Preclinical Models of Donation-After-Circulatory-Death and Brain-Death: Advances in Kidney Preservation and Transplantation

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Need for Renal Grafts from Deceased Donors

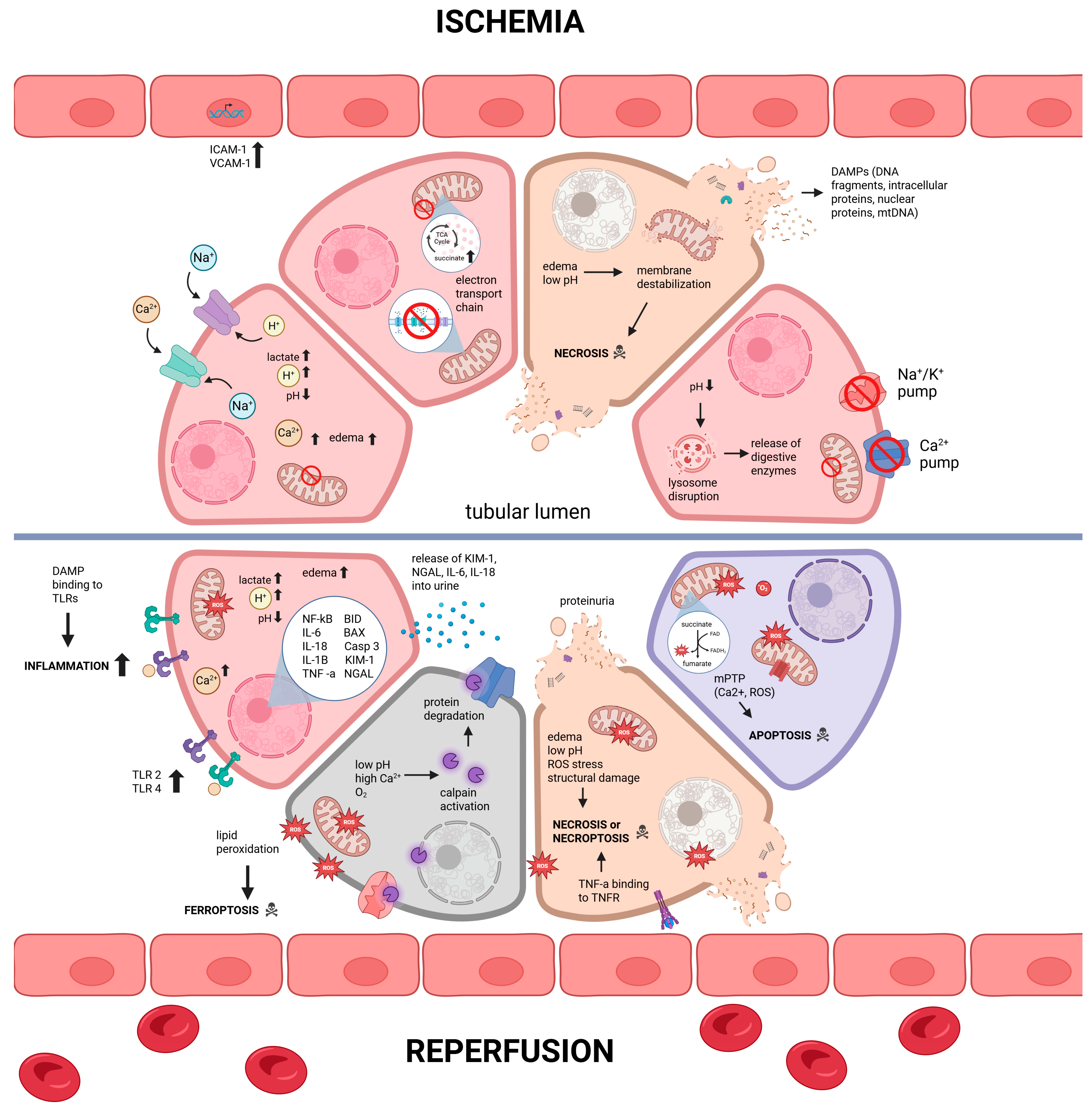

2. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Damage in Deceased Donor Kidneys

