Hyperspectral Imaging and Machine Learning for Automated Pest Identification in Cereal Crops

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

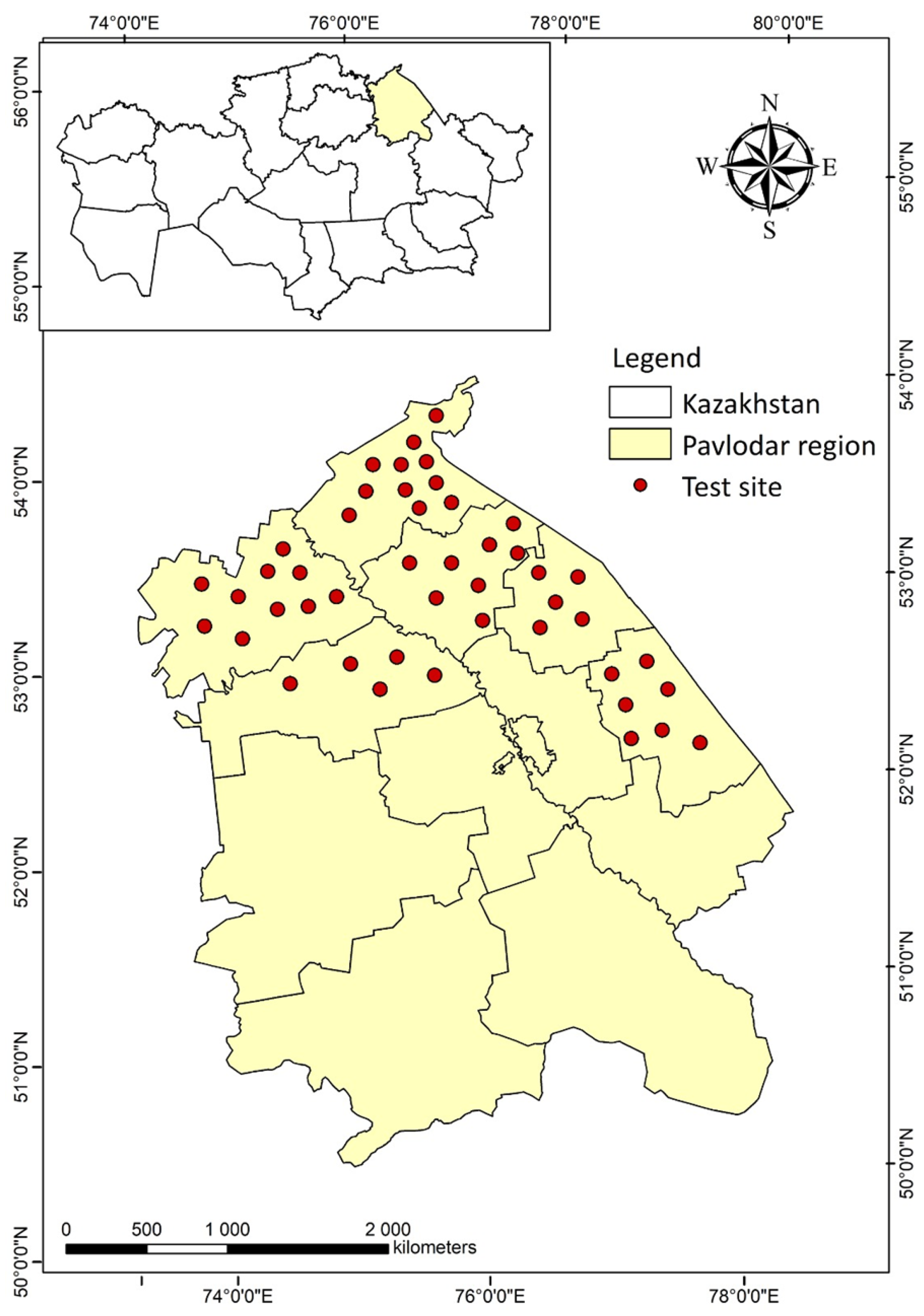

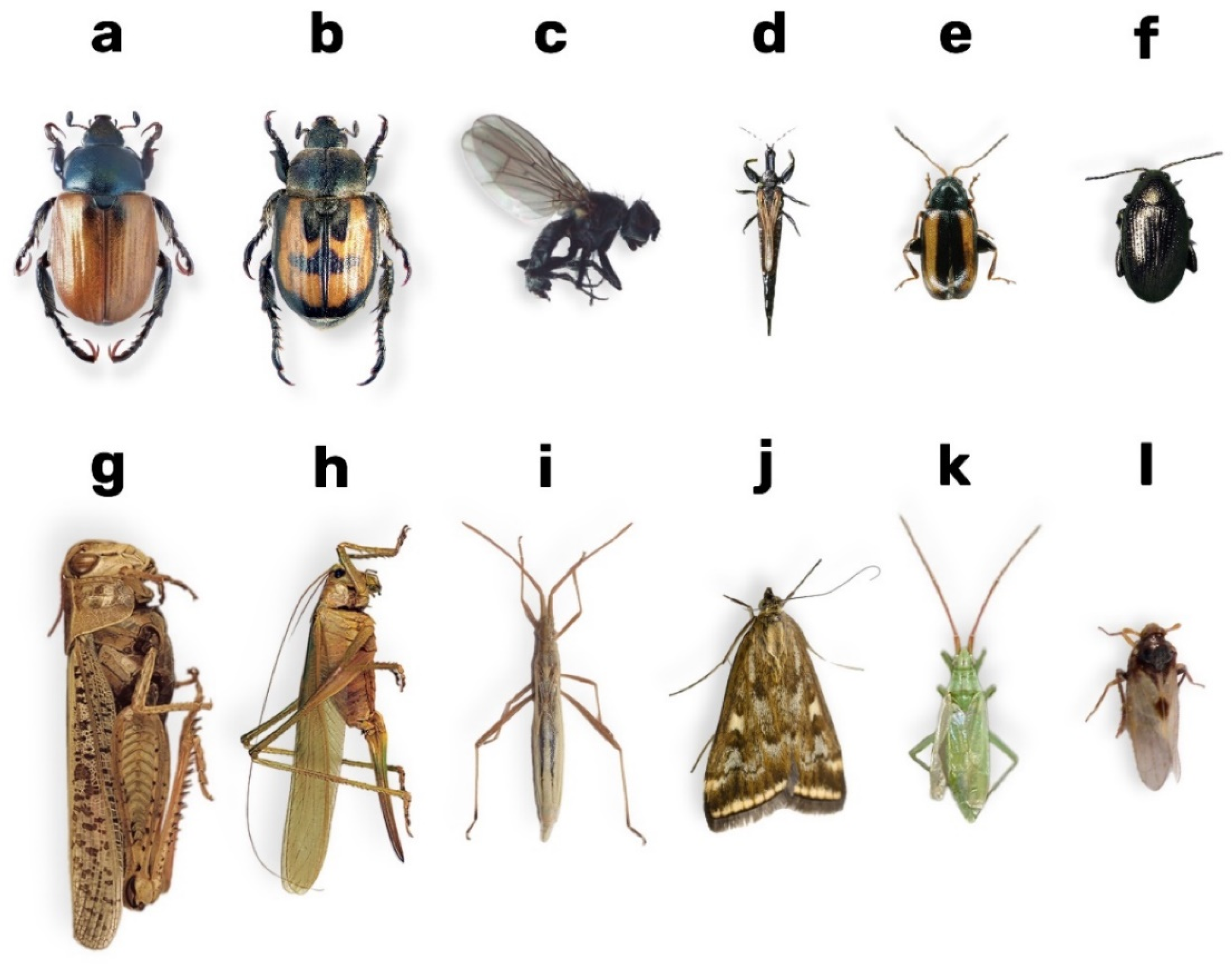

2.1. Research Objects and Test Sites

2.2. Collection and Taxonomic Identification of Entomological Material

2.3. Hyperspectral Imaging

2.3.1. Sample Preparation for Hyperspectral Imaging

2.3.2. Hyperspectral Imaging and Image Processing

Technical Parameters and Imaging Mode

Image Processing and Preparation for Classification

2.3.3. Interactive Spectral Analysis Using PCA and Pixel Explore

