Brain Gamma-Stimulation: Mechanisms and Optimization of Impact

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

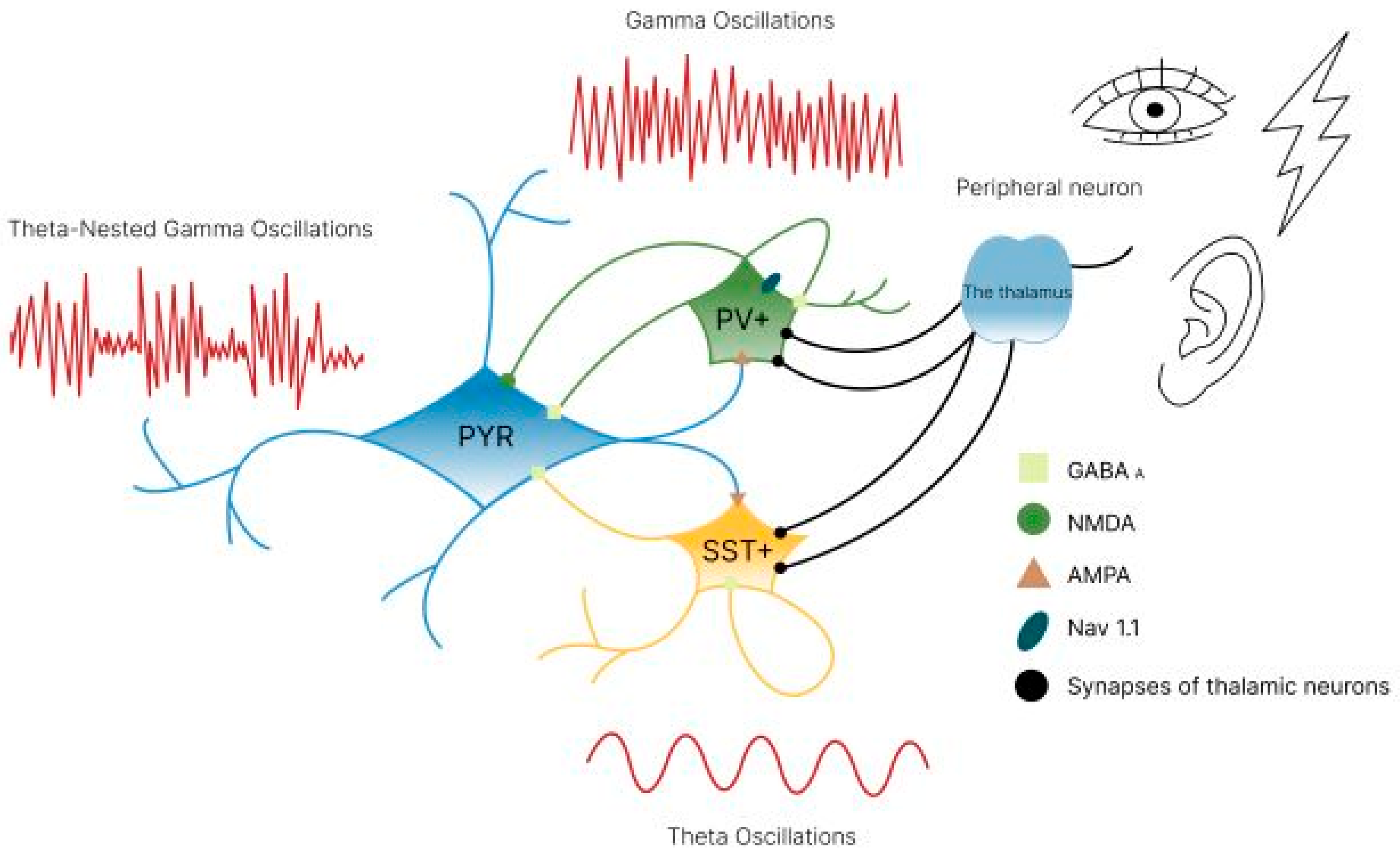

2. General Functions of γ-Rhythms, Mechanism of Regulations

3. Literature Data Analysis Protocol

3.1. Criteria for Including Publications in the Analysis

3.2. Data Processing

4. Dependence of the Effectiveness of γ-Stimulation on the Characteristics of the Stimulus and Responding Systems

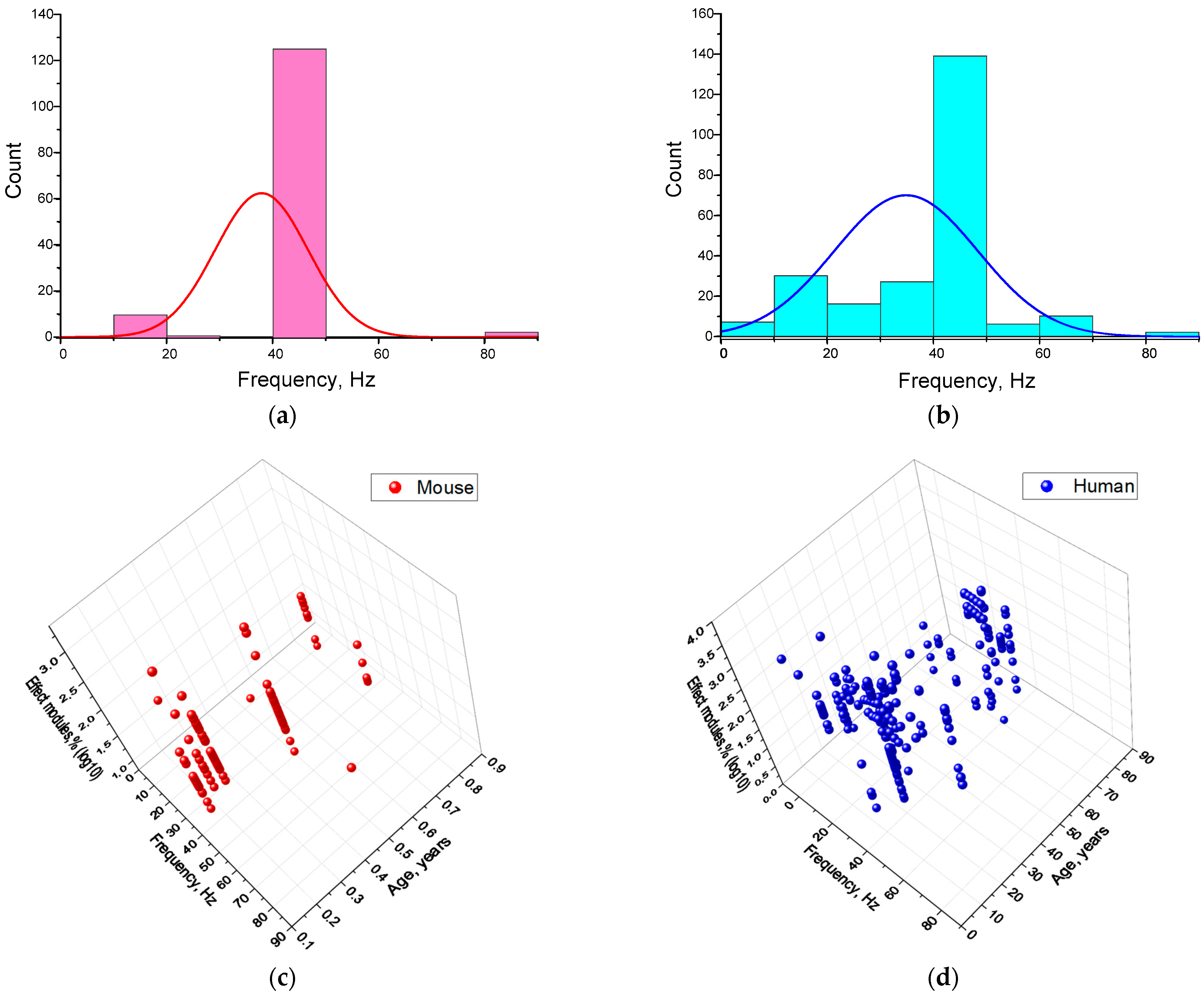

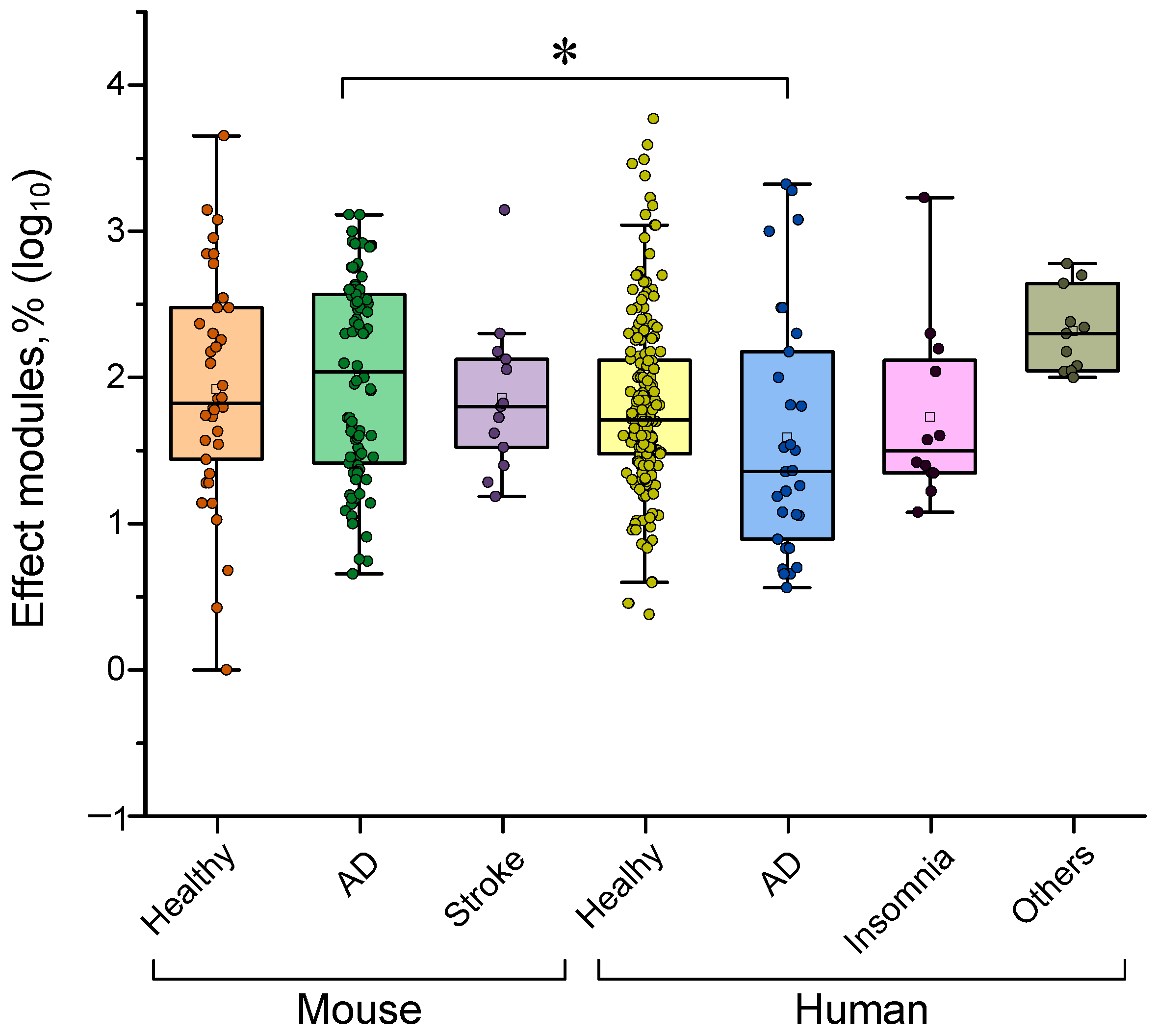

4.1. Dependence of the Effectiveness of γ-Stimulation on Species

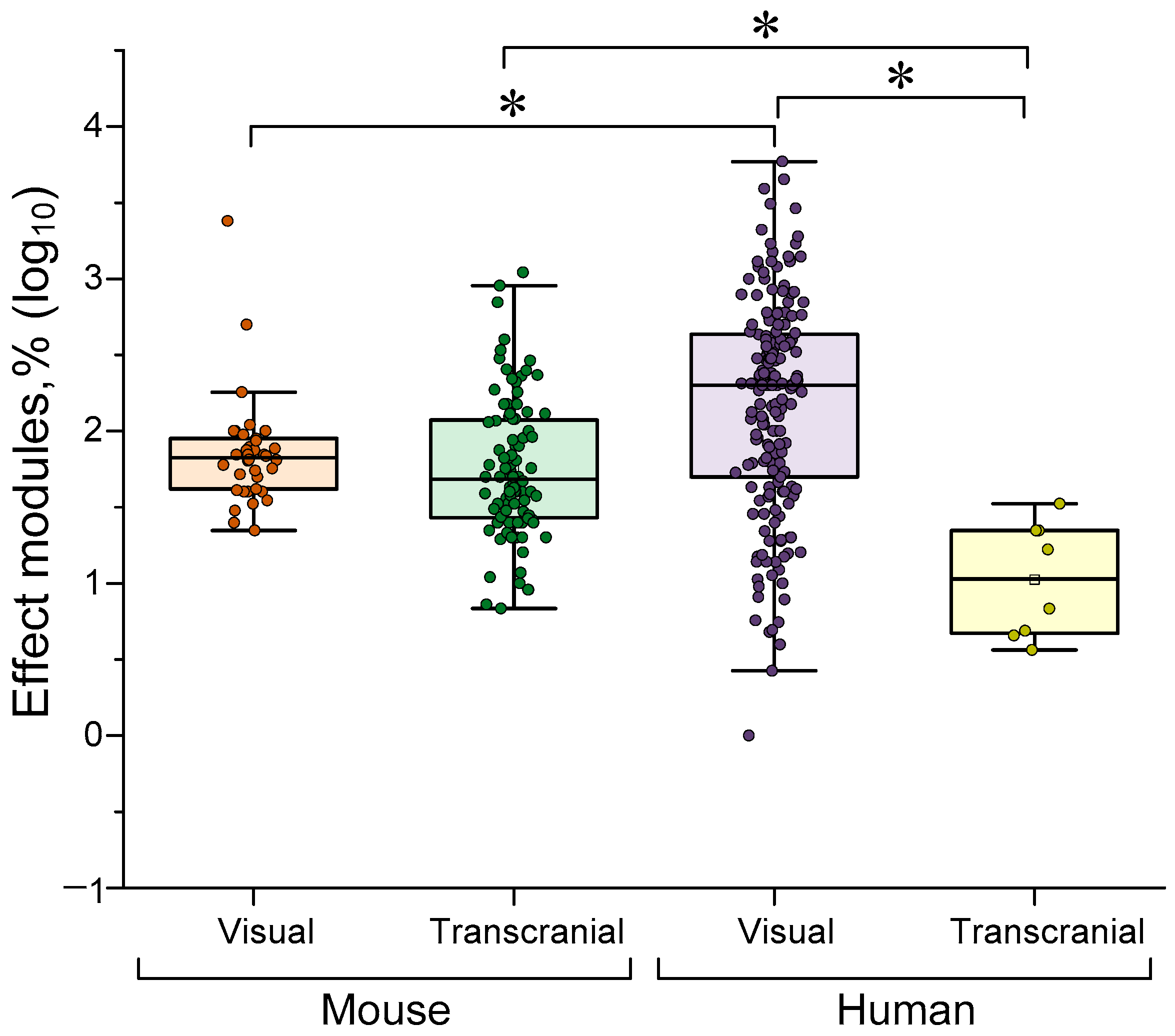

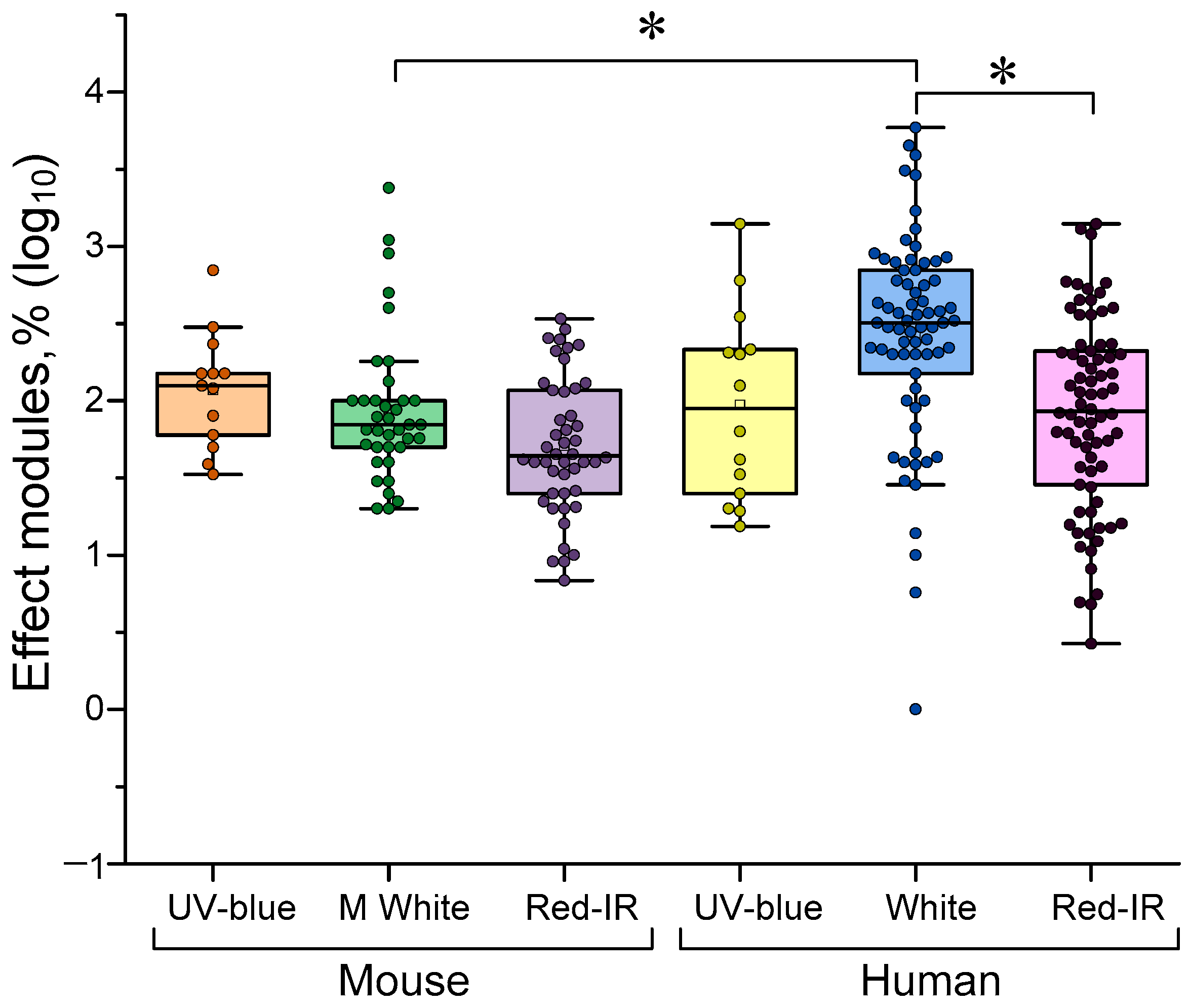

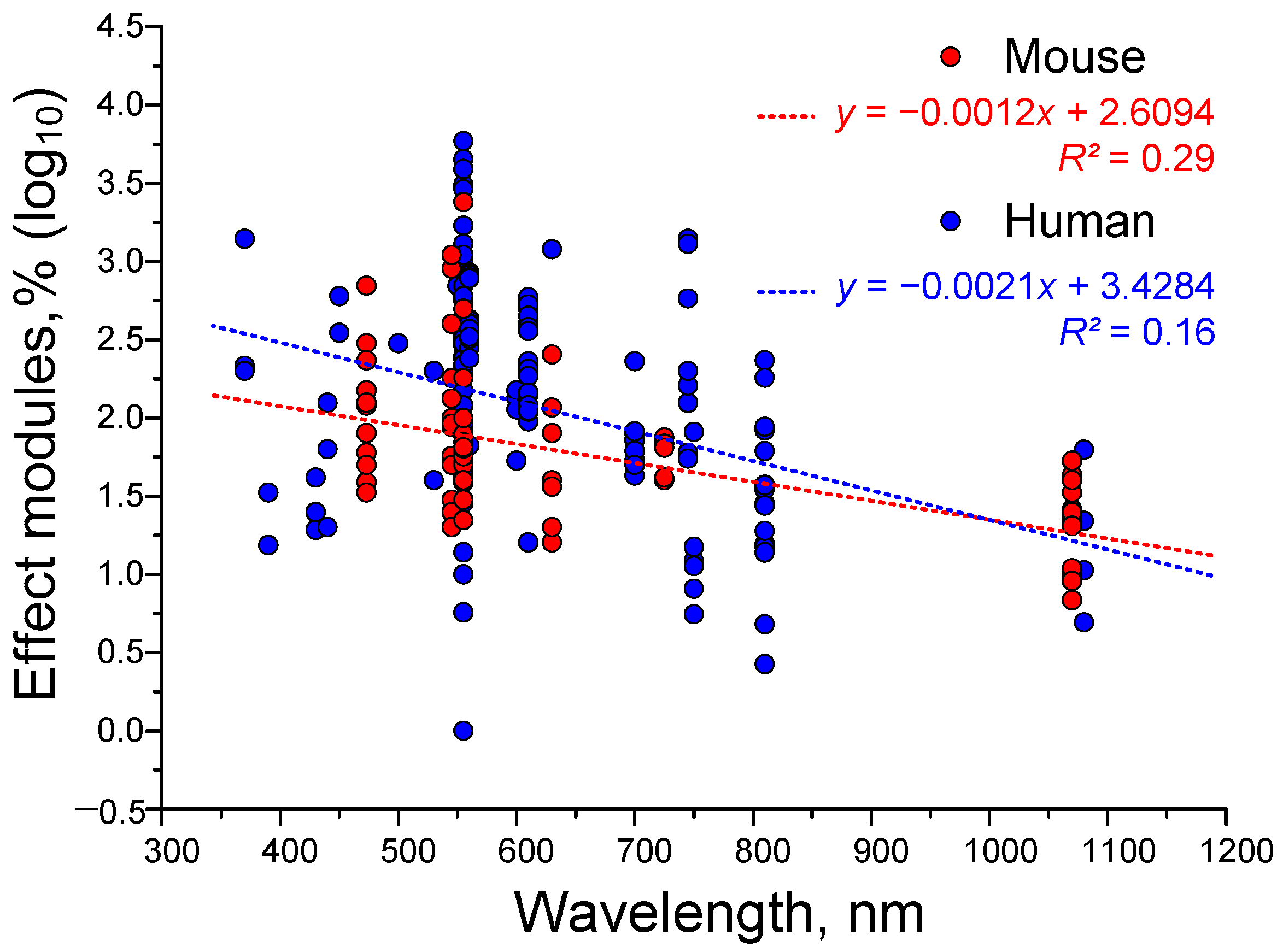

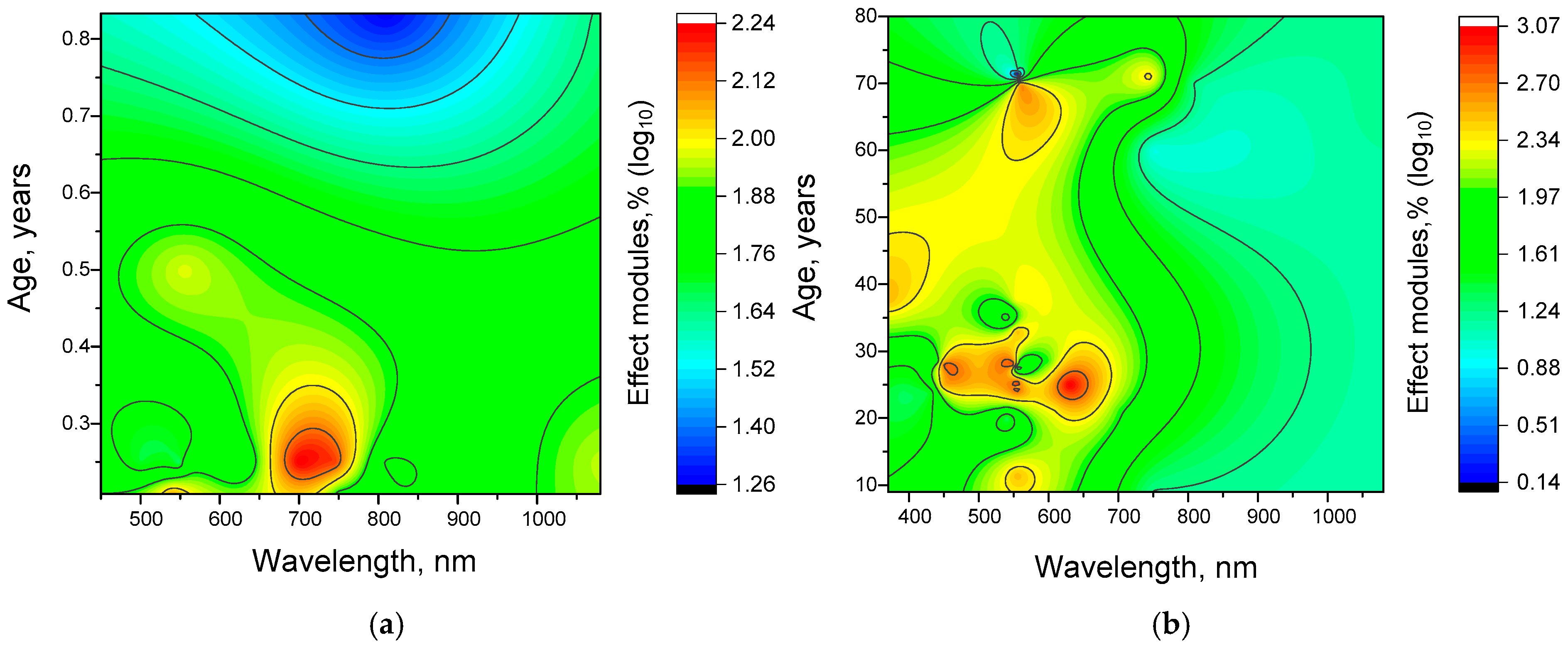

4.2. Dependence of the Efficiency of γ-Stimulation on the Type of Stimulus

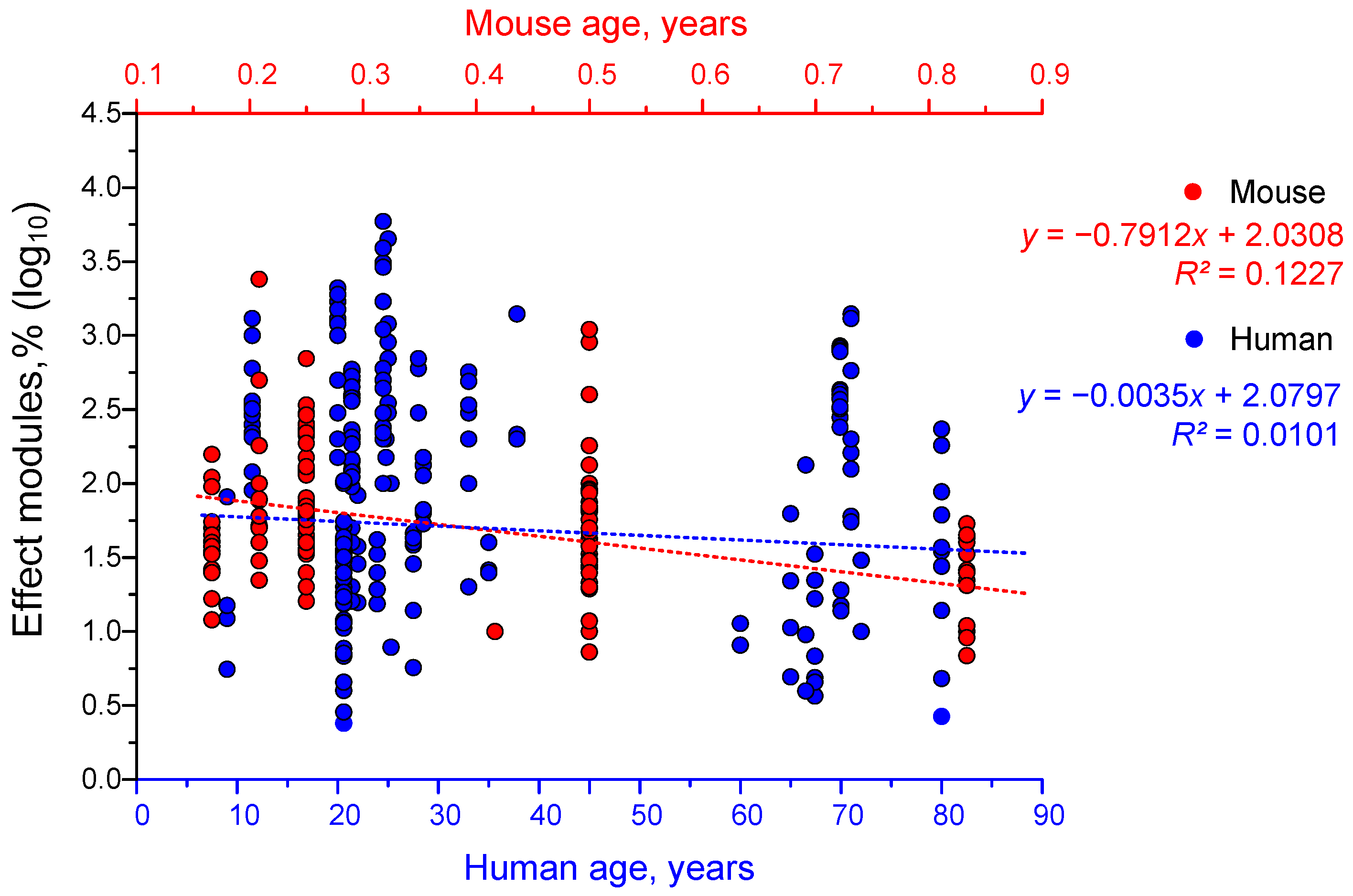

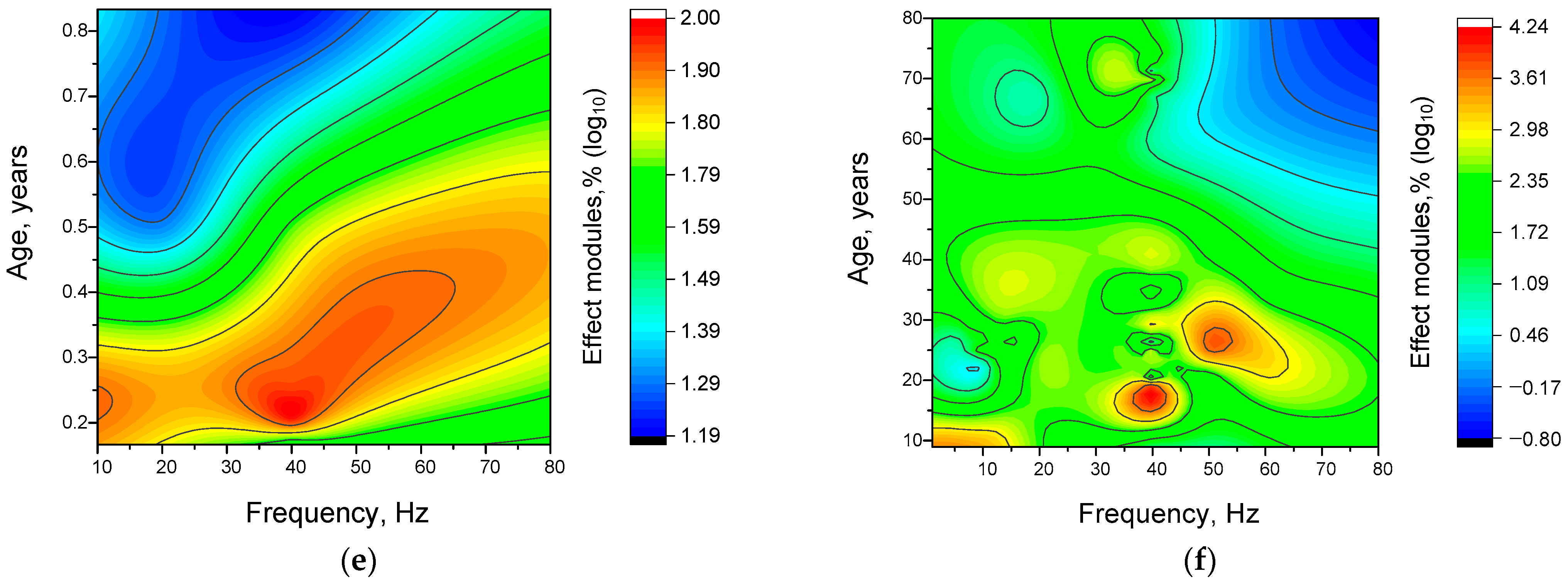

4.3. Dependence of the Effectiveness of γ-Stimulation on Age

4.4. Dependence of the Efficiency of γ-Stimulation on the Frequency of Stimulating Action

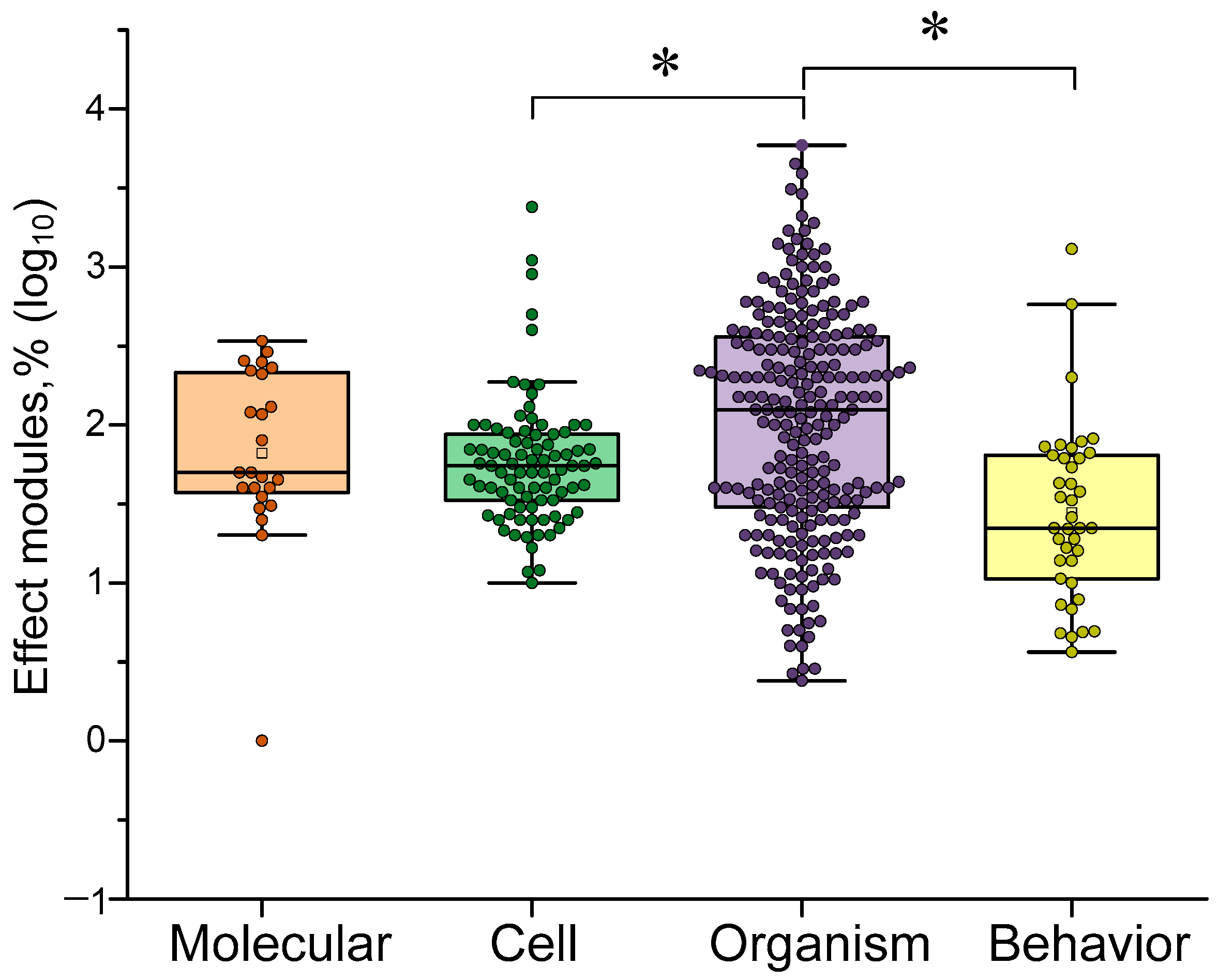

4.5. Dependence of the Efficiency of γ-Stimulation on the Target

4.6. Dependence of the Effectiveness of γ-Stimulation on Pathology

5. Mechanisms of γ-Stimulation Action

