From Seed to Young Plant: A Study on Germination and Morphological Characteristics of Crateva tapia L. (Capparaceae)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Water Content

2.2. Fruit and Seed Biometrics

2.3. Fruit Morphology

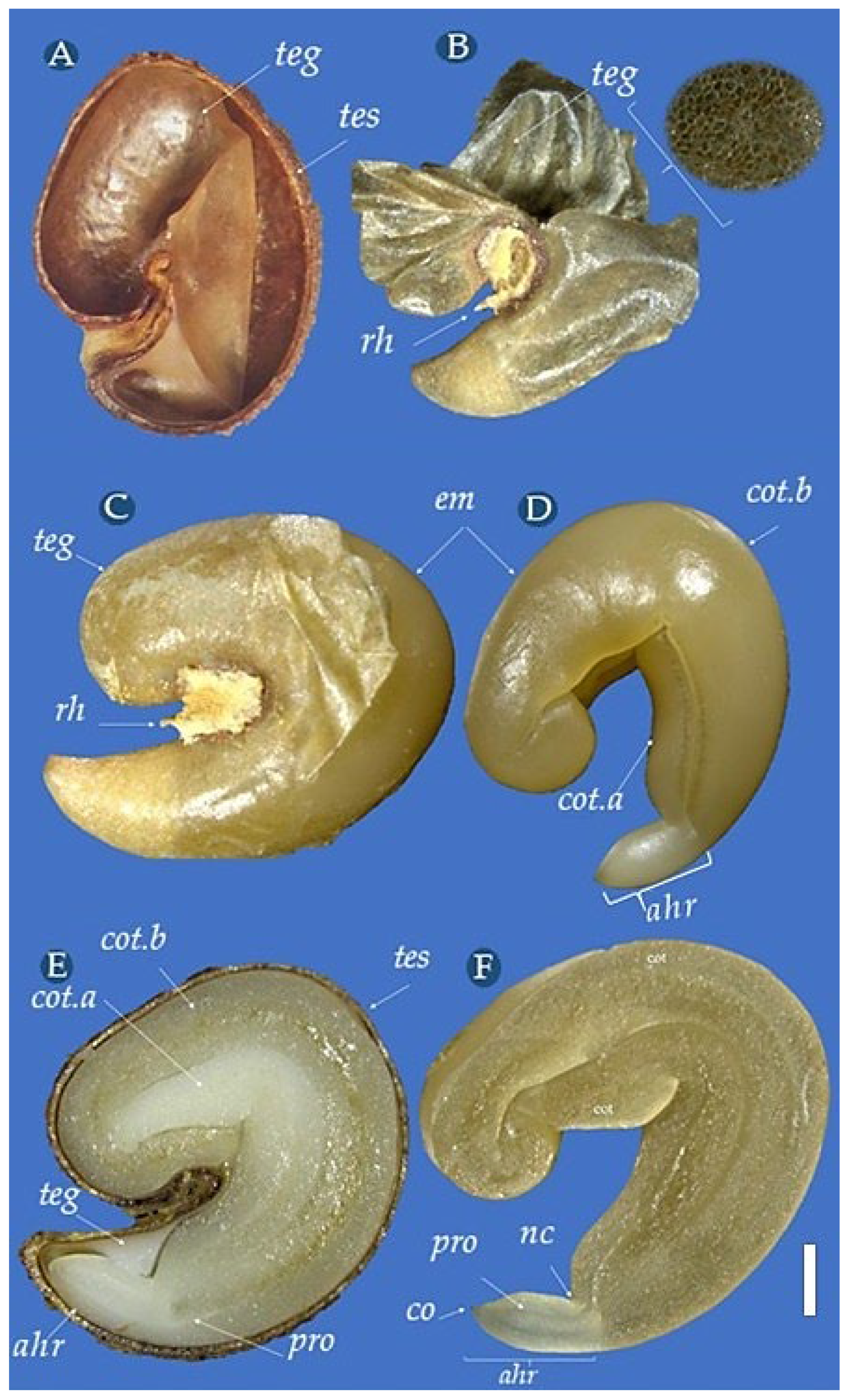

2.4. Seed Morphology

2.5. Water Absorption Curve

2.6. Germination Curve and Normal Seedling Development

2.7. Morphological Description of Germination, Seedling, and Young Plant

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

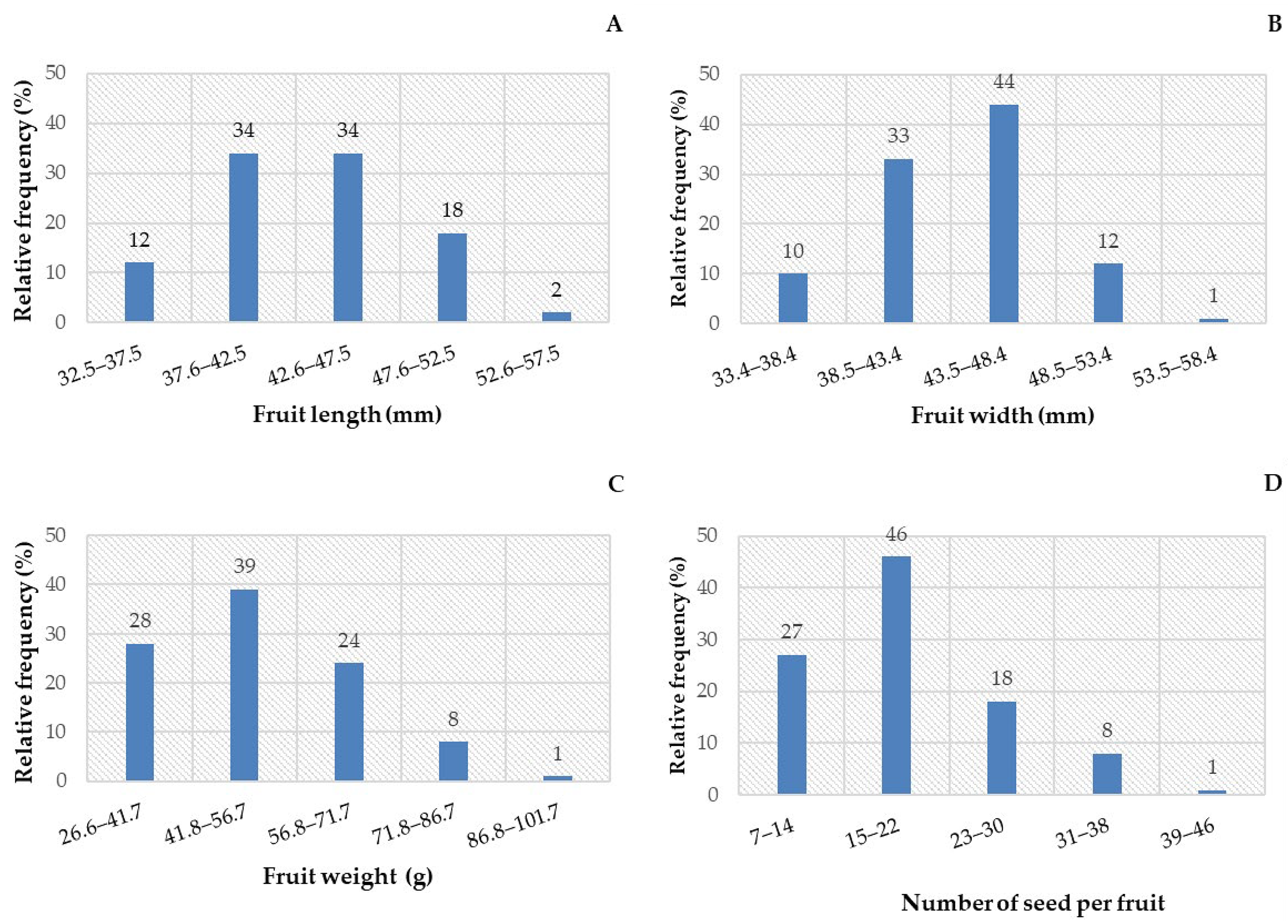

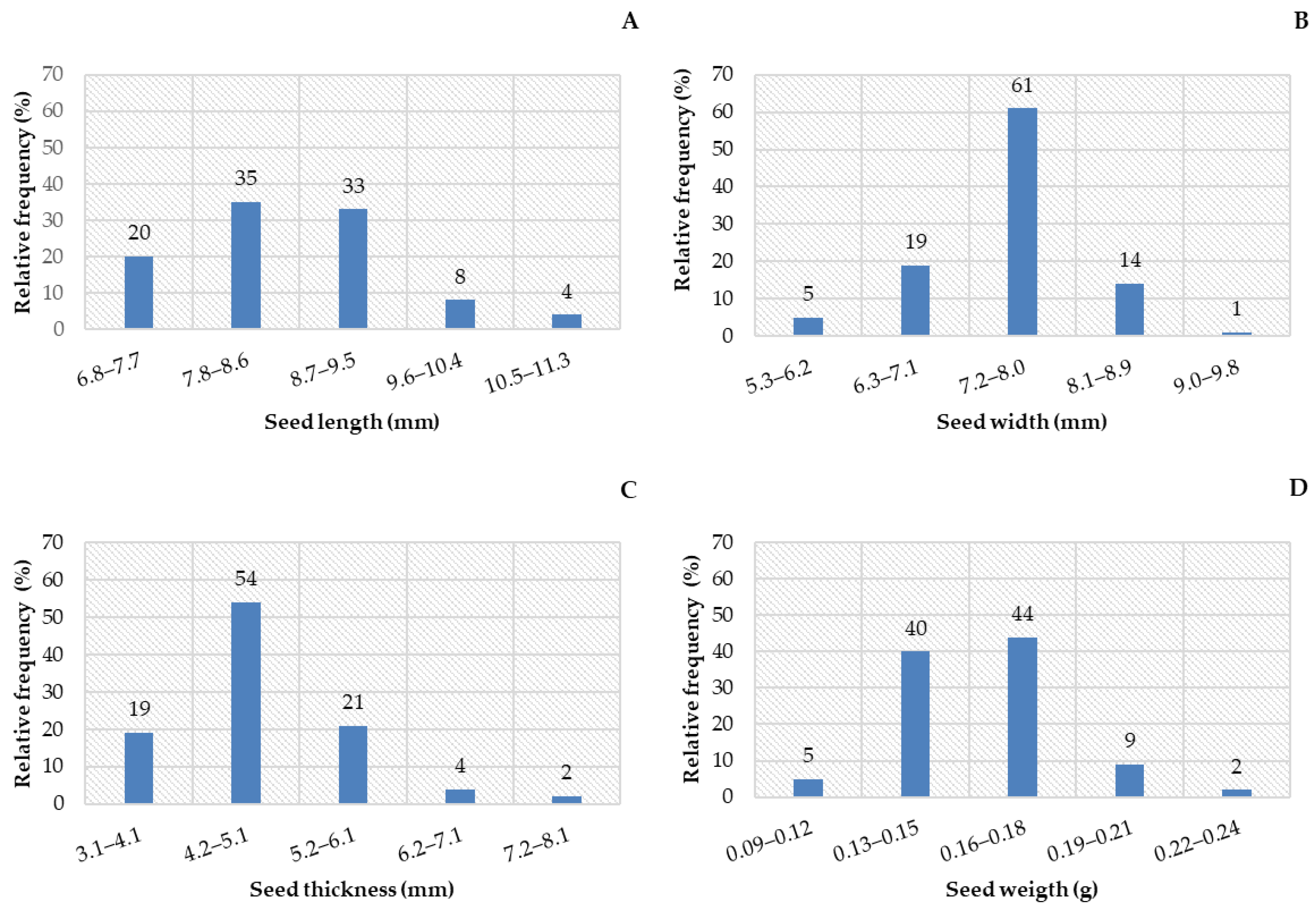

3.1. Biometrics of Fruits and Seeds

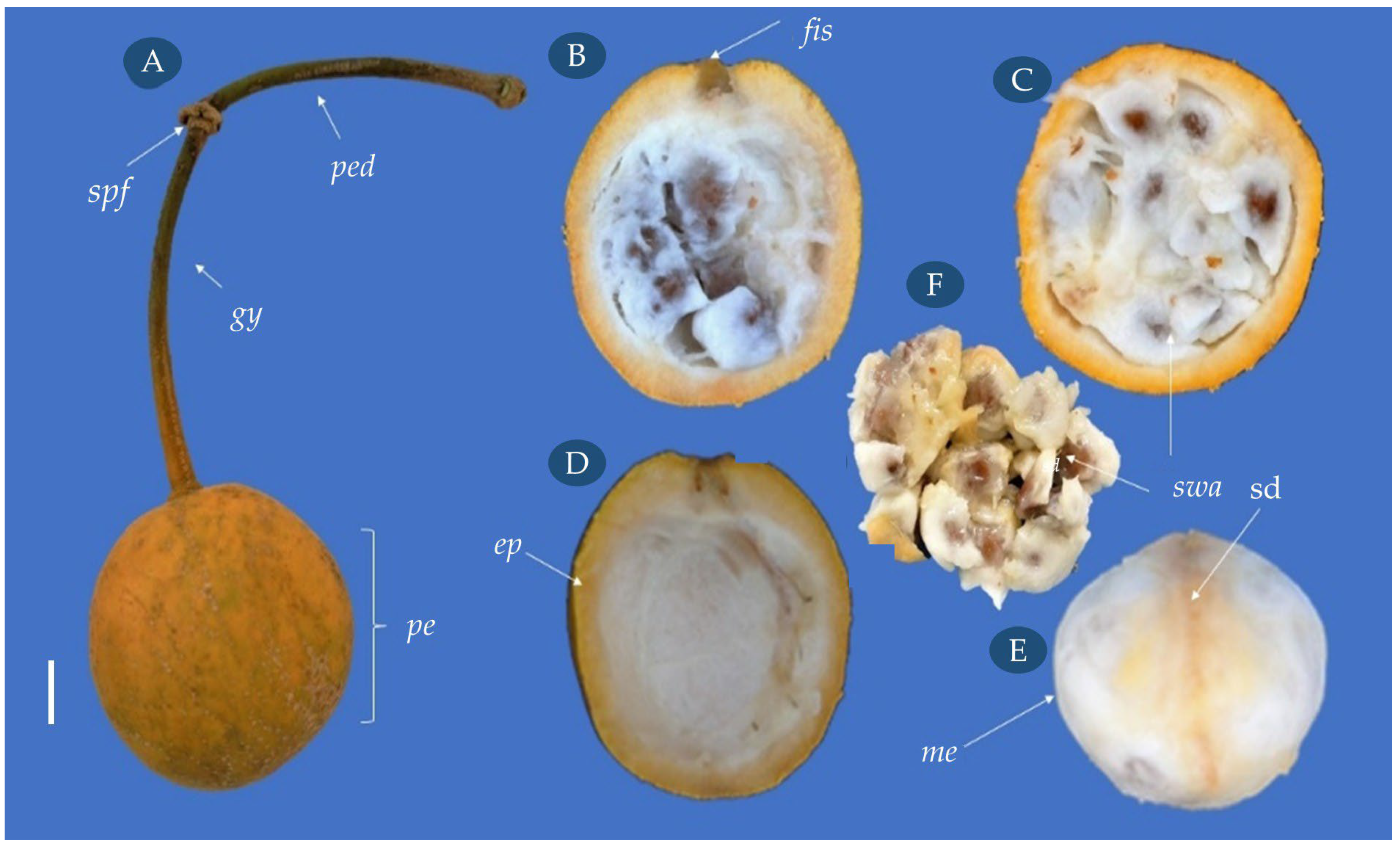

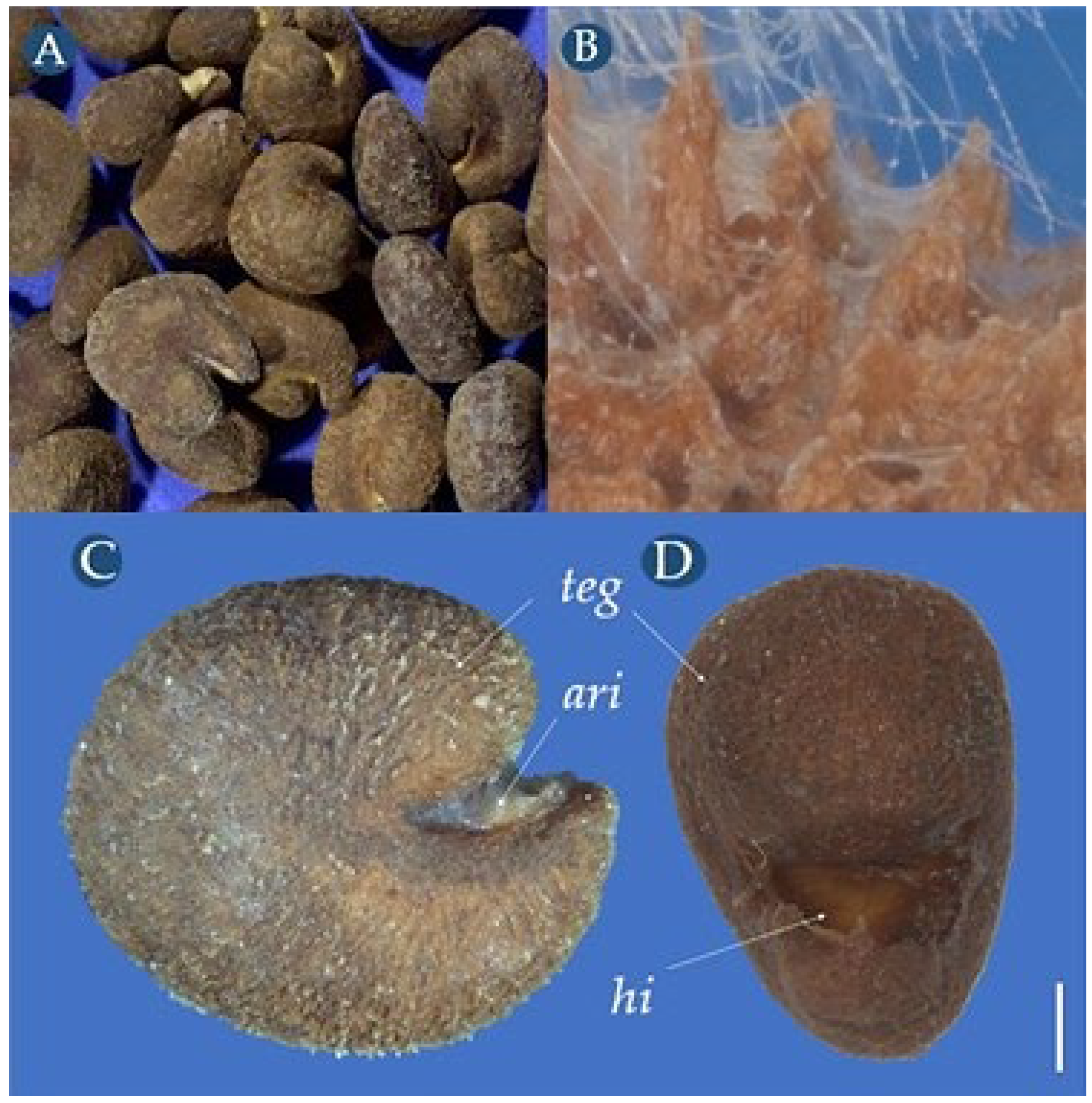

3.2. Morphological Aspects of the Fruit and Seed

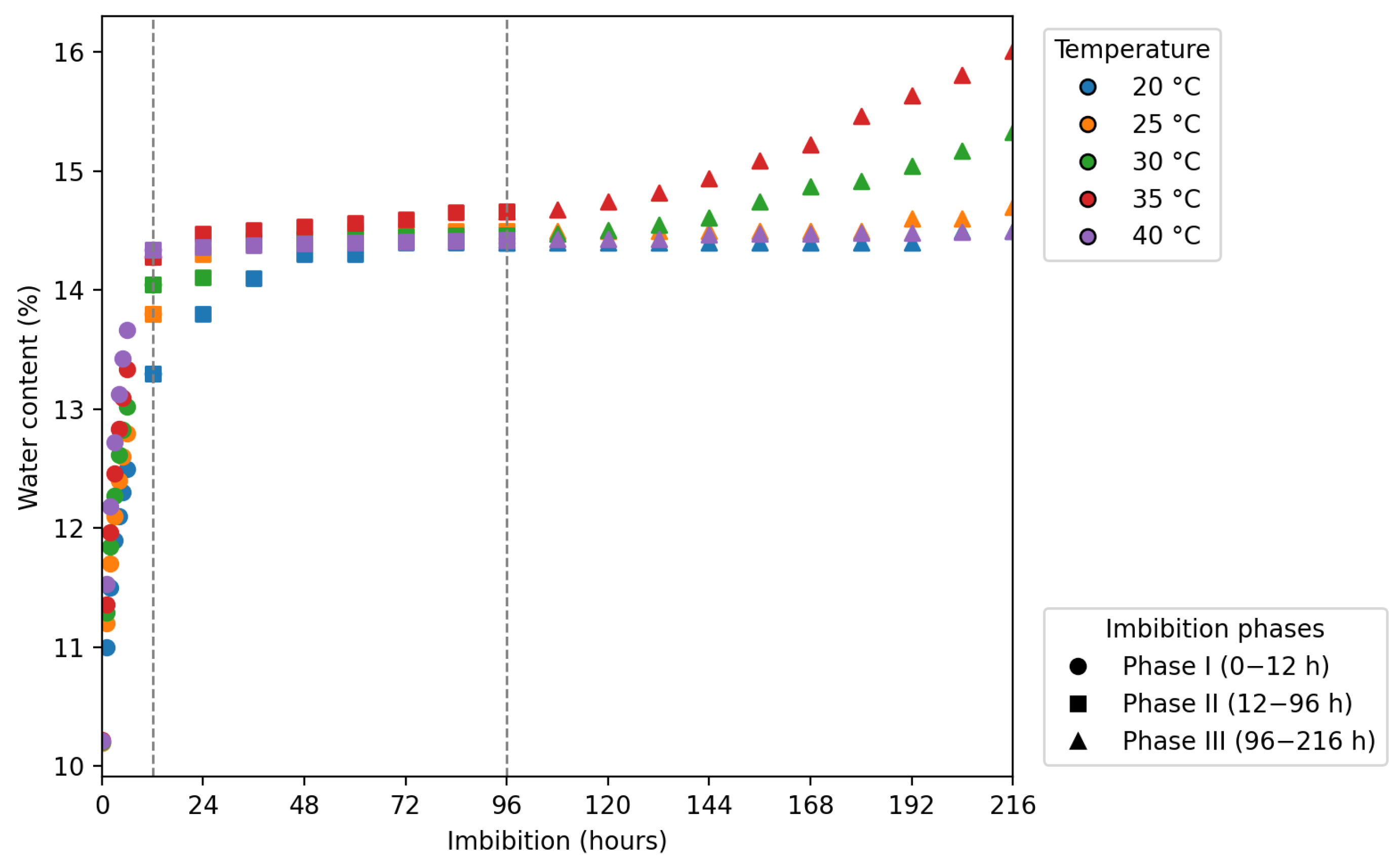

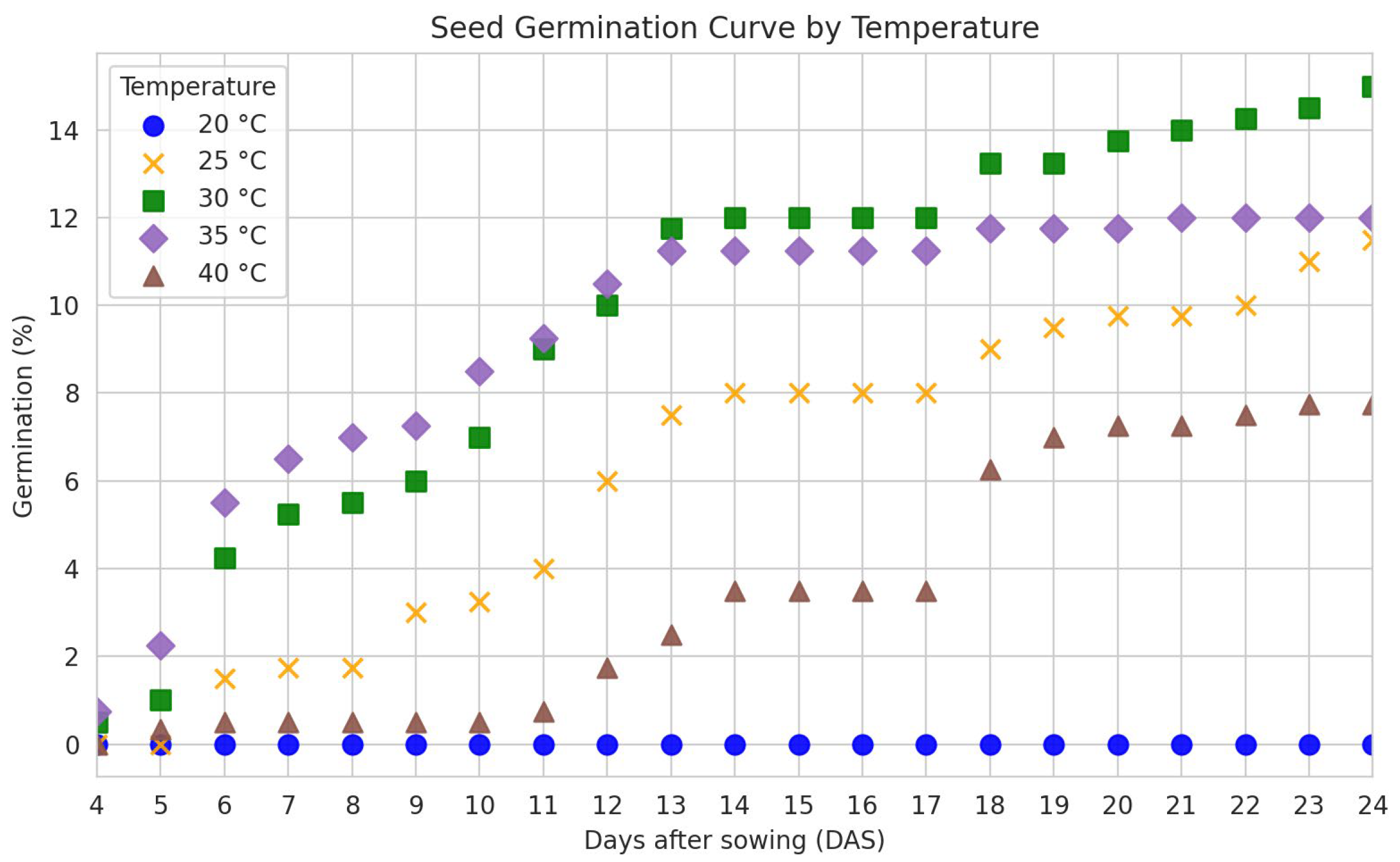

3.3. Water Absorption Curve and Seed Germination

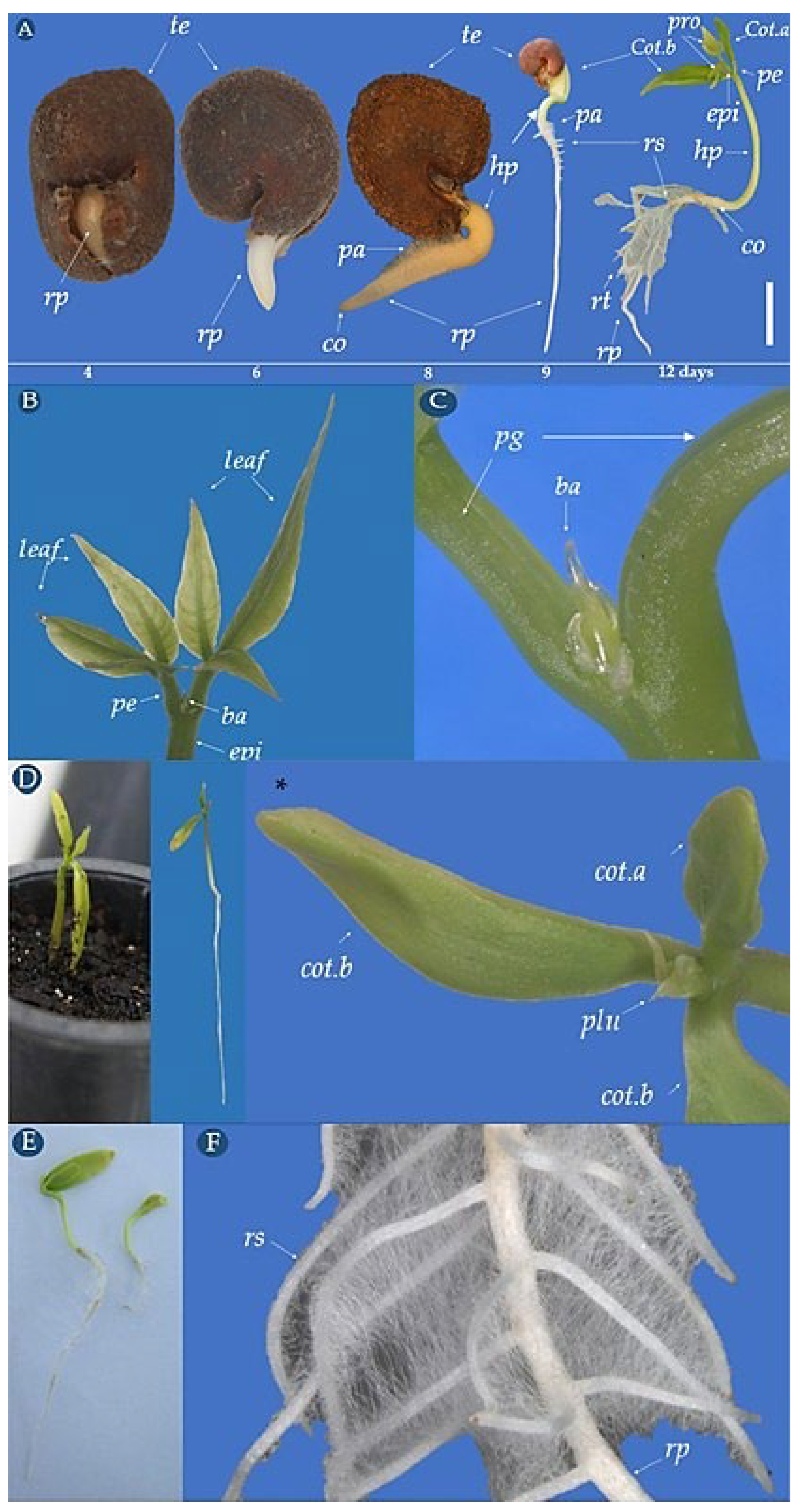

