Modeling Dominant Macrobenthic Species Distribution and Predicting Potential Habitats in the Yellow River Estuary, China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

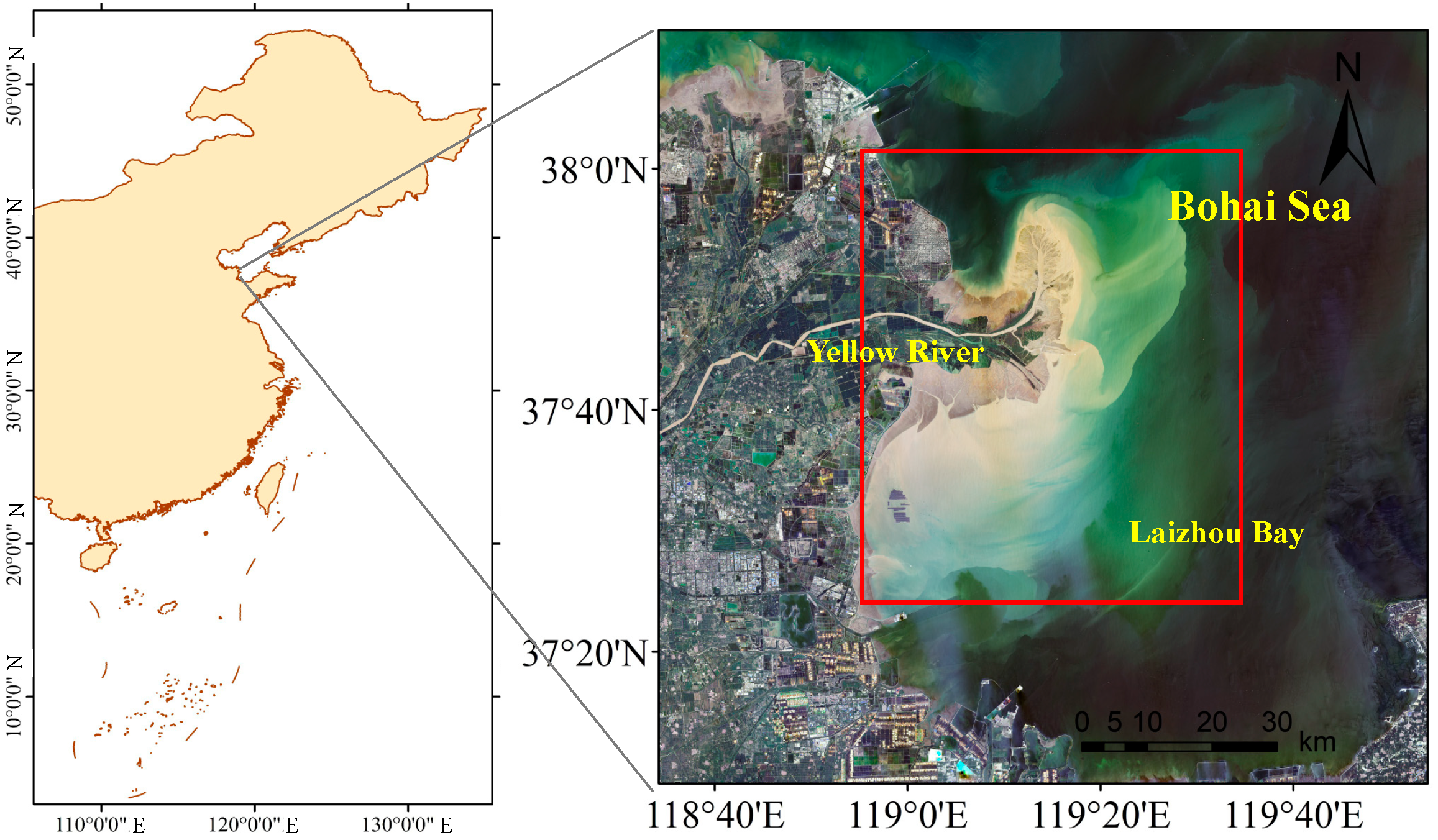

2.1. Field Survey and Data Collection

2.2. Analysis of Dominant Macrobenthic Species

