Modeling Glioblastoma for Translation: Strengths and Pitfalls of Preclinical Studies

Simple Summary

Abstract

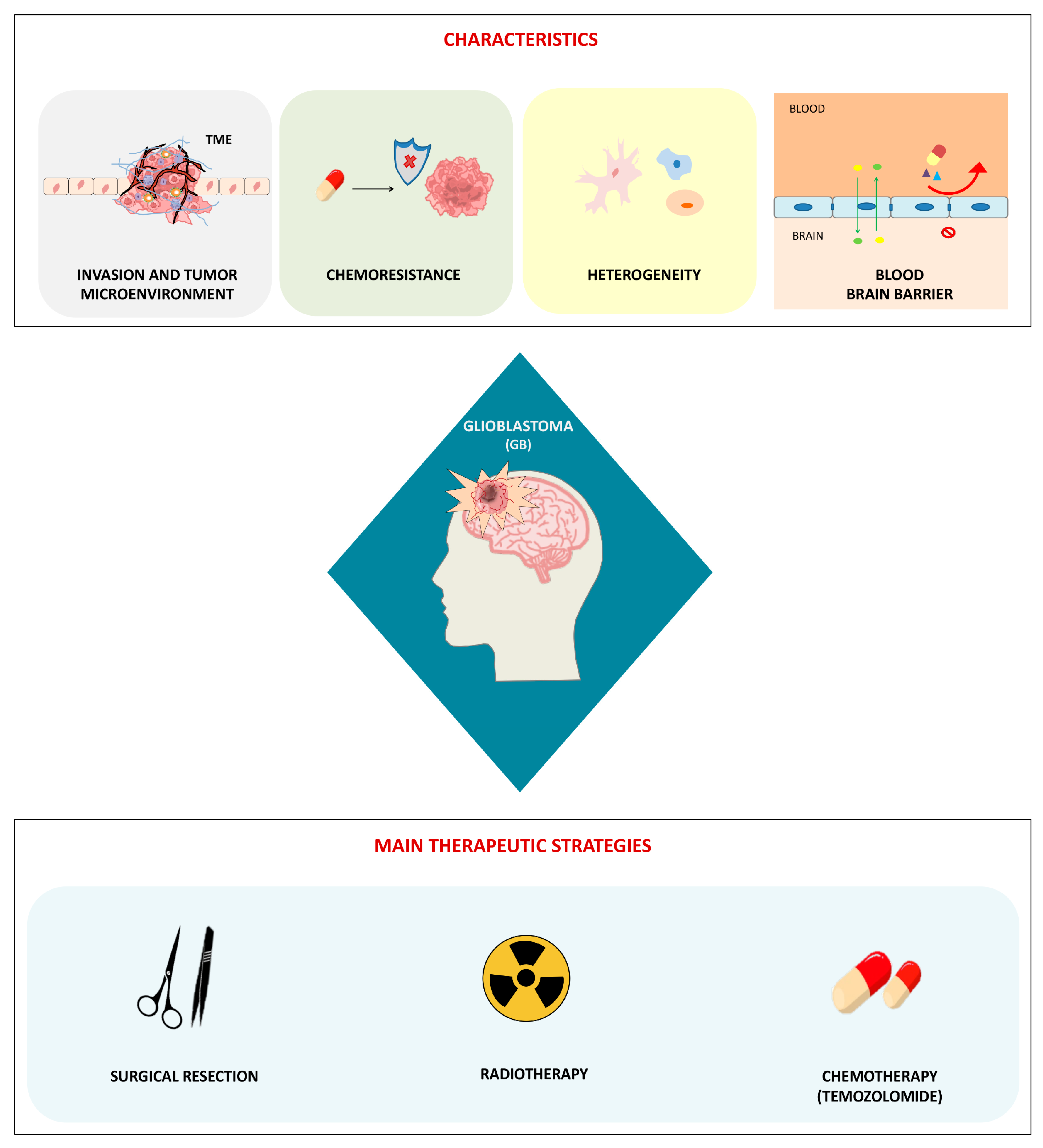

1. Introduction

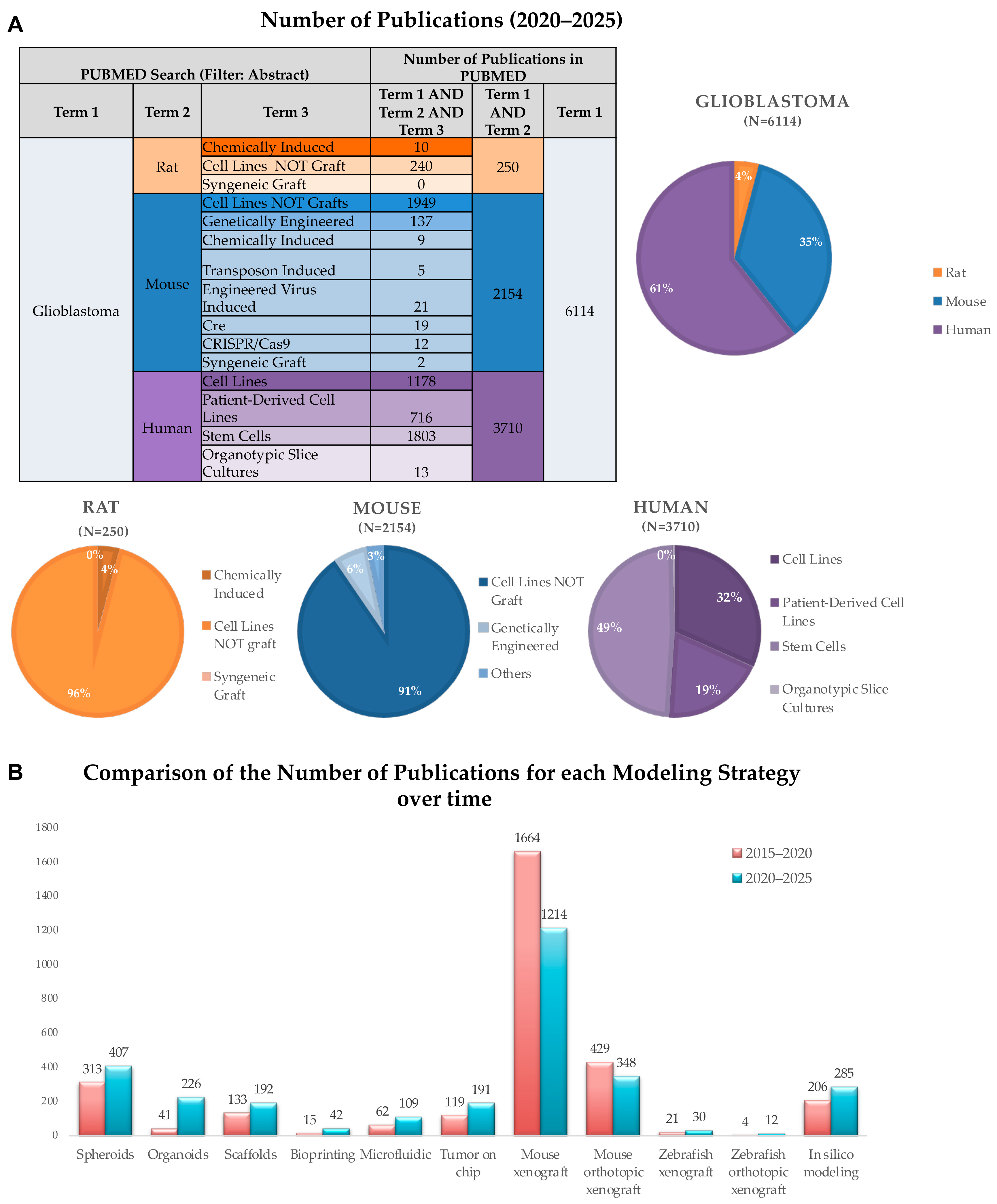

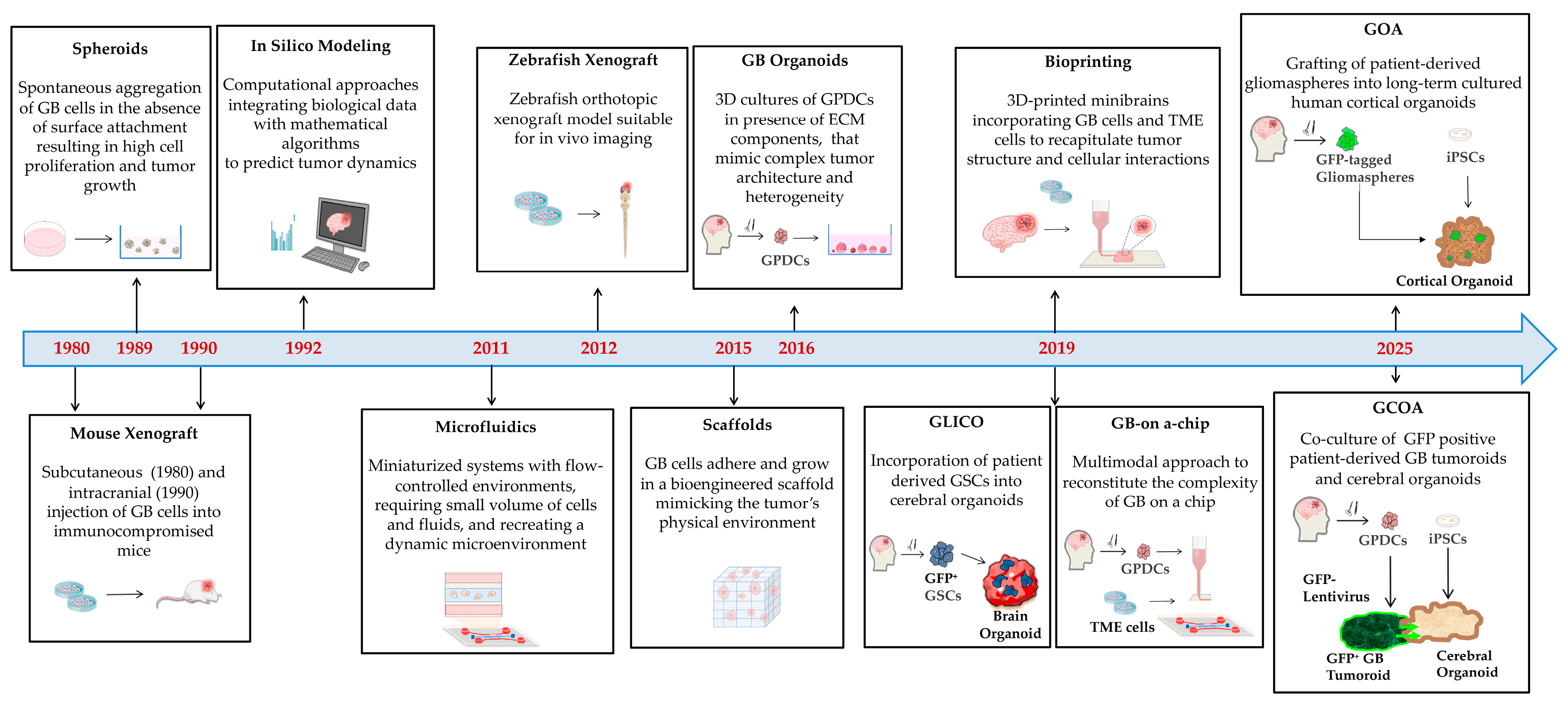

2. Glioblastoma Preclinical Models: An Overview

3. Glioblastoma Origin

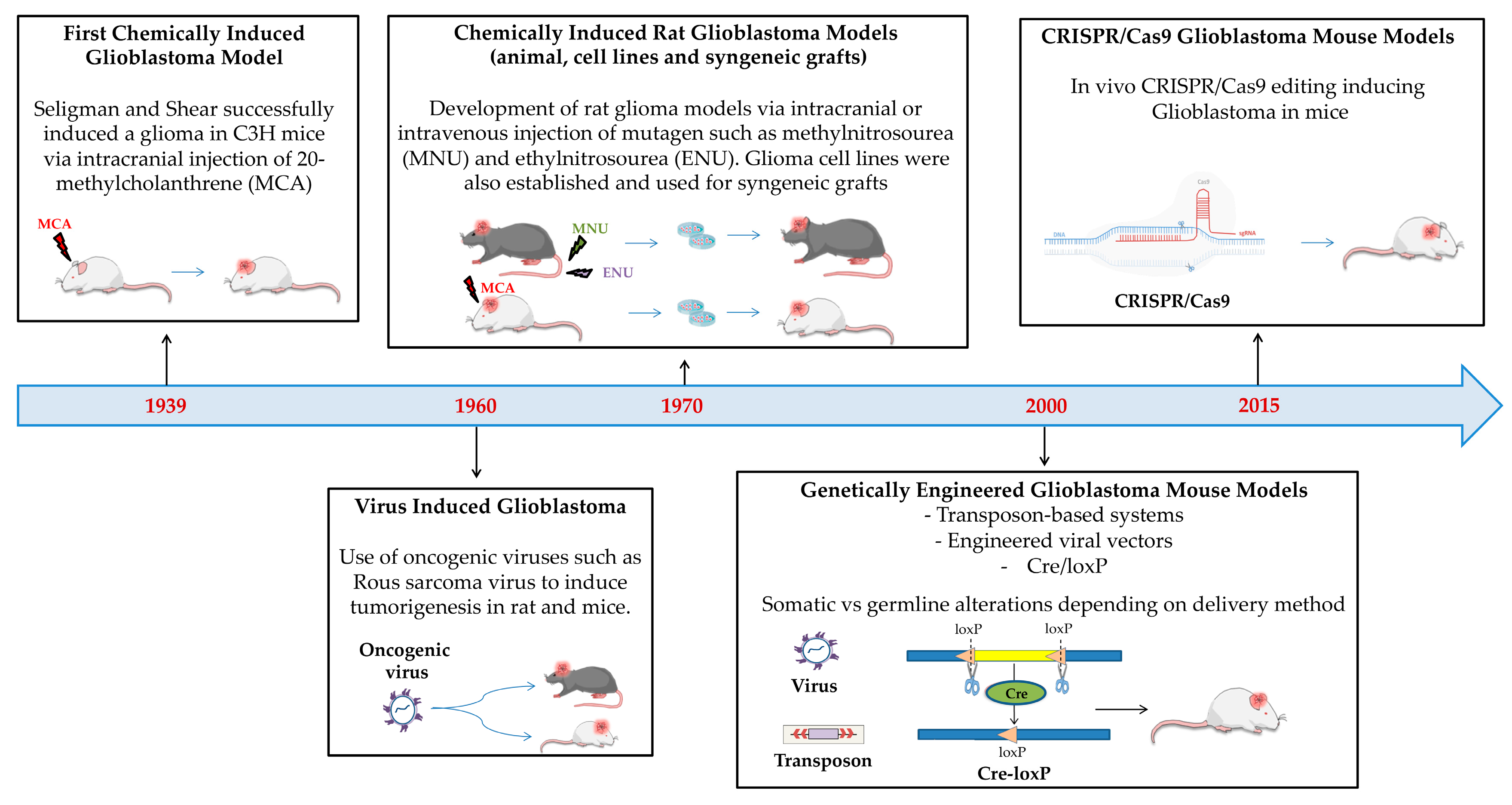

3.1. Animal

3.1.1. Origin and Characteristics

Chemically and Genetically Induced In Vivo Models

Cell Lines

Syngeneic Grafting Models

3.1.2. Purposes, Strengths and Weaknesses

3.2. Human

| Origin | Model Type | Generation | Effort | Representativity Respect to Patient GB | Complexity | Purpose | Throughput | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | Time | ECM | TME | BBB | Applications | |||||

| Human | Conventional cell lines | Isolation and immortalization | L | L/M | L Differ from patient GB both genetically and phenotypically; Can accumulate genetic mutations in culture | - | - | - | Cell proliferation, metabolism, viability, and migration; Drug assays; Resistance to therapy | H |

| Patient derived cell lines | Isolation from fresh biopsies and limited passage in culture | M | L/M | H Maintain the genotypic and phenotypic features of the tumor of origin; Reflect GB patient variability | - | - | - | Cell proliferation, viability, and migration; Response to therapy; Personalized medicine | M | |

| Glioblastoma stem cells | Isolation from fresh GB biopsies or iPSC reprogramming or conventional cell lines derivation; culturing in absence of serum and presence of specific factors (EGF, bFGF) | M | L/M | H if derived by GB patients; Can differentiate also in TME cells | - | -/+ | - | Cell proliferation and invasion; Resistance to therapy; In vivo tumor formation; Personalized medicine (if derived by GB patients) | M | |

| Patient derived organotypic slice culture | Removal of GB tissues, cutting in sections and culturing for limited time | M/H | M/H | H Maintain the genotypic and phenotypic features of the tumor of origin; Reflect GB patient variability | + | + | + | Cell proliferation, death, and invasion; immune response; drug assays; resistance to therapy; personalized medicine | L | |

