Drosophila miR-33-5p Suppresses Cell Growth by Inhibiting ERK Signaling

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Transfection

2.2. Plasmid Construction

2.3. Determination of miRNA and mRNA Levels

2.4. Cell Proliferation and Death

2.5. Gene Ontology (GO) Term Analysis

2.6. Western Blotting

2.7. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

2.8. dsRNA Generation

2.9. Drosophila Melanogaster

2.10. Analysis of Adult Wings

2.11. Immunostaining of Wing Discs

2.12. Analysis of Wing Disc Size

3. Results

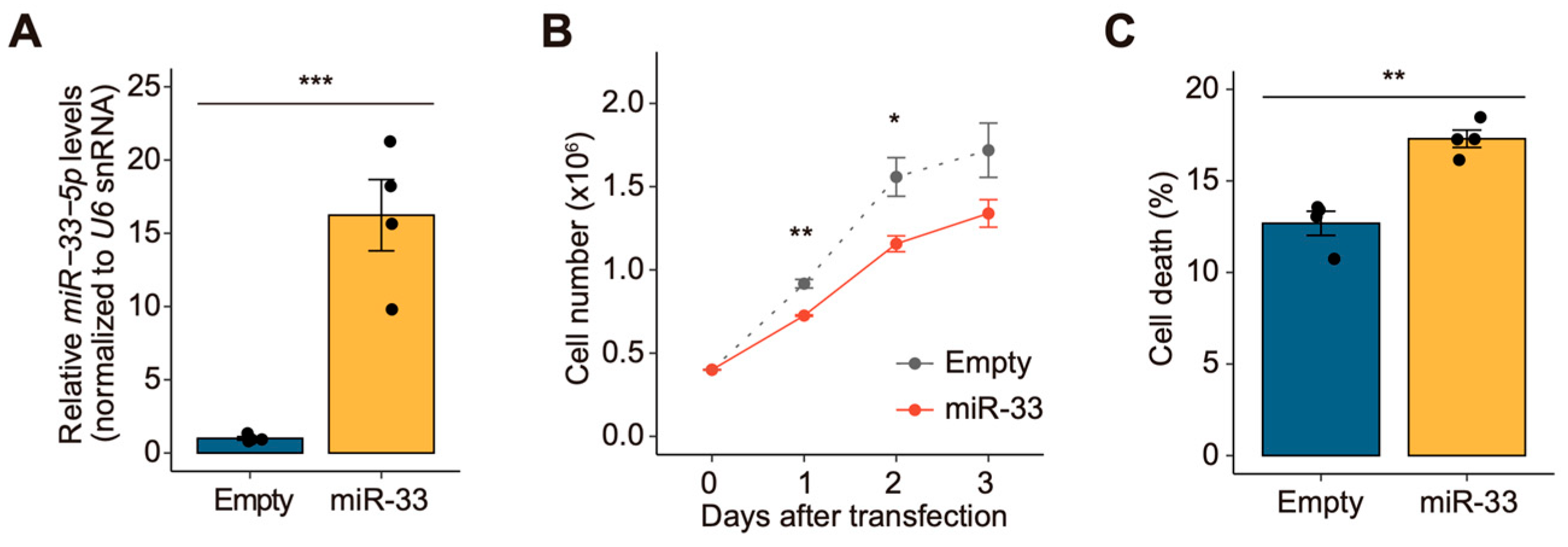

3.1. miR-33 Negatively Regulates Cell Growth in Drosophila S2 Cells

3.2. miR-33-5p Suppresses Ras64B in Drosophila

3.3. Ras64B Is Involved in Cell Proliferation in S2 Cells

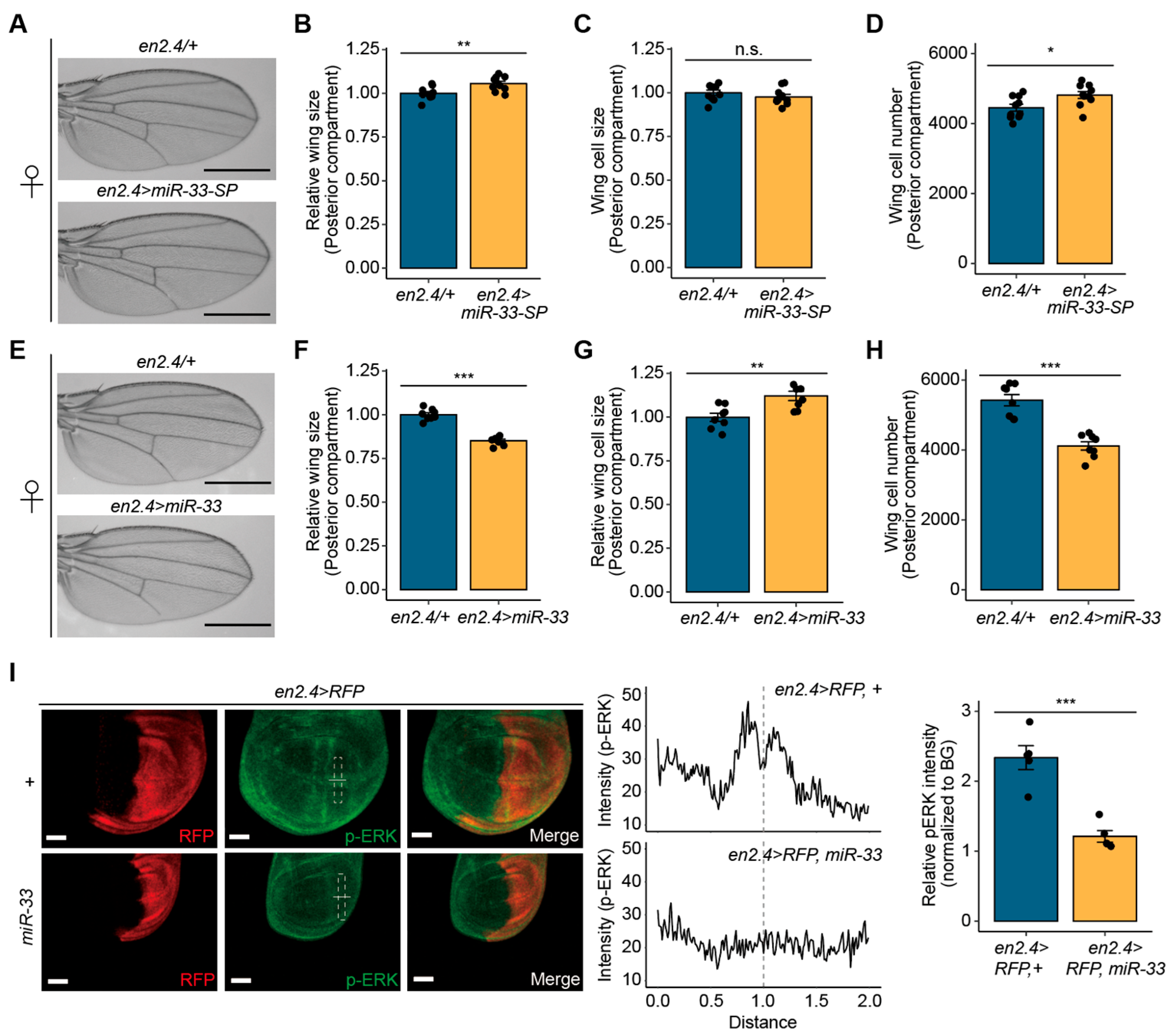

3.4. miR-33 Regulates Drosophila Wing Size

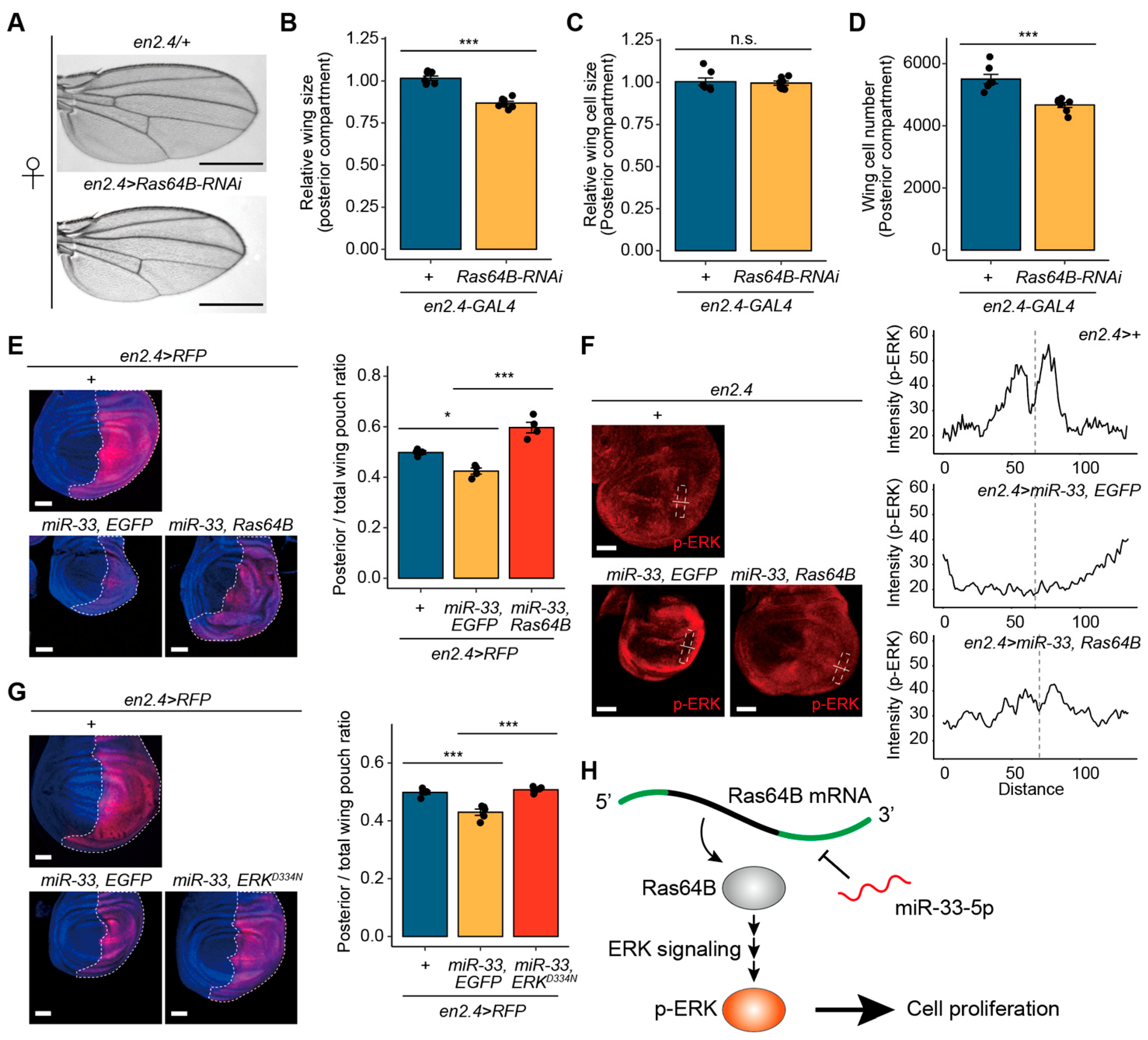

3.5. miR-33-Mediated Wing Growth Defects in Drosophila Are Linked to Ras64B

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neto-Silva, R.M.; Wells, B.S.; Johnston, L.A. Mechanisms of growth and homeostasis in the Drosophila wing. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009, 25, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Lopez, L.A.; Franch-Marro, X.; Vincent, J.P. Wingless promotes proliferative growth in a gradient-independent manner. Sci. Signal 2009, 2, ra60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kango-Singh, M.; Singh, A. Regulation of organ size: Insights from the Drosophila Hippo signaling pathway. Dev. Dyn. 2009, 238, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriskanthadevan-Pirahas, S.; Lee, J.; Grewal, S.S. The EGF/Ras pathway controls growth in Drosophila via ribosomal RNA synthesis. Dev. Biol. 2018, 439, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanshu, D.K.; Nissley, D.V.; McCormick, F. RAS Proteins and Their Regulators in Human Disease. Cell 2017, 170, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voice, J.K.; Klemke, R.L.; Le, A.; Jackson, J.H. Four human ras homologs differ in their abilities to activate Raf-1, induce transformation, and stimulate cell motility. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 17164–17170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.M.; Cox, A.D.; Drivas, G.; Rush, M.G.; D’Eustachio, P.; Der, C.J. Aberrant function of the Ras-related protein TC21/R-Ras2 triggers malignant transformation. Mol. Cell Biol. 1994, 14, 4108–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prober, D.A.; Edgar, B.A. Ras1 promotes cellular growth in the Drosophila wing. Cell 2000, 100, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guichard, A.; Biehs, B.; Sturtevant, M.A.; Wickline, L.; Chacko, J.; Howard, K.; Bier, E. Rhomboid and Star interact synergistically to promote EGFR/MAPK signaling during Drosophila wing vein development. Development 1999, 126, 2663–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prober, D.A.; Edgar, B.A. Interactions between Ras1, dMyc, and dPI3K signaling in the developing Drosophila wing. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 2286–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, A.H.; Perrimon, N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 1993, 118, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebert, L.F.R.; MacRae, I.J. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.; Kim, C.J.; Shin, B.H.; Lim, D.H. The Biological Roles of microRNAs in Drosophila Development. Insects 2024, 15, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths-Jones, S.; Grocock, R.J.; van Dongen, S.; Bateman, A.; Enright, A.J. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D140–D144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, J.; Lim, S.F.; Cohen, S.M. Drosophila miR-14 regulates insulin production and metabolism through its target, sugarbabe. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2748–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, N.; Jang, D.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, J.; Jeon, J.W.; Lim, D.H. Ecdysone-induced microRNA miR-276a-3p controls developmental growth by targeting the insulin-like receptor in Drosophila. Insect Mol. Biol. 2023, 32, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.J.; Jang, D.; Lim, D.H. Drosophila miR-263b-5p controls wing