In Vitro Osteogenic and Angiogenic Potential of 3D-Printed nHA/PCL Scaffolds Functionalized with a Photo-Crosslinked CSMA Hydrogel–Exosome Composite Coating

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation, Characterization, and Physicochemical Properties of Scaffolds

2.1.1. Preparation of 3D Printed 20% nHA/PCL Scaffolds

2.1.2. Characterization of nHA/PCL Scaffolds

2.1.3. Compression Performance of the Scaffold

2.1.4. Porosity of the Scaffold

2.2. Exosome Extraction and Identification

2.2.1. Cell Culture

2.2.2. Exosome Extraction

2.2.3. Exosome Identification

2.3. Characterization and Performance of CSMA Hydrogels

2.3.1. Preparation and SEM of Hydrogel

2.3.2. Hydrogel Injectability

2.3.3. Hydrogel Degradation

2.3.4. Hydrogel Porosity

2.4. Exosome Release in Hydrogels

2.5. Exosome Internalization

2.6. Preparation of Composite Scaffolds, Characterization and Their Hydrophilicity

2.6.1. Preparation of Composite Scaffolds

2.6.2. SEM

2.6.3. Compression Test

2.6.4. Hydrophilicity of Scaffolds

2.7. Hemolysis Test

2.8. Cell-Viability Assay and Cell Proliferation

2.9. Cell Scratch Assay

2.10. Tube Formation Assay

2.11. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Staining

2.12. Alizarin Red S (ARS) Staining

2.13. Immunofluorescence

2.14. qRT-PCR

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization and Properties of nHA/PCL Scaffold

