Simple Summary

Edible insects can provide an alternative and sustainable source of dietary protein to meet the future demand of the growing global population. Therefore, this study analysed the impact of mealworm (Alphitobius diaperinus L.) larvae hydrolysis using artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) flower’s enzyme extract, on the production of peptide hydrolysates with potential bioactivity. The antioxidant capacity against the 1,1,-diphenil-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical and the angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitory activity of the hydrolysates were determined. Furthermore, the identification of the peptide sequences was conducted to detect the potential bioactive peptides in the hydrolysates. The results reveal that the water-soluble extract of artichoke flower could be suitable for producing bioactive peptides from mealworm larvae, and could be incorporated as an ingredient in future functional food products.

Abstract

In this study, we aimed to obtain hydrolysates with bioactive peptides from mealworm (Alphitobius diaperinus L.) larvae using an artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) enzyme extract. Two types of substrates were used: the raw larvae flour (LF) and its protein extract (PE). The hydrolysis yield, considering the peptide concentration of the hydrolysates, was higher in PE hydrolysates than in LF hydrolysates (6.39 ± 0.59 vs. 3.02 ± 0.06 mg/mL, respectively). However, LF showed a higher antioxidant activity against the DPPH radical than PE (59.10 ± 1.42 vs. 18.79 ± 0.81 µM Trolox Eq/mg peptides, respectively). Regarding the inhibitory activity of angiotensin-I-converting enzyme (ACE), an IC50 value of 111.33 ± 21.3 µg peptides/mL was observed in the PE. The identification of the peptide sequence of both hydrolysates was conducted, and LF and its PE presented 404 and 116 peptides, respectively, most with low molecular weight (<3 kDa), high percentage of hydrophobic amino acids, and typical characteristics of well-known antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory peptides. Furthermore, the potential bioactivity of the sequences identified was searched in the BIOPEP database. Considering the antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory activities, LF hydrolysates contained a larger number of sequences with potential bioactivity than PE hydrolysates.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of diseases such as hypertension or cardiovascular problems is related to nutritional factors. This relationship between health and nutrition has given rise to a growing interest in society for functional foods, which, besides their nutritional characteristics, offer healthy properties [1]. One component of these functional foods is bioactive peptides, because they provide a beneficial physiological effect due to their multifunctional biological activities such as antioxidative, antihypertensive, antimicrobial, anticancer, antidiabetic, and immunomodulatory, among others [2]. These peptides are short chains of amino acids that are inactive within the original protein and can be released during gastrointestinal digestion or during the industrial processing of certain foods [3]. Obtaining peptides from proteins can be conducted using different methods such as microbial fermentation, used mainly for dairy products, and enzymatic hydrolysis, being the fastest and easiest technique to control [4]. Bioactive peptides are being widely studied to determine their effects on the key systems of the human body, such as the digestive, cardiovascular, nervous, and immune systems. Among the bioactive peptides, those with antihypertensive activity are probably the most studied [5]. In recent years, peptides with antihypertensive activity have been identified in dairy [6,7], egg [8], marine [9], and vegetable [10] products. Insects can also be a good source of bioactive peptides, because they have a high protein content (over 70% of dry weight), which allows the supply of essential amino acids with high nutritional and unsaturated fat levels [11], compared to the contribution from other animals for consumption [12,13]. Therefore, there is considerable interest in promoting and improving the consumption of insects, which have a growing presence in the agri-food chain, as transformed animal protein derived from insects can be used to produce feed for farm animals and aquaculture [14]. Recently, the European Union has authorized the commercialization of three insect species for human consumption: Tenebrio molitor, Locusta migratoria, and Acheta domesticus, that comply with the Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 on novel foods [15]. In the future, using edible insects as a functional ingredient to develop enriched foods could be considered because of the presence of bioactive peptides. However, the research of bioactive peptide extraction in insects is limited, with some reported studies on crickets, locusts, grasshoppers, and silkworms [16]. The silkworm is one of the most studied insects for obtaining bioactive peptides with antimicrobial, antihypertensive, antioxidant, antidiabetic, anticancer, and hepatoprotective properties [17,18]. Studies about antihypertensive activity in insect protein hydrolysates were published for various species (Bombix mori, Bombus terrestris, Schistocerca gregaria, and Spodoptera littoralis), using enzymes of different origin (gastrointestinal proteases, thermolysin, and alcalase), and observing inhibitory activity of the angiotensin-I-converting enzyme (ACE) [19]. Furthermore, the antioxidant activity of insect hydrolysates (S. littoralis, G. sigillatus, A. diaperinus, B. mori, B. dubia, etc.) has also been determined when using different enzymes, mostly gastrointestinal proteases, but also thermolysin, alcalase, and papain [20,21,22,23]. The most common way of obtaining bioactive peptides is through enzymatic hydrolysis, mainly using enzymes of animal origin; thus, it is convenient to study other proteases of plant origin such as cynarases—aspartic proteases present in flowers of the genus Cynara [24]. Enzyme extracts are obtained from the mature artichoke flower, C. scolymus L. These enzymes present a wide proteolytic activity and produce elevated concentrations of hydrophobic peptides demonstrated to possess higher bioactivity than hydrophilic ones [5,25]. Moreover, the mature artichoke flower constitutes an agricultural residue at the end of the season, and its use to obtain enzymes extracts could give rise to the revaluation of this waste culture. Thus, the aim of this study was to prepare hydrolysates from larvae of A. diaperinus L. with enzymatic extracts of the artichoke flower and to evaluate their antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory activities. Furthermore, the peptide sequence identification of the hydrolysates was conducted and the deliverables were analyzed using the BIOPEP database [26].