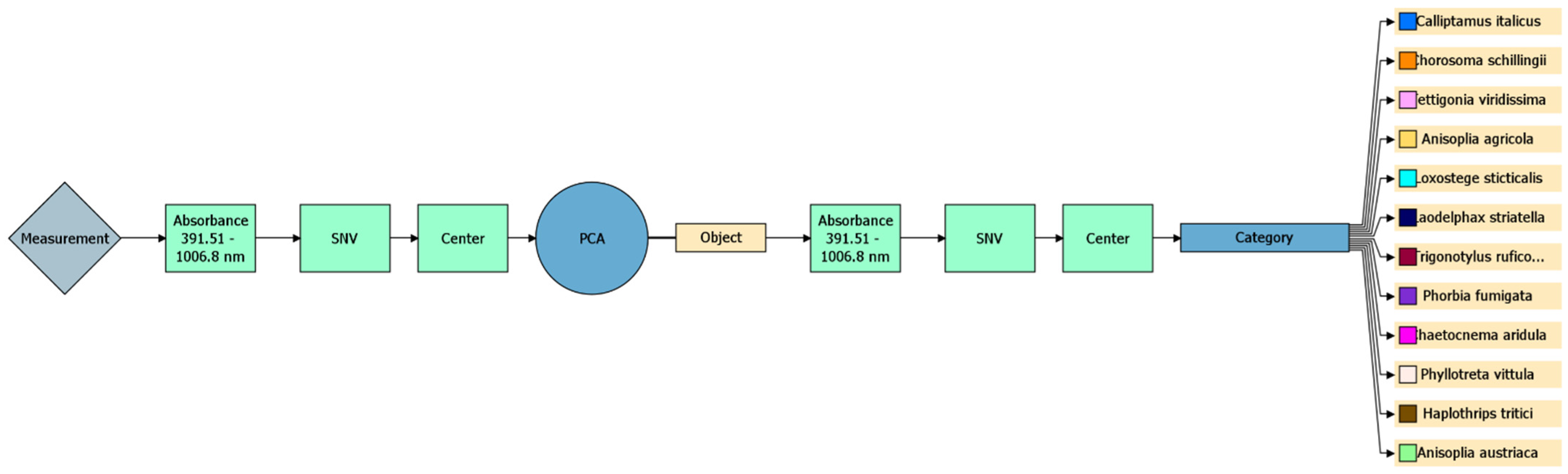

2.3.4. Machine Learning for Identifying and Differentiating Pest Species

- -

- PCA (Principal Component Analysis)—to reduce the number of spectral variables while keeping the most important differences;

- -

- PLS-DA (Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis)—to classify samples based on spectral data;

- -

- SVM (Support Vector Machine) with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel and default parameter settings for C and γ, as implemented in Breeze, was used to perform both binary and multi-class classification tasks [33].

