miRNA-Profiling in Ejaculated and Epididymal Pig Spermatozoa and Their Relation to Fertility after Artificial Insemination

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Boars Handling and Sample Collection

2.4. RNA Extraction

2.5. Small RNA Library Preparation

2.6. Overview of Sequencing Performance

2.7. Bioinformatic Analyses

2.8. Target Gene Prediction and Functional Analysis

3. Results

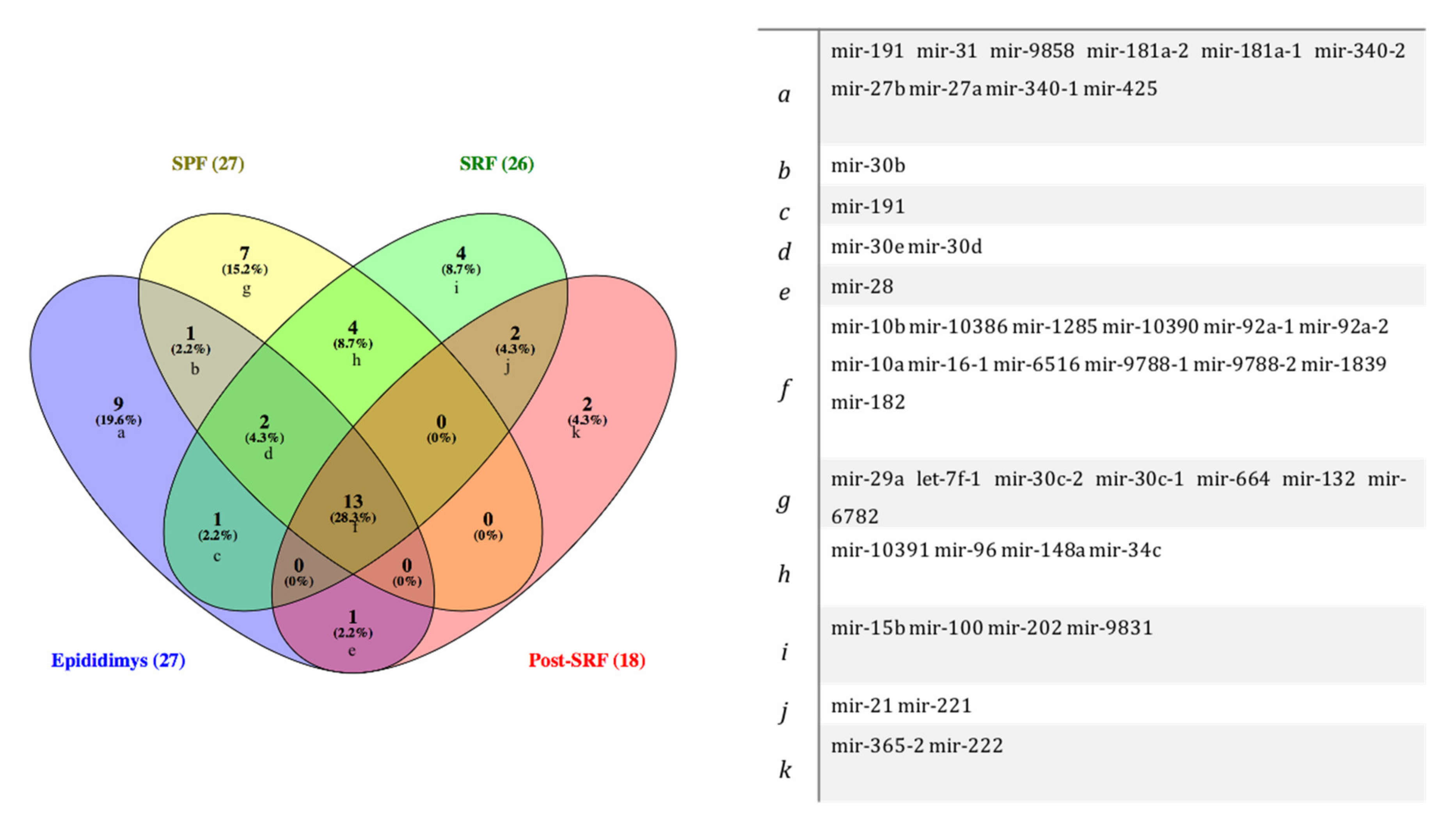

3.1. Identification of miRNAs in Spermatozoa from Cauda Epididymis and Ejaculate Fractions

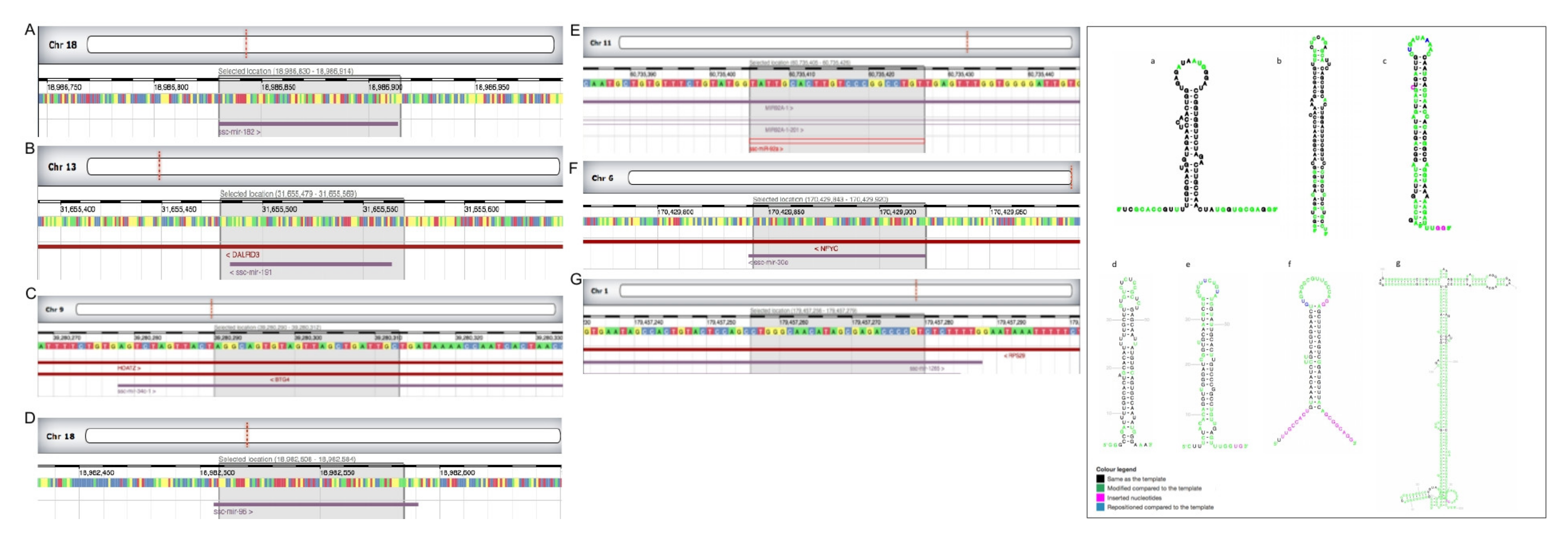

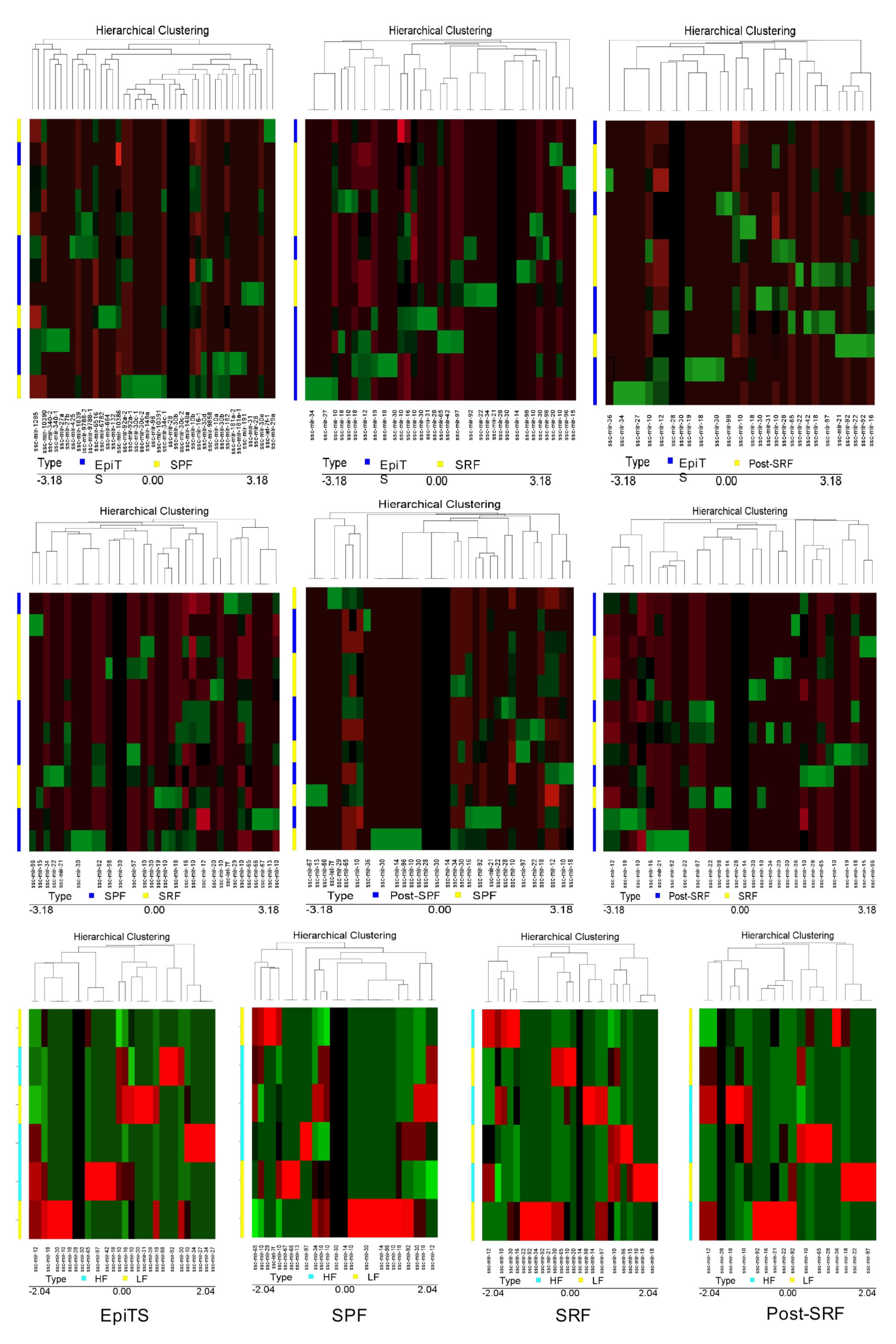

3.2. miRNAs Were Differentially Expressed among Spermatozoa Ejaculate Fractions and from Cauda Epididymis, as Well as between Boars with Higher (HF) or Lower (LF) Fertility: Assessment of Chromosome Location and Structure

