; Welch, I.D.; Young, H.A.; Singh, B.; McCormick, J.K.; et al. Rapid and Rigorous IL-17A Production by a Distinct Subpopulation of Effector Memory T Lymphocytes Constitutes a Novel Mechanism of Toxic Shock Syndrome Immunopathology. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 2805–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, J.S.; Bhatti, G.K.; Reddy, P.H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Disorders—A Step towards Mitochondria Based Therapeutic Strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, C.; Bao, J.; Chen, Y. CD4+ T Cell Exhaustion Revealed by High PD-1 and LAG-3 Expression and the Loss of Helper T Cell Function in Chronic Hepatitis B. BMC Immunol. 2019, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminskiy, Y.; Melenhorst, J.J. STAT3 Role in T-Cell Memory Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagov, A.V.; Markin, A.M.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Sukhorukov, V.N.; Orekhov, A.N. The Role of Macrophages in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Cells 2023, 12, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, M.J.; Gjurich, B.N.; Phillips, T.; Galkina, E.V. The IL-17A/IL-17RA Axis Plays a Proatherogenic Role via the Regulation of Aortic Myeloid Cell Recruitment. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, J.C.; Cruz, R.P.; Kerjner, A.; Geisbrecht, J.; Sawchuk, T.; Fraser, S.A.; Hudig, D.; Bleackley, R.C.; Jirik, F.R.; McManus, B.M.; et al. Granzyme B Induces Endothelial Cell Apoptosis and Contributes to the Development of Transplant Vascular Disease. Am. J. Transplant. 2005, 5, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Ming, Y.; Wu, J.; Cui, G. Cellular Metabolism Regulates the Differentiation and Function of T-Cell Subsets. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaddi, P.K.; Osborne, D.G.; Nicklawsky, A.; Williams, N.K.; Menon, D.R.; Smith, D.; Mayer, J.; Reid, A.; Domenico, J.; Nguyen, G.H.; et al. CTLA4 MRNA Is Downregulated by MiR-155 in Regulatory T Cells, and Reduced Blood CTLA4 Levels Are Associated with Poor Prognosis in Metastatic Melanoma Patients. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1173035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, O.S.; Zheng, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Attridge, K.; Manzotti, C.; Schmidt, E.M.; Baker, J.; Jeffery, L.E.; Kaur, S.; Briggs, Z.; et al. Trans-Endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: A Molecular Basis for the Cell-Extrinsic Function of CTLA-4. Science 2011, 332, 600–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam, N.; Reddy, M.A.; Guha, M.; Natarajan, R. High Glucose-Induced Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokine and Chemokine Genes in Monocytic Cells. Diabetes 2003, 52, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbrone, M.A.; García-Cardeña, G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.K.; Jung, C.H. Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors-Induced Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: From Its Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Practice. Diabetes Metab. J. 2023, 47, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.L.; Liang, C.; Jiang, W.W.; Zhang, M.; Guan, H.; Hong, Z.; Zhu, D.; Shang, A.Q.; Yu, C.J.; Zhang, Z.R. Inhibition of CTLA-4 Accelerates Atherosclerosis in Hyperlipidemic Mice by Modulating the Th1/Th2 Balance via the NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.K.; Chin, K.Y.; Suhaimi, F.H.; Fairus, A.; Ima-Nirwana, S. Animal Models of Metabolic Syndrome: A Review. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.H.; Chiang, C.H.; Ma, K.S.K.; Hsia, Y.P.; Lee, Y.W.; Wu, H.R.; Chiang, C.H.; Peng, C.Y.; Wei, J.C.C.; Shiah, H.S.; et al. The Incidence and Risk of Cardiovascular Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Asian Populations. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 52, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, G.; Chen, Y.-H.; Nie, T.; Yang, M.; Luo, K.; Zheng, C.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer: The Increased Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Events and Progression of Coronary Artery Calcium. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poels, K.; van Leent, M.M.T.; Boutros, C.; Tissot, H.; Roy, S.; Meerwaldt, A.E.; Toner, Y.C.A.; Reiche, M.E.; Kusters, P.J.H.; Malinova, T.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy Aggravates T Cell–Driven Plaque Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. JACC CardioOncol. 2020, 2, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louie, J.Z.; Shiffman, D.; Rowland, C.M.; Kenyon, N.S.; Bernal-Mizrachi, E.; McPhaul, M.J.; Garg, R. Predictors of Lack of Glycemic Control in Persons with Type 2 Diabetes. Clin. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcone, M.; Fousteri, G. Role of the PD-1/PD-L1 Dyad in the Maintenance of Pancreatic Immune Tolerance for Prevention of Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Yin, X.; Chen, L. Regulatory T Cells: Masterminds of Immune Equilibrium and Future Therapeutic Innovations. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1457189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, J.; Sha, W.; Lei, T. Comprehensive Treatment of Diabetic Endothelial Dysfunction Based on Pathophysiological Mechanism. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1509884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Cardiovascular Adverse Effects of Immunotherapy in Cancer: Insights and Implications. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1601808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, Y.; Tang, F.; Wei, Y.