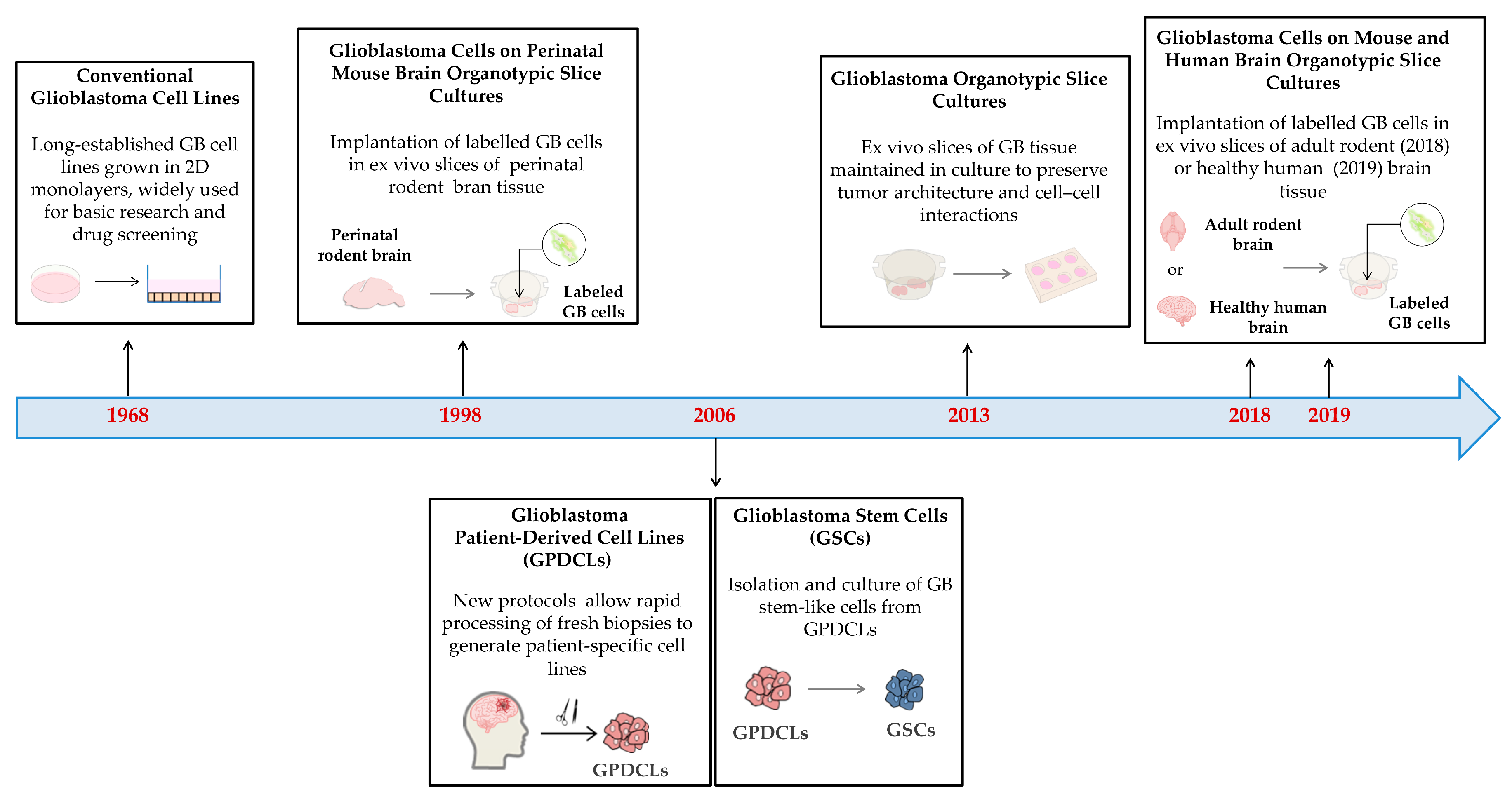

3.2.1. Origin and Characteristics

Conventional Cell Lines

Patient-Derived Cell Lines

Glioblastoma Stem Cells

Patient-Derived Organotypic Slice Cultures

3.2.2. Purpose, Strengths and Weaknesses

4. Cell Culture Modeling Strategies

4.1. 2D Models

4.1.1. Origin and Characteristics

4.1.2. Purpose, Strengths and Limitations

4.2. 3D Models

4.2.1. Origin and Characteristics

Spheroids

Tumor-like Organoids or Tumoroids

Cerebral Organoid Glioma (GLICO) and Other Co-Culture Systems

Scaffold-Based Models

4.2.2. Purpose, Strengths and Limitations

5. Modeling of the Interactions with Glioblastoma Microenvironment and Blood–Brain Barrier

5.1. In Vitro or Ex Vivo

5.1.1. Origin and Characteristics

Bioprinting

Microfluidic

GB-on-a-chip

5.1.2. Purpose, Strengths and Limitations

5.2. In Vivo Graft Models

5.2.1. Origin and Characteristics

Mouse Xenografts

Zebrafish Xenografts

5.2.2. Purpose, Strengths and Limitations

5.3. In Silico Modeling

5.3.1. Origin and Characteristics

5.3.2. Purpose, Strengths and Limitations

6. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

- Choice of the most suitable GB model(s)

- 2.

- Identification of guidelines and standardization of procedures for model usage

- 3.

- Open platforms and integrations of the different models.

- 4.

- Development of novel multimodal integrated approach

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-Dimensional |

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| BBB | Blood–Brain Barrier |

| bFGF | basic Fibroblast Growth actor |

| BRCA1 | BReast CAncer gene 1 |

| BTB | Blood-Tumor Barrier |

| CAR-T | Chimeric Antigen Receptor T |

| ECM | ExtraCellular Matrix |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| EGFP | Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein |

| EMT | Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition |

| ENU | Ethylnitrosourea |

| GAMs | Glioblastoma-associated macrophages |

| GB | Glioblastoma |

| GBO | Glioblastoma Organoid |

| GTN | Glioblastoma Therapeutics Network |

| GCO | Glioblastoma Cortical Organoid |

| GCOA | Glioblastoma-Cerebral Organoid Assembloid |

| GEMMs | Genetically Engineered Mouse Models |

| GLICO | Cerebral Organoid Glioma |

| GPDCs | Glioblastoma Patient-Derived Cells |

| GPDCL | Glioblastoma Patient-Derived Cells lines |

| GSCs | Glioblastoma Stem Cells |

| H | High |

| hiPSCs | human-induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| JAK/STAT | Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| L | Low |

| M | Medium |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision-Making |

| MCTS | Multicellular Tumor Spheroids |

| MGMT | O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase |

| MNU | Methylnitrosourea |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| NCI | National Cancer Institute |

| NOD | Non-Obese Diabetic |

| OMS | Organotypic Multicellular Spheroids |

| PDCLs | Patient-Derived Cells lines |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| PDGFR | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor |

| PDMS | PolyDiMethylSiloxane |

| PDOX | Patient-Derived Orthotopic Xenograft |

| PDX | Patient-Derived Xenograft |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase |

| SCID | Severe Combined ImmunoDeficient |

| SOPs | Standard Operating Procedures |

| TME | Tumor MicroEnvironment |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

References

- Furnari, F.B.; Fenton, T.; Bachoo, R.M.; Mukasa, A.; Stommel, J.M.; Stegh, A.; Hahn, W.C.; Ligon, K.L.; Louis, D.N.; Brennan, C.; et al. Malignant Astrocytic Glioma: Genetics, Biology, and Paths to Treatment. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 2683–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Dey, D.; Barik, D.; Mohapatra, I.; Kim, S.; Sharma, M.; Prasad, S.; Wang, P.; Singh, A.; Singh, G. Glioblastoma at the crossroads: Current understanding and future therapeutic horizons. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G.L. Challenges and Promise for Glioblastoma Treatment through Extracellular Vesicle Inquiry. Cells 2024, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, L.C.; Veeravagu, A.; Hsu, A.R.; Tse, V.C.K. Recurrent Glioblastoma Multiforme: A Review of Natural History and Management Options. Neurosurg. Focus 2006, 20, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherriff, J.; Tamangani, J.; Senthil, L.; Cruickshank, G.; Spooner, D.; Jones, B.; Brookes, C.; Sanghera, P. Patterns of Relapse in Glioblastoma Multiforme Following Concomitant Chemoradiotherapy with Temozolomide. Br. J. Radiol. 2013, 86, 20120414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G.L.; Kralj-Iglič, V. Pathological and Therapeutic Significance of Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer Cell Migration and Metastasis. Cancers 2023, 15, 4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, M.A.; Huang, R.Y.Y.J.; Jackson, R.A.A.; Thiery, J.P.P. Emt: 2016. Cell 2016, 166, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegi, M.E.; Diserens, A.-C.; Gorlia, T.; Hamou, M.-F.; de Tribolet, N.; Weller, M.; Kros, J.M.; Hainfellner, J.A.; Mason, W.; Mariani, L.; et al. MGMT Gene Silencing and Benefit from Temozolomide in Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlashi, E.; Lagadec, C.; Vergnes, L.; Matsutani, T.; Masui, K.; Poulou, M.; Popescu, R.; Della Donna, L.; Evers, P.; Dekmezian, C.; et al. Metabolic State of Glioma Stem Cells and Nontumorigenic Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16062–16067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathia, J.D.; Mack, S.C.; Mulkearns-Hubert, E.E.; Valentim, C.L.L.; Rich, J.N. Cancer Stem Cells in Glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.P.; Tirosh, I.; Trombetta, J.J.; Shalek, A.K.; Gillespie, S.M.; Wakimoto, H.; Cahill, D.P.; Nahed, B.V.; Curry, W.T.; Martuza, R.L.; et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Highlights Intratumoral Heterogeneity in Primary Glioblastoma. Science 2014, 344, 1396–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaak, R.G.W.; Hoadley, K.A.; Purdom, E.; Wang, V.; Qi, Y.; Wilkerson, M.D.; Miller, C.R.; Ding, L.; Golub, T.; Mesirov, J.P.; et al. Integrated Genomic Analysis Identifies Clinically Relevant Subtypes of Glioblastoma Characterized by Abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, D.A.; Wen, P.Y. Glioma in 2014: Unravelling Tumour Heterogeneity-Implications for Therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 12, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneman, R.; Prat, A. The Blood–Brain Barrier. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a020412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Shusta, E.V. Blood–Brain Barrier Modulation to Improve Glioma Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Zaldívar, H.M.; Polakovicova, I.; Salas-Huenuleo, E.; Corvalán, A.H.; Kogan, M.J.; Yefi, C.P.; Andia, M.E. Extracellular Vesicles through the Blood–Brain Barrier: A Review. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Gan, S.; Roy, S.; Hasan, I.; Zhang, B.; Guo, B. Emerging Extracellular Vesicle-Based Carriers for Glioblastoma Diagnosis and Therapy. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 10904–10938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Sane, R.; Oberoi, R.; Ohlfest, J.R.; Elmquist, W.F. Delivery of Molecularly Targeted Therapy to Malignant Glioma, a Disease of the Whole Brain. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2011, 13, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalamarty, S.S.K.; Filipczak, N.; Li, X.; Subhan, M.A.; Parveen, F.; Ataide, J.A.; Rajmalani, B.A.; Torchilin, V.P. Mechanisms of Resistance and Current Treatment Options for Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM). Cancers 2023, 15, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.W.; Quail, D.F. Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma: Current Progress and Challenge. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 676301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew-Schmitt, S.; Peindl, M.; Neundorf, P.; Dandekar, G.; Metzger, M.; Nickl, V.; Appelt-Menzel, A. Blood-Tumor Barrier in Focus—Investigation of Glioblastoma-Induced Effects on the Blood-Brain Barrier. J. Neurooncol. 2024, 170, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angom, R.S.; Nakka, N.M.R.; Bhattacharya, S. Advances in Glioblastoma Therapy: An Update on Current Approaches. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medikonda, R.; Dunn, G.; Rahman, M.; Fecci, P.; Lim, M. A Review of Glioblastoma Immunotherapy. J. Neurooncol. 2021, 151, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sferruzza, G.; Consoli, S.; Dono, F.; Evangelista, G.; Giugno, A.; Pronello, E.; Rollo, E.; Romozzi, M.; Rossi, L.; Pensato, U. A Systematic Review of Immunotherapy in High-Grade Glioma: Learning from the Past to Shape Future Perspectives. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 2561–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantile, F.; Franco, P.; Stoppelli, M.P.; Liguori, G.L. Biological Role and Clinical Relevance of Extracellular Vesicles as Key Mediators of Cell Communication in Cancer. In Biological Membrane Vesicles: Scientific, Biotechnological and Clinical Considerations. Advances in Biomembranes and Lipid Self-Assembly; Elsiever: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.Y.; Li, Y.J.; Hu, X.B.; Huang, S.; Luo, S.; Tang, T.; Xiang, D.X. Exosomes and Biomimetic Nanovesicles-Mediated Anti-Glioblastoma Therapy: A Head-to-Head Comparison. J. Control. Release 2021, 336, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.K. A Critical Overview of Targeted Therapies for Glioblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusak, A.; Wiatrak, B.; Krawczyńska, K.; Górnicki, T.; Zagórski, K.; Zadka, Ł.; Fortuna, W. Starting Points for the Development of New Targeted Therapies for Glioblastoma Multiforme. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 51, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldape, K.; Brindle, K.M.; Chesler, L.; Chopra, R.; Gajjar, A.; Gilbert, M.R.; Gottardo, N.; Gutmann, D.H.; Hargrave, D.; Holland, E.C.; et al. Challenges to Curing Primary Brain Tumours. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Rahman, R. Evolution of Preclinical Models for Glioblastoma Modelling and Drug Screening. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 27, 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.F.; Kaur, B. Rat Brain Tumor Models in Experimental Neuro-Oncology: The C6, 9L, T9, RG2, F98, BT4C, RT-2 and CNS-1 Gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 2009, 94, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, A.M.; Shear, M.J.; Alexander, L. Studies in Carcinogenesis: VIII. Experimental Production of Brain Tumors in Mice with Methylcholanthrene. Am. J. Cancer 1939, 37, 364–395. [Google Scholar]