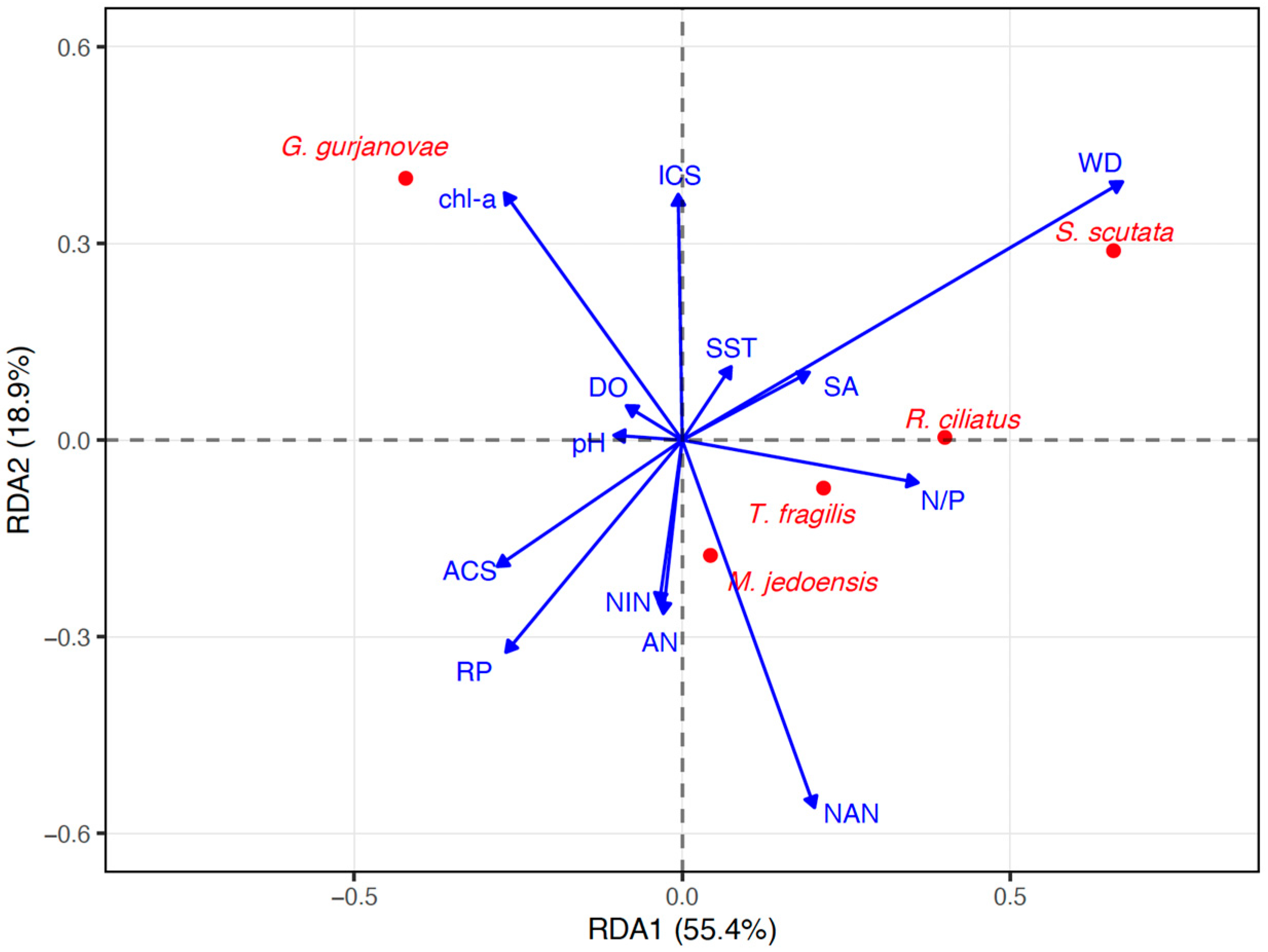

2.3. Redundancy Analysis Between Dominant Species and Environmental Variables

2.4. Construction of Species Distribution Models Using BRT

2.4.1. Introduction to the BRT Model

2.4.2. Selection of Model Parameters

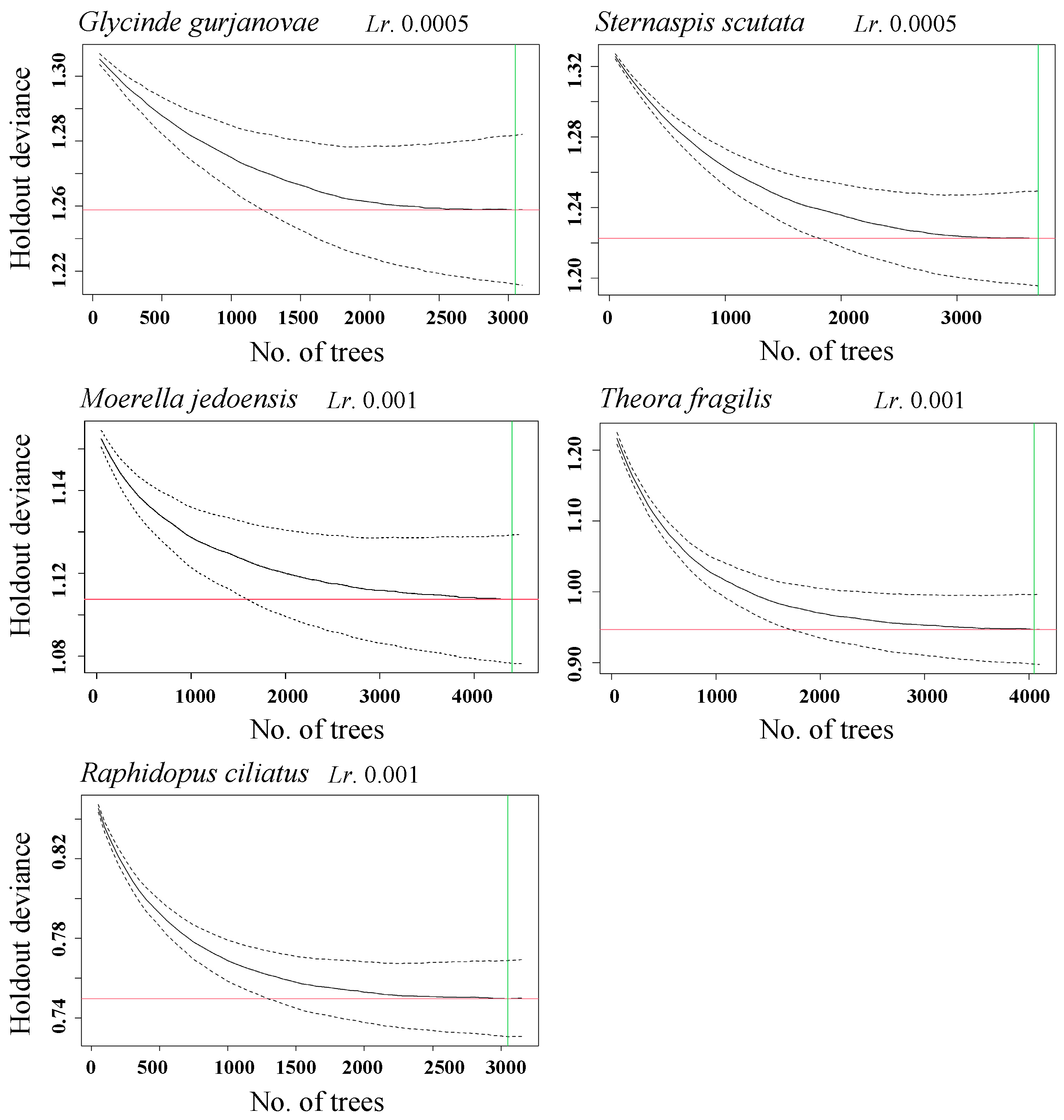

