Multi-Organ Toxicity of Combined PFOS/PS Exposure and Its Application in Network Toxicology

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Treatment

2.2. Histology Observation of Tissues

2.3. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities and Content

2.4. Toxicity Prediction Analysis

2.5. Acquisition of PFOS/PS and Liver Injury-Related Target Genes

2.6. Construction of the Protein–Protein Interaction

2.7. Core Target Screening

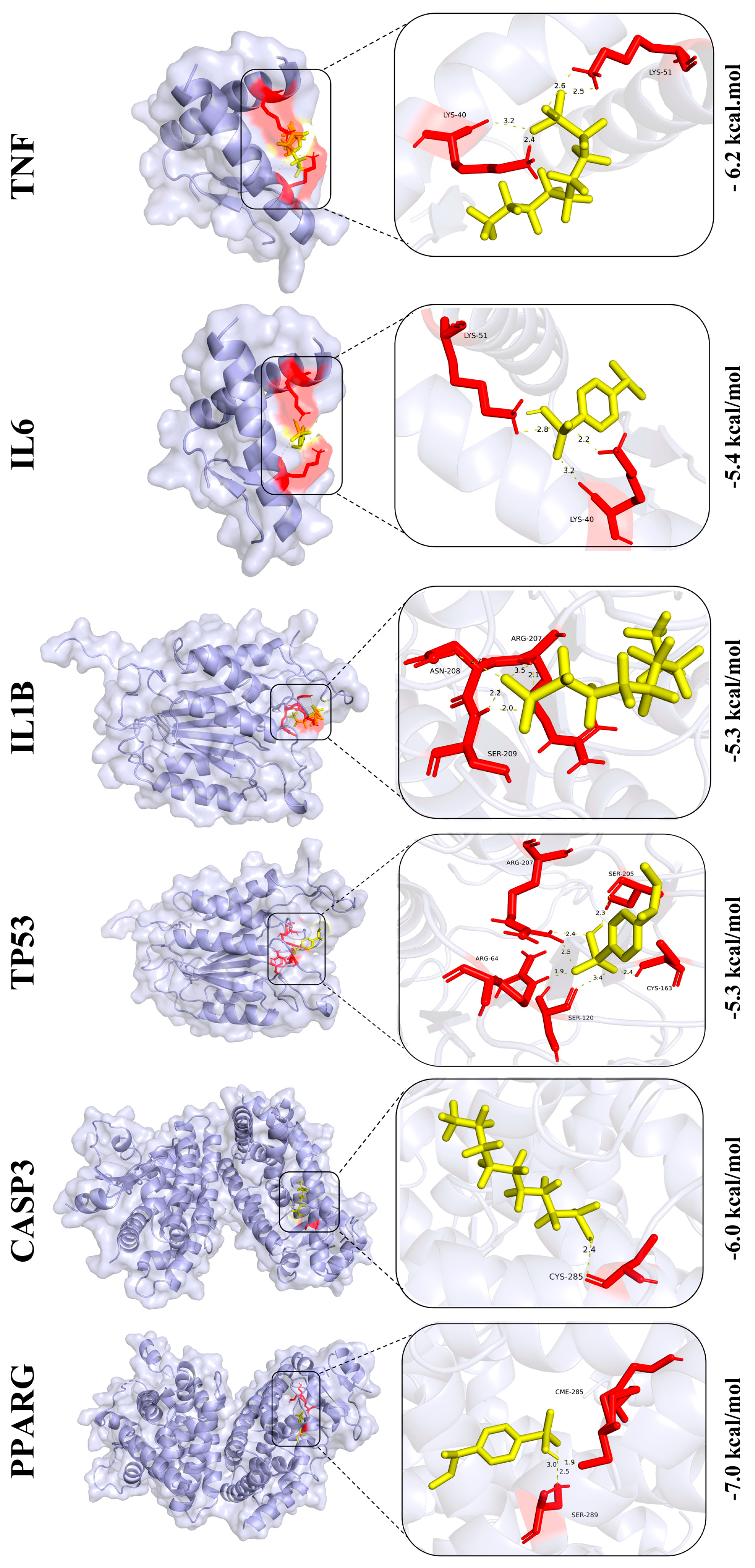

2.8. Molecular Docking

2.9. Integrated Network Toxicology

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Histomorphological Results of Organs During Exposure to PFOS and PS