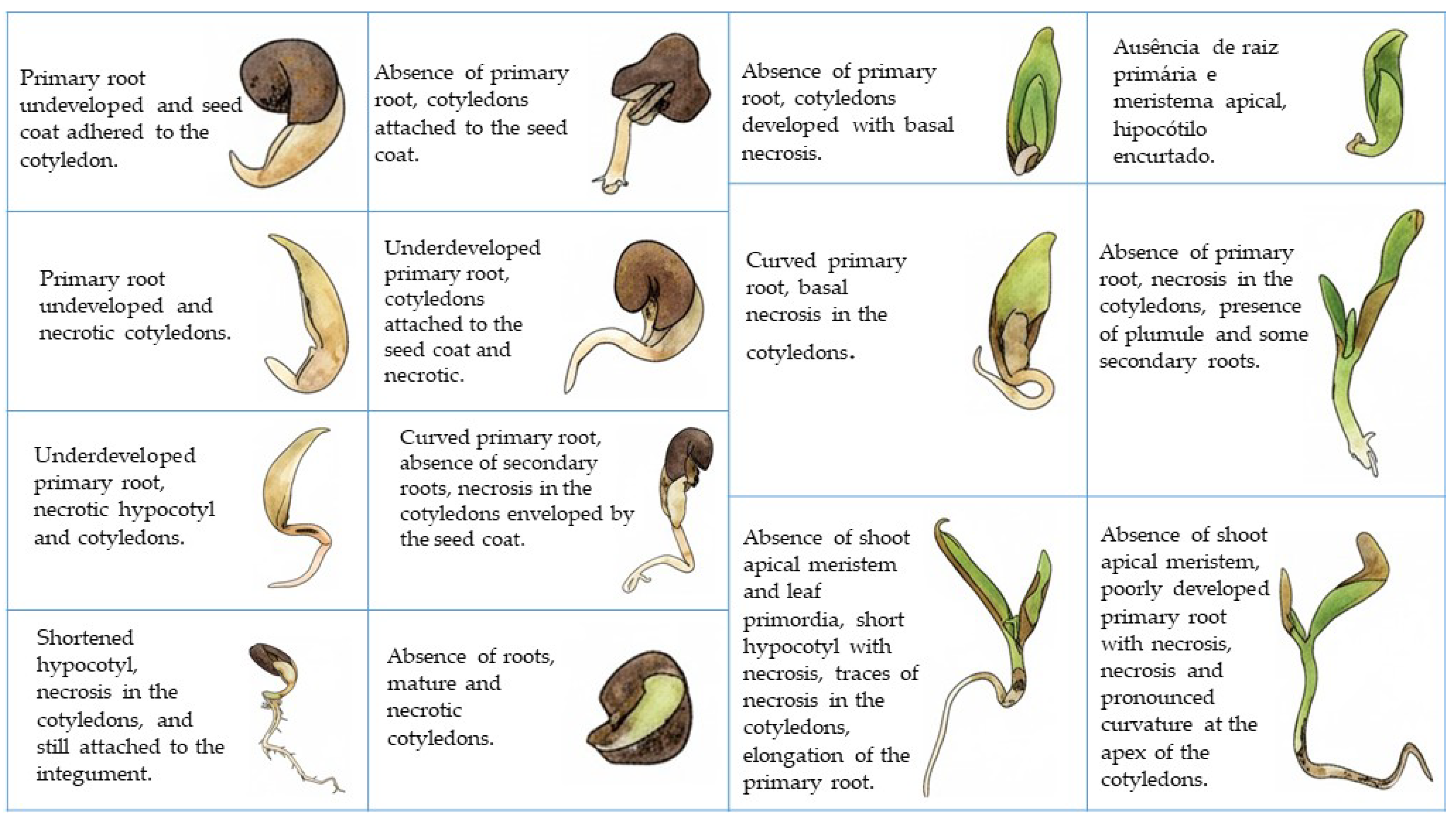

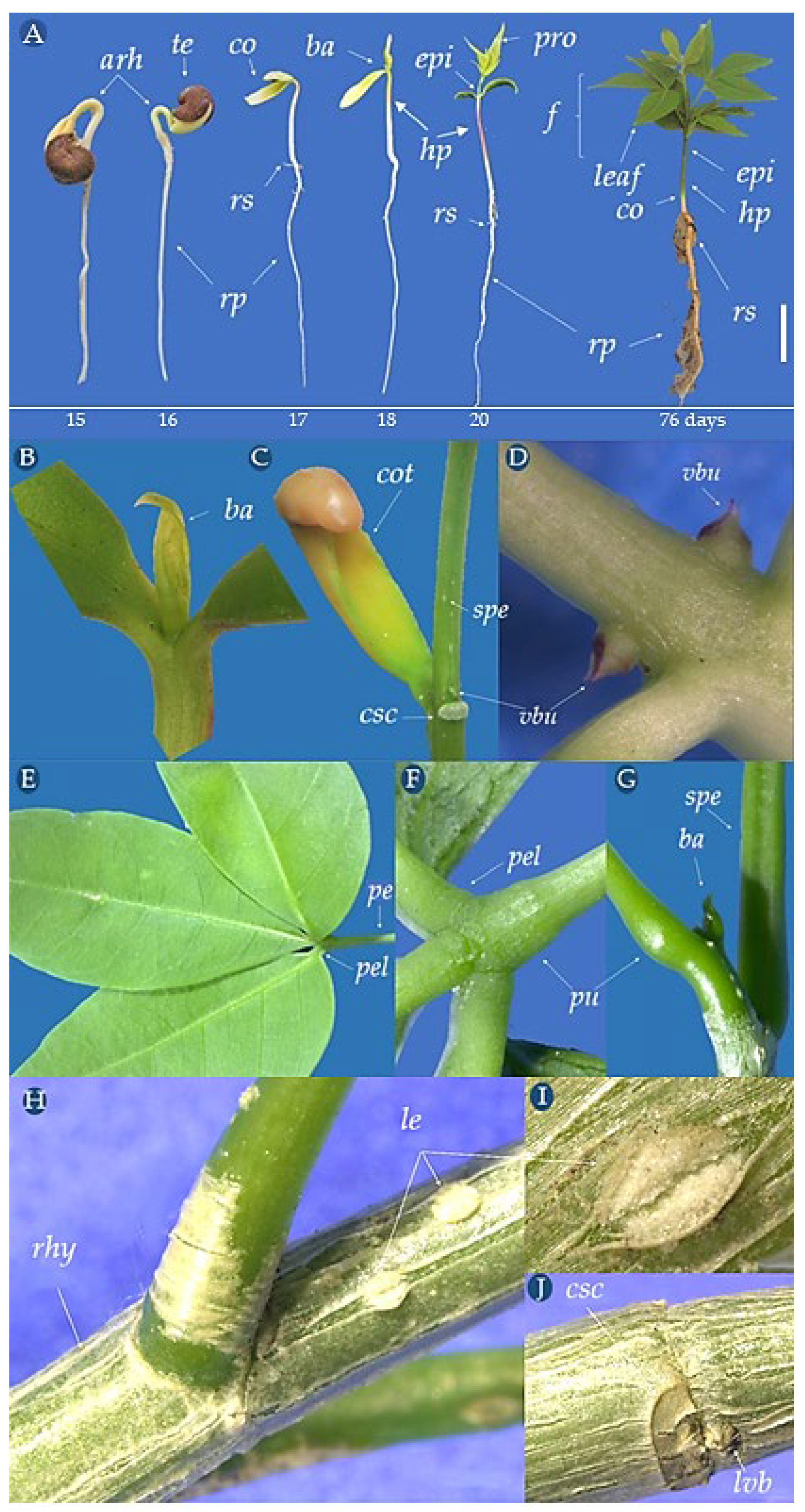

3.4. Germination, Normal, Abnormal Seedling, and Young Plant Morphology

3.5. Morphological Aspects of C. tapia Young Plant

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loiola, M.I.B.; Souza, S.S.G. Ampliando o conhecimento sobre a flora fanerogâmica do Ceará. Bol. Mus. Biol. Mello Leitão (N. Sér.) 2014, 36, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzi, H. Árvores Brasileiras: Manual de Identificação e Cultivo de Plantas Arbóreas do Brasil; Instituto Plantarum: Nova Odessa, Brazil, 2020; 384p. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, M.E.V.; Silva, D.C.G.; Macedo, E.S.; Souza, M.A. Potencial antioxidante e alelopático de Crataeva tapia L. Divers J. 2019, 4, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Walcott, B.; Zhou, D.; Gustchina, A.; Lasanajak, Y.; Smith, D.F.; Ferreira, R.S.; Correia, M.T.S.; Paiva, P.M.G.; Bovin, N.V.; et al. Structural studies of the interaction of Crataeva tapia bark protein with heparin and other glycosaminoglycans. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 2148–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonhardt, C.; Bueno, O.L.; Calil, A.C.; Busnello, C.P. Morfologia e desenvolvimento de plântulas de 29 espécies arbóreas nativas da área da bacia hidrográfica do Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Iheringia Sér. Bot. 2008, 63, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, G.R.C.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Miranda, S.C. Dados biométricos de frutos e sementes de Hymenaea courbaril var stilbocarpa (Hayne) YT Lee & Langenh e H. martiana Hayne. Biotemas 2012, 25, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.A.; Ferreira, S.A.N. Fruit and seed biometry and seedling morphology of Parkia discolor (Spruce ex Benth.). Rev. Árvore 2017, 41, e410206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, S.H.; Torres, S.B.; Benedito, C.P. Biometria de frutos e sementes e germinação de melão-de-são-caetano. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2013, 15, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.M.; Cardoso, A.D.; Dutra, F.V.; Morais, O.M. Aspectos biométricos de frutos e sementes de Caesalpinia ferrea Mart. ex Tul. provenientes do semiárido baiano. Rev. Agric. Neotrop. 2017, 4, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, F.; Lima, L.B.; Luz, P.B. Caracterização morfológica do ramo, sementes e plântulas de Matayba guianensis Aubl. e produção de mudas em diferentes recipientes e substratos. Rev. Árvore 2014, 38, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.S.; Feitoza, G.V.; Flores, A.S. Taxonomic relevance of seed and seedling morphology in two Amazonian species of Entada (Leguminosae). Acta Amaz. 2014, 44, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavasi, U.C.; Malavasi, M.M. Influência