-Q.; Wei, X.-W. Immunosuppressive Cells in Cancer: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Targets. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, G.; Yu, H. Enhancing Antitumor Immunity: The Role of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors, Anti-Angiogenic Therapy, and Macrophage Reprogramming. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1526407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, P.; Lutgens, E.; Seijkens, T.T.P. Exploring Immune Checkpoints as Potential Therapeutic Targets in Atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Liu, J.; Hu, W.; Chen, Z.; Lan, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhong, Z.; Zhang, D.; et al. Targeting Pro-Inflammatory T Cells as a Novel Therapeutic Approach to Potentially Resolve Atherosclerosis in Humans. Cell Res. 2024, 34, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, V.; Kumari, P.; Singh, R.; Chopra, H.; Emran, T. Bin Novel Insights on the Role of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1: Potential Biomarkers for Cardiovascular Diseases. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 84, 104802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassiri, N. Precision Therapy Demands Precision Delivery in the Evolution of Treatment for Low-Flow Vascular Malformations. J. Vasc. Surg. 2025, 13, 102262. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Fan, L.; Ma, Y.; Tian, K.; Qiu, W.; Wei, A.; Fu, W.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Vascular Endothelial Cell-Targeted MRNA Delivery via Synthetic Lipid Nanoparticles for Venous Thrombosis Prevention. J. Control. Release 2025, 388, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabretta, R.; Beer, L.; Prosch, H.; Kifjak, D.; Zisser, L.; Binder, P.; Grünert, S.; Langsteger, W.; Li, X.; Hacker, M. Induction of Arterial Inflammation by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Lung Cancer Patients as Measured by 2-[18F]FDG Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography Depends on Pre-Existing Vascular Inflammation. Life 2024, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Fang, F.; Wang, B. Nanoparticle Technologies for Liver Targeting and Their Applications in Liver Diseases. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1661872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.S.; Wang, C.P.J.; Park, W.; Park, C.G. Short Review on Advances in Hydrogel-Based Drug Delivery Strategies for Cancer Immunotherapy. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2022, 19, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Kong, X.; Xia, L.; Wu, R.; Zhu, H.; Yang, Z. The Role of Total-Body PET in Drug Development and Evaluation: Status and Outlook. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 46S–53S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotti, F.; Kumar, N.; Prevete, N.; Marotta, M.; Sorriento, D.; Ieranò, C.; Ronchi, A.; Marino, F.Z.; Moretti, S.; Colella, R.; et al. PD-1 Blockade Delays Tumor Growth by Inhibiting an Intrinsic SHP2/Ras/MAPK Signalling in Thyroid Cancer Cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubel, J.M.; Barbati, Z.R.; Burger, C.; Wirtz, D.C.; Schildberg, F.A. The Role of PD-1 in Acute and Chronic Infection. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Yang, Y.; Deng, K.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Bai, L.; Wang, Y.; Lu, C. Type I Interferon Activates PD-1 Expression through Activation of the STAT1-IRF2 Pathway in Myeloid Cells. Cells 2024, 13, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, M.; Cho, E.; Gliozheni, E.; Salem, Y.; Cheung, J.; Ichii, H. Pathology of Diabetes-Induced Immune Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, S.; Naka, K.K.K.; Papadakis, M.; Bechlioulis, A.; Tsatsoulis, A.; Michalis, L.K.; Tigas, S. Effect of Glycemic Control on Markers of Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 1856–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessomo, F.Y.N.; Mandizadza, O.O.; Mukuka, C.; Wang, Z.Q. A Comprehensive Review on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Induced Cardiotoxicity Characteristics and Associated Factors. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardin, S.; Ruffilli, B.; Costantini, P.; Mollace, R.; Taglialatela, I.; Pagnesi, M.; Chiarito, M.; Soldato, D.; Cao, D.; Conte, B.; et al. Navigating Cardiotoxicity in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: From Diagnosis to Long-Term Management. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Xu, W. Are Programmed Cell Death 1 Gene Polymorphisms Correlated with Susceptibility to Rheumatoid Arthritis? Medicine 2017, 96, e7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipel, K.; Shaforostova, I.; Nilius, H.; Bacher, U.; Pabst, T. Clinical Impact of CTLA-4 Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism in DLBCL Patients Treated with CAR-T Cell Therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, D.; Azar, N.S.; Eid, A.A.; Azar, S.T. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Diabetes Mellitus: Potential Role of t Cells in the Underlying Mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Fernandes, M.; Lee, J.; Merino, J.; Kwak, S.H. Exploring the Shared Genetic Landscape of Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: Findings and Future Implications. Diabetologia 2025, 68, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaman, J.A. The Future of Pharmacogenomics: Integrating Epigenetics, Nutrigenomics, and Beyond. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakasis, P.; Theofilis, P.; Patoulias, D.; Vlachakis, P.K.; Antoniadis, A.P.; Fragakis, N. Diabetes-Driven Atherosclerosis: Updated Mechanistic Insights and Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.R.; Wu, X.L.; Sun, Y.L. Therapeutic Targets and Biomarkers of Tumor Immunotherapy: Response versus Non-Response. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.; Cui, Z.Y.; Huang, X.F.; Zhang, D.D.; Guo, R.J.; Han, M. Inflammation and Atherosclerosis: Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Intervention. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, L.; Zou, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Xing, B.; Feng, J.; Jin, Y.; Cheng, M. Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Atherosclerosis. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicak, M.; Bozkus, C.C.; Bhardwaj, N. Checkpoint Therapy in Cancer Treatment: Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, 184846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emens, L.A.; Romero, P.J.; Anderson, A.C.; Bruno, T.C.; Capitini, C.M.; Collyar, D.; Gulley, J.L.; Hwu, P.; Posey, A.D.; Silk, A.W.; et al. Challenges and Opportunities in Cancer Immunotherapy: A Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Strategic Vision. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e009063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohimi, W.N.L.H.W.; Tahir, N.A.M. The Cost-Effectiveness of Different Types of Educational Interventions in Type II Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 953341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasis, P.; Theofilis, P.; Vlachakis, P.K.; Grigoriou, K.; Patoulias, D.; Antoniadis, A.P.; Fragakis, N. Reprogramming Atherosclerosis: Precision Drug Delivery, Nanomedicine, and Immune-Targeted Therapies for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, E.; Van Genugten, E.A.J.; Heskamp, S.; De Vries, I.J.M.; Van Herpen, C.; Koenen, H.J.P.M.; Kneilling, M.; Van Der Post, R.S.; Van Dop, W.A.; Westdorp, H.; et al. Exploring Molecular Imaging to Investigate Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Toxicity. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.A.; Lanzar, Z.; Clark, J.T.; Hart, A.P.; Douglas, B.B.; Shallberg, L.; O’Dea, K.; Christian, D.A.; Hunter, C.A. PD-1 and CTLA-4 Exert Additive Control of Effector Regulatory T Cells at Homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 997376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y. Cardiovascular Risk Assessment and Screening in Diabetes. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. 2017, 6, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.M.; Tawakol, A.; Jaffer, F.A. Molecular Imaging of Atherosclerosis: A Clinical Focus. Curr. Cardiovasc. Imaging Rep. 2017, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, E.A.; Jaffer, F.A. Imaging Atherosclerosis and Risk of Plaque Rupture. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2013, 15, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Sheikholeslami, M.A.; Mozaffari, M.; Mortada, Y. Innovative Immunotherapies and Emerging Treatments in Type 1 Diabetes Management. Diabetes Epidemiol. Manag. 2025, 17, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelyanova, L.; Bai, X.; Yan, Y.; Bosnjak, Z.J.; Kress, D.; Warner, C.; Kroboth, S.; Rudic, T.; Kaushik, S.; Stoeckl, E.; et al. Biphasic Effect of Metformin on Human Cardiac Energetics. Transl. Res. 2021, 229, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Coutifaris, P.; Brocks, D.; Wang, G.; Azar, T.; Solis, S.; Nandi, A.; Anderson, S.; Han, N.; Manne, S.; et al. Combination Anti-PD-1 and Anti-CTLA-4 Therapy Generates Waves of Clonal Responses That Include Progenitor-Exhausted CD8+ T Cells. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1582–1597.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatiwada, N.; Hong, Z. Potential Benefits and Risks Associated with the Use of Statins. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.T.; Yun, M.Z. The Impact of Sulfonylureas on Diverse Ion Channels: An Alternative Explanation for the Antidiabetic Actions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1528369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, J.A.; Lin, S.M.; Liu, Y.C.; Hsu, J.Z.; Huang, A.H.; Munir, K.M.; Peng, C.C.H.; Loh, C.H.; Huang, H.K. Association of SGLT2 Inhibitors and GLP-1 Receptor Agonists with the Risk of Parkinson’s Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Propensity Score–Matched Cohort Study with Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 229, 112914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, H.; Bailey, L.C.; Bauer, L.G.; Voronkov, M.; Baxter, M.; Huber, K.V.M.; Khorasanizadeh, S.; Ray, D.; Rastinejad, F. Pharmacological Targeting of BMAL1 Modulates Circadian and Immune Pathways. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2025, 21, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, A.; Jaffee, E.M.; Zaidi, N. Cancers. Emerging Strategies for Combination Checkpoint Modulators in Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3209–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, E.; Patanwala, A.E.; Lu, C.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Stocker, S.L.; Alffenaar, J.W.C. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Biomarkers; towards Better Dosing of Antimicrobial Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, H.L.; Wang, H.C.; Kuburic, J.; Alzhrani, A.; Hester, J.; Issa, F. Immune Monitoring for Advanced Cell Therapy Trials in Transplantation: Which Assays and When? Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 664244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yang, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, J.; Guo, H.; Yang, R. Single-Cell Sequencing to Multi-Omics: Technologies and Applications. Biomark Res. 2024, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, D.M.; Giannarelli, C. Immune Cell Profiling in Atherosclerosis: Role in Research and Precision Medicine. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, J.R.; Wu, Y.; Zacchi, L.F.; Ta, H.T. Targeting Endothelial Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 in Atherosclerosis: Drug Discovery and Development of Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1-Directed Novel Therapeutics. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2278–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Dutta, P.; Saha, D.; Singh, M.; Prasad, C.P.; Pushpam, D.; Shankar, A.; Saini, D. Chimeric Antigen Receptor CAR-T Therapy on the Move: Current Applications and Future Possibilities. Curr. Tissue Microenviron. Rep. 2023, 4, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, G.; Valencia, L.M.; Martin-Ozimek, A.; Soto, Y.; Proctor, S.D. Atherosclerosis: From Lipid-Lowering and Anti-Inflammatory Therapies to Targeting Arterial Retention of ApoB-Containing Lipoproteins. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1485801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M.; Poznańska, J.; Fechner, F.; Michalska, N.; Paszkowska, S.; Napierała, A.; Mackiewicz, A. Cancer Vaccine Therapeutics: Limitations and Effectiveness—A Literature Review. Cells 2023, 12, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, J.; Drescher, E.; Simón-Campos, J.A.; Emery, P.; Greenwald, M.; Kivitz, A.; Rha, H.; Yachi, P.; Kiley, C.; Nirula, A. A Phase 2 Trial of Peresolimab for Adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis. N Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naing, A.; McKean, M.; Rosen, L.S.; Sommerhalder, D.; Shaik, N.M.; Wang, I.M.; Le Corre, C.; Kern, K.A.; Mishra, N.H.; Pal, S.K. First-in-Human Phase I Study to Evaluate Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, Immunogenicity, and Antitumor Activity of PF-07209960 in Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, W.; Won, T.; Daoud, A.; Čiháková, D. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Associated Cardiovascular Immune-Related Adverse Events. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1340373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravera, F.; Dameri, M.; Lombardo, I.; Stabile, M.; Becherini, P.; Fallani, N.; Scarsi, C.; Cigolini, B.; Gentilcore, G.; Domnich, A.; et al. Biological Modifications of the Immune Response to COVID-19 Vaccine in Patients Treated with Rituximab and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.A.; Sparapani, R.; Osinski, K.; Zhang, J.; Blessing, J.; Cheng, F.; Hamid, A.; Berman, G.; Lee, K.; BagheriMohamadiPour, M.; et al. Establishing an Interdisciplinary Research Team for Cardio-Oncology Artificial Intelligence Informatics Precision and Health Equity. Am. Heart J. Plus 2022, 13, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, D.-B.; Wang, C.-H.; Sang, M.; Sun, X.-D.; Chen, G.-P.; Ji, K.-K. Stem Cell Therapy for Diabetes: Advances, Prospects, and Challenges. World J. Diabetes 2025, 16, 107344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, L.; Ferdinandy, P.; Rassaf, T. Cellular Alterations in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy-Related Cardiac Dysfunction. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2024, 21, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelec, M.; Detka, J.; Mieszczak, P.; Sobocińska, M.K.; Majka, M. Immunomodulation—A General Review of the Current State-of-the-Art and New Therapeutic Strategies for Targeting the Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1127704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Cho, M.; Kim, E.; Seo, Y.; Cha, J.H. PD-L1: From Cancer Immunotherapy to Therapeutic Implications in Multiple Disorders. Mol. Ther. 2024, 32, 4235–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichloo, A.; Albosta, M.; Dahiya, D.; Guidi, J.C.; Aljadah, M.; Singh, J.; Shaka, H.; Wani, F.; Kumar, A.; Lekkala, M. Systemic Adverse Effects and Toxicities Associated with Immunotherapy: A Review. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 12, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disanto, R.M.; Subramanian, V.; Gu, Z. Recent Advances in Nanotechnology for Diabetes Treatment. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 7, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Xie, Q.; Sun, Y. Advances in Nanomaterial-Based Targeted Drug Delivery Systems. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1177151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canossi, A.; Vistoli, F.; Sebastiani, P.; Colanardi, A.; Del Beato, T.; Panarese, A. Serum PD-L1 and CTLA-4 Levels as Biomarkers of Acute Rejection and Renal Dysfunction in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transpl. Immunol. 2025, 92, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namitokov, A.; Karabakhtsieva, K.; Malyarevskaya, O. Inflammatory and Lipid Biomarkers in Early Atherosclerosis: A Comprehensive Analysis. Life 2024, 14, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicha, I.; Chauvierre, C.; Texier, I.; Cabella, C.; Metselaar, J.M.; Szebeni, J.; Dézsi, L.; Alexiou, C.; Rouzet, F.; Storm, G.; et al. From Design to the Clinic: Practical Guidelines for Translating Cardiovascular Nanomedicine. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 1714–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Wei, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhou, N.; Xu, X.; Deng, X.; Liu, T.; Zou, Y. The Immune System in Cardiovascular Diseases: From Basic Mechanisms to Therapeutic Implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghbash, P.S.; Eslami, N.; Shamekh, A.; Entezari-Maleki, T.; Baghi, H.B. SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The Role of PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 Axis. Life Sci. 2021, 270, 119124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimmino, G.; D’Elia, S.; Morello, M.; Titolo, G.; Luisi, E.; Solimene, A.; Serpico, C.; Conte, S.; Natale, F.; Loffredo, F.S.; et al. Cardio-Pulmonary Features of Long COVID: From Molecular and Histopathological Characteristics to Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Barrera Adame, O.; Nickas, M.; Robison, J.; Khatchadourian, C.; Venketaraman, V. Type 2 Diabetes Contributes to Altered Adaptive Immune Responses and Vascular Inflammation in Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 833355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobo, O.; Misra, S.; Banerjee, A.; Rutter, M.K.; Khunti, K.; Mamas, M.A. Post-COVID Changes and Disparities in Cardiovascular Mortality Rates in the United States. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 46, 102876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Dutta, P.; Rebello, K.R.; Shankar, A.; Chakraborty, A. Exploring the Potential Link between Human Papillomavirus Infection and Coronary Artery Disease: A Review of Shared Pathways and Mechanisms. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2025, 480, 3971–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Zhan, H.; Zhan, J.; Li, X.; Lin, X.; Sun, W. Breaking Hypoxic Barrier: Oxygen-Supplied Nanomaterials for Enhanced T Cell-Mediated Tumor Immunotherapy. Int. J. Pharm. X 2025, 10, 100400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M. Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells: Decoding Intra-Organ Diversity with a Gut Perspective. Inflamm. Regen. 2024, 44, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Li, L.; Wang, M.; Ma, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, B.; Liu, H.; et al. Diabetes Mellitus Promotes the Development of Atherosclerosis: The Role of NLRP3. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 900254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jong, M.J.M.; Depuydt, M.A.C.; Schaftenaar, F.H.; Liu, K.; Maters, D.; Wezel, A.; Smeets, H.J.; Kuiper, J.; Bot, I.; Van Gisbergen, K.; et al. Resident Memory T Cells in the Atherosclerotic Lesion Associate with Reduced Macrophage Content and Increased Lesion Stability. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1318–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.C.; Joller, N.; Kuchroo, V.K. Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: Co-Inhibitory Receptors with Specialized Functions in Immune Regulation. Immunity 2016, 44, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbudi, A.; Khairani, S.; Tjahjadi, A.I. Interplay Between Insulin Resistance and Immune Dysregulation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Implications for Therapeutic Interventions. Immunotargets Ther. 2025, 14, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schøller, A.S.; Nazerai, L.; Christensen, J.P.; Thomsen, A.R. Functionally Competent, PD-1+ CD8+ Trm Cells Populate the Brain Following Local Antigen Encounter. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 595707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkel, J.M.; Masopust, D. Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells. Immunity 2014, 41, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slenders, L.; Tessels, D.E.; van der Laan, S.W.; Pasterkamp, G.; Mokry, M. The Applications of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Atherosclerotic Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 826103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Dutta, P.; Hussain, T.; Chakraborty, A. Dual Targeting of MiR-33 and MiR-92a in Atherosclerosis: Mechanistic Insights, Therapeutic Potential, and Translational Challenges. ExRNA 2025, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, B.M.; Pfeiffer, S.M.; Insua-Rodríguez, J.; Alshetaiwi, H.; Moshensky, A.; Song, W.A.; Mahieu, A.L.; Chun, S.K.; Lewis, A.N.; Hsu, A.; et al. Circadian Control of Tumor Immunosuppression Affects Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 1257–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Li, L. Circadian Clock Regulates Inflammation and the Development of Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 696554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, T.; Wang, K.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yan, Q.; Jiang, W.; Chen, C.; Zhao, K.; Feng, J.; Wang, W. Clock Genes in Pancreatic Disease Progression: From Circadian Regulation to Dysfunction. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2528449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahata, Y.; Kaluzova, M.; Grimaldi, B.; Sahar, S.; Hirayama, J.; Chen, D.; Guarente, L.P.; Sassone-Corsi, P. The NAD+-Dependent Deacetylase SIRT1 Modulates CLOCK-Mediated Chromatin Remodeling and Circadian Control. Cell 2008, 134, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Tanani, M.; Rabbani, S.A.; Ali, A.A.; Alfaouri, I.G.A.; Al Nsairat, H.; Al-Ani, I.H.; Aljabali, A.A.; Rizzo, M.; Patoulias, D.; Khan, M.A.; et al. Circadian Rhythms and Cancer: Implications for Timing in Therapy. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, K.H.C.; Haskologlu, I.C.; Erdag, E. Molecular Links Between Circadian Rhythm Disruption, Melatonin, and Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Updated Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, S.; Fujisue, K.; Yamanaga, K.; Sueta, D.; Usuku, H.; Tabata, N.; Ishii, M.; Hanatani, S.; Hoshiyama, T.; Kanazawa, H.