2. Materials and Methods

Mature artichoke flowers (C. scolymus L.) were collected from the Region of Murcia (Spain). Vacuum-packed A. diaperinus L. larvae were provided by Proti-Farma (Holland). ACE from rabbit lung, the ACE synthetic substrate, hippuryl-L-histidyl-L-leucine (HHL), and 1,1-diphenil-2-picrylhydrazyl) (DPPH) were purchased from Sigma Chemicals Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.1. Preparation of C. scolymus L. Extract

The stigmas and stiles of the mature artichoke flower were macerated for 24 h in distilled water at room temperature. The water-soluble extract was filtrated and then centrifuged for 5 min at 4000× g. The supernatant obtained was filtrated, lyophilized and kept at −20 °C until use [27]. The enzymatic extract protein concentration [28] was 0.104 ± 0.01 (w/w).

2.2. A. diaperinus L. larvae Flour and Protein Extract Preparation

To obtain the larvae flour (LF), 100 g of dried A. diaperinus L. larvae with a 58.6% protein content were minced using a grinder until a homogeneous powder was achieved. Next, the protein extract (PE) was obtained [29]: 50 g of larval meal was diluted with 500 mL of distilled water and the pH was adjusted to 8.0 with NaOH (0.1 M). After constant stirring for 30 min, the homogenate was centrifuged at 3220× g for 15 min. The pH of the supernatant was adjusted to 4.5 with HCl (0.1 N) to precipitate the protein. The resulting solution was centrifuged again at 3220× g for 15 min and the precipitate obtained was subjected to washing phases with distilled water at pH 4.5. The protein content of the PE, determined by the Kjeldahl method [30], was 31.65% ± 0.81. The preparation of the samples (LF and PE) was performed in triplicate.

2.3. Obtaining Hydrolysates

Hydrolysates of LF and its PE with the artichoke enzymatic extract were prepared following the method described by Timón et al. (2014) [31], with some modifications. Briefly, substrates (LF and PE) were dissolved in citrate buffer (pH 6.2), adjusting the protein content concentration to 1% (w/v). The solutions were mixed with the enzymatic extract at a final concentration of 22.1 µg of artichoke extract protein/mL of LF or PE solution, respectively, and incubated for 16 h in a shaking bath at 50 °C, according to optimal hydrolysis conditions established previously [5]. The hydrolysis was halted by raising the temperature to 100 °C for 10 min and the remaining non-hydrolyzed protein was precipitated by adjusting the pH to 4.5 with HCl (0.1 N). The samples were centrifuged at 3220× g for 30 min and the supernatant was collected and filtered through 0.45 µm Nylon discs. Last, the pH was adjusted to 7.0 with NaOH (0.1 M) and distributed in Falcon tubes for storage at −20 °C until use. Each type of hydrolysate was obtained in triplicate.

2.4. Peptide Concentration of Hydrolysates

The quantity of peptides was determined after precipitating the residual protein with 5% trichloroacetic acid (1:2, v/v) and centrifuging at 3220× g for 20 min. The nitrogen content in the supernatant was determined by the Kjeldahl method [30], and the peptide concentration was calculated using a conversion factor of 6.25. The peptide content determination for each type of hydrolysate was conducted in triplicate.

2.5. Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant activity against 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical was determined [32]. First, the hydrolysate was mixed with ethanol (1:1, v/v). Then, 125 µL of 0.02% DPPH in ethanol (w/v) were added to 1 mL of the hydrolysate solution. The reaction was maintained for 1 h at room temperature, protected from light, and after that, was centrifuged for 2 min at 10,000× g. The supernatant absorbance at 517 nm was measured. The radical scavenging activity (RSA) was calculated using Equation (1):

Acontrol being the measurement of the radical with distilled water, Asample the measurement of the DPPH in presence of the sample, and Ablank the measurement of a solution of ethanol in distilled water (1:1, v/v). The Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) of the hydrolysates (µM Trolox Eq/mg peptide) was determined using the following linear equation: y = 3.4789x + 0.0289 (R2 = 0.997). The analyses for the different hydrolysates were performed three times.