do tamanho e do peso da semente na germinação e no estabelecimento de espécies de diferentes estágios da sucessão vegetal. Floresta Ambiente 2001, 8, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, M.C.; Scalon, S.P.Q.; Sari, A.P.; Scalon Filho, H.; Rosa, Y.B.C.J. Biometria de frutos e sementes e germinação de Magonia pubescens St. Hil. (Sapindaceae). Rev. Bras. Sementes 2009, 31, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, J.P.; Linhares, P.C.F.; Lima, G.K.L.; Pereira, M.F.S. Análise biométrica de sementes de feijão bravo (Capparis flexuosa) planta medicinal em Mossoró–RN. Agropec. Cient. Semi-Árido 2013, 9, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.F.; Abud, H.F.; Pinto, C.M.F.; Araujo, E.F.; Leal, C.A.M. Curva de embebição de sementes de pimentas biquinho e malagueta sob diferentes temperaturas. Rev. Bras. Agropec. Sustentável 2018, 8, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Moura, S.S.; Silva, R.S.; Alves, E.U.; Gonçalves, E.P.; Araújo, L.D.A.; Alves, M.M.; Araujo, P.C. Morphology of seeds, seedlings, and young plants of Dimorphandra gardneriana Tul. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár. 2019, 40, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompelli, M.F.; Jarma-Orozco, A.; Rodriguez-Páez, L.A. Imbibition and Germination of Seeds with Economic and Ecological Interest: Physical and Biochemical Factors Involved. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acchile, S.; Costa, R.N.; Silva, L.K.S.; Santos, J.C.C.; Silva, D.M.R.; Silva, J.V. Biometria de frutos e sementes e determinação da curva de absorção de água de sementes de Sesbania virgata (Cav.) Pers. Sci. Electron. Arch. 2017, 10, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, N.M.; Nakagawa, J. Sementes: Ciência, Tecnologia e Produção, 5th ed.; FUNEP: Jaboticabal, Brazil, 2012; 590p. [Google Scholar]