- Wilfong, R.F.; Bigner, D.D.; Self, D.J.; Wechsler, W. Brain Tumor Types Induced by the Schmidt-Ruppin Strain of Rous Sarcoma Virus in Inbred Fischer Rats. Acta Neuropathol. 1973, 25, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, K.; Hoshino, H.; Kiuchi, Y.; Nakano, G.; Nagamachi, Y. Potential Usefulness of a Cultured Glioma Cell Line Induced by Rous Sarcoma Virus in B10.A Mouse as an Immunotherapy Model. Jpn. J. Exp. Med. 1989, 59, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, F.; Jin-Lee, H.J.; Johnson, A.J. Mouse Models of Experimental Glioblastoma; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2021; ISBN 9780645001747. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, U.; Barth, R.F.; Otani, Y.; McCormack, R.; Kaur, B. Rat and Mouse Brain Tumor Models for Experimental Neuro-Oncology Research. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 81, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidek, H.H.; Nielsen, S.L.; Schiller, A.L.; Messer, J. Morphological Studies of Rat Brain Tumors Induced by N-Nitrosomethylurea. J. Neurosurg. 1971, 34, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benda, P.; Lightbody, J.; Sato, G.; Levine, L.; Sweet, W. Differentiated Rat Glial Cell Strain in Tissue Culture. Science 1968, 161, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, L.; Koestner, A.; Wechsler, W. Morphological Characterization of Nitrosourea-Induced Glioma Cell Lines and Clones. Acta Neuropathol. 1980, 51, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausman, J.I.; Shapiro, W.R.; Rall, D.P. Studies on the Chemotherapy of Experimental Brain Tumors: Development of an Experimental Model. Cancer Res. 1970, 30, 2394–2400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fomchenko, E.I.; Holland, E.C. Mouse Models of Brain Tumors and Their Applications in Preclinical Trials. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 5288–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupuleti, V.; Vora, L.; Prasad, R.; Nandakumar, D.N.; Khatri, D.K. Glioblastoma Preclinical Models: Strengths and Weaknesses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, J.; Piontek, G.; Kersting, M.; Schuermann, M.; Kappler, R.; Scherthan, H.; Weghorst, C.; Buzard, G.; Mennel, H. The P16/Cdkn2a/Ink4a Gene Is Frequently Deleted in Nitrosourea-Induced Rat Glial Tumors. Pathobiology 1999, 67, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asai, A.; Miyagi, Y.; Sugiyama, A.; Gamanuma, M.; Hong, S.H.; Takamoto, S.; Nomura, K.; Matsutani, M.; Takakura, K.; Kuchino, Y. Negative Effects of Wild-Type P53 and s-Myc on Cellular Growth and Tumorigenicity of Glioma Cells. Implication of the Tumor Suppressor Genes for Gene Therapy. J. Neurooncol. 1994, 19, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibenaller, Z.A.; Etame, A.B.; Ali, M.M.; Barua, M.; Braun, T.A.; Casavant, T.L.; Ryken, T.C. Genetic Characterization of Commonly Used Glioma Cell Lines in the Rat Animal Model System. Neurosurg. Focus 2005, 19, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, S.; Molinari, A.; Sabatino, G.; Ciafrè, S.A.; Colone, M.; Maira, G.; Anile, C.; Arancia, G.; Mangiola, A. Intratumoral vs Systemic Administration of Meta-Tetrahydroxyphenylchlorin for Photodynamic Therapy of Malignant Gliomas: Assessment of Uptake and Spatial Distribution in C6 Rat Glioma Model. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2008, 21, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szatmári, T.; Lumniczky, K.; Désaknai, S.; Trajcevski, S.; Hídvégi, E.J.; Hamada, H.; Sáfrány, G. Detailed Characterization of the Mouse Glioma 261 Tumor Model for Experimental Glioblastoma Therapy. Cancer Sci. 2006, 97, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraiopoulou, M.E.; Tzamali, E.; Papamatheakis, J.; Sakkalis, V. Phenocopying Glioblastoma: A Review. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 16, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumettis, D.; Kritis, A.; Foroglou, N. C6 Cell Line: The Gold Standard in Glioma Research. Hippokratia 2018, 22, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Doblas, S.; Saunders, D.; Kshirsagar, P.; Pye, Q.; Oblander, J.; Gordon, B.; Kosanke, S.; Floyd, R.A.; Towner, R.A. Phenyl-Tert-Butylnitrone Induces Tumor Regression and Decreases Angiogenesis in a C6 Rat Glioma Model. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solly, F.; Fish, R.; Simard, B.; Bolle, N.; Kruithof, E.; Polack, B.; Pernod, G. Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator Has Antiangiogenic Properties without Effect on Tumor Growth in a Rat C6 Glioma Model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.E.; Jacob, S.; Nagy, A.A.; Abdel-Naim, A.B. Dibromoacetonitrile-Induced Protein Oxidation and Inhibition of Proteasomal Activity in Rat Glioma Cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2008, 179, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zou, H.; Liu, Y.; Dong, X.; Sun, X. Intravenous Administration of Arsenic Trioxide Encapsulated in Liposomes Inhibits the Growth of C6 Gliomas in Rat Brains. J. Chemother. 2008, 20, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, J.; Ionescu, A.; Pouratian, N.; Hamilton, D.K.; Schlesinger, D.; Oskouian, R.J.J.; Sansur, C. Use of Trans Sodium Crocetinate for Sensitizing Glioblastoma Multiforme to Radiation: Laboratory Investigation. J. Neurosurg. 2008, 108, 972–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, R.A.; Gillespie, D.L.; Schwager, A.; Saunders, D.G.; Smith, N.; Njoku, C.E.; Krysiak, R.S., 3rd; Larabee, C.; Iqbal, H.; Floyd, R.A.; et al. Regression of Glioma Tumor Growth in F98 and U87 Rat Glioma Models by the Nitrone OKN-007. Neuro Oncol. 2013, 15, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Barth, R.F.; Wu, G.; Ciesielski, M.J.; Fenstermaker, R.A.; Moffat, B.A.; Ross, B.D.; Wikstrand, C.J. Development of a Syngeneic Rat Brain Tumor Model Expressing EGFRvIII and Its Use for Molecular Targeting Studies with Monoclonal Antibody L8A4. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, A. Genes and Pathways Driving Glioblastomas in Humans and Murine Disease Models. Neurosurg. Rev. 2003, 26, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, T. Comparison Between Human and Rodent Neurons for Persistent Activity Performance: A Biologically Plausible Computational Investigation. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattorelli, N.; Martinez-Muriana, A.; Wolfs, L.; Geric, I.; De Strooper, B.; Mancuso, R. Stem-Cell-Derived Human Microglia Transplanted into Mouse Brain to Study Human Disease. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 1013–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geribaldi-Doldán, N.; Fernández-Ponce, C.; Quiroz, R.N.; Sánchez-Gomar, I.; Escorcia, L.G.; Velásquez, E.P.; Quiroz, E.N. The Role of Microglia in Glioblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10, 603495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontén, J.A.N.; Macintyre, E.H. Long Term Culture of Normal and Neoplastic Human Glia. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1968, 74, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigner, D.D.; Bigner, S.H.; Pontén, J.; Westermark, B.; Mahaley, M.S.; Ruoslahti, E.; Herschman, H.; Eng, L.F.; Wikstrand, C.J. Heterogeneity of Genotypic and Phenotypic Characteristics of Fifteen Permanent Cell Lines Derived from Human Gliomas. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1981, 40, 201–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLendon, R.; Friedman, A.; Bigner, D.; Van Meir, E.G.; Brat, D.J.; Mastrogianakis, G.M.; Olson, J.J.; Mikkelsen, T.; Lehman, N.; Aldape, K.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Characterization Defines Human Glioblastoma Genes and Core Pathways. Nature 2008, 455, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantile, F.; Kisovec, M.; Adamo, G.; Romancino, D.P.; Hočevar, M.; Božič, D.; Bedina Zavec, A.; Podobnik, M.; Stoppelli, M.P.; Kisslinger, A.; et al. A Novel Localization in Human Large Extracellular Vesicles for the EGF-CFC Founder Member CRIPTO and Its Biological and Therapeutic Implications. Cancers 2022, 14, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camerino, I.; Franco, P.; Bajetto, A.; Thellung, S.; Florio, T.; Stoppelli, M.P.; Colucci-D’Amato, L. Ruta Graveolens, but Not Rutin, Inhibits Survival, Migration, Invasion, and Vasculogenic Mimicry of Glioblastoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casciati, A.; Tanori, M.; Gianlorenzi, I.; Rampazzo, E.; Persano, L.; Viola, G.; Cani, A.; Bresolin, S.; Marino, C.; Mancuso, M.; et al. Effects of Ultra-Short Pulsed Electric Field Exposure on Glioblastoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabelli, P.; Coppola, L.; Salvatore, M. Cancer Cell Lines Are Useful Model Systems for Medical Research. Cancers 2019, 11, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Griffiths, S.; Veljanoski, D.; Vaughn-Beaucaire, P.; Speirs, V.; Brüning-Richardson, A. Preclinical Models of Glioblastoma: Limitations of Current Models and the Promise of New Developments. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2021, 23, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircan, T.; Yavuz, M.; Kaya, E.; Akgül, S.; Altuntaş, E. Cellular and Molecular Comparison of Glioblastoma Multiform Cell Lines. Cureus 2021, 13, e16043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kotliarova, S.; Kotliarov, Y.; Li, A.; Su, Q.; Donin, N.M.; Pastorino, S.; Purow, B.W.; Christopher, N.; Zhang, W.; et al. Tumor Stem Cells Derived from Glioblastomas Cultured in BFGF and EGF More Closely Mirror the Phenotype and Genotype of Primary Tumors than Do Serum-Cultured Cell Lines. Cancer Cell 2006, 9, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Hora, C.C.; Schweiger, M.W.; Wurdinger, T.; Tannous, B.A. Patient-Derived Glioma Models: From Patients to Dish to Animals. Cells 2019, 8, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, S.; Garvalov, B.K.; Acker, T. Isolation and Culture of Primary Glioblastoma Cells from Human Tumor Specimens. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1235, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenster, J.D.; Placantonakis, D.G. Establishing Primary Human Glioblastoma Tumorsphere Cultures from Operative Specimens. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1741, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Bergström, T.; Jiang, Y.; Johansson, P.; Marinescu, V.D.; Lindberg, N.; Segerman, A.; Wicher, G.; Niklasson, M.; Baskaran, S.; et al. The Human Glioblastoma Cell Culture Resource: Validated Cell Models Representing All Molecular Subtypes. EBioMedicine 2015, 2, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringer, B.W.; Day, B.W.; D’Souza, R.C.J.; Jamieson, P.R.; Ensbey, K.S.; Bruce, Z.C.; Lim, Y.C.; Goasdoué, K.; Offenhäuser, C.; Akgül, S.; et al. A Reference Collection of Patient-Derived Cell Line and Xenograft Models of Proneural, Classical and Mesenchymal Glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolillo, M.; Comincini, S.; Schinelli, S. In Vitro Glioblastoma Models: A Journey into the Third Dimension. Cancers 2021, 13, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, X.; Chedid, K.; Kalkanis, S.N. Glioblastoma Cell Line-Derived Spheres in Serum-Containing Medium versus Serum-Free Medium: A Comparison of Cancer Stem Cell Properties. Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 41, 1693–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiguro, T.; Ohata, H.; Sato, A.; Yamawaki, K.; Enomoto, T.; Okamoto, K. Tumor-Derived Spheroids: Relevance to Cancer Stem Cells and Clinical Applications. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, R.; Binda, E.; Orfanelli, U.; Cipelletti, B.; Gritti, A.; De Vitis, S.; Fiocco, R.; Foroni, C.; Dimeco, F.; Vescovi, A. Isolation and Characterization of Tumorigenic, Stem-like Neural Precursors from Human Glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 8130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Crisafulli, L.; Caldera, V.; Tortoreto, M.; Brilli, E.; Conforti, P.; Zunino, F.; Magrassi, L.; Schiffer, D.; Cattaneo, E. REST Controls Self-Renewal and Tumorigenic Competence of Human Glioblastoma Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Martinez, I.; Nivet, E.; Xia, Y.; Hishida, T.; Aguirre, A.; Ocampo, A.; Ma, L.; Morey, R.; Krause, M.N.; Zembrzycki, A.; et al. Establishment of Human IPSC-Based Models for the Study and Targeting of Glioma Initiating Cells. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagó, J.R.; Alfonso-Pecchio, A.; Okolie, O.; Dumitru, R.; Rinkenbaugh, A.; Baldwin, A.S.; Miller, C.R.; Magness, S.T.; Hingtgen, S.D. Therapeutically Engineered Induced Neural Stem Cells Are Tumour-Homing and Inhibit Progression of Glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merz, F.; Gaunitz, F.; Dehghani, F.; Renner, C.; Meixensberger, J.; Gutenberg, A.; Giese, A.; Schopow, K.; Hellwig, C.; Schäfer, M.; et al. Organotypic Slice Cultures of Human Glioblastoma Reveal Different Susceptibilities to Treatments. Neuro Oncol. 2013, 15, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnishi, T.; Matsumura, H.; Izumoto, S.; Hiraga, S.; Hayakawa, T. A Novel Model of Glioma Cell Invasion Using Organotypic Brain Slice Culture. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 2935–2940. [Google Scholar]