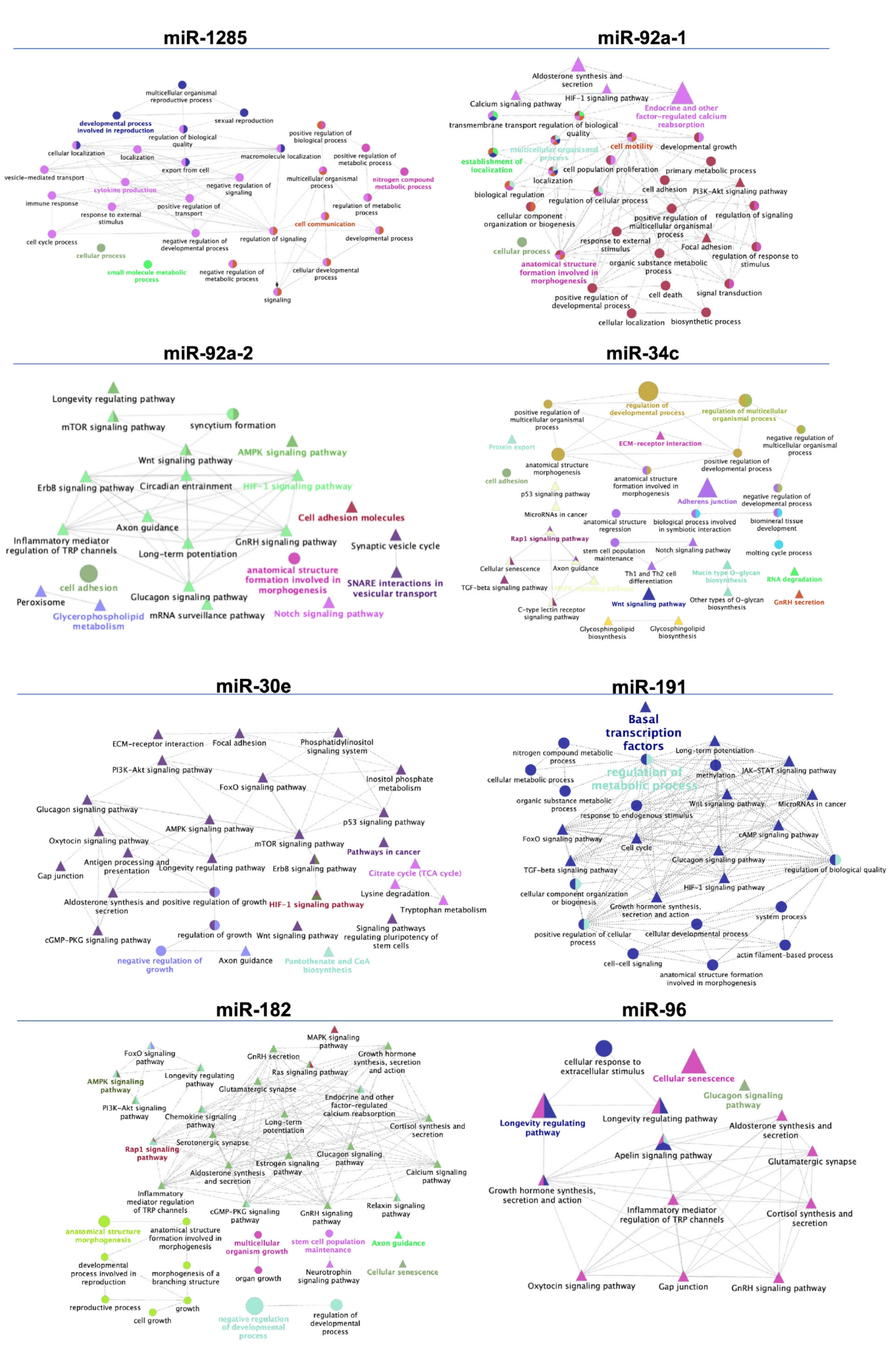

3.3. Target Prediction and Functional Annotations of Differentially Expressed Sperm miRNAs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Visconti, P.E.; Stewart-Savage, J.; Blasco, A.; Battaglia, L.; Miranda, P.; Kopf, G.S.; Tezon, J.G. Roles of bicarbonate, cAMP, and protein tyrosine phosphorylation on capacitation and the spontaneous acrosome reaction of hamster sperm. Biol. Reprod. 1999, 61, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donlic, A.; Hargrove, A.E. Targeting RNA in mammalian systems with small molecules. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2018, 9, e1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Fan, P.; Wang, L.; Shu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Feng, S.; Li, X.; Qiu, X.; Zhao, S.; Liu, X. Improvement, identification, and target prediction for miRNAs in the porcine genome by using massive, public high-throughput sequencing data. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, R.; Wang, Y.; Lian, W.; Li, W.; Xi, Y.; Xue, S.; Kang, T.; Lei, M. Small RNA-seq analysis of extracellular vesicles from porcine uterine flushing fluids during peri-implantation. Gene 2021, 766, 145117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausser, J.; Syed, A.P.; Bilen, B.; Zavolan, M. Analysis of CDS-located miRNA target sites suggests that they can effectively inhibit translation. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, S.; Bracht, J.; Hunter, S.; Massirer, K.; Holtz, J.; Eachus, R.; Pasquinelli, A.E. Regulation by let-7 and lin-4 miRNAs results in target mRNA degradation. Cell 2005, 122, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Fan, J.; Belasco, J.G. MicroRNAs direct rapid deadenylation of mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 4034–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, S.; Tong, Y.; Steitz, J.A. Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science 2007, 318, 1931–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Analysis and significance of messenger RNA in human ejaculated spermatozoa. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2000, 56, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Morozumi, K.; Zhang, J.; Ro, S.; Park, C.; Yanagimachi, R. Birth of mice after intracytoplasmic injection of single purified sperm nuclei and detection of messenger RNAs and MicroRNAs in the sperm nuclei. Biol. Reprod. 2008, 78, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, E.; Ellis, S.E.; Pratt, S.L. Detection of porcine sperm microRNAs using a heterologous microRNA microarray and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 76, 218–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanai, M.; Brahmajosyula, M.; Perry, A.C.F. A restricted role for sperm-borne microRNAs in mammalian fertilization. Biol. Reprod. 2006, 75, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.-M.; Pang, R.T.K.; Chiu, P.C.n.; Wong, B.P.C.; Lao, K.; Lee, K.-F.; Yeung, W.S.B. Sperm-borne microRNA-34c is required for the first cleavage division in mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Blondin, P.; Vigneault, C.; Labrecque, R.; Sirard, M.-A. Sperm miRNAs—Potential mediators of bull age and early embryo development. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.B.R.; de Arruda, R.P.; De Bem, T.H.C.; Florez-Rodriguez, S.A.; de Sá Filho, M.F.; Belleannée, C.; Meirelles, F.V.; da Silveira, J.C.; Perecin, F.; Celeghini, E.C.C. Sperm-borne miR-216b modulates cell proliferation during early embryo development via K-RAS. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maatouk, D.M.; Loveland, K.L.; McManus, M.T.; Moore, K.; Harfe, B.D. Dicer1 is required for differentiation of the mouse male germline. Biol. Reprod. 2008, 79, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, Q.; Feng, T.; Zhang, P.; Liao, M.; Tian, X.; Lu, H.; Zeng, W. Profiling of miRNAs in porcine Sertoli cells. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, A.M.M.T.; Choi, Y.-J.; Han, S.G.; Song, H.; Park, C.; Hong, K.; Kim, J.-H. Roles of microRNAs in mammalian reproduction: From the commitment of germ cells to peri-implantation embryos. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimanickam, V.; Buhr, M.; Kasimanickam, R. Patterns of expression of sperm and seminal plasma microRNAs in boar semen. Theriogenology 2019, 125, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Martinez, H. Aspects of the Electrolytic Composition of Boar Epididymal Fluid with Reference to Sperm Maturation and Storage, Boar Semen Preservation II. In Reproduction in Domestic Animals; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991; Volume 57, pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Dai, D.-H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, G.-B.; Zeng, C.-J. Differences in the expression of microRNAs and their predicted gene targets between cauda epididymal and ejaculated boar sperm. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 2162–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, H.; Shen, D.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Gao, B.; Wu, T.; Li, B.; Li, K.; et al. Comparative profiling of small RNAs of pig seminal plasma and ejaculated and epididymal sperm. Reproduction 2017, 153, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, H.; Kvist, U.; Saravia, F.; Wallgren, M.; Johannisson, A.; Sanz, L.; Peña, F.J.; Martínez, E.A.; Roca, J.; Vázquez, J.M.; et al. The physiological roles of the boar ejaculate. Soc. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 2009, 66, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, H.; Saravia, F.; Wallgren, M.; Tienthai, P.; Johannisson, A.; Vázquez, J.M.; Martínez, E.; Roca, J.; Sanz, L.; Calvete, J.J. Boar spermatozoa in the oviduct. Theriogenology 2005, 63, 514–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, S.H.A.; Kaster, N.; Khan, R.; Abdelnour, S.A.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; Khafaga, A.F.; Taha, A.; Ohran, H.; Swelum, A.A.; Schreurs, N.M.; et al. The Role of MicroRNAs in Muscle Tissue Development in Beef Cattle. Genes 2020, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, A.W.Y.; Pang, R.T.K.; Liu, W.-M.; Kottawatta, K.S.A.; Lee, K.