3.2. Exosome Identification and Characterization

3.3. Characterization of Hydrogels and Release of Exosomes

3.4. Characterization and Properties of Composite Scaffolds

3.5. Hemolysis Test

3.6. Cell Proliferation, Viability, and Cytotoxicity

3.7. Cell Scratch Assay

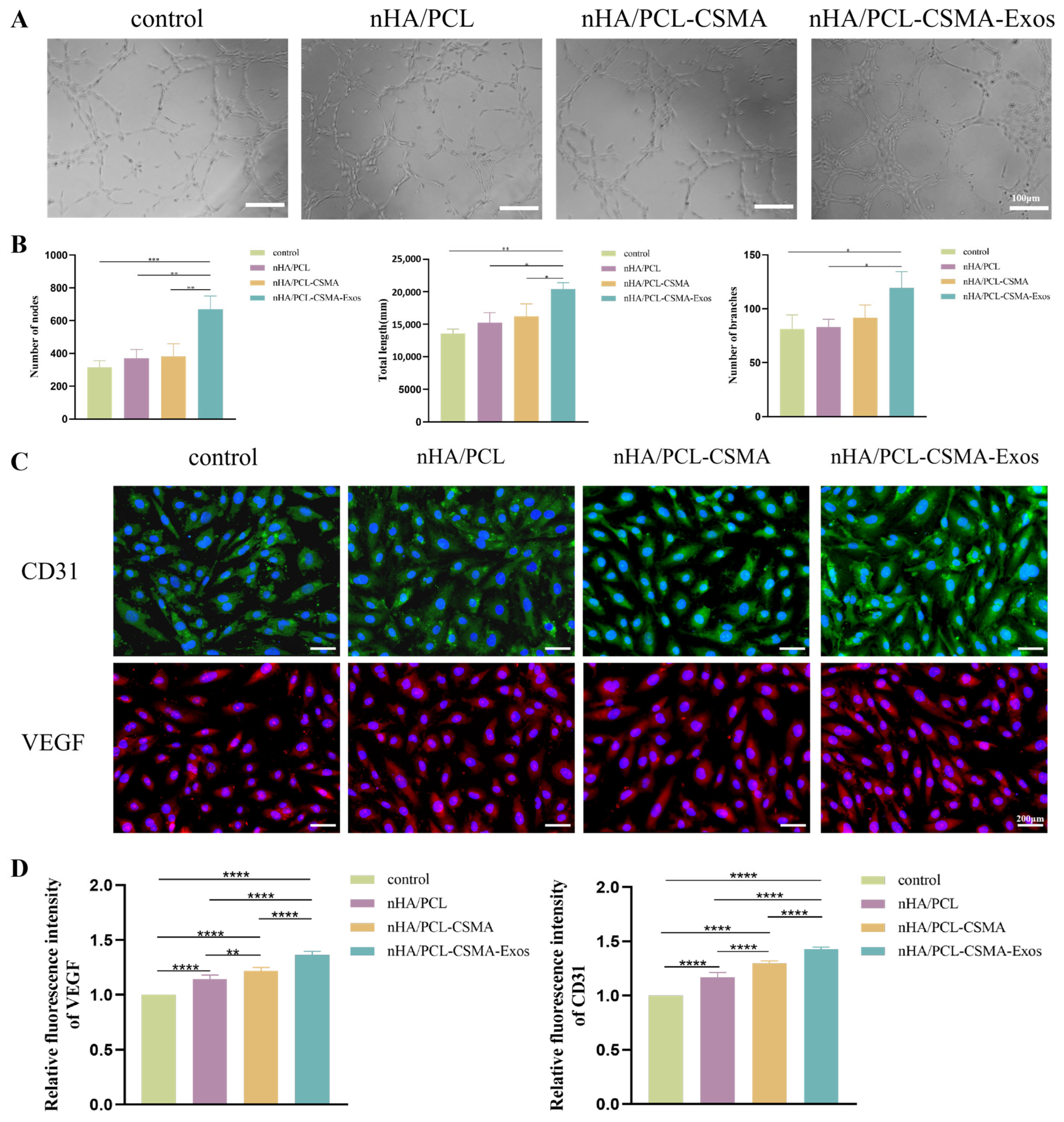

3.8. Tube Formation Assay

3.9. Immunofluorescence

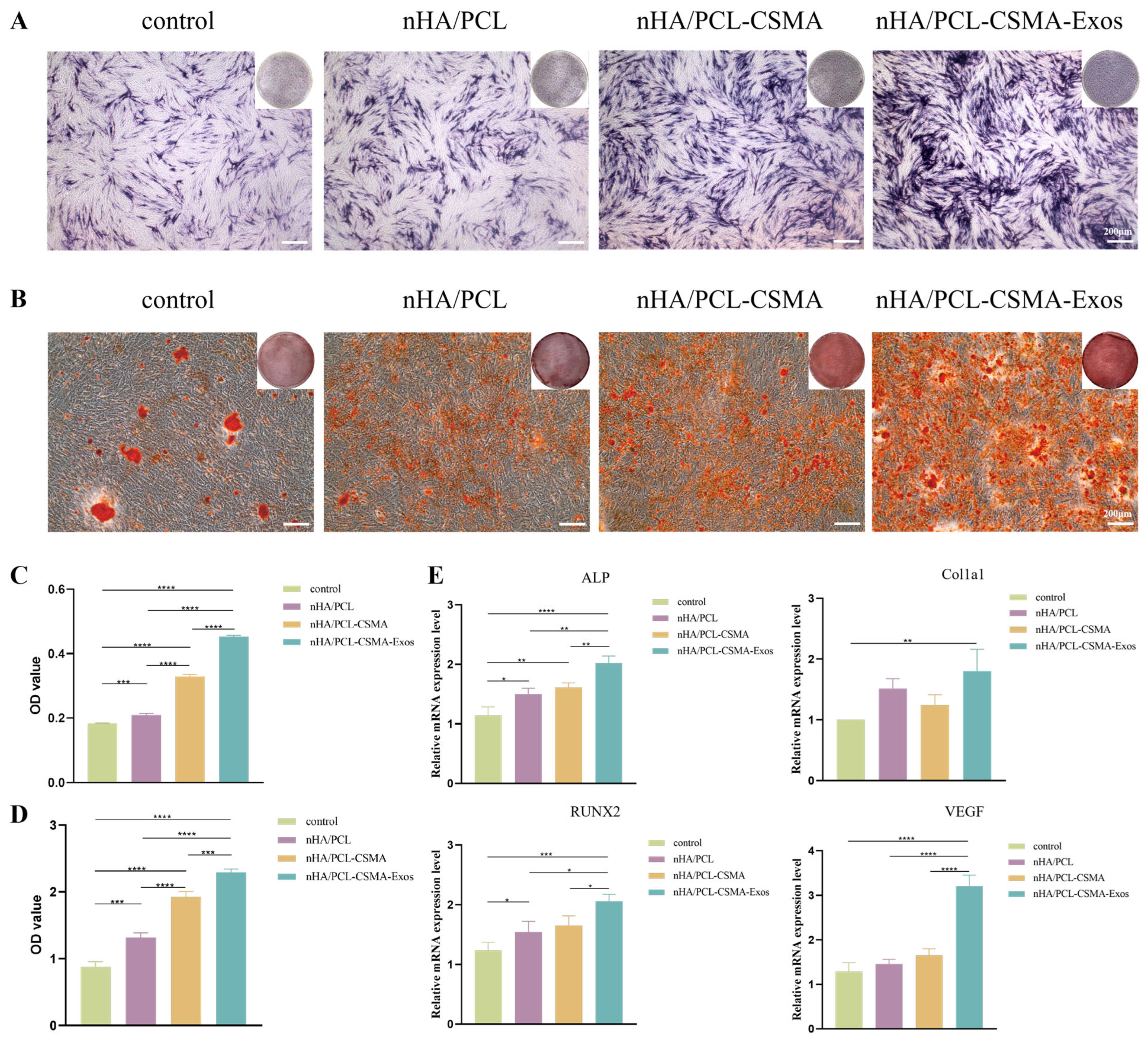

3.10. Alcian Blue and ARS Staining

3.11. qRT-PCR

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gillman, C.E.; Jayasuriya, A.C. FDA-approved bone grafts and bone graft substitute devices in bone regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 130, 112466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.H. Autologous bone graft: Is it still the gold standard? Injury 2021, 52, S18–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhorov, A.; Romansky, R.; Yanev, N.; Nikolov, V.; Slavkov, S. One-stage (primary) reconstructions of resection mandibular defects by means of autogene vascularised iliac and fibular transplant. Khirurgiia 2015, 81, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ciocca, L.; Marchetti, C.; Mazzoni, S.; Baldissara, P.; Gatto, M.R.; Cipriani, R.; Scotti, R.; Tarsitano, A. Accuracy of fibular sectioning and insertion into a rapid-prototyped bone plate, for mandibular reconstruction using CAD-CAM technology. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battafarano, G.; Rossi, M.; De Martino, V.; Marampon, F.; Borro, L.; Secinaro, A.; Del Fattore, A. Strategies for Bone Regeneration: From Graft to Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez de Grado, G.; Keller, L.; Idoux-Gillet, Y.; Wagner, Q.; Musset, A.M.; Benkirane-Jessel, N.; Bornert, F.; Offner, D. Bone substitutes: A review of their characteristics, clinical use, and perspectives for large bone defects management. J. Tissue Eng. 2018, 9, 2041731418776819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, V.M.; Kumar, L. 3D Printing as a Promising Tool in Personalized Medi-cine. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Z.U.; Khalid, M.Y.; Noroozi, R.; Hossain, M.; Shi, H.H.; Tariq, A.; Ra-makrishna, S.; Umer, R. Additive manufacturing of sustainable biomaterials for biomedical applications. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 18, 100812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y. Surface Modification of Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Polymer Composite for Bone Tissue Repair Applica-tions: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Zaffarin, A.S.; Ng, S.F.; Ng, M.H.; Hassan, H.; Alias, E. Nano-Hydroxyapatite as a Delivery System for Promoting Bone Regeneration In Vivo: A Systematic Review. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, S.E.; Henry, L.; McGennisken, E.; Onofrillo, C.; Bella, C.D.; Duchi, S.; O’Connell, C.D.; Pirogova, E. Characterization of Polycaprolactone Nanohy-droxyapatite Composites with Tunable Degradability Suitable for Indirect Printing. Polymers 2021, 13, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backes, E.H.; Harb, S.V.; Beatrice, C.A.G.; Shimomura, K.M.B.; Passador, F.R.; Costa, L.C.; Pessan, L.A. Polycaprolactone usage in additive manufac-turing strategies for tissue engineering applications: A review. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2022, 110, 1479–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Soares, I.P.; Anselmi, C.; Kitagawa, F.A.; Ribeiro, R.A.O.; Leite, M.L.; de Souza Costa, C.A.; Hebling, J. Nano-hydroxyapatite-incorporated polycaprolactone nanofibrous scaffold as a dentin tissue engineering-based strategy for vital pulp therapy. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 960–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, Z.; Irani, S.; Ardeshirylajimi, A.; Seyedjafari, E. Enhanced osteo-genic differentiation of stem cells by 3D printed PCL scaffolds coated with collagen and hydroxyapatite. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, P.K.; Fan, F.Y.; Lin, W.C.; Liao, P.B.; Huang, C.F.; Shen, Y.K.; Ruslin, M.; Lee, C.H. Bioactivity and Bone Cell Formation with Poly-ε-Caprolactone/Bioceramic 3D Porous Scaffolds. Polymers 2021, 13, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Caetano, G.; Vyas, C.; Blaker, J.J.; Diver, C.; Bártolo, P. Poly-mer-Ceramic Composite Scaffolds: The Effect of Hydroxyapatite and β-tri-Calcium Phosphate. Materials 2018, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezania, N.; Asadi-Eydivand, M.; Abolfathi, N.; Bonakdar, S.; Mehrjoo, M.; Solati-Hashjin, M. Three-dimensional printing of polycaprolactone/hydroxyapatite bone tissue engineering scaffolds mechanical properties and biological behavior. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2022, 33, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, J.; Liu, B.; Shao, C.; Shi, Y. Reciprocal regulation of mesen-chymal stem cells and immune responses. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 1515–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Yuan, Z.; Weng, J.; Pei, D.; Du, X.; He, C.; Lai, P. Challenges and advances in clinical applications of mesenchymal stromal cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Nam, G.H.; Hong, Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, D.H.; Yang, Y.; Kim, I.S. Comparison of exosomes and ferritin protein nanocages for the delivery of membrane protein therapeutics. J. Control. Release 2018, 279, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, M.; Bijari, S.; Khazaei, A.H.; Shojaei-Ghahrizjani, F.; Rezakhani, L. The role of milk-derived exosomes in the treatment of diseases. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1009338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, A.; Rahman, H.S.; Markov, A.; Endjun, J.J.; Zekiy, A.O.; Char-trand, M.S.; Beheshtkhoo, N.; Kouhbanani, M.A.J.; Marofi, F.; Nikoo, M.; et al. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell-derived exosomes in regenerative medi-cine and cancer; overview of development, challenges, and opportunities. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wong, K.L.; Ren, X.; Teo, K.Y.W.; Afizah, H.; Choo, A.B.H.; Lai, R.C.; Lim, S.K.; Hui, J.H.P.; Toh, W.S. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes Promote Functional Osteochondral Repair in a Clinically Relevant Porcine Model. Am. J. Sports Med. 2022, 50, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukomska, B.; Stanaszek, L.; Zuba-Surma, E.; Legosz, P.; Sarzynska, S.; Drela, K. Challenges and Controversies in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 9628536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riau, A.K.; Ong, H.S.; Yam, G.H.F.; Mehta, J.S. Sustained Delivery System for Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annabi, N.; Tamayol, A.; Uquillas, J.A.; Akbari, M.; Bertassoni, L.E.; Cha, C.; Camci-Unal, G.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Peppas, N.A.; Khademhosseini, A. 25th an-niversary article: Rational design and applications of hydrogels in regenera-tive medicine. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 85–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Guan, Q.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y.; Yin, Y.; Han, X. Hydrogels for Exosome Delivery in Biomedical Applications. Gels 2022, 8, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, M.; Hu, Y.; Chen, R.; Hao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Exo-some-Hydrogel System in Bone Tissue Engineering: A Promising Therapeu-tic Strategy. Macromol. Biosci. 2023, 23, e2200496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.; Layrolle, P.; Mooney, D.J. Biomaterials functionalized with MSC secreted extracellular vesicles and soluble factors for tissue regenera-tion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1909125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, N.H.N.; Truong, Q.T.; Le, P.K.; Ha, A.C. Recent developments in chi-tosan hydrogels carrying natural bioactive compounds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 294, 119726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Wang, J.; Hou, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Fu, J.; Lu, L.; Gao, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, F.; et al. Review: Application of chitosan and its derivatives in medical materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 240, 124398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, B.; Aghazadeh, M.; Davaran, S.; Roshangar, L. Exosome-loaded hy-drogels: A new cell-free therapeutic approach for skin regeneration. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2022, 171, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Du, C.; Yang, X.; Yao, Y.; Qin, D.; Meng, F.; Yang, S.; Tan, Y.; Chen, X.; Jiang, W.; et al. Instantaneous Self-Healing Chitosan Hydrogels with En-hanced Drug Leakage Resistance for Infected Stretchable Wounds Healing. Small 2025, 121, 2409641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osi, A.R.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Fu, J.; Müller-Buschbaum, P.; Zhong, Q. Three-Dimensional-Printable Thermo/Photo-Cross-Linked Methacrylated Chitosan-Gelatin Hydrogel Composites for Tissue Engineer-ing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 22902–22913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yan, B.; Shi, A.; Xu, J.; Guan, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, P.; Mao, Y. Mechanically enhanced composite hydrogel scaffold for in situ bone repairs. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 134, 112700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Shu, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhuo, C.; Zhuo, N. Charac-terization and Biocompatibility Assessment of 3D-Printed HA/PCL Porous Bionic Bone Scaffold: In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2025, 25, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistani, S.; Asgharzade, S.; Arab, S.; Bahraminasab, M.; Soltani-Fard, E. Fabrication and evaluation of a host-guest polylactic acid/gelatin-hydroxyapatite-blueberry scaffold for bone regeneration. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Xu, J.; Meng, L.a.; Su, Y.; Fang, H.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Jiang, D.; Nie, Y.; Song, K. 3D bioprinting of dECM/Gel/QCS/nHAp hybrid scaffolds laden with mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes to improve angiogene-sis and osteogenesis. Biofabrication 2023, 15, 024103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Xu, C.; Meng, L.; Dong, X.; Qi, M.; Jiang, D. Exo-some-functionalized magnesium-organic framework-based scaffolds with osteogenic, angiogenic and anti-inflammatory properties for accelerated bone regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 18, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyuksungur, S.; Hasirci, V.; Hasirci, N. 3D printed hybrid bone constructs of PCL and dental pulp stem cells loaded GelMA. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2021, 109, 2425–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.; Liu, C.; Xie, D.; Mao, S.; Ji, Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Fan, L.; Sun, Y. Exosome-loaded extracellular matrix-mimic hydrogel with an-ti-inflammatory property Facilitates/promotes growth plate injury repair. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 10, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Jiang, L. Contact angle measurement of natural materials. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces 2018, 161, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Kang, M.; Qu, Y.; Hou, T.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, X. Incorporating Hy-drogel (with Low Polymeric Content) into 3D-Printed PLGA Scaffolds for Local and Sustained Release of BMP2 in Repairing Large Segmental Bone Defects. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 14, 2403613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almela, T.; Brook, I.M.; Khoshroo, K.; Rasoulianboroujeni, M.; Fahimipour, F.; Tahriri, M.; Dashtimoghadam, E.; El-Awa, A.; Tayebi, L.; Moharamzadeh, K. Simulation of cortico-cancellous bone structure by 3D printing of bilayer calcium phosphate-based scaffolds. Bioprinting 2017, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.-Y.; Lee, W.-K.; Hsu, J.-T.; Shih, J.-Y.; Ma, T.-L.; Vo, T.T.T.; Lee, C.-W.; Cheng, M.-T.; Lee, I.