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Soluble PD-L1 on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2024, 31, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabins, N.C.; Harman, B.C.; Barone, L.R.; Shen, S.; Santulli-Marotto, S. Differential Expression of Immune Checkpoint Modulators on in Vitro Primed CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibellini, L.; De Biasi, S.; Porta, C.; Lo Tartaro, D.; Depenni, R.; Pellacani, G.; Sabbatini, R.; Cossarizza, A. Single-Cell Approaches to Profile the Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wu, M.; Chen, F.; Chen, L. Circadian Rhythm Regulates the Function of Immune Cells and Participates in the Development of Tumors. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmers, S.; Rudensky, A.Y. The Cell-Intrinsic Circadian Clock Is Dispensable for Lymphocyte Differentiation and Function. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 1339–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.V.; Ma, W.; Miron, M.; Granot, T.; Guyer, R.S.; Carpenter, D.J.; Senda, T.; Sun, X.; Ho, S.H.; Lerner, H.; et al. Human Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells Are Defined by Core Transcriptional and Functional Signatures in Lymphoid and Mucosal Sites. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 2921–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derlin, T.; Tóth, Z.; Papp, L.; Wisotzki, C.; Apostolova, I.; Habermann, C.R.; Mester, J.; Klutmann, S. Correlation of Inflammation Assessed By18F-FDG PET, Active Mineral Deposition Assessed By18F-Fluoride PET, and Vascular Calcification in Atherosclerotic Plaque: A Dual-Tracer PET/CT Study. J. Nucl. Med. 2011, 52, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colli, M.L.; Hill, J.L.E.; Marroquí, L.; Chaffey, J.; Dos Santos, R.S.; Leete, P.; Coomans de Brachène, A.; Paula, F.M.M.; Op de Beeck, A.; Castela, A.; et al. PDL1 Is Expressed in the Islets of People with Type 1 Diabetes and Is Up-Regulated by Interferons-α and-γ via IRF1 Induction. EBioMedicine 2018, 36, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, K.C.; Delong, T.; Perdigoto, A.L.; Biru, N.; Brusko, T.M.; Walker, L.S.K. The Immunology of Type 1 Diabetes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jä Rvisalo, M.J.; Putto-Laurila, A.; Jartti, L.; Lehtimä, T.; Solakivi, T.; Rö, T.; Raitakari, O.T. Carotid Artery Intima-Media Thickness in Children with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2002, 51, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, A.E.; Sinclair, D.A. Sirtuins and NAD+ in the Development and Treatment of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 868–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, T.; De Block, C.; Schwartzbard, A.Z.; Newman, J.D. Diabetic Agents, From Metformin to SGLT2 Inhibitors and GLP1 Receptor Agonists: JACC Focus Seminar. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 1956–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Li, N.; Lin, W.; Shi, L.; Deng, M.; Tong, Q.; Yang, W. Machine Learning for Predicting Hyperglycemic Cases Induced by PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 6278854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkempetzaki, A.I.; Schatton, T.; Barthel, S.R. Galectin-9—An Emerging Glyco-Immune Checkpoint Target for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, D.R.; Luciano, F.C.; Anaya, B.J.; Ongoren, B.; Kara, A.; Molina, G.; Ramirez, B.I.; Sánchez-Guirales, S.A.; Simon, J.A.; Tomietto, G.; et al. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Applications in Drug Discovery and Drug Delivery: Revolutionizing Personalized Medicine. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Pan, D.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yan, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Yang, M.; Liu, G.P. Applications of Multi-Omics Analysis in Human Diseases. MedComm 2023, 4, e315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.J.; Wang, J.J.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Chen, T.Y.; Lipkova, J.; Lu, M.Y.; Sahai, S.; Mahmood, F. Algorithmic Fairness in Artificial Intelligence for Medicine and Healthcare. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 719–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horckmans, M.; Villamil, E.D.; Bianchini, M.; De Roeck, L.; Communi, D. Central Role of PD-L1 in Cardioprotection Resulting from P2Y4 Nucleotide Receptor Loss. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1006934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluijmert, N.J.; Atsma, D.E.; Quax, P.H.A. Post-Ischemic Myocardial Inflammatory Response: A Complex and Dynamic Process Susceptible to Immunomodulatory Therapies. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 647785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, X.; Chen, J.; Fu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Tao, H.; Li, Z. Microglia in Ischemic Stroke: Pathogenesis Insights and Therapeutic Challenges. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 3335–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Category | Key Findings | Clinical Insight | Translational Gap | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Checkpoint Blockade (ICI) and Cardiovascular (CV) Risk | ICIs increase CV events 3.4-fold | Validates that immune checkpoints serve protective roles in vasculature | Cancer populations differ from diabetics, unclear if same risk mechanisms apply directly in metabolic disease | [75] |

