Thermal Analysis and Thermal–Mechanical Stress Simulation of Polycrystalline Diamond Compact Bits During Rock Breaking Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

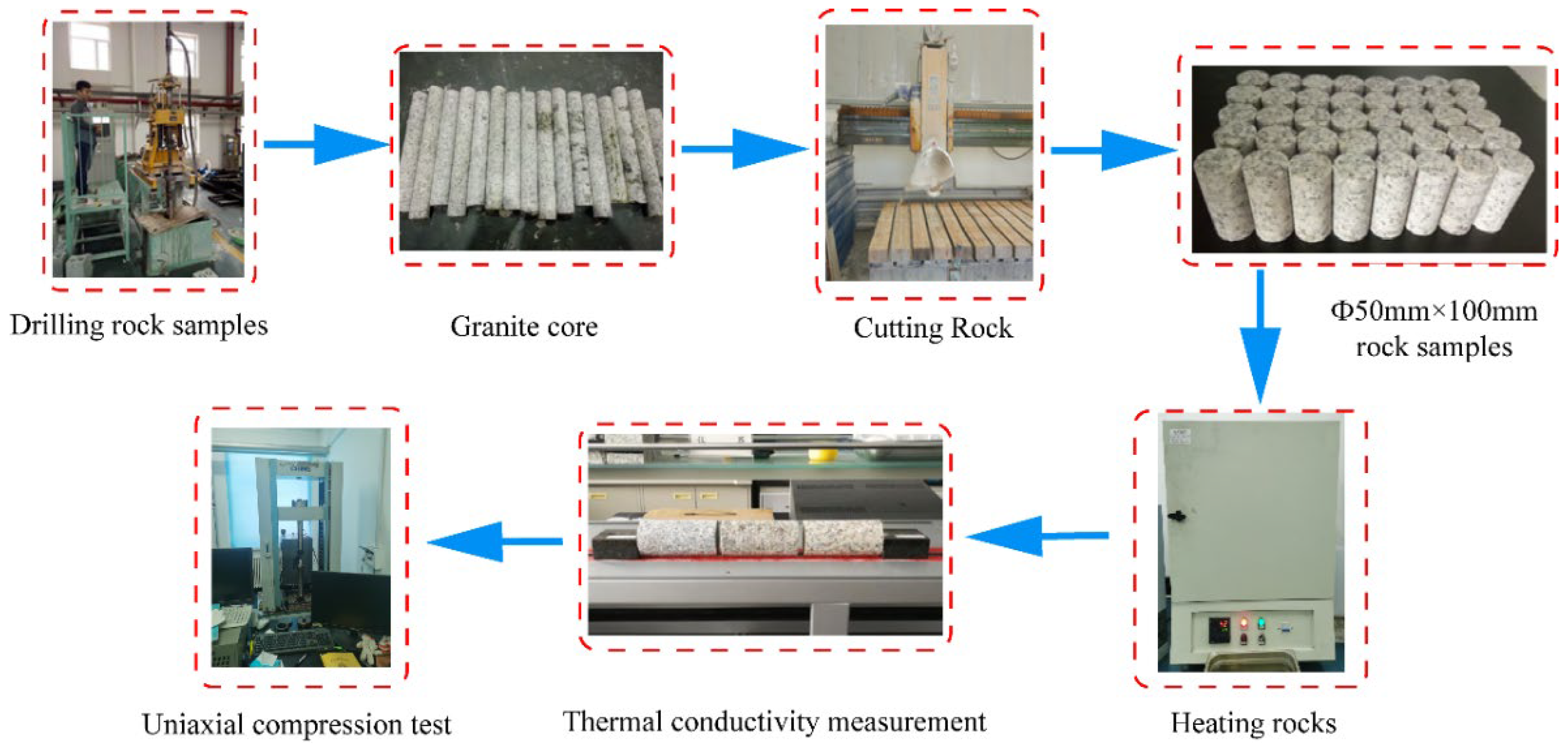

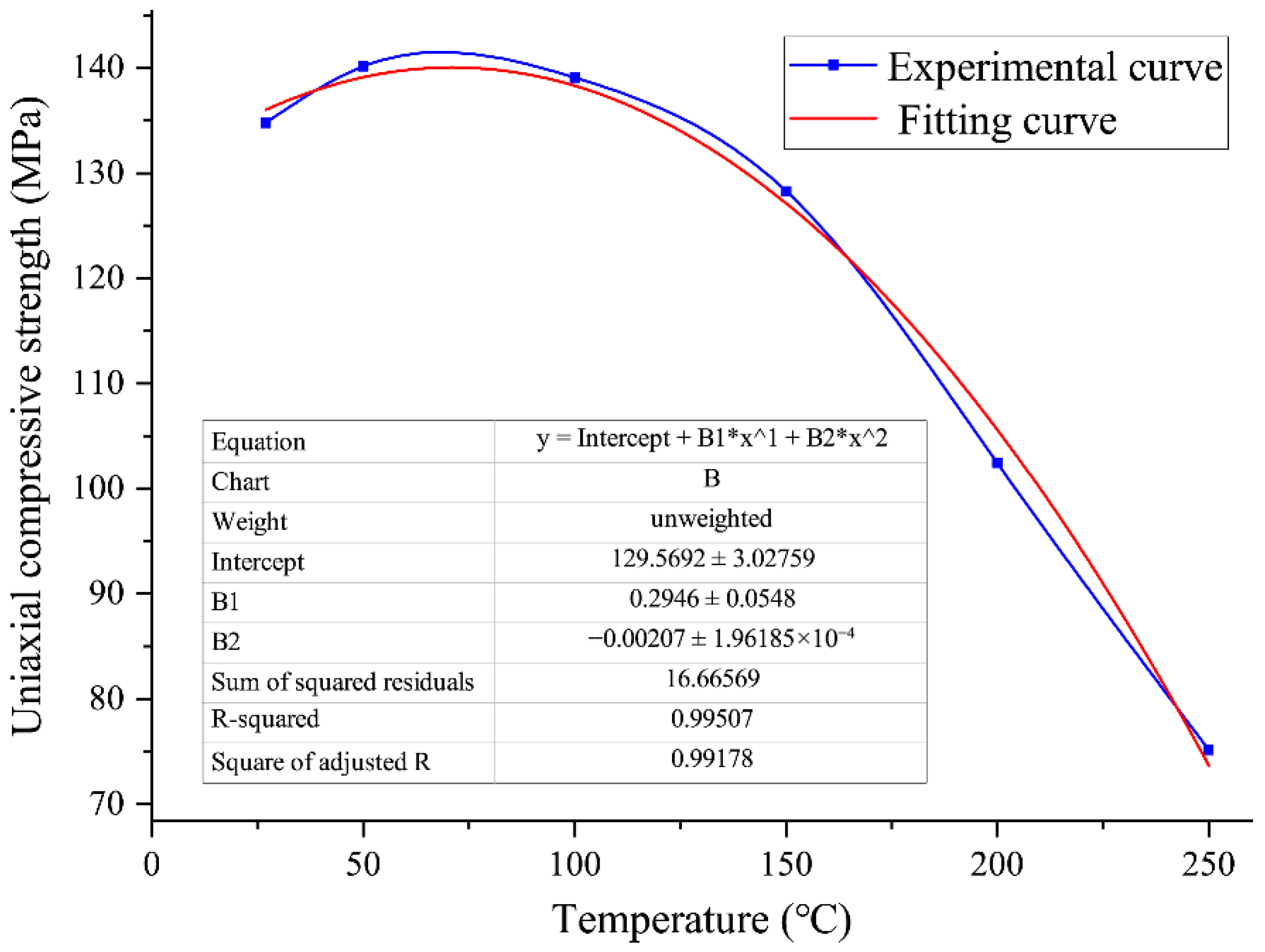

2. Rock Mechanics Parameters

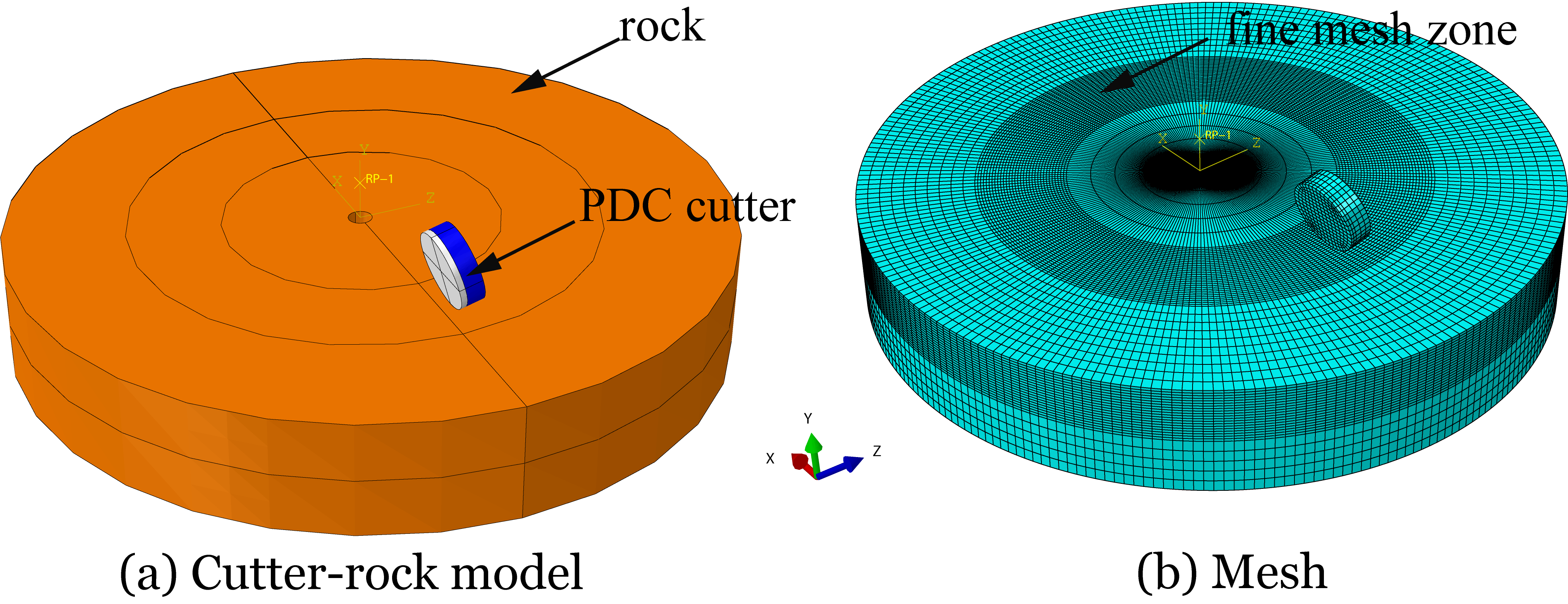

3. Finite Element Modeling of the Rock-Breaking Process

3.1. Model Assumption

- (1)

- The PDC cutter and rock are homogeneous continuous media, and the effects of the pore medium were ignored.

