Preparation and Performance of Nano-Silica-Modified Epoxy Resin Composite Coating for Concrete Subjected to Cryogenic Freeze–Thaw Cycles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments

2.1. Raw Materials

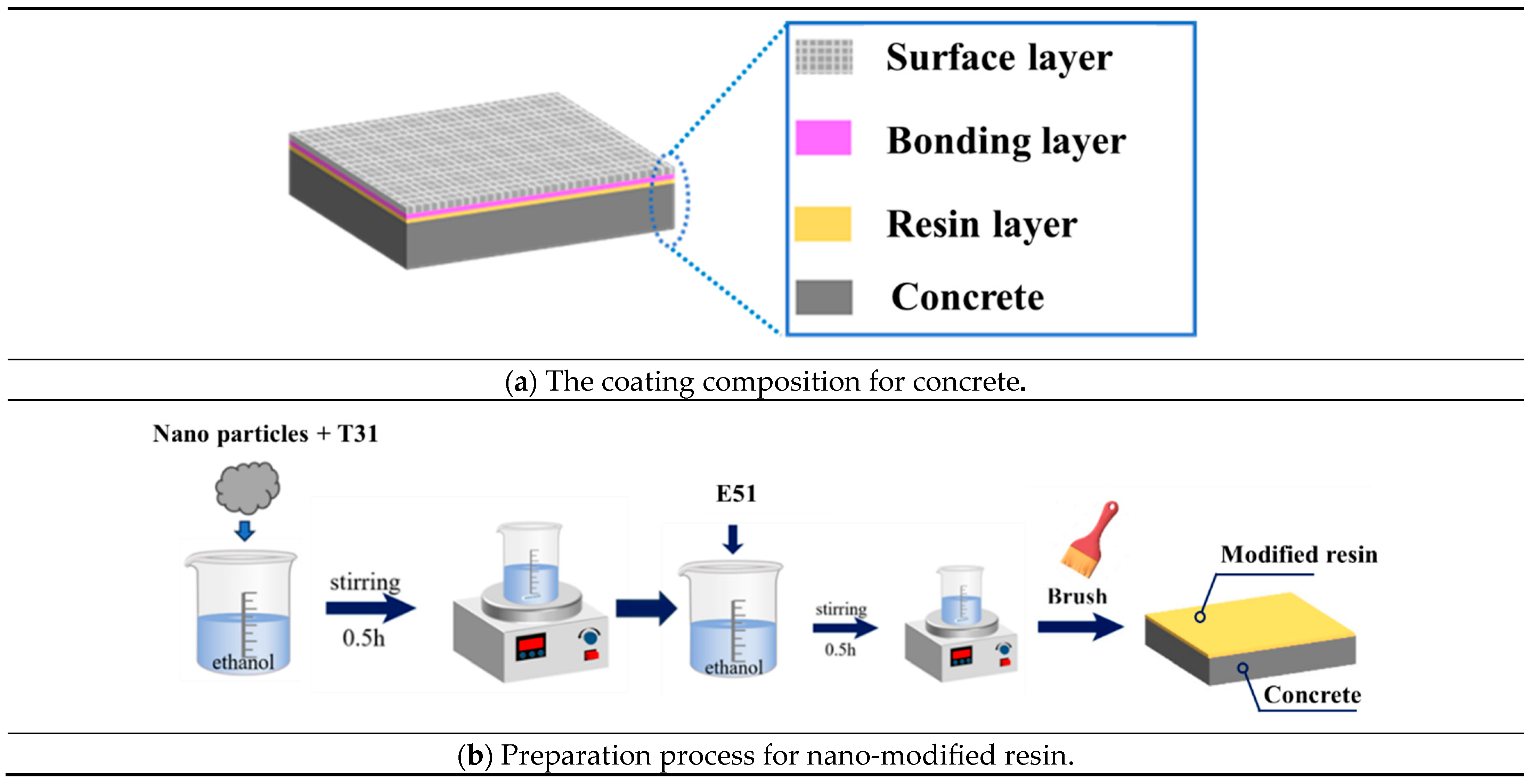

2.2. Preparation of Composite Coating for Concrete