5.1. Visual Stimulation

5.2. Modulation of GABAergic Interneuron Activity

5.3. Acetylcholine Mechanism of γ-Oscillation Activation

5.4. Modulation of Neural Network Activity

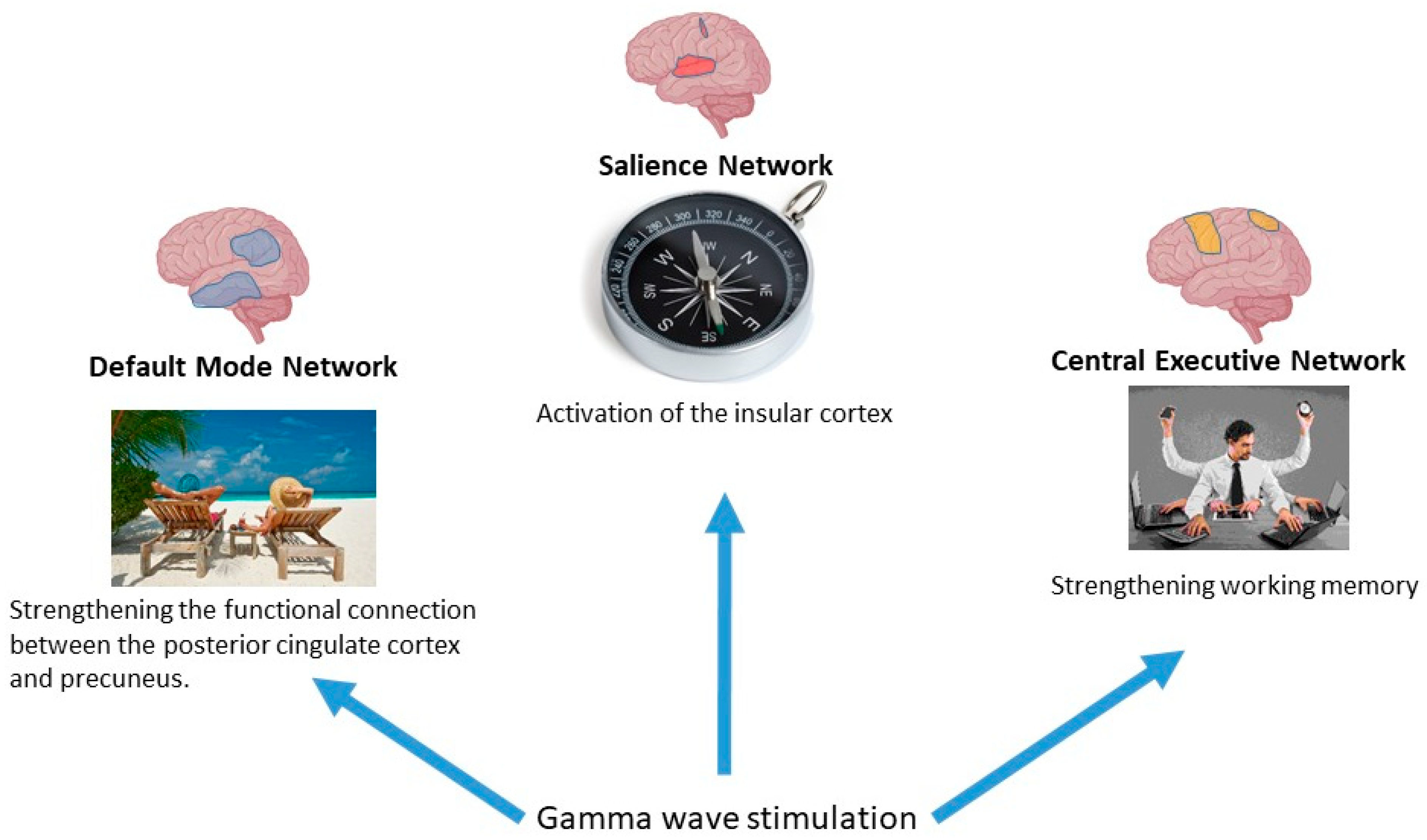

5.4.1. Basic Modes of Brain Function and γ-Stimulation

5.4.2. The Default Mode Network

Functions of the DMN

Effects of γ-Stimulation on the Functioning of the DMN

5.4.3. Central Executive Network

Central Executive Network Functions

- Concentration and attention: maintaining focus on the task.

- Working memory involves retaining and manipulating information in the mind.

- Planning and control involves developing a strategy of actions and controlling their implementation.

- Inhibiting impulses and preventing rash actions.

Effects of γ-Stimulation on Central Executive Network

5.4.4. Salience Network Executive Network

Salience Network Functions

Effects of γ-Stimulation on the Salience Network

5.5. Activation of Neurogenesis

5.6. Adenosine Hypothesis

5.7. Effect of γ-Stimulation on Microglia and Inflammation

6. Optimization of γ-Stimulation

6.1. Visual γ-Stimulation in Young Adults

6.2. Visual γ-Stimulation in Older Adults

6.3. The Problem of Stroboscopic Flicker and Its Solution

6.4. Increasing the Exposure Time by Stimulation During Sleep