- (2)

- Only vertical and rotary motions were considered in the rock-breaking process of the PDC cutter; lateral motions and oscillations were not considered without considering lateral and swinging movements.

- (3)

- The influence of the thermal convection and radiation between the bit, rock, and surrounding environmental medium were ignored.

3.2. Simulation Setup

3.3. Boundary and Load

4. Simulation Results and Discussion

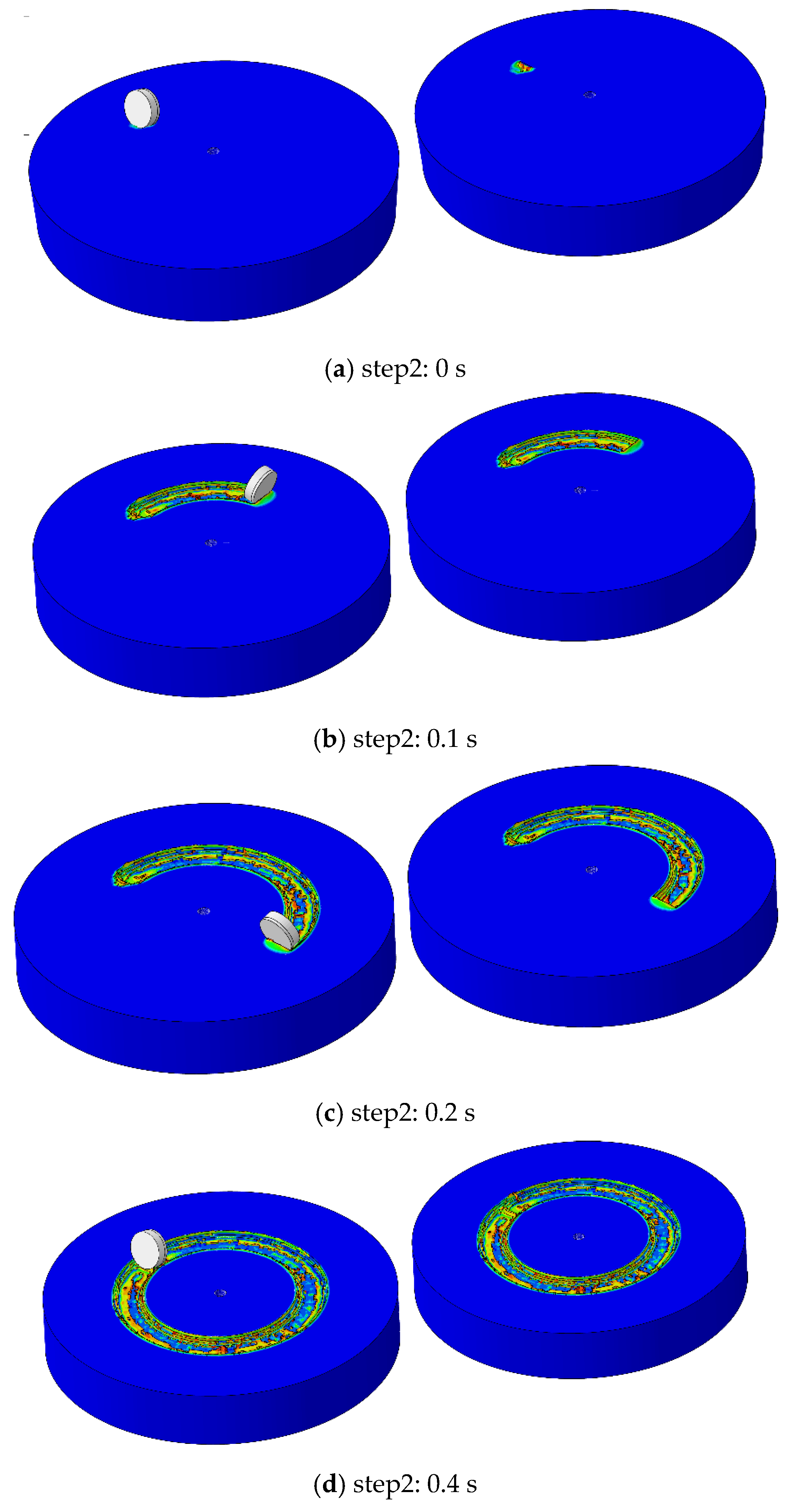

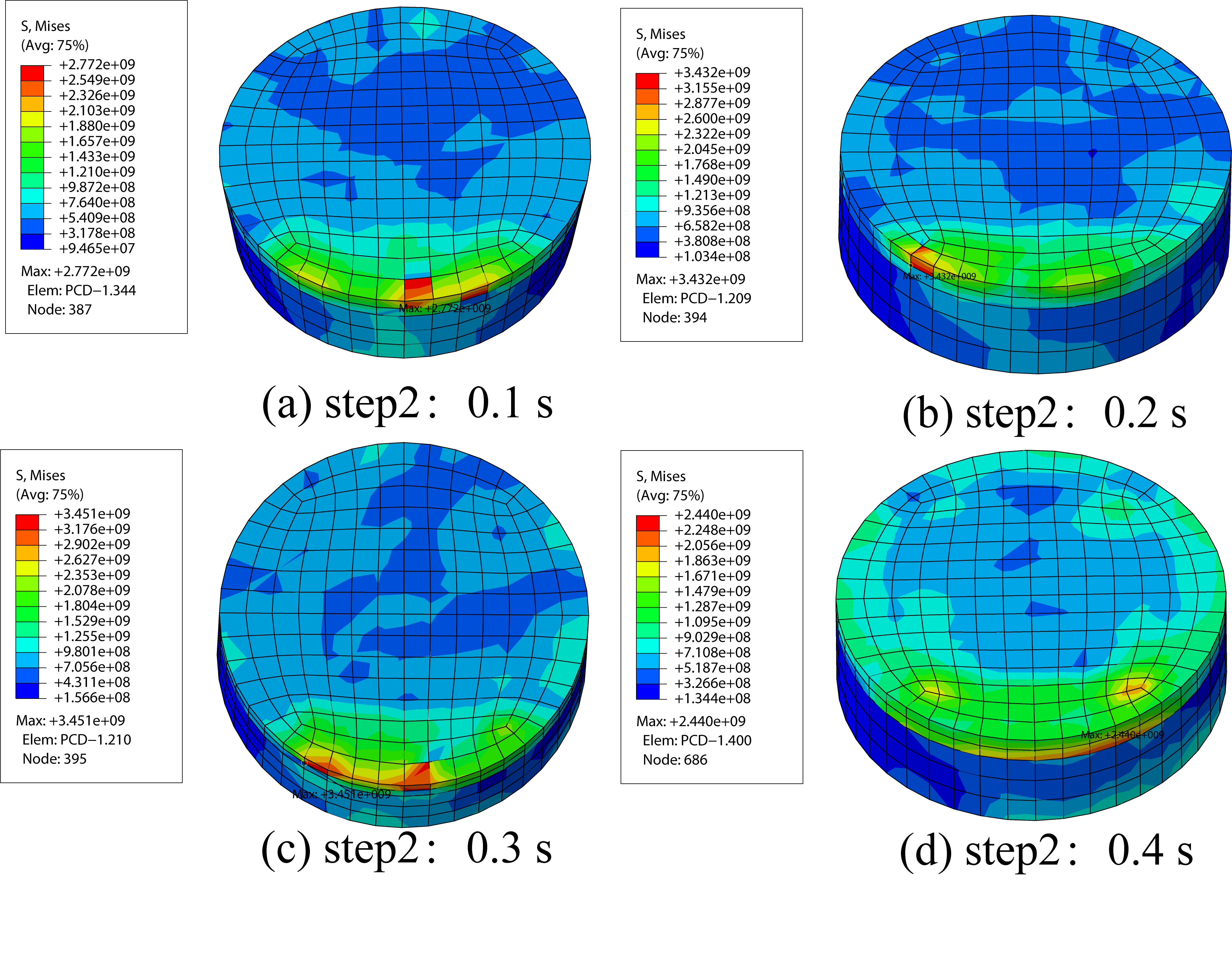

