Application of Electrospun Nanofiber Membranes in Outdoor Sportswear: From Preparation Technologies to Multifunctional Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preparation Technologies, Structural Regulation, and Performance Relationships of Nanofiber Membranes

2.1. Electrospinning Technology

2.2. Factors Influencing the Preparation of Nanofiber Membranes via Electrospinning Technology

2.2.1. Solution Properties

2.2.2. Process Parameters

2.2.3. Environmental Conditions

2.3. Overview and Comparison of Other Fabrication Techniques

| Fabrication Techniques | Main Advantages | Main Limitations | Applicable Materials | Commercial Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospinning [32] | Simple equipment, uniform fibers, capable of producing complex structures | Requires high-voltage electric field, limited production capacity | Various polymer solutions/melts | Mainstream approach in laboratory research and high-end specialty products. Still faces efficiency and cost challenges in the textile and apparel sector [33]. |

| Air-jet spinning [34] | No electric field required, high yield | Fiber diameter distribution wide | High viscosity solution | Possesses industrialization potential, suitable for fields requiring large-scale production with less stringent uniformity demands. More appropriate for use as a foundational functional layer in apparel [34]. |

| Centrifugal spinning [35] | High safety, large output | Complex equipment, disordered fibers | Polymer solution/melt | Suitable for large-scale production of coarser nanofiber/microfiber nonwoven fabrics; less competitive in the high-end membrane segment of outdoor apparel [36]. |

| Self-assembly [37] | Precise diameter, ultrafine fibers | Time-consuming process, low yield | Amphiphilic molecules, block copolymers | Suitable only for fundamental research and high-value-added micro-devices, not meeting the conditions for large-scale commercialization in outdoor apparel materials [37]. |

| Template synthesis [38] | Size controllable, single fiber | High template cost, complex process | Various polymers and inorganic materials | Primarily serves academic research, standard sample preparation, or fields with special performance requirements. Due to cost and production limitations, it is difficult to apply to commercial clothing production [39]. |

| Matrix Spinning [40] | Mild conditions, suitable for sensitive materials. | Low yield; matrix removal increases steps and costs | Biopolymers, hydrogels | Potential for applications in biomedical and other fields; for large-scale production of conventional outdoor clothing, it remains at the forefront of exploration, with technical and economic feasibility not yet mature [40]. |

| Conventional Coatings | Mature process, low cost, high output, good waterproofness | Poor breathability, limited functionality, environmental concerns, heavy add-on | Polymer dispersions/solutions (PU, acrylic, PTFE) | Dominant in current mass market for basic waterproof apparel; faces challenge in high-end breathable and smart segments. |

| Fabrication Techniques | Fiber Diameter Range | Production Efficiency | Relative Cost | Scalability | Fiber Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospinning [41] | 50 nm–5 μm | Moderate | Moderately high | Moderate | Uniform diameter, strong structural controllability |

| Air-jet spinning [42] | 100 nm–10 μm | High | Low to moderate | High | Wide size distribution |

| Centrifugal spinning [43] | 500 nm–20 μm | High | Low | High | Fibers are typically disordered |

| Self-assembly [44] | 1–50 nm | Extremely low | High | Extremely low | Precise diameter, molecular-level control |

| Template synthesis [45] | 20–500 nm | Low | High | Low | Highly controllable size and morphology |

| Matrix spinning [46] | 10–500 nm | Low | Moderate | Low to medium | Wide size distribution |