- Eisemann, T.; Costa, B.; Strelau, J.; Mittelbronn, M.; Angel, P.; Peterziel, H. An Advanced Glioma Cell Invasion Assay Based on Organotypic Brain Slice Cultures. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrik Heiland, D.; Ravi, V.M.; Behringer, S.P.; Frenking, J.H.; Wurm, J.; Joseph, K.; Garrelfs, N.W.C.; Strähle, J.; Heynckes, S.; Grauvogel, J.; et al. Tumor-Associated Reactive Astrocytes Aid the Evolution of Immunosuppressive Environment in Glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, V.M.; Joseph, K.; Wurm, J.; Behringer, S.; Garrelfs, N.; d’Errico, P.; Naseri, Y.; Franco, P.; Meyer-Luehmann, M.; Sankowski, R.; et al. Human Organotypic Brain Slice Culture: A Novel Framework for Environmental Research in Neuro-Oncology. Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2, e201900305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccellato, C.; Rehm, M. Glioblastoma, from Disease Understanding towards Optimal Cell-Based in Vitro Models. Cell. Oncol. 2022, 45, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuwatfa, W.H.; Pitt, W.G.; Husseini, G.A. Scaffold-Based 3D Cell Culture Models in Cancer Research. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 31, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witt Hamer, P.C.; Van Tilborg, A.A.G.; Eijk, P.P.; Sminia, P.; Troost, D.; Van Noorden, C.J.F.; Ylstra, B.; Leenstra, S. The Genomic Profile of Human Malignant Glioma Is Altered Early in Primary Cell Culture and Preserved in Spheroids. Oncogene 2008, 27, 2091–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.C.; Edwards, N.S.; Yates, J.D. Spheroids and Cell Survival. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2000, 36, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunti, S.; Hoke, A.T.K.; Vu, K.P.; London, N.R. Organoid and Spheroid Tumor Models: Techniques and Applications. Cancers 2021, 13, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, R.M.; McCredie, J.A.; Inch, W.R. Growth of Multicell Spheroids in Tissue Culture as a Model of Nodular Carcinomas2. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1971, 46, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slika, H.; Karimov, Z.; Alimonti, P.; Abou-Mrad, T.; De Fazio, E.; Alomari, S.; Tyler, B. Preclinical Models and Technologies in Glioblastoma Research: Evolution, Current State, and Future Avenues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, R.E.; Olive, P.L. Resistance of Tumor Cells to Chemo- and Radiotherapy Modulated by the Three-Dimensional Architecture of Solid Tumors and Spheroids. Methods Cell Biol. 2001, 64, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Seidel, C.; Ebner, R.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A. Spheroid-Based Drug Screen: Considerations and Practical Approach. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, F.; Beccaceci, G.; Fortuna, N.; Celotti, M.; De Felice, D.; Lorenzoni, M.; Foletto, V.; Genovesi, S.; Rubert, J.; Alaimo, A. The Organoid Era Permits the Development of New Applications to Study Glioblastoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Knoblich, J.A. Generation of Cerebral Organoids from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 2329–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, C.G.; Rivera, M.; Spangler, L.C.; Wu, Q.; Mack, S.C.; Prager, B.C.; Couce, M.; McLendon, R.E.; Sloan, A.E.; Rich, J.N. A Three-Dimensional Organoid Culture System Derived from Human Glioblastomas Recapitulates the Hypoxic Gradients and Cancer Stem Cell Heterogeneity of Tumors Found in Vivo. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2465–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, F.; Salinas, R.D.; Zhang, D.Y.; Nguyen, P.T.T.; Schnoll, J.G.; Wong, S.Z.H.; Thokala, R.; Sheikh, S.; Saxena, D.; Prokop, S.; et al. A Patient-Derived Glioblastoma Organoid Model and Biobank Recapitulates Inter- and Intra-Tumoral Heterogeneity. Cell 2020, 180, 188–204.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, J.; Pao, G.M.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Verma, I.M. Glioblastoma Model Using Human Cerebral Organoids. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishahak, M.; Han, R.H.; Annamalai, D.; Woodiwiss, T.; McCornack, C.; Cleary, R.T.; DeSouza, P.A.; Qu, X.; Dahiya, S.; Kim, A.H.; et al. Modeling Glioblastoma Tumor Progression via CRISPR-Engineered Brain Organoids. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarne, N.; D’Souza, R.C.J.; Palethorpe, H.M.; Bradbrook, K.A.; Gomez, G.A.; Day, B.W. Personalising Glioblastoma Medicine: Explant Organoid Applications, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, S.; Guo, P.; Liao, K.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, J.; Lin, S.; Yang, M.; Cai, G.; et al. Generation and Banking of Patient-Derived Glioblastoma Organoid and Its Application in Cancer Neuroscience. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2024, 14, 5000–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, D.; Park, H.C.; Park, M.; Zhang, S.; Na, O.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, M.; Ahn, S.; Chung, Y.J. Tumor Microenvironment-Preserving Gliosarcoma Organoids as an in Vitro Preclinical Platform: A Comparative Analysis with Glioblastoma Models. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logun, M.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Bagley, S.J.; Li, N.; Desai, A.; Zhang, D.Y.; Nasrallah, M.P.; Pai, E.L.L.; Oner, B.S.; et al. Patient-Derived Glioblastoma Organoids as Real-Time Avatars for Assessing Responses to Clinical CAR-T Cell Therapy. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 181–190.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linkous, A.; Balamatsias, D.; Snuderl, M.; Edwards, L.; Miyaguchi, K.; Milner, T.; Reich, B.; Cohen-Gould, L.; Storaska, A.; Nakayama, Y.; et al. Modeling Patient-Derived Glioblastoma with Cerebral Organoids. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 3203–3211.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pine, A.R.; Cirigliano, S.M.; Nicholson, J.G.; Hu, Y.; Linkous, A.; Miyaguchi, K.; Edwards, L.; Singhania, R.; Schwartz, T.H.; Ramakrishna, R.; et al. Tumor Microenvironment Is Critical for the Maintenance of Cellular States Found in Primary Glioblastomas. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 964–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weth, F.R.; Peng, L.; Paterson, E.; Tan, S.T.; Gray, C. Utility of the Cerebral Organoid Glioma ‘GLICO’ Model for Screening Applications. Cells 2023, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangena, V.; Chanoch-Myers, R.; Sartore, R.; Paulsen, B.; Gritsch, S.; Weisman, H.; Hara, T.; Breakefield, X.O.; Breyne, K.; Regev, A.; et al. Glioblastoma Cortical Organoids Recapitulate Cell-State Heterogeneity and Intercellular Transfer. Cancer Discov. 2025, 15, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, R.; Lee, W.; Kim, G.H.; Jeon, S.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, K.H.; Won, J.K.; Lee, W.; et al. Assembly of Glioblastoma Tumoroids and Cerebral Organoids: A 3D in Vitro Model for Tumor Cell Invasion. Mol. Oncol. 2025, 19, 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, J.M.; Overstreet, D.J.; Le, L.D.; Vernon, B.L.; Sirianni, R.W. Bioengineered Scaffolds for 3D Analysis of Glioblastoma Proliferation and Invasion. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 43, 1965–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, A.; Atala, A. Printing Technologies for Medical Applications. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, T.; Ranđelović, T.; Dragoj, M.; Stojković Burić, S.; Fernández, L.; Ochoa, I.; Pérez-García, V.M.; Pešić, M. In Vitro Biomimetic Models for Glioblastoma-a Promising Tool for Drug Response Studies. Drug Resist. Updat. 2021, 55, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orcheston-Findlay, L.; Bax, S.; Utama, R.; Engel, M.; Govender, D.; O’neill, G. Advanced Spheroid, Tumouroid and 3d Bioprinted in-Vitro Models of Adult and Paediatric Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.A.; Bansal, R.; Lammers, T.; Zhang, Y.S.; Michel Schiffelers, R.; Prakash, J. 3D-Bioprinted Mini-Brain: A Glioblastoma Model to Study Cellular Interactions and Therapeutics. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermida, M.A.; Kumar, J.D.; Schwarz, D.; Laverty, K.G.; Di Bartolo, A.; Ardron, M.; Bogomolnijs, M.; Clavreul, A.; Brennan, P.M.; Wiegand, U.K.; et al. Three Dimensional in Vitro Models of Cancer: Bioprinting Multilineage Glioblastoma Models. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2020, 75, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadwick, M.; Yang, C.; Liu, L.; Gamboa, C.M.; Jara, K.; Lee, H.; Sabaawy, H.E. Rapid Processing and Drug Evaluation in Glioblastoma Patient-Derived Organoid Models with 4D Bioprinted Arrays. iScience 2020, 23, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Agrawal, B.; Sun, D.; Kuo, J.S.; Williams, J.C. Microfluidics-Based Devices: New Tools for Studying Cancer and Cancer Stem Cell Migration. Biomicrofluidics 2011, 5, 13412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Agrawal, B.; Clark, P.A.; Williams, J.C.; Kuo, J.S. Evaluation of Cancer Stem Cell Migration Using Compartmentalizing Microfluidic Devices and Live Cell Imaging. J. Vis. Exp. 2011, 58, e3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedron, S.; Polishetty, H.; Pritchard, A.M.; Mahadik, B.P.; Sarkaria, J.N.; Harley, B.A.C. Spatially Graded Hydrogels for Preclinical Testing of Glioblastoma Anticancer Therapeutics. MRS Commun. 2017, 7, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wei, W.; Shen, L.; Sun, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, J. Engineered 3D Tumour Model for Study of Glioblastoma Aggressiveness and Drug Evaluation on a Detachably Assembled Microfluidic Device. Biomed. Microdevices 2018, 20, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logun, M.T.; Bisel, N.S.; Tanasse, E.A.; Zhao, W.; Gunasekera, B.; Mao, L.; Karumbaiah, L. Glioma Cell Invasion Is Significantly Enhanced in Composite Hydrogel Matrices Composed of Chondroitin 4- and 4,6-Sulfated Glycosaminoglycans. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 6052–6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, J.; Choi, H.; Lee, D.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.-H. Integration of Microfluidic Chip with Biomimetic Hydrogel for 3D Controlling and Monitoring of Cell Alignment and Migration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2014, 102, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Morales, R.-T.T.; Qian, W.; Wang, H.; Gagner, J.-P.; Dolgalev, I.; Placantonakis, D.; Zagzag, D.; Cimmino, L.; Snuderl, M.; et al. Hacking Macrophage-Associated Immunosuppression for Regulating Glioblastoma Angiogenesis. Biomaterials 2018, 161, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lin, H.; Rauch, J.; Deleyrolle, L.P.; Reynolds, B.A.; Viljoen, H.J.; Zhang, C.; Gu, L.; Van Wyk, E.; Lei, Y. Scalable Culturing of Primary Human Glioblastoma Tumor-Initiating Cells with a Cell-Friendly Culture System. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akay, M.; Hite, J.; Avci, N.G.; Fan, Y.; Akay, Y.; Lu, G.; Zhu, J.J. Drug Screening of Human GBM Spheroids in Brain Cancer Chip. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, W.J.; Kwon, K.-D.; Ha, K.-T.; Choi, B.T.; Lee, S.-Y.; Shin, H.K. Isolinderalactone Suppresses Human Glioblastoma Growth and Angiogenic Activity in 3D Microfluidic Chip and in Vivo Mouse Models. Cancer Lett. 2020, 478, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olubajo, F.; Achawal, S.; Greenman, J. Development of a Microfluidic Culture Paradigm for Ex Vivo Maintenance of Human Glioblastoma Tissue: A New Glioblastoma Model? Transl. Oncol. 2020, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Liu, X.; Bi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Antony, A.; Lee, D.Y.; Huntoon, K.; Jeong, S.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Adaptive Design of MRNA-Loaded Extracellular Vesicles for Targeted Immunotherapy of Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Prabhu, V.; Kumar, P.; Mani, N.K. Advancements in Microfluidic Platforms for Glioblastoma Research. Chemistry 2024, 6, 1039–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.-G.; Jeong, Y.H.; Kim, Y.; Choi, Y.-J.; Moon, H.E.; Park, S.H.; Kang, K.S.; Bae, M.; Jang, J.; Youn, H.; et al. A Bioprinted Human-Glioblastoma-on-a-Chip for the Identification of Patient-Specific Responses to Chemoradiotherapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, D.; Fiorelli, R.; Barrientos, E.S.; Melendez, E.L.; Sanai, N.; Mehta, S.; Nikkhah, M. A Three-Dimensional (3D) Organotypic Microfluidic Model for Glioma Stem Cells—Vascular Interactions. Biomaterials 2019, 198, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.S.; Lee, V.K.; Zou, H.; Friedel, R.H.; Intes, X.; Dai, G. High-Resolution Tomographic Analysis of in Vitro 3D Glioblastoma Tumor Model under Long-Term Drug Treatment. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePalma, T.; Rodriguez, M.; Kollin, L.; Hughes, K.; Jones, K.; Stagner, E.; Venere, M.; Skardal, A. A Microfluidic Blood Brain Barrier Model to Study the Influence of Glioblastoma Tumor Cells on BBB Function. Small 2025, 21, e2411361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straehla, J.P.; Hajal, C.; Safford, H.C.; Offeddu, G.S. A Predictive Microfluidic Model of Human Glioblastoma to Assess Trafficking of Blood–Brain Barrier-Penetrant Nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2118697119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayona, C.; Olaizola-Rodrigo, C.; Sharko, V.; Ashrafi, M.; Barrio, J.D.; Doblaré, M.; Monge, R.; Ochoa, I.; Oliván, S. A Novel Multicompartment Barrier-Free Microfluidic Device Reveals the Impact of Extracellular Matrix Stiffening and Temozolomide on Immune-Tumor Interactions in Glioblastoma. Small 2025, 21, e2409229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Bhuyan, T.; Jewell, C.; Kawakita, S.; Sharma, S.; Nguyen, H.T.; Hassani Najafabadi, A.; Ermis, M.; Falcone, N.; Chen, J.; et al. Recent Developments in Glioblastoma-On-A-Chip for Advanced Drug Screening Applications. Small 2025, 21, e2405511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, B.L.; Pokorny, J.L.; Schroeder, M.A.; Sarkaria, J.N. Establishment, Maintenance and in Vitro and in Vivo Applications of Primary Human Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) Xenograft Models for Translational Biology Studies and Drug Discovery. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2011, 52, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, N.; Fernández, V.; Pereira, R.C.; Rancati, S.; Pelizzoli, R.; De Pietri Tonelli, D. A Xenotransplant Model of Human Brain Tumors in Wild-Type Mice. iScience 2020, 23, 100813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrizii, M.; Bartucci, M.; Pine, S.R.; Sabaawy, H.E. Utility of Glioblastoma Patient-Derived Orthotopic Xenografts in Drug Discovery and Personalized Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, K.M.; Kim, J.; Jin, J.; Kim, M.; Seol, H.J.; Muradov, J.; Yang, H.; Choi, Y.L.; Park, W.Y.; Kong, D.S.; et al. Patient-Specific Orthotopic Glioblastoma Xenograft Models Recapitulate the Histopathology and Biology of Human Glioblastomas In Situ. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.; Labani-Motlagh, A.; Chen, A.; Bohorquez, J.A.; Qin, B.; Dodda, M.; Yang, F.; Ansari, D.; Patel, S.; Ji, H.; et al. Development of a Human Glioblastoma Model Using Humanized DRAG Mice for Immunotherapy. Antib. Ther. 2023, 6, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, C.; Dubois, G.G.; Xavier, L.L.; Geraldo, H.H.; da Fonseca, C.C.C.; Correia, H.H.; Meirelles, F.; Ventura, G.; Romão, L.; Canedo, S.H.S.; et al. The Orthotopic Xenotransplant of Human Glioblastoma Successfully Recapitulates Glioblastoma-Microenvironment Interactions in a Non-Immunosuppressed Mouse Model. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdor, R.; García-Bernal, D.; Bueno, C.; Ródenas, M.; Moraleda, J.M.; Macian, F.; Martínez, S. Glioblastoma Progression Is Assisted by Induction of Immunosuppressive Function of Pericytes through Interaction with Tumor Cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 68614–68626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittori, M.; Motaln, H.; Turnšek, T.L. The Study of Glioma by Xenotransplantation in Zebrafish Early Life Stages. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2015, 63, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Patron, L.A.; Agudelo-Dueñãs, N.; Madrid-Wolff, J.; Venegas, J.A.; González, J.M.; Forero-Shelton, M.; Akle, V. Xenotransplantation of Human Glioblastoma in Zebrafish Larvae: In Vivo Imaging and Proliferation Assessment. Biol. Open 2019, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pliakopanou, A.; Antonopoulos, I.; Darzenta, N.; Serifi, I.; Simos, Y.V.; Katsenos, A.P.; Bellos, S.; Alexiou, G.A.; Kyritsis, A.P.; Leonardos, I.; et al. Glioblastoma Research on Zebrafish Xenograft Models: A Systematic Review. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, G.A.; Fu, W.; Kao, G.D. Temozolomide-Mediated Radiosensitization of Human Glioma Cells in a Zebrafish Embryonic System. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 3396–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, B.E.; Geiger, G.A.; Kridel, S.; Arcury-Quandt, A.E.; Robbins, M.E.; Kock, N.D.; Wheeler, K.; Peddi, P.; Georgakilas, A.; Kao, G.D.; et al. Identification and Biological Evaluation of a Novel and Potent Small Molecule Radiation Sensitizer via an Unbiased Screen of a Chemical Library. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8791–8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, S.; La Du, J.; Tanguay, R.L.; Greenwood, J.A. Calpain 2 Is Required for the Invasion of Glioblastoma Cells in the Zebrafish Brain Microenvironment. J. Neurosci. Res. 2012, 90, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampazzo, E.; Persano, L.; Pistollato, F.; Moro, E.; Frasson, C.; Porazzi, P.; Della Puppa, A.; Bresolin, S.; Battilana, G.; Indraccolo, S.; et al. Wnt Activation Promotes Neuronal Differentiation of Glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welker, A.M.; Jaros, B.D.; Puduvalli, V.K.; Imitola, J.; Kaur, B.; Beattie, C.E. Correction: Standardized Orthotopic Xenografts in Zebrafish Reveal Glioma Cell-Line-Specific Characteristics and Tumor Cell Heterogeneity. DMM Dis. Model. Mech. 2016, 9, 1063–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudelko, L.; Edwards, S.; Balan, M.; Nyqvist, D.; Al-Saadi, J.; Dittmer, J.; Almlöf, I.; Helleday, T.; Bräutigam, L. An Orthotopic Glioblastoma Animal Model Suitable for High-Throughput Screenings. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 1475–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morad, G.; Carman, C.V.; Hagedorn, E.J.; Perlin, J.R.; Zon, L.I.; Mustafaoglu, N.; Park, T.E.; Ingber, D.E.; Daisy, C.C.; Moses, M.A. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Breach the Intact Blood-Brain Barrier via Transcytosis. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 13853–13865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Ye, T.; Cao, D.; Huang, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Xie, Y.; Yao, S.; Zhao, C. Identify a Blood-Brain Barrier Penetrating Drug-TNB Using Zebrafish Orthotopic Glioblastoma Xenograft Model. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, V.M.; Will, P.; Kueckelhaus, J.; Sun, N.; Joseph, K.; Salié, H.; Vollmer, L.; Kuliesiute, U.; von Ehr, J.; Benotmane, J.K.; et al. Spatially Resolved Multi-Omics Deciphers Bidirectional Tumor-Host Interdependence in Glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 639–655.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.H.; Nucci, M.P.; Mamani, J.B.; Valle, N.M.E.; Ribeiro, E.F.; Rego, G.N.A.; Oliveira, F.A.; Theinel, M.H.; Santos, R.S.; Gamarra, L.F. The Advances in Glioblastoma On-a-Chip for Therapy Approaches. Cancers 2022, 14, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K.R.; Rockne, R.C.; Claridge, J.; Chaplain, M.A.; Alvord, E.C.; Anderson, A.R.A. Quantifying the Role of Angiogenesis in Malignant Progression of Gliomas: In Silico Modeling Integrates Imaging and Histology. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 7366–7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakkalis, V.; Sfakianakis, S.; Tzamali, E.; Marias, K.; Stamatakos, G.; Misichroni, F.; Ouzounoglou, E.; Kolokotroni, E.; Dionysiou, D.; Johnson, D.; et al. Web-Based Workflow Planning Platform Supporting the Design and Execution of Complex Multiscale Cancer Models. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2014, 18, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankeelov, T.E.; Atuegwu, N.; Hormuth, D.; Weis, J.A.; Barnes, S.L.; Miga, M.I.; Rericha, E.C.; Quaranta, V. Clinically Relevant Modeling of Tumor Growth and Treatment Response. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 187ps9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düchting, W.; Ulmer, W.; Lehrig, R.; Ginsberg, T.; Dedeleit, E. Computer Simulation and Modelling of Tumor Spheroid Growth and Their Relevance for Optimization of Fractionated Radiotherapy. Strahlenther. Onkol. 1992, 168, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Falco, J.; Agosti, A.; Vetrano, I.G.; Bizzi, A.; Restelli, F.; Broggi, M.; Schiariti, M.; Dimeco, F.; Ferroli, P.; Ciarletta, P.; et al. In Silico Mathematical Modelling for Glioblastoma: A Critical Review and a Patient-Specific Case. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K.R.; Alvord, J.; Murray, J.D. A Quantitative Model for Differential Motility of Gliomas in Grey and White Matter. Cell Prolif. 2000, 33, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K.R.; Alvord, E.C.; Murray, J.D. Virtual Brain Tumours (Gliomas) Enhance the Reality of Medical Imaging and Highlight Inadequacies of Current Therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2002, 86, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Torquato, S. Emergent Behaviors from a Cellular Automaton Model for Invasive Tumor Growth in Heterogeneous Microenvironments. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, J.C.L.; Talkenberger, K.; Seifert, M.; Klink, B.; Hawkins-Daarud, A.; Swanson, K.R.; Hatzikirou, H.; Deutsch, A. The Biology and Mathematical Modelling of Glioma Invasion: A Review. J. R. Soc. Interface 2017, 14, 20170490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafallah, A.M.; Huq, S.; Jimenez, A.E.; Serra, R.; Bettegowda, C.; Mukherjee, D. “Zooming in” on Glioblastoma: Understanding Tumor Heterogeneity and Its Clinical Implications in the Era of Single-Cell Ribonucleic Acid Sequencing. Neurosurgery 2021, 88, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieboes, H.B.; Jin, F.; Chuang, Y.-L.; Wise, S.M.; Lowengrub, J.S.; Cristini, V. Three-Dimensional Multispecies Nonlinear Tumor Growth-II: Tumor Invasion and Angiogenesis. J. Theor. Biol. 2010, 264, 1254–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuaje, F. Computational Models for Predicting Drug Responses in Cancer Research. Brief. Bioinform. 2017, 18, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, N.; Singh, P.; Kumar, A. A Multistep In Silico Approach Identifies Potential Glioblastoma Drug Candidates via Inclusive Molecular Targeting of Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 9253–9271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Nguyen, L.X.T.; Li, L.; Zhao, D.; Kumar, B.; Wu, H.; Lin, A.; Pellicano, F.; Hopcroft, L.; Su, Y.L.; et al. Bone Marrow Niche Trafficking of MiR-126 Controls the Self-Renewal of Leukemia Stem Cells in Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lawler, S.; Nowicki, M.O.; Chiocca, E.A.; Friedman, A. A Mathematical Model for Pattern Formation of Glioma Cells Outside the Tumor Spheroid Core. J. Theor. Biol. 2009, 260, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Zhao, R.; Haeno, H.; Vivanco, I.; Michor, F. Mathematical Modeling Identifies Optimum Lapatinib Dosing Schedules for the Treatment of Glioblastoma Patients. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabé, M.; Dumont, S.; Álvarez-Arenas, A.; Janati, H.; Belmonte-Beitia, J.; Calvo, G.F.; Thibault-Carpentier, C.; Séry, Q.; Chauvin, C.; Joalland, N.; et al. Identification of a Transient State during the Acquisition of Temozolomide Resistance in Glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraiopoulou, M.E.; Tzamali, E.; Tzedakis, G.; Liapis, E.; Zacharakis, G.; Vakis, A.; Papamatheakis, J.; Sakkalis, V. Integrating in Vitro Experiments with in Silico Approaches for Glioblastoma Invasion: The Role of Cell-to-Cell Adhesion Heterogeneity. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-García, V.M.; Calvo, G.F.; Bosque, J.J.; León-Triana, O.; Jiménez, J.; Pérez-Beteta, J.; Belmonte-Beitia, J.; Valiente, M.; Zhu, L.; García-Gómez, P.; et al. Universal Scaling Laws Rule Explosive Growth in Human Cancers. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayensa-Jiménez, J.; Pérez-Aliacar, M.; Doweidar, M.H.; Gaffney, E.A.; Doblaré, M. An Overview from Physically-Based to Data-Driven Approaches of the Modelling and Simulation of Glioblastoma Progression in Microfluidic Devices; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2025; ISBN 1183102510291. [Google Scholar]