2.4.3. Optimal Number of Decision Trees

2.4.4. Calculation of Predictor Importance

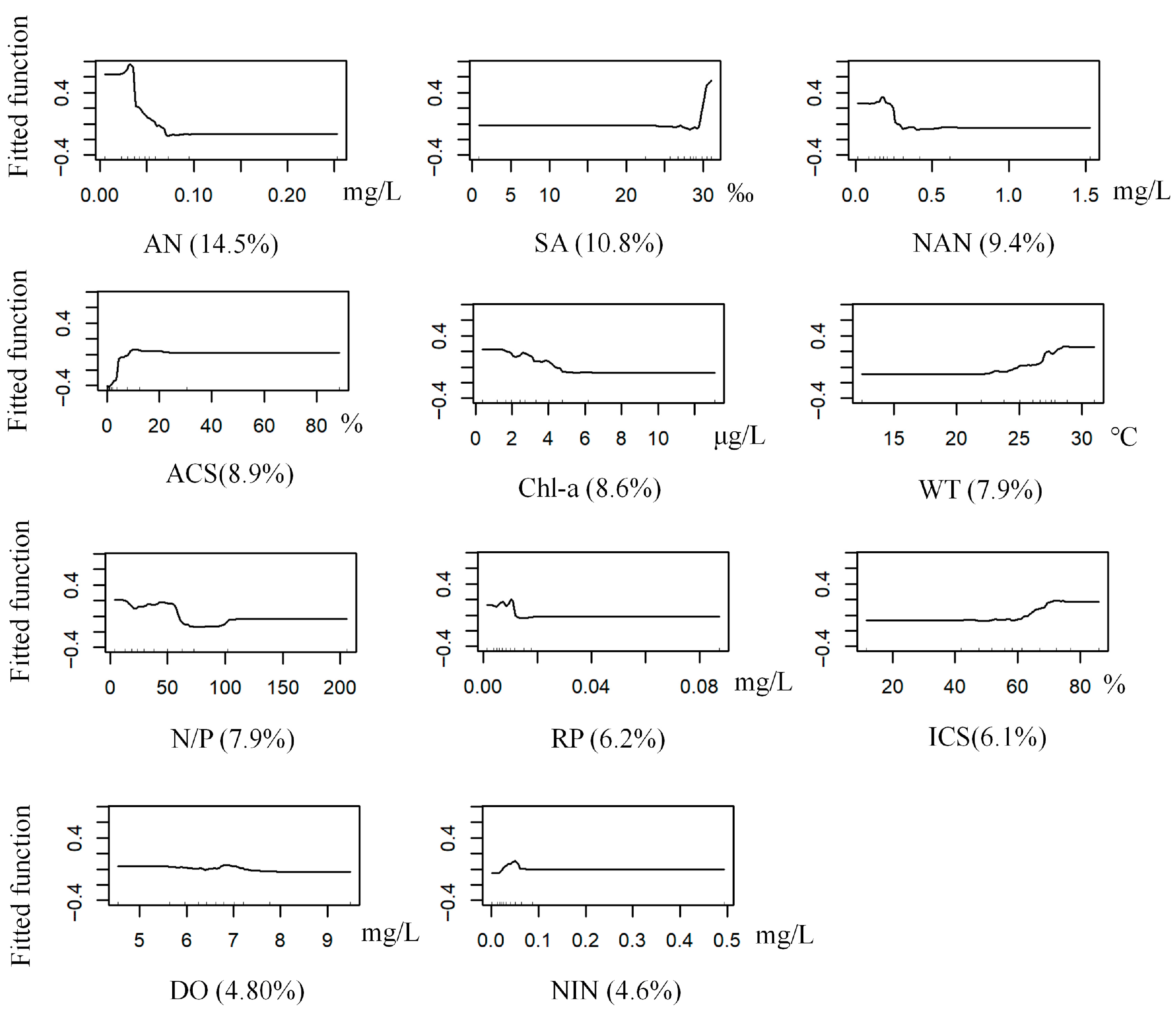

2.4.5. Performance Evaluation and Validation of the Predictive Model

2.5. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Occurrence Probability of Dominant Macrobenthic Species