2.3. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

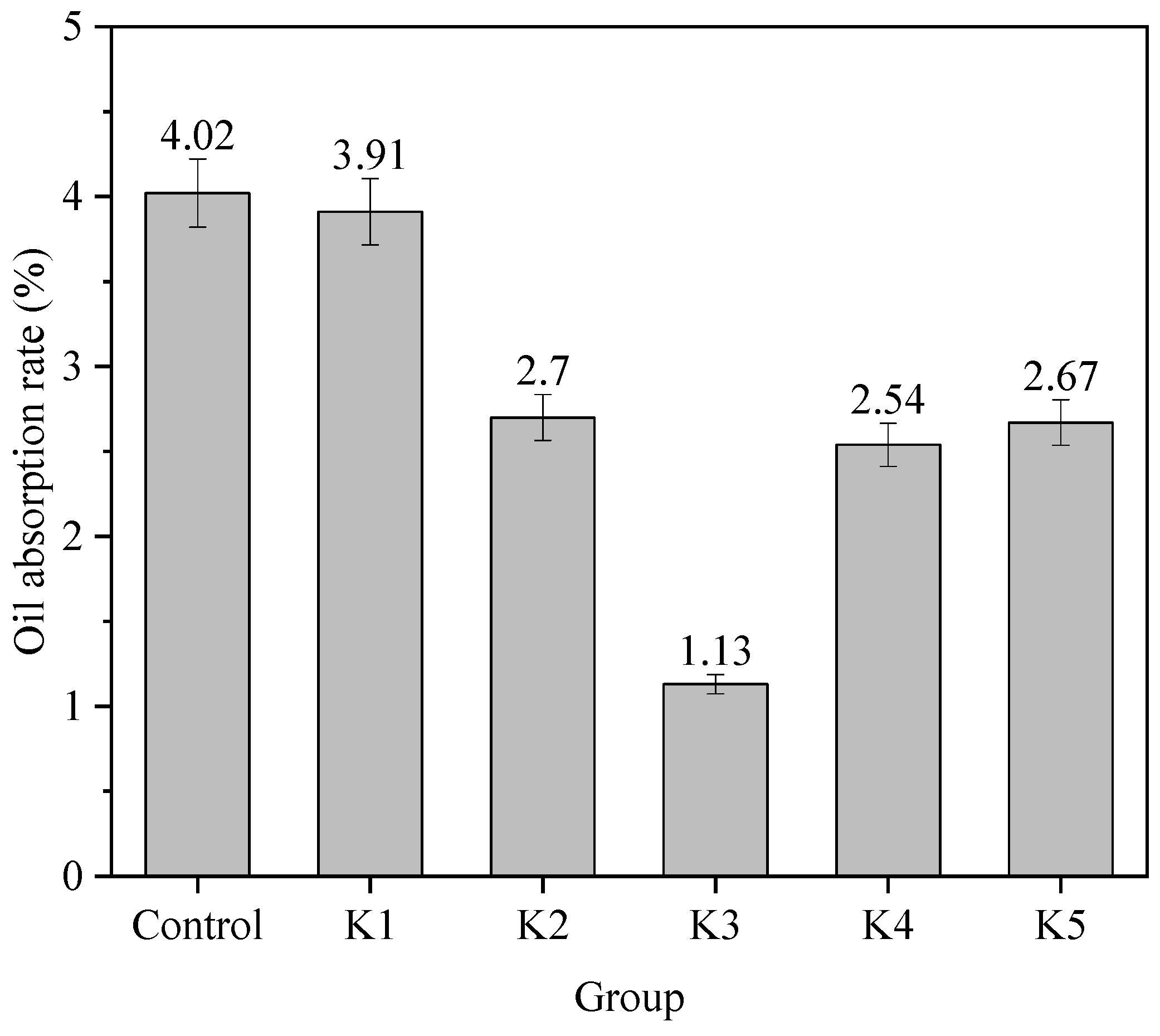

3.1. Effect of Nanoparticle Type on Resin Modification