- Brancalion, P.H.S.; Novembre, A.D.L.C.; Rodrigues, R.R. Temperatura ótima de germinação de sementes de espécies arbóreas brasileiras. Rev. Bras. Sementes 2010, 32, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.K.M.; Carvalho, J.M.B.; Souza, J.S.; Souza, S.A. Germinação de sementes de Aspidosperma subincanum Mart. ex A. DC em diferentes temperaturas. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2015, 17, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Moura, S.S.; Alves, E.U.; Galindo, E.A.; Moura, M.F.; Melo, P.A.F.R. Qualidade fisiológica de sementes de Crataeva tapia L. submetidas a diferentes métodos de extração da mucilagem. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2014, 36, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Regras Para Análise de Sementes; Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento, Secretaria de Defesa Agropecuária, MAPA/ACS: Brasília, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glória, B.A. Morfologia Vegetal; Centro Acadêmico “Luiz de Queiroz”, Departamento Editorial: Piracicaba, Brazil, 1993; 107p. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, W.N.; Vidal, M.R.R. Botânica—Organografia: Quadros Sinóticos Ilustrados de Fanerógamos, 3rd ed.; UFV Impr. Univ.: Viçosa, Brazil, 1995; 114p. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, G.M. Frutos e Sementes: Morfologia Aplicada à Sistemática de Dicotiledôneas; Editora UFV: Viçosa, Brazil, 2004; 443p. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, K.S.; Guimarães, R.M.; Almeida, I.F.; Clemente, A.C.S. Alterações fisiológicas e bioquímicas durante a embebição de sementes de sucupira-preta (Bowdichia virgilioides Kunth.). Rev. Bras. Sementes 2009, 31, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros Neto, J.J.S. Sementes estudos tecnológicos. In Água na Semente: Importância Para a Tecnologia de Armazenagem, 1st ed.; Almeida, F.A.C., Queiroga, V.P., Melo, B.A., Eds.; IFS: Aracaju, Brazil, 2014; Cap. 3; pp. 55–84. Available online: www.ifs.edu.br/images/EDIFS/ebooks/2014/Sementes_Estudos_Tecnológicos.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Maguire, J.O. Speed of germination and in selection and evaluation for seedling emergence and vigor. Crop Sci. 1962, 2, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, E.G.; Lorenzi, H. Morfologia Vegetal: Organografia e Dicionário Ilustrado de Morfologia das Plantas Vasculares; Instituto Plantarum de Estudos da Flora: São Paulo, Brazil, 2007; 416p. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, D.F. Sisvar: A computer statistical analysis system. Ciênc. Agrotecnol. 2011, 35, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, M.B. Biometria de frutos e sementes e crescimento pós-seminal de Acca sellowiana (O. Berg. Burret) Myrtaceae. Cad. Pesqui. 2018, 30, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.G.; Vieira, F.A.; Fonseca-Junior, E.M. Biometria de frutos e endocarpos de murici (Byrsonima verbascifolia Rich. ex A. Juss.). Cerne 2006, 12, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Brandão, A.A.; Neve, J.M.G.; Silva, H.P.; Coutinho, P.H. Caracterização biométrica de frutos de macaúba em diferentes estádios de maturação, provenientes de duas regiões do Estado de Minas Gerais. Glob. Sci. Technol. 2014, 7, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel-Gomes, F. Curso de Estatística Experimental, 15th ed.; Fealq: Piracicaba, Brazil, 2009; 451p. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, A.V.R.; Freitas, T.A.S.; Souza, L.S.; Fonseca, M.D.S.; Souza, J.S. Morfologia de frutos e sementes e germinação de Poincianella pyramidalis (Tul.) L. P. Queiroz, comb. Nov. Ciênc. Florest. 2016, 26, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.C.; Silva, D.M.R.; Costa, R.N.; Santos, S.A.; Silva, L.K.S.; Silva, J.V. Biometria de frutos e sementes e tratamentos pré-germinativos em sementes de Hymenaea courbaril. Rev. Agronegócio Meio Ambiente 2019, 12, 957–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, E.E.S.; Novaes, C.R.D.B.; Silva, L.B.; Chaves, L.J. Structure of the phenotypic variability of fruit and seeds of Dipteryx alata Vogel (Fabaceae). Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2020, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehling, F.; Jaroszewicz, B.; Braasch, L.V.; Albrecht, J.; Jordano, P.; Schlautmann, J.; Farwig, N.; Schabo, D.G. Within-species trait variation can lead to Size Limitations in Seed dispersal of Small-fruited plants. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 698885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaes, C.R.D.B.; Mota, E.E.S.; Novaes, E.; Telles, M.P.C.; Chaves, L.J. Structure of the phonotypic variability of fruit and seed traits in natural populations of Eugenia dysenterica DC. (Myrtaceae). Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2018, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares Neto, R.L.; Jardim, J.G. Capparaceae no Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil. Rodriguésia 2015, 66, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.C.; Silva, D.M.R.; Costa, R.N.; Silva, C.H.; Santos, W.S.; Moura, F.B.P.; Silva, J.V. Aspectos biométricos e morfológicos de frutos e sementes de Schinopsis brasiliensis. Nativa 2018, 6, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.K.; Mendonça, M.S.; Gentil, D.F.O. Aspectos biométricos, morfoanatômicos e histoquímicos do pirênio de Bactris maraja (Arecaceae). Rodriguésia 2015, 66, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares Neto, R.L.; Thomas, W.W.; Barbosa, M.R.V.; Roalson, E.H. A Well-known “Mussambê” is a new species of Tarenaya (Cleomaceae) from South America. Syst. Bot. 2019, 44, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.D.; Ellis, R.H. A protocol to Determine Seed Storage Behaviour; International Plant Genetic Resources Institute: Rome, Italy, 1996; 64p. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley, J.D.; Black, M. Seeds: Physiology of Development and Germination; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; 445p. [Google Scholar]