-F.; Yeung, W.S.B. MicroRNA Let-7a and dicer are important in the activation and implantation of delayed implanting mouse embryos. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wu, Z.; Ma, C.; Pan, N.; Wang, Y.; Yan, L. Endometrial miR-543 Is Downregulated During the Implantation Window in Women with Endometriosis-Related Infertility. Reprod. Sci. 2019, 26, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Martinez, H.; Roca, J.; Alvarez-Rodriguez, M.; Martinez-Serrano, C.A. How does the boar epididymis regulate the emission of fertile spermatozoa? Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 106829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barranco, I.; Perez-Patiño, C.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Parrilla, I.; Vicente-Carrillo, A.; Alvarez-Rodriguez, M.; Ceron, J.J.; Martinez, E.A.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H.; Roca, J. Active paraoxonase 1 is synthesised throughout the internal boar genital organs. Reproduction 2017, 154, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, C.; Hardin, J.; Stoebel, D.M. Selecting between-sample RNA-Seq normalization methods from the perspective of their assumptions. Brief. Bioinform. 2018, 19, 776–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.-P.; Hu, H.; Lei, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yao, B.; Chen, L.; Liang, G.; Zhan, S.; Zhu, X.; et al. Sperm microRNAs confer depression susceptibility to offspring. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Song, R.; Ortogero, N.; Zheng, H.; Evanoff, R.; Small, C.L.; Griswold, M.D.; Namekawa, S.H.; Royo, H.; Turner, J.M.; et al. The RNase III enzyme DROSHA is essential for microRNA production and spermatogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 25173–25190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolstad, B.M.; Irizarry, R.A.; Astrand, M.; Speed, T.P. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvari, I.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Ontiveros-Palacios, N.; Argasinska, J.; Lamkiewicz, K.; Marz, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S.; Toffano-Nioche, C.; Gautheret, D.; Weinberg, Z.; et al. Rfam 14: Expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microRNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D192–D200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, B.A.; Hoksza, D.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Ribas, C.E.; Madeira, F.; Cannone, J.J.; Gutell, R.; Maddala, A.; Meade, C.D.; Williams, L.D.; et al. R2DT is a framework for predicting and visualising RNA secondary structure using templates. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, E.; Safranski, T.J.; Pratt, S.L. Differential expression of porcine sperm microRNAs and their association with sperm morphology and motility. Theriogenology 2011, 76, 1532–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleannée, C.; Calvo, É.; Caballero, J.; Sullivan, R. Epididymosomes convey different repertoires of microRNAs throughout the bovine epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 2013, 89, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.N.; McLaughlin, E.A.; Stanger, S.J.; Anderson, A.L.; Hutcheon, K.; Church, K.; Mihalas, B.P.; Tyagi, S.; Holt, J.E.; Eamens, A.L.; et al. Characterisation of mouse epididymosomes reveals a complex profile of microRNAs and a potential mechanism for modification of the sperm epigenome. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Sun, F.; Conine, C.C.; Reichholf, B.; Kukreja, S.; Herzog, V.A.; Ameres, S.L.; Rando, O.J. Small RNAs Are Trafficked from the Epididymis to Developing Mammalian Sperm. Dev. Cell 2018, 46, 481–494.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.S.; Johannisson, A.; Siqueira, A.P.; Wallgren, M.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H. Spermatozoa in the sperm-peak-fraction of the boar ejaculate show a lower flow of Ca(2+) under capacitation conditions post-thaw which might account for their higher membrane stability after cryopreservation. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 128, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pawlina, K.; Gurgul, A.; Oczkowicz, M.; Bugno-Poniewierska, M. The characteristics of the porcine (Sus scrofa) liver miRNAome with the use of next generation sequencing. J. Appl. Genet. 2015, 56, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Xi, Q.-Y.; Ye, R.-S.; Cheng, X.; Qi, Q.-E.; Wang, S.-B.; Shu, G.; Wang, L.-N.; Zhu, X.-T.; Jiang, Q.-Y.; et al. Exploration of microRNAs in porcine milk exosomes. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plé, H.; Landry, P.; Benham, A.; Coarfa, C.; Gunaratne, P.H.; Provost, P. The repertoire and features of human platelet microRNAs. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Liao, J.-Y.; Guan, D.-G.; Yang, J.-H.; Zheng, L.-L.; Jing, Q.; Zhou, H.; Qu, L.-H. Drastic expression change of transposon-derived piRNA-like RNAs and microRNAs in early stages of chicken embryos implies a role in gastrulation. RNA Biol. 2012, 9, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inukai, S.; de Lencastre, A.; Turner, M.; Slack, F. Novel microRNAs differentially expressed during aging in the mouse brain. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Rodriguez, M.; Martinez, C.; Wright, D.; Barranco, I.; Roca, J.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H. The Transcriptome of Pig Spermatozoa, and Its Role in Fertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, M.D.; Nef, S. microRNAs in the testis: Building up male fertility. J. Androl. 2010, 31, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.J.; Yi, W.; Rong, Y.W.; Kee, J.D.; Zhong, W.X. MicroRNA-1285 Regulates 17β-Estradiol-Inhibited Immature Boar Sertoli Cell Proliferation via Adenosine Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase Activation. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 4059–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.C.-L.; Chen, H.-Y.; Lin, Y.-W.; Chu, W.-C.; Lin, M.-J.; Yan, Y.-T.; Yen, P.H. DAZAP1, an hnRNP protein, is required for normal growth and spermatogenesis in mice. RNA 2008, 14, 1814–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Fu, W.; Fu, K.; Liu, G.; Jia, W. MicroRNA-92a-3p inhibits the cell proliferation, migration and invasion of Wilms tumor by targeting NOTCH1. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Antonellis, P.; Medaglia, C.; Cusanelli, E.; Andolfo, I.; Liguori, L.; De Vita, G.; Carotenuto, M.; Bello, A.; Formiggini, F.; Galeone, A.; et al. MiR-34a targeting of Notch ligand delta-like 1 impairs CD15+/CD133+ tumor-propagating cells and supports neural differentiation in medulloblastoma. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corney, D.C.; Flesken-Nikitin, A.; Godwin, A.K.; Wang, W.; Nikitin, A.Y. MicroRNA-34b and MicroRNA-34c are targets of p53 and cooperate in control of cell proliferation and adhesion-independent growth. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8433–8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lujambio, A.; Calin, G.A.; Villanueva, A.; Ropero, S.; Sánchez-Céspedes, M.; Blanco, D.; Montuenga, L.M.; Rossi, S.; Nicoloso, M.S.; Faller, W.J.; et al. A microRNA DNA methylation signature for human cancer metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13556–13561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumamoto, K.; Spillare, E.A.; Fujita, K.; Horikawa, I.; Yamashita, T.; Appella, E.; Nagashima, M.; Takenoshita, S.; Yokota, J.; Harris, C.C. Nutlin-3a activates p53 to both down-regulate inhibitor of growth 2 and up-regulate mir-34a, mir-34b, and mir-34c expression, and induce senescence. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 3193–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommer, G.T.; Gerin, I.; Feng, Y.; Kaczorowski, A.J.; Kuick, R.; Love, R.E.; Zhai, Y.; Giordano, T.J.; Qin, Z.S.; Moore, B.B.; et al. p53-mediated activation of miRNA34 candidate tumor-suppressor genes. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 1298–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscherner, A.; Gilchrist, G.; Smith, N.; Blondin, P.; Gillis, D.; LaMarre, J. MicroRNA-34 family expression in bovine gametes and preimplantation embryos. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2014, 12, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantos, K.; Grigoriadis, S.; Tomara, P.; Louka, I.; Maziotis, E.; Pantou, A.; Nitsos, N.; Vaxevanoglou, T.; Kokkali, G.; Agarwal, A.; et al. Investigating the Role of the microRNA-34/449 Family in Male Infertility: A Critical Analysis and Review of the Literature. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisin, A.; Damon-Soubeyrand, C.; Bravard, S.; Saez, F.; Drevet, J.R.; Guiton, R. Differential expression and localisation of TGF-β isoforms and receptors in the murine epididymis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.A.; Rubér, M.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H.; Alvarez-Rodriguez, M. Pig Pregnancies after Transfer of Allogeneic Embryos Show a Dysregulated Endometrial/Placental Cytokine Balance: A Novel Clue for Embryo Death? Biomolecules 2020, 10, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhuish, T.A.; Gallo, C.M.; Wotton, D. TGIF2 interacts with histone deacetylase 1 and represses transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 32109–32114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumder, S.; Bhowal, A.; Basu, S.; Mukherjee, P.; Chatterji, U.; Sengupta, S. Deregulated E2F5/p38/SMAD3 Circuitry Reinforces the Pro-Tumorigenic Switch of TGFβ Signaling in Prostate Cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 2482–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamonde, M.E.; Lyons, K.M. BMP3: To be or not to be a BMP. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2001, 83, S56–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Martinez, H.; Kvist, U.; Ernerudh, J.; Sanz, L.; Calvete, J.J. Seminal plasma proteins: What role do they play? Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011, 66 (Suppl S1), 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbluth, E.M.; Shelton, D.N.; Wells, L.M.; Sparks, A.E.T.; Van Voorhis, B.J. Human embryos secrete microRNAs into culture media-a potential biomarker for implantation. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegh, A.H.; Kim, H.; Bachoo, R.M.; Forloney, K.L.; Zhang, J.; Schulze, H.; Park, K.; Hannon, G.J.; Yuan, J.; Louis, D.N.; et al. Bcl2L12 inhibits post-mitochondrial apoptosis signaling in glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedemann, J.; Macaulay, V.M. IGF1R signalling and its inhibition. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2006, 13 (Suppl. S1), S33–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisinger, A.; Alsheimer, M.; Baier, A.; Benavente, R.; Wettstein, R. The mammalian gene pecanex 1 is differentially expressed during spermatogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Struct. Expr. 2005, 1728, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Long, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. Identification and characterization of miR-96, a potential biomarker of NSCLC, through bioinformatic analysis. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Sharma, R.; Samanta, L.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Sabanegh, E. Proteomic signatures of infertile men with clinical varicocele and their validation studies reveal mitochondrial dysfunction leading to infertility. Asian J. Androl. 2016, 18, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eppig, J.T.; Blake, J.A.; Bult, C.J.; Kadin, J.A.; Richardson, J.E. The Mouse Genome Database (MGD): Facilitating mouse as a model for human biology and disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D726–D736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korfanty, J.; Stokowy, T.; Chadalski, M.; Toma-Jonik, A.; Vydra, N.; Widłak, P.; Wojtaś, B.; Gielniewski, B.; Widlak, W. SPEN protein expression and interactions with chromatin in mouse testicular cells. Reproduction 2018, 156, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sujit, K.M.; Sarkar, S.; Singh, V.; Pandey, R.; Agrawal, N.K.; Trivedi, S.; Singh, K.; Gupta, G.; Rajender, S. Genome-wide differential methylation analyses identifies methylation signatures of male infertility. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 2256–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Reads (n) | Pf Reads (%) | Reads >q30 (%) | Undetermined Reads (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Lanes 1–4 | 14,494,752 | 97.37 | 98.39 | 2.62 |