2.4. Statistical Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Spectral Characteristics of Insect Morphological Structures and Integuments Based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3.1.1. Anisoplia austriaca and Anisoplia agricola

3.1.2. Phorbia fumigata

- (1)

- In the visible spectrum (400–700 nm), reflectance is relatively low (10–50%) (10–50%), which corresponds to the dark (below 50%), light-absorbing colouration of the insect’s body;

- (2)

3.1.3. Calliptamus italicus

3.1.4. Loxostege sticticalis

3.1.5. Haplothrips tritici

3.1.6. Phyllotreta vittula

3.1.7. Chaetocnema aridula

3.1.8. Tettigonia viridissima

3.1.9. Trigonotylus ruficornis

3.1.10. Chorosoma schillingi

3.1.11. Laodelphax striatella

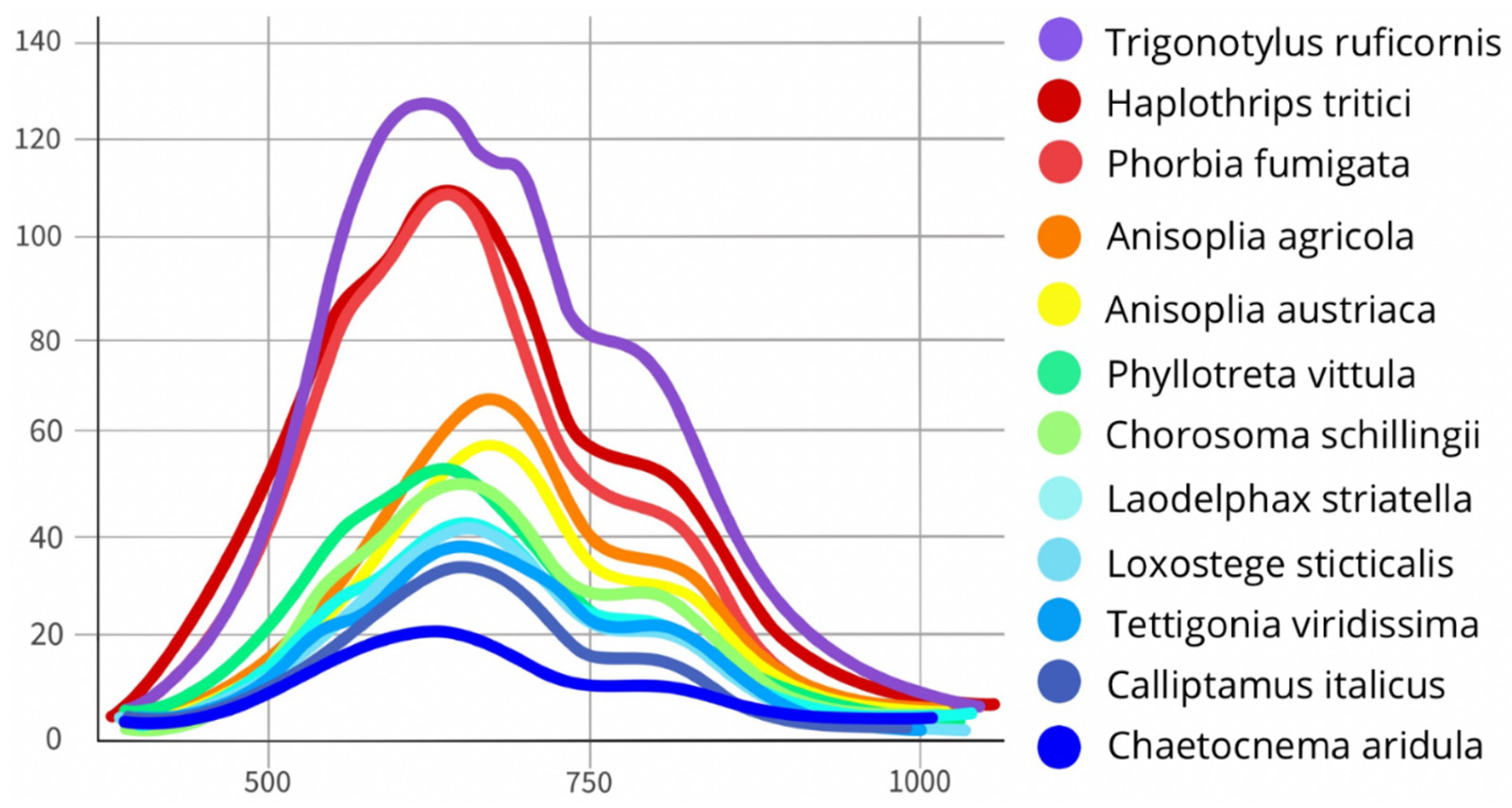

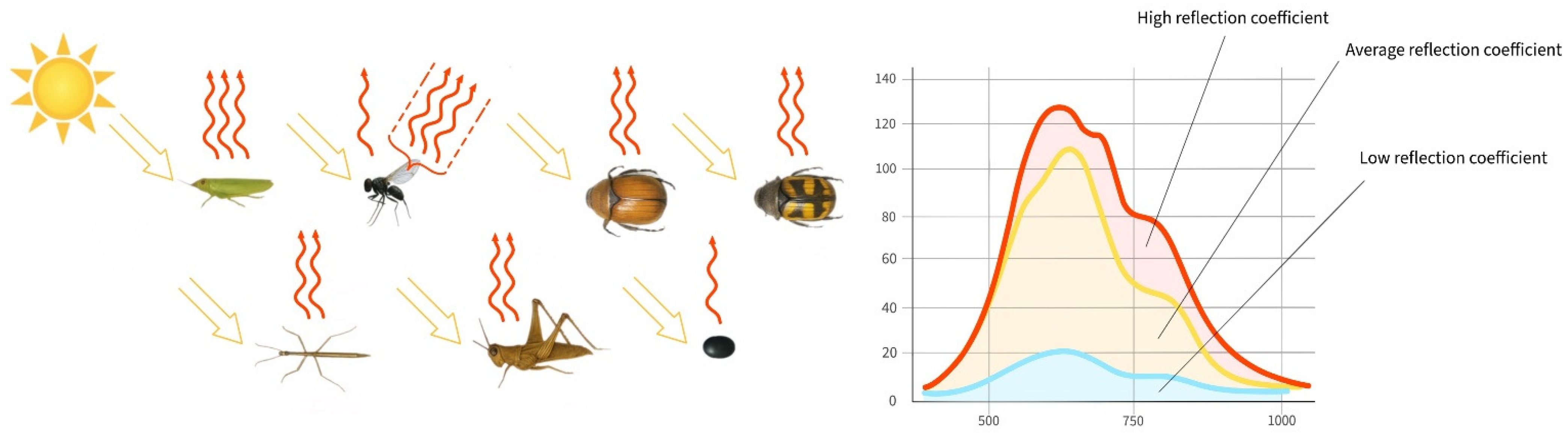

3.2. Differentiation of Agrocenosis Objects by Hyperspectral Characteristics

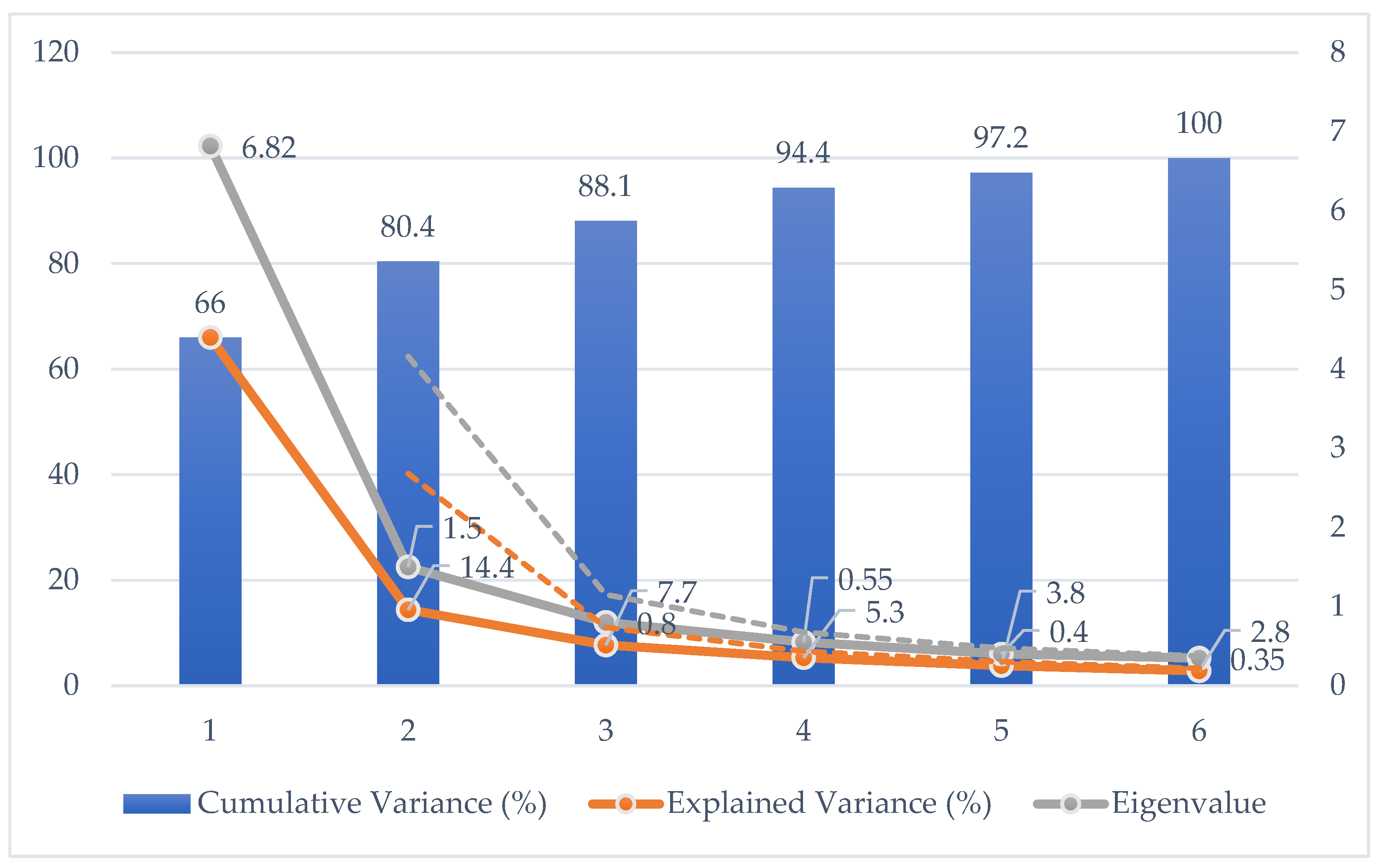

3.3. Statistical Analysis of Insect Spectral Characteristics Using Multivariate Methods

3.4. Species Identification of Pest Entomofauna from Hyperspectral Data Using a PLS-DA Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretative Analysis of the Identified Spectral Characteristics of Insects

