Comprehensive Analysis of Mitochondrial Genomic Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Plant Genus Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) Species

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Source

2.2. Sequencing

2.3. Mitochondrial Genome Assembly and Annotation

2.4. Analysis of Mitochondrial Genome Structural Features

2.5. Codon Usage Bias Analysis of Mitochondrial Protein-Coding Genes

2.6. Analysis of Genetic Variation in the Mitochondrial Genome

2.7. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Mitochondrial Genomes in Ipomoea Species

3.2. Characteristics of Protein-Coding Genes in the Mitochondrial Genomes of the Genus Ipomoea

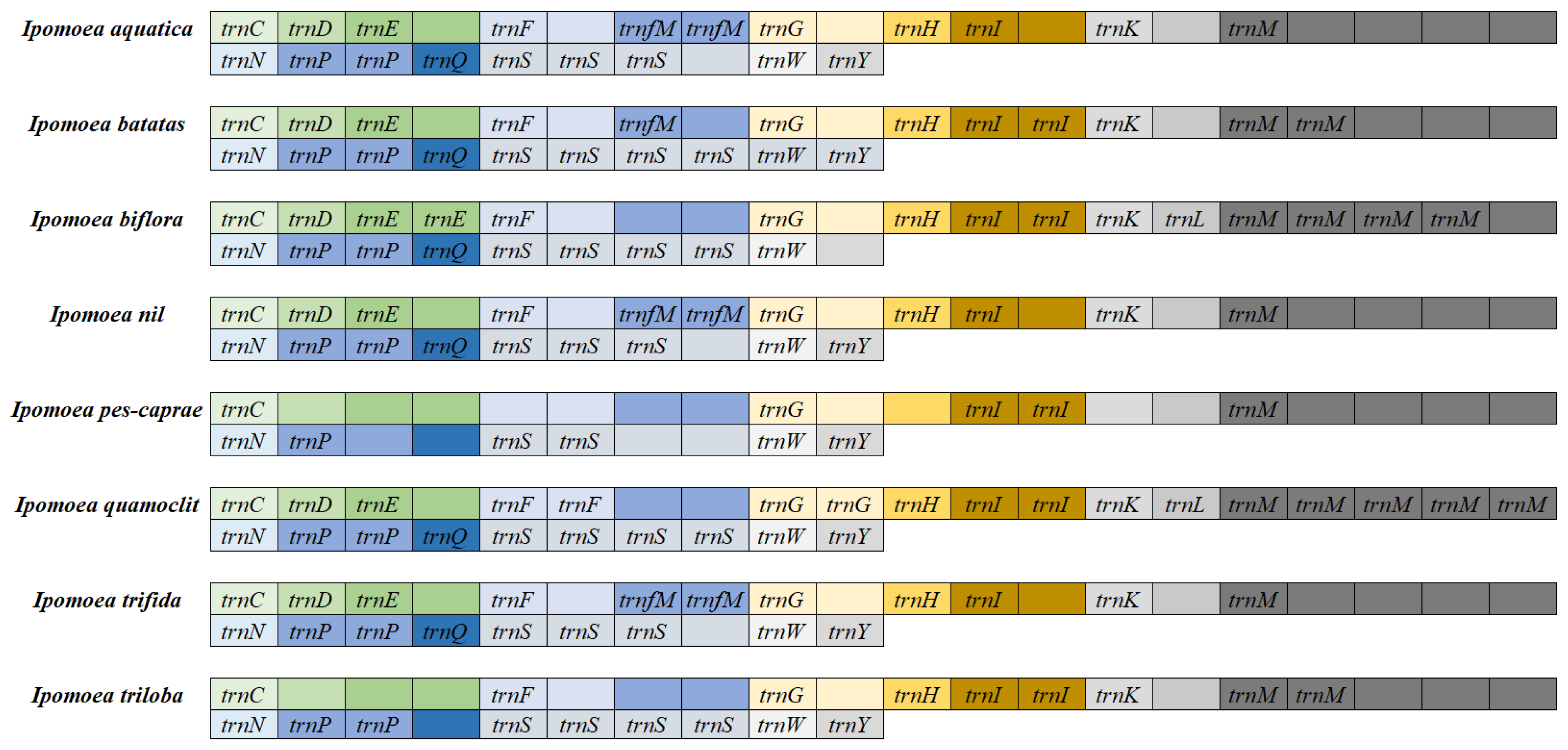

3.3. Analysis of Mitochondrial Genome tRNAs in Ipomoea Species

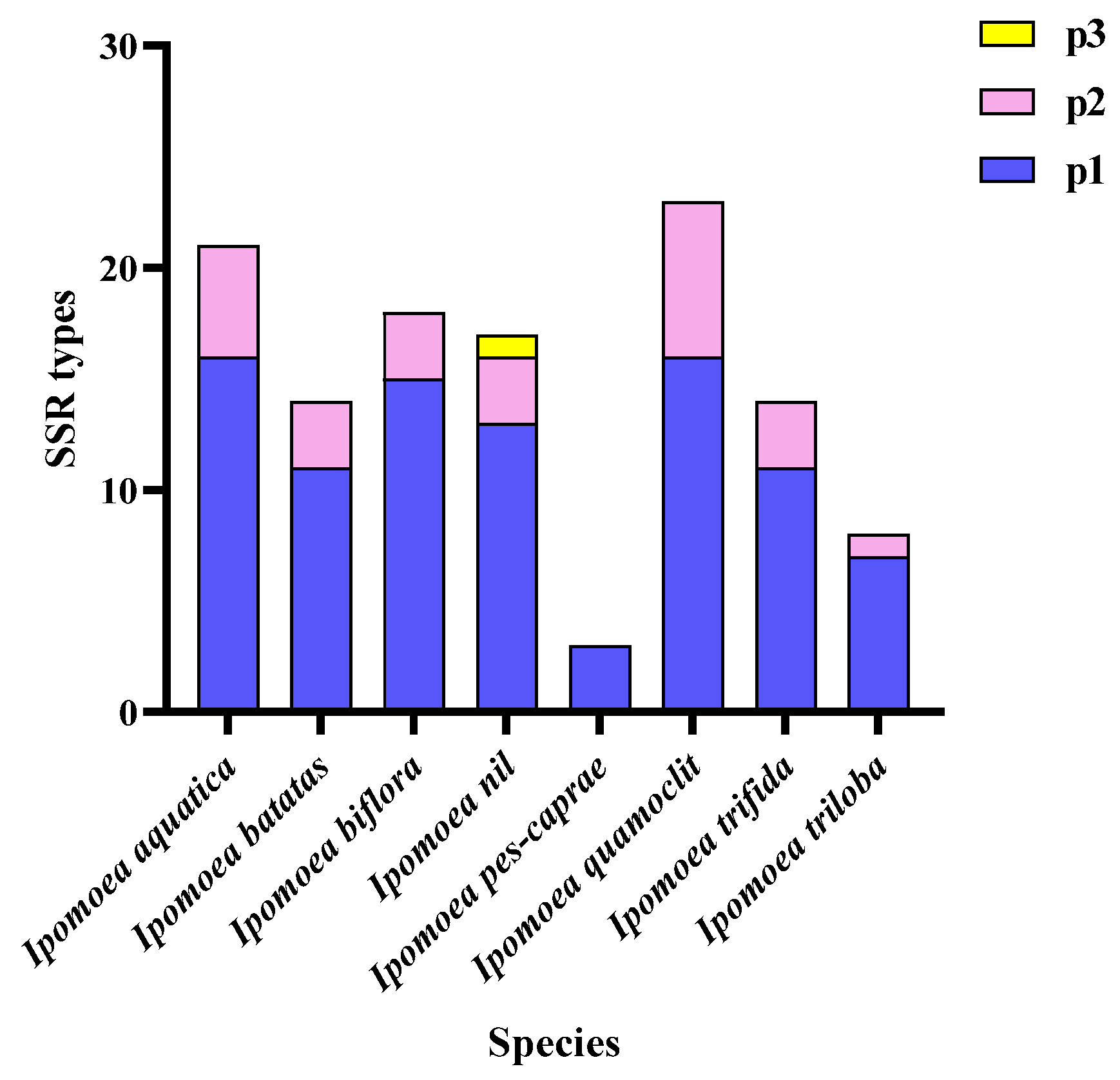

3.4. Analysis of Repetitive Sequences in the Mitochondrial Genomes of the Ipomoea Species

3.5. Genetic Variation Information in Mitochondrial Genomes of Ipomoea Species

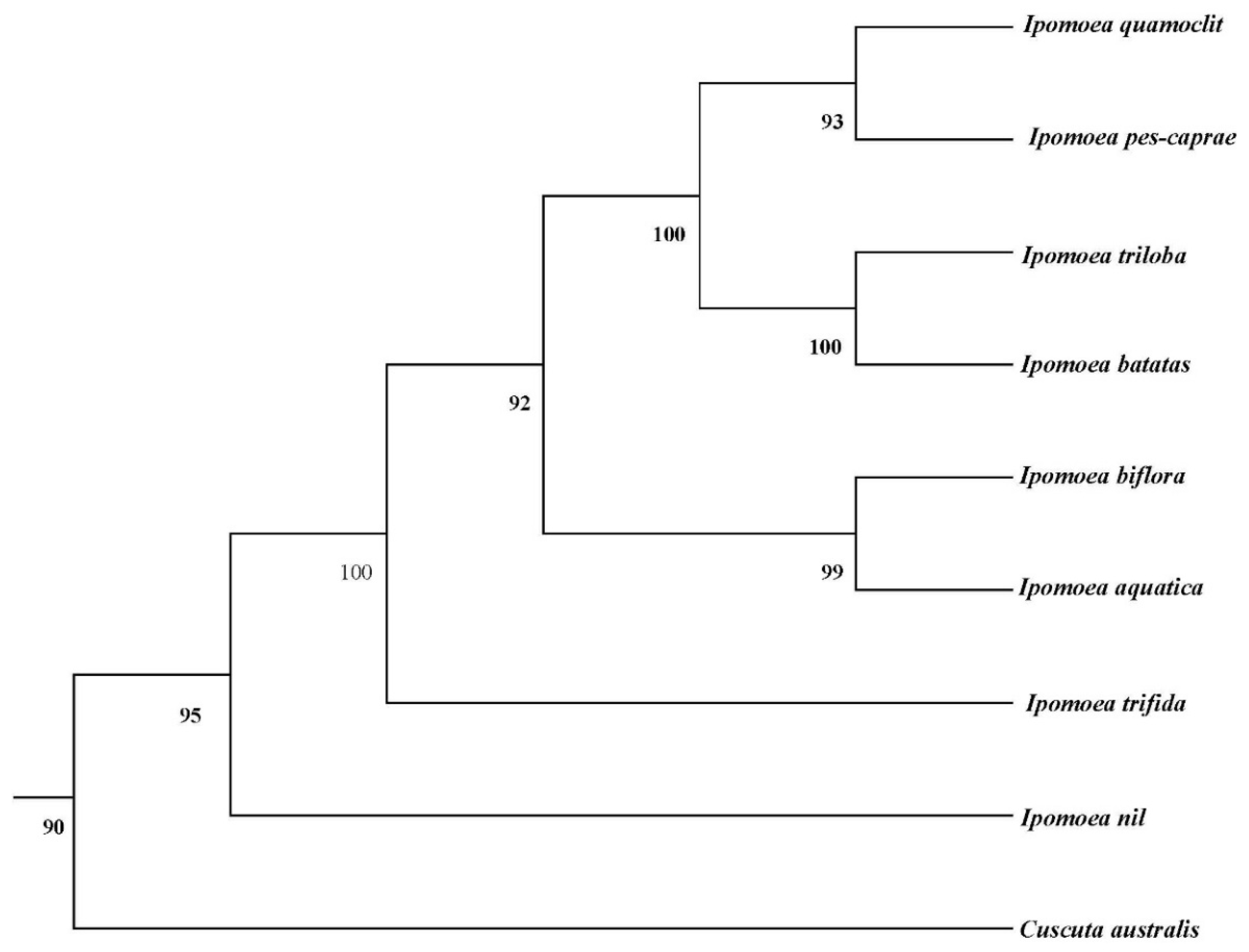

3.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, M.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Moeinzadeh, M.; Quispe-Huamanquispe, D.; Fan, W.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Nie, H. Haplotype-based phylogenetic analysis and population genomics uncover the origin and domestication of sweetpotato. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D. The Ipomoea batatas complex-I. taxonomy. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 1978, 105, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Xu, G.; Li, D.; Clements, D.; Jin, G.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, A.; Zhang, F.; Kato-Noguchi, H. Allelopathic potential of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) germplasm resources of Yunnan Province in southwest China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Clifford, M. Profiling the chlorogenic acids of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) from China. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unseld, M.; Marienfeld, J.; Brandt, P.; Brennicke, A. The mitochondrial genome of Arabidopsis thaliana contains 57 genes in 366,924 nucleotides. Nat. Genet. 