DPPH RSA % = [((Acontrol − Ablank) − (Asample − Ablank))/(Acontrol − Ablank)] × 100

2.6. Angiotensin-I-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity

The ACE inhibitory activity of the hydrolysates was conducted [33]. The hydrolysates (40 µL) were incubated at 37 °C with 100 µL 5 mM HHL dissolved in 0.1 M borate buffer and 0.3 M NaCl (pH 8.3). Then, 2 mU of ACE were incorporated into the substrate. The reaction was interrupted after 30 min, adding 150 µL of 1 M HCl. The hippuric acid formed was recovered through 1000 µL of ethyl acetate and centrifuged for 10 min at 4000× g; the organic phase (800 µL) was collected. Ethyl acetate was eliminated by increasing the temperature to 95 °C. The resulting hippuric acid was resuspended in 1000 µL of distilled water, and the absorbance at 228 nm was measured. The ACE inhibitory activity was determined applying Equation (2):

Acontrol being the measurement of hippuric acid produced by the action of non-inhibited ACE, Asample the measurement of the hippuric acid produced by the action of ACE with the sample, and Ablank the measurement of non-reacting HHL. The IC50 value was obtained in triplicate.

ACE inhibitory activity (%) = ((Acontrol − Ablank) − (Asample − Ablank))/(Acontrol − Ablank)) × 100

2.7. Peptide Sequence Identification

The identification of the sequences of the peptides of each type of hydrolysate was accomplished through nano-liquid chromatography–tandem MS analysis, previously carrying out a trypsin digestion [34]. The MS2 spectra were searched with the SEQUEST HT engine against a UniProtKB database (2019 UniProt consortium; https://www.uniprot.org, accessed on 4 May 2020). The peptides and their respective quantification were identified (with high confidence and without post-translational modifications) from each sample through the peptide spectral matches (PSM). The quantification values were normalized, paying attention to all PSM in the sample. Thus, the quantification of a single peptide was comparable between different samples. A search for each peptide identified in the BIOPEP bioactive peptide database was conducted [26]. Two different analyses were conducted: identification of biopeptides in a bioactive state in the hydrolysate; and identification of peptides with potential bioactivity, because they contain bioactive sequence fragments in their primary structure. Data analysis was performed with R (version 3.4.0; https://www.r-project.org, accessed on 1 June 2020).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 21.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), and a one-way ANOVA test was also performed. The means values were considered statistically different when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Hydrolysis Substrate on the Peptide Concentration

The type of substrate used in the hydrolysis (LF or PE) influenced the enzymatic production of peptides. Here, enzymatic hydrolysis of PE with artichoke flower extract after 16 h yielded a higher concentration of peptides (6.39 ± 0.59 mg/mL) than the hydrolysates from LF (3.02 ± 0.06 mg/mL) (p = 0.001). This may be due to the plant proteases acting more efficiently on the PE proteins than on the whole LF, because there would be no interactions with other compounds.

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

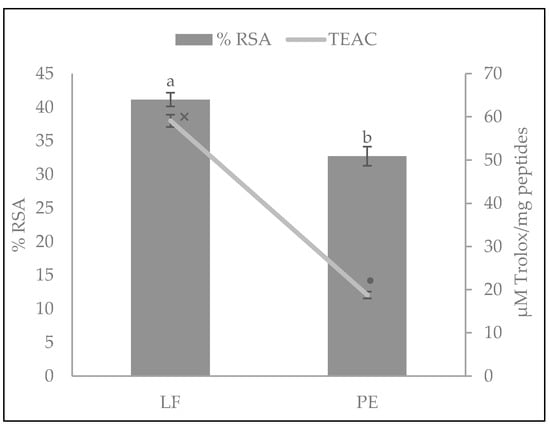

The DPPH radical antioxidant activities of the LF and PE hydrolysates are presented in Figure 1. The type of substrate had a significantly statistical influence (p < 0.01) on the DPPH RSA of the samples. Although both hydrolysates exerted antioxidant activity, the LF hydrolysate presented a higher RSA (41.15 ± 0.99%) than PE (32.72 ± 1.41%). This difference may be due to the total LF possibly containing other compounds besides peptides, that could contribute to the antioxidant capacity, and because of the greater number of different peptides identified in this type of hydrolysate and higher quantity of potential antioxidant sequences, as described in Section 3.4.

Figure 1.

Antioxidant activity of A. diaperinus larvae flour (LF) and its protein extract (PE) hydrolysates against 1,1-Diphenyl-1-pycrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical. Bars show the radical scavenging activity percentage (RSA%) and the line represents the Trolox equivalent activity capacity (TEAC: µM of Trolox equivalents per mg of peptides). Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Bars with different letters (a, b) and TEAC values (line) with distinct symbols (×, •) were statistically different (p < 0.008 and p < 0.001, respectively).

3.3. ACE-Inhibitory Activity

The IC50 value of the ACE-inhibitory activity of the PE hydrolysates was 111.33 ± 21.3 µg peptides/mL. However, it was not possible to determine the ACE inhibition IC50 value of raw LF hydrolysates, because no repetitive results were obtained. This may be due to the lack of purification of this type of sample, which could cause assay interferences.