2.4. Construction Strategies for Multi-Level Structured Nanofiber Membranes

2.4.1. Precise Encapsulation of Multi-Axial Fiber Core–Shell Structures

2.4.2. Porous/Beaded Fibers Increase Specific Surface Area and Roughness

2.4.3. Special Wettability Surfaces Inspired by Lotus Leaves, Spider Silk, Etc.

2.4.4. Multifunctional Integrated Structures

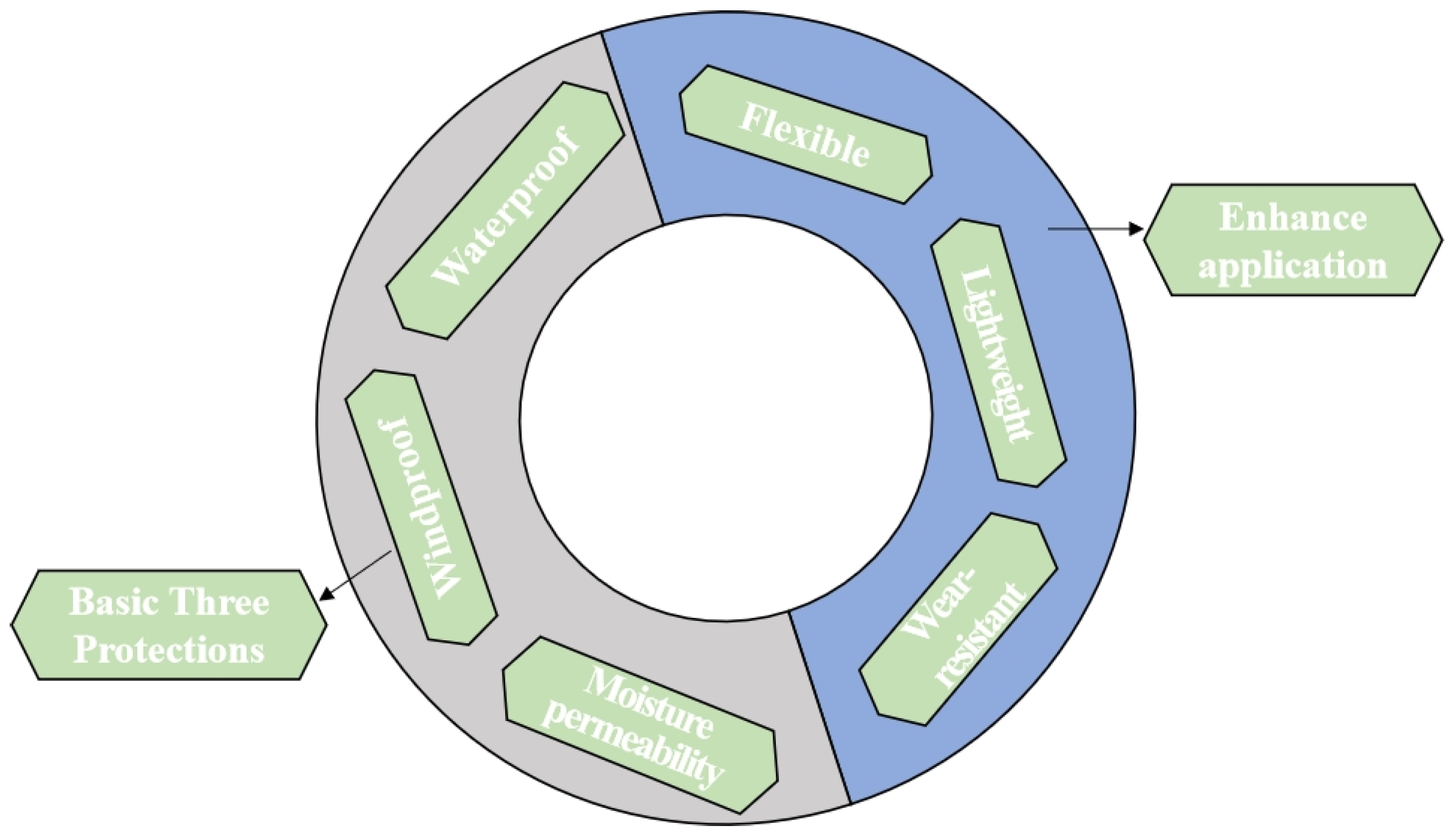

3. Research Progress on Multifunctional Integration of Nanofiber Membranes for Outdoor Clothing

3.1. High-Efficiency Waterproof and Moisture-Permeable

3.1.1. Mechanism Analysis

3.1.2. Implementation Strategies

3.1.3. Performance Comparison and Trade-Off Analysis

3.2. Thermal Comfort Management

3.2.1. Passive Thermal Management

3.2.2. Active Thermal Management

3.3. Enhanced Durability and Protection

3.3.1. Mechanical Performance Enhancement and Key Parameter Analysis

3.3.2. Anti-UV Functionality

3.3.3. Antibacterial and Antimicrobial Functions

3.4. Intelligent Response and Sensing

3.4.1. Stimulus-Responsive Membranes

3.4.2. Integrated Sensing

3.5. Sustainability Exploration

3.5.1. Source Reduction and Process Optimization

3.5.2. Recycling and Reuse of Membrane Materials

4. Application of Nanofiber Membranes in Outdoor Sportswear

4.1. Application of Nanofiber Membranes in Extreme Outdoor Sportswear

4.1.1. Design Strategies for Addressing the Conflict Between Extreme Protection and Moisture Permeability

4.1.2. Enhanced Thermal Management Capability in Extreme Environments

4.2. Application of Nanofiber Membranes in Long-Distance Trail Sports Apparel

4.2.1. Achieving Ultimate Moisture Permeability and Dynamic Comfort Management

4.2.2. Lightweight Design and Adaptive Thermal Management

4.3. Application of Nanofiber Membranes in Urban Outdoor Sportswear

4.3.1. Integrated Fusion of Protection, Moisture Permeability, and Esthetics

4.3.2. Smart Responsiveness and Multifunctional Integration for Diverse Scenarios

4.3.3. Unification of Esthetic Expression and Sustainability

4.4. Industry Standards and Standardization Process

5. Challenges in Applying Nanofiber Membranes to Outdoor Sportswear

5.1. In-Depth Analysis of Scale-Up Production, Cost, and Performance Trade-Offs

5.2. High Production Costs

5.3. Challenges in Product Uniformity and Quality Control

6. Summary and Outlook

6.1. Summary

6.2. Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vande-Vliet, È.; Inglés, E.; Mateu, P.; Montull, L. Risk-Taking: Liquid Modernity and Extreme Outdoor Practitioners. World Leis. J. 2023, 66, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Bian, X.; Wang, Y.; Lam, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, S.; Qi, P.; Qu, Z.; Xin, J.H. Janus outdoor protective clothing with unidirectional moisture transfer, antibacterial, and mosquito repellent properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 490, 151826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Liu, F. Review of Waterproof Breathable Membranes: Preparation, Performance and Applications in the Textile Field. Materials 2023, 16, 5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, C.; Laustsen, A.H. Recent Advances in Next Generation Snakebite Antivenoms. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Qu, C.; Li, X.; Ding, C.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Sustainable Bi-directional thermoregulation fabric for clothing microclimate. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Mishra, P.; Verma, K.; Mondal, A.; Chaudhary, R.G.; Abolhasani, M.M.; Loganathan, S. Electrospinning production of nanofibrous membranes. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 767–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suja, P.S.; Reshmi, C.R.; Sagitha, P.; Sujith, A. Electrospun Nanofibrous Membranes for Water Purification. Polym. Rev. 2017, 57, 467–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Chen, C.; Tian, M. The intellectual base, knowledge evolution, and frontiers of research on smart clothing: A visual analysis of research trajectory. Text. Res. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knížek, R.; Tunák, M.; Tunáková, V.; Honzíková, P. Effect of membrane morphology on the thermo-physiological comfort of outdoor clothing. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2024, 19, 15589250241265334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Liu, M. Personalized Smart Clothing Design Based on Multimodal Visual Data Detection. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 4440652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabe, S. Electrospun Nanofiber Membranes and Their Applications in Water and Wastewater Treatment. In Nanotechnology for Water Treatment and Purification; Lecture Notes in Nanoscale Science and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 111–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, S.; Guo, F. Janus Nanofibrous Membranes for Desalination by Air Gap Membrane Distillation. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 1, 3443–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, S.X.; Kong, W.; Chen, C.; Hitz, E.; Jia, C.; Dai, J.; Zhang, X.; Briber, R.; Siwy, Z.; et al. A nanofluidic ion regulation membrane with aligned cellulose nanofibers. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, M.E.; Talukder, M.R.; Pervez, M.N.; Song, H.; Naddeo, V. Bead-Containing Superhydrophobic Nanofiber Membrane for Membrane Distillation. Membranes 2024, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Low, Z.-X.; Hegab, H.M.; Xie, Z.; Ou, R.; Yang, G.; Simon, G.P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Enhancement of desalination performance of thin-film nanocomposite membrane by cellulose nanofibers. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 592, 117363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zeng, L.; Qiao, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Ding, J. Fabrication of Electrospun Polymer Nanofibers with Diverse Morphologies. Molecules 2019, 24, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcinkaya, B.; Buzgo, M. A Guide for Industrial Needleless Electrospinning of Synthetic and Hybrid Nanofibers. Polymers 2025, 17, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, H.; Li, X.; Deng, L.; Li, P.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Hsiao, B.S. Silver Nanoparticle-Enabled Photothermal Nanofibrous Membrane for Light-Driven Membrane Distillation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 3269–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robiul Islam, M.; Faruk, O.; Rana, S.M.S.; Pradhan, G.B.; Kim, H.; Reza, M.S.; Bhatta, T.; Park, J.Y. Poly-DADMAC Functionalized Polyethylene Oxide Composite Nanofibrous Mat as Highly Positive Material for Triboelectric Nanogenerators and Self-Powered Pressure Sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2403899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; He, P.; Si, Y.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Multifunctional, Waterproof, and Breathable Nanofibrous Textiles Based on Fluorine-Free, All-Water-Based Coatings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 15911–15918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misaka, M.; Teshima, H.; Hirokawa, S.; Li, Q.-Y.; Takahashi, K. Nano-Captured Water Affects the Wettability of Cellulose Nanofiber Films. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 46, 103923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, G.A.; Aguado, R.J.; Galván, M.V.; Zanuttini, M.Á.; Delgado-Aguilar, M.; Tarrés, Q. Impact of cellulose nanofibers on cellulose acetate membrane performance. Cellulose 2024, 31, 2221–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Kang, W.; Deng, N.; Yan, J.; Ju, J.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, B. Preparation and characterization of tree-like cellulose nanofiber membranes via the electrospinning method. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 183, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Xiao, X.; Au, C.; Mathur, S.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Kipper, M.J.; Tang, J.; et al. Electrospinning nanofibers and nanomembranes for oil/water separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 21659–21684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, D.; Bai, T.; Cheng, W.; Han, G.; Ni, X.; Shi, Q.S. Electrospun PVA Nanofibrous Membranes Reinforced with Silver Nanoparticles Impregnated Cellulosic Fibers: Morphology and Antibacterial Property. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2021, 37, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yixuan, T.; Zhengwei, C.; Xiaoxia, S.; Chuanmei, C.; Xinfei, Y.; Mingdi, L.; Jia, X. Electrospun Nanofiber-Based Membranes for Water Treatment. Polymers 2022, 14, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnappan, B.A.; Krishnaswamy, M.; Xu, H.; Hoque, M.E. Electrospinning of Biomedical Nanofibers/Nanomembranes: Effects of Process Parameters. Polymers 2022, 14, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, T.; Meng, C.; Zeng, G. Morphological, Thermal, Mechanical, and Optical Properties of Hybrid Nanocellulose Film Containing Cellulose Nanofiber and Cellulose Nanocrystals. Fibers Polym. 2021, 22, 2187–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, M.; Mahar, F.K.; Wei, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wei, K. Fabrication of fibrous nanofiber membranes for passive radiation cooling. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 16080–16090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, J.; Gong, G.; Hu, Y. Incorporating TiO2 nanocages into electrospun nanofibrous membrane for efficient and anti-fouling membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 698, 122614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, B.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, E.; Li, J.; Ren, Y. High-performance polyimide nanofiber membranes prepared by electrospinning. High Perform. Polym. 