6.5. Cognitive Task During Stimulation

6.6. Motor (Behavioral) Activity During Stimulation

6.7. Sound Wave Characteristics During Auditory Stimulation

6.8. The Influence of Glucose Metabolism on the γ-Rhythm

7. Clinical Trials

8. Limitations and Prospects

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| ACh | Acetylcholine |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF1 | Colony-stimulating factor 1 |

| DMN | default mode network |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| GENUS | Gamma ENtrainment Using Sensory stimuli |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ING | Purely inhibitory populations of neurons |

| iNOS | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IR | Infrared |

| ISF | Invisible spectral flicker |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LED | Light-emitting diode |

| mAChRs | Muscarinic ACh receptors |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| M-CSF | Macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| MIP-1β | Macrophage inflammatory protein-1β |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B |

| NMDA | N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid |

| PING | Excitatory–inhibitory networks of neurons |

| PKR | Protein kinase R |

| PLX3397 | Inhibitor of the colony-stimulating factor 1 |

| PV | Parvalbumin |

| SST | Somatostatin |

| SVEP | Steady-state visual evoked potentials |

| TLR | Toll-like receptors |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VIP | vasoactive intestinal peptide |

| Ym1 | Heparin-binding lectin |

Appendix A

| # | Organism | Age, Years | Pathology | Type of Impact | Type of Exhibition | Duration, s | Additional Conditions | Additional Conditions Characteristics | Analyzed Parameter | Effect Module % | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Human | 35 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 120 | Eyes | Open | Central–frontal region eeg 25–50 hz oscillations | 25 | [304] |

| Human | 35 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 120 | Eyes | Closed | Central–frontal region eeg 25–50 hz oscillations | 40 | ||

| Human | 35 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 120 | Eyes | Open | Central–frontal region eeg 25–50 hz oscillations | 26 | ||

| Human | 35 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 120 | Eyes | Closed | Central–frontal region eeg 25–50 hz oscillations | 25 | ||

| 2 | Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 120 | Eyes | Open | Alpha rhythm | 53 | [303] |