4.1.1. Dependence of Spectral Signatures on the Pigment Composition of Insects

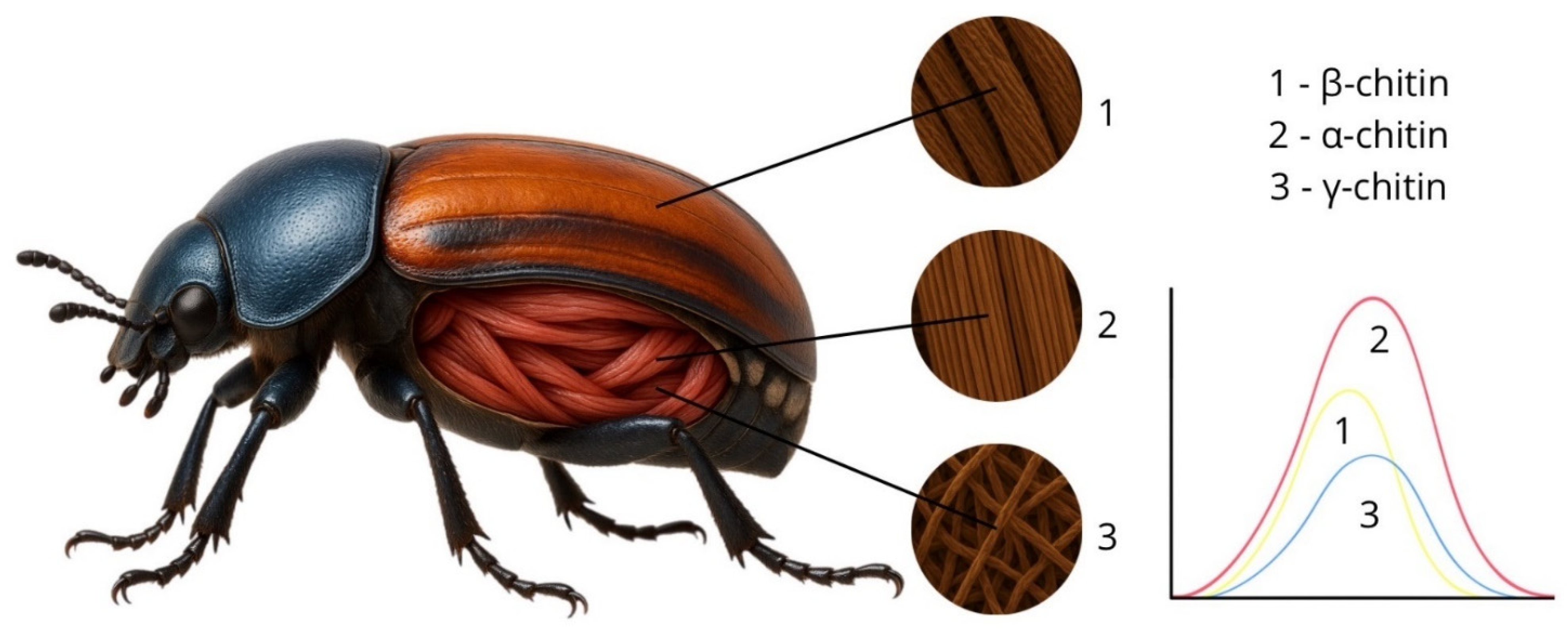

4.1.2. Influence of Exoskeleton Structure on the Spectral Characteristics of Insects

4.1.3. Spectral Reflectance of Insect Body Parts

4.2. Interpretive Analysis of PLS-DA Model Performance in the Context of Insect Spectral Variability and Morphometrics

4.3. Practical Significance of the Study

4.4. Economic Efficiency

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Palmquist, J. Detecting Defects on Cheese Using Hyperspectral Image Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Umeå University, Umea, Sweden, 2020; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Sajib, M.M.H.; Sayem, A.S.M. Innovations in Sensor-Based Systems and Sustainable Energy Solutions for Smart Agriculture: A Review. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgrebe, D.A.; Serpico, S.B.; Crawford, M.M.; Singhroy, V. Introduction to the special issue on analysis of hyperspectral image data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 1343–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, M.; Zemanek, T.; Wuttke, D.; Dinkel, M.; Serfling, A.; Böckmann, E. Hyperspectral imaging for pest symptom detection in bell pepper. Plant Methods 2024, 20, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, M.Y.; Spohr, L.J.; Barchia, I.; Goodwin, S. Rapid estimation of numbers of whiteflies (Hemiptera: Aleurodidae) and thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on sticky traps. Aust. J. Entomol. 1999, 38, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, X.; Lei, J. High-quality spectral-spatial reconstruction using saliency detection and deep feature enhancement. Pattern Recognit. 2019, 88, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabalka, Y.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Chanussot, J. Spectral–spatial classification of hyperspectral imagery based on partitional clustering techniques. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 2973–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Forero, S.; Manian, V. Improving hyperspectral image classification using spatial preprocessing. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2009, 6, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, R.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, J. Hyperspectral Imaging and Their Applications in the Nondestructive Quality Assessment of Fruits and Vegetables. In Hyperspectral Imaging in Agriculture, Food and Environment; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Yang, N.; Sun, Z. Advances in Hyperspectral and Diffraction Imaging for Agricultural Applications. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Guo, Z.; Fernandes Barbin, D.; Dai, Z.; Watson, N.; Povey, M.; Zou, X. Hyperspectral Imaging and Deep Learning for Quality and Safety Inspection of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 10019–10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.-I. Hyperspectral Imaging: Techniques for Spectral Detection and Classification; Kluwer: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirik, M. Hyperspectral Spectrometry as a Means to Differentiate Uninfested and Infested Winter Wheat by Greenbug (Hemiptera: Aphididae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2006, 99, 1682–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansy, D.L.; Murali, M. UAV hyperspectral remote sensor images for mango plant disease and pest identification using MD-FCM and XCS-RBFNN. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Kuska, M.T.; Bohnenkamp, D.; Brugger, A.; Alisaac, E.; Wahabzada, M.; Behmann, J.; Mahlein, A.K. Benefits of hyperspectral imaging for plant disease detection and plant protection: A technical perspective. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2018, 125, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Liu, J.; Zhao, C.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yu, H.; Xu, B.; Yang, X.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, X.; et al. Unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing for field-based crop phenotyping: Current status and perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, D.; Manickavasagan, A. Machine learning techniques for analysis of hyperspectral images to determine quality of food products: A review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignati, S.; Tugnolo, A.; Giovenzana, V.; Pampuri, A.; Casson, A.; Guidetti, R.; Beghi, R. Hyperspectral imaging for fresh-cut fruit and vegetable quality assessment: Basic concepts and applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.T.; Monjur, O.; Khaliduzzaman, A.; Kamruzzaman, M. A comprehensive review of deep learning-based hyperspectral image reconstruction for agri-food quality appraisal. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Dixit, Y.; Reis, M.M.; Brightwell, G. Hyperspectral imaging and machine learning in food microbiology: Developments and challenges in detection of bacterial, fungal, and viral contaminants. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3717–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajri, D.M.N.; Mahmudy, W.F.; Yulianti, T. Detection of disease and pest of kenaf plant using convolutional neural network. J. Inf. Technol. Comput. Sci. 2021, 6, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, Y.; Parab, J.S.; Naik, G.M. Back-Propagation Neural Network (BP-NN) model for the detection of borer pest attack. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1921, 012079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillas, J.E.; Zoilo, F.; Pequero, R.; Jayoma, J.; Daguil, R. Design and development of a stationary pest infestation monitoring device for rice insect pests using convolutional neural network and raspberry pi. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 635–638. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, T. Research on edge detection of agricultural pest and disease leaf image based on LvQ neural network. Recent Adv. Comput. Sci. Commun. 2021, 14, 1903–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, G.; Shrivastava, V.K.; Parvathi, K. Tomato pest classification using deep convolutional neural network with transfer learning, fine tuning and scratch learning. Intell. Decis. Technol. 2021, 15, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejasree, G.; Agilandeeswari, L. An extensive review of hyperspectral image classification and prediction: Techniques and challenges. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 80941–81038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacotte, V.; Dell’Aglio, E.; Peignier, S.; Benzaoui, F.; Heddi, A.; Rebollo, R.; Silva, P. A comparative study revealed hyperspectral imaging as a potential standardized tool for the analysis of cuticle tanning over insect development. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nansen, C.; Elliott, N. Remote Sensing and Reflectance Profiling in Entomology. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2016, 61, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.J.; Khan, H.S.; Yousaf, A.; Khurshid, K.; Abbas, A. Modern trends in hyperspectral image analysis: A review. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 14118–14129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Li, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-Y.; Huang, Y.-M. An AIoT based smart agricultural system for pests detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 180750–180761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, S.; Garg, P.K. A review on computer vision-based techniques for pest detection and monitoring in agriculture. J. Imaging 2021, 7, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Huang, H.; Du, Q.; Zhang, M. Hyperspectral imaging for insect detection and classification: A review on kernel-based methods. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2094. [Google Scholar]