2018, 31, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Chang, Z.; E, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yao, X.; Wang, M.; Ju, Y.; Wang, K.; Jiang, J.; Li, P.; et al. Electrospinning and electrospun polysaccharide-based nanofiber membranes: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aijaz, M.O.; Othman, M.H.D.; Karim, M.R.; Ullah Khan, A.; Najib, A.; Assaifan, A.K.; Alharbi, H.F.; Alnaser, I.A.; Puteh, M.H. Electrospun bio-polymeric nanofibrous membrane for membrane distillation desalination application. Desalination 2024, 586, 117825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, G.; Wang, C.; Li, C.; Xiao, C. Super Fine Para-Aramid Nanofiber and Membrane Fabricated by Airflow-Assisted Coaxial Spinning. Polymer 2024, 311, 127566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xu, J.; Ye, H.; Zhao, M.; Li, W.; Yang, B.; Li, X. Centrifugal Spinning of PVDF Micro/Nanofibrous Membrane for Oil–Water Separation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 25665–25674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Yagi, S.; Meng, J.; Dong, Y.; Qian, C.; Zhao, D.; Kumar, A.; Xu, T.; Lucchetti, A.; Xu, H. High-efficiency production of core-sheath nanofiber membrane via co-axial electro-centrifugal spinning for controlled drug release. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 654, 120571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Ko, Y.T.; Ji, M.; Cho, J.S.; Wang, D.H.; Lee, Y.-I. Facile self-assembly-based fabrication of a polyvinylidene fluoride nanofiber membrane with immobilized titanium dioxide nanoparticles for dye wastewater treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Cao, W.; Lu, T.; Xiong, R.; Huang, C. Multifunctional nanofibrous membrane fabrication by a sacrifice template strategy for efficient emulsion oily wastewater separation and water purification. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, M.; Li, H. Electrochemical copolymerization of pyrrole and thiophene nanofibrils using template-synthesis method. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 86, 2403–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, I.; Palchikova, E.; Vinogradov, M.; Golubev, Y.; Legkov, S.; Gromovykh, P.; Makarov, G.; Arkharova, N.; Karimov, D.; Gainutdinov, R. Characterization of Structure and Morphology of Cellulose Lyocell Microfibers Extracted from PAN Matrix. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chen, R.; Lu, P.; Zheng, Z.; Gu, G.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X. Electrospun PAN-HNTs composite nanofiber membranes for efficient electrostatic capture of particulate matters. Nanotechnology 2022, 33, 265702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, T.; Wang, X. Use of airflow to improve the nanofibrous structure and quality of nanofibers from needleless electrospinning. J. Ind. Text. 2014, 45, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Ye, H.; Zhao, M.; Li, W.; Yang, B.; Li, X. A biodegradable bi-layer nano fibrous membrane fabricated by centrifugal spinning for active food packaging. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 142, e56342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Liang, Q.; Gao, Q. Preparation of hydroxypropyl starch/polyvinyl alcohol composite nanofibers films and improvement of hydrophobic properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 223, 1297–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, H. Preparation and characterization of pyrrole/aniline copolymer nanofibrils using the template-synthesis method. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 81, 3002–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouladivanda, M.; Karimi-Sabet, J.; Abbasi, F.; Moosavian, M.A. Step-by-step improvement of mixed-matrix nanofiber membrane with functionalized graphene oxide for desalination via air-gap membrane distillation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 256, 117809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.R.; Sharma, S.K.; Lindström, T.; Hsiao, B.S. Nanocellulose-Enabled Membranes for Water Purification: Perspectives. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2020, 4, 1900114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turky, A.O.; Barhoum, A.; MohamedRashad, M.; Bechlany, M. Enhanced the structure and optical properties for ZnO/PVP nanofibers fabricated via electrospinning technique. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 17526–17532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ji, C.; Li, J.; Pan, X. Facile preparation and properties of superhydrophobic nanocellulose membrane. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 103964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, R.; Scaffaro, R.; Maio, A.; Gulino, E.F.; Lo Re, G.; Jonoobi, M. Processing-structure-property relationships of electrospun PLA-PEO membranes reinforced with enzymatic cellulose nanofibers. Polym. Test. 2020, 81, 106182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, T.; Yan, Z.; Ji, D.; Li, J.; Pan, H. Preparation and evaluation of dual drug-loaded nanofiber membranes based on coaxial electrostatic spinning technology. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 629, 122410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Ren, Z.; Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; Pan, J.; Huang, J.; Zhu, T.; Cheng, S.; Lai, Y. Recent Progress of Electrospun Nanofiber-Based Composite Materials for Monitoring Physical, Physiological, and Body Fluid Signals. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Cheng, X.; Luo, R.; Gu, R. Regulation of the Properties of Nafion and PVDF Nanofibrous Membranes by Designing Fiber Structures. J. Polym. Sci. 2025, 63, 1774–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Lei, T.; Li, W.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Q. Nanocellulose films with combined cellulose nanofibers and nanocrystals: Tailored thermal, optical and mechanical properties. Cellulose 2017, 25, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-D.; Fan, J.-W.; Liu, H.-Y.; Su, B.; Ha, X.-Y.; Guo, Z.-Y. Carbon Nanofiber-Based Electrical Heating Films Incorporating Carbon Powder. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 143, 110911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Guo, F.; Wen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Cheng, S. Strong and anti-swelling nanofibrous hydrogel composites inspired by biological tissue for amphibious motion sensors. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 5600–5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Tominaga, Y.; Hotta, Y.; Shibuya, H.; Sugie, M.; Saruyama, T. Cellulose nanofiber/nanodiamond composite films: Thermal conductivity enhancement achieved by a tuned nanostructure. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 972–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Lin, F.; Zhao, W.; Lombardi, J.P.; Almihdhar, M.; Liu, K.; Yan, S.; Kim, J.; Luo, J.; Hsiao, B.S.; et al. Nanoparticle–Nanofibrous Membranes as Scaffolds for Flexible Sweat Sensors. ACS Sens. 2016, 1, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-González, M.; Felix, M.; Romero, A. Rice Bran Valorization through the Fabrication of Nanofibrous Membranes by Electrospinning. Processes 2024, 12, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, S.; Johnson, B.; Smith, A.L. Optimizing electrospinning parameters for piezoelectric PVDF nanofiber membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 563, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskovec, J.; Čapková, P.; Ryšánek, P.; Gardenö, D.; Friess, K.; Jarolímková, J.; Greguš, V.; Kaule, P.; Dušková, T.; Škvorová, M.; et al. A hydrogen adsorbing PUR/Pd nanocomposite nanofibrous membrane prepared by electrospinning technology. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 25202–25210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, S.; Siponkoski, T.; Sarlin, E.; Mettänen, M.; Vuoriluoto, M.; Pammo, A.; Juuti, J.; Rojas, O.J.; Franssila, S.; Tuukkanen, S. Cellulose Nanofibril Film as a Piezoelectric Sensor Material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 15607–15614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, G.; Ma, H.; Hsiao, B.S. Interpenetrating Nanofibrous Composite Membranes for Removal and Reutilization of P (V) Ions from Wastewater. Membranes 2025, 15, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Gu, J.; Liu, X.; Ren, Y.; Mi, X.; Zhan, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Ji, X.; Yue, Z.; et al. A Robust Core-Shell Nanofabric with Personal Protection, Health Monitoring and Physical Comfort for Smart Sportswear. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2411131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Cheng, Y.; Mo, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, H.; Hu, B.; Zhou, J. Electrospun Polytetrafluoroethylene Nanofibrous Membrane for High-Performance Self-Powered Sensors. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, L.; Liao, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, W.; Ko, F.; Zhao, J.; Qi, H.; Zhou, W. Electrospun Multifunctional Radiation Shielding Nanofibrous Membrane for Daily Human Protection. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2300760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Liu, J.; Li, D.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, R.; Ren, W.; Xie, S.; Cui, Z.; Wang, N. Electrospinning Janus Nanofibrous Membrane for Unidirectional Liquid Penetration and Its Applications. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2021, 37, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahi, A.; Shao, J.; Mohseni, M.; Ko, F.K. Membranes based on electrospun lignin-zeolite composite nanofibers. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 187, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, H.; He, J. Preparation and properties of composite phase-change nanofiber membrane by improved bubble electrospinning. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 055011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Zhao, P.; Xie, J.; Dong, S.; Liu, J.; Rao, C.; Fu, J. Electrospinning of Nanofibrous Membrane and Its Applications in Air Filtration: A Review. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, X.; Kang, W.; Cheng, B. Designing of electrospun unidirectional water transport nanofiber membranes: Mechanisms, structures, and applications. Polymer 2025, 324, 128221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, J.; Lv, J.; Chen, J.; Gao, D.; Zhang, X.; Lee, P.S. Mechanically interlocked stretchable nanofibers for multifunctional wearable triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, M.D.; Popa, M.L.; Neacșu, I.A.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Ginghină, O. Antimicrobial Clothing Based on Electrospun Fibers with ZnO Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, S.; Yousefzadeh, M.; Mousazadegan, F. Investigation of thermal comfort in nanofibrous three-layer fabric for cold weather protective clothing. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2019, 59, 2032–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Kuo, C.C.; Chen, B.Y.; Chiu, P.C.; Tsai, P.C. Multifunctional polyacrylonitrile-ZnO/Ag electrospun nanofiber membranes with various ZnO morphologies for photocatalytic, UV-shielding, and antibacterial applications. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2014, 53, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, T.; Kang, W.; Lu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y. Heat-localizing photothermal nanofiber membrane for enhanced photothermal membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 734, 124381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, V.; Kaleekkal, N.J.; Vigneswaran, S. Coaxial Electrospun Nanofibrous Membranes for Enhanced Water Recovery by Direct Contact Membrane Distillation. Polymers 2022, 14, 5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Q.; LiJuan, Y.; YaNan, H.; ShaoLong, Z.; DongLi, Z.; Ke, B.; YongXin, Z.; Yu, Z.; ZhiMin, D. Flexible and Stretchable Capacitive Sensors with Different Microstructures. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2008267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Rocca, F.; Badia-Valiente, J.D.; Jiménez-Robles, R.; Martínez-Soria, V.; Izquierdo, M. PVDF Nanofiber Membranes for Dissolved Methane Recovery from Water Prepared by Combining Electrospinning and Hot-Pressing Methods. ACS Polym. Au 2025, 5, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Agarwal, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Prajapati, S.K.; Kumar, T.; Singhal, N. Waste Clothes to Microcrystalline Cellulose: An Experimental Investigation. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 31, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, X.; Hou, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, B. Fabrication of low-cost, self-floating, and recyclable Janus nanofibrous membrane by centrifugal spinning for photodegradation of dyes. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 685, 133181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Lu, T.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Lei, J.; Ma, W.; Zou, Y.; Huang, C. Flexible and transparent composite nanofibre membrane that was fabricated via a “green” electrospinning method for efficient particulate matter 2.5 capture. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 582, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sheng, J.; Yao, Y.; Yan, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Tang, Z.; Li, H. Fluorine-Free Hydrophobic Modification and Waterproof Breathable Properties of Electrospun Polyacrylonitrile Nanofibrous Membranes. Polymers 2022, 14, 5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, G.; Nie, G.; Hu, S.; Li, D.; Sun, W.; Li, Z.; Cui, Z.; Lu, D.; Shi, X.; et al. Facile fabrication of fluorine-free waterproof and breathable nanofiber membranes with UV-resistant and acid-alkali resistant performances. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 685, 133310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, N.-R.; Lu, C.; Guan, J.; Lee, L.J.; Epstein, A.J. Growth and alignment of polyaniline nanofibres with superhydrophobic, superhydrophilic and other properties. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Yan, Y.; Guan, X.; Huang, K. Preparation of a hordein-quercetin-chitosan antioxidant electrospun nanofibre film for food packaging and improvement of the film hydrophobic properties by heat treatment. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 23, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, X. Cellulose acetate butyrate/cellulose Janus nanofiber membrane for unidirectional moisture conduction. Cellulose 2025, 32, 10613–10624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Deng, C.; Li, C.; Du, Y.; Zhu, M. Multi-hierarchical nanofibre membranes composited with ordered structure/nano-spiderwebs for air filtration. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Li, Z.; Hang, T.; Chen, Y.; He, T.; Li, X.; Zheng, J.; Wu, Z. Multi-Scale MXene/Silver Nanowire Composite Foams with Double Conductive Networks for Multifunctional Integration. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2403551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehrani-Bagha, A.R. Waterproof breathable layers—A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 268, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belval, L.N.; Cramer, M.N.; Huang, M.; Moralez, G.; Cimino, F.A.; Watso, J.C.; Crandall, C.G. Interaction Between Exercise Intensity and Burn Size Affects Body Temperature During Exercise in the Heat. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.T.; Barbosa, N.H.S.; Souza-Junior, R.C.S.; Fonseca, C.G.; Damasceno, W.C.; Regina-Oliveira, K.; Drummond, L.R.; Bittencourt, M.A.; Kunstetter, A.C.; Andrade, P.V.R.; et al. Determinants of body core temperatures at fatigue in rats subjected to incremental-speed exercise: The prominent roles of ambient temperature, distance traveled, initial core temperature, and measurement site. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2023, 67, 761–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Ji, B.; Xu, F.; Huang, J.; Miao, Y.E.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T. Thermal Rectification in Gradient Microfiber Textiles Enabling Noncontact and Contact Dual-Mode Radiative Cooling. Small 2025, 21, 2503420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Duan, C.; Ma, R.; Liu, X.; Meng, Z.; Xie, Z.; Ni, Y. Smart and Robust Phase Change Cellulose Fibers from Coaxial Wet-Spinning of Cellulose Nanofibril-Reinforced Paraffin Capsules with Excellent Thermal Management. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 346, 122649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Lyu, G. Influence of Urban Atmospheric Ecological Environment on the Development of Outdoor Sports. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1931075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, T.; Li, T.-T.; Lin, J.-H. Flexible Piezoelectric Sensors Based on Electrostatically Spun PAN/K-BTO Composite Films for Human Health and Motion Detection. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 5855–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Xin, B.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y. Characterization and Mechanism Analysis of Flexible Polyacrylonitrile-Based Carbon Nanofiber Membranes Prepared by Electrospinning. Fibers Polym. 2023, 24, 4195–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-D.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Xu, T.-Z.; Abadikhah, H.; Wang, J.-W.; Xu, X.; Agathopoulos, S. Fabrication and characterization of robust hydrophobic lotus leaf-like surface on Si3N4 porous membrane via polymer-derived SiNCO inorganic nanoparticle modification. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 16443–16449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Data monitoring for a physical health system of elderly people using smart sensing technology. Wirel. Netw. 2023, 29, 3665–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. Developing a wearable human activity recognition (WHAR) system for an outdoor jacket. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2023, 35, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K. Environmental preferences and consumer behavior. Econ. Lett. 2016, 149, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, R.; Xu, G.; Zeng, J.; Guo, R.; Wei, X.; Wang, H. Nanofibrous membrane through multi-needle electrospinning with multi-physical field coupling. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 075012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, M.; Fan, Y.; Xie, N.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, W. Construction of Electrospinning Janus Nanofiber Membranes for Efficient Solar-Driven Membrane Distillation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 305, 122348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Yao, J.; Zhu, G.; Guo, B.; Militky, J.; Kremenakova, D.; Zhang, M. Nanofibrous membranes with hydrophobic and thermoregulatory functions fabricated by coaxial electrospinning. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e54677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, T. Electrospun MXene-based nanofibrous membranes: Multifunctional integration, challenges, and emerging applications. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 208, 109480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lin, M.; Wang, Y.; Ding, X.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Yang, W. The Preparation of Polyvinyl Chloride Nanofiber Membrane by Melt Electrospinning for Ester Plasticizer Adsorption. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, L.; Zhou, M.; Ma, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Drioli, E.; Cheng, X. Recent progress on functional electrospun polymeric nanofiber membranes. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Effect on Fiber Morphology | Optimization Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solution Properties | Concentration/Viscosity | Too low (8 wt%) tends to form beads, while too high (20 wt%) increases the diameter and may even clog the nozzle; viscosity is often positively correlated with fiber diameter. | Adjust to 2–2.5 times the critical concentration range, with the optimal spinning concentration being approximately 4–5 wt%. |