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 120 | Eyes | Closed | Alpha rhythm | 29 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 1920 | Eyes | Open | Alpha rhythm | 24 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 1920 | Eyes | Closed | Alpha rhythm | 53 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 120 | Eyes | Open | Deplta rhythm | 23 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 120 | Eyes | Closed | Deplta rhythm | 5 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 1920 | Eyes | Open | Deplta rhythm | 32 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 1920 | Eyes | Closed | Deplta rhythm | 14 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 120 | Eyes | Open | Theta rhythm | 22 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 120 | Eyes | Closed | Theta rhythm | 11 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 1920 | Eyes | Open | Theta rhythm | 33 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Audio | Binaural | 1920 | Eyes | Closed | Theta rhythm | 22 | ||

| 3 | Human | 9 | Insomnia | Light | Visually | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 750 | Sol duration | 81 | [299] |

| Human | 9 | Insomnia | Light | Visually | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 750 | Tst duration | 12 | ||

| Human | 9 | Insomnia | Light | Visually | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 750 | Se duration | 15 | ||

| Human | 9 | Insomnia | Light | Visually | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 750 | Rem amount | 6 | ||

| 4 | Human | 60 | BA | Light | Visually | “-” | Wavelength, nm | 750 | N-back test accuracy | 11 | [293] |

| Human | 60 | BA | Light | Visually | “-” | Wavelength, nm | 750 | Reaction time in a 1-back test | 8 | ||

| 5 | Human | 22 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 350 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Score of the computerized visual memory test | 29 | [273] |

| Human | 22 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 350 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Longest correct span of the computerized visual memory test | 16 | ||

| Human | 22 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 350 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Oxi-hb changedduring early phase of test | 83 | ||

| Human | 22 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 350 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Oxi-hb changedduring late phase of test | 38 | ||

| 6 | Human | 70 | BA | Light | Visually | 126,000 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Mini-mental state exam results | 15 | [312] |

| Human | 70 | BA | Light | Visually | 126,000 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale-cognitive subscale scores | 19 | ||

| Human | 70 | BA | Light | Visually | 63,000 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Mini-mental state exam results | 14 | ||

| Human | 70 | BA | Light | Visually | 63,000 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale-cognitive subscale scores | 19 | ||

| 7 | Human | 80 | BA | Light | Visually | 21,600 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale-cognitive scores | 5 | [313] |

| Human | 80 | BA | Light | Visually | 21,600 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale-cognitive scores | 14 | ||

| Human | 80 | BA | Light | Visually | 21,600 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Neuropsychiatric inventory scopes | 35 | ||

| Human | 80 | BA | Light | Visually | 21,600 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Neuropsychiatric inventory scopes | 61 | ||

| Human | 80 | BA | Light | Visually | 21,600 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Total perfusion | 37 | ||

| Human | 80 | BA | Light | Visually | 21,600 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Superior frontal perfusion | 3 | ||

| Human | 80 | BA | Light | Visually | 21,600 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Superior parietal perfusion | 88 | ||

| Human | 80 | BA | Light | Visually | 21,600 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Supramarginal perfusion | 28 | ||

| Human | 80 | BA | Light | Visually | 21,600 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Connectivy between posterior cingulate cortex and left lateral parietal | 233 | ||

| Human | 80 | BA | Light | Visually | 21,600 | Wavelength, nm | 810 | Connectivy between posterior cingulate cortex and right lateral parietal | 181 | ||

| 8 | Human | 65 | Parkinson’s disease | Light | Visually | 8568 | Wavelength, nm | 1080 | Trail making a | 63 | [313] |

| Human | 65 | Parkinson’s disease | Light | Visually | 8568 | Wavelength, nm | 1080 | Adas- cog ideational praxis | 22 | ||

| Human | 65 | Parkinson’s disease | Light | Visually | 8568 | Wavelength, nm | 1080 | Adas- cog boston naming | 11 | ||

| Human | 65 | Parkinson’s disease | Light | Visually | 8568 | Wavelength, nm | 1080 | Cortical perfusion | 5 | ||

| 9 | Human | 76 | Dementia | Light | Visually | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 700 | Emotional state | 71 | [284] |

| Human | 76 | Dementia | Light | Visually | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 700 | Psychiatric symptom | 43 | ||

| Human | 76 | Dementia | Light | Visually | 144,000 | Wavelength, nm | 700 | Psychiatric symptom | 79 | ||

| Human | 76 | Dementia | Light | Visually | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 700 | Sleep disturbances | 73 | ||

| Human | 76 | Dementia | Light | Visually | 144,000 | Wavelength, nm | 700 | Sleep disturbances | 82 | ||

| Human | 76 | Dementia | Light | Visually | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 700 | Orientation | 54 | ||

| Human | 76 | Dementia | Light | Visually | 144,000 | Wavelength, nm | 700 | Orientation | 62 | ||

| 10 | Human | 25 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 1800 | Maximum wavelength, nm | 630 | Gamma-rhythm power | 1200 | [282] |

| Human | 25 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 1800 | Maximum wavelength, nm | 450 | Gamma-rhythm power | 350 | ||

| 11 | Human | 28 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 300 | Wavelength, nm | 500 | Gamma-rhythm power | 300 | [281] |

| Human | 28 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 300 | Wavelength, nm | 450 | Gamma-rhythm power | 600 | ||

| Human | 28 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 300 | Wavelength, nm | 550 | Gamma-rhythm power | 700 | ||

| 12 | Human | 24.8 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Alpha rhythm power | 200 | [272] |

| Human | 24.8 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Alpha rhythm power | 150 | ||

| 13 | Human | 71.5 | BA | Light | Visually | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Amyloid-β (a β) content | 1 | [270] |

| 14 | Human | 25 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 300 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power without cognitive task | 900 | [123] |

| Human | 25 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 300 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power with cognitive task | 700 | ||

| Human | 25 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 300 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Different in p300 amplitude | 300 | ||

| Human | 25 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 300 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Different in p300 latency | 4500 | ||

| 15 | Human | 71 | BA | Lighting and audio | Combination | 16,470 | Wavelength, nm | 745 | Gamma-rhythm power | 1400 | [192] |

| Human | 71 | BA | Lighting and audio | Combination | 16,470 | Wavelength, nm | 745 | Ventricular volume change | 60 | ||

| Human | 71 | BA | Lighting and audio | Combination | 16,470 | Wavelength, nm | 745 | Hippocampal atrophy | 55 | ||

| Human | 71 | BA | Lighting and audio | Combination | 16,470 | Wavelength, nm | 745 | Pcc connectivity | 125 | ||

| Human | 71 | BA | Lighting and audio | Combination | 16,470 | Wavelength, nm | 745 | Mediam visual network connectivity | 161 | ||

| Human | 71 | BA | Lighting and audio | Combination | 16,470 | Wavelength, nm | 745 | Interdaily sleep stability | 200 | ||

| Human | 71 | BA | Lighting and audio | Combination | 16,470 | Wavelength, nm | 745 | Wake after sleep onset | 1300 | ||

| Human | 71 | BA | Lighting and audio | Combination | 16,470 | Wavelength, nm | 745 | Accuracy | 580 | ||

| 16 | Human | 72 | BA | Lighting and audio | Combination | 201,600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Pcc-pcu functional connectivity | 30 | [191] |

| Human | 72 | BA | Lighting and audio | Combination | 201,600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Tweak immune factor expression | 10 | ||

| 17 | Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power | 1300 | [138] |

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power | 1000 | ||

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power | 600 | ||

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power change in k29 | 250 | ||

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power change in k29 | 220 | ||

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power change in k29 | 120 | ||

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power change in k18 | 330 | ||

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power change in k18 | 290 | ||

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power change in k18 | 90 | ||

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power change in k19 | 360 | ||

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power change in k19 | 320 | ||

| Human | 11.5 | Healthy | Image rotation | Visually | 2100 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power change in k19 | 205 | ||

| 18 | Human | 27.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power by fmri | 14 | [314] |

| Human | 27.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power by fmri | 38 | ||

| Human | 27.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power by fmri | 43 | ||

| Human | 27.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power by fmri | 46 | ||

| Human | 27.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 29 | ||

| Human | 27.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 6 | ||

| Human | 27.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 40 | ||

| Human | 27.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 43 | ||

| 19 | Human | 33 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg in v1 | 100 | [117] |

| Human | 33 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg in v1 lfp | 560 | ||

| Human | 33 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Meg in v1 lfp signle spike density | 567 | ||

| Human | 33 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 20 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 20 | ||

| Human | 33 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 36 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 200 | ||

| Human | 33 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 48 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 300 | ||

| Human | 33 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 66 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 340 | ||

| Human | 33 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 96 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 490 | ||

| 20 | Human | 37.8 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 420 | Wavelength, nm | 370 | Theta rhythm power | 205 | [104] |

| Human | 37.8 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 420 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Theta rhythm power | 215 | ||

| Human | 37.8 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 420 | Wavelength, nm | 370 | Visually evoked potential | 215 | ||

| Human | 37.8 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 420 | Wavelength, nm | 370 | Alpha-gamma coupling f5 | 1400 | ||

| Human | 37.8 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 420 | Wavelength, nm | 370 | Alpha-gamma coupling c4 | 200 | ||

| 21 | Human | 23.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 5 | Wavelength, nm | 390 | Mean ssvep power | 15 | [103] |

| Human | 23.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 5 | Wavelength, nm | 430 | Mean ssvep power | 19 | ||

| Human | 23.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 5 | Wavelength, nm | 390 | Mean msi power | 33 | ||

| Human | 23.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 5 | Wavelength, nm | 430 | Mean msi power | 42 | ||

| Human | 23.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 5 | Wavelength, nm | 430 | Mean of cca coeddicient | 25 | ||

| 22 | Human | 28.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 15 | Wavelength, nm | 440 | Maximum gamma rhythm peaks values | 63 | [99] |

| Human | 28.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 15 | Wavelength, nm | 600 | Maximum gamma rhythm peaks values | 53 | ||

| Human | 28.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 15 | Wavelength, nm | 600 | Maximum gamma rhythm peaks values | 133 | ||

| Human | 28.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 15 | Wavelength, nm | 600 | Maximum gamma rhythm peaks values | 150 | ||

| Human | 28.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 15 | Wavelength, nm | 600 | Maximum gamma rhythm peaks values | 113 | ||

| Human | 28.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 15 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Maximum gamma rhythm peaks values | 67 | ||

| 23 | Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 800 | [72] |

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 850 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 830 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 820 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 790 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 780 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 430 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 420 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 400 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 380 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 370 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Strength of connectivity | 280 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Strength of connectivity | 320 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Strength of connectivity | 400 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Strength of connectivity | 370 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Strength of connectivity | 330 | ||

| Human | 69.9 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 560 | Strength of connectivity | 240 | ||

| 24 | Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 700 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 230 | [96] |

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 530 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 200 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 440 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 125 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 95 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 700 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 50 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 530 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 40 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 440 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 20 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 16 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 400 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 570 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 590 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 140 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 210 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 230 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 400 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 450 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 500 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 530 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 450 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 380 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 360 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in pz region | 360 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 200 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 190 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 205 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 185 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 145 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 120 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 110 | ||

| Human | 21.4 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 695 | Wavelength, nm | 610 | Event-related synchronization in fz region | 111 | ||

| 25 | Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Eyes | Open | Gamma-rhythm power | 150 | [95] |

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Eyes | Closed | Gamma-rhythm power | 150 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Eyes | Closed | Alhpa-rhythm power | 300 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Eyes | Open | Number of electrodes regisctrared gamma-rhythm enhacne | 1300 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Eyes | Open | Number of electrodes regisctrared gamma-rhythm enhacne | 1700 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Eyes | Open | Number of electrodes regisctrared gamma-rhythm enhacne | 500 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Eyes | Open | Number of electrodes regisctrared gamma-rhythm enhacne | 1500 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Eyes | Open | Number of electrodes regisctrared gamma-rhythm enhacne | 300 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Eyes | Open | Number of electrodes regisctrared gamma-rhythm enhacne | 200 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 20 | Eyes | Open | Number of electrodes regisctrared gamma-rhythm enhacne | 2100 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Eyes | Open | Number of electrodes regisctrared gamma-rhythm enhacne | 1900 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 5 | Eyes | Open | Number of electrodes regisctrared gamma-rhythm enhacne | 1200 | ||

| Human | 20 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 2 | Eyes | Open | Number of electrodes regisctrared gamma-rhythm enhacne | 1000 | ||

| 26 | Human | 25.3 | Healthy | Lighting and audio | Visually | 2 | Tactile stimuli | Eat | Test response time | 8 | [94] |

| Human | 25.3 | Healthy | Lighting and audio | Visually | 2 | Tactile stimuli | Eat | Imaginary gamma-rhythm cogerence | 100 | ||

| 27 | Human | 67.4 | Parkinson’s disease | Magnetic | Cranial | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Fingers velocity | 5 | [315] |

| Human | 67.4 | Parkinson’s disease | Magnetic | Cranial | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Fingers velocity | 4 | ||

| Human | 67.4 | Parkinson’s disease | Magnetic | Cranial | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Fingers move amplitude | 7 | ||

| Human | 67.4 | Parkinson’s disease | Magnetic | Cranial | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Fingers move amplitude | 5 | ||

| Human | 67.4 | Parkinson’s disease | Magnetic | Cranial | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Short-interval intracortical inhibition | 33 | ||

| Human | 67.4 | Parkinson’s disease | Magnetic | Cranial | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Short-interval intracortical inhibition | 17 | ||

| Human | 67.4 | Parkinson’s disease | Magnetic | Cranial | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Short-latency afferent inhibition | 22 | ||

| Human | 67.4 | Parkinson’s disease | Magnetic | Cranial | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Short-latency afferent inhibition | 22 | ||

| 28 | Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | First harmonic oscillation amplitude | 1700 | [54] |