| Group | miRNAs (n) | Name of miRNAs |

|---|---|---|

| SPF | 27 | mir-182, mir-6516, mir-29a, mir-10386, mir-let-7f-1, mir-30c-2, mir-30b, mir-96, mir-148a, mir-92a-1, mir-92a-2, mir-30d, mir-10390, mir-9788-1, mir-9788-2, mir-1285, mir-34c-1, mir-30e, mir-30c-1, mir-10a, mir-10391, mir-1839, mir-10b, mir-664, mir-132, mir-6782, mir-16-1 |

| SRF | 26 | mir-9831, mir-148a, mir-96, mir-6516, mir-30e, mir-15b, mir-21, mir-221, mir-182, mir-1285, mir-100, mir-9788-1, mir-9788-2, mir-92a-1, mir-34c-1, mir-191, mir-1839, mir-10391, mir-10386, mir-10390, mir-202, mir-92a-2, mir-10a, mir-30d, mir-16-1, mir-10b |

| Post-SRF | 19 | mir-1285, mir-28, mir-10a, mir-221, mir-9788-1, mir-9788-2, mir-182, mir-365-2, mir-10386, mir-16-1, mir-1839, mir-10390, mir-6516, mir-92a-2, mir-92a-1, mir-10b, mir-21, mir-222, mir-30e |

| EpiTS | 27 | mir-92a-1, mir-9858, mir-191, mir-27a, mir-340-1, mir-16-1, mir-10386, mir-1285, mir-31, mir-92a-2, mir-30d mir-28, mir-30e, mir-10390, mir-181a-2, mir-181a-1, mir-10a, mir-10b, mir-30b, mir-340-2, mir-27b, mir-6516, mir-9788-1, mir-9788-2, mir-425, mir-1839, mir-182 |

| Group | Name of miRNAs Differentially Abundant | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|