3. Results

3.1. Dominant Macrobenthic Species

3.2. Relationships Between Dominant Macrobenthic Species Distribution and Environmental Variables

3.3. BRT Modeling of Dominant Macrobenthic Species Distribution

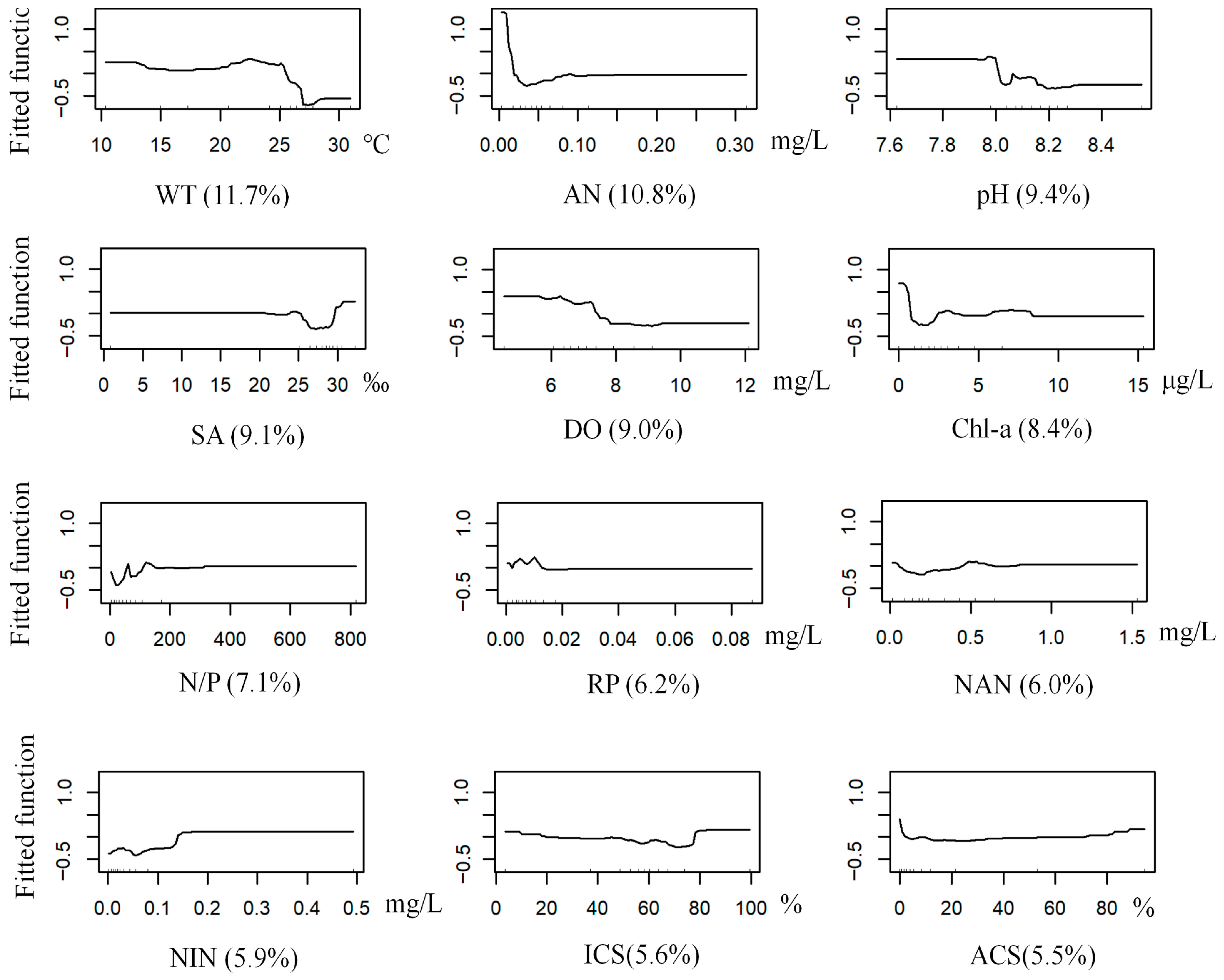

3.3.1. G. gurjanovae