1997, 15, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, W.; Kuang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chai, X.; Zhang, Y. The characteristic analysis of 560 plant mitochondrial genome registered in NCBI data. Mol. Plant Breed. 2023, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gualberto, J.; Mileshina, D.; Wallet, C.; Niazi, A.; Weber-Lotfi, F.; Dietrich, A. The plant mitochondrial genome: Dynamics and maintenance. Biochimie 2014, 100, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualberto, J.; Newton, K. Plant mitochondrial genomes: Dynamics and mechanisms of mutation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alverson, A.J.; Wei, X.; Rice, D.W.; Stern, D.B.; Barry, K.; Palmer, J.D. Insights into the evolution of mitochondrial genome size from complete sequences of Citrullus lanatus and Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 1436–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. The Mitochondrial Genome of Cistanche genus in China. Ph.D. Thesis, Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moller, I.M.; Rasmusson, A.G.; Van Aken, O. Plant mitochondria—Past, present and future. Plant J. 2021, 108, 912–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, P.; Quesada, V. Organelle genetics in plants 2.0. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, A.; Peng, R.; Zhuang, J.; Gao, F.; Zhu, B.; Fu, X.; Xue, Y.; Jin, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, W.; et al. Gene duplication and transfer events in plant mitochondria genome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 376, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szandar, K.; Krawczyk, K.; Myszczynski, K.; Slipiko, M.; Sawicki, J.; Szczecinska, M. Breaking the limits-multichromosomal structure of an early eudicot Pulsatilla patens mitogenome reveals extensive RNA-editing, longest repeats and chloroplast derived regions among sequenced land plant mitogenomes. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, S.; Nielsen, B. Plant mitochondrial DNA. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2017, 22, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mower, J. Variation in protein gene and intron content among land plant mitogenomes. Mitochondrion 2020, 53, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mower, J.P.; Sloan, D.B.; Alverson, A.J. Plant Mitochondrial Genome Diversity: The Genomics Revolution; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2012; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Li, X. Analysis of synonymous codon usage patterns in different plant mitochondrial genomes. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2009, 36, 2039–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ling, C.C.; Zhang, H.M.; Hussain, Q.; Lyu, S.H.; Zheng, G.H.; Liu, Y.S. A comparative genomics approach for analysis of complete mitogenomes of five Actinidiaceae plants. Genes 2022, 13, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, A.; Petersen, G.; Seberg, O. Mitochondrial genome evolution in parasitic plants. BMC Evol. Biol. 2019, 19, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, J.; Becklund, L.; Carey, S.; Fabre, P. What is the “modified” CTAB protocol? Characterizing modifications to the CTAB DNA extraction protocol. Appl. Plant Sci. 2023, 11, e11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, M.; Yuan, J.; Lin, Y.; Pevzner, P.A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y.; Wu, R.; Wang, Y. Patterns and influencing factors of synonymous codon usage in porcine circovirus. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2013, 41, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Jiang, S.; Guo, B.; Guo, J.; Cao, L.; Zhang, W. Mitochondrial genomic characteristics and phylogenetic analysis of 21 species of poaceae. Genom. Appl. Biol. 2024, 43, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.Q.; Liao, X.Z.; Zhang, X.N.; Tembrock, L.R.; Broz, A. Genomic architectural variation of plant mitochondria—A review of multichromosomal structuring. J. Syst. Evol. 2022, 60, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, I.; Melonek, J.; Bohne, A.; Nickelsen, J.; Schmitz-Linneweber, C. Plant organellar RNA maturation. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 1727–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Wang, C.; Lin, Y. Sweet potato gene editing and breeding technologies: Research progress and future prospects. Adv. Resour. Res. 2025, 5, 852–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doré, G.; Barloy, D.; Barloy-Hubler, F. De novo hybrid assembly unveils multi-chromosomal mitochondrial genomes in Ludwigia species, highlighting genomic recombination, gene transfer, and RNA editing events. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.; Xing, D.; Su, X.; Guan, C. Comparison and phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial genome among Lycium barbarum and other Solanaceae plants. Genom. Appl. Biol. 2024, 43, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mower, J.P.; Stefanović, S.; Hao, W.; Gummow, J.S.; Jain, K.; Ahmed, D.; Palmer, J.D. Horizontal acquisition of multiple mitochondrial genes from a parasitic plant followed by gene conversion with host mitochondrial genes. BMC Biol. 2010, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, P.J.; Lupski, J.R.; Rosenberg, S.M.; Ira, G. Mechanisms of change in gene copy number. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yuan, J.; Liu, J.; Liang, J.; Chen, J.Q. Codon usage bias and determining forces in green plant mitochondrial genomes. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011, 54, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, X. Codon usage characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the mitochondrial genome in Hemerocallis citrina. BMC Genom. Data 2024, 25, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.Z.; Wei, W.; Qin, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, A.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Guo, F.B. Co-adaption of tRNA gene copy number and amino acid usage influences translation rates in three life domains. DNA Res. 2017, 24, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, M.P.; Acharya, D.; Chakraborty, S.; Ghosh, T.C. The combined influence of codon composition and tRNA copy number regulates translational efficiency by influencing synonymous nucleotide substitution. Gene 2020, 745, 144640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backert, S.; Nielsen, B.L.; Börner, T. The mystery of the rings: Structure and replication of mitochondrial genomes from higher plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1997, 2, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, F.; Carapelli, A.; Frati, F. Repeated regions in mitochondrial genomes: Distribution, origin and evolutionary significance. Mitochondrion 2012, 12, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Mitogenome Size/kb | G + C Content/% | Number of ORF | Number of RNA Editing Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ipomoea aquatica | 296.652 | 44.13 | 315 | 162 |