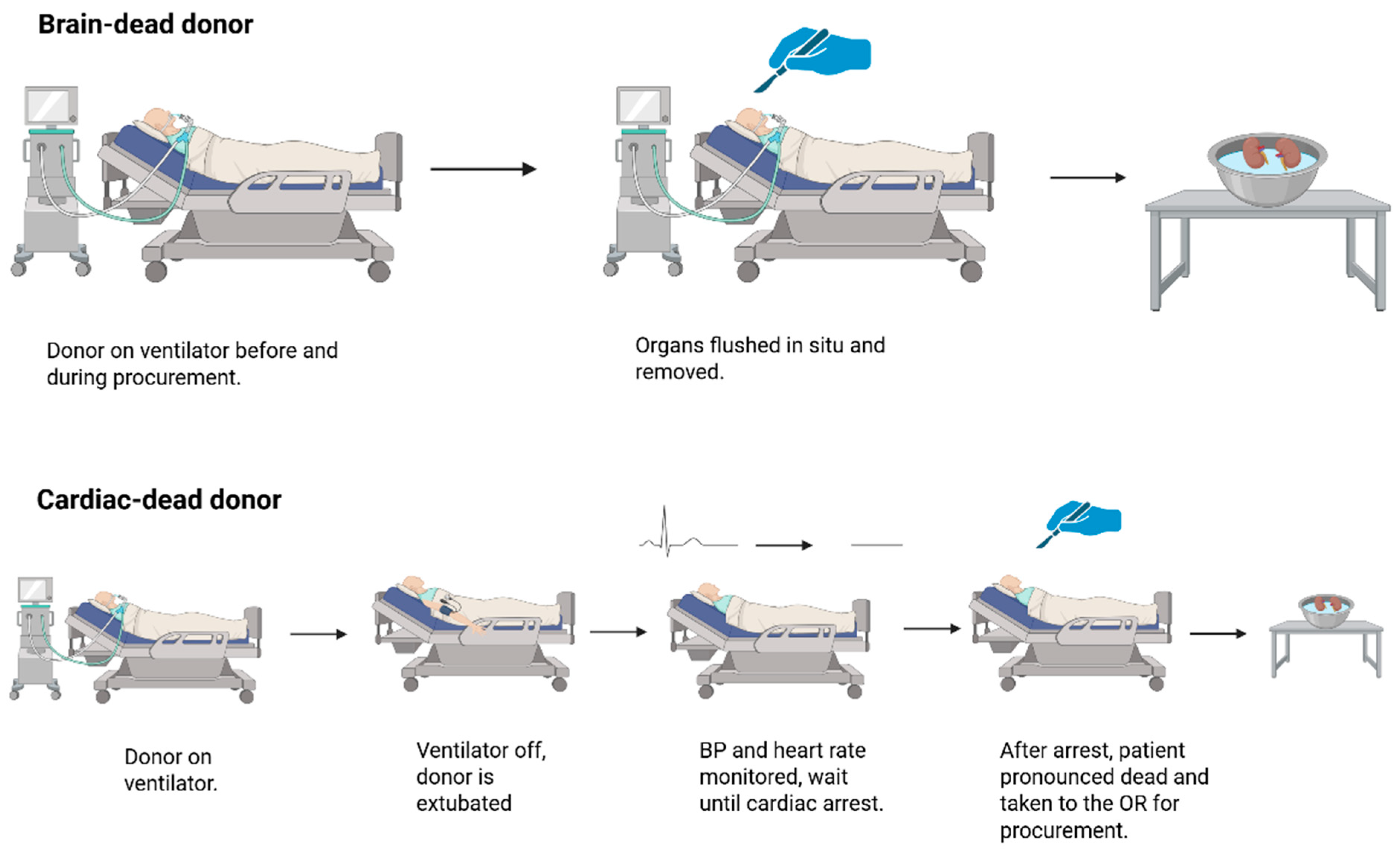

2.1. Renal Grafts from Donation-After-Cardiac-Death

2.2. Renal Grafts from Donation-After-Brain-Death

2.3. Animal Models of Donation-After-Brain-Death

3. Animal Models of Preservation of Renal Grafts from Deceased Donors

3.1. Historical Account of Static Cold Storage of Renal Grafts

3.2. Renal Graft Preservation Time: Lessons from Animal Models

3.3. Machine Perfusion as an Alternative to Static Cold Storage

3.4. Animal Models That Studied Normothermic Machine Perfusion (NMP)

3.5. Animal Models That Studied Oxygenated Perfusion of Renal Grafts and Cell Death

4. Animal Models to Study Therapeutics for Deceased Donor Kidneys

4.1. Animal Models That Studied Supplements to Storage Solutions of Deceased Donor Kidneys

4.2. Animal Studies That Evaluated Donor Strategies

5. Considerations and Limitations of Animal Models of Kidney Transplantation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: An update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdeshwar, H.N.; Anjum, F. Hemodialysis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563296 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Ahbap, E. Factors associated with long-term survival in maintenance hemodialysis patients: A 5-year prospective follow-up study. SiSli Etfal Hastan Tip Bull. Med. Bull. Sisli Hosp. 2022, 56, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.S.; Ojo, A. The Alphabet Soup of Kidney Transplantation: SCD, DCD, ECD—Fundamentals for the Practicing Nephrologist. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 1827–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmer, A.; Rohrer, M.L.; Benden, C.; Krügel, N.; Beyeler, F.; Immer, F.F. Organ donation after circulatory death as compared with organ donation after brain death in Switzerland—An observational study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2022, 152, w30132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugbartey, G.J. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of cell damage and cell death in ischemia-reperfusion injury in organ transplantation. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijs-Moeke, G.J.; Pischke, S.E.; Berger, S.P.; Sanders, J.S.F.; Pol, R.A.; Struys, M.M.R.F.; Ploeg, R.J.; Leuvenink, H.G.D. Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury in Kidney Transplantation: Relevant Mechanisms in Injury and Repair. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, M.; Rosso, G.; Bertoni, E. Update on ischemia-reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation: Pathogenesis and treatment. World J. Transplant. 2015, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Pell, V.R.; Gaude, E.; Aksentijević, D.; Sundier, S.Y.; Robb, E.L.; Logan, A.; Nadtochiy, S.M.; Ord, E.N.J.; Smith, A.C.; et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 2014, 515, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Yuan, C.; Wu, X. Targeting ferroptosis in acute kidney injury. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid Peroxidation: Production, Metabolism, and Signaling Mechanisms of Malondialdehyde and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Filburn, C.R.; Klotz, L.O.; Zweier, J.L.; Sollott, S.J. Reactive Oxygen Species (Ros-Induced) Ros Release. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1001–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaseva, A.V.; Marchenko, N.D.; Ji, K.; Tsirka, S.E.; Holzmann, S.; Moll, U.M. p53 Opens the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore to Trigger Necrosis. Cell 2012, 149, 1536–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granger, D.N.; Kvietys, P.R. Reperfusion injury and reactive oxygen species: The evolution of a concept. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 524–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jevnikar, A.M.; Brennan, D.C.; Singer, G.G.; Heng, J.E.; Maslinski, W.; Wuthrich, R.P.; Glimcher, L.H.; Kelley, V.E. Stimulated kidney tubular epithelial cells express membrane associated and secreted TNFα. Kidney Int. 1991, 40, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugbartey, G.J. Nitric oxide in kidney transplantation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghe, T.V.; Linkermann, A.; Jouan-Lanhouet, S.; Walczak, H.; Vandenabeele, P. Regulated necrosis: The expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-Sancho, J.; Villarreal, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.X.; Liu, Y.; Tullius, S.G.; García-Cardeña, G. Flow cessation triggers endothelial dysfunction during organ cold storage conditions: Strategies for pharmacologic intervention. Transplantation 2010, 90, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, M.D.; Lehr, H.A.; Messmer, K. Role of oxygen radicals in the microcirculatory manifestations of postischemic injury. Klin. Wochenschr. 1991, 69, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezkalla, S.H.; Kloner, R.A. No-Reflow Phenomenon. Circulation 2002, 105, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Lim, S.W.; Li, C.; Kim, J.S.; Sun, B.K.; Ahn, K.O.; Han, S.W.; Kim, J.; Yang, C.W. Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Activates Innate Immunity in Rat Kidneys. Transplantation 2005, 79, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slegtenhorst, B.R.; Dor, F.J.M.F.; Rodriguez, H.; Voskuil, F.J.; Tullius, S.G. Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury and its Consequences on Immunity and Inflammation. Curr. Transplant. Rep. 2014, 1, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, H.J. Of Inflammasomes and Alarmins: IL-1β and IL-1α in Kidney Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 2564–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Gamboni-Robertson, F.; He, Q.; Svetkauskaite, D.; Kim, J.Y.; Strassheim, D.; Sohn, J.W.; Yamada, S.; Maruyama, I.; Banerjee, A.; et al. High mobility group box 1 protein interacts with multiple Toll-like receptors. Am. J. Physiol-Cell Physiol. 2006, 290, C917–C924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Liu, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, F. NLRP3 inflammasome: A potential therapeutic target to minimize renal ischemia/reperfusion injury during transplantation. Transpl. Immunol. 2022, 75, 101718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.M.; Arulkumaran, N.; Singer, M.; Unwin, R.J.; Tam, F.W. Is the inflammasome a potential therapeutic target in renal disease? BMC Nephrol. 2014, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfs, T.G.A.M.; Buurman, W.A.; Van Schadewijk, A.; de Vries, B.; Daemen, M.A.; Hiemstra, P.S.; van’t Veer, C. In Vivo Expression of Toll-Like Receptor 2 and 4 by Renal Epithelial Cells: IFN-γ and TNF-α Mediated Up-Regulation During Inflammation. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 1286–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanellis, P.; Mazilescu, L.; Kollmann, D.; Linares-Cervantes, I.; Kaths, J.M.; Ganesh, S.; Oquendo, F.; Sharma, M.; Goto, T.; Noguchi, Y.; et al. Prolonged warm ischemia time leads to severe renal dysfunction of donation-after-cardiac death kidney grafts. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.T.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Yu, M.; Daniel, E.; Sandra, V.; Sanichar, N.; King, K.L.; Stevens, J.S.; Husain, S.A.; Mohan, S. Effects of Delayed Graft Function on Transplant Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. Transplant. Direct. 2023, 9, e1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugbartey, G.J. Physiological role of hydrogen sulfide in the kidney and its therapeutic implications for kidney diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023, 166, 115396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarlagadda, S.G.; Coca, S.G.; Garg, A.X.; Doshi, M.; Poggio, E.; Marcus, R.J.; Parikh, C.R. Marked variation in the definition and diagnosis of delayed graft function: A systematic review. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 2995–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.; Sandoval, P.R.; Husain, S.A.; King, K.L.; Dube, G.K.; Tsapepas, D.; Mohan, S.; Ratner, L.E. Impact of warm ischemia time on outcomes for kidneys donated after cardiac death Post-KAS. Clin. Transplant. 2020, 34, e14040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennankore, K.K.; Kim, S.J.; Alwayn, I.P.J.; Kiberd, B.A. Prolonged warm ischemia time is associated with graft failure and mortality after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuong, M.; Ruiz, A.; Evrard, P.; Kuiper, M.; Boffa, C.; Akhtar, M.Z.; Neuberger, J.; Ploeg, R. New classification of donation after circulatory death donors definitions and terminology. Transpl. Int. 2016, 29, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Jung, E.S.; Oh, J.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, J.M. Organ donation after controlled circulatory death (Maastricht classification III) following the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment in Korea: A suggested guideline. Korean J. Transplant. 2021, 35, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Zhou, H.; Cao, R.; Lin, M.; Hua, X.; Hong, L.; Huang, Z.; Na, N.; Cai, R.; Wang, G.; et al. Donation after brain death followed by circulatory death, a novel donation pattern, confers comparable renal allograft outcomes with donation after brain death. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheijde, J.L.; Rady, M.Y.; McGregor, J.L. The United States Revised Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (2006): New challenges to balancing patient rights and physician responsibilities. Philos. Ethics Humanit. Med. 2007, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radajewska, A.; Krzywonos-Zawadzka, A.; Bil-Lula, I. Recent Methods of Kidney Storage and Therapeutic Possibilities of Transplant Kidney. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Erp, A.C.; Rebolledo, R.A.; Hoeksma, D.; Jespersen, N.R.; Ottens, P.J.; Nørregaard, R.; Pedersen, M.; Laustsen, C.; Burgerhof, J.G.M.; Wolters, J.C.; et al. Organ-specific responses during brain death: Increased aerobic metabolism in the liver and anaerobic metabolism with decreased perfusion in the kidneys. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floerchinger, B.; Yuan, X.; Jurisch, A.; Timsit, M.O.; Ge, X.; Lee, Y.L.; Schmid, C.; Tullius, S.G. Inflammatory immune responses in a reproducible mouse brain death model. Transpl. Immunol. 2012, 27, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.; Rose, C.; Lesage, J.; Joffres, Y.; Gill, J.; O’Connor, K. Use and Outcomes of Kidneys from Donation after Circulatory Death Donors in the United States. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 3647–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijboer, W.N.; Moers, C.; Leuvenink, H.G.D.; Ploeg, R.J. How important is the duration of the brain death period for the outcome in kidney transplantation? Transpl. Int. 2011, 24, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, D.M.; Watson, C.J.E.; Pettigrew, G.J.; Johnson, R.J.; Collett, D.; Neuberger, J.M.; Bradley, J.A. Kidney donation after circulatory death (DCD): State of the art. Kidney Int. 2015, 88, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sereinigg, M.; Stiegler, P.; Puntschart, A.; Seifert-Held, T.; Zmugg, G.; Wiederstein-Grasser, I.; Marte, W.; Marko, T.; Bradatsch, A.; Tscheliessnigg, K.; et al. Establishing a brain-death donor model in pigs. Transplant. Proc. 2012, 44, 2185–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Cao, S.; Wang, T.; Yan, B.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Modified Brain Death Model for Rats. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2014, 12, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calne, R.Y.; Pegg, D.E.; Pryse-Davies, J.; Brown, F.L. Renal preservation by ice-cooling: An experimental study relating to kidney transplantation from cadavers. Br. Med. J. 1963, 2, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Li, H.K.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.W.; Ma, X. No safe renal warm ischemia time—The molecular network characteristics and pathological features of mild to severe ischemia reperfusion kidney injury. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1006917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knijff, L.W.D.; Van Kooten, C.; Ploeg, R.J. The Effect of Hypothermic Machine Perfusion to Ameliorate Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Donor Organs. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 848352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.M.; Bravo-Shugarman, M.; Terasaki, P.I. Kidney preservation for transportation. Lancet 1969, 294, 1219–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, G.; Okiye, S.E.; Zincke, H. Successful 24-Hour Preservation of the Ischemic Canine Kidney with Euro-Collins Solution. J. Urol. 1982, 128, 1401–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, J.; Xia, T.C.; Xu, R.; He, X.; Xia, Y. Preservation Solutions for Kidney Transplantation: History, Advances and Mechanisms. Cell Transplant. 2019, 28, 1472–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrowsky, H.; Clavien, P.A. Principles of Liver Preservation. In Transplantation of the Liver, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 582–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploeg, R.J.; Goossens, D.; Mcanulty, J.F.; Southard, J.H.; Belzer, F.O. Successful 72-hour cold storage of dog kidneys with uw solution. Transplantation 1988, 46, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, T.G. The perfusion of surviving organs. J. Physiol. 1903, 29, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzer, F.O.; Ashby, B.S.; Dunphy, J.E. 24-hour and 72-hour preservation of canine kidneys. Lancet 1967, 290, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southard, J.H.; Belzer, F.O. Organ Preservation. Annu. Rev. Med. 1995, 46, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belzer, F.O.; Ashby, B.S.; Gulyassy, P.F.; Powell, M. Successful Seventeen-Hour Preservation and Transplantation of Human-Cadaver Kidney. N. Engl. J. Med. 1968, 278, 608–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAnulty, J.F.; Ploeg, R.J.; Southard, J.H.; Belzer, F.O. Successful five-day perfusion preservation of the canine kidney. Transplantation 1989, 47, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maathuis, M.H.J.; Manekeller, S.; Van Der Plaats, A.; Leuvenink, H.G.; ’t Hart, N.A.; Lier, A.B.; Rakhorst, G.; Ploeg, R.J.; Minor, T. Improved Kidney Graft Function After Preservation Using a Novel Hypothermic Machine Perfusion Device. Ann. Surg. 2007, 246, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallinat, A.; Paul, A.; Efferz, P.; Lüer, B.; Kaiser, G.; Wohlschlaeger, J.; Treckmann, J.; Minor, T. Hypothermic Reconditioning of Porcine Kidney Grafts by Short-Term Preimplantation Machine Perfusion. Transplantation 2012, 93, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallinat, A.; Efferz, P.; Paul, A.; Minor, T. One or 4 h of “in-house” reconditioning by machine perfusion after cold storage improve reperfusion parameters in porcine kidneys. Transpl. Int. 2014, 27, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moers, C.; Smits, J.M.; Maathuis, M.H.; Treckmann, J.; van Gelder, F.; Napieralski, B.P.; van Kasterop-Kutz, M.; van der Heide, J.J.; Squifflet, J.P.; van Heurn, E.; et al. Machine Perfusion or Cold Storage in Deceased-Donor Kidney Transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochmans, I.; O’Callaghan, J.M.; Pirenne, J.; Ploeg, R.J. Hypothermic machine perfusion of kidneys retrieved from standard and high-risk donors. Transpl. Int. 2015, 28, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codas, R.; Thuillier, R.; Hauet, T.; Badet, L. Renoprotective effect of pulsatile perfusion machine RM3: Pathophysiological and kidney injury biomarker characterization in a preclinical model of autotransplanted pig. BJU Int. 2012, 109, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, J.M.; Morgan, R.D.; Knight, S.R.; Morris, P.J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of hypothermic machine perfusion versus static cold storage of kidney allografts on transplant outcomes. Br. J. Surg. 2013, 100, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tingle, S.J.; Figueiredo, R.S.; Moir, J.A.; Goodfellow, M.; Talbot, D.; Wilson, C.H. Machine perfusion preservation versus static cold storage for deceased donor kidney transplantation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD011671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindell, S.L.; Compagnon, P.; Mangino, M.J.; Southard, J.H. UW Solution for Hypothermic Machine Perfusion of Warm Ischemic Kidneys. Transplantation 2005, 79, 1358–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg, E.M.; Markmann, J.F. Machine Perfusion in Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation: Promises of Improved Outcomes but Gaps in Implementation. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2025, 85, 651–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, J.; Chilcott, J.; Holmes, M.; Brewer, N. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of pulsatile machine perfusion versus cold storage of kidneys for transplantation retrieved from heart-beating and non-heart-beating donors. Health Technol. Assess. 2003, 7, 1–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeckli, B.; Sun, P.; Lazeyras, F.; Morel, P.; Moll, S.; Pascual, M.; Bühler, L.H. Evaluation of donor kidneys prior to transplantation: An update of current and emerging methods. Transpl. Int. 2019, 32, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. LifePort Kidney Transporter for Preserving Kidneys. In Medical Technologies Guidance [MTG1]; NICE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, R.; Murray, E.; Thomson, P.C.; Mark, P.B.; Clancy, M.J.; Asher, J. The new UK national kidney allocation scheme with maximized “R4-D4” kidney transplants: Better patient-to-graft longevity matching may be at the cost of more resources. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2021, 19, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Von Horn, C.; Minor, T. Isolated kidney perfusion: The influence of pulsatile flow. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2018, 78, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosgood, S.A.; Callaghan, C.J.; Wilson, C.H.; Smith, L.; Mullings, J.; Mehew, J.; Oniscu, G.C.; Phillips, B.L.; Bates, L.; Nicholson, M.L. Normothermic machine perfusion versus static cold storage in donation after circulatory death kidney transplantation: A randomized controlled trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, E.; Sokolova, M.; Jager, N.M.; Schjalm, C.; Weiss, M.G.; Liavåg, O.M.; Maassen, H.; van Goor, H.; Thorgersen, E.B.; Pettersen, K.; et al. Normothermic Machine Perfusion Reconstitutes Porcine Kidney Tissue Metabolism but Induces an Inflammatory Response, Which Is Reduced by Complement C5 Inhibition. Transpl Int. 2024, 37, 13348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissenbacher, A.; Lo Faro, L.; Boubriak, O.; Soares, M.F.; Roberts, I.S.; Hunter, J.P.; Voyce, D.; Mikov, N.; Cook, A.; Ploeg, R.J.; et al. Twenty-four-hour normothermic perfusion of discarded human kidneys with urine recirculation. Am. J. Transplant. 2019, 19, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumbill, R.; Knight, S.; Hunter, J.; Fallon, J.; Voyce, D.; Barrett, J.; Ellen, M.; Conroy, E.; Roberts, I.S.; James, T.; et al. Prolonged normothermic perfusion of the kidney prior to transplantation: A historically controlled, phase 1 cohort study. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Wang, G.; He, H.; Yue, R.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, L.; Huang, W.; Guo, Y.; Yin, T.; Ma, L.; et al. Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carriers: Potential Applications in Solid Organ Preservation. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 760215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuillier, R.; Allain, G.; Celhay, O.; Hebrard, W.; Barrou, B.; Badet, L.; Leuvenink, H.; Hauet, T. Benefits of active oxygenation during hypothermic machine perfusion of kidneys in a preclinical model of deceased after cardiac death donors. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 184, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, F.A.; Czigany, Z.; Bednarsch, J.; Böcker, J.; Amygdalos, I.; Morales Santana, D.A.; Rietzler, K.; Moeller, M.; Tolba, R.; Boor, P.; et al. Hypothermic Oxygenated Machine Perfusion of Extended Criteria Kidney Allografts from Brain Dead Donors: Protocol for a Prospective Pilot Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2019, 8, e14622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husen, P.; Boffa, C.; Jochmans, I.; Krikke, C.; Davies, L.; Mazilescu, L.; Brat, A.; Knight, S.; Wettstein, D.; Cseprekal, O.; et al. Oxygenated End-Hypothermic Machine Perfusion in Expanded Criteria Donor Kidney Transplant: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizet, A. The isolated perfused kidney: Possibilities, limitations and results. Kidney Int. 1975, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brull, L.; Louis-Bar, D. Toxicity of Artificially Circulated Heparinised Blood on the Kidney. Arch. Int. Physiol. Biochim. 1957, 65, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, A. Some observations on the perfusion of the isolated kidney by a pump. J. Physiol. 1931, 71, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Horn, C.; Zlatev, H.; Lüer, B.; Malkus, L.; Ting, S.; Minor, T. The impact of oxygen supply and erythrocytes during normothermic kidney perfusion. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rother, T.; Horgby, C.; Schmalkuche, K.; Burgmann, J.M.; Nocke, F.; Jägers, J.; Schmitz, J.; Bräsen, J.H.; Cantore, M.; Zal, F.; et al. Oxygen carriers affect kidney immunogenicity during ex-vivo machine perfusion. Front. Transplant. 