4.1. Analysis of Rock Breaking

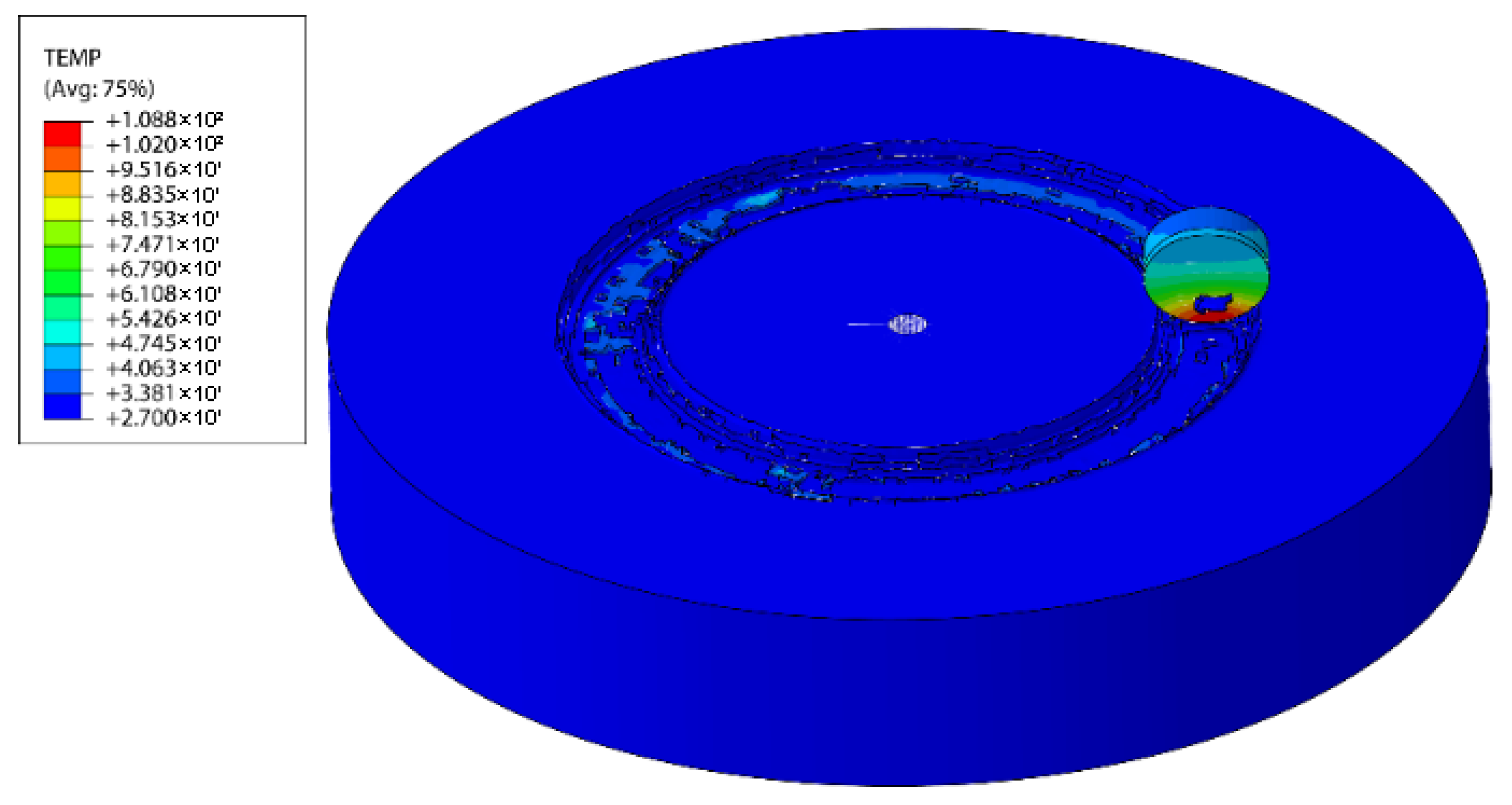

4.2. Temperature Field of the PDC Cutter

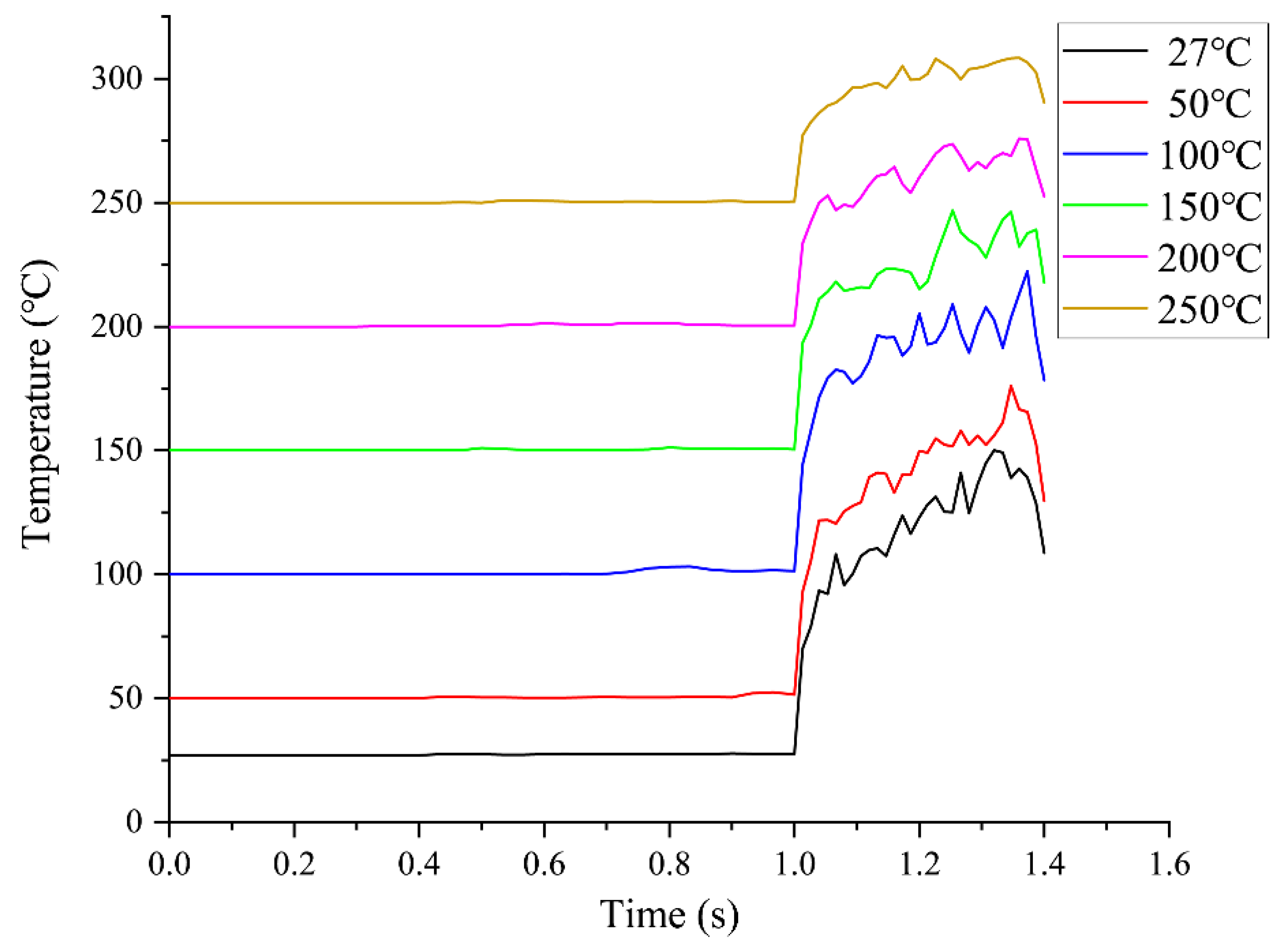

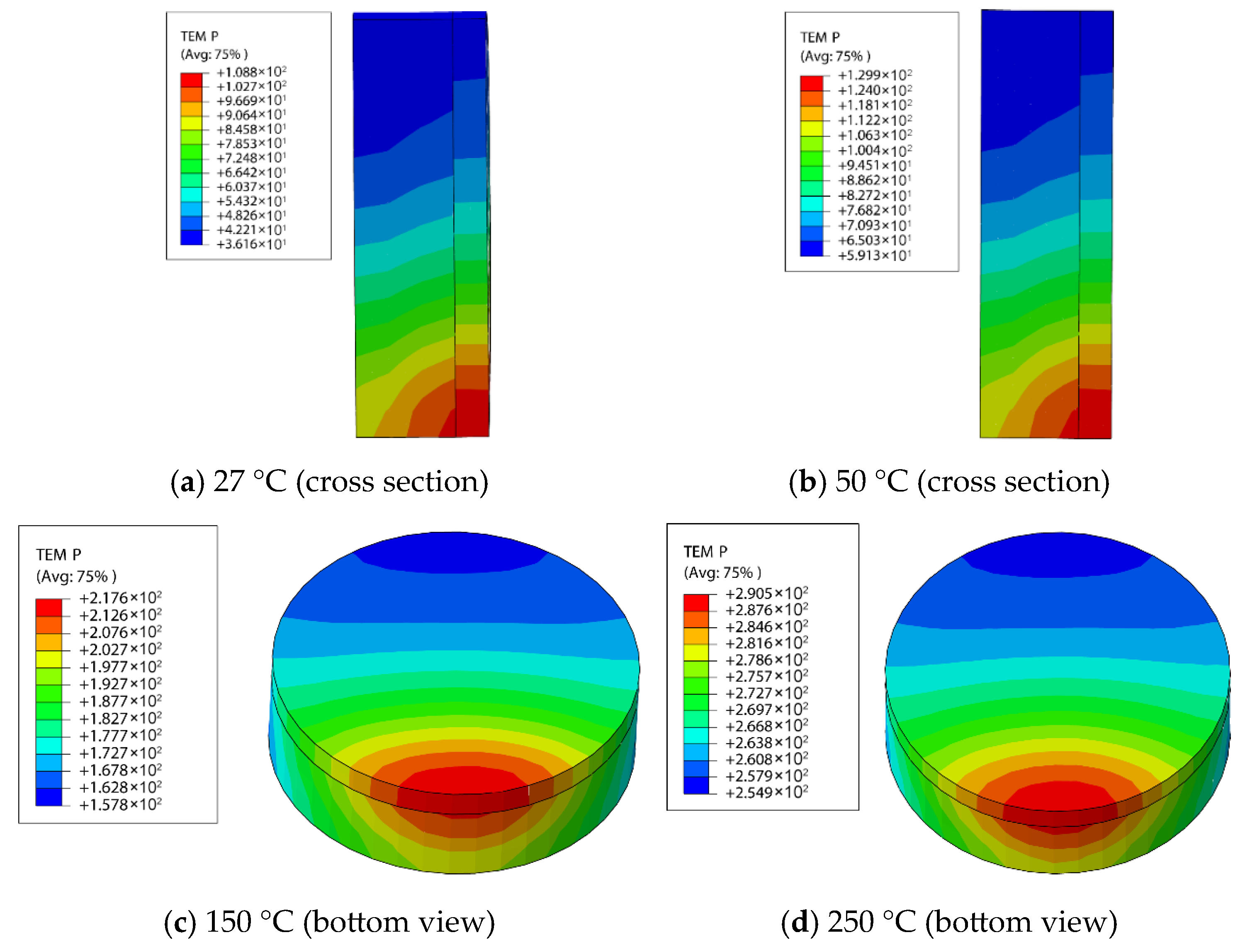

4.2.1. Effect of Formation Temperature

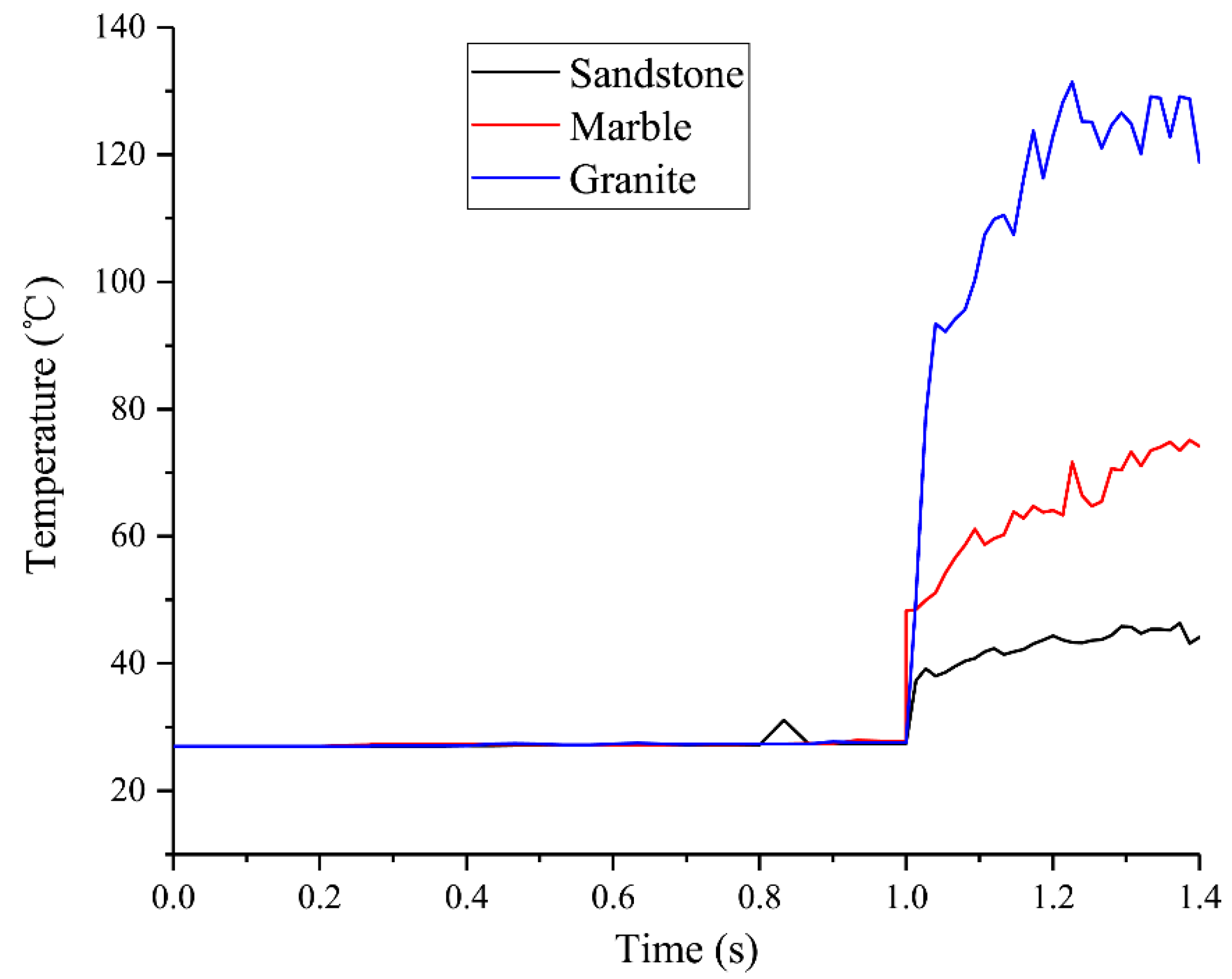

4.2.2. Effect of Rock Strength

4.3. Thermal Stress Field of the PDC Cutter

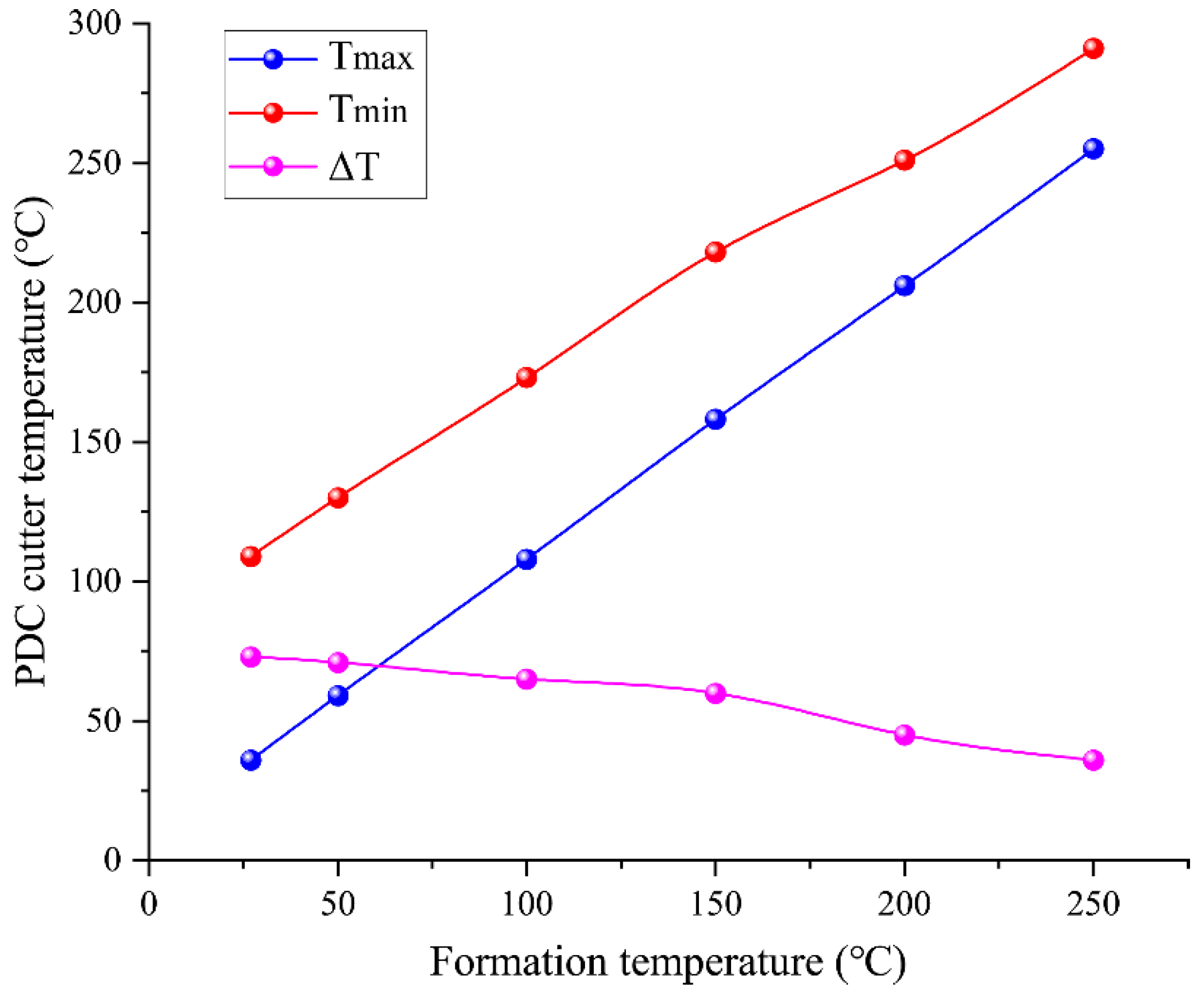

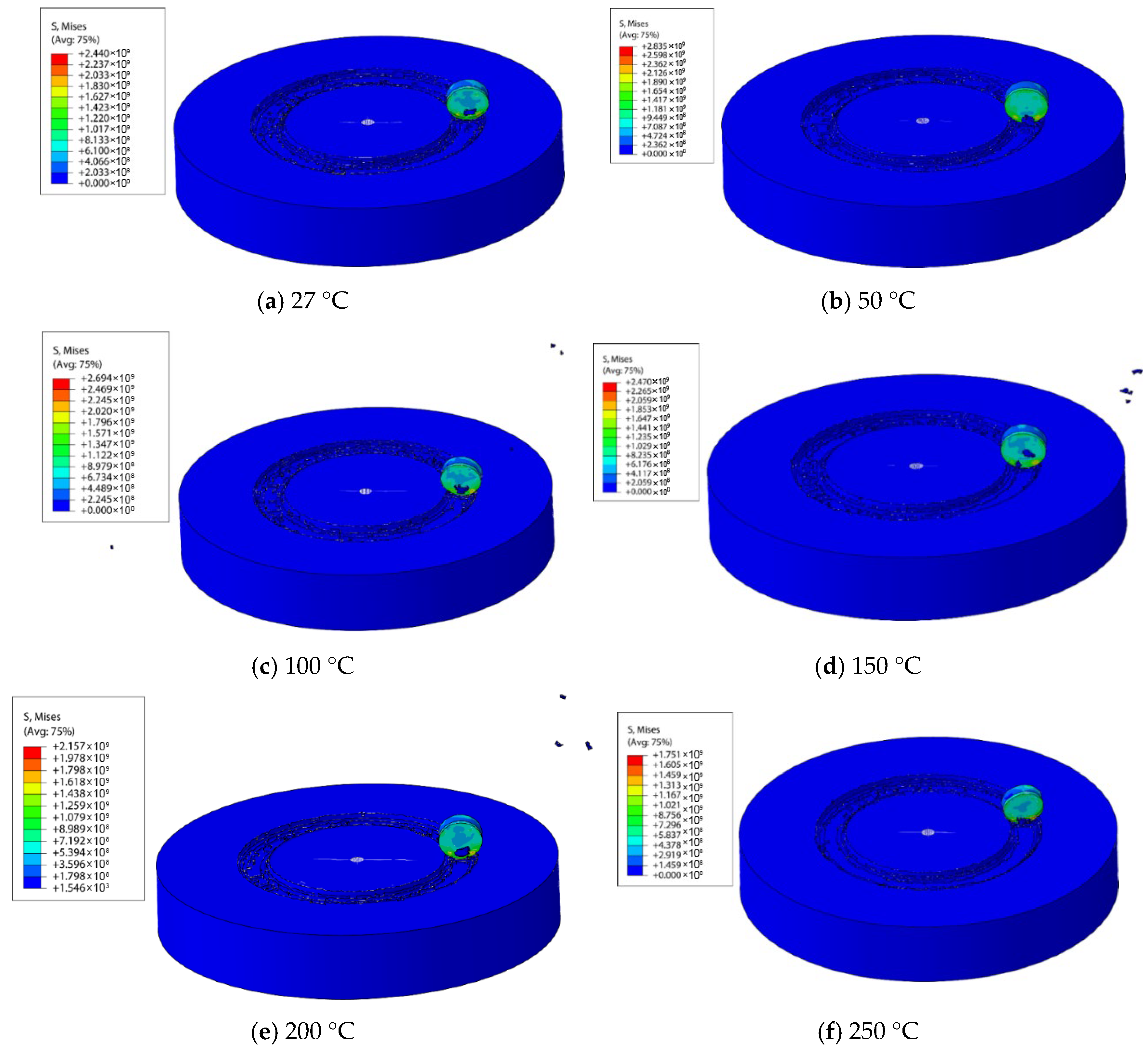

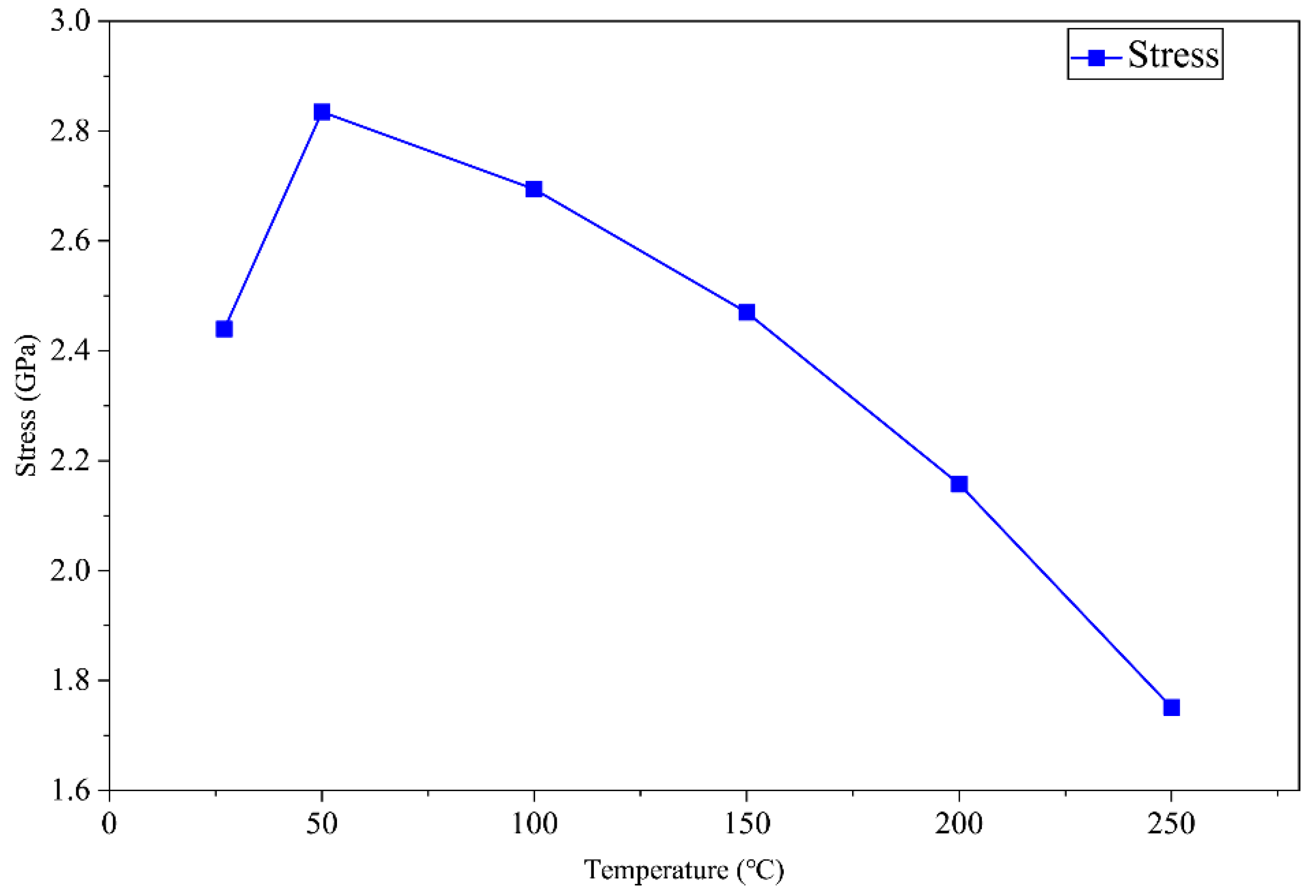

4.3.1. Effect of Formation Temperature

