Microbial Diversity of the Baikal Rift Zone Freshwater Alkaline Hot Springs and the Ecology of Polyextremophilic Dissimilatory Iron-Reducing Bacteria

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Enrichment Cultures

2.3. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sampling Sites

3.2. Alpha and Beta Diversity of Microbial Communities of the BRZ Hot Springs

3.2.1. Extreme Thermophilic Group

3.2.2. Thermophilic Group

3.2.3. Moderate Thermophilic Group

3.2.4. Mixed Group

3.3. Co-Occurrence Network Analysis

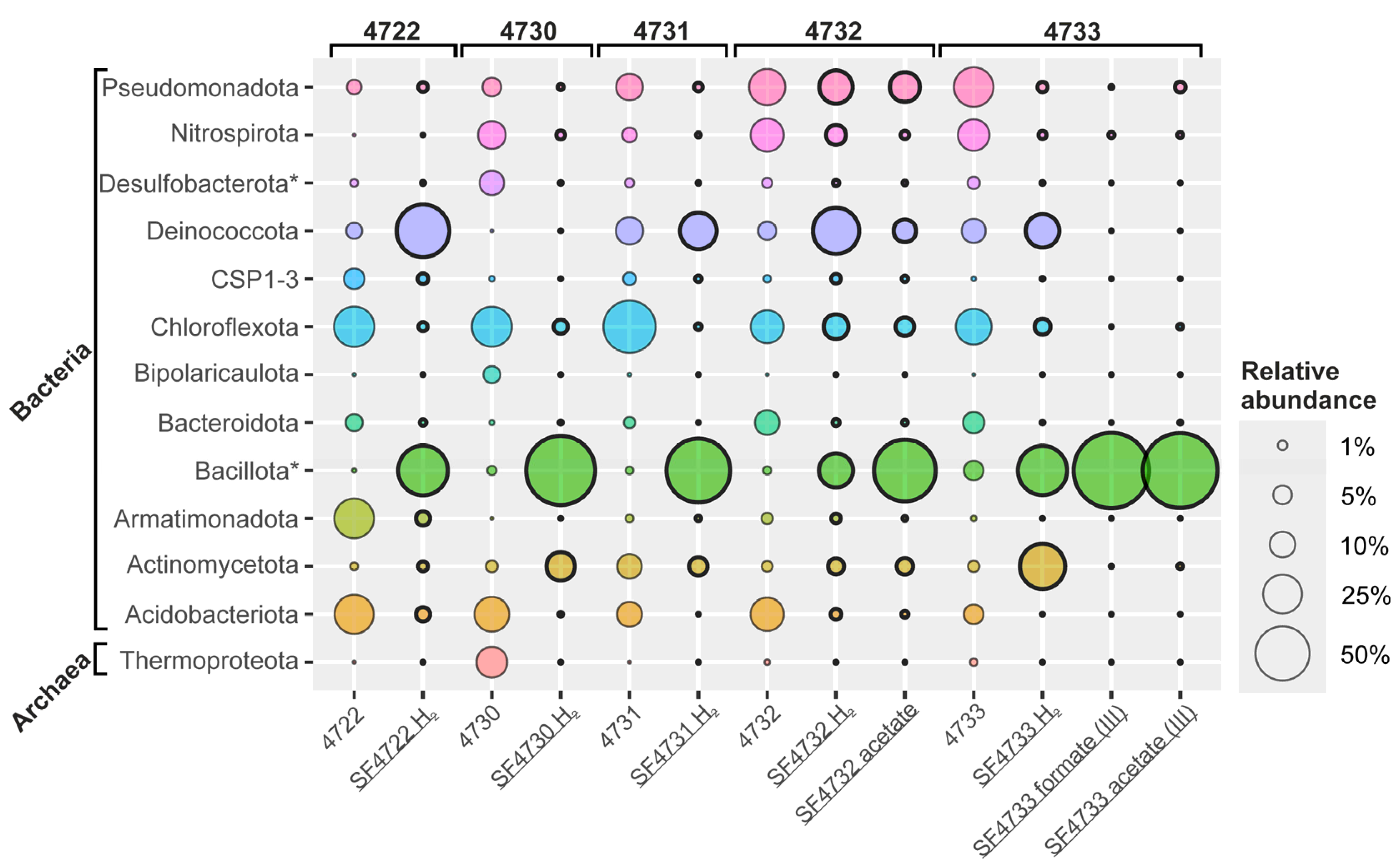

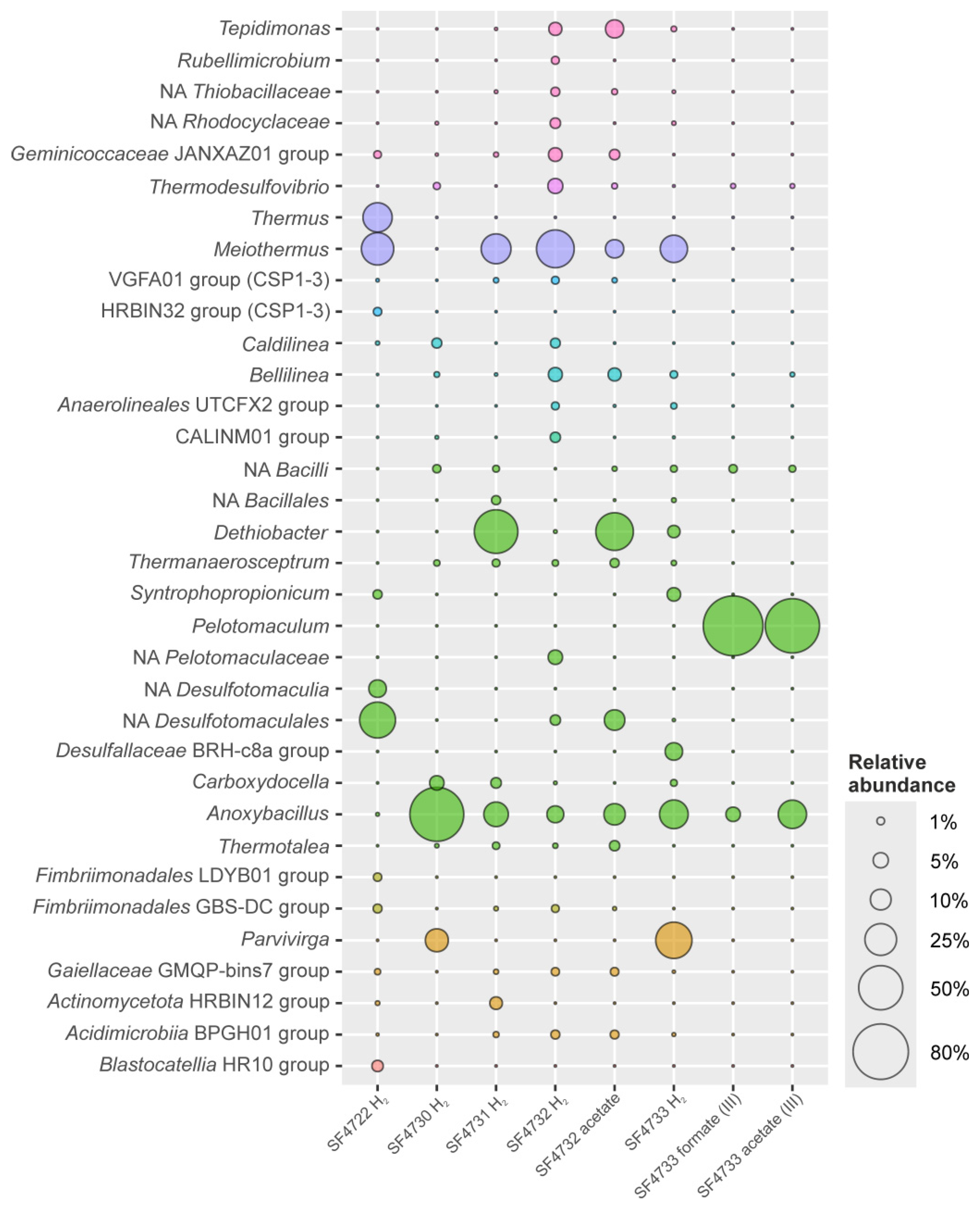

3.4. Taxonomic Diversity of Microbial Communities of the Enrichment Cultures

3.4.1. Microbial Community Structure of the Enrichment from Sample #4722 (Uro Thermal Field)