2023, 2, 1183908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alayash, A.I.; D’Agnillo, F.; Buehler, P.W. First-generation blood substitutes: What have we learned? Biochemical and physiological perspectives. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2007, 7, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callas, D.D.; Clark, T.L.; Moreira, P.L.; Lansden, C.; Gawryl, M.S.; Kahn, S.; Bermes, E.W., Jr. In vitro effects of a novel hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier on routine chemistry, therapeutic drug, coagulation, hematology, and blood bank assays. Clin. Chem. 1997, 43, 1744–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, R.N.; Patel, S.V.B.; Sun, Q.; Jiang, L.; Richard-Mohamed, M.; Ruthirakanthan, A.; Aquil, S.; Al-Ogaili, R.; Juriasingani, S.; Sener, A.; et al. Renal Protection Against Ischemia Reperfusion Injury: Hemoglobin-based Oxygen Carrier-201 Versus Blood as an Oxygen Carrier in Ex Vivo Subnormothermic Machine Perfusion. Transplantation 2020, 104, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverne, Y.J.; de Wijs-Meijler, D.; te Lintel Hekkert, M.; Moon-Massat, P.F.; Dubé, G.P.; Duncker, D.J.; Merkus, D. Normalization of hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier-201 induced vasoconstriction: Targeting nitric oxide and endothelin. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 123, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuillier, R.; Dutheil, D.; Trieu, M.T.; Mallet, V.; Allain, G.; Rousselot, M.; Denizot, M.; Goujon, J.M.; Zal, F.; Hauet, T. Supplementation with a New Therapeutic Oxygen Carrier Reduces Chronic Fibrosis and Organ Dysfunction in Kidney Static Preservation. Am. J. Transplant. 2011, 11, 1845–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, J.; Hannaert, P.; Kasil, A.; Thuillier, R.; Leize, E.; Delpy, E.; Steichen, C.; Goujon, J.M.; Zal, F.; Hauet, T. Efficacy of the natural oxygen transporter HEMO 2 life ® in cold preservation in a preclinical porcine model of donation after cardiac death. Transpl. Int. 2019, 32, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasil, A.; Giraud, S.; Couturier, P.; Amiri, A.; Danion, J.; Donatini, G.; Matillon, X.; Hauet, T.; Badet, L. Individual and Combined Impact of Oxygen and Oxygen Transporter Supplementation during Kidney Machine Preservation in a Porcine Preclinical Kidney Transplantation Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix, P.; Val-Laillet, D.; Turlin, B.; Ben Mosbah, I.; Burel, A.; Bobillier, E.; Bendavid, C.; Delpy, E.; Zal, F.; Corlu, A.; et al. Adding the oxygen carrier M101 to a cold-storage solution could be an alternative to HOPE for liver graft preservation. JHEP Rep. 2020, 2, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak-Barańska, J.; Boguszewska, K.; Adamus-Grabicka, A.; Karwowski, B.T. Two Faces of Vitamin C—Antioxidative and Pro-Oxidative Agent. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Suh, J.; Carr, A.C.; Morrow, J.D.; Zeind, J.; Frei, B. Vitamin C suppresses oxidative lipid damage in vivo, even in the presence of iron overload. Am. J. Physiol-Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 279, E1406–E1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopacka, M.; Palyvoda, O.; Rzeszowska-Wolny, J. Inhibitory effect of ascorbic acid post-treatment on radiation-induced chromosomal damage in human lymphocytes in vitro. Teratog. Carcinog. Mutagen. 2002, 22, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostróżka-Cieślik, A.; Dolińska, B.; Ryszka, F. The Effect of Modified Biolasol Solution on the Efficacy of Storing Isolated Porcine Kidneys. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7465435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleilevens, C.; Doorschodt, B.M.; Fechter, T.; Grzanna, T.; Theißen, A.; Liehn, E.A.; Breuer, T.; Tolba, R.H.; Rossaint, R.; Stoppe, C.; et al. Influence of Vitamin C on Antioxidant Capacity of In Vitro Perfused Porcine Kidneys. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gochi, M.; Kato, F.; Toriumi, A.; Kawagoe, T.; Yotsuya, S.; Ishii, D.; Otani, M.; Nishikawa, Y.; Furukawa, H.; Matsuno, N. A Novel Preservation Solution Containing Quercetin and Sucrose for Porcine Kidney Transplantation. Transplant. Direct 2020, 6, e624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhu, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Ning, J.; Xiao, C. Hydrogen sulfide treatment protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury via induction of heat shock proteins in rats. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2018, 22, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, M.A.J.; Arcand, S.; Lin, H.B.; Wojnarowicz, C.; Sawicka, J.; Banerjee, T.; Luo, Y.; Beck, G.R.; Luke, P.P.; Sawicki, G. Protection of the Transplant Kidney from Preservation Injury by Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteinases. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosi, N.; Guerrieri, D.; Caro, F.; Sanchez, F.; Haeublein, G.; Casadei, D.; Incardona, C.; Chuluyan, E. Alpha Lipoic Acid: A Therapeutic Strategy that Tend to Limit the Action of Free Radicals in Transplantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Kampfrath, T.; Sun, Q.; Parthasarathy, S.; Rajagopalan, S. Evidence that α-lipoic acid inhibits NF-κB activation independent of its antioxidant function. Inflamm. Res. 2011, 60, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.H.