- Bongiovanni, A.; Colotti, G.; Liguori, G.L.; Di Carlo, M.; Digilio, F.A.; Lacerra, G.; Mascia, A.; Cirafici, A.M.; Barra, A.; Lanati, A.; et al. Applying Quality and Project Management Methodologies in Biomedical Research Laboratories: A Public Research Network’s Case Study. Accredit. Qual. Assur. 2015, 20, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digilio, F.A.; Lanati, A.; Bongiovanni, A.; Mascia, A.; Di Carlo, M.; Barra, A.; Cirafici, A.M.; Colotti, G.; Kisslinger, A.; Lacerra, G.; et al. Quality-Based Model for Life Sciences Research Guidelines. Accredit. Qual. Assur. 2016, 21, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciotto, S.; Barone, M.E.; Fierli, D.; Aranyos, A.; Adamo, G.; Božič, D.; Romancino, D.P.; Stanly, C.; Parkes, R.; Morsbach, S.; et al. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles from Microalgae: Towards the Production of Sustainable and Natural Nanocarriers of Bioactive Compounds. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 2917–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loria, F.; Picciotto, S.; Adamo, G.; Zendrini, A.; Raccosta, S.; Manno, M.; Bergese, P.; Liguori, G.L.; Bongiovanni, A.; Zarovni, N. A decision-making tool for navigating extracellular vesicle research and product development. JEV 2024, 13, e70021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphyllou, E.; Shu, B.; Sanchez, S.N.; Ray, T. Multi-Criteria Decision Making: An Operations Research Approach. Encycl. Electr. Electron. Eng. 1998, 15, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann, S.; Regierer, B.; D’Elia, D.; Kisslinger, A.; Liguori, G.L. Toward the Definition of Common Strategies for Improving Reproducibility, Standardization, Management, and Overall Impact of Academic Research. Adv. Biomembr. Lipid Self-Assembly 2022, 35, 2–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, R.; Judicone, C.; Mooberry, M.; Boucekine, M.; Key, N.S.; Dignat-George, F.; Ambrozic, A.; Bailly, N.; Buffat, C.; Buzas, E.; et al. Standardization of Pre-Analytical Variables in Plasma Microparticle Determination: Results of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis SSC Collaborative Workshop. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV2023): From Basic to Advanced Approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2023, 12, e12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustin, S.A.; Beaulieu, J.F.; Huggett, J.; Jaggi, R.; Kibenge, F.S.B.; Olsvik, P.A.; Penning, L.C.; Toegel, S. MIQE Précis: Practical Implementation of Minimum Standard Guidelines for Fluorescence-Based Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. BMC Mol. Biol. 2010, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forry, S.; Hubbard, L.; Espey, M.G.; Vikram, B.; Mann, B.; Tawab-Amiri, A.; Hecht, T. The NCI Glioblastoma Therapeutics Network (GTN). Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Origin | Mouse vs. Rat | Model Type | Generation | Effort | Representativity Respect to Patient GB | Complexity | Purpose | Throughput | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | Time | ECM | TME | BBB | Applications | ||||||