| Ipomoea quamoclit | 293.939 | 44.25 | 326 | 206 |

| Ipomoea biflora | 278.121 | 44.16 | 324 | 207 |

| Ipomoea batatas | 257.880 | 44.25 | 306 | 215 |

| Ipomoea nil | 265.768 | 44.45 | 324 | 182 |

| Ipomoea trifida | 264.698 | 44.15 | 310 | 223 |

| Ipomoea triloba | 160.302 | 43.89 | 298 | 165 |

| Ipomoea pes-caprae | 106.281 | 44.82 | 305 | 29 |

| Genes | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks |

|---|---|---|---|

| atp1 | 0.9753 | 1.0788 | 0.9041 |

| atp4 | 1.0303 | 0.9026 | 1.1414 |

| atp6 | 0.9664 | 1.1245 | 0.8594 |

| atp8 | 1.0080 | 0.9694 | 1.0398 |

| atp9 | 1.0737 | 0.8116 | 1.3230 |

| ccmB | 0.9737 | 1.0837 | 0.8985 |

| ccmC | 0.9755 | 1.0680 | 0.9134 |

| ccmFc | 1.0048 | 0.9828 | 1.0223 |

| ccmFc1 | 1.0273 | 0.9330 | 1.1011 |

| ccmFc2 | 1.0055 | 0.9794 | 1.0266 |

| ccmFn | 1.0168 | 0.9448 | 1.0762 |

| Cob | 0.9903 | 1.0335 | 0.9582 |

| cox1 | 0.9616 | 1.1156 | 0.8619 |

| cox2 | 0.9602 | 1.1375 | 0.8441 |

| cox3 | 0.9554 | 1.1314 | 0.8444 |

| matR | 0.9843 | 1.0488 | 0.9385 |

| mttB | 1.0448 | 0.8694 | 1.2018 |

| nad1 | 1.0068 | 0.9804 | 1.0268 |

| nad2 | 1.0092 | 0.9721 | 1.0381 |

| nad3 | 0.9160 | 1.2834 | 0.7135 |

| nad4 | 0.9887 | 1.0401 | 0.9506 |

| nad4l | 0.9580 | 1.1435 | 0.8378 |

| nad5 | 0.9880 | 1.0427 | 0.9475 |

| nad6 | 1.0672 | 0.8007 | 1.3329 |

| nad7 | 0.9340 | 1.2797 | 0.7299 |

| nad9 | 0.9757 | 1.0966 | 0.8897 |

| rpl5 | 1.0187 | 0.9421 | 1.0813 |

| rpl10 | 1.0335 | 0.8875 | 1.1644 |

| rpl16 | 0.9217 | 1.2830 | 0.7184 |

| rps1 | 0.9813 | 1.0552 | 0.9301 |

| rps3 | 0.9973 | 1.0096 | 0.9878 |

| rps4 | 1.00136 | 0.9948 | 1.0066 |

| rps7 | 0.9592 | 1.1453 | 0.8374 |

| rps10 | 0.9677 | 1.1224 | 0.8622 |

| rps12 | 0.9916 | 1.0328 | 0.9601 |

| rps13 | 0.9969 | 1.0147 | 0.9825 |

| rps14 | 1.0288 | 0.8943 | 1.1504 |

| rps19 | 0.9449 | 1.2618 | 0.7489 |

| sdh4 | 1.0179 | 0.9451 | 1.0770 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, M.; Zhang, C.; Hou, W.; Li, Y. Comprehensive Analysis of Mitochondrial Genomic Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Plant Genus Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) Species. Biology 2025, 14, 1696. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121696

Xiao M, Zhang C, Hou W, Li Y. Comprehensive Analysis of Mitochondrial Genomic Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Plant Genus Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) Species. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1696. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121696

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Mengya, Cheng Zhang, Wenbang Hou, and Youjun Li. 2025. "Comprehensive Analysis of Mitochondrial Genomic Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Plant Genus Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) Species" Biology 14, no. 12: 1696. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121696

APA StyleXiao, M., Zhang, C., Hou, W., & Li, Y. (2025). Comprehensive Analysis of Mitochondrial Genomic Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Plant Genus Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) Species. Biology, 14(12), 1696. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121696