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Second harmonic oscillation amplitude | 200 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | First harmonic oscillation amplitude | 600 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Second harmonic oscillation amplitude | 200 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | First harmonic oscillation amplitude | 500 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Second harmonic oscillation amplitude | 100 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | First harmonic oscillation amplitude | 240 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | First harmonic oscillation amplitude | 440 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | First harmonic oscillation amplitude | 220 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | First harmonic oscillation amplitude | 1100 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Other harmonics oscillation amplitude | 300 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | First harmonic oscillation amplitude | 3100 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Other harmonics oscillation amplitude | 5900 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Other harmonics oscillation amplitude | 3900 | ||

| Human | 24.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 30 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Other harmonics oscillation amplitude | 2900 | ||

| 29 | Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 300 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in f4 | 20 | [64] |

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 600 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in f4 | 12 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 900 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in f4 | 36 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in f4 | 18 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1500 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in f4 | 2 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in f4 | 4 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 300 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in fp2 | 32 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 600 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in fp2 | 11 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 900 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in fp2 | 23 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in fp2 | 18 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1500 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in fp2 | 5 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Gamma rhythm power in fp2 | 7 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 300 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in f4 | 15 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 600 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in f4 | 35 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 900 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in f4 | 23 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in f4 | 12 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1500 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in f4 | 15 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in f4 | 8 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 300 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in fp2 | 27 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 600 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in fp2 | 34 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 900 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in fp2 | 41 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in fp2 | 32 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1500 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in fp2 | 18 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Beta rhythm power in fp2 | 15 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 300 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in f4 | 42 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 600 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in f4 | 39 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 900 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in f4 | 39 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in f4 | 18 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1500 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in f4 | 11 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in f4 | 11 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 300 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in fp2 | 30 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 600 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in fp2 | 7 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 900 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in fp2 | 11 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1200 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in fp2 | 17 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1500 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in fp2 | 3 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Alpha rhythm power in fp2 | 3 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Word recall test result | 100 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Brunel mood scale worried | 51 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Brunel mood scale nervous | 44 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Brunel mood scale annoyed | 104 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Brunel mood scale miserable | 56 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Brunel mood scale sleepy | 25 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Brunel mood energy scale | 39 | ||

| Human | 20.6 | Healthy | Audio | Binourally | 1800 | “-” | “-” | Brunel mood scale muddled | 32 | ||

| 30 | Human | 66.5 | BA | Lighting and audio | Visually | 648,000 | “-” | “-” | Active periods during nighttime | 10 | [63] |

| Human | 66.5 | BA | Lighting and audio | Visually | 648,000 | “-” | “-” | Normalized active periods during nighttime | 4 | ||

| Human | 66.5 | BA | Lighting and audio | Visually | 648,000 | “-” | “-” | Activities of daily living | 133 | ||

| 31 | Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 2 | Escape latency | 7 | [316] |

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 3 | Escape latency | 38 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 4 | Escape latency | 42 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Escape latency | 64 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Step-through latency time | 67 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Time in probe quadrant | 75 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | P-act expression level | 50 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | P-gsk3beta expression level | 40 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | P-tay expression level | 30 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | App expression level | 47 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Number of abeta-positive cells | 57 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Number of gfap-positive astrocytes in ca | 19 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Number of gfap-positive astrocytes in dentate gyrus | 25 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Number of iba-1-positive astrocytes in ca | 25 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Number of iba-1-positive astrocytes in dentate gyrus | 33 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Tnfapha secretion | 28 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Il-6 secretion | 27 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Mitochondrial Ca2+ retention capacity | 70 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Mitochondrial ptp inhibition | 67 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Mitochondrial H2O2 generation | 12 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Bax protein expression level | 33 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Cyt c protein expression level | 27 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Caspase-3 protein expression level | 31 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Bcl-2 protein expression level | 25 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Tunel-positive cells number in dentate gyrus | 21 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Dcx-positive cells number in dentate gyrus | 38 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | BA | Light | Cranial | 216,000 | Training day | 5 | Neun/brdu-positive cells number in dentate gyrus | 90 | ||

| 32 | Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Intracellular adenosine concentration in v1 | 400 | [299] |

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Intracellular adenosine concentration in v2 | 900 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Intracellular adenosine concentration in v3 | 1100 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Caicium infux | 100 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Caicium infux | 180 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Local field potential oscillations | 20 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 1800 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Local field potential oscillations | 30 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 14,400 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Ado concentration in neurons | 50 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 14,400 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Adp concentration in neurons | 25 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 14,400 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Amp concentration in neurons | 88 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 14,400 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Imp concentration in neurons | 57 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 14,400 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Hcy concentration in neurons | 50 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 14,400 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Met concentration in neurons | 92 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 14,400 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | P-amk-alpha2 concentration | 20 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 14,400 | Wavelength, nm | 545 | Slow-wave sleep amount | 133 | ||

| 33 | Mouse | 0.25 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 630 | Crossing numbers | 40 | [278] |

| Mouse | 0.25 | SAMP8 aging model | Light | Cranial | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 630 | Crossing numbers | 36 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 630 | Escape latency | 16 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 630 | Brain fdh protein expression | 20 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | SAMP8 aging model | Light | Cranial | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 630 | Brain fdh protein expression | 117 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Healthy | Light | Cranial | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 630 | Brain catalase protein expression | 80 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | SAMP8 aging model | Light | Cranial | 72,000 | Wavelength, nm | 630 | Brain catalase protein expression | 255 | ||

| 34 | Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | M-cgf cytokine expression | 100 | [263] |

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Il-6 cytokine expression | 500 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Mig cytokine expression | 52 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Il-4 cytokine expression | 77 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Ifn-gamma cytokine expression | 2400 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Il-12 p70 cytokine expression | 50 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gm-csf cytokine expression | 79 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Il-7 cytokine expression | 100 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Il-1beta cytokine expression | 22 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Gm-csf secretion | 100 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Il-2 secretion | 30 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Il-12 p70 secretion | 60 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Eotaxin secretion | 40 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Tnfapha secretion | 100 | ||

| Mouse | 0.2 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Mcp1 secretion | 180 | ||

| 35 | Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 108,000 | “-” | “-” | Number of shocks to learning | 75 | [206] |

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 108,000 | “-” | “-” | Brdu + cells number in dg region | 89 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 108,000 | “-” | “-” | Dcx + cells number in dg region | 86 | ||

| Mouse | 0.5 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 108,000 | “-” | “-” | Brdu + dcx + cells number in dg region | 70 | ||

| 36 | Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Lighting and audio | Visually | 10 | “-” | “-” | Abeta1-42 amyloid concentration solible | 55 | [37] |

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Lighting and audio | Visually | 10 | “-” | “-” | Abeta1-42 amyloid concentration insolible | 35 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Lighting and audio | Visually | 10 | “-” | “-” | Plague numbers in ac | 41 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Audio | “-” | 10 | “-” | “-” | Plague numbers in ca1 | 50 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Audio | “-” | 10 | “-” | “-” | Plague core area in ac | 55 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Audio | “-” | 10 | “-” | “-” | Plague core area in ca1 | 45 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Audio | “-” | 10 | “-” | “-” | Abeta 12f4 amyloid concentration in ac | 45 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Audio | “-” | 10 | “-” | “-” | Abeta 12f4 amyloid concentration in ca1 | 40 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Audio | “-” | 10 | “-” | “-” | Sb100b + astrocytes count in ac | 26 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Audio | “-” | 10 | “-” | “-” | Sb100b + astrocytes count in ca1 | 12 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Audio | “-” | 10 | “-” | “-” | Gfab + astrocyte count in ac | 38 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Audio | “-” | 10 | “-” | “-” | Gfab + astrocyte count in ca1 | 17 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Audio | “-” | 10 | “-” | “-” | Lrp1-abeta colocalization | 157 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Lighting and audio | Visually | 10 | “-” | “-” | Microglia cell body diameter | 110 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Lighting and audio | Visually | 10 | “-” | “-” | Microglia avarage processes leunght | 25 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Lighting and audio | Visually | 10 | “-” | “-” | Microglia count | 95 | ||

| Mouse | 0.1 7 | BA | Lighting and audio | Visually | 10 | “-” | “-” | Migroglia per plague rate | 33 | ||

| 37 | Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 725 | Microglia cell body diameter | 75 | [39] |

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 725 | Process length | 40 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 725 | Alpha-beta + microglia | 42 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 725 | Plague count | 69 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 725 | Plague core area | 65 | ||

| 38 | Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Discrimination index | 22 | [40] |

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Latency in behavior test | 26 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Latency in behavior test | 10 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Number of plagues in hpc | 25 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Number of plagues in hpc | 20 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Number of plagues in ca1 | 43 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Aplhabeta load in hpc | 53 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Aplhabeta load in ca1 | 33 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Vessel-associated microglia | 7 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Vessel-associated microglia | 11 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Perivascilar microglia | 9 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Perivascilar microglia | 9 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Pverg concentration | 40 | ||

| Mouse | 0.8 | BA | Light | Cranial | 5,184,000 | Wavelength, nm | 1070 | Perk concentration | 45 | ||

| 39 | Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Total eeg power in m1 | 150 | [41] |

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Total eeg power in pta | 39 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Theta rhythm power in m1 | 120 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Theta rhythm power in pta | 300 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Beta rhythm power in m1 | 150 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Beta rhythm power in pta | 700 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Gamma rhythm power in m1 | 150 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Gamma rhythm power in pta | 233 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Blood flow | 33 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Brain swelling | 125 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Contralesional foot faults | 60 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Contralesional foot faults | 80 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | Stroke | Light | Cranial | 2880 | Wavelength, nm | 473 | Neurodeficite scope | 50 | ||

| 40 | Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Alpha beta1-40 amyloid content | 55 | [58] |

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Alpha beta1-42 amyloid content | 45 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | App ntf content | 25 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | App ctfs content | 20 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Aplha beta maen intensity value | 40 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Eea1 mean intensity value | 35 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Csf1 gene expression | 340 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Csf11r gene expression | 230 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Csf2ra gene expression | 50 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Icam1 gene expression | 40 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | B2m | 250 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Spp1 gene expression | 120 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Lyz2 gene expression | 290 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Cd68 gene expression | 210 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Irf7 gene expression | 220 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Bst2 gene expression | 130 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Microglia count | 114 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Microglia aβ+ | 187 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Microglia cell body diameter | 130 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Cranial | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 4793 | Process length | 60 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Alpha beta1-40 amyloid content | 65 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Alpha beta1-42 amyloid content | 70 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Microglia cell body diameter | 70 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Process length | 40 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Microglia aβ+ | 57 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Plaque number | 64 | ||

| Mouse | 0.25 | BA | Light | Visually | 3600 | Wavelength, nm | 555 | Plaque core area | 65 | ||

| 41 | Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 2 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 5 | [117] |

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 3.5 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 5 | ||

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 6 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 10 | ||