3.2. Results of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Content in Tissues

3.3. Physical/Chemical Properties and Toxicity Prediction of PFOS and PS

3.4. Target Prediction of PFOS and PS

3.5. Prediction of Liver Injury Disease Targets

3.6. Prediction of Overlapping Targets Between PFOS/PS and Liver Injury

3.7. Genetic Network Analysis of Toxic Components

3.8. Screening and Prediction of Interactions Between Core Regulatory Proteins

3.9. Prediction of Core Protein Interaction Potential for PFOS and PS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, S.; Wang, X.; Kaal, J.; Zhu, S.; Lv, J.; Yin, Y.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Li, D.; Yu, D.; et al. Elevation-dependent soil organic matter persistence and molecular traits influence mercury storage in timberline ecotones. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 499, 140155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Roh, H.S.; Park, Y.J.; Song, H.H.; Choi, J.; Jung, D.W.; Park, S.J.; Park, H.J.; Park, S.H.; Kim, D.E.; et al. Corrigendum to “A three-dimensional mouse liver organoid platform for assessing EDCs metabolites simulating liver metabolism”. Environ. Int. 2025, 202, 109623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhou, L.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X. An Activable Photosensitizer for Sunshine-Driven Photodynamic Therapy Against Multiple-Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria by Exploiting Macrophage Chemotaxis. Adv. Mater. 2025, 23, e08232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, M.J.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, E.; Son, M.; Lee, S. Chronic PET-Microplastic Exposure: Disruption of Gut-Liver Homeostasis and Risk of Hepatic Steatosis. Adv. Sci. 2025, 22, e12030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuoti, E.; Nguyen, J.; Rantakokko, P.; Huhta, H.; Kiviranta, P.; Räsänen, J.; Palosaari, S.; Lehenkari, P. Adipose tissue deposition and placental transfer of persistent organic pollutants in ewes. Environ. Res. 2025, 21, 123164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourson, M.L.; Green, L.C.; Crouch, E.A.C.; Clewell, H.J.; Colnot, T.; Cox, T.; Dekant, W.; Dell, L.D.; Deyo, J.A.; Gadagbui, B.K.; et al. Estimating safe doses of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS): An international collaboration. Arch. Toxicol. 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Ren, J.; Pei, H.; Wen, R.; Zhang, C.; Sun, X.; Yang, W.; Ma, Y. Integrated multi-omics and machine learning approach reveals the mechanism of nicotinamide alleviating PFOS-induced hepatotoxicity. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 8185–8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Tan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ma, L.; Hou, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, R.; Yin, L.; Pu, Y.; et al. Linking PFOS exposure to chronic kidney disease: A multimodal study integrating epidemiology, network toxicology, and experimental validation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 302, 118770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarczuch, A.; Gogola-Mruk, J.; Kotarska, K.; Polański, Z.; Ptak, A. Mitochondrial activity and steroid secretion in mouse ovarian granulosa cells are suppressed by a PFAS mixture. Toxicology 2025, 512, 154083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.; Wang, N.; Xu, Y.; Su, X.; Deng, Z.; Ruan, Y.; Lin, D.; Chen, Y.; Kuang, Z.; Chen, G.; et al. ATF4 participates in perfluorooctane sulfonate-induced neurotoxicity by regulating ferroptosis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 299, 118303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Yu, J.; Zhuge, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, G. Oxidative stress and Cx43-mediated apoptosis are involved in PFOS-induced nephrotoxicity. Toxicology 2022, 478, 153283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Li, G.; Zhao, D.; Xie, X.; Wei, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, M.; Li, G.; Liu, W.; Sun, J.; et al. Relationship between fine particulate air pollution and ischaemic heart disease morbidity and mortality. Heart 2015, 101, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, Z.; Hania, P.; Suehring, R.; Gilbride, K.; Hamza, R. Impact of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) on secondary sludge microorganisms: Removal, potential toxicity, and their implications on existing wastewater treatment regulations in Canada. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2023, 25, 1604–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lv, D.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Han, W. Human exposure to F-53B in China and the evaluation of its potential toxicity: An overview. Environ. Int. 2022, 161, 107108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Li, T.; He, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, C.; Lu, X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Analysis of Biodistribution and in vivo Toxicity of Varying Sized Polystyrene Micro and Nanoplastics in Mice. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 7617–7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.D.; Chen, C.W.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, H.H.; Lee, J.S.; Lin, C.H. Polystyrene microplastic particles: In vitro pulmonary toxicity assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 385, 121575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Hou, S.; Sun, H. A Simple Method for Quantifying Polycarbonate and Polyethylene Terephthalate Microplastics in Environmental Samples by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2017, 4, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Rehati, P.; Yang, Z.; Cai, Z.; Guo, C.; Li, Y. The potential toxicity of microplastics on human health. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prata, J.C. Airborne microplastics: Consequences to human health? Environ. Pollut. 2018, 234, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhuan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Meng, L.; Fu, X.; Hou, Y. Polystyrene microplastics induced female reproductive toxicity in mice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gu, X.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, T. Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and polystyrene microplastics co-exposure caused oxidative stress to activate NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway aggravated pyroptosis and inflammation in mouse kidney. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, T.; Sun, Q.; Tan, B.; Wei, H.; Qiu, X.; Xu, X.; Gao, H.; Zhang, S. Integration of network toxicology and transcriptomics reveals the novel neurotoxic mechanisms of 2, 2′, 4, 4′-tetrabromodiphenyl ether. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 486, 136999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, T.Y.; Simpson, M.J. Time-dependent biomolecular responses and bioaccumulation of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) in Daphnia magna. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D-Genom. Proteom. 2020, 35, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, L.; Zhu, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, W.; Cao, C.; Yang, Y.; Han, C. Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), a novel environmental pollutant, induces liver injury in mice by activating hepatocyte ferroptosis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 267, 115625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Ding, X.; Tian, M.; Ma, Q.; Xu, D. Impacts of PFOS, PFOA and their alternatives on the gut, intestinal barriers and gut-organ axis. Chemosphere 2024, 361, 142461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liang, S.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Sun, Q. Analyzing the impact of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) on the reproductive system using network toxicology and molecular docking. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhu, X.; Zeng, P.; Hu, L.; Huang, Y.; Guo, X.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lai, L.; Xue, A.; et al. Exposure to PFOA, PFOS, and PFHxS induces Alzheimer’s disease-like neuropathology in cerebral organoids. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 363, 125098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, W.; Liang, P.; Feng, R.; Qiu, T.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Yang, G.; Yao, X. The VDAC1 oligomerization regulated by ATP5B leads to the NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the liver cells under PFOS exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 281, 116647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Tian, M.; Xu, D.; Xie, Y. PFOS and Its Substitute OBS Cause Endothelial Dysfunction to Promote Atherogenesis in ApoE−/− Mice. Environ. Health 2025, 3, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, J.H.; Wang, Q.; Meehan-Atrash, J.; Pang, C.; Rahman, I. Developmental PFOS exposure alters lung inflammation and barrier integrity in juvenile mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2024, 201, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cheng, B.; Wu, W.; Chen, Y.; Dai, J.; Li, Y. Mechanistic insights into PFOS-induced inflammatory bowel disease: A network toxicology and molecular docking study. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 5150–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, E.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Qin, C.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L. Interactions of a PFOS/sodium nitrite mixture in Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis): Impacts on survival, growth, behavior, energy metabolism and hepatopancreas transcriptome. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 289, 110114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, W.; Chan, H.; Peng, J.; Zhu, P.; Li, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Z.; et al. Polystyrene microplastics induce size-dependent multi-organ damage in mice: Insights into gut microbiota and fecal metabolites. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Chen, L. Airborne polystyrene nanoplastics exposure leads to heart failure via ECM-receptor interaction and PI3K/AKT/BCL-2 pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; He, J.; Qu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; et al. Gut Microbiota Participates in Polystyrene Microplastics-Induced Hepatic Injuries by Modulating the Gut-Liver Axis. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 15125–15145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Fan, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, L.; Cheng, G.; Yan, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Qian, Q.; Wang, H. Combined exposure of polystyrene nanoplastics and silver nanoparticles exacerbating hepatotoxicity in zebrafish mediated by ferroptosis pathway through increased silver accumulation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, Y.; Guo, H.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y. Polystyrene microplastics induce hepatotoxicity and disrupt lipid metabolism in the liver organoids. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, K.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, H.; Hou, L.; Guo, T.; Zhao, H.; Xing, M. Polystyrene microplastics promote liver inflammation by inducing the formation of macrophages extracellular traps. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 452, 131236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Xu, P.; Sun, G.; Chen, B.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G. Early-life exposure to polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics disrupts metabolic homeostasis and gut microbiota in juvenile mice with a size-dependent manner. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.L.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.J.; Gowen, A.A. A review of potential human health impacts of micro- and nanoplastics exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, S.; Akbari-Adergani, B.; Shafaroodi, H.; Akbari, N.; Basaran, B.; Sadighara, M.; Sadighara, P. A systematic review on the effect of microplastics on the hypothalamus-pituitary-ovary axis based on animal studies. Toxicol. Lett. 2025, 413, 111745. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jahedi, F.; Frad, N.J.H.; Khaksar, M.A.; Rashidi, P.; Safdari, F.; Mansouri, Z. Nano and microplastics: Unveiling their profound impact on endocrine health. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2025, 35, 865–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thin, Z.S.; Chew, J.; Ong, T.Y.Y.; Ali, R.A.R.; Gew, L.T. Impact of microplastics on the human gut microbiome: A systematic review of microbial composition, diversity, and metabolic disruptions. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Wei, T.; Akhtar, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. Polystyrene nanoplastics induce lipophagy via the AMPK/ULK1 pathway and block lipophagic flux leading to lipid accumulation in hepatocytes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 134878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jin, T.; Wang, L.; Tang, J. Polystyrene micro and nanoplastics attenuated the bioavailability and toxic effects of Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) on soybean (Glycine max) sprouts. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 448, 130911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Mahapatra, A.; Manna, B.; Suman, A.; Ray, S.S.; Singhal, N.; Singh, R.K. Sorption of PFOS onto polystyrene microplastics potentiates synergistic toxic effects during zebrafish embryogenesis and neurodevelopment. Chemosphere 2024, 366, 143462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Gong, M.; Yuan, Z. Exposure to polystyrene microplastics and perfluorooctane sulfonate disrupt the homeostasis of intact planarians and the growth of regenerating planarians. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaopeng, C.; Jin, T. Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) causes aging damage in the liver through the mt-DNA-mediated NLRP3 signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 262, 115121. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Q.; Ma, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y. Multi-Organ Toxicity of Combined PFOS/PS Exposure and Its Application in Network Toxicology. Biology 2025, 14, 1714. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121714

Liu Q, Ma X, Liu J, Liu Y. Multi-Organ Toxicity of Combined PFOS/PS Exposure and Its Application in Network Toxicology. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1714. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121714

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Qi, Xianghui Ma, Jiaming Liu, and Yan Liu. 2025. "Multi-Organ Toxicity of Combined PFOS/PS Exposure and Its Application in Network Toxicology" Biology 14, no. 12: 1714. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121714

APA StyleLiu, Q., Ma, X., Liu, J., & Liu, Y. (2025). Multi-Organ Toxicity of Combined PFOS/PS Exposure and Its Application in Network Toxicology. Biology, 14(12), 1714. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121714