3.4. Peptide Sequence Identification

In LF and its PE hydrolysates, 404 and 116 peptides were identified, respectively (data not shown), of which the majority (375 and 113, respectively) had a molecular weight lower than 3 kDa. We also observed many peptides with hydrophobic residues in both hydrolysates. Thus, Table 1 and Table 2 list the LF and PE hydrolysate peptides with molecular weight <1.5 kDa that contain at least 50% of hydrophobic amino acids, respectively.

Table 1.

Amino acid sequences of peptides from raw larvae flour hydrolysate determined by nLC-MS/MS with a molecular weight <1.5 kDa and minimum 50% of hydrophobic amino acids.

Table 2.

Amino acid sequences of peptides from larvae protein extract hydrolysate determined by nLC-MS/MS with a molecular weight <1.5 kDa and minimum 50% hydrophobic amino acids.

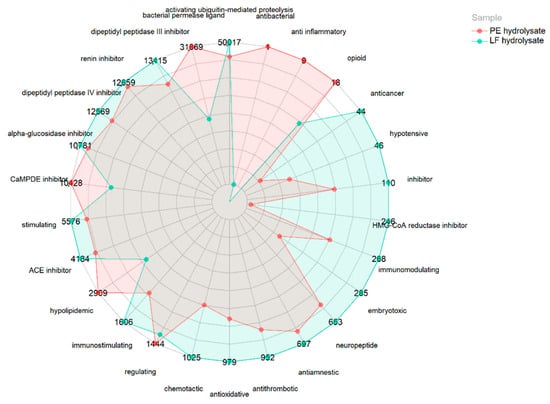

No peptides were found in the bioactive peptide database (BIOPEP [21]). However, many contain fragments of sequences with reported bioactivity in their primary structure. Therefore, Figure 2 shows the distribution of a normalized quantification (based on all PSM of the peptides in the samples) of the potential bioactivities of both hydrolysates as they contain bioactive sequence fragments collected in the BIOPEP database [26]. The LF hydrolysate possessed a higher potential bioactivity because it contained a larger number of sequence fragments with previously reported bioactivity, highlighting the activities of activating ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, bacterial permease ligand activity, dipeptidyl peptidase III inhibition, renin inhibition, dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibition, α-glucosidase inhibition, calmodulin-dependent cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase inhibition (CaMPDE inhibition), stimulating activity, hypolipidemic activity, and immunostimulating activity. Moreover, the PE hydrolysate presented a greater number of potential bioactive peptide sequences with bacterial permease ligand activity, CaMPDE inhibition activity, and hypolipidemic activity. Regarding ACE inhibition, raw LF hydrolysates showed a larger number of possible sequence fragments with putative activity than PE hydrolysates (4,183,560 and 3,703,948, respectively). Likewise, considering antioxidant capacity, LF hydrolysate presented many possible sequences with bioactivity than PE hydrolysates (979,440 and 682,783, respectively).

Figure 2.

Normalized quantification of potential bioactive sequences (×10−3) of raw larva meal (LF) and its protein extract (PE) hydrolysates. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry peptide spectral matches (PSM) have been conducted considering the existence of reported bioactive sequences within their primary structure. The values were normalized considering the PSM of the total peptides in the hydrolysates. Thus, the quantification of a sequence between the hydrolysates was comparable.

4. Discussion

4.1. DPPH Antioxidant Activity

Studies have been conducted in which the antioxidant activity of hydrolysates from insects was also determined using in vitro techniques, with highly variable results. Vercruysse et al. determined the antioxidant activity of different cotton leafworm (Spodoptera littoralis L.) hydrolysates using alcalase and thermolysin enzymes, obtaining a DPPH RSA percentage lower than 20% in both cases [3]. However, Yang et al. reported a high level of DPPH RSA (67.5%) from Bombyx mori L. hydrolysates obtained with alcalase [22]. Furthermore, Tenebrio molitor hydrolysates, obtained using a combination of alcalase and flavourzyme enzymes, showed 83 µM Trolox equivalents/mg [35], which is a higher activity than that observed in A. diaperinus hydrolysates from artichoke extract (53.10 µM Trolox equivalents/mg). Likewise, Hall et al. reported a DPPH antioxidant capacity between 872.4 and 1490.5 µmol Trolox/mg in cricket (Grillodes sigilatus) protein hydrolysates using an alcalase enzyme [20].

However, artichoke enzyme extracts have been used to obtain hydrolysates with antioxidant activity from different food matrices. The antioxidant and ACE-I inhibitory activities of the hydrolysates of bovine casein, ovalbumin, and A. diaperinus from water-soluble enzymatic artichoke extract, over 16 h of hydrolysis, are summarized in Table 3. Thus, bovine casein and ovalbumin hydrolysates showed a DPPH antioxidant activity of 4.35 and 13.03 µM Trolox Eq/mg peptides, respectively [8,34], which is a lower activity than that observed in A. diaperinus LF and its PE hydrolysates (18.79 and 59.10 µM Trolox Eq/mg, respectively). These results reveal the importance of the enzyme-substrate specificity when obtaining peptides with antioxidant activity. Therefore, A. diaperinus protein could be considered a better hydrolysis substrate from cinarases (compared to bovine casein and ovalbumin) to obtain antioxidant peptides against the DPPH radical.