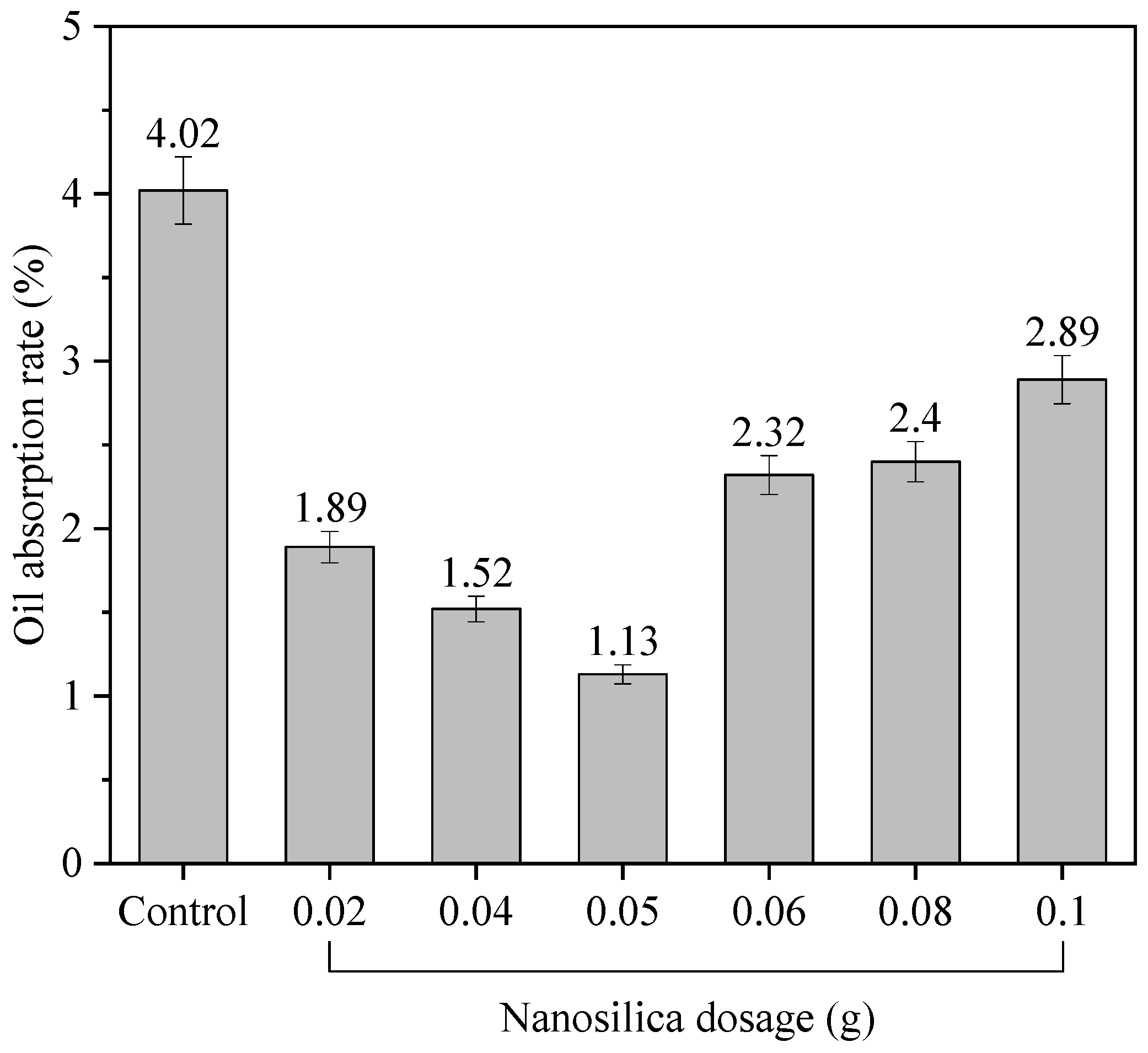

3.2. Effect of Nano-Silica Dosage on Resin Modification

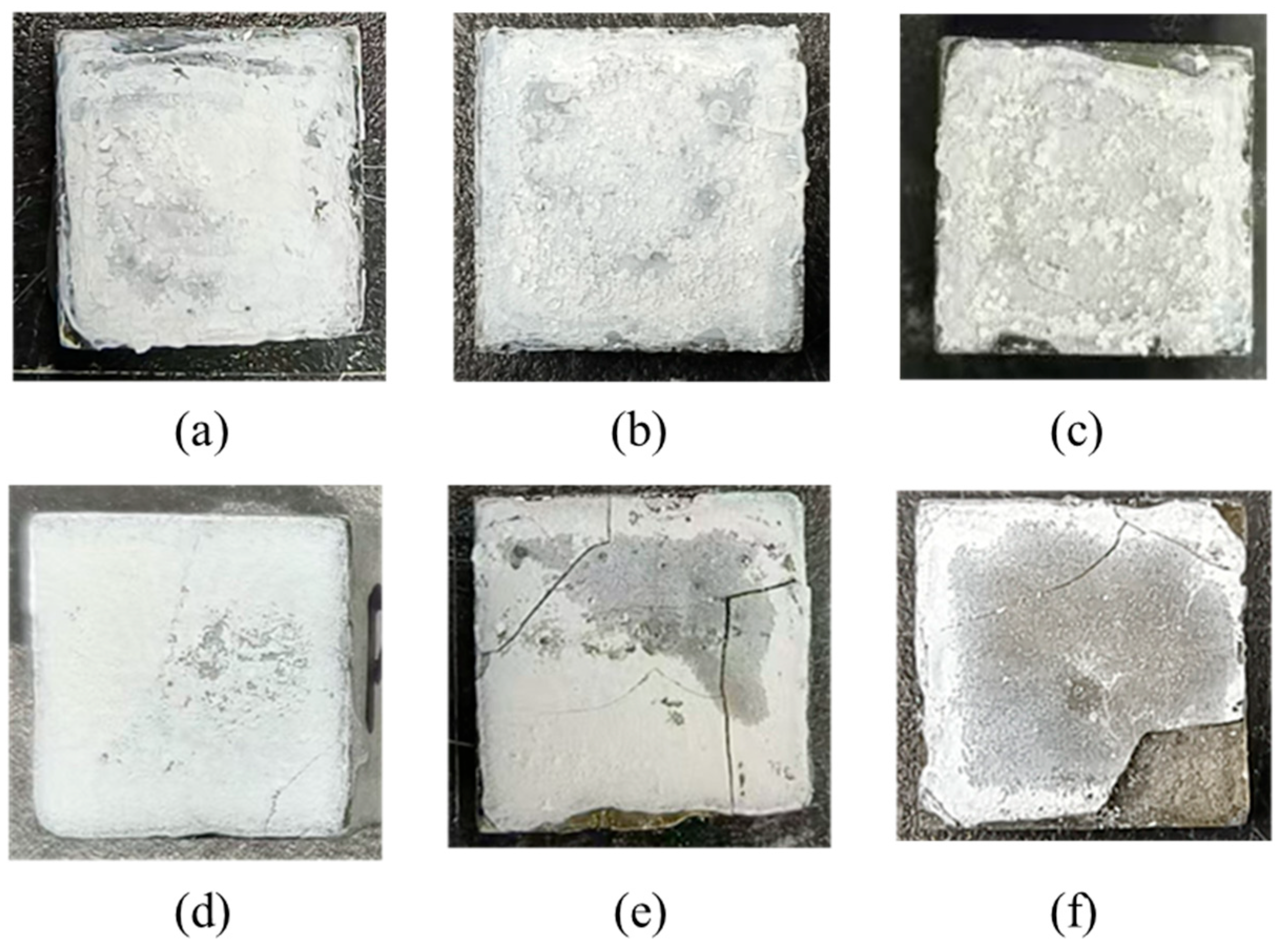