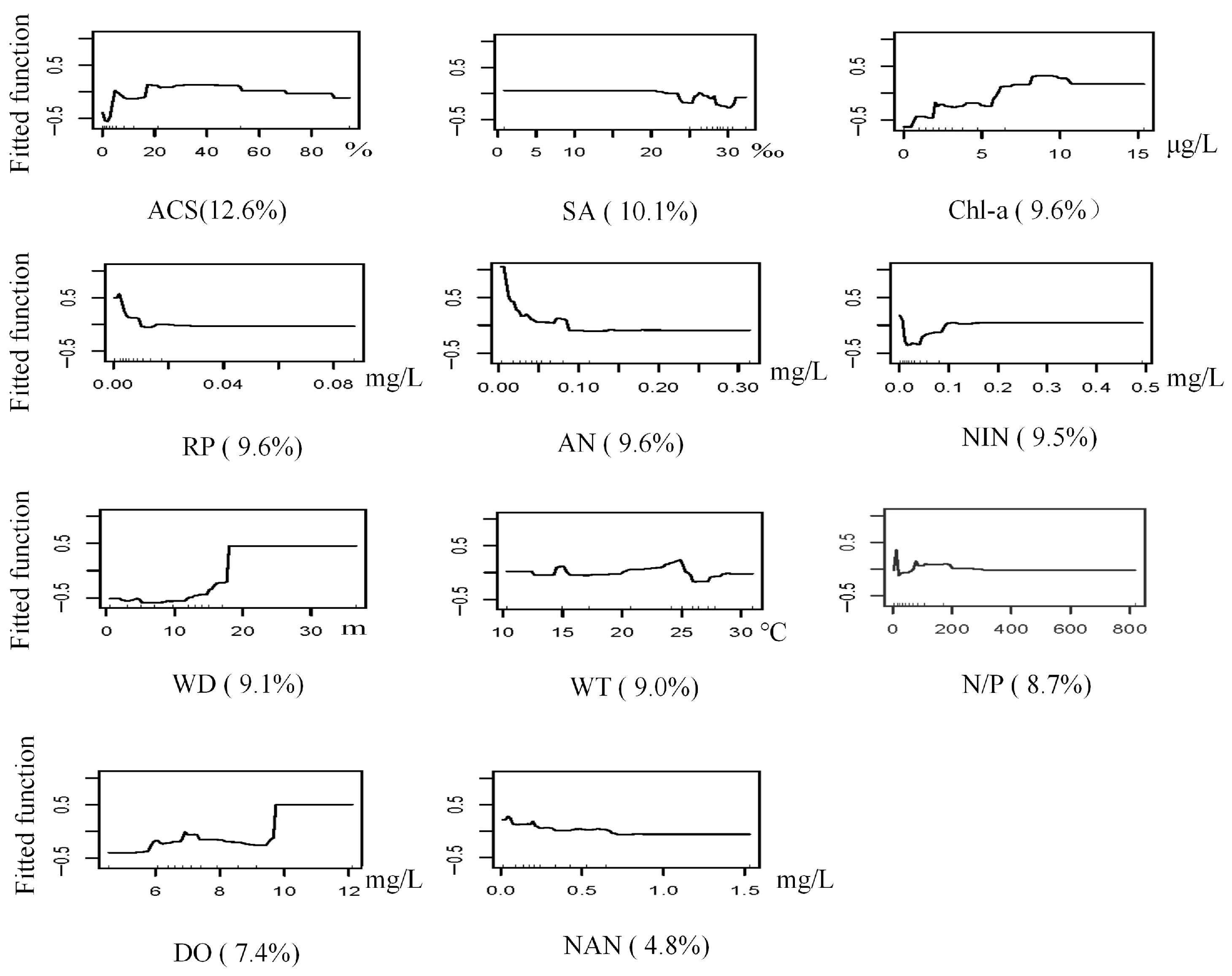

3.3.2. S. scutate

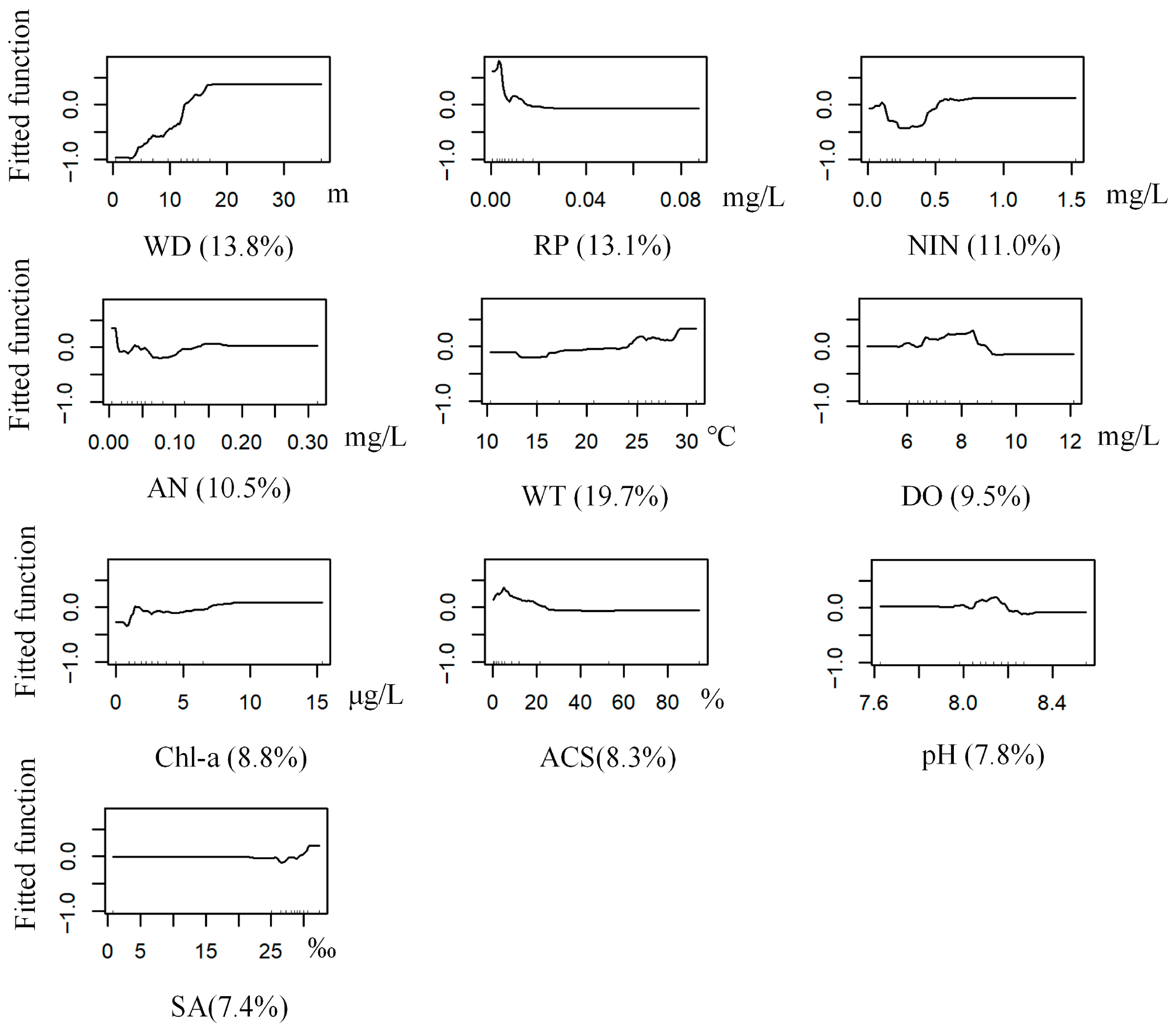

3.3.3. M. jedoensis

3.3.4. T. fragilis

3.3.5. R. ciliates

3.4. Spatio-Temporal Variation in the Predicted Occurrence Probability of Macrobenthic Species