| SPF vs. SRF | mir-34c, mir-92a-1, mir-92a-2 | 2.5, 4, 4.1 |

| SRF vs. Post-SRF | mir-30e | −1.2 |

| EpiTS vs. SPF | mir-1285 | 1.7 |

| EpiTS vs. SRF | mir-1285 | 1.6 |

| EpiTS vs. Post-SRF | mir-1285 | 1.8 |

| HF vs. LF SPF | mir-182 | 1.1 |

| HF vs. LF SRF | mir-96 | −3.3 |

| HF vs. LF Post-SRF | mir-1285 | 1.1 |

| HF vs. LF EpiTS | mir-191 | −3.1 |

| Comparison | miRNA | FC | Predicted Targets (n) | Name of Predicted Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPF vs. SRF | miR-92a-1 | 4 | 14 | SLX4 SH3TC2 LMLN NRP2 BCAM PRKCA ATN1 TOB1 ARMC7 ANKS1A SF3A3 ATP2B2 SLC2A1 COL1A1 |

| miR-92a-2 | 4.1 | 67 | IQSEC2 FOXP4 SYNGAP1 BCL7A FAM222A NFIX TOM1L2 HNF4A NKAIN1 DLK1 STX1B MIER2 ZBTB4 NACC1 APH1A SLC6A17 WNT1 AR CELF5 PPP2R5B RAMP2 KCNQ4 BCAM TGM2 FIBCD1 CELSR2 SLC4A1 NOVA2 ZNF574 PDE1B DNAJB5 ZNF385A ZSWIM4 TFE3 LRCH4 L1CAM MTA1 CLIP2 PPP1R9B GIPC1 EHMT2 B4GALNT1 COL5A3 TSC1 MLLT6 CAMTA1 DUSP3 FAM155B PBX2 SKI SMG5 RIMS3 CAMK2A PAPPA2 C12ORF43 NFIC SLC22A11 HYOU1 SLA2 TNRC6A DMPK SGCD NFASC GNPAT ZNF275 MOCS1 SLIT1 | |

| miR-34c | 2.5 | 85 | HCN3 FAM76A MDM DLL1 FKBP1B SYT1 E2F5 PPP1R11 RAP1GDS1 FAM167A SDK2 SATB2 SCN2B MYCN NECTIN1 CELF3 MGAT4A LGR4 NAV3 NAV1 MET FLOT2 XYLT1 AHCYL2 TGIF2 PACS1 PKP4 CACNA1E MLLT3 FUT9 RRAS PITPNC1 MPP2 VAMP2 ABR SLC25A27 FOXP1 CAMTA1 SRPRA MEX3C JAKMIP1 ELMOD1 TOB2 FUT8 LEF1 SHANK3 NPNT KIAA1217 GPR22 DAAM1 ASIC2 GALNT7 NUMBL TBL1XR1 BMP3 GABRA3 TNRC18 UBP1 PPARGC1B CUEDC1 ZMYM4 ARID4B FAM117B ATMIN CYREN HNF4A SFT2D1 CDK6 NRN1 EML5 SAR1A TMEM255A FOXN2 TASOR TPPP FGD6 PDE7B ADO ANK3 UNC13C LMAN1 CTNND2 POGZ KDM5D SNAI1 | |

| SPF vs. Post-SRF | miR-1285 | 1.1 | 18 | SORL1 AASDH ADGRG2 PDE4D PDCD6IP SGCB ANKRD17 SCP2 TWIST2 SNAP25 AFP DAZAP1 ZNF483 C8ORF58 GPBP1L1 ZNF454 PAX5 RFX7 |

| SRF vs. Post-SRF | miR-30e | −1.2 | 200 | ACTR3C ADAM19 ADAMTS3 ADAMTS9 ADRA2A ALG10 ANKHD1 ANKRA2 ANKRD17 ANO4 ASB3 ATG12 AZIN1 B3GNT5 BDP1 BRD1 BRWD1 BRWD3 C9orf72 CALCR CARF CCDC117 CCDC43 CCDC97 CCNE2 CCNT2 CELSR3 CFL2 CHD1 CHIC1 CHL1 CHST2 CLOCK CNKSR2 CNOT9 COL13A1 COL25A1 CYP24A1 DCTN4 DCUN1D3 DDAH1 DESI2 DLG5 DOLPP1 E2F7 EEA1 EED ELL2 EML1 EML4 EXTL2 FAM160B1 FAP FBXO45 FKBP3 FNDC3A FOXG1 FRMPD1 FRZB FZD3 GABRB1 GALNT7 GMNC GOLGA1 HCFC2 HDAC9 ITGA6 ITPK1 KIAA0408 KLF10 KLF12 KLHL20 KLHL28 LCLAT1 LHX8 LIMCH1 LIN28B LMBR1 LMBR1L LPGAT1 LRRC17 MARCH6 MAST4 MEIOB MEOX2 MIER3 MKRN3 MLXIP MTDH MYH11 NAV3 NCAM1 NECAP1 NEDD4 NEURL1B NFAT5 NFIB NT5E OTUD6B PAPOLA PCDH17 PDE7A PEX5L PFN2 PHIP PHTF2 PIP4K2A PLAGL2 PLEKHM3 PLEKHO2 PLPP6 PLPPR4 PNKD POLR3E PON2 PPARGC1B PPP1R2 PPP3R1 PRDM1 PRLR PRUNE2 PTGFRN PTP4A1 PTPN13 RAP2C RARG RASAL2 REEP3 RFX6 RFX7 RGS8 RIMBP2 ROR1 RORA RRAD RTKN2 RUNX1 RUNX2 S100PBP SAMD8 SCARA5 SCML1 SCN2A SCN3A SCN9A SEC22C SEC23A SEC24A SETD5 SH2B3 SH3PXD2A SIX1 SLC12A6 SLC35A3 SLC35C1 SMAD1 SNX16 SNX18 SOCS1 SOCS3 SOX SPEN SPOCK3 SRSF7 STAC STIM2 STK35 STK39STOX2 STX2 STXBP5 TBC1D10B TBL1XR1 TENT2 TLL2 TMEM170B TMEM181 TMEM56 TNIK TNRC6A TNRC6B TP53INP1 TWF1 UBE2J1 UBE2V2 UBN2 USP37 VIM WDR7 WDR82 XPO1 XPR1 YOD1 YPEL2 YTHDF3 ZBTB11 ZBTB41 ZCCHC2 ZMYND8 ZNRF1 |