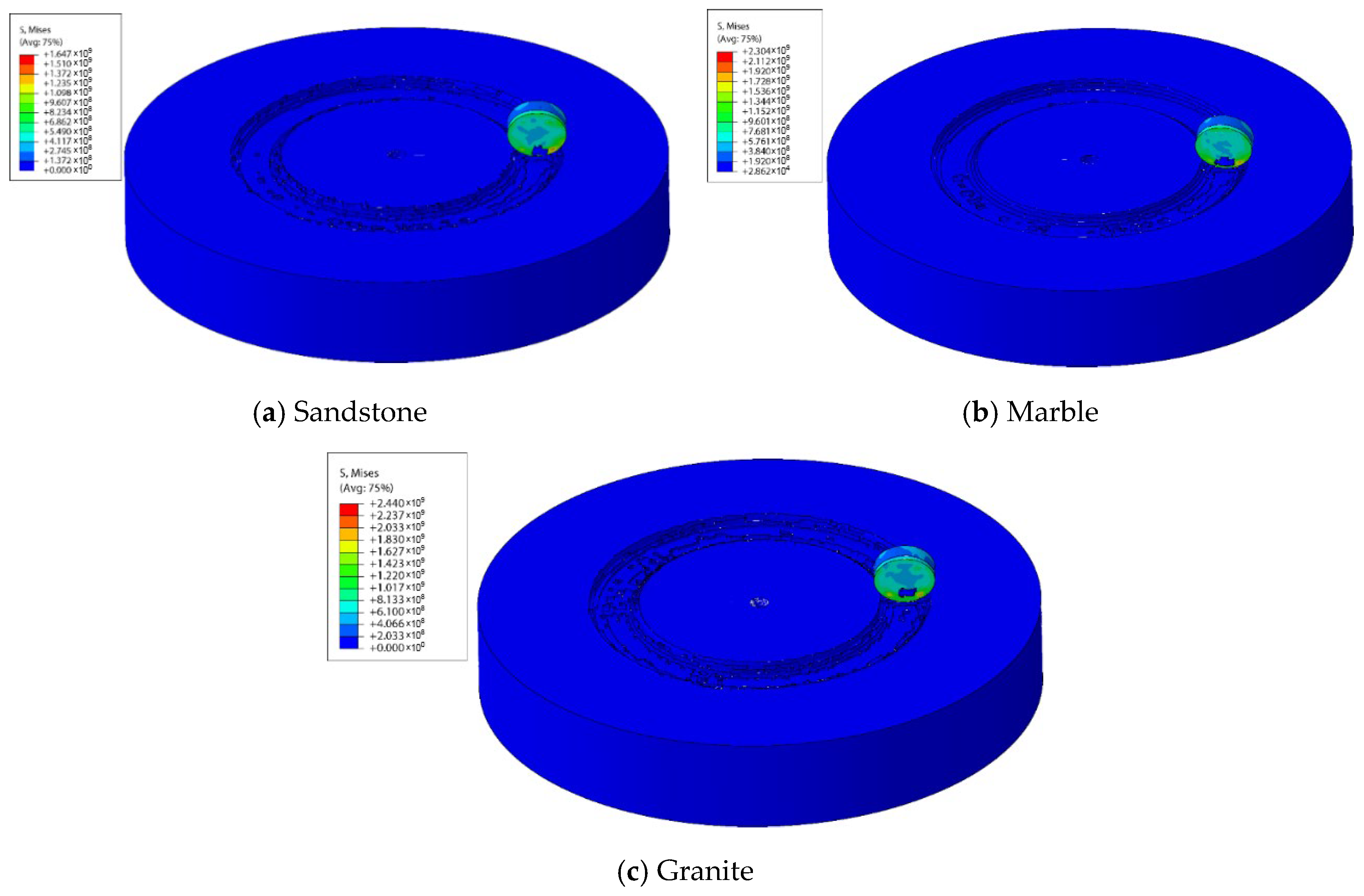

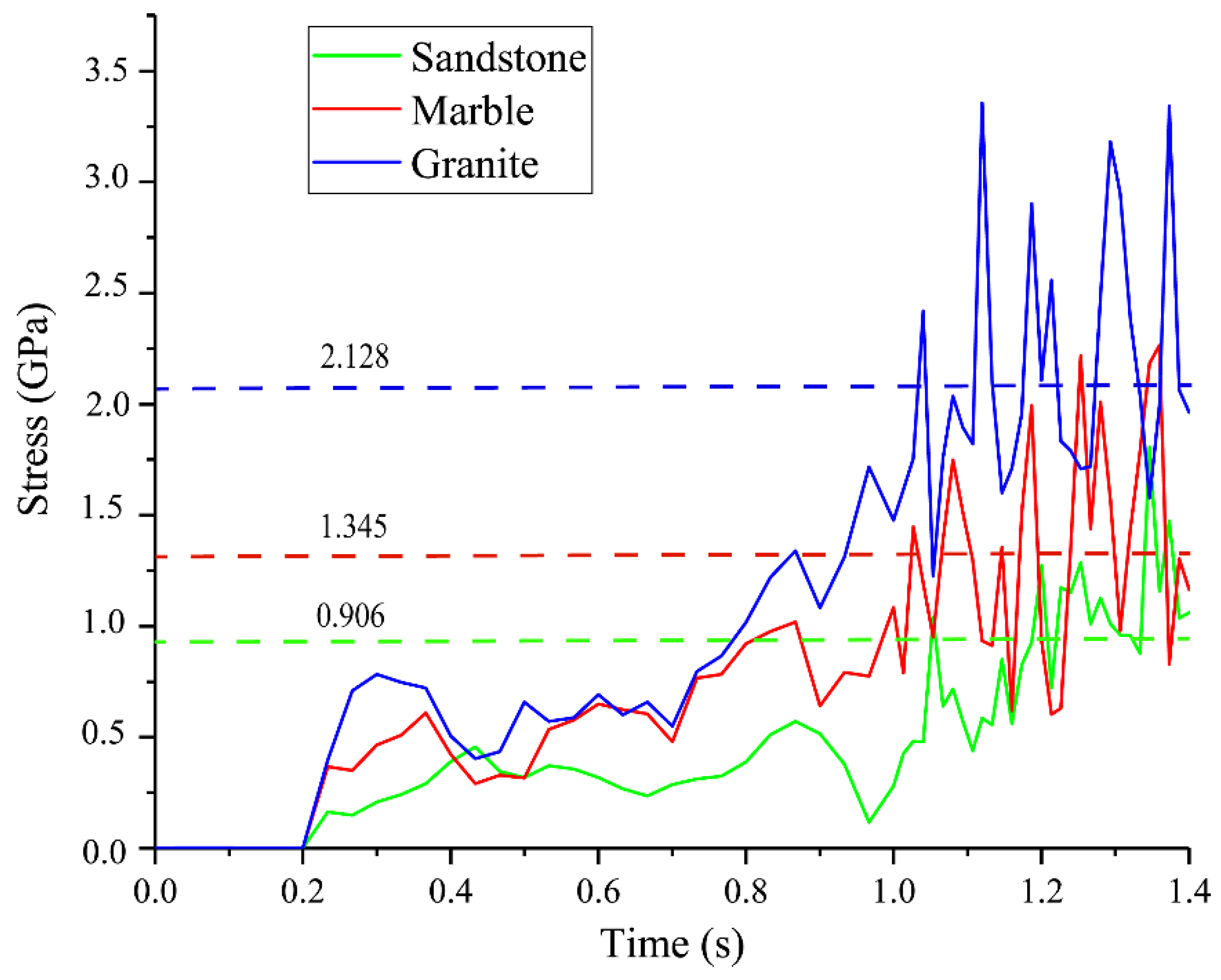

4.3.2. Effect of Rock Strength

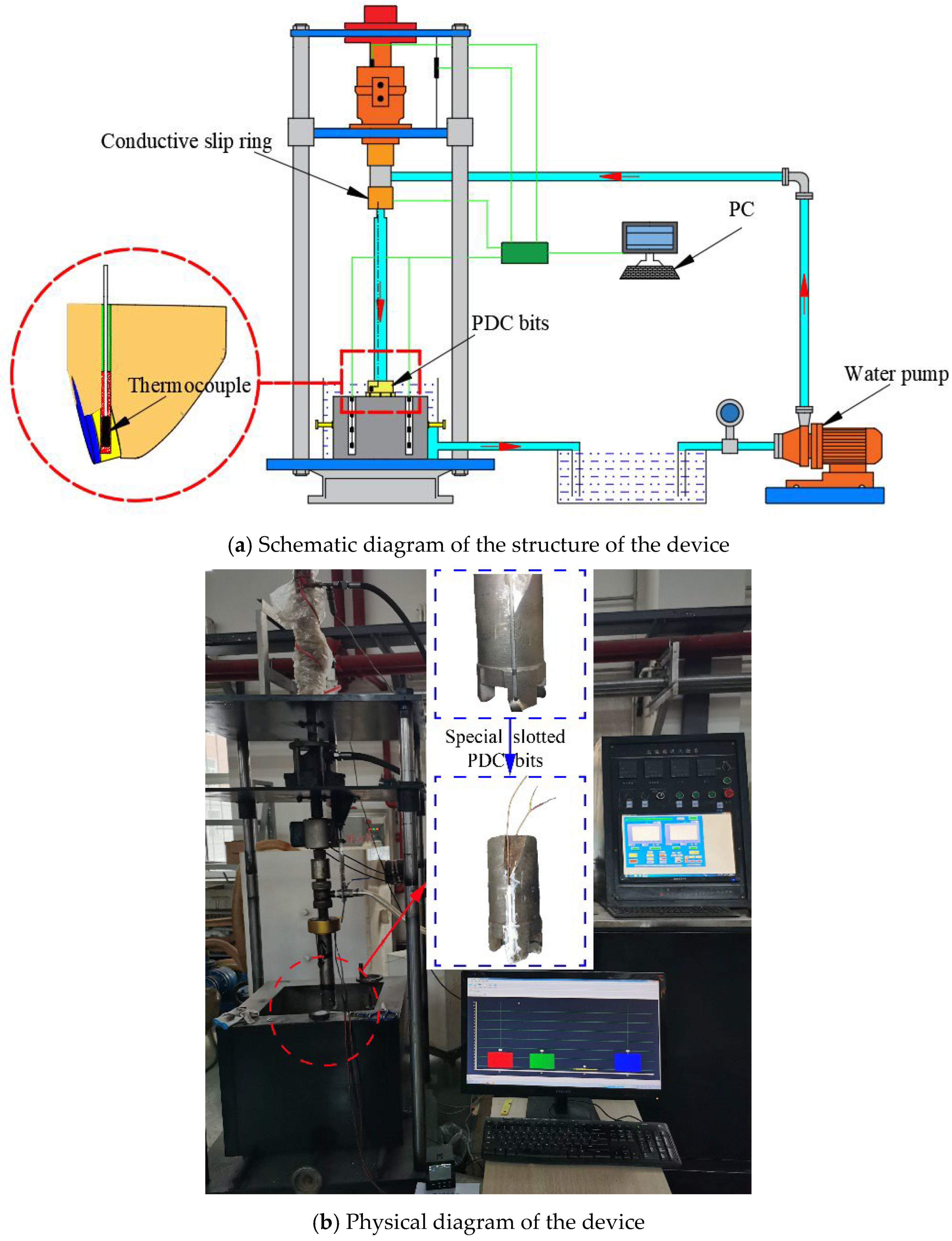

5. Experimental Setup

5.1. Experimental Devices

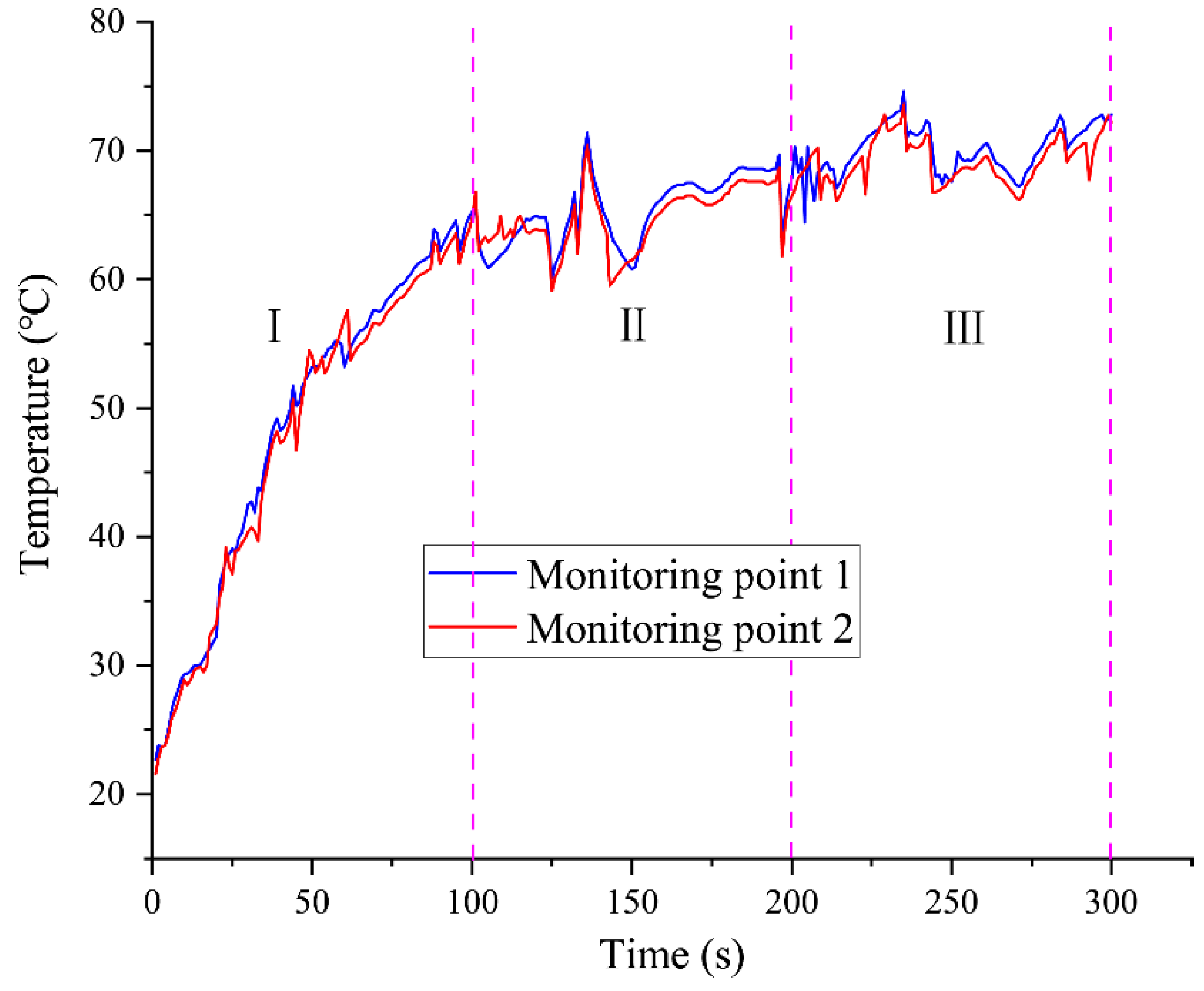

5.2. Experimental Results

5.3. Breaking Hig- Temperature Rock

6. Conclusions

- (1)

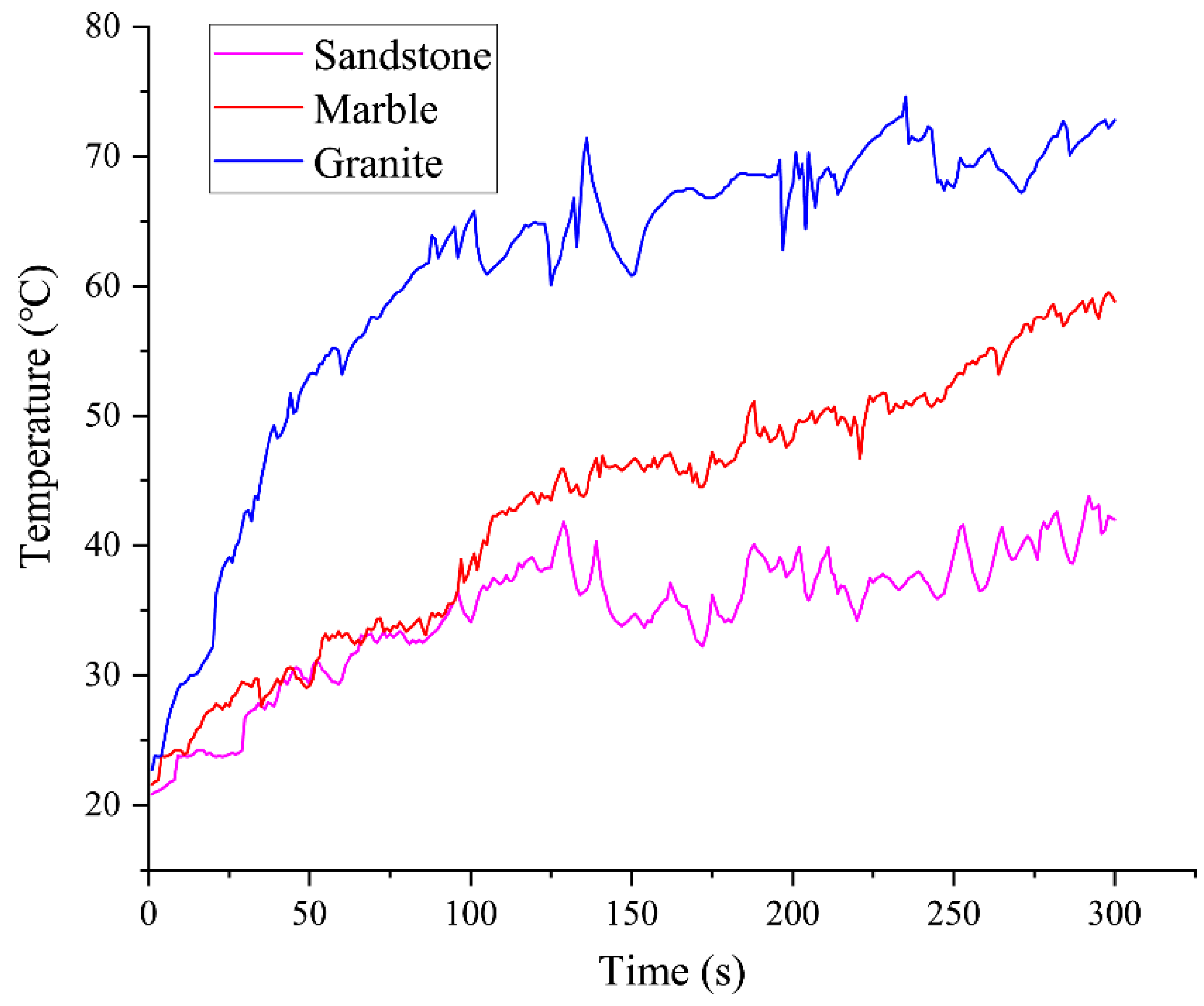

- The temperature rise of a PDC cutter during rock breaking exhibits a consistent three-stage pattern as follows: rapid increase, slow increase, and