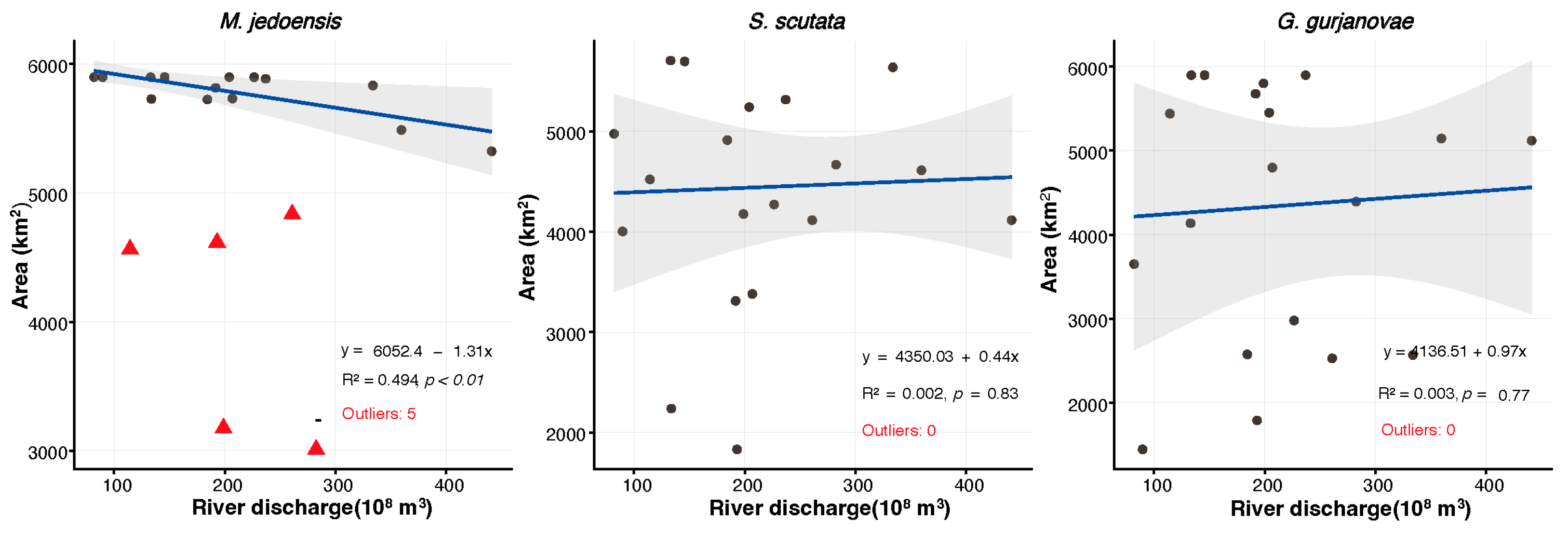

3.5. Influence of Yellow River Annual Discharge on the Distribution of Macrobenthic Species

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationships Between Macrobenthic Fauna Distribution and Environmental Drivers