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, J.; Ma, S.K.; Kim, N.H.; Choi, K.C.; Frøkiaer, J.; Nielsen, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, S.Z.; et al. Effects of α-lipoic acid on ischemia-reperfusion-induced renal dysfunction in rats. Am. J. Physiol-Ren. Physiol. 2008, 294, F272–F280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Dugbartey, G.J.; Juriasingani, S.; Sener, A. Hydrogen Sulfide Metabolite, Sodium Thiosulfate: Clinical Applications and Underlying Molecular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Chan, A.; Ali, S.; Saha, A.; Haushalter, K.J.; Lam, W.L.; Glasheen, M.; Parker, J.; Brenner, M.; Mahon, S.B.; et al. Hydrogen Sulfide—Mechanisms of Toxicity and Development of an Antidote. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackstone, E.; Morrison, M.; Roth, M.B. H2S Induces a Suspended Animation-Like State in Mice. Science 2005, 308, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackstone, E.; Roth, M.B. Suspended animation-like state protects mice from lethal hypoxia. Shock 2007, 27, 370–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, P.M.; De Boer, R.A.; Bos, E.M.; van den Born, J.C.; Ruifrok, W.P.; Vreeswijk-Baudoin, I.; van Dijk, M.C.; Hillebrands, J.L.; Leuvenink, H.G.; van Goor, H. Gaseous Hydrogen Sulfide Protects against Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Mice Partially Independent from Hypometabolism. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strutyns’ka, N.A.; Semenykhina, O.M.; Chorna, S.V.; Vavilova, H.L.; Sahach, V.F. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits Ca2+-induced mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening in adult and old rat heart. Fiziolohichnyi Zhurnal 2011, 57, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Goto, Y.I.; Kimura, H. Hydrogen Sulfide Increases Glutathione Production and Suppresses Oxidative Stress in Mitochondria. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Taka, M.; Dugbartey, G.J.; Richard-Mohamed, M.; McLeod, P.; Jiang, J.; Major, S.; Arp, J.; O’Neil, C.; Liu, W.; Gabril, M.; et al. Evaluating the Effects of Kidney Preservation at 10 °C with Hemopure and Sodium Thiosulfate in a Rat Model of Syngeneic Orthotopic Kidney Transplantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Dugbartey, G.J.; Juriasingani, S.; Akbari, M.; Liu, W.; Haig, A.; McLeod, P.; Arp, J.; Sener, A. Sodium thiosulfate-supplemented UW solution protects renal grafts against prolonged cold ischemia-reperfusion injury in a murine model of syngeneic kidney transplantation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 145, 112435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juriasingani, S.; Jackson, A.; Zhang, M.Y.; Ruthirakanthan, A.; Dugbartey, G.J.; Sogutdelen, E.; Levine, M.; Mandurah, M.; Whiteman, M.; Luke, P.; et al. Evaluating the Effects of Subnormothermic Perfusion with AP39 in a Novel Blood-Free Model of Ex Vivo Kidney Preservation and Reperfusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugbartey, G.J.; Juriasingani, S.; Richard-Mohamed, M.; Rasmussen, A.; Levine, M.; Liu, W.; Haig, A.; Whiteman, M.; Arp, J.; Luke, P.P.W.; et al. Static Cold Storage with Mitochondria Targeted Hydrogen Sulfide Donor Improves Renal Graft Function in an Ex Vivo Porcine Model of Controlled Donation-after-Cardiac-Death Kidney Transplantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, P.; Dugbartey, G.J.; McFarlane, L.; McLeod, P.; Major, S.; Jiang, J.; O’Neil, C.; Haig, A.; Sener, A. Effect of Sodium Thiosulfate Pre-Treatment on Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Kidney Transplantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.P.; Zhu, J.G.; Wu, J.P.; Xie, J.J.; Xu, L.W. Experimental Study on Early Protective Effect of Ischemic Preconditioning on Rat Kidney Graft. Transplant. Proc. 2009, 41, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wever, K.E.; Warle, M.C.; Wagener, F.A.; van der Hoorn, J.W.; Masereeuw, R.; van der Vliet, J.A.; Rongen, G.A. Remote ischaemic preconditioning by brief hind limb ischaemia protects against renal ischaemia-reperfusion injury: The role of adenosine. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 3108–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soendergaard, P.; Krogstrup, N.V.; Secher, N.G.; Ravlo, K.; Keller, A.K.; Toennesen, E.; Bibby, B.M.; Moldrup, U.; Ostraat, E.O.; Pedersen, M.; et al. Improved GFR and renal plasma perfusion following remote ischaemic conditioning in a porcine kidney transplantation model. Transpl. Int. 2012, 25, 1002–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, R.S.; Schnuelle, P.; Nickels, L.; Jarczyk, J.; Waldherr, R.; Theisinger, S.; Theisinger, B.; Klotz, S.; Tsagogiorgas, C.; Göttmann, U.; et al. N-Octanoyl Dopamine for Donor Treatment in a Brain-death Model of Kidney and Heart Transplantation. Transplantation 2015, 99, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, R.; Xue, S.; Zhu, H.; Sun, X.; Sun, X. Protective effects of three remote ischemic conditioning procedures against renal ischemic/reperfusion injury in rat kidneys: A comparative study. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 184, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.; Park, H.Y.; Lim, C.H.; Kim, H.J.; Jang, Y.; Seong, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Shin, H.J. The effect of remote ischemic conditioning on mortality after kidney transplantation: The systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Definition | Type of DCD |