3.4.2. Microbial Community Structure of the Enrichment from Sample #4730 (Gusikha Thermal Field)

3.4.3. Microbial Community Structure of the Enrichment from Sample #4731 (Goryachinsk Thermal Field)

3.4.4. Microbial Community Structure of the Enrichment from Sample #4732 with Molecular Hydrogen and Ferrihydrite

3.4.5. Microbial Community Structure of the Enrichment from Sample #4732 with Acetate and Ferrihydrite

3.4.6. Microbial Community Structure of the Enrichment from Sample #4733 with Molecular Hydrogen and Ferrihydrite

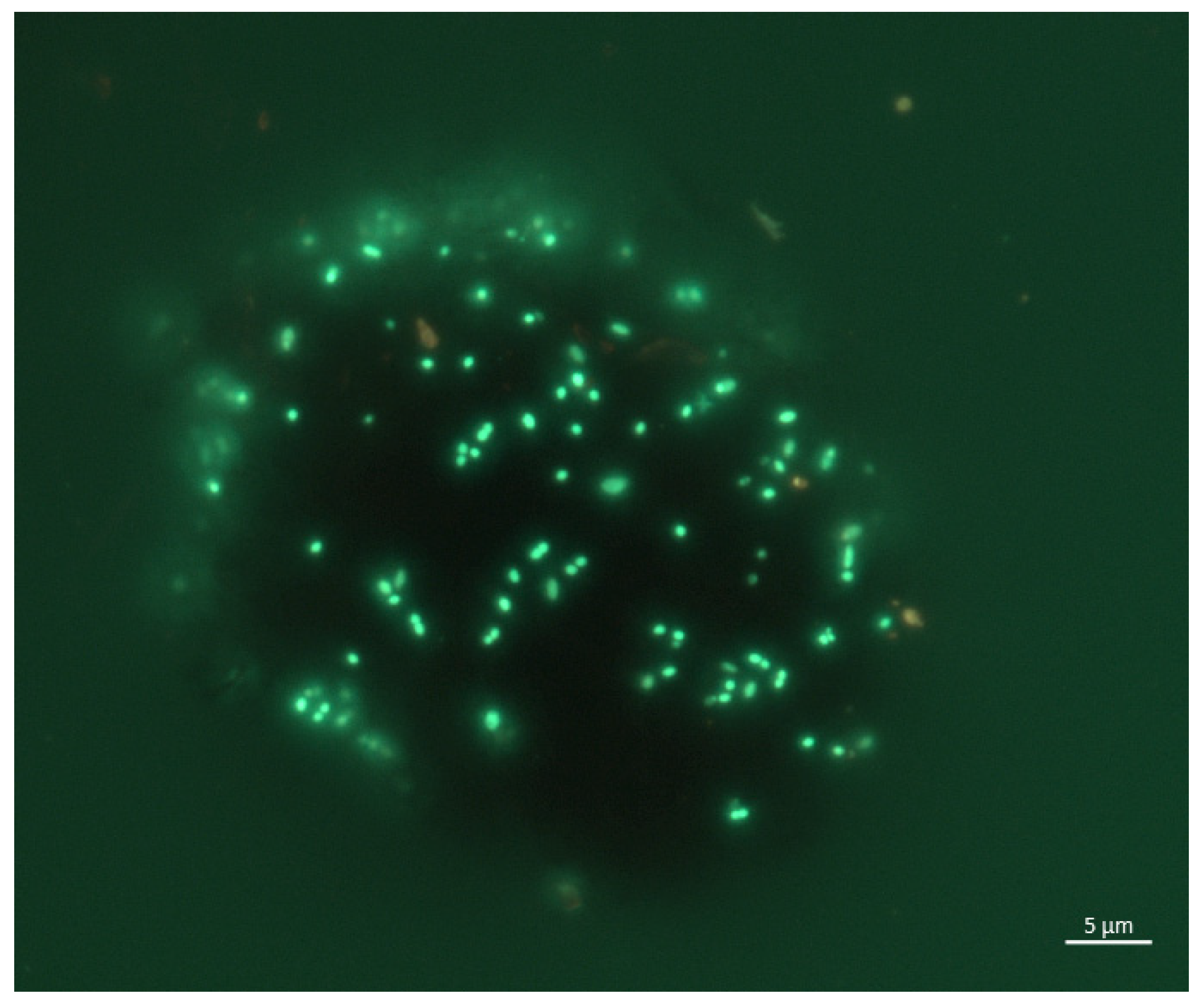

3.4.7. Microbial Community Structure of the Enrichment from Sample #4733, with Formate and Ferrihydrite (The Third Transfer)

3.4.8. Microbial Community Structure of the Enrichment from Sample #4733, with Acetate and Ferrihydrite (Third Transfer)

4. Discussion

4.1. Microbial Communities of the BRZ

4.2. Comparative Analysis of the Microbial Communities Studied with Those from Alkaline Hot Springs Worldwide

4.3. Diversity of the Alkalithermophilic Dissimilatory Iron Reducers in BRZ

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASVs | Amplicon sequence variations |

| BLAST | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| BRZ | The Baikal Rift Zone |

| BV | The Barguzin Valley |

| ET group | The Extreme Thermophilic group |

| GTDB | The Genome Taxonomy Database |

| M group | The Mixed group |

| MT | The Moderate Thermophilic group |

| ND | Not detected |

| NMDS | Non-metric multidimensional scaling |

| T group | Thermophilic group |

References

- Zippa, E.V.; Ukraintsev, A.V.; Chernyavskii, M.K.; Fedorov, I.A.; Poturay, V.A.; Domrocheva, E.V.; Mukhortina, N.A. Thermal waters in the central part of Baikal Rift Zone: Hydrogeochemistry and geothermometry (Republic of Buryatia, Russia). Geothermics 2025, 130, 103317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrentyeva, E.V.; Radnagurueva, A.A.; Banzaraktsaeva, T.G.; Bazarov, S.M.; Barkhutova, D.D.; Ulzetueva, I.D.; Chernyavsky, M.K.; Kabilov, M.R.; Khakhinov, V.V. Phylogenetic analysis of the microbial mat in the hot spring Garga (Baikal rift zone) and the diversity of natural peptidases. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2017, 21, 959–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Namsaraev, B.B.; Khakhinov, V.V.; Garmaev, E.Z.H.; Barkhutova, D.D.; Namsaraev, Z.B.; Plyusnin, A.M. Vodnye Sistemy Barguzinskoi Kotloviny (Aquatic Systems of Barguzin Depression); Buryat State University: Ulan-Ude, Russia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rozanov, A.S.; Bryanskaya, A.V.; Ivanisenko, T.V.; Malup, T.K.; Peltek, S.E. Biodiversity of the microbial mat of the Garga hot spring. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plyusnin, A.M.; Zamana, L.V.; Shvartsev, S.L.; Tokarenko, O.G.; Chernyavskii, M.K. Hydrogeochemical peculiarities of the composition of nitric thermal waters in the Baikal rift zone. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2013, 54, 647–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Dombard, D.R.; Shock, E.L.; Amend, J.P. Archaeal and bacterial communities in geochemically diverse hot springs of Yellowstone National Park, USA. Geobiology 2005, 3, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radnagurueva, A.A.; Lavrentieva, E.V.; Budagaeva, V.G.; Barkhutova, D.D.; Dunaevsky, Y.E.; Namsaraev, B.B. Organotrophic bacteria of the Baikal Rift Zone hot springs. Microbiology 2016, 85, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrentyeva, E.V.; Banzaraktsaeva, T.; Radnagurueva, A.A.; Buryukhaev, S.P.; Dambaev, V.; Baturina, O.A.; Kozyreva, L.; Barkhutova, D.D. Microbial Community of Umkhei Thermal Lake (Baikal Rift Zone) in the Groundwater Discharge Zone. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2019, 12, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrentyeva, E.V.; Banzaraktsaeva, T.G.; Dambaev, V.B.; Radnagurueva, A.A.; Kozyreva, L.P. Taxonomic composition and proteolytic potential in the microbial mat of the Uro hot spring (the Baikal rift zone). In IV All-Russian Conference with International Participation “Diversity of Soils and Biota of Northern and Central Asia”; Buryat State University: Ulan-Ude, Russia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhutova, D.D.; Buryukhaev, S.P.; Dambaev, V.B.; Tsyrenova, D.D.; Lavrentyeva, E.V. Taxonomical and functional diversity of microbial communities in two hot springs of the Baikal rift zone. IOP Sci. 2021, 908, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompantseva, E.I.; Gorlenko, V.M. Phototrophic communities in some Lake Baikal thermal springs. Mikrobiologiya 1988, 57, 841–846. [Google Scholar]

- Bryanskaya, A.V.; Namsaraev, Z.B.; Kalashnikova, O.M.; Barkhutova, D.D.; Namsaraev, B.B.; Gorlenko, V.M. Biogeochemical processes in the algal-bacterial mats of the Urinskii alkaline hot spring. Microbiology 2006, 75, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazareva, E.V.; Bryanskaya, A.V.; Zhmodik, S.M.; Kolmogorov, Y.P.; Pestunova, O.P.; Barkhutova, D.D.; Zolotarev, K.V.; Shaporenko, A.D. Elements redistribution between organic and mineral parts of microbial mats: SR-XRF research (Baikal Rift Zone). Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2009, 603, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namsaraev, B.B.; Barkhutova, D.D.; Khakhinov, V.V. Geokhimicheskaya Deyatel’nost’ Mikroorganizmov Gidroterm BRZ (Geochemical Activity of Microorganisms in the BRZ Hydrotherms); Geo: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kalashnikov, A.M.; Gaĭsin, V.A.; Sukhacheva, M.V.; Namsaraeva, B.B.; Panteleeva, A.N.; Nuianzina-Boldareva, E.N.; Kuznetsov, B.B.; Gorlenko, V.M. Anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria from microbial communities of Goryachinsk Thermal Spring (Baikal Area, Russia). Microbiology 2014, 83, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrentyeva, E.V.; Radnagurueva, A.A.; Baturina, O.A.; Khakhinov, V.V. Taxonomic Diversity of the Microbial Community in the Kuchiger Thermal Spring (Baikal Rift Zone). Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2024, 17, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namsaraev, B.B.; Barkhutova, D.D.; Danilova, E.V.; Dagurova, O.P.; Namsaraev, Z.B.; Balzhiin, T.; Ayush, O. Structure and Functioning of Microbial Community of Mineral Springs in Central Asia. Mong. J. Biol. Sci. 2003, 1, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanov, I.I.; Kadnikov, V.V.; Lukina, A.P.; Danilova, E.V.; Sokolyanskaya, L.O.; Ravin, N.V.; Karnachuk, O.V. Low-Abundance Sulfidogenic Bacteria Carry out Intensive Sulfate Reduction in Terrestrial Hydrotherms of the Barguzin Valley. Microbiology 2023, 92 (Suppl. S1), 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, S.L.; Bonsall, E.; Cockell, C.S. Limitations of microbial iron reduction under extreme conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 46, fuac033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolin, E.A.; Wolin, M.J.; Wolfe, R.S. Formation of methane by bacterial extracts. J. Biol. Chem. 1963, 238, 2882–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevbrin, V.V.; Zavarzin, G.A. The influence of sulfur compounds on the growth of halophilic homoacetic bacterium Acetohalobium arabaticum. Microbiology 1992, 61, 563–571. [Google Scholar]

- Zavarzina, D.G.; Klyukina, A.A.; Merkel, A.Y.; Maslova, T.A.; Maslov, A.A. Alkalo-thermophilic iron-reducing bacteria of the Goryachinskoe thermal water deposit. Microbiology 2024, 93, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohl, D.M.; Vangay, P.; Garbe, J.; MacLean, A.; Hauge, A.; Becker, A.; Gould, T.J.; Clayton, J.B.; Johnson, T.J.; Hunter, R.; et al. Systematic improvement of amplicon marker gene methods for increased accuracy in microbiome studies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.; Rime, T.; Phillips, M.; Stierli, B.; Hajdas, I.; Widmer, F.; Hartmann, M. Microbial diversity in European alpine permafrost and active layers. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, A.Y.; Tarnovetskii, I.Y.; Podosokorskaya, O.A.; Toshchakov, S.V. Analysis of 16S rRNA primer systems for profiling of thermophilic microbial communities. Microbiology 2019, 88, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadrosh, D.W.; Ma, B.; Gajer, P.; Sengamalay, N.; Ott, S.; Brotman, R.M.; Ravel, J. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome 2014, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zippa, E.V.; Plyusnin, A.M.; Shvartsev, S.L. The chemical and isotopic compositions of thermal waters and gases in the Republic of Buryatia. In Proceedings of the 16th International Symposium on Water-Rock Interaction (WRI-16) and 13th International Symposium on Applied Isotope Geochemistry (1st IAGC International Conference), Tomsk, Russia, 21–26 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shima, S.; Suzuki, K.I. Hydrogenobacter acidophilus sp. nov., a thermoacidophilic, aerobic, hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium requiring elemental sulfur for growth. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1993, 43, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skimisdottir, S.; Hreggvidsson, G.O.; Holst, O.; Kristjansson, J.K. A new ecological adaptation to high sulfide by a Hydrogenobacter sp. growing on sulfur compounds but not on hydrogen. Microbiol. Res. 2001, 156, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeytun, A.; Sikorski, J.; Nolan, M.; Lapidus, A.; Lucas, S.; Han, J.; Tice, H.; Cheng, J.-F.; Tapia, R.; Goodwin, L.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Hydrogenobacter thermophilus type strain (TK-6). Stand. Genomic Sci. 2011, 4, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, G.E.; Liu, Y.; Ferrera, I.; Beveridge, T.J.; Reysenbach, A.L. Sulfurihydrogenibium kristjanssonii sp. nov., a hydrogen- and sulfur-oxidizing thermophile isolated from a terrestrial Icelandic hot spring. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodsworth, J.A.; Ong, J.C.; Williams, A.J.; Dohnalkova, A.C.; Hedlund, B.P. Thermocrinis jamiesonii sp. nov., a thiosulfate-oxidizing, autotropic thermophile isolated from a geothermal spring. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 4769–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.H.; Liew, K.J.; Sani, R.K.; Samanta, D.; Pointing, S.B.; Chan, K.G.; Goh, K.M. Microbial diversity and metabolic predictions of high-temperature streamer biofilms using metagenome-assembled genomes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, L.; Rainey, F.A.; da Costa, M.S. Thermus. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria (Online); John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2018; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Matsuzawa, H.; Muramatsu, M.; Meng, X.Y.; Hanada, S.; Mori, K.; Kamagata, Y. Armatimonas rosea gen. nov., sp. nov., of a novel bacterial phylum, Armatimonadetes phyl. nov., formally called the candidate phylum OP10. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61 Pt 6, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Dunfield, P.F.; Morgan, X.C.; Crowe, M.A.; Houghton, K.M.; Vyssotski, M.; Ryan, J.L.J.; Lagutin, K.; McDonald, I.R.; Stott, M.B. Chthonomonas calidirosea gen. nov., sp. nov., an aerobic, pigmented, thermophilic micro-organism of a novel bacterial class, Chthonomonadetes classis nov., of the newly described phylum Armatimonadetes originally designated candidate division OP10. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61 Pt 10, 2482–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, W.T.; Hu, Z.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Rhee, S.K.; Meng, H.; Lee, S.T.; Quan, Z.X. Description of Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli gen. nov., sp. nov. within the Fimbriimonadia class nov., of the phylum Armatimonadetes. Antonie Van. Leeuwenhoek 2012, 102, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahon, G.; Tytgat, B.; Lebbe, L.; Carlier, A.; Willems, A. Abditibacterium utsteinense sp. nov., the first cultivated member of candidate phylum FBP, isolated from ice-free Antarctic soil samples. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 41, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Kudo, C.; Tonouchi, A. Capsulimonas corticalis gen. nov., sp. nov., an aerobic capsulated bacterium, of a novel bacterial order, Capsulimonadales ord. nov., of the class Armatimonadia of the phylum Armatimonadetes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavarzina, D.G.; Tourova, T.P.; Kuznetsov, B.B.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A.; Slobodkin, A.I. Thermovenabulum ferriorganovorum gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel thermophilic, anaerobic, endospore-forming bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52 Pt 5, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baena, S.; Patel, B.K.C. Caloramator. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria (Online); John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, F.A. Caldicellulosiruptor. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria (Online); John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, E.A.; Devereux, R.; Maki, J.S.; Gilmour, C.C.; Woese, C.R.; Mandelco, L.; Schauder, R.; Remsen, C.C.; Mitchell, R. Characterization of a new thermophilic sulfate-reducing bacterium Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii, gen. nov. and sp. nov.: Its phylogenetic relationship to Thermodesulfobacterium commune and their origins deep within the bacterial domain. Arch. Microbiol. 1994, 161, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Y.A.; Kadnikov, V.V.; Lukina, A.P.; Banks, D.; Beletsky, A.V.; Mardanov, A.V.; Sen’kina, E.I.; Avakyan, M.R.; Karnachuk, O.V.; Ravin, N.V. Characterization and Genome Analysis of the First Facultatively Alkaliphilic Thermodesulfovibrio Isolated from the Deep Terrestrial Subsurface. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltseva, A.I.; Elcheninov, A.G.; Klyukina, A.A.; Pimenov, N.V.; Novikov, A.A.; Lebedinsky, A.V.; Frolov, E.N. Thermodesulfovibrio autotrophicus sp. nov., the first autotrophic representative of the widespread sulfate-reducing genus Thermodesulfovibrio, and Thermodesulfovibrio obliviosus sp. nov. that has lost this ability. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 47, 126561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Fukui, M.; Kuever, J. Desulfofundulus. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria (Online); John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2020; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; An, L.; Nie, Y.; Wu, X.L. Diversity and Ecological Relevance of Fumarate-Adding Enzymes in Oil Reservoir Microbial Communities. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 27, e70068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, L.; Rainey, F.A.; da Costa, M.S. Meiothermus. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria (Online); John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2018; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson, B.K.; Castenholz, R.W. A phototrophic gliding filamentous bacterium of hot springs, Chloroflexus aurantiacus, gen. and sp. nov. Arch. Microbiol. 1974, 100, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, S.; Hiraishi, A.; Shimada, K.; Matsuura, K. Chloroflexus aggregans sp. nov., a filamentous phototrophic bacterium which forms dense cell aggregates by active gliding movement. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1995, 45, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaisin, V.A.; Kalashnikov, A.M.; Grouzdev, D.S.; Sukhacheva, M.V.; Kuznetsov, B.B.; Gorlenko, V.M. Chloroflexus islandicus sp. nov., a thermophilic filamentous anoxygenic phototrophic bacterium from a geyser. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.K.; Gieler, B.A.; Heisler, D.L.; Palisoc, M.M.; Williams, A.J.; Dohnalkova, A.C.; Ming, H.; Yu, T.T.; Dodsworth, J.A.; Li, W.J.; et al. Kallotenue papyrolyticum gen. nov., sp. nov., a cellulolytic and filamentous thermophile that represents a novel lineage (Kallotenuales ord. nov., Kallotenuaceae fam. nov.) within the class Chloroflexia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63 Pt 12, 4675–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekiguchi, Y.; Yamada, T.; Hanada, S.; Ohashi, A.; Harada, H.; Kamagata, Y. Anaerolinea thermophila gen. nov., sp. nov. and Caldilinea aerophila gen. nov., sp. nov., novel filamentous thermophiles that represent a previously uncultured lineage of the domain Bacteria at the subphylum level. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53 Pt 6, 1843–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grégoire, P.; Bohli, M.; Cayol, J.L.; Joseph, M.; Guasco, S.; Dubourg, K.; Cambar, J.; Michotey, V.; Bonin, P.; Fardeau, M.L.; et al. Caldilinea tarbellica sp. nov., a filamentous, thermophilic, anaerobic bacterium isolated from a deep hot aquifer in the Aquitaine Basin. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61 Pt 6, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanada, S.; Takaichi, S.; Matsuura, K.; Nakamura, K. Roseiflexus castenholzii gen. nov., sp. nov., a thermophilic, filamentous, photosynthetic bacterium that lacks chlorosomes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52 Pt 1, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segerer, A.; Langworthy, T.A.; Stetter, K.O. Thermoplasma acidophilum and Thermoplasma volcanium sp. nov. from Solfatara Fields. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1988, 10, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Saha, A.; Sar, P. Thermoplasmata and Nitrososphaeria as dominant archaeal members in acid mine drainage sediment of Malanjkhand Copper Project, India. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 1833–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltseva, A.I.; Klyukina, A.A.; Elcheninov, A.G.; Pimenov, N.V.; Rusanov, I.I.; Kublanov, I.V.; Kochetkova, T.V.; Frolov, E.N. Water and sediments of an acidic hot spring—Distinct differentiation with regard to the Microbial Community Composition and functions. Water 2023, 15, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomyakova, M.A.; Merkel, A.Y.; Mamiy, D.D.; Klyukina, A.A.; Slobodkin, A.I. Phenotypic and genomic characterization of Bathyarchaeum tardum gen. nov., sp. nov., a cultivated representative of the archaeal class Bathyarchaeia. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1214631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.J.; Saw, J.H.; Lind, A.E.; Lazar, C.S.; Hinrichs, K.U.; Teske, A.P.; Ettema, T.J. Genomic inference of the metabolism of cosmopolitan subsurface Archaea, Hadesarchaea. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Fu, L.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wegener, G.; Cheng, L.; Wang, F. Thermophilic Hadarchaeota grow on long-chain alkanes in syntrophy with methanogens. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6560, Erratum in: Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, J.F.; Carere, C.R.; Lee, C.K.; Wakerley, G.L.J.; Evans, D.W.; Button, M.; White, D.; Climo, M.D.; Hinze, A.M.; Morgan, X.C.; et al. Microbial biogeography of 925 geothermal springs in New Zealand. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podar, P.T.; Yang, Z.; Björnsdóttir, S.H.; Podar, M. Comparative Analysis of Microbial Diversity Across Temperature Gradients in Hot Springs From Yellowstone and Iceland. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes-Martins, M.C.; Keller, L.M.; Munro-Ehrlich, M.; Zimlich, K.R.; Mettler, M.K.; England, A.M.; Clare, R.; Surya, K.; Shock, E.L.; Colman, D.R.; et al. Ecological Dichotomies Arise in Microbial Communities Due to Mixing of Deep Hydrothermal Waters and Atmospheric Gas in a Circumneutral Hot Spring. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e0159821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Porta, G.; Hoppert, M.; Hallmann, C.; Schneider, D.; Reitner, J. The influence of microbial mats on travertine precipitation in active hydrothermal systems (Central Italy). Depos. Rec. 2022, 8, 165–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, D.R.; Keller, L.M.; Arteaga-Pozo, E.; Andrade-Barahona, E.; St Clair, B.; Shoemaker, A.; Cox, A.; Boyd, E.S. Covariation of hot spring geochemistry with microbial genomic diversity, function, and evolution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambura, A.K.; Mwirichia, R.K.; Kasili, R.W.; Karanja, E.N.; Makonde, H.M.; Boga, H.I. Bacteria and Archaea diversity within the hot springs of Lake Magadi and Little Magadi in Kenya. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriac, C.M.; Szekeres, E.; Rudi, K.; Baricz, A.; Hegedus, A.; Dragoş, N.; Coman, C. Differences in Temperature and Water Chemistry Shape Distinct Diversity Patterns in Thermophilic Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01363-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddar, A.; Das, S.K. Microbiological studies of hot springs in India: A review. Arch. Microbiol. 2018, 200, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escuder-Rodríguez, J.J.; DeCastro, M.E.; Saavedra-Bouza, A.; Becerra, M.; González-Siso, M.I. Insights on Microbial Communities Inhabiting Non-Volcanic Hot Springs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostešić, E.; Mitrović, M.; Kajan, K.; Marković, T.; Hausmann, B.; Orlić, S.; Pjevac, P. Microbial Diversity and Activity of Biofilms from Geothermal Springs in Croatia. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 2305–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, X.; He, M.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chen, T.; et al. Geological and hydrochemical controls on water chemistry and stable isotopes of hot springs in the Three Parallel Rivers Region, southeast Tibetan Plateau: The genesis of geothermal waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, J.K.; Peacock, J.P.; Dodsworth, J.A.; Williams, A.J.; Thompson, D.B.; Dong, H.; Wu, G.; Hedlund, B.P. Sediment microbial communities in Great Boiling Spring are controlled by temperature and distinct from water communities. ISME J. 2013, 7, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen De León, K.; Gerlach, R.; Peyton, B.M.; Fields, M.W. Archaeal and bacterial communities in three alkaline hot springs in Heart Lake Geyser Basin, Yellowstone National Park. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.C.; Murugapiran, S.K.; Hamilton, T.L. Temperature impacts community structure and function of phototrophic Chloroflexi and Cyanobacteria in two alkaline hot springs in Yellowstone National Park. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 12, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inskeep, W.P.; Jay, Z.J.; Tringe, S.G.; Herrgard, M.J.; Rusch, D.B. YNP Metagenome Project Steering Committee and Working Group Members. The YNP Metagenome Project: Environmental Parameters Responsible for Microbial Distribution in the Yellowstone Geothermal Ecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, L.; Dowd, S.E.; Davidson, K.; Kovarik, C.; VanAken, M.; Jarabek, A.; Taylor, C. Comparing microbial populations from diverse hydrothermal features in Yellowstone National Park: Hot springs and mud volcanoes. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1409664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.N.; Nishihara, A.; Lichtenberg, M.; Trampe, E.; Kawai, S.; Tank, M.; Kühl, M.; Hanada, S.; Thiel, V. Vertical Distribution and Diversity of Phototrophic Bacteria within a Hot Spring Microbial Mat (Nakabusa Hot Springs, Japan). Microbes Environ. 2019, 34, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heni, Y.; Muharni, J. Isolation and Phylogenetic Analysis of Thermophile Community Within Tanjung Sakti Hot Spring, South Sumatera, Indonesia. HAYATI J. Biosci. 2015, 22, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hongmei, J.; Aitchison, J.C.; Lacap, D.C.; Peerapornpisal, Y.; Sompong, U.; Pointing, S.B. Community phylogenetic analysis of moderately thermophilic cyanobacterial mats from China, the Philippines and Thailand. Extremophiles 2005, 9, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe-Lorío, L.; Brenes-Guillén, L.; Hernández-Ascencio, W.; Mora-Amador, R.; González, G.; Ramírez-Umaña, C.J.; Díez, B.; Pedrós-Alió, C. The influence of temperature and pH on bacterial community composition of microbial mats in hot springs from Costa Rica. Microbiologyopen 2019, 8, e893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, G.; Jiang, H.; Yang, J.; She, W.; Khan, I.; Li, W. Abundant and Rare Microbial Biospheres Respond Differently to Environmental and Spatial Factors in Tibetan Hot Springs. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hou, W.; Dong, H.; Jiang, H.; Huang, L.; Wu, G.; Zhang, C.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, H.; et al. Control of temperature on microbial community structure in hot springs of the Tibetan Plateau. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Dong, C.Z.; Dong, R.M.; Jiang, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Fang, B.; Ding, X.; Niu, L.; Li, X.; et al. Archaeal and bacterial diversity in hot springs on the Tibetan Plateau, China. Extremophiles 2011, 15, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, P.; Van Nostrand, J.D.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, D.; Wang, Y. Microbial communities and arsenic biogeochemistry at the outflow of an alkaline sulfide-rich hot spring. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.S.; Feng, Q.D.; Zhang, D.Y.; Zhu, G.L.; Yang, L. Bacterial community structure in geothermal springs on the northern edge of Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 994179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, C.; Nicol, A.; Li, P.; Planer-Friedrich, B.; Yuan, C.; Kou, Z. Different sulfide to arsenic ratios driving arsenic speciation and microbial community interactions in two alkaline hot springs. Environ. Res. 2023, 218, 115033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Reza, H.M.; Pal, S. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of bacterial community and characterization of Cr(VI) reducers from the sediments of Tantloi hot spring, India. Aquat. Biosyst. 2014, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Subudhi, E.; Sahoo, R.K.; Gaur, M. Investigation of the microbial community in the Odisha hot spring cluster based on the cultivation independent approach. Genom. Data 2016, 7, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zimik, H.V.; Farooq, S.H.; Prusty, P. Geochemical evaluation of thermal springs in Odisha, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, R.K.; Subudhi, E.; Kumar, M. Investigation of bacterial diversity of hot springs of Odisha, India. Genom. Data 2015, 6, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badhai, J.; Ghosh, T.S.; Das, S.K. Taxonomic and functional characteristics of microbial communities and their correlation with physicochemical properties of four geothermal springs in Odisha, India. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.K.; Bisht, S.S.; Kumar, N.S.; De Mandal, S. Investigations on microbial diversity of Jakrem hot spring, Meghalaya, India using cultivation-independent approach. Genom. Data 2015, 4, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.K.; Bisht, S.S.; De Mandal, S.; Kumar, N.S. Bacterial and archeal community composition in hot springs from Indo-Burma region, North-east India. AMB Express 2016, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Subudhi, E. Profiling of microbial community of Odisha hot spring based on metagenomic sequencing. Genom. Data 2016, 7, 187–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saxena, R.; Dhakan, D.B.; Mittal, P.; Waiker, P.; Chowdhury, A.; Ghatak, A.; Sharma, V.K. Metagenomic Analysis of Hot Springs in Central India Reveals Hydrocarbon Degrading Thermophiles and Pathways Essential for Survival in Extreme Environments. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S.; Padhi, S.K.; Mohanty, S.; Samanta, M.; Maiti, N.K. Analysis of the metatranscriptome of microbial communities of an alkaline hot sulfur spring revealed different gene encoding pathway enzymes associated with energy metabolism. Extremophiles 2016, 20, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Wang, S.; Dong, H.; Jiang, H.; Briggs, B.R.; Peacock, J.P.; Huang, Q.; Huang, L.; Wu, G.; Zhi, X.; et al. A comprehensive census of microbial diversity in hot springs of Tengchong, Yunnan Province China using 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Dong, H.; Hou, W.; Jiang, H.; Huang, Q.; Briggs, B.R.; Huang, L. Greater temporal changes of sediment microbial community than its waterborne counterpart in Tengchong hot springs, Yunnan Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Najar, I.N.; Sherpa, M.T.; Kumari, A.; Thakur, N. Post-monsoon seasonal variation of prokaryotic diversity in solfataric soil from the North Sikkim hot spring. Int. Microbiol. 2023, 26, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Das, S.; Jiya, N.; Sharma, A.; Saha, C.; Sharma, P.; Tamang, S.; Thakur, N. Bacterial diversity along the geothermal gradients: Insights from the high-altitude Himalayan hot spring habitats of Sikkim. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2024, 7, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Kumar, J.; Abedin, M.M.; Sahoo, D.; Pandey, A.; Rai, A.K.; Singh, S.P. Metagenomics revealing molecular profiling of community structure and metabolic pathways in natural hot springs of the Sikkim Himalaya. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomyakova, M.A.; Zavarzina, D.G.; Merkel, A.Y.; Klyukina, A.A.; Pikhtereva, V.A.; Gavrilov, S.N.; Slobodkin, A.I. The first cultivated representatives of the actinobacterial lineage OPB41 isolated from subsurface environments constitute a novel order Anaerosomatales. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1047580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavarzina, D.G.; Maslov, A.A.; Merkel, A.Y.; Kharitonova, N.A.; Klyukina, A.A.; Baranovskaya, E.I.; Baydariko, E.A.; Potapov, E.G.; Zayulina, K.S.; Bychkov, A.Y.; et al. Analogs of Precambrian microbial communities formed de novo in Caucasian mineral water aquifers. mBio 2025, 16, e0283124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.; Rainey, F.; Nobre, M.; Burghardt, J.; Da Costa, M. Meiothermus cerbereus sp. nov., a new slightly thermophilic species with high levels of 3-hydroxy fatty acids. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1997, 47, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, O.; Knapik, K.; Cerdán, M.E.; González-Siso, M.I. Metagenomics of an alkaline hot spring in Galicia (Spain): Microbial diversity analysis and screening for novel lipolytic enzymes. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woycheese, K.M.; Meyer-Dombard, D.A.R.; Cardace, D.; Argayosa, A.M.; Arcilla, C.A. Out of the dark: Tansitional subsurface-to-surface microbial diversity in a terrestrial serpentinizing seep (Manleluag, Pangasinan, the Philippines). Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieft, T.L.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Onstott, T.C.; Gorby, Y.A.; Kostandarithes, H.M.; Bailey, T.J.; Kennedy, D.W.; Li, S.W.; Plymale, A.E.; Spadoni, C.M.; et al. Dissimilatory Reduction of Fe(III) and Other Electron Acceptors by a Thermus Isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkwill, D.L.; Kieft, T.L.; Tsukuda, T.; Kostandarithes, H.M.; Onstott, T.C.; Macnaughton, S.; Bownas, J.; Fredrickson, J.K. Identification of iron-reducing Thermus strains as Thermus scotoductus. Extremophiles 2004, 8, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pikuta, E.; Cleland, D.; Tang, J. Aerobic growth of Anoxybacillus pushchinoensis K1T: Emended descriptions of A. pushchinoensis and the genus Anoxybacillus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 1561–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pikuta, E.; Lysenko, A.; Chuvilskaya, N.; Mendrock, U.; Hippe, H.; Suzina, N.; Nikitin, D.; Osipov, G.; Laurinavichius, K. Anoxybacillus pushchinensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel anaerobic, alkaliphilic, moderately thermophilic bacterium from manure, and description of Anoxybacillus flavitherms comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50, 2109–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Hao, H.H.; Zheng, J.; Chen, J.M. Fe(II)EDTA-NO reduction by a newly isolated thermophilic Anoxybacillus sp. HA from a rotating drum biofilter for NOx removal. J. Microbiol. Methods 2015, 109, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodkina, G.B.; Panteleeva, A.N.; Sokolova, T.G.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A.; Slobodkin, A.I. Carboxydocella manganica sp. nov., a thermophilic, dissimilatory Mn(IV)- and Fe(III)-reducing bacterium from a Kamchatka hot spring. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2012, 62, 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, D.Y.; Tourova, T.P.; Mussmann, M.; Muyzer, G. Dethiobacter alkaliphilus gen. nov. sp. nov., and Desulfurivibrio alkaliphilus gen. nov. sp. nov.: Two novel representatives of reductive sulfur cycle from soda lakes. Extremophiles 2008, 12, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavarzina, D.G.; Merkel, A.Y.; Klyukina, A.A.; Elizarov, I.M.; Pikhtereva, V.A.; Rusakov, V.S.; Chistyakova, N.I.; Ziganshin, R.H.; Maslov, A.A.; Gavrilov, S.N. Iron or sulfur respiration-an adaptive choice determining the fitness of a natronophilic bacterium Dethiobacter alkaliphilus in geochemically contrasting environments. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1108245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | T, °C | pH | Eh, mV | Coordinates | Number of ASVs Detected | Number of ASVs with More than 1% Abundance | Chao1 | Shannon | InvSimpson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4703 | 32 | 7.6 | −238 | 54.987511 111.118274 | 427 | 16 | 427 | 4.845 | 45.739 |

| 4704 | 42 | 9.5 | −330 | 54.987872 111.118483 | 334 | 21 | 334 | 4.365 | 33.301 |

| 4705 | 41 | 6.9 | NA | 54.882258 111.001 | 281 | 25 | 281 | 4.401 | 39.919 |

| 4707 | 74 | 7.8 | −190 | 54.32022 110.993979 | 42 | 18 | 43 | 2.641 | 8.745 |

| 4708 | 74 | 7.8 | −190 | 54.32022 110.993979 | 23 | 6 | 23 | 1.608 | 3.241 |

| 4709 | 74 | 7.8 | −190 | 54.32022 110.993979 | 68 | 15 | 68 | 2.334 | 4.780 |

| 4711 | 72 | 7.9 | −160 | 54.320076 110.993912 | 76 | 16 | 76 | 2.583 | 5.006 |

| 4715 | 59 | 8.2 | 5 | 54.319995 110.993898 | 204 | 25 | 204 | 3.757 | 22.915 |

| 4718 | 42 | 9.0 | 20 | 53.44499 110.11831 | 118 | 4 | 118 | 1.929 | 4.601 |

| 4719 | 48 | 9.0 | 20 | 53.444944 110.118236 | 139 | 15 | 139 | 2.857 | 8.205 |

| 4721 | 50 | 9.0 | −80 | 53.444934 110.118312 | 253 | 12 | 253 | 4.123 | 26.826 |

| 4722 | 59 | 9.0 | −40 | 53.444934 110.118312 | 79 | 15 | 79 | 2.966 | 11.746 |

| 4723 | 59 | 8.8 | −50 | 53.444934 110.118312 | 85 | 10 | 85 | 1.873 | 2.626 |

| 4724 | 58 | 9.0 | 10 | 53.445062 110.118303 | 39 | 11 | 39 | 1.710 | 2.975 |

| 4725 | 50 | 9.0 | −200 | 53.444934 110.118312 | 277 | 18 | 277 | 4.286 | 37.994 |

| 4728 | 53 | 8.3 | 55 | 53.414930 109.354914 | 211 | 24 | 211 | 3.790 | 15.816 |

| 4730 | 51 | 9.1 | −115 | 53.414989 109.354720 | 227 | 17 | 227 | 3.734 | 17.388 |

| 4731 | 52 | 9.1 | −115 | 52.987259 108.30778 | 125 | 17 | 125 | 3.166 | 12.368 |

| 4732 | 45 | 7.2 | 10 | 52.987238 108.307715 | 231 | 12 | 231 | 3.593 | 15.933 |

| 4733 | 48 | 9.0 | −170 | 52.987238 108.307715 | 389 | 18 | 389 | 4.480 | 33.697 |

| 4734 | 48 | 9.0 | −300 | 52.987188 108.307606 | 72 | 6 | 72 | 1.575 | 2.331 |

| 4735 | 48 | 7.9 | −160 | 52.987188 108.307606 | 515 | 22 | 515 | 5.194 | 76.778 |

| 4736 | 41 | 9.3 | −350 | 53.766396 109.027353 | 176 | 12 | 176 | 2.838 | 6.318 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maltseva, A.I.; Elcheninov, A.G.; Klyukina, A.A.; Gololobova, A.V.; Lavrentyeva, E.V.; Banzaraktsaeva, T.G.; Dambaev, V.B.; Barkhutova, D.D.; Zavarzina, D.G.; Frolov, E.N. Microbial Diversity of the Baikal Rift Zone Freshwater Alkaline Hot Springs and the Ecology of Polyextremophilic Dissimilatory Iron-Reducing Bacteria. Biology 2025, 14, 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121716

Maltseva AI, Elcheninov AG, Klyukina AA, Gololobova AV, Lavrentyeva EV, Banzaraktsaeva TG, Dambaev VB, Barkhutova DD, Zavarzina DG, Frolov EN. Microbial Diversity of the Baikal Rift Zone Freshwater Alkaline Hot Springs and the Ecology of Polyextremophilic Dissimilatory Iron-Reducing Bacteria. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121716

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaltseva, Anastasia I., Alexander G. Elcheninov, Alexandra A. Klyukina, Alexandra V. Gololobova, Elena V. Lavrentyeva, Tuyana G. Banzaraktsaeva, Vyacheslav B. Dambaev, Darima D. Barkhutova, Daria G. Zavarzina, and Evgenii N. Frolov. 2025. "Microbial Diversity of the Baikal Rift Zone Freshwater Alkaline Hot Springs and the Ecology of Polyextremophilic Dissimilatory Iron-Reducing Bacteria" Biology 14, no. 12: 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121716

APA StyleMaltseva, A. I., Elcheninov, A. G., Klyukina, A. A., Gololobova, A. V., Lavrentyeva, E. V., Banzaraktsaeva, T. G., Dambaev, V. B., Barkhutova, D. D., Zavarzina, D. G., & Frolov, E. N. (2025). Microbial Diversity of the Baikal Rift Zone Freshwater Alkaline Hot Springs and the Ecology of Polyextremophilic Dissimilatory Iron-Reducing Bacteria. Biology, 14(12), 1716. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121716