- Peignier, S.; Lacotte, V.; Duport, M.-G.; Baa-Puyoulet, P.; Simon, J.-C.; Calevro, F.; Heddi, A.; da Silva, P. Detection of aphids on hyperspectral images using one-class svm and laplacian of gaussians. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatasaichandrakanth, P.; Iyapparaja, M. Review on Pest Detection and Classification in Agricultural Environments Using Image-Based Deep Learning Models and Its Challenges. Opt. Mem. Neural Netw. 2023, 32, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Thiesen, L.V.; Iost Filho, F.H.; Yamamoto, P.T. Hyperspectral imaging and machine learning: A promising tool for the early detection of Tetranychus urticae Koch infestation in cotton agriculture. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, M.; Prasad, Y.; Vennila, S.; Thirupathi, M.; Sreedevi, G.; Rao, G.R.; Venkateswarlu, B. Hyperspectral indices for assessing damage by the solenopsis mealybug (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) in cotton. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 97, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nansen, C.; Zhang, Y. Integrative insect taxonomy based on morphology, mitochondrial DNA, and hyperspectral reflectance profiling. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 177, 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, V.; Calvini, R.; Boom, B.; Menozzi, C.; Rangarajan, A.K.; Maistrello, L.; Offermans, P.; Ulrici, A. Evaluation of the potential of near-infrared hyperspectral imaging for monitoring the invasive brown marmorated stink bug. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2023, 234, 104751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, G.C.; Silva, N.C. Images in red: A methodological and integrative approach for the usage of Near-infrared Hyperspectral Imaging (NIR-HSI) on collection specimens of Orthoptera (Insecta). bioXiv 2024, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.; Duan, Z.; Lian, M.; Zhao, G.Y.; Sun, X.H.; Hu, J.D.; Gao, L.N.; Feng, H.Q.; Svanberg, S. Optical characterization of agricultural pest insects: A methodological study in the spectral and time domains. Appl. Phys. B 2016, 122, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Di, M.; Hu, T. Visible-NIR Hyperspectral Imaging Based on Characteristic Spectral Distillation Used for Species Identification of Similar Crickets. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 183, 112420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, P.; Hacken, M.; Meijden, A.; Snik, F.; De Dood, M.J. Polarization resolved hyperspectral imaging of the beetle Protaetia speciosa jousselini. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 14858–14871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, J.; Tripathy, S. Role of Micro-Architectures on Insects’ Elytra Affects the Nanomechanical and Optical Properties: Inspired for Designing the Lightweight Materials. J. Opt. Photonics Res. 2024, 1, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielewczik, M.; Liebisch, F.; Walter, A.; Greven, H. Near-infrared (NIR)-reflectance in insects–Phenetic studies of 181 species. Entomol. Heute 2012, 24, 183–215. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Yang, L.; Meng, L.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Fu, X.; Du, X.; Wu, D. Potential of Visible and Near-Infrared Hyperspectral Imaging for Detection of Diaphania pyloalis Larvae and Damage on Mulberry Leaves. Sensors 2018, 18, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajith, S.; Vijayakumar, S.; Elakkiya, N. Yield prediction, pest and disease diagnosis, soil fertility mapping, precision irrigation scheduling, and food quality assessment using machine learning and deep learning algorithms. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithambarathanu, M.; Jeyakumar, M.K. Survey on crop pest detection using deep learning and machine learning approaches. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 42277–42310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlando, V.S.W.; Galo, M.d.L.B.T.; Martins, G.D.; Lingua, A.M.; de Assis, G.A.; Belcore, E. Hyperspectral Characterization of Coffee Leaf Miner (Leucoptera coffeella) (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae) Infestation Levels: A Detailed Analysis. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Jiang, S.; Huang, X.; Zhang, L.; Gan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhou, C. Detection of Rice Leaf Folder in Paddy Fields Based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Based Hyperspectral Images. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskvichev, A.Y. Phytosanitary Control of Plants: A Textbook; Volgograd State Agricultural University: Volgograd, Russia, 2015; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev, G.S. Keys to the Insects of the European Part of the USSR; U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 1988; Volume I–V. [Google Scholar]