stabilization. Rock strength is a dominant factor influencing the rate of temperature rise and the magnitude of cutter temperature. When breaking granite (uniaxial compressive strength ≈ 134.8 MPa at 27 °C), the cutter temperature reached approximately 131.4 °C, about two and three times higher than when cutting marble (≈75.2 °C) and sandstone (≈46.3 °C), respectively. Correspondingly, the rate of penetration (ROP) decreased by 70.6% and 75.6% when drilling granite compared to marble and sandstone.

- (2)

- Increasing formation temperature reduces the internal temperature gradient within the cutter, thereby mitigating thermal stress. As the formation temperature rose from 27 °C to 250 °C, the temperature difference between the maximum and minimum points on the cutter decreased from 72.6 °C to 35.6 °C. However, due to material heterogeneity and differential thermal expansion, significant thermal stress still develops, with the maximum equivalent stress (2.84 GPa) occurring at a formation temperature of 50 °C.

- (3)

- The stress distribution in the PDC cutter is highly concentrated at the crown and at the interface between the diamond layer and the tungsten carbide matrix. Both the magnitude and fluctuation amplitude of stress increase with rock strength. The average stress when breaking granite (2.128 GPa) was 58.2% and 134.8% higher than when breaking marble (1.345 GPa) and sandstone (0.906 GPa), respectively. Stress evolution during cutting shows an initial sharp increase followed by fluctuations, with greater instability observed in harder rocks.

- (4)