4.2. Model Limitations and Optimization Directions

4.3. Implications for Management

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Odum, E.P. The Strategy of Ecosystem Development. Science 1969, 164, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Isbell, F.; Cowles, J.M. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2014, 45, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Du, E.; Eisenhauer, N.; Mathieu, J.; Chu, C. Global Engineering Effects of Soil Invertebrates on Ecosystem Functions. Nature 2025, 640, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, G.-R.; Post, E.; Convey, P.; Menzel, A.; Parmesan, C.; Beebee, T.J.C.; Fromentin, J.-M.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Bairlein, F. Ecological Responses to Recent Climate Change. Nature 2002, 416, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmesan, C. Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2006, 37, 637–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsky, M.L.; Selden, R.L.; Kitchel, Z.J. Climate-Driven Shifts in Marine Species Ranges: Scaling from Organisms to Communities. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2020, 12, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotze, H.K.; Lenihan, H.S.; Bourque, B.J.; Bradbury, R.H.; Cooke, R.G.; Kay, M.C.; Kidwell, S.M.; Kirby, M.X.; Peterson, C.H.; Jackson, J.B.C. Depletion, Degradation, and Recovery Potential of Estuaries and Coastal Seas. Science 2006, 312, 1806–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, M.J.; Tsai, P.; Wong, P.S.; Cheung, A.K.L.; Basher, Z.; Chaudhary, C. Marine Biogeographic Realms and Species Endemicity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P. Aquatic Biodiversity and Sustainable Development of Estuaries; Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 2008; pp. 1–313. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. Characteristics and Ecosystem Health Evaluation Research of the Yellow River Delta Wetland. Master’s Thesis, North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Saito, Y.; Liu, J.P.; Sun, X. Interannual and Seasonal Variation of the Huanghe (Yellow River) Water Discharge over the Past 50 Years: Connections to Impacts from ENSO Events and Dams. Glob. Planet. Change 2006, 50, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, G.; Qiao, L.; Shi, J.; Dong, P.; Xu, J.; Ma, Y. Long-Term Evolution in the Location, Propagation, and Magnitude of the Tidal Shear Front off the Yellow River Mouth. Cont. Shelf Res. 2017, 137, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Shan, X.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Cui, Y.; Zuo, T. Long-Term Changes in the Fishery Ecosystem Structure of Laizhou Bay, China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2013, 56, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Sun, P.; Jin, X.; Li, X.; Dai, F. Long-Term Changes in Fish Assemblage Structure in the Yellow River Estuary Ecosystem, China. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2013, 5, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Fang, Y.; Li, H.-S. Ecology of Benthic Animals; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2024; pp. 1–352. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Z. Macrobethic Community Structure in the Southern and Central Bohai Sea, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2004, 24, 531–537, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cong, J.-Y.; Li, X.-Z.; Xu, Y. Application of Species Distribution Models in Predicting the Distribution of Marine Macrobenthos. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 35, 2392–2400, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Tu, L.; Yü, Z. Preliminary study on the macrofauna in the Huanghe River estuary and its adjacent waters (I) the biomass. J. Ocean Univ. Qingdao 1990, 20, 37–45, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Luo, X.; Zhang, J.; Lin, S.; Wang, X. The Assessment of Benthic Community Health and Habitat Suitability in Huanghe Estuary and Its Adjacent Area. Period. Ocean Univ. China 2015, 45, 107–112, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Chen, L.; Lv, J.; Jiang, S.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Song, B.; Li, B. Community Characteristics of Macrobenthos in the Coastal Waters of the Yellow River Estuary. Guangxi Sci. 2020, 27, 231–240, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Long, S.; Xiu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M. Influence of Water Quality on Community Structure of Zoobenthos in the Yellow River Delta. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2022, 42, 104–110, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; Xie, T.; Ning, Z.; Cui, B. Characteristic Change of Macrobenthic Communities in the Tidal Flat Wetlands of the Yellow River Delta in the Past 20 Years. Environ. Eng. 2024, 42, 42–50, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Lv, Z. Effects of Water and Sediment Discharge Regulation on Macrobenthic Community in the Yellow River Estuary. Res. Environ. Sci. 2015, 28, 259–266, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S.; Yang, Y.; Xu, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Li, F.; Yu, H. How the Water-Sediment Regulation Scheme in the Yellow River Affected the Estuary Ecosystem in the Last 10 Years? Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, J.; Fu, Q.; Chen, L.; Chen, J.; Sun, T.; Li, B. Artificial River Flow Regulation Triggered Spatio-Temporal Changes in Marine Macrobenthos of the Yellow River Estuary. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 202, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, C.M.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Bao, M.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Du, J.; Gao, Y.; Hu, L.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Qin, G. Advances of Marine Biogeography in China: Species Distribution Model and Its Applications. Biodivers. Sci. 2024, 32, 23453, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Leathwick, J.R.; Hastie, T. A Working Guide to Boosted Regression Trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 2008, 77, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, T.J.; Morrison, M.A.; Leathwick, J.R.; Carbines, G.D. Ontogenetic Habitat Associations of a Demersal Fish Species, Pagrus auratus, Identified Using Boosted Regression Trees. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 462, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froeschke, B.F.; Tissot, P.; Stunz, G.W.; Froeschke, J.T. Spatiotemporal Predictive Models for Juvenile Southern Flounder in Texas Estuaries. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2013, 33, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, W.C.; Mehner, T.; Ritterbusch, D.; Brämick, U. The Influence of Anthropogenic Shoreline Changes on the Littoral Abundance of Fish Species in German Lowland Lakes Varying in Depth as Determined by Boosted Regression Trees. Hydrobiologia 2014, 724, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soykan, C.U.; Eguchi, T.; Kohin, S.; Dewar, H. Prediction of Fishing Effort Distributions Using Boosted Regression Trees. Ecol. Appl. 2014, 24, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 12763.4-2007; The Specification for Oceanographic Survey—Part 4: Survey of Chemical Parameters in Sea Water. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- GB/T 12763.6-2007; Specifications for Oceanographic Survey—Part 6: Marine Biological Survey. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- GB/T 12763.9-2007; Specifications for Oceanographic Survey—Part 9: Guidelines for Marine Ecological Survey. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Pinkas, L.; Oliphant, M.S.; Iverson, I.L. Food Habits of Albacore, Bluefin Tuna, and Bonito in California Waters. Fish Bull. 1970, 152. [Google Scholar]