Table 3.

Antioxidant activity against DPPH radical and ACE-I inhibitory activity of different protein substrate hydrolysates (bovine casein and ovalbumin) obtained with water-soluble enzymatic artichoke extract in comparison with the A. diaperinus total larvae flour (LF) and its protein extract (PE) hydrolysates.

4.2. ACE-Inhibitory Activity

Many studies on insect bioactive peptides have evaluated their ACE inhibition capacity. Vercruysse et al. prepared different insect species protein hydrolysates (Bombus terrestris, Schistocerca gregaria, Spodoptera littoralis, and Bombyx mori) with alcalase enzyme, showing IC50 values of: 2.97, 19.67, 3.86, and 6.49 mg/mL, respectively. In addition, S. littoralis and B. mori thermolysin hydrolysates presented IC50 values of 4.54 and 1.52 mg/mL, respectively [19]. Furthermore, S. littoralis after digestion with gastrointestinal enzymes and mucosal peptidases showed an IC50 value of 0.211 mg/mL [3]. Likewise, Wu et al. obtained B. mori hydrolysates through simulated gastrointestinal digestion with an IC50 value of 1.508 mg/mL, and its 5 kDa fraction showed an IC50 of 0.596 mg/mL [36]. The IC50 values were much higher, indicating lower ACE inhibition, than observed with A. diaperinus PE hydrolysates here (0.111 mg/mL).

Sousa et al. prepared A. diaperinus hydrolysates using 2.5 L alcalase and Corolase PP. The A. diaperinus hydrolysate with Colorase gave an IC50 value of 0.107 mg/mL, which is like that observed in this study for A. diaperinus PE hydrolysates with artichoke enzyme extract. However, the A. diaperinus hydrolysate with 2.5 L alcalase showed an IC50 value of 0.056 mg/mL, indicating a higher ACE-inhibitory activity [37]. Furthermore, artichoke enzyme extracts have been used to obtain hydrolysates with ACE-inhibitory activity from bovine casein and ovalbumin (Table 3). Thus, the ACE inhibition of the casein hydrolysates was like that observed in A. diaperinus PE hydrolysates here (IC50 of 117.04 vs. 111.33 µg peptides/mL, respectively). However, the ovalbumin hydrolysates from artichoke extract presented a higher ACE inhibition (IC50: 69.55 µg peptides/mL) than given by A. diaperinus PE hydrolysates.

4.3. Identification of Bioactive Peptides

Most peptides identified in both hydrolysates had a molecular weight <3 kDa and sequence chains between 8 and 20 amino acids. Authors have reported that these peptides have a low mass, yield a greater antioxidant activity [38] and ACE inhibition, because they accommodate more efficiently to the ACE active site [39]. In addition, the bioactivity of the peptides highly depends on their sequence and amino acid composition [40]. Thus, the presence of Pro, Gly, Ala, Val, and Leu confers intrinsic antioxidant activity [41]. In both hydrolysates in this study, many peptides containing these antioxidant residues were observed, some being <1.5 kDa and having over 50% of hydrophobic amino acids (Table 1 and Table 2). Therefore, the presence of Phe, Ile, Leu, Val, Ala, and Lys amino acids at the C- and N-termini is reported to improve the radical scavenging ability of the peptides [42]. The peptides 1, 2, 5, 6, and 8–20 of the LF hydrolysate, and the peptides 1–5 of the PE hydrolysate, present these hydrophobic residues at the N-terminus and/or C-terminus. Besides, in these peptides, these hydrophobic residues are present more frequently in the C-termini, which is reported to exert a greater antioxidant effect than when they are presented in N-termini [43,44]. Moreover, bulky hydrophobic amino acids with low electronic or steric/hydrogen bonding properties, such as Trp, Tyr, Phe, Met, Leu, and Ile, at the third position next to the C-terminus, contribute to the antioxidant activity [43]. Furthermore, the presence of glutamic and aspartic acids (Glu and Asp) may be responsible for the antioxidant properties [45]. Therefore, many peptides from LF hydrolysate, such as GLIGAPIAAPI, AESEVAALNR, VDAAVLEKLEA, FSLPHAILRLDL, and YALPHAILRIDL, as well as peptides from PE hydrolysate, such as APVAVAHAAAVPA, ASVVEKLLGDY, and GLIGAPIAAPIAA, presented over one of these antioxidant characteristics. The peptide VDAAVLEKLEA of the LF hydrolysate attracted our attention, because it contains 63.64% hydrophobic amino acids, with Val and Ala at the N- and C-termini, respectively, as well as a bulky hydrophobic amino acid (Leu) at the third position next to the C-terminus, and including glutamic and aspartic acids in its sequence. Regarding these results, the peptides with these particular structures could be responsible for the antioxidant capacities of the LF and its PE hydrolysates.