| EpiTS vs. SPF | miR-1285 | 1.7 | 18 | SORL1 AASDH ADGRG2 PDE4D PDCD6IP SGCB ANKRD17 SCP2 TWIST2 SNAP25 AFP DAZAP1 ZNF483 C8ORF58 GPBP1L1 ZNF454 PAX5 RFX7 |

| EpiTS vs. SRF | miR-1285 | 1.6 | 18 | SORL1 AASDH ADGRG2 PDE4D PDCD6IP SGCB ANKRD17 SCP2 TWIST2 SNAP25 AFP DAZAP1 ZNF483 C8ORF58 GPBP1L1 ZNF454 PAX5 RFX7 |

| EpiTS vs. Post-SRF | miR-1285 | 1.8 | 18 | SORL1 AASDH ADGRG2 PDE4D PDCD6IP SGCB ANKRD17 SCP2 TWIST2 SNAP25 AFP DAZAP1 ZNF483 C8ORF58 GPBP1L1 ZNF454 PAX5 RFX7 |

| Comparison | miRNA | Predicted Targets (n) | Name of Predicted Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| HF- vs. LF-SPF | miR-182 | 98 | PRKACB RGS17 BNC2 SNX30 LPP MITF FRS2 CAMSAP2 HAS2 PRRG3 EPAS1 PALLD DCUN1D1 SLC39A9 VAMP3 MTSS1 NPTX1 NEXMIF CD2AP TECTB PRTG SPATA13 SPIN1 CACNB4 MFAP3 CTTN NCALD ACTR2 ABHD13 ADCY6 FOXF2 CADM2 TAF4B EDNRB RAB10 RAPGEF5 LRCH2 CHIC1 ZFP36L1 PCNX1 MAST4 ITPR1 RASA1 LMTK2 USP13 FOXO3 ZC3H15 MAGI1 TAGLN3 RARG LHX1 GNAQ LIMS1 GXYLT1 NRN1 STK19 IGF1R CBFA2T3 FLOT1 HOXA9 BRPF3 CUL5 FAM171A1 MED1 MYRIP TRABD2B PYGO2 PPM1L KIAA1217 HOOK3 SV2C BCL2L12 GIT2 BRMS1L PHIP TMEM47 MIGA1 FNDC3B BNIP3 ZFC3H1 INTS6 DCUN1D3 SLC35G1 PURA PPIL1 SERTAD4 EVI5 ADD3 L1CAM BMT2 STAG1 PLPPR4 ADGRL2 YWHAG HDAC9 ZNF280B RTN4 |

| HF- vs. LF-SRF | miR-96 | 73 | NEXMIF ADCY6 PRTG SPIN1 FRS2 LRCH2 HAS2 SH3BP5 BRPF3 JMJD1C SNX30 ATXN1 ITPR1 TBR1 PLPPR4 OXSR1 MTSS1 SLC1A1 COL25A1 UBE2G1 B4GALNT4 MED1 PHF20L1 KLHL34 VAMP3 SLAIN2 PHIP RAB8B CTTN E2F5 SOX6 ZFP36L1 SIN3B ZCCHC3 HOOK3 PALLD FOXF2 CHST1 MYRIP ZBTB41 FRMD5 CACNA2D2 PRKCE SH3KBP1 NOVA2 ZEB1 MTOR SLC39A1 PRRG3 TTYH3 NLGN2 FOXO1 ARHGAP6 ANKRD27 SESN3 CEP170B VAT1L PPP4R3A STAG1 CD164 UNC13C DOCK1 SPEN TMEM170B REV1 PPM1L NRN1 MIGA1 STK19 TMEM198 SPAST RGS17 EBF3 |

| HF- vs. LF-Post-SRF | miR-1285 | 18 | SORL1 AASDH ADGRG2 PDE4D PDCD6IP SGCB ANKRD17 SCP2 TWIST2 SNAP25 AFP DAZAP1 ZNF483 C8ORF58 GPBP1L1 ZNF454 PAX5 RFX7 |

| HF- vs. LF-EpiTS | miR-191 | 4 | NEURL4 TAF5 CREBB CASTOR2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinez, C.A.; Roca, J.; Alvarez-Rodriguez, M.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H. miRNA-Profiling in Ejaculated and Epididymal Pig Spermatozoa and Their Relation to Fertility after Artificial Insemination. Biology 2022, 11, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11020236

Martinez CA, Roca J, Alvarez-Rodriguez M, Rodriguez-Martinez H. miRNA-Profiling in Ejaculated and Epididymal Pig Spermatozoa and Their Relation to Fertility after Artificial Insemination. Biology. 2022; 11(2):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11020236

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez, Cristina A., Jordi Roca, Manuel Alvarez-Rodriguez, and Heriberto Rodriguez-Martinez. 2022. "miRNA-Profiling in Ejaculated and Epididymal Pig Spermatozoa and Their Relation to Fertility after Artificial Insemination" Biology 11, no. 2: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11020236

APA StyleMartinez, C. A., Roca, J., Alvarez-Rodriguez, M., & Rodriguez-Martinez, H. (2022). miRNA-Profiling in Ejaculated and Epididymal Pig Spermatozoa and Their Relation to Fertility after Artificial Insemination. Biology, 11(2), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11020236