developmental growth by targeting Akt. Anim. Cells Syst. 2025, 29, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, S.; Lee, J.H.; Jin, H.; Nam, J.; Namkoong, B.; Lee, G.; Chung, J.; Kim, V.N. Conserved MicroRNA miR-8/miR-200 and its target USH/FOG2 control growth by regulating PI3K. Cell 2009, 139, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; de Navas, L.F.; Hu, F.; Sun, K.; Mavromatakis, Y.E.; Viets, K.; Zhou, C.; Kavaler, J.; Johnston, R.J.; Tomlinson, A.; et al. The mir-279/996 cluster represses receptor tyrosine kinase signaling to determine cell fates in the Drosophila eye. Development 2018, 145, dev159053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerbaux, L.A.; Schultz, H.; Roman-Holba, S.; Ruan, D.F.; Yu, R.; Lamb, A.M.; Bommer, G.T.; Kennell, J.A. The microRNA miR-33 is a pleiotropic regulator of metabolic and developmental processes in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Dyn. 2021, 250, 1634–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelheit, O.; Hanukoglu, A.; Hanukoglu, I. Simple and efficient site-directed mutagenesis using two single-primer reactions in parallel to generate mutants for protein structure-function studies. BMC Biotechnol. 2009, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ro, S.; Park, C.; Jin, J.; Sanders, K.M.; Yan, W. A PCR-based method for detection and quantification of small RNAs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 351, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ro, S.; Yan, W. Detection and quantitative analysis of small RNAs by PCR. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 629, pp. 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, J.G.; Stark, A.; Johnston, W.K.; Kellis, M.; Bartel, D.P.; Lai, E.C. Evolution, biogenesis, expression, and target predictions of a substantially expanded set of Drosophila microRNAs. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 1850–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessels, H.H.; Lebedeva, S.; Hirsekorn, A.; Wurmus, R.; Akalin, A.; Mukherjee, N.; Ohler, U. Global identification of functional microRNA-mRNA interactions in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Hu, E.; Cai, Y.; Xie, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhan, L.; Tang, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, R.; et al. Using clusterProfiler to characterize multiomics data. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 3292–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, J.; French, V.; Partridge, L. Joint regulation of cell size and cell number in the wing blade of Drosophila melanogaster. Genet. Res. 1997, 69, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesevski, M.; Dworkin, I. Genetic and environmental canalization are not associated among altitudinally varying populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 2020, 74, 1755–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.H.; Choi, M.S.; Jeon, J.W.; Lee, Y.S. MicroRNA miR-252-5p regulates the Notch signaling pathway by targeting Rab6 in Drosophila wing development. Insect Sci. 2023, 30, 1431–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Cuesta, P.; Ruiz-Gomez, A.; Molnar, C.; Organista, M.F.; Resnik-Docampo, M.; Falo-Sanjuan, J.; Lopez-Varea, A.; de Celis, J.F. Ras2, the TC21/R-Ras2 Drosophila homologue, contributes to insulin signalling but is not required for organism viability. Dev. Biol. 2020, 461, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, J.H.; Koh, H.; Lee, S.Y.; Jang, C.; Chung, C.J.; Sung, J.H.; Blenis, J.; Chung, J. Inhibition of ERK-MAP kinase signaling by RSK during Drosophila development. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 3056–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biteau, B.; Jasper, H. EGF signaling regulates the proliferation of intestinal stem cells in Drosophila. Development 2011, 138, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Ha, N.; Fores, M.; Xiang, J.; Glasser, C.; Maldera, J.; Jimenez, G.; Edgar, B.A. EGFR/Ras Signaling Controls Drosophila Intestinal Stem Cell Proliferation via Capicua-Regulated Genes. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafuik, C.; Steller, H. A gain-of-function germline mutation in Drosophila ras1 affects apoptosis and cell fate during development. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurada, P.; White, K. Ras promotes cell survival in Drosophila by downregulating hid expression. Cell 1998, 95, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, T.; Riesgo-Escovar, J.; Liu, X.; Bausenwein, B.S.; Deak, P.; Maroy, P.; Hafen, E. DOS, a novel pleckstrin homology domain-containing protein required for signal transduction between sevenless and Ras1 in Drosophila. Cell 1996, 85, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Reich, A.; Sapir, A.; Shilo, B. Sprouty is a general inhibitor of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Development 1999, 126, 4139–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilmos, P.; Sousa-Neves, R.; Lukacsovich, T.; Marsh, J.L. Crossveinless defines a new family of Twisted-gastrulation-like modulators of bone morphogenetic protein signalling. EMBO Rep. 2005, 6, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davalos, A.; Goedeke, L.; Smibert, P.; Ramirez, C.M.; Warrier, N.P.; Andreo, U.; Cirera-Salinas, D.; Rayner, K.; Suresh, U.; Pastor-Pareja, J.C.; et al. miR-33a/b contribute to the regulation of fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9232–9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, T.; Kim, N.; Park, Y.J.; Cha, S.; Lee, Y.S.; Lim, D.-H. Drosophila miR-33-5p Suppresses Cell Growth by Inhibiting ERK Signaling. Biology 2025, 14, 1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121693

Lee T, Kim N, Park YJ, Cha S, Lee YS, Lim D-H. Drosophila miR-33-5p Suppresses Cell Growth by Inhibiting ERK Signaling. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121693

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Taeheon, Nayeon Kim, Ye Jin Park, Seungeun Cha, Young Sik Lee, and Do-Hwan Lim. 2025. "Drosophila miR-33-5p Suppresses Cell Growth by Inhibiting ERK Signaling" Biology 14, no. 12: 1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121693

APA StyleLee, T., Kim, N., Park, Y. J., Cha, S., Lee, Y. S., & Lim, D.-H. (2025). Drosophila miR-33-5p Suppresses Cell Growth by Inhibiting ERK Signaling. Biology, 14(12), 1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121693