-T. Polycaprolactone in Bone Tissue Engineering: A Comprehensive Review of Innovations in Scaffold Fabrication and Surface Modifications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Rodríguez, J.; Renou, S.J.; Guglielmotti, M.B.; Olmedo, D.G. Tis-sue response to porous high density polyethylene as a three-dimensional scaffold for bone tissue engineering: An experimental study. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2019, 30, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, X.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Liu, C.; Yang, X. Biomimetic porous scaf-folds for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2014, 80, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pushpalatha, C.; Gayathri, V.S.; Sowmya, S.V.; Augustine, D.; Alamoudi, A.; Zidane, B.; Hassan Mohammad Albar, N.; Bhandi, S. Nanohydroxyapatite in dentistry: A comprehensive review. Saudi Dent. J. 2023, 35, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Meng, X.; Pan, Z.; Li, Y.; Qian, H.; Zhu, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. Advancements in nanohydroxyapatite: Synthesis, biomedical applications and composite developments. Regen. Biomater. 2025, 12, rbae129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abere, D.V.; Ojo, S.; Oyatogun, G.M.; Paredes-Epinosa, M.B.; Niluxsshun, M.C.D.; Hakami, A. Mechanical and morphological characterization of nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) for bone regeneration: A mini review. Biomed. Eng. Adv. 2022, 4, 100056. [Google Scholar]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andri-antsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, N.; Yan, T.; Shi, Y.N.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C.J.; Xie, X.J.; Liao, D.F.; Qin, L. The crosstalk: Exosomes and lipid metabolism. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2020, 18, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, G.; Ramos, E.K.; Lee, K.E.; Bedoyan, S.; Huang, S.; Samaeekia, R.; Athman, J.J.; Harding, C.V.; Lötvall, J.; Harris, L.; et al. A rapid, automated surface protein profiling of single circulating exosomes in human blood. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardpour, S.; Ghanian, M.H.; Sadeghi-Abandansari, H.; Mardpour, S.; Naz-ari, A.; Shekari, F.; Baharvand, H. Hydrogel-Mediated Sustained Systemic Delivery of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Im-proves Hepatic Regeneration in Chronic Liver Failure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 37421–37433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.H.; Pi, J.K.; Zou, C.Y.; Jiang, Y.L.; Li, Q.J.; Zhang, X.Z.; Xing, F.; Xie, R.; Han, C.; Xie, H.Q. Hydrogel-exosome system in tissue engineering: A promising therapeutic strategy. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 38, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, K.R.; Chatterjee, N.; Misra, S.K.; Verma, V. A bacterial cellu-lose-polydopamine based injectable hydrogel for enhanced hemostasis in acute wounds. Biomater. Sci. 2025, 13, 3307–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, E.A.; Finley, S.D.; Popel, A.S.; Mac Gabhann, F. A systems biology view of blood vessel growth and remodelling. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18, 1491–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, F.M.; Gray, N.S. Kinase inhibitors: The road ahead. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissaux, C.; Ruffenach, L.; Bruant-Rodier, C.; George, D.; Bodin, F.; Rémond, Y. Cleft Alveolar Bone Graft Materials: Literature Review. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2022, 59, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Rochlin, D.H.; Parsaei, Y.; Shetye, P.R.; Witek, L.; Leucht, P.; Rabbani, P.S.; Flores, R.L. Bone Tissue Engineering Strategies for Alveolar Cleft: Review of Preclinical Results and Guidelines for Future Studies. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2023, 60, 1450–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | Atomic Number | Normalized Quality (%) | Atom (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 6 | 54.30 | 64.93 |