- Holanda, A.E.R.; Medeiros-Filho, S.; Diogo, I.J.S. Influência da luz e da temperatura na germinação de sementes de sabiá (Mimosa caesalpiniifolia Benth.—Fabaceae). Gaia Sci. 2015, 9, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, S.; Onen, H.; Tad, S.; Ozaslan, C.; Mahmoud, S.F.; Brestic, M.; Zivcak, M.; Skalicky, M.; El-Shehawi, A.M. The influence of environmental factors on seed germination of Polygonum perfoliatum L.: Implications for management. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, V.G.P.; Vieira, J.P.U.S.; Schedenffeldta, B.F.; Hirata, A.C.S.; Monquero, P.A. Effect of temperature, light, seeding depth and mulch on germination of Commelina benghalensis and Richardia brasiliensis. Braz. J. Biol. 2024, 84, e281402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, E.A.; Alves, E.U.; Silva, K.B.; Barrozo, L.M.; Santos-Moura, S.S. Germinação e vigor de sementes de Crataeva tapia L. em diferentes temperaturas e regimes de luz. Rev. Ciênc. Agronômica 2012, 43, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner Júnior, A.; Franzon, R.C.; Silva, J.O.C.; Santos, C.E.M.; Gonçalves, R.S.; Bruckner, C.H. Efeito da temperatura na germinação de sementes de três espécies de jabuticabeira. Rev. Ceres 2007, 54, 345–350. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, A.C.B.; Borges, E.E.L.; Silva, L.J. Fisiologia da germinação de sementes de Dalbergia nigra (Vell.) Allemão ex Benth. sob diferentes temperaturas e tempos de exposição. Rev. Árvore 2015, 39, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonamigo, T.; Scalon, S.P.Q.; Nunes, D.P.; Pereira, Z.V. Biometria de frutos e germinação de sementes de Tocoyena formosa (Cham. & Schltdl.) K. Schum. Agrarian 2019, 12, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.R.; Almeida, M.C.; Wittmann, F. Biometria e germinação de sementes de Macrolobium acaciifolium (Benth.) Benth. de várzea e igapó da Amazônia Central. Iheringia Sér. Bot. 2020, 75, e2020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgel, J.T.A.; Sobrinho, S. Poliembrionia em mirtáceas frutíferas. Bragantia 1951, 11, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L. Cotyledon anatomy in the Leguminosae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1983, 86, 325–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, I.R.; Souza, V.Q.; Nardino, M.; Follmann, D. Associações fenotípicas entre caracteres fisiológicos da soja contrastante ao hábito de crescimento. Glob. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassif, S.P.; Cicero, S.M. Avaliação de sementes de acerola por meio de raios-X. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2006, 28, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, C.H.Q.; Cicero, S.M.; Silva, F.F.; Gomes Junior, F.G. Morphology and germination of Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. seeds. J. Seed Sci. 2023, 45, e202345011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.H.G.; Iwazaki, M.C.; Oliveira, D.M.T. Morfologia das plântulas, anatomia dos cotilédones e eófilos de três espécies de Mimosa (Fabaceae, Mimosoideae). Rodriguesia 2014, 65, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, R.A.; Duarte, V.C.B.; Bevilaqua, A.P.; Antunes, I.F. Efeito de preparados homeopáticos no vigor de sementes e desenvolvimento de plântulas de feijão. Rev. Ciênc. Agrárias 2019, 42, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuaden, E.R.; Albuquerque, M.C.F.; Coelho, M.F.B.; Mendonça, E.A.F. Germinação e morfologia de sementes e de plântulas de hortelã-do-campo Hyptis cana Pohl. (Lamiaceae). Rev. Bras. Sementes 2005, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistical Parameters | Length (cm) | Width (cm) | Mass (g) | NumS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 4.33 | 4.37 | 51.47 | 19.12 |

| Standard deviation | 0.46 | 0.43 | 14.64 | 6.91 |

| Maximum | 5.33 | 5.42 | 97.59 | 40.00 |

| Minimum | 3.25 | 3.34 | 26.69 | 7.00 |

| Skewness (1) | −0.11 | −0.11 | 0.63 | 0.72 |

| Kurtosis +3 (2) | 2.54 | 2.66 | 3.30 | 3.11 |

| Shapiro–Wilk (3) | 0.63 ns | 0.62 ns | 0.01 * | 0.00 ** |

| CV (%) | 10.71 | 9.83 | 28.44 | 36.15 |

| Statistical Parameters | Length (cm) | Width (cm) | Thick (cm) | Mass (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.49 | 0.15 |

| Standard deviation | 0.09 | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Maximum | 1.08 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.23 |

| Minimum | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.09 |

| Skewness (1) | 0.40 | −0.47 | 0.93 | 0.23 |

| Kurtosis +3 (2) | 2.77 | 3.62 | 4.76 | 3.96 |

| Shapiro–Wilk (3) | 0.08 ns | 0.02 * | 0.00 ** | 0.31 ns |

| CV (%) | 10.20 | 9.38 | 17.19 | 14.10 |

| SV | DF | Mean Squares | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G (%) | GFC (%) | GSI | RL (cm) | SL (cm) | RDM (g) | SDM (g) | HS (%) | AbS (%) | ||

| Temp. | 2 | 508.0833 ** | 306.583 ** | 0.44066 ** | 0.00352 ** | 0.00905 ** | 0.00001 ** | 0.00004 ** | 14.33333 ns | 1.75000 ns |

| Residue | 9 | 6.61111 | 3.75000 | 0.00579 | 0.00037 | 0.00092 | 5.30555 | 0.00001 | 7.88889 | 3.19444 |

| Total | 11 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CV (%) | – | 9.95 | 19.53 | 9.13 | 18.31 | 11.61 | 9.18 | 14.60 | 23.09 | 54.99 |

| Temp. (°C) | G (%) | GFC (%) | GSI | RL (cm) | SL (cm) | RDM (g) | SDM (g) | HS (%) | AbS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 30 c | 1 c | 0.49 c | 0.011 b | 0.022 b | 0.001 b | 0.004 b | 14 a | 4 a |

| 30 | 50 a | 10 b | 1.15 a | 0.013 a | 0.031 a | 0.004 a | 0.010 a | 10 a | 3 a |

| 35 | 34 b | 19 a | 0.85 b | 0.007 c | 0.025 b | 0.001 b | 0.005 b | 13 a | 4 a |

| CV (%) | 9.95 | 19.53 | 9.13 | 18.31 | 11.61 | 9.18 | 14.60 | 23.09 | 54.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, R.d.S.; Cruz, F.R.d.S.; Silva, M.L.M.d.; Nascimento, M.d.G.R.d.; Sousa, E.M.d.; Cordeiro, J.M.P.; Silva, J.H.C.S.; Alves, E.U. From Seed to Young Plant: A Study on Germination and Morphological Characteristics of Crateva tapia L. (Capparaceae). Biology 2025, 14, 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121729

Silva RdS, Cruz FRdS, Silva MLMd, Nascimento MdGRd, Sousa EMd, Cordeiro JMP, Silva JHCS, Alves EU. From Seed to Young Plant: A Study on Germination and Morphological Characteristics of Crateva tapia L. (Capparaceae). Biology. 2025; 14(12):1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121729

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Rosemere dos Santos, Flávio Ricardo da Silva Cruz, Maria Lúcia Maurício da Silva, Maria das Graças Rodrigues do Nascimento, Edlânia Maria de Sousa, Joel Maciel Pereira Cordeiro, João Henrique Constantino Sales Silva, and Edna Ursulino Alves. 2025. "From Seed to Young Plant: A Study on Germination and Morphological Characteristics of Crateva tapia L. (Capparaceae)" Biology 14, no. 12: 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121729

APA StyleSilva, R. d. S., Cruz, F. R. d. S., Silva, M. L. M. d., Nascimento, M. d. G. R. d., Sousa, E. M. d., Cordeiro, J. M. P., Silva, J. H. C. S., & Alves, E. U. (2025). From Seed to Young Plant: A Study on Germination and Morphological Characteristics of Crateva tapia L. (Capparaceae). Biology, 14(12), 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121729