|---|---|---|

| I | Dead when arrived at hospital (1) Cardiocirculatory death outside hospital with no witnesses. (2) Cardiocirculatory death outside hospital with witnesses or rapid resuscitation attempt. | Uncontrolled |

| II | Unsuccessful cardiopulmonary resuscitation: witnessed cardiac arrest outside the hospital with unsuccessful cardiopulmonary resuscitation | Uncontrolled |

| III | Cardiac arrest following the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments but not considered to be brain dead | Controlled |

| IV | Cardiac arrest in the process of the determination of death by neurological criteria after brain death or after such determination has been performed, but before being transferred to an operating room | Uncontrolled |

| V | Cardiac arrest in hospital patients | Uncontrolled |

| Rate of Outcomes | Type of Deceased Donor Graft | |

|---|---|---|

| DCD | DBD | |

| Discard Rates | 34% [41] | 24% [41] |

| DGF | 30–50% [31] | 20% [42] |

| 5-Year Survival | 76% [31] | 75% [36] |

| Solution | Key Composition/Innovations | Experimental Model | Preservation Duration (0–4 °C) | Main Findings/Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hank’s Solution (1963) | Mimicked extracellular fluid | Canine kidneys | Up to 12 h | Kidneys functioned immediately post-transplant with normal creatinine. Failed at 24 h due to cold ischemia injury [46]. |

| Saline | Simple isotonic saline | Canine kidneys | Up to 16 h | Kidneys resisted ischemia up to 16 h at 0–4 °C [49]. |

| Solution C | Simulated intracellular fluid (↑ K+, ↓ Na+) to reduce ischemia-induced edema | Canine kidneys | Up to 30 h | Lower serum creatinine after prolonged ischemia. Ineffective if >20 min warm ischemia before storage [49,50]. |

| Euro-Collins Solution | Modified Collins: ↑ Glucose (195 vs. 140 mmol), removed Mg2+ | DCD canine model (35 min warm ischemia) | Up to 24 h | Effectively preserved renal grafts; improved post-transplant outcomes. Adopted clinically in Europe (1980s) [51]. |

| University of Wisconsin (UW) Solution | Intracellular-type solution with impermeants (lactobionate, raffinose), antioxidants (glutathione), colloid (HES) | Canine kidneys | Up to 72 h | Significantly higher graft viability and function after transplantation compared to EC solution [52,54]. |

| Storage Method/Reagent | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Static Cold Storage (SCS) |

| Increased risk of DGF, especially in DCD kidneys |

| Hypothermic Machine Perfusion (HMP) | Improved outcomes of DGF (particularly for DCD kidneys) |

|

| Normothermic Machine Perfusion (NMP) | Allows for closer monitoring of graft function. |

|

| Oxygenated HMP (oxHMP) | Provides some oxygen during hypoxia to prevent some ischemic damage [79] |

|

| Whole Blood Perfusion | More efficient in oxygenation than oxHMP [82] |

|

| Perfusion with Isolated Red Blood Cells (RBCs) |

|

|

| Acellular Oxygen Carriers (M101, Hemopure) |

|

|

| Compound | Mechanism of Action | Experimental Model | Main Findings/Outcomes | Notes/Limitations |

| Vitamin C | Water-soluble antioxidant; donates protons/electrons via lactone ring; inhibits lipid peroxidation (↓ MDA, 4-HNE); enhances DNA repair | Porcine kidney perfusion with Biolasol ± Vit C [88]; in vitro porcine kidneys perfused in Ringer’s ± Vit C [99] | Preserved cytoskeletal integrity vs. control; ↓ oxidative stress in vitro | Did not significantly reduce release of injury markers or overall tissue damage |

| Quercetin | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic; improves graft quality/function | UW solution + quercetin [100] | Improved graft function with supplementation | Also inhibits heat shock proteins (HSPs), which may counteract protection since ↑HSPs are beneficial in IRI [101] |

| Doxycycline (DOXY) | MMP inhibitor; prevents ECM degradation and inflammation | Rat model of cold ischemic perfusion [102] | ↓ Damage markers released into perfusate; improved graft protection | Limited to preclinical data |

| Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) | Endogenous mitochondrial antioxidant; directly scavenges ROS; inhibits NF-κB translocation (anti-inflammatory) | Rat renal IRI model (40 min warm ischemia; ALA given 24/48 h before and 6/24 h after ischemia) [105] | ↑ Creatinine clearance; ↓ plasma creatinine at 2 days post-IRI | Already FDA-approved for diabetic neuropathy [104] |

| Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) & Donors (NaHS, Na2S, GYY4137, AP39, STS, garlic polysulfides) | Modulates mitochondrial respiration (↓ O2 consumption, reversible inhibition of complex IV); induces hypometabolic state; antioxidant via ↑ GSH; inhibits mPTP opening; vasodilatory | Rodent and porcine renal transplant models [113,114,115,116,117]; myocardial IRI mouse models [110] | Safely extended cold ischemic time; ↓ tissue injury; improved graft quality and post-transplant outcomes | Toxic at high concentrations (500–1000 ppm); dose-dependent; STS is clinically viable donor |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ortas, T.S.; Choudhary, O.; Dugbartey, G.J.; Sener, A. Preclinical Models of Donation-After-Circulatory-Death and Brain-Death: Advances in Kidney Preservation and Transplantation. Biology 2025, 14, 1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101415

Ortas TS, Choudhary O, Dugbartey GJ, Sener A. Preclinical Models of Donation-After-Circulatory-Death and Brain-Death: Advances in Kidney Preservation and Transplantation. Biology. 2025; 14(10):1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101415

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtas, Tamara S., Omer Choudhary, George J. Dugbartey, and Alp Sener. 2025. "Preclinical Models of Donation-After-Circulatory-Death and Brain-Death: Advances in Kidney Preservation and Transplantation" Biology 14, no. 10: 1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101415

APA StyleOrtas, T. S., Choudhary, O., Dugbartey, G. J., & Sener, A. (2025). Preclinical Models of Donation-After-Circulatory-Death and Brain-Death: Advances in Kidney Preservation and Transplantation. Biology, 14(10), 1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14101415