| O | 8 | 33.99 | 30.51 |

| Ca | 20 | 8.32 | 2.98 |

| P | 15 | 3.40 | 1.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Dong, W.; Hu, C.; Yu, L.; Yan, D.; Fu, W.; Huang, Y.; Ma, J. In Vitro Osteogenic and Angiogenic Potential of 3D-Printed nHA/PCL Scaffolds Functionalized with a Photo-Crosslinked CSMA Hydrogel–Exosome Composite Coating. Coatings 2026, 16, 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020201

Liu Y, Dong W, Hu C, Yu L, Yan D, Fu W, Huang Y, Ma J. In Vitro Osteogenic and Angiogenic Potential of 3D-Printed nHA/PCL Scaffolds Functionalized with a Photo-Crosslinked CSMA Hydrogel–Exosome Composite Coating. Coatings. 2026; 16(2):201. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020201

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yujie, Wen Dong, Chen Hu, Lili Yu, Di Yan, Wenjing Fu, Yongqing Huang, and Jian Ma. 2026. "In Vitro Osteogenic and Angiogenic Potential of 3D-Printed nHA/PCL Scaffolds Functionalized with a Photo-Crosslinked CSMA Hydrogel–Exosome Composite Coating" Coatings 16, no. 2: 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020201

APA StyleLiu, Y., Dong, W., Hu, C., Yu, L., Yan, D., Fu, W., Huang, Y., & Ma, J. (2026). In Vitro Osteogenic and Angiogenic Potential of 3D-Printed nHA/PCL Scaffolds Functionalized with a Photo-Crosslinked CSMA Hydrogel–Exosome Composite Coating. Coatings, 16(2), 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16020201