| Rat | Strengths (i) Larger brain size facilitating stereotactic implantation (ii) Larger tumor size improving in vivo imaging and allowing higher drug dose administration | Chemically induced mutants | Mutagen injections | H | Variable from few to several weeks | Variable Different tumor mechanisms and brain architecture | + | + | + | Response to different therapies; Immune mechanisms | L |

| Cell lines | Derived from in vivo mutants | L | Weeks | L/M Can differ from patient GB both genetically and phenotypically; Accumulate genetic mutations in culture | - | - | - | Cancer cell features; Response to therapy | H | ||

| Weaknesses (i) Cannot be easily genetically manipulated (ii) More expensive to purchase and maintain (iii) Minor availability of specific reagents | |||||||||||

| Syngeneic grafts | Intracranial or intravenous injection of cell lines | M | Variable from few to several weeks | Variable Different tumor mechanisms and brain architecture; Depending also on transplanted cell features | + | + | + | Response to therapies; Immune mechanisms | M | ||

| Mouse | Strengths (i) Possibility to be genetically manipulated to harbor specific mutations (ii) Smaller and easier to maintain (iii) Major availability for specific reagents | Chemically induced mutants | Mutagen injections | M/H | Variable from few to several weeks | Variable Different tumor mechanisms and brain architecture | + | + | + | Response to different therapies; Immune mechanisms | L |

| Genetically engineered mutants | Cre/loxP | M/H | 10–14 months | Variable Different tumor mechanisms and brain architecture; Carrying selected targeted mutations by origin cannot replicate the GB heterogeneity | + | + | + | Cancer Biology; Effect of specific gene mutation; Response to therapy; Immune mechanisms | L/M | ||

| Transposon induced | 6–8 months | ||||||||||

| Weaknesses (i) Smaller animal size complicating stereotactic procedures (ii) Smaller tumor size complicating in vivo imaging and treatment evaluation | CRISPR/ Cas9 | 5–7 months | |||||||||

| Engineered virus induced | Weeks | ||||||||||

| Cell lines | Derived from in vivo mutants | L | weeks | L/M Can differ from patient GB both genetically and phenotypically; Accumulate genetic mutations in culture | - | - | - | Cancer cell features; Response to therapy | H | ||

| Syngeneic Grafts | Intracranial or intravenous injection of cell lines | M | Variable from few to several weeks | Variable Different tumor mechanisms and brain architecture; Depending also on transplanted cell features | + | + | + | Response to different therapies; Immune mechanisms | M | ||

| Modeling Strategy | Generation | Strengths | Weaknesses | Purpose/Applications | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP/D | CM/I | DA | RT | TME | BBB | T | |||||

| 2D | Monolayer Culture | Culture of adherent cells in medium with serum and nutrients | Easy; Cost effective; High availability of standardized protocols and commercial reagents | Subject to genetic drift; Not reproducing the spatial complexity and intricate cell relationships of in vivo GB | + | + | + | + | H | ||

| 3D | Spheroid | Spontaneous aggregation in suspension | |||||||||

| -MCTS | Mainly GB cell lines | Easy to culture and genetically manipulate | Low histological similarity to in vivo GB | + | + | + | + | M/H | |||

| -Gliomasphere | GB primary cells | Representing genetic and phenotypic in vivo GB heterogeneity; Suitable for personalized medicine | Low architecture complexity respect to in vivo GB | + | + | + | + | L/M | |||

| -OMS | Tumor and not tumor primary cells | More similar to in vivo GB; Reproducing TME; Suitable for personalized medicine | Low architecture complexity respect to in vivo GB | + | + | + | + | + | L/M | ||

| GB Organoid | Free self-assembly of GB primary cells | High complexity; Representing heterogeneity of in vivo GB; Suitable for personalized medicine; Versatile and customizable | Low control and reproducibility | + | + | + | + | +/- | M | ||

| GLICO | Incorporation of primary GSCs into brain organoids | High correlation with in vivo GB; Reproducing interaction with TME; Suitable for personalized medicine | High cost, Low control | + | + | + | + | L | |||

| Scaffold | Embedding and growth of primary GB cells on defined scaffolds | Representing heterogeneity of in vivo GB; Reproducible; Suitable for personalized medicine | Scaffold biocompatibility | + | + | + | + | M | |||

| Bioprinting | Combination of GB cells (and eventually TME cells) in a bioreactor with a bioink | Highly controlled; Reproducible; Depending on the types of bioprinted cells can highly represent GB complexity and TME | High cost; High specialization; Need of suitable bioinks to mimic TME complexity | + | + | + | + | +/- | +/- | M | |

| Microfluidic | Very small volumes of cells and fluids are combined for perfusion culturing | Low amounts of cells and materials; Reproducible; Dynamic environments closer resembling in vivo GB; Depending on the types of cells can highly represent GB complexity and TME | High cost and specialization; Need of performant materials to build the devices; Challenging downstream sample analysis | + | + | + | + | +/- | +/- | M/H | |

| GB-on-a-chip | Integration of different technologies in a chip | Controlled; Reproducible; Highly resembling in vivo GB; Suitable for personalized medicine | High cost and specialization; Need of performant materials to build the devices; Challenging downstream sample analysis | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | M | |

| In vivo | Mouse xenograft | Injection of GB cells (cell lines, GPDCs or GB tumor pieces) | L/M | ||||||||

| -Heterotopic | Intravenous | Simple; High efficiency | High costs of housing for immunodeficient mice; Different tumor environment | + | + | + | L/M | ||||

| -Orthotopic | Intracranial | Representative of the in vivo physiological TME | High costs of housing for immunodeficient mice; Complex; High mortality | + | + | + | + | + | L/M | ||

| Zebrafish xenograft | Injection of GB cells (cell lines, GPDCs or GB tumor pieces) | M/H | |||||||||

| -Heterotopic | Intra yolk sac | Simple; High efficiency; Low cost of housing; Transparency; In vivo imaging | Different tumor environment | + | + | + | M/H | ||||

| -Orthotopic | Intracranial or into the blastula (injected cells incorporate into the brain) | Low cost of housing; Representative of the in vivo physiological TME; In vivo imaging; Transparency | Complex | + | + | + | + | + | + | M | |

| In silico | Discrete Model | Simulation at single cell level | Can accurately describe the behavior of single cells in simpler contexts | Need of experimental data to create, validate and optimize the model | + | + | + | M/H | |||

| Continuum Model | Simulation at tissue level | Can accurately describe patient GB | + | + | + | + | + | M/H | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Antonio, C.; Liguori, G.L. Modeling Glioblastoma for Translation: Strengths and Pitfalls of Preclinical Studies. Biology 2025, 14, 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111490

D’Antonio C, Liguori GL. Modeling Glioblastoma for Translation: Strengths and Pitfalls of Preclinical Studies. Biology. 2025; 14(11):1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111490

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Antonio, Concetta, and Giovanna L. Liguori. 2025. "Modeling Glioblastoma for Translation: Strengths and Pitfalls of Preclinical Studies" Biology 14, no. 11: 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111490

APA StyleD’Antonio, C., & Liguori, G. L. (2025). Modeling Glioblastoma for Translation: Strengths and Pitfalls of Preclinical Studies. Biology, 14(11), 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14111490