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 9.7 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 20 | ||

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 16.3 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 160 | ||

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 35.9 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 390 | ||

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 50.3 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 500 | ||

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 72 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg | 630 | ||

| 42 | Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 50.3 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg in v1 lfp | 600 | [116] |

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 35.9 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg in v1 lfp | 1000 | ||

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 16.3 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg in v1 lfp | 550 | ||

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 9.7 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg in v1 lfp | 200 | ||

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 6.1 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg in v1 lfp | 150 | ||

| Rhesus macaque | 3 | Healthy | Light | Visually | 10 | Michelson contrast, % | 3.7 | Gamma-rhythm power by meg in v1 lfp | 20 |

References

- Gudkov, S.V.; Sarimov, R.M.; Astashev, M.E.; Pishchalnikov, R.Y.; Yanykin, D.V.; Simakin, A.V.; Shkirin, A.V.; Serov, D.A.; Konchekov, E.M.; Gusein-zade Namik Guseynaga, O.; et al. Modern physical methods and technologies in agriculture. Physics-Uspekhi 2023, 67, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, N.A.; Burmistrov, D.E.; Shumeyko, S.A.; Gudkov, S.V. Fertilizers Based on Nanoparticles as Sources of Macro- and Microelements for Plant Crop Growth: A Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmistrov, D.E.; Shumeyko, S.A.; Semenova, N.A.; Dorokhov, A.S.; Gudkov, S.V. Selenium Nanoparticles (Se NPs) as Agents for Agriculture Crops with Multiple Activity: A Review. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmistrov, D.E.; Gudkov, S.V.; Franceschi, C.; Vedunova, M.V. Sex as a Determinant of Age-Related Changes in the Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkov, S.V.; Burmistrov, D.E.; Kondakova, E.V.; Sarimov, R.M.; Yarkov, R.S.; Franceschi, C.; Vedunova, M.V. An emerging role of astrocytes in aging/neuroinflammation and gut-brain axis with consequences on sleep and sleep disorders. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 83, 101775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Lee, G.; Zhong, K.; Fonseca, J.; Taghva, K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2021. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2021, 7, 12179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, C.; Cheng, F. Global and regional economic costs of dementia: A systematic review. Lancet 2017, 390, S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.R.; Voytek, B. Brain Oscillations and the Importance of Waveform Shape. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathalon, D.H.; Sohal, V.S. Neural Oscillations and Synchrony in Brain Dysfunction and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Watrous, A.J.; Patel, A.; Jacobs, J. Theta and Alpha Oscillations Are Traveling Waves in the Human Neocortex. Neuron 2018, 98, 1269–1281.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, A.; Wang, S.; Huang, A.; Qiu, C.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Deng, B. The role of gamma oscillations in central nervous system diseases: Mechanism and treatment. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 962957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başar, E.; Başar-Eroğlu, C.; Karakaş, S.; Schürmann, M. Brain oscillations in perception and memory. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2000, 35, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, F.; Wibral, M.; Mohr, H.M.; Singer, W.; Uhlhaas, P.J. Gamma-Band Activity in Human Prefrontal Cortex Codes for the Number of Relevant Items Maintained in Working Memory. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 12411–12420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, O.K.; Maffei, A. From Hiring to Firing: Activation of Inhibitory Neurons and Their Recruitment in Behavior. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhorn, R.; Bauer, R.; Jordan, W.; Brosch, M.; Kruse, W.; Munk, M.; Reitboeck, H.J. Coherent oscillations: A mechanism of feature linking in the visual cortex? Biol. Cybern. 1988, 60, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, O.J.; Cash, S.S. Finding synchrony in the desynchronized EEG: The history and interpretation of gamma rhythms. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 49503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wei, Y.; He, K.; Gao, Q. The Effects and Safety of Gamma Rhythm Stimulation on Cognitive Function in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Wu, C.; Parker, E.; Zhu, J.; Liu, T.C.-Y.; Duan, R.; Yang, L. Mystery of gamma wave stimulation in brain disorders. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiesinga, P.H.; Fellous, J.-M.; Salinas, E.; José, J.V.; Sejnowski, T.J. Inhibitory synchrony as a mechanism for attentional gain modulation. J. Physiol.-Paris 2004, 98, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonoudiou, P.; Tan, Y.L.; Kontou, G.; Upton, A.L.; Mann, E.O. Parvalbumin and Somatostatin Interneurons Contribute to the Generation of Hippocampal Gamma Oscillations. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 7668–7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzsáki, G.; Wang, X.-J. Mechanisms of Gamma Oscillations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, N.; Pi, H.J.; Sousa, V.H.; Waters, J.; Fishell, G.; Kepecs, A.; Osten, P. A developmental cell-type switch in cortical interneurons leads to a selective defect in cortical oscillations. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaikkan, C.; Tsai, L.-H. Gamma Entrainment: Impact on Neurocircuits, Glia, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Trends Neurosci. 2020, 43, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyna, T.; Gerges, C. Clinical Management of Bile Duct Diseases: Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound in a Personalized Approach. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasztóczi, B.; Klausberger, T. Layer-Specific GABAergic Control of Distinct Gamma Oscillations in the CA1 Hippocampus. Neuron 2014, 81, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, M.; Rouleau, E.A.M.Y.; van der Gaag, S.; Zutt, R.; Hoffmann, C.F.; van der Gaag, N.A.; van Essen, T.A.; Schouten, A.C.; Contarino, M.F. Decoding finely-tuned gamma oscillations in chronic deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaru, M.; Hahn, A.; Shcherbakova, M.; Little, S.; Neumann, W.-J.; Abbasi-Asl, R.; Starr, P.A. Deep brain stimulation-entrained gamma oscillations in chronic home recordings in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Stimul. 2025, 18, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Tsai, L.-H. Innovations in noninvasive sensory stimulation treatments to combat Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS Biol. 2025, 23, e3003046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traikapi, A.; Konstantinou, N. Gamma Oscillations in Alzheimer’s Disease and Their Potential Therapeutic Role. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 782399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, D.C.; Wilson, L.B. γ-Band Abnormalities as Markers of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Biomark. Med. 2014, 8, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzner, C.; Mäki-Marttunen, T.; Karni, G.; McMahon-Cole, H.; Steuber, V. The effect of alterations of schizophrenia-associated genes on gamma band oscillations. Schizophrenia 2022, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, J.M.; McCarley, R.W. Gamma band oscillations. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palop, J.J.; Mucke, L. Network abnormalities and interneuron dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strüber, D.; Herrmann, C.S. Modulation of gamma oscillations as a possible therapeutic tool for neuropsychiatric diseases: A review and perspective. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2020, 152, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manippa, V.; Palmisano, A.; Filardi, M.; Vilella, D.; Nitsche, M.A.; Rivolta, D.; Logroscino, G. An update on the use of gamma (multi)sensory stimulation for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1095081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorell, A.J.; Paulson, A.L.; Suk, H.-J.; Abdurrob, F.; Drummond, G.T.; Guan, W.; Young, J.Z.; Kim, D.N.-W.; Kritskiy, O.; Barker, S.J.; et al. Multi-sensory Gamma Stimulation Ameliorates Alzheimer’s-Associated Pathology and Improves Cognition. Cell 2019, 177, 256–271.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soula, M.; Martín-Ávila, A.; Zhang, Y.; Dhingra, A.; Nitzan, N.; Sadowski, M.J.; Gan, W.-B.; Buzsáki, G. Forty-hertz light stimulation does not entrain native gamma oscillations in Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.C.; Martorell, A.J.; Douglas, J.M.; Abdurrob, F.; Attokaren, M.K.; Tipton, J.; Mathys, H.; Adaikkan, C.; Tsai, L.-H. Noninvasive 40-Hz light flicker to recruit microglia and reduce amyloid beta load. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 1850–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Weng, X.; Han, H.; Huang, Y.; Suo, Y.; Chen, L.; et al. Microglia modulation with 1070-nm light attenuates Aβ burden and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Light Sci. Appl. 2021, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, M.; Xiao, D.; Jativa Vega, M.; Hu, H.; Vanni, M.P.; Bernier, L.-P.; LeDue, J.; MacVicar, B.; Murphy, T.H. Gamma frequency activation of inhibitory neurons in the acute phase after stroke attenuates vascular and behavioral dysfunction. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obleser, J.; Kayser, C. Neural Entrainment and Attentional Selection in the Listening Brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheer, D.E. Focused arousal and the cognitive 40-Hz event-related potentials: Differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1989, 317, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bressler, S.L.; Freeman, W.J. Frequency analysis of olfactory system EEG in cat, rabbit, and rat. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1980, 50, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galambos, R.; Makeig, S.; Talmachoff, P.J. A 40-Hz auditory potential recorded from the human scalp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 2643–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferster, D. Orientation selectivity of synaptic potentials in neurons of cat primary visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 1986, 6, 1284–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyer, J.J.; Montaron, M.F.; Vahnée, J.M.; Albert, M.P.; Rougeul, A. Anatomical localization of cortical beta rhythms in cat. Neuroscience 1987, 22, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.M.; Singer, W. Stimulus-specific neuronal oscillations in orientation columns of cat visual cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 1698–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.M.; König, P.; Engel, A.K.; Singer, W. Oscillatory responses in cat visual cortex exhibit inter-columnar synchronization which reflects global stimulus properties. Nature 1989, 338, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.K.; König, P.; Kreiter, A.K.; Schillen, T.B.; Singer, W. Temporal coding in the visual cortex: New vistas on integration in the nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1992, 15, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub, R.D.; Whittington, M.A.; Stanford, I.M.; Jefferys, J.G.R. A mechanism for generation of long-range synchronous fast oscillations in the cortex. Nature 1996, 383, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub, R.D.; Jefferys, J.G.R.; Whittington, M.A. Simulation of Gamma Rhythms in Networks of Interneurons and Pyramidal Cells. J. Comput. Neurosci. 1997, 4, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.A.; Müller, H.J. Synchronous Information Presented in 40-HZ Flicker Enhances Visual Feature Binding. Psychol. Sci. 1998, 9, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, C.S. Human EEG responses to 1–100 Hz flicker: Resonance phenomena in visual cortex and their potential correlation to cognitive phenomena. Exp. Brain Res. 2001, 137, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadler, M.D.; Tzilivaki, A.; Schmitz, D.; Alle, H.; Geiger, J.R.P. Gamma oscillation plasticity is mediated via parvalbumin interneurons. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onorato, I.; Tzanou, A.; Schneider, M.; Uran, C.; Broggini, A.C.; Vinck, M. Distinct roles of PV and Sst interneurons in visually induced gamma oscillations. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Hu, B.-W.; Li, X.-M.; Huang, H. Rethinking parvalbumin: From passive marker to active modulator of hippocampal circuits. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2025, 19, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaccarino, H.F.; Singer, A.C.; Martorell, A.J.; Rudenko, A.; Gao, F.; Gillingham, T.Z.; Mathys, H.; Seo, J.; Kritskiy, O.; Abdurrob, F.; et al. Gamma frequency entrainment attenuates amyloid load and modifies microglia. Nature 2016, 540, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajji, T.K.; Chan, D.; Suk, H.