- Lawesson, J.E. Statistical Methods for Addressing Collinearity in Regression Models: A Review of Recent Developments and Applications. J. Biometr. Biostat. 2010, 1, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and Regression Trees; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J.H. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.H. Stochastic Gradient Boosting. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2002, 38, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swets, J.A. Measuring the Accuracy of Diagnostic Systems. Science 1988, 240, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, G. Generalized Boosted Regression Models: A Guide to the GBM Package. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gbm/vignettes/gbm.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Hyndman, R.J.; Koehler, A.B. Another Look at Measures of Forecast Accuracy. Int. J. Forecast. 2006, 22, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, E.; Ronchetti, E. Robust Inference for Generalized Linear Models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2001, 96, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsley, D.A.; Kuh, E.; Welsch, R.E. Regression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thrush, S.F.; Dayton, P.K. Disturbance to Marine Benthic Habitats by Trawling and Dredging: Implications for Marine Biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2002, 33, 449–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Zhong, Z.; Yu, S.; Sui, X.; Yao, X.; Zou, L. The Current Status and 20 Years of Evolution of Nutrient Structure in the Yellow River Estuary. Prog. Fish. Sci. 2024, 45, 1–13, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.-C. Study on the Hydro-Morphodynamic in the Tidal Changjiang River. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads, D.C.; Young, D.K. The Influence of Deposit-Feeding Organisms on Sediment Stability and Community Trophic Structure. J. Mar. Res. 1970, 28, 150–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tan, S.Z.; Chen, S.S.; Zhou, H.H.; Ji, X.; Cai, Y.R.; Ji, H.H.; Yang, X.X.; Fan, H.M.; Deng, B.P. The variation of macrobenthos community structure in Changjiang River estuary from 2011 to 2020. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 5863–5874, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Sui, J.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B. Potential impacts of climate change on the distribution of echinoderms in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 194, 115246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja, A.; Franco, J.; Pérez, V. A Marine Biotic Index to Establish the Ecological Quality of Soft-Bottom Benthos Within European Estuarine and Coastal Environments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 40, 1100–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.-Q.; Liu, L.-S.; Qiao, F.; Lin, K.-X.; Zhou, J. Study on the Changes of Macrobenthos Communities and Their Causes in Bohai Bay. Environ. Sci. 2012, 33, 3104–3109, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G.; Wang, J.; Ke, H.; Dong, G.; Du, X. Study on the Variation Trend of the Influence of Yellow River Runoff on the Water Environment in the Estuary and Adjacent Sea Areas. Open J. Fish. Res. 2021, 8, 17–33, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, M.; Marinho, N.; Costa, L.; Nascimento, E.; Ferreira, G.; Santos, P. Terrestrial Input Impacts on the Yellow River Estuary Ecosystem: A Review. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2024, 295, 108890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, J. Characteristics of Bivalve Diversity in Typical Habitats of China Seas. Biodivers. Sci. 2011, 19, 716, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.S.; Liu, Z.H.; Ma, P.Z.; Sun, X.J.; Zhou, L.Q.; Li, Z.Z.; Xu, D.; Wu, B. Species Composition and Community Characteristics of Typical Intertidal Shellfish in Qingdao, China. Prog. Fish. Sci. 2025, 46, 15–29, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Ding, X.; Hou, X.; Wu, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, N.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, D.; Liu, C.; et al. Temporal and Spatial Variations of Chlorophyll a and Their Influencing Factors in the Bohai Sea. Period. Ocean Univ. China 2023, 53, 123–131, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Lai, Z.; Jiang, W.; Gao, Y.; Pang, S.; Yang, W. Study on Community Structure of Macrozoobenthos and Impact Factors in Pearl River Estuary. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2010, 34, 1179–1188, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Meng, W.; Tian, Z.; Cai, Y. Distribution and variation of macrobenthos from the Changjiang Estuary and its adjacent waters. Acta. Ecol. Sin. 2008, 28, 3027–3034, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Somero, G.N. Linking Biogeography to Physiology: Evolutionary and Acclimatory Adjustments of Thermal Limits. Front. Zool. 2005, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A. Costs and Consequences of Evolutionary Temperature Adaptation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Wang, J.; Sun, D.; Chi, J.; Fan, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, L. Environmental Heterogeneity Drives the Spatial Distribution of Macrobenthos in the Yellow River Delta Wetland. Aquat. Sci. 2025, 87, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Chagaris, D.; Paperno, R.; Markwith, S. Tropical Estuarine Ecosystem Change Under the Interacting Influences of Future Climate and Ecosystem Restoration. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 5850–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Chai, F.; Huang, D.; Xue, H.; Chen, J.; Xiu, P.; Xuan, J.; Li, J.; Zeng, D.; Ni, X.; et al. Investigation of Hypoxia off the Changjiang Estuary Using a Coupled Model of ROMS-CoSiNE. Prog. Oceanogr. 2017, 159, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Xu, R.; Pan, S.; Yao, Y.; Bian, Z.; Cai, W.-J.; Hopkinson, C.S.; Justic, D.; Lohrenz, S.; Lu, C.; et al. Long-Term Trajectory of Nitrogen Loading and Delivery from Mississippi River Basin to the Gulf of Mexico. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2020, 34, e2019GB006475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Species | Predictor Variables |

|---|---|

| S. scutata, T. fragilis, R. ciliatus | WD, DO, SA, RP, NIN, NAN, AN, chl-a, N/P, pH, WT, ACS |

| M. jedoensis | WD, DO, SA, RP, NIN, NAN, AN, chl-a, N/P, WT, ACS |

| G. gurjanovae | WD, DO, SA, RP, NIN, NAN, AN, chl-a, N/P, WT, ACS, ICS |

| Species | LR | TC | No. of Trees | BF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G. gurjanovae | 0.0005 | 5 | 1800 | 0.5 |

| S. scutata | 0.005 | 15 | 3700 | 0.5 |

| M. jedoensis | 0.001 | 5 | 4400 | 0.5 |

| T. fragilis | 0.001 | 5 | 4020 | 0.5 |

| R. ciliatus | 0.001 | 5 | 3050 | 0.5 |

| Species | Training AUC | CV AUC | RMSE | MAE | MD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G. gurjanovae | 0.96 | 0.73 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 1.18 |

| S. scutata | 0.97 | 0.75 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 1.11 |

| M. jedoensis | 0.96 | 0.71 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 1.19 |

| T. fragilis | 0.99 | 0.78 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.91 |

| R. ciliatus | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, C.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Yu, H.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, S.; Sun, J.; Shang, Y.; et al. Modeling Dominant Macrobenthic Species Distribution and Predicting Potential Habitats in the Yellow River Estuary, China. Biology 2025, 14, 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121732

Yuan C, Huang J, Wang L, Zhang T, Yu H, Sun H, Liu Y, Sun S, Sun J, Shang Y, et al. Modeling Dominant Macrobenthic Species Distribution and Predicting Potential Habitats in the Yellow River Estuary, China. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121732

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Chao, Juan Huang, Lan Wang, Tao Zhang, Haolin Yu, Huiying Sun, Yumeng Liu, Shuo Sun, Jingyi Sun, Yongjun Shang, and et al. 2025. "Modeling Dominant Macrobenthic Species Distribution and Predicting Potential Habitats in the Yellow River Estuary, China" Biology 14, no. 12: 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121732

APA StyleYuan, C., Huang, J., Wang, L., Zhang, T., Yu, H., Sun, H., Liu, Y., Sun, S., Sun, J., Shang, Y., Feng, J., & Xu, J. (2025). Modeling Dominant Macrobenthic Species Distribution and Predicting Potential Habitats in the Yellow River Estuary, China. Biology, 14(12), 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121732