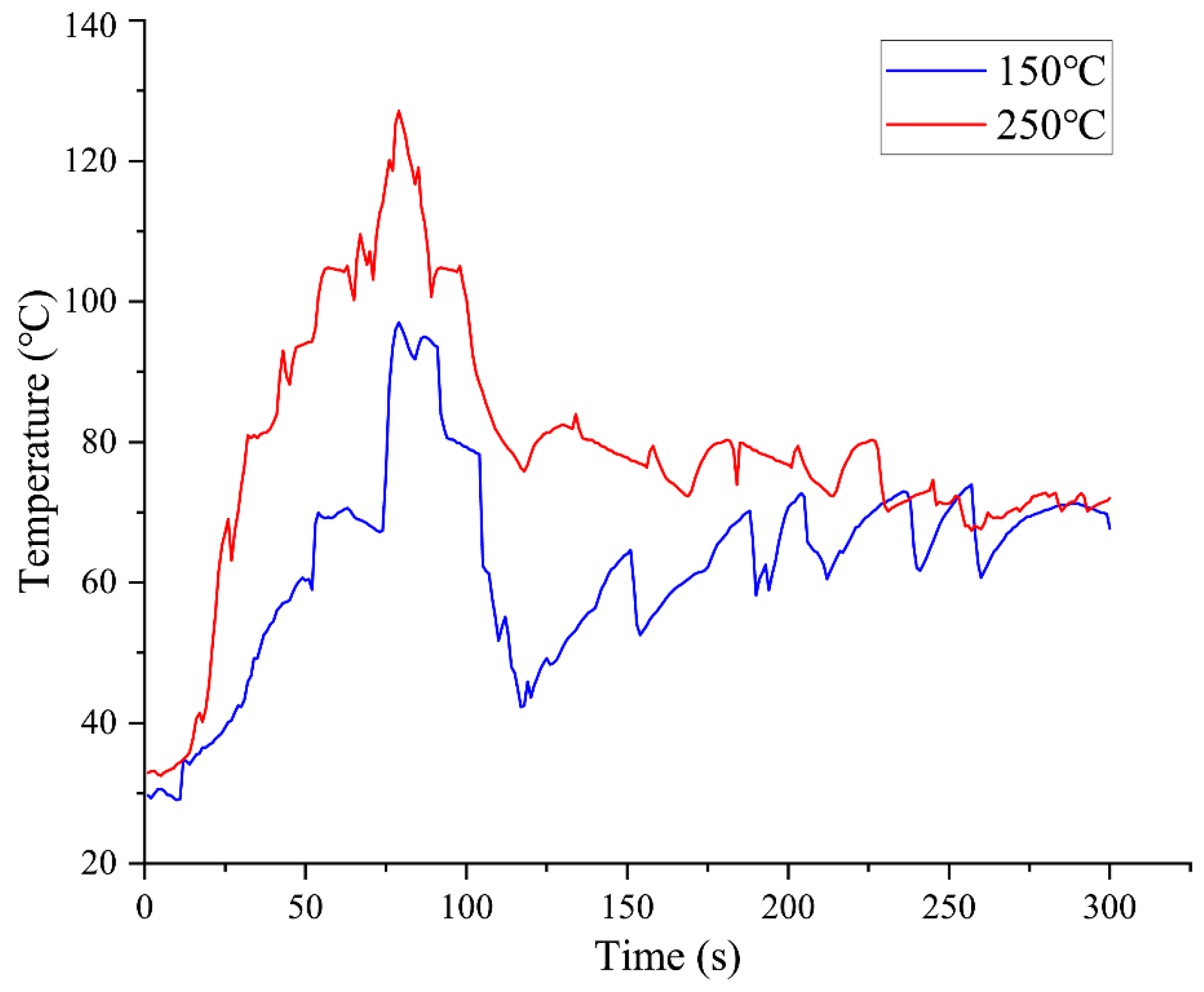

- High formation temperatures alter the rock failure mode from brittle to plastic, which affects cutting efficiency. Although rock strength decreases at elevated temperatures (e.g., granite compressive strength dropped from 134.8 MPa at 27 °C to 75.1 MPa at 250 °C), the increased plasticity can lead to a “rubber layer effect,” reducing the ROP. The highest ROP (0.06 mm/s) was observed at 150 °C, compared to 0.044 mm/s at 27 °C and 0.052 mm/s at 250 °C.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, M.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, H.; Liu, B.; Zheng, G. Numerical investigations on the effect of ultra-high cutting speed on the cutting heat and rock-breaking performance of a single cutter. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 190, 107120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Sun, L.; Ran, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wei, K. Three-dimensional numerical simulation of the straight shale cutting process of single polycrystalline diamond cutter. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Tergeist, M.; Kueck, A.; Ostermeyer, G.-P. Investigation of the cutting force response to a PDC cutter in rock using the discrete element method. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 213, 110330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ling, X.; Pu, H. Development of a Cutting Force Model for a Single PDC Cutter Based on the Rock Stress State. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 53, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ni, H.; Wang, Z.; Huang, B.; Liu, S.; Xu, X.; Liu, C. Discrete element modeling and simulation study on cutting rock behavior under spring-mass-damper system loading. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 209, 109872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Li, G.; Huang, Z.; Sheng, M.; Wu, X.; Yang, J. Analytical modelling of rock cutting force and failure surface in linear cutting test by single PDC cutter. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 177, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, F.; Liu, W.; Gao, D.; Ye, Y. Study on rock-breaking mechanism of axe-shaped PDC cutter. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 205, 108922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Zha, C.; Lian, W.; Gao, R. Numerical investigation on rock-breaking mechanism and cutting temperature of compound percussive drilling with a single PDC cutter. Energy Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 2364–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, A.; Riyaz, M.; Tang, X.; Staack, D.; Tai, B. Specific cutting energy reduction of granite using plasma treatment a feasibility study for future geothermal drilling. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 48, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Huang, Z.; Shi, H.; Shi, X.; Zhang, B.; Chalaturnyk, R. Experimental Investigation into Mixed Tool Cutting of Granite with Stinger PDC Cutters and Conventional PDC Cutters. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 55, 813–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Huang, Z.; Shi, H.; Yang, R.; Dai, X.; He, W. 3D Cutting Force Model of a Stinger PDC Cutter: Considering Confining Pressure and the Thermal Stress. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 5001–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appl, F.C.; Wilson, C.C.; Lakshman, I. Measurement of forces, temperatures and wear of PDC cutters in rock cutting. Wear 1993, 169, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of rock abrasiveness class based on the wear mechanisms of PDC cutters. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 174, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Zhang, P.; Xie, S.; Ren, H.-T.; Zhang, C.-L. Rock breakage and temperature variation of naturally worn PDC tooth during cutting of hard rock and soft rock. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 229, 212042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, B.; Miska, S. The effects of chamfer and back rake angle on PDC cutters friction. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 35, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Dai, X.; Shao, F.; Ozbayoglu, E.; Liu, W.; Wang, J. Review of PDC cutter—Rock interaction: Methods and physics. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 228, 211995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, P.L.; Lovell, M.R.; Avdeev, I.V.; Higgs, C.F. Studies on the formation of discontinuous rock fragments during cutting operation. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2014, 71, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowka, D.A.; Stone, C.M. Thermal Response of Polycrystalline Diamond Compact Cutters Under Simulated Downhole Conditions. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1985, 25, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowka, D.A.; Stone, C.M. Effects of thermal and mechanical loading on PDC bit life. SPE Drill. Eng. 1986, 1, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowka, D.A. The thermal response of rock to friction in the drag cutting process. J. Struct. Geol. 1989, 11, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, D.; Han, P.; Guo, P.; Ehmann, K. Issues in Polycrystalline Diamond Compact Cutter–Rock Interaction From a Metal Machining Point of View—Part I: Temperature, Stresses, and Forces. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2012, 134, 064001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beste, U.; Hartzell, T.; Engqvist, H.; Axen, N. Surface damage on cemented carbide rock-drill buttons. Wear 2001, 249, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Huang, H.; Tang, J. An experimental study of temperature at the tip of point-attack pick during rock cutting process. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 107, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Hirro, K.; Oliveira, D.; Kim, A. Effects of the skew angle of conical bits on bit temperature, bit wear, and rock cutting performance. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 100, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Han, L.; Zou, Y.; Zhu, P.; Liu, B. Polycrystalline diamond compact with enhanced thermal stability. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2017, 33, 1386–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Q.; Han, J. Simulation and experimental study on temperature and stress field of full-sized PDC bits in rock breaking process. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 186, 106679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipold, U.; Huenges, E. Thermal properties of gneisses and amphibolites—High pressure and high temperature investigations of KTB-rock samples. Tectonophysics 1998, 291, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Hou, B. Numerical investigation of mode I fracture toughness anisotropy of deeply textured shale. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 237, 212820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, J.; Fan, B.; Zhao, X.; Jin, F.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Chen, S.; Song, Y.; Yang, J. An intelligent lithology recognition system for continental shale by using digital coring images and convolutional neural networks. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 239, 212909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yao, C.; Guo, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, S. Mineralogical evolution and mechanical degradation of oil well cement under high-temperature and high-pressure CO2 carbonation. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 255, 214112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zeng, B.; He, Y.; Wang, X.; Qian, L.; Xia, C.; Yi, X. Numerical study of rock-breaking mechanism in hard rock with full PDC bit model in compound impact drilling. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 3896–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, A.A.; Antao, D.; Staack, D.; Tai, B.L. Numerical Investigation of the Effect of Pre-induced Cracks on Hard Rock Cutting Using Finite Element Analysis. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 7997–8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Xu, C. Specific Energy as an Index to Identify the Critical Failure Mode Transition Depth in Rock Cutting. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2015, 49, 1461–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, D.M.; Smith, J.; Ehmann, K.F. Finite Element Study of the Cutting Mechanics of the Three Dimensional Rock Turning Process. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2015, 56826, V001T02A021. [Google Scholar]

| Temperature (°C) | Density (kg/m3) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Thermal Conductivity W/(m·°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | 2720 | 40 | 0.25 | 134.771 | 3.15 |

| 50 | 2680 | 38.6 | 0.23 | 140.13 | 3.04 |

| 100 | 2650 | 19.38 | 0.22 | 139.09 | 2.82 |

| 150 | 2670 | 13.76 | 0.20 | 128.275 | 2.64 |

| 200 | 2687 | 11.23 | 0.16 | 102.42 | 2.50 |

| 250 | 2650 | 10.51 | 0.15 | 75.15 | 2.38 |

| Material | Density (kg/m3) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Thermal Conductivity W/(m·°C) | Specific Heat J/(kg·°C) | Thermal Expansion Coefficient (×10−6 °C−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCD | 3510 | 897 | 0.07 | 543.0 | 790 | 2.5 |

| WC-Co | 15,000 | 579 | 0.22 | 100.0 | 230 | 5.2 |

| Sandstone | 2570 | 33.1 | 0.24 | 3.64 | 916.9 | 50 |

| Marble | 2750 | 42.2 | 0.21 | 3.50 | 800 | 4.6 |

| Granite | 2650 | 40 | 0.25 | 3.5 | 800 | 52.0 |

| Type | Time (s) | Footage (mm) | ROP (mm/s) | Maximum Temperature (°C) | Temperature Rise Rate (°C/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandstone | 300 | 54 | 0.18 | 42 | 0.067 |

| Marble | 300 | 45 | 0.15 | 59 | 0.123 |

| Granite | 300 | 13.2 | 0.044 | 75 | 0.177 |

| Type | Time (s) | Footage (mm) | ROP (mm/s) | Maximum Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | 300 | 13.2 | 0.044 | 75 |

| 150 | 300 | 18 | 0.06 | 97 |

| 250 | 300 | 15.6 | 0.052 | 125.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Gao, X.; Liu, J.; Su, T.; Yan, Q.; Dou, F.; Mei, X.; Wang, M. Thermal Analysis and Thermal–Mechanical Stress Simulation of Polycrystalline Diamond Compact Bits During Rock Breaking Process. Coatings 2026, 16, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010030

Zhang Z, Gao X, Liu J, Su T, Yan Q, Dou F, Mei X, Wang M. Thermal Analysis and Thermal–Mechanical Stress Simulation of Polycrystalline Diamond Compact Bits During Rock Breaking Process. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zengzeng, Xiaoting Gao, Jianping Liu, Tian Su, Qing Yan, Fakai Dou, Xuefeng Mei, and Meiyan Wang. 2026. "Thermal Analysis and Thermal–Mechanical Stress Simulation of Polycrystalline Diamond Compact Bits During Rock Breaking Process" Coatings 16, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010030

APA StyleZhang, Z., Gao, X., Liu, J., Su, T., Yan, Q., Dou, F., Mei, X., & Wang, M. (2026). Thermal Analysis and Thermal–Mechanical Stress Simulation of Polycrystalline Diamond Compact Bits During Rock Breaking Process. Coatings, 16(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010030