Considering the in vitro ACE-inhibitory activity of the PE hydrolysate and the peptide sequences identified, it has been reported that C-terminal tripeptide residues play a predominant role in competitive binding to the active site of ACE. Studies indicated that this enzyme prefers substrates containing hydrophobic amino acid residues (aromatic or branched side chains) at each of the three C-terminal positions [1]. APVAVAHAAVPA, GLIGAPIAAPIAA, and LEKDNALDRAAM share this characteristic. Furthermore, the most effective ACE-inhibitory peptides identified contain Tyr, Phe, Trp, and/or Pro at the C-terminus [1], such as ASVVEKLGDY.

Regarding the normalized quantification of all possible bioactive sequence fragments within the primary structure of the identified peptides, the LF hydrolysate contained more sequence fragments with putative antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory activities (979,440 and 4,183,560, respectively). These results agree with the determination of antioxidant activity against DPPH in vitro in this study.

However, there are several studies of insect protein hydrolysates that have reported peptide sequences that showed bioactivity. Zhu et al., in solitary black fly (Hermetia illucens L.) hydrolysate with alcalase, identified several peptides (PTTAPSATIN, MAAGTNLLDTK, FPGGETEALRR, AGGGGGGGGGGGKNL, IHKAGGGGGGGGGGGK, NWDLKEVGGGALP, SATTAIYMNALL, and SLGEMKQTAK) comprising over 50% of hydrophobic amino acids which are related to high antioxidant capacity [46]. Pattarayingsakul et al. identified peptides derived from pepsin and trypsin digestion of Oecophylla smaragdina with high ACE-inhibitory capacity (FFGT and LSRVP) and elevated antioxidant activity (CTKKHKPNC) [47]. Furthermore, bioactive peptides were also identified from other food protein hydrolysates obtained from C. scolymus enzyme extract. Bueno Gavilá et al. reported 22 bioactive peptides in bovine casein hydrolysates, GPVRGPFPII; KVLPVPQK; ARHPHPKLSFM; and VKEAMAPK, with antioxidant activity, and TPVVVPPFLQP with ACE-inhibitory activity [34]. Furthermore, in ovalbumin hydrolysates from artichoke enzyme extract, peptides with antioxidant activity (IAAEVYEHTEGSTTSY and PIAAEVYEHTEGSTTSY) and with ACE-inhibitory activity (HLFGPPGKKDPV and YAEERYPIL) were reported [8].

5. Conclusions

In this study, A. diaperinus larvae hydrolysates obtained with artichoke enzyme extracts have demonstrated antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory activities in vitro. The antioxidant capacity was higher in the raw larvae hydrolysate compared to the protein extract hydrolysate, probably due to the presence of other compounds with antioxidant properties besides peptides. The analytical results agree with the potential bioactivity of the peptide sequences identified in both hydrolysates. Therefore, artichoke enzyme extract could be used to obtain multifunctional hydrolysates from insect protein that could be incorporated into future functional foods.