| T Cell Phenotyping in Diabetes | Diabetics show suppressed PD-1/CTLA-4 expression on T cells | Direct link between immune checkpoint impairment and atherosclerotic risk in diabetic patients | No longitudinal data to confirm if this dysfunction precedes or predicts CV events | [76] |

| Effect of Glycemic Control | Poor glucose control (HbA1c > 8.5%) associates with lower PD-1 on effector T cells | Dose–response between hyperglycemia and immune dysregulation | Lacks interventional evidence that improving glycemia restores checkpoint integrity or improves outcomes | [77] |

| Endothelial Checkpoint Expression | 70% reduction in PD-L1 in diabetic endothelium | Suggests vascular tissue participates in immune dysregulation | Functional impact on endothelial-immune cross-talk remains speculative without in vivo confirmation | [78] |

| Treg Checkpoint Functionality | Tregs exhibit a 60% reduction in CTLA-4 expression in diabetic patients | Highlights dysfunction in regulatory arms of immune tolerance | No clinical trials have evaluated whether restoring Treg function alters CV risk in diabetes | [79] |

| Experimental Therapeutic Modulation | Pilot data show that checkpoint restoration reduces inflammation and improves endothelial function | Suggests reversibility and therapeutic targetability of immune dysfunction in diabetes | Limited sample and short duration, with uncertain effects on hard CV outcomes | [80] |