- Kokaly, R.F.; Skidmore, A.K. Plant phenolics and absorption features in vegetation reflectance spectra near 1.66 μm. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2015, 43, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.; Blanc-Talon, J.; Urschler, M.; Delmas, P. Wavelength and texture feature selection for hyperspectral imaging: A systematic literature review. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 6039–6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina-Rozo, L.; Roberts, A.; Stuart-Fox, D. A generalized approach to characterize optical properties of natural objects. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2022, 137, 534–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolliams, E.; Baribeau, R.; Bialek, A.; Cox, M. Bandwidth correction for generalized bandpass functions. Metrologia 2011, 48, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzalini, A. The skew-normal distribution and related multivariate families. Scand. J. Stat. 2005, 32, 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagelkerke, N.J.D. A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika 1991, 78, 691–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudall, K.M.; Kenchington, W. The chitin system. Biol. Rev. 1973, 48, 597–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabalak, M.; Aracagök, D.; Torun, M. Extraction, characterization and comparison of chitins from large bodied four Coleoptera and Orthoptera species. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, M.; Baran, T.; Asan-Ozusaglam, M.; Cakmak, Y.S.; Tozak, K.O.; Mol, A.; Mentes, A.; Sezen, G. Comparison of chitin structures isolated from seven different insects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 72, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavenga, D. Colour in the eyes of insects. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2002, 188, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthier, S.; Charron, E.; Boulenguez, J. Morphological structure and optical properties of the wings of Morphidae. Insect Sci. 2006, 13, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahimi, D.; Mesli, L.; Rahmouni, A.; Zeggai, F.Z.; Khaldoun, B.; Chebout, R.; Belbachir, M. Why orthoptera fauna resist of pesticide? First experimental data of resistance phenomena. Data Brief 2020, 30, 105659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che’Ya, N.N.; Mohidem, N.A.; Roslin, N.A.; Saberioon, M.; Tarmidi, M.Z.; Arif Shah, J.; Fazlil Ilahi, W.F.; Man, N. Mobile Computing for Pest and Disease Management Using Spectral Signature Analysis: A Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Yin, K.; Geng, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y. Pest identification via hyperspectral image and deep learning. SIViP 2022, 16, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, W.; Li, H. Hyperspectral image reconstruction by deep convolutional neural network for classification. Pattern Recognit. 2017, 63, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Li, J.; Luo, Z.; Chapman, M. Spectral-spatial residual network for hyperspectral image classification: A 3-d deep learning framework. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 56, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Research Object | Insect Category | Impact on Grain Crops | Justification for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anisoplia austriaca | Pest of grain crops | Feeds on grains, damages ears, reduces crop yield | Widespread in cereal fields and of significant economic importance |

| 2 | Anisoplia agricola | Pest of grain crops | Feeds on grains during the grain-filling stage | Economically significant, especially during population outbreaks in dry periods |

| 3 | Phorbia fumigata | Pest of grain crops | Larvae damage the underground part of the stem, causing wilting of young seedlings | A dangerous pest during the early seedling stage |

| 4 | Trigonotylus ruficornis | Pest of grain crops | Sucks sap from stems and leaves, disrupting photosynthesis and plant growth | Significantly reduces grain crop yield |

| 5 | Phyllotreta vittula | Pest of grain crops | Chews on leaves, leading to seedling damage | A serious threat during the early growth stages of crops |

| 6 | Haplothrips tritici | Pest of grain crops | Feeds on grains within ears, reducing their quality and weight | Mass outbreaks cause substantial yield losses |

| 7 | Chorosoma schillingii | Pest of grain crops | Degrades grain quality by extracting sap from ears and stems | Causes “empty-ear” syndrome |

| 8 | Loxostege sticticalis | Polyphagous pest | Causes leaf skeletonisation | Outbreaks can result in complete destruction of crops |

| 9 | Tettigonia viridissima | Polyphagous pest | Damages leaves and stems | Reduces photosynthetic activity by damaging vegetative biomass; high local densities reduce yield |

| 10 | Chaetocnema aridula | Pest of grain crops | Larvae damage roots and stems; adults feed on leaves | Causes both above- and below-ground damage, especially severe during drought conditions |

| 11 | Calliptamus italicus | Polyphagous pest | Consumes aerial parts of plants, including crops | Outbreaks can devastate large crop areas and disrupt structures of agricultural landscapes |

| 12 | Laodelphax striatella | Pest of grain crops | Damages phloem and transmits viruses | Weakens plants through direct feeding and virus transmission, disrupting metabolism and reducing yields |

| Principal Component | Eigenvalue | Explained Variance (%) | Cumulative Variance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 6.82 | 66.0 | 66.0 |

| PC2 | 1.50 | 14.4 | 80.4 |

| PC3 | 0.80 | 7.7 | 88.1 |

| PC4 | 0.55 | 5.3 | 93.4 |

| PC5 | 0.40 | 3.8 | 97.2 |

| PC6 | 0.35 | 2.8 | 100.0 |

| No. | Species | Body Part | Wavelength (nm) | Reflection Coefficient (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phorbia fumigata | Body | 500–780 | 50–120 |

| Head, thorax, abdomen | 500–750 | 45–60 | ||

| Wings | 500–780 | 58–85 | ||

| Compound eyes | 500–750 | 60–70 | ||

| 2 | Trigonotylus ruficornis | Body | 500–800 | 90–110 |

| 3 | Haplothrips tritici | Body | 500–780 | 75–100 |

| 4 | Anisoplia austriaca | Body (top view) | 600–800 | 50–60 |

| Head, scutellum, pronotum | 500–750 | 20 | ||

| Elytra | 600–800 | 60–75 | ||

| Legs | 500–750 | 37.5 | ||

| Body (bottom view) | 500–750 | 35 | ||

| 5 | Anisoplia agricola | Body (top view) | 600–780 | 35–40 |

| Head, scutellum, pronotum | 500–750 | 20 | ||

| Elytra | 600–780 | 40–50 | ||

| Legs | 500–750 | 25 | ||

| Body (bottom view) | 500–750 | 30 | ||

| 6 | Phyllotreta vittula | Body | 500–750 | 30–52.5 |

| 7 | Chorosoma schillingi | Body | 500–780 | 35–45 |

| 8 | Loxostege sticticalis | Body | 500–780 | 20–40 |

| Head | 500–750 | 15 | ||

| Wings | 500–780 | 30–38 | ||

| 9 | Laodelphax striatella | Body | 550–750 | 22.5–37.5 |

| 10 | Calliptamus italicus | Body | 550–750 | 22.5–35 |

| Head | 500–750 | 20–25 | ||

| Legs | 500–750 | 35–40 | ||

| 11 | Tettigonia viridissima | Body | 500–750 | 20–25 |

| 12 | Chaetocnema aridula | Body | 500–750 | 10–20 |

| No. | Pest Species | Reflection Coefficient, % | Wave Range, nm | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ | Mкp | SB | SA | |||||||||