This study shows that an agricultural residue of great economic importance could be revalorized, providing a sustainable and more environmentally friendly source of protein. However, additional studies involving antihypertensive and antioxidant activities in vivo and potential cytotoxicity effects are required.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T., J.M.C. and A.A.; methodology, L.T., E.B.-G. and I.H.; software, L.T.; validation, L.T. and E.B.-G.; formal analysis, L.T., E.B.-G. and I.H.; investigation, I.H., L.T., E.S., L.B.-M. and E.B.-G.; data curation, L.T. and E.B.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.H., L.T., L.B.-M. and E.B.-G.; writing—review and editing, L.B.-M. and E.B.-G.; visualization, E.B.-G.; supervision, L.T.; project administration, J.M.C.; funding acquisition, L.T. and J.M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Industry of the Region of Murcia, grant number RIS3MUR: Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialization.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Séneca Foundation (Science and Technology Agency of Murcia Region) for the “call for the regional subprogram for hiring postdoctoral researchers and innovation managers in Universities and public research organizations in the Region of Murcia”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hernández-Ledesma, B.; del Mar Contreras, M.; Recio, I. Antihypertensive Peptides: Production, Bioavailability and Incorporation into Foods. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 165, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Manzoor, M.; Singh, J.; Gani, A. Exploration of Bioactive Peptides from Various Origin as Promising Nutraceutical Treasures: In Vitro, in Silico and in Vivo Studies. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercruysse, L.; Smagghe, G.; Beckers, T.; Camp, J.V. Antioxidative and ACE Inhibitory Activities in Enzymatic Hydrolysates of the Cotton Leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Vital, D.A.; Mojica, L.; de Mejía, E.G.; Mendoza, S.; Loarca-Piña, G. Biological Potential of Protein Hydrolysates and Peptides from Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): A Review. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Gavilá, E.; Abellán, A.; Bermejo, M.S.; Salazar, E.; Cayuela, J.M.; Prieto-Merino, D.; Tejada, L. Characterization of Proteolytic Activity of Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) Flower Extracts on Bovine Casein to Obtain Bioactive Peptides. Animals 2020, 10, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, R.J.; Murray, B.A.; Walsh, D.J. Hypotensive Peptides from Milk Proteins. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 980S–988S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gobbetti, M.; Stepaniak, L.; De Angelis, M.; Corsetti, A.; Di Cagno, R. Latent Bioactive Peptides in Milk Proteins: Proteolytic Activation and Significance in Dairy Processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 42, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Gavilá, E.; Abellán, A.; Girón-Rodríguez, F.; Cayuela, J.M.; Tejada, L. Bioactivity of Hydrolysates Obtained from Chicken Egg Ovalbumin Using Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) Proteases. Foods 2021, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetsuna, K.; Chen, J.-R. Identification of Antihypertensive Peptides from Peptic Digest of Two Microalgae, Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulina platensis. Mar. Biotechnol. 2001, 3, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yust, M.M.; Pedroche, J.; Giron-Calle, J.; Alaiz, M.; Millán, F.; Vioque, J. Production of ACE Inhibitory Peptides by Digestion of Chickpea Legumin with Alcalase. Food Chem. 2003, 81, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huis, A.; Van Itterbeeck, J.; Klunder, H.; Mertens, E.; Halloran, A.; Muir, G.; Vantomme, P. Edible Insects: Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bednářová, M.; Borkovcová, M.; Mlček, J.; Rop, O.; Zeman, L. Edible Insects-Species Suitable for Entomophagy under Condition of Czech Republic. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2013, 61, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Testa, M.; Stillo, M.; Maffei, G.; Andriolo, V.; Gardois, P.; Zotti, C.M. Ugly but Tasty: A Systematic Review of Possible Human and Animal Health Risks Related to Entomophagy. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3747–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/893 24 May 2017 Amending Annexes I and IV to Regulation (EC) No 999/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Annexes X, XIV and XV to Commission Regulation (EU) No 142/2011 as Regards the Provisions on Processed Animal Protein (Text with EEA Relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2017, 138, 92–116.

- Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on Novel Foods, Amending Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 258/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1852/2001 (Text with EEA Relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2015, 327, 1–12.

- Nongonierma, A.B.; FitzGerald, R.J. Unlocking the Biological Potential of Proteins from Edible Insects through Enzymatic Hydrolysis: A Review. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 43, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, Y.; Shukla, P.; Singh, P.; Prabhakaran, P.P.; Tanwar, V.K. Bio-Plastics. A Perfect Tool for Eco-Friendly Food Packaging: A Review. J. Food Prod. Dev. Packag. 2014, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Z.; Ma, J.I.; Yang, J. Expression and Characterization of CecropinXJ, a Bioactive Antimicrobial Peptide from Bombyx mori (Bombycidae, Lepidoptera) in Escherichia coli. Exp. Ther. Med. 2013, 5, 1745–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vercruysse, L.; Smagghe, G.; Herregods, G.; Van Camp, J. ACE Inhibitory Activity in Enzymatic Hydrolysates of Insect Protein. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 5207–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, F.; Johnson, P.E.; Liceaga, A. Effect of Enzymatic Hydrolysis on Bioactive Properties and Allergenicity of Cricket (Gryllodes sigillatus) Protein. Food Chem. 2018, 262, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leni, G.; Soetemans, L.; Jacobs, J.; Depraetere, S.; Gianotten, N.; Bastiaens, L.; Caligiani, A.; Sforza, S. Protein Hydrolysates from Alphitobius diaperinus and Hermetia illucens Larvae Treated with Commercial Proteases. J. Insects Food Feed 2020, 6, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Zhao, X.; Kuang, Z.; Ye, M.; Luo, G.; Xiao, G.; Liao, S.; Li, L.; Xiong, Z. Optimization of Antioxidant Peptide Production in the Hydrolysis of Silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) Pupa Protein Using Response Surface Methodology. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11, 952–956. [Google Scholar]