-J.; Jackson, B.L.; Milman, N.P.; Stark, D.; Klerman, E.B.; Kitchener, E.; Fernandez Avalos, V.S.; de Weck, G.; et al. Gamma frequency sensory stimulation in mild probable Alzheimer’s dementia patients: Results of feasibility and pilot studies. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Qin, X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X. 40 Hz Light Flicker Promotes Learning and Memory via Long Term Depression in Wild-Type Mice. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 84, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Duque, C.; Chan, D.; Kahn, M.C.; Murdock, M.H.; Tsai, L.H. Audiovisual gamma stimulation for the treatment of neurodegeneration. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 295, 146–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaikkan, C.; Middleton, S.J.; Marco, A.; Pao, P.-C.; Mathys, H.; Kim, D.N.-W.; Gao, F.; Young, J.Z.; Suk, H.-J.; Boyden, E.S.; et al. Gamma Entrainment Binds Higher-Order Brain Regions and Offers Neuroprotection. Neuron 2019, 102, 929–943.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimenser, A.; Hempel, E.; Travers, T.; Strozewski, N.; Martin, K.; Malchano, Z.; Hajós, M. Sensory-Evoked 40-Hz Gamma Oscillation Improves Sleep and Daily Living Activities in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 746859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirakittayakorn, N.; Wongsawat, Y. Brain responses to 40-Hz binaural beat and effects on emotion and memory. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2017, 120, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.T.; Liang, J.; Zhou, C.; Su, J. Gamma Oscillations Facilitate Effective Learning in Excitatory-Inhibitory Balanced Neural Circuits. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 6668175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-S.; Park, H.-S.; Kim, C.-J.; Kang, H.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Baek, S.-S.; Kim, T.-W. Physical exercise during exposure to 40-Hz light flicker improves cognitive functions in the 3xTg mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, A.; Garza, K.M.; Shridhar, A.; He, C.; Bitarafan, S.; Pybus, A.; Wang, Y.; Snyder, E.; Goodson, M.C.; Franklin, T.C.; et al. Brain rhythms control microglial response and cytokine expression via NF-κB signaling. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadf5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, B.; Fujioka, T. 40-Hz oscillations underlying perceptual binding in young and older adults. Psychophysiology 2016, 53, 974–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Yu, M.; Lin, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhuo, Z.; Cheng, N.; Wang, M.; Tang, Y.; Wang, L.; Hou, S.-T. Rhythmic light flicker rescues hippocampal low gamma and protects ischemic neurons by enhancing presynaptic plasticity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, M.H.; Yang, C.-Y.; Sun, N.; Pao, P.-C.; Blanco-Duque, C.; Kahn, M.C.; Kim, T.; Lavoie, N.S.; Victor, M.B.; Islam, M.R.; et al. Multisensory gamma stimulation promotes glymphatic clearance of amyloid. Nature 2024, 627, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarimov, R.M.; Serov, D.A.; Gudkov, S.V. Biological Effects of Magnetic Storms and ELF Magnetic Fields. Biology 2023, 12, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Lee, K.; Park, J.; Bae, J.B.; Kim, S.-S.; Kim, D.-W.; Woo, S.J.; Yoo, S.; Kim, K.W. Optimal flickering light stimulation for entraining gamma rhythms in older adults. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A.A.; Majid, M.A.; Mustafa, B.A. Legibility of Web Page on Full High Definition Display. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science Applications and Technologies, Kuching, Malaysia, 23–24 December 2013; pp. 521–524. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Lacambra, M.; Orduna-Hospital, E.; Arcas-Carbonell, M.; Sánchez-Cano, A. Effects of Light on Visual Function, Alertness, and Cognitive Performance: A Computerized Test Assessment. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, C.; Pattison, P.M.; Houser, K.; Herf, M.; Phillips, A.J.K.; Wright, K.P.; Skene, D.J.; Brainard, G.C.; Boivin, D.B.; Glickman, G. A Review of Human Physiological Responses to Light: Implications for the Development of Integrative Lighting Solutions. Leukos 2021, 18, 387–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, M. Changing Colour Preferences with Ageing: A Comparative Study on Younger and Older Native Germans Aged 19–90 Years. Gerontology 2001, 47, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitschan, M.; Yokoyama, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Kojima, T.; Horai, R.; Kato, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Sato, H.; Mitamura, M.; Tanaka, K.; et al. Age-related changes of color visual acuity in normal eyes. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W. An algorithm for the EEG frequency architecture of consciousness and brain body coupling. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 66103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, P. Rhythms for Cognition: Communication through Coherence. Neuron 2015, 88, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murty, D.V.P.S.; Shirhatti, V.; Ravishankar, P.; Ray, S. Large Visual Stimuli Induce Two Distinct Gamma Oscillations in Primate Visual Cortex. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 2730–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arutiunian, V.; Arcara, G.; Buyanova, I.; Gomozova, M.; Dragoy, O. The age-related changes in 40 Hz Auditory Steady-State Response and sustained Event-Related Fields to the same amplitude-modulated tones in typically developing children: A magnetoencephalography study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2022, 43, 5370–5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grachev, I.D.; Apkarian, A.V. Aging alters regional multichemical profile of the human brain: An in vivo1H-MRS study of young versus middle-aged subjects. J. Neurochem. 2008, 76, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumaraswamy, S.D.; Singh, K.D. Spatiotemporal frequency tuning of BOLD and gamma band MEG responses compared in primary visual cortex. NeuroImage 2008, 40, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, P.J.; Sekuler, R.; Sekuler, A.B. The effects of aging on motion detection and direction identification. Vis. Res. 2007, 47, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, L.R.; Taylor, C.P.; Sekuler, A.B.; Bennett, P.J. Aging Reduces Center-Surround Antagonism in Visual Motion Processing. Neuron 2005, 45, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, A.G.; Wang, Y.; Pu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Y. GABA and Its Agonists Improved Visual Cortical Function in Senescent Monkeys. Science 2003, 300, 812–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmolesky, M.T.; Wang, Y.; Pu, M.; Leventhal, A.G. Degradation of stimulus selectivity of visual cortical cells in senescent rhesus monkeys. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murty, D.V.P.S.; Manikandan, K.; Kumar, W.S.; Ramesh, R.G.; Purokayastha, S.; Javali, M.; Rao, N.P.; Ray, S. Gamma oscillations weaken with age in healthy elderly in human EEG. NeuroImage 2020, 215, 116826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkov, S.V.; Pustovoy, V.I.; Sarimov, R.M.; Serov, D.A.; Simakin, A.V.; Shcherbakov, I.A. Diversity of Effects of Mechanical Influences on Living Systems and Aqueous Solutions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, Z.; Gupta, P.B.; Li, D.R.; Nayak, R.U.; Govindarajan, P. Rapid Response EEG: Current State and Future Directions. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2022, 22, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohenkohl, G.; Bosman, C.A.; Fries, P. Gamma Synchronization between V1 and V4 Improves Behavioral Performance. Neuron 2018, 100, 953–963.e953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astashev, M.; Serov, D.; Gudkov, S. Application of Spectral Methods of Analysis for Description of Ultradian Biorhythms at the Levels of Physiological Systems, Cells and Molecules (Review). Mathematics 2023, 11, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pack, C.; Han, C.; Wang, T.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Dai, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Yang, G.; et al. Multiple gamma rhythms carry distinct spatial frequency information in primary visual cortex. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misselhorn, J.; Schwab, B.C.; Schneider, T.R.; Engel, A.K. Synchronization of Sensory Gamma Oscillations Promotes Multisensory Communication. eNeuro 2019, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.; McDermott, B.; Oliveira, B.L.; O’Brien, A.; Coogan, D.; Lang, M.; Moriarty, N.; Dowd, E.; Quinlan, L.; Mc Ginley, B.; et al. Gamma Band Light Stimulation in Human Case Studies: Groundwork for Potential Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 70, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Park, Y.; Suh, S.W.; Kim, S.-S.; Kim, D.-W.; Lee, J.; Park, J.; Yoo, S.; Kim, K.W. Optimal flickering light stimulation for entraining gamma waves in the human brain. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, B.-K.; Dähne, S.; Ahn, M.-H.; Noh, Y.-K.; Müller, K.-R. Decoding of top-down cognitive processing for SSVEP-controlled BMI. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, D. An Effect of Stimulus Colour on Average Steady-state Potentials evoked in Man. Nature 1966, 210, 1056–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tello, R.J.M.G.; Müller, S.M.T.; Ferreira, A.; Bastos, T.F. Comparison of the influence of stimuli color on Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials. Res. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 31, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, A.; Williams, D.R. The arrangement of the three cone classes in the living human eye. Nature 1999, 397, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, A.; Metha, A.B.; Lennie, P.; Williams, D.R. Packing arrangement of the three cone classes in primate retina. Vis. Res. 2001, 41, 1291–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauch, B.J.; Peter, A.; Ehrlich, I.; Nolte, Z.; Fries, P. Human visual gamma for color stimuli. eLife 2022, 11, 75897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.; Fernández-Vargas, J.; Kita, K.; Yu, W. Influence of Stimulus Color on Steady State Visual Evoked Potentials. In Intelligent Autonomous Systems 14; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Noda, Y.; Takano, M.; Hayano, M.; Li, X.; Wada, M.; Nakajima, S.; Mimura, M.; Kondo, S.; Tsubota, K. Photobiological Neuromodulation of Resting-State EEG and Steady-State Visual-Evoked Potentials by 40 Hz Violet Light Optical Stimulation in Healthy Individuals. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, D.; Wuerger, S. Colour Constancy Across the Life Span: Evidence for Compensatory Mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijk, H.; Berg, S.; Sivik, L.; Steen, B. Color discrimination, color naming and color preferences in 80-year olds. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 1999, 11, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, F.; Aton, S.J. The Engram’s Dark Horse: How Interneurons Regulate State-Dependent Memory Processing and Plasticity. Front. Neural Circuits 2021, 15, 750541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloc, M.; Maffei, A. Target-Specific Properties of Thalamocortical Synapses onto Layer 4 of Mouse Primary Visual Cortex. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 15455–15465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubaker, M.; Al Qasem, W.; Pilátová, K.; Ježdík, P.; Kvašňák, E. Theta-gamma-coupling as predictor of working memory performance in young and elderly healthy people. Mol. Brain 2024, 17, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardin, J.A.; Carlén, M.; Meletis, K.; Knoblich, U.; Zhang, F.; Deisseroth, K.; Tsai, L.-H.; Moore, C.I. Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature 2009, 459, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlén, M.; Meletis, K.; Siegle, J.H.; Cardin, J.A.; Futai, K.; Vierling-Claassen, D.; Rühlmann, C.; Jones, S.R.; Deisseroth, K.; Sheng, M.; et al. A critical role for NMDA receptors in parvalbumin interneurons for gamma rhythm induction and behavior. Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 17, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulyás, A.I.; Szabó, G.G.; Ulbert, I.; Holderith, N.; Monyer, H.; Erdélyi, F.; Szabó, G.; Freund, T.F.; Hájos, N. Parvalbumin-Containing Fast-Spiking Basket Cells Generate the Field Potential Oscillations Induced by Cholinergic Receptor Activation in the Hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 15134–15145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittington, M.A.; Traub, R.D.; Kopell, N.; Ermentrout, B.; Buhl, E.H. Inhibition-based rhythms: Experimental and mathematical observations on network dynamics. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2000, 38, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segneri, M.; Bi, H.; Olmi, S.; Torcini, A. Theta-Nested Gamma Oscillations in Next Generation Neural Mass Models. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman-Hill, S. Dynamics of Striate Cortical Activity in the Alert Macaque: I. Incidence and Stimulus-dependence of Gamma-band Neuronal Oscillations. Cereb. Cortex 2000, 10, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermentrout, B.; Lowet, E.; Roberts, M.; Hadjipapas, A.; Peter, A.; van der Eerden, J.; De Weerd, P. Input-Dependent Frequency Modulation of Cortical Gamma Oscillations Shapes Spatial Synchronization and Enables Phase Coding. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]