| Checkpoint | Key Functions in Vasculature | Effect of Diabetes | Therapeutic Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD-1/PD-L1 [76] | Suppresses T cell activity, stabilizes plaques | Downregulated in diabetes, increased CD8+ infiltration | PD-L1 agonists, gene upregulation |

| CTLA-4 [77] | Supports Treg suppression of inflammation | Impaired function, reduced expression | CTLA-4 mimetics, Treg-based therapies |

| LAG-3, TIM-3, TIGIT [78] | Emerging regulatory roles in atherogenesis | Poorly characterized | Future targets for intervention |

| Parameter | Design Consideration |

|---|---|

| Population | T2DM patients with subclinical or symptomatic atherosclerosis |

| Intervention | PD-L1 agonist (e.g., mAb, nanoparticle) or CTLA-4 mimetic |

| Control | Placebo or standard care |

| Primary Outcome | MACE (MI, stroke, CV death) |

| Secondary Outcomes | hsCRP, IL-6, T cell activation, plaque composition (imaging) |

| Biomarkers | sPD-L1, CD8+/PD-1+ ratios, Treg/Th17 balance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saha, D.; Dutta, P.; Chakraborty, A. Immune Checkpoint Restoration as a Therapeutic Strategy to Halt Diabetes-Driven Atherosclerosis. Biology 2025, 14, 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121731

Saha D, Dutta P, Chakraborty A. Immune Checkpoint Restoration as a Therapeutic Strategy to Halt Diabetes-Driven Atherosclerosis. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121731

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaha, Dwaipayan, Preyangsee Dutta, and Abhijit Chakraborty. 2025. "Immune Checkpoint Restoration as a Therapeutic Strategy to Halt Diabetes-Driven Atherosclerosis" Biology 14, no. 12: 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121731

APA StyleSaha, D., Dutta, P., & Chakraborty, A. (2025). Immune Checkpoint Restoration as a Therapeutic Strategy to Halt Diabetes-Driven Atherosclerosis. Biology, 14(12), 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121731