| Elasticity/Relaxation Characteristics | Affects the stability and stretching behavior of the jet. High elasticity suppresses the bending instability of the jet, facilitating the formation of straighter and more uniform fibers; excessively low elasticity may lead to jet breakage or the formation of irregular fibers. | Select polymers with appropriate molecular weight/structure or add plasticizers for adjustment. | |

| Electrical conductivity | Increased electrical conductivity leads to reduced fiber diameter | Add an appropriate amount of salt or ionic liquid | |

| Surface Tension | Reducing surface tension helps initiate jetting | Adding an appropriate amount of surfactant | |

| Process Parameters | Voltage | As voltage increases, the diameter first decreases and then increases, with the distribution broadening | Identify the optimal voltage value, typically 1.2–2 times the critical voltage. For many systems, optimize within the range of 10–20 kV. |

| Receiving distance | Distance affects stretching and volatilization degree | Adjust according to solvent volatilization rate, commonly within the range of 10–20 cm. For low-volatility solvents, a longer distance is required (~20 cm); for high-volatility solvents, the distance can be shorter (~12 cm). | |

| Solution flow rate | Flow rate increases, diameter increases | Under the condition of ensuring a continuous jet, the flow rate is typically reduced to 0.1–2.0 mL/h. | |

| Environmental conditions | Temperature | Affect solvent evaporation rate | Adjust according to the solvent boiling point (Tb), usually controlled within the range of Tb ± 10 °C. |

| Humidity | Excessive levels leading to fiber moisture absorption or formation of porous structures | Control humidity based on material hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity: hydrophobic polymers can be electrospun at higher RH (40%–60%) to induce porous structures; hydrophilic polymers require low RH (<30%) to prevent moisture absorption and adhesion. | |

| Airflow velocity | Affecting volatilization kinetics | Maintain stable low-speed airflow (<0.5 m/s) |

| Material Type | Hydrostatic Pressure (kPa) | Moisture Vapor Transmission Rate (g·m−2·24 h−1) | Contact Angle (°) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPU Nanofiber Membrane | 85–120 | 8000–12,000 | 130–145 | High elasticity, good comfort |

| PVDF Nanofiber Membrane | 110–150 | 6000–10,000 | 140–155 | Excellent chemical resistance, high waterproof performance |

| CA/PVA Composite Membrane | 70–100 | 5000–8000 | 125–140 | Biodegradable, environmentally friendly |

| PTFE Nanofiber Membrane | 130–180 | 9000–13,000 | 150–165 | Excellent durability, long-term stability |

| Commercial Gore-Tex Membrane | 90–140 | 8000–10,000 | 135–150 | Mature technology with balanced comprehensive performance |

| Response Type | Representative Materials | Stimulus Conditions | Response Mechanisms | Performance Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Response | PNIPAm and its Copolymers | Temperature Exceeds LCST | Hydrophilic-Hydrophobic Transition | Pore structure variation, Ag+ controlled release |

| Humidity responsiveness | Methyl cellulose/IPN hydrogel | Relative humidity 50%–100% | Asymmetric swelling/shrinkage | Directional moisture transport, breathability regulation |

| pH responsiveness | Chitosan/polyacrylic acid | pH varies within the range of 4–8 | Protonation/Deprotonation | Pore size variation, controlled drug release |

| Photothermal response | Graphene/PNIPAm composite | UV-visible light irradiation | Photothermal conversion induced phase transition | Reversible wettability, color change |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yan, G.; Hu, Y.; Liu, M.; Huang, F.; Miu, J.; Huang, G. Application of Electrospun Nanofiber Membranes in Outdoor Sportswear: From Preparation Technologies to Multifunctional Integration. Coatings 2026, 16, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010029

Yan G, Hu Y, Liu M, Huang F, Miu J, Huang G. Application of Electrospun Nanofiber Membranes in Outdoor Sportswear: From Preparation Technologies to Multifunctional Integration. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Guobao, Yangxian Hu, Mingxing Liu, Fawei Huang, Jinghua Miu, and Guoyuan Huang. 2026. "Application of Electrospun Nanofiber Membranes in Outdoor Sportswear: From Preparation Technologies to Multifunctional Integration" Coatings 16, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010029

APA StyleYan, G., Hu, Y., Liu, M., Huang, F., Miu, J., & Huang, G. (2026). Application of Electrospun Nanofiber Membranes in Outdoor Sportswear: From Preparation Technologies to Multifunctional Integration. Coatings, 16(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010029