- Zielińska, E.; Karaś, M.; Jakubczyk, A. Antioxidant Activity of Predigested Protein Obtained from a Range of Farmed Edible Insects. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.; Pissarra, J.; Veríssimo, P.; Castanheira, P.; Costa, Y.; Pires, E.; Faro, C. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of CDNA Encoding Cardosin B, an Aspartic Proteinase Accumulating Extracellularly in the Transmitting Tissue of Cynara cardunculus L. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 45, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tejada, L.; Abellán, A.; Cayuela, J.M.; Martínez-Cacha, A.; Fernández-Salguero, J. Proteolysis in Goats’ Milk Cheese Made with Calf Rennet and Plant Coagulant. Int. Dairy J. 2008, 18, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkiewicz, P.; Dziuba, J.; Iwaniak, A.; Dziuba, M.; Darewicz, M. BIOPEP Database and Other Programs for Processing Bioactive Peptide Sequences. J. AOAC Int. 2008, 91, 965–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tejada, L.; Fernandez-Salguero, J. Chemical and Microbiological Characteristics of Ewe Milk Cheese (Los Pedroches) Made with a Powdered Vegetable Coagulant or Calf Rennet. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2003, 15, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.Y.; Jia, J.Q.; Tan, G.X.; Xu, J.L.; Gui, Z.Z. Physicochemical Properties of Silkworm Larvae Protein Isolate and Gastrointestinal Hydrolysate Bioactivities. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 6145–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Methods of Analysis, 21st Edition. 2019. Available online: https://www.aoac.org/official-methods-of-analysis-21st-edition-2019/ (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Timón, M.L.; Parra, V.; Otte, J.; Broncano, J.M.; Petrón, M.J. Identification of Radical Scavenging Peptides (<3 kDa) from Burgos-Type Cheese. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 57, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersuder, P.; Hole, M.; Smith, G. Antioxidants from Heated Histidine-Glucose Model System. I: Investigation of the Antioxidant Role of Histidine and Isolation of Antioxidants by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1998, 75, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.; Recio, I.; Gómez-Ruiz, J.A.; Ramos, M.; López-Fandiño, R. Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Peptides Derived from Egg White Proteins by Enzymatic Hydrolysis. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 1914–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno-Gavilá, E.; Abellán, A.; Girón-Rodríguez, F.; Cayuela, J.M.; Salazar, E.; Gómez, R.; Tejada, L. Bioactivity of Hydrolysates Obtained from Bovine Casein Using Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) Proteases. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 10711–10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Debnath, T.; Choi, E.-J.; Kim, Y.W.; Ryu, J.P.; Jang, S.; Chung, S.U.; Choi, Y.-J.; Kim, E.-K. Changes in the Amino Acid Profiles and Free Radical Scavenging Activities of Tenebrio molitor Larvae Following Enzymatic Hydrolysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Jia, J.; Yan, H.; Du, J.; Gui, Z. A Novel Angiotensin-I Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Peptide from Gastrointestinal Protease Hydrolysate of Silkworm Pupa (Bombyx mori) Protein: Biochemical Characterization and Molecular Docking Study. Peptides 2015, 68, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, P.; Borges, S.; Pintado, M. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Insect Alphitobius diaperinus towards the Development of Bioactive Peptide Hydrolysates. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 3539–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Z.-J.; Jung, W.-K.; Kim, S.-K. Free Radical Scavenging Activity of a Novel Antioxidative Peptide Purified from Hydrolysate of Bullfrog Skin, Rana Catesbeiana Shaw. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1690–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natesh, R.; Schwager, S.L.U.; Sturrock, E.D.; Acharya, K.R. Crystal Structure of the Human Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme–Lisinopril Complex. Nature 2003, 421, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Ruan, G.; Qin, Z.; Li, H.; Zheng, Y. Antioxidant Activity Measurement and Potential Antioxidant Peptides Exploration from Hydrolysates of Novel Continuous Microwave-Assisted Enzymolysis of the Scomberomorus Niphonius Protein. Food Chem. 2017, 223, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanasiritham, L.; Theerakulkait, C.; Wickramasekara, S.; Maier, C.S.; Stevens, J.F. Isolation and Identification of Antioxidant Peptides from Enzymatically Hydrolyzed Rice Bran Protein. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzadehpanah, H.; Asoodeh, A.; Chamani, J. An Antioxidant Peptide Derived from Ostrich (Struthio Camelus) Egg White Protein Hydrolysates. Food Res. Int. 2012, 49, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-W.; Li, B. Characterization of Structure–Antioxidant Activity Relationship of Peptides in Free Radical Systems Using QSAR Models: Key Sequence Positions and Their Amino Acid Properties. J. Theor. Biol. 2013, 318, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Jin, D.-H.; Ogawa, T.; Muramoto, K.; Hatakeyama, E.; Yasuhara, T.; Nokihara, K. Antioxidative Properties of Tripeptide Libraries Prepared by the Combinatorial Chemistry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3668–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiga, A.; Tanabe, S.; Nishimura, T. Antioxidant Activity of Peptides Obtained from Porcine Myofibrillar Proteins by Protease Treatment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3661–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Huang, X.; Tu, F.; Wang, C.; Yang, F. Preparation, Antioxidant Activity Evaluation, and Identification of Antioxidant Peptide from Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens L.) Larvae. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattarayingsakul, W.; Nilavongse, A.; Reamtong, O.; Chittavanich, P.; Mungsantisuk, I.; Mathong, Y.; Prasitwuttisak, W.; Panbangred, W. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory and Antioxidant Peptides from Digestion of Larvae and Pupae of Asian Weaver Ant, Oecophylla smaragdina, Fabricius. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 3133–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).