| 1 | Anisoplia austriaca | 50 | 60 | 55 | 2.88 | 5.24 | 55 | 10 | 600 | 800 | 200 | −0.07 |

| 2 | Anisoplia agricola | 35 | 40 | 37.50 | 1.44 | 3.84 | 37.50 | 5 | 600 | 780 | 180 | 0.13 |

| 3 | Phorbia fumigata | 35 | 160 | 80 | 36 | 45.10 | 80 | 125 | 500 | 780 | 280 | 0.68 |

| 4 | Haplothrips tritici | 75 | 100 | 86.25 | 7.21 | 8.36 | 86.25 | 25 | 500 | 780 | 280 | −0.26 |

| 5 | Phyllotreta vittula | 30 | 52.50 | 41.25 | 6.49 | 15.74 | 41.25 | 22.50 | 500 | 750 | 250 | 0 |

| 6 | Trigonotylus ruficornis | 75 | 125 | 98.75 | 14.40 | 14.61 | 98.75 | 50 | 500 | 800 | 300 | 0.77 |

| 7 | Chaetocnema aridula | 10 | 20 | 15 | 2.88 | 19.24 | 15 | 10 | 500 | 750 | 250 | 0 |

| 8 | Tettigonia viridissima | 20 | 25 | 18.40 | 1.44 | 7.84 | 18.40 | 5 | 500 | 750 | 250 | 0 |

| 9 | Chorosoma schillingi | 35 | 45 | 32.40 | 2.88 | 8.90 | 32.40 | 10 | 500 | 750 | 250 | 0.39 |

| 10 | Loxostege sticticalis | 20 | 40 | 30 | 5.77 | 19.20 | 30 | 20 | 500 | 780 | 280 | 0 |

| 11 | Calliptamus italicus | 22.50 | 35 | 26.50 | 3.60 | 13.60 | 26.50 | 12.50 | 550 | 750 | 200 | 0.40 |

| 12 | Laodelphax striatella | 22.50 | 37.50 | 33 | 4.33 | 13.12 | 33 | 15 | 550 | 750 | 200 | 0.61 |

| No. | Pest Species | R2 (Coefficient of Determination) | Q2 (Predictive Power of the Model) | RMSEC (Expected Calibration Error) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anisoplia austriaca | 0.912 | 0.898 | 0.041 |

| 2 | Anisoplia agricola | 0.901 | 0.895 | 0.038 |

| 3 | Phorbia fumigata | 0.875 | 0.852 | 0.053 |

| 4 | Haplothrips tritici | 0.799 | 0.778 | 0.076 |

| 5 | Phyllotreta vittula | 0.841 | 0.815 | 0.065 |

| 6 | Trigonotylus ruficornis | 0.854 | 0.831 | 0.061 |

| 7 | Chaetocnema aridula | 0.785 | 0.761 | 0.082 |

| 8 | Tettigonia viridissima | 0.899 | 0.887 | 0.039 |

| 9 | Chorosoma schillingi | 0.855 | 0.833 | 0.069 |

| 10 | Loxostege sticticalis | 0.865 | 0.844 | 0.056 |

| 11 | Calliptamus italicus | 0.888 | 0.876 | 0.045 |

| 12 | Laodelphax striatella | 0.812 | 0.795 | 0.071 |

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Average grain yield | 15.2 | quintal/ha |

| Average cost per quintal of grain | 14.5 | USD |

| Gross revenue per hectare | 220.4 | USD/ha |

| Cost of insecticides | 100,000 | USD/year |

| Insecticide cost per hectare | 7.2 | USD/ha |

| Basic equipment and software cost | 100,000 | USD |

| Personnel and data processing | 40,000 | USD |

| Preparation and operation of environment | 220,000 | USD |

| Additional costs (amortisation, taxes, maintenance, etc.) | 50,000 | USD |

| Total implementation cost | 410,000 | USD |

| Expected reduction in yield losses | 10 | % |

| Expected reduction in insecticide use | 10 | % |

| Total economic benefit per hectare | 23 | USD/ha |

| Break-even area | 17,826 | ha |

| Return on investment (ROI) | 1.0 | ratio |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ualiyeva, R.M.; Kaverina, M.M.; Osipova, A.V.; Faurat, A.A.; Zhangazin, S.B.; Iksat, N.N. Hyperspectral Imaging and Machine Learning for Automated Pest Identification in Cereal Crops. Biology 2025, 14, 1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121715

Ualiyeva RM, Kaverina MM, Osipova AV, Faurat AA, Zhangazin SB, Iksat NN. Hyperspectral Imaging and Machine Learning for Automated Pest Identification in Cereal Crops. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121715

Chicago/Turabian StyleUaliyeva, Rimma M., Mariya M. Kaverina, Anastasiya V. Osipova, Alina A. Faurat, Sayan B. Zhangazin, and Nurgul N. Iksat. 2025. "Hyperspectral Imaging and Machine Learning for Automated Pest Identification in Cereal Crops" Biology 14, no. 12: 1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121715

APA StyleUaliyeva, R. M., Kaverina, M. M., Osipova, A. V., Faurat, A. A., Zhangazin, S. B., & Iksat, N. N. (2025). Hyperspectral Imaging and Machine Learning for Automated Pest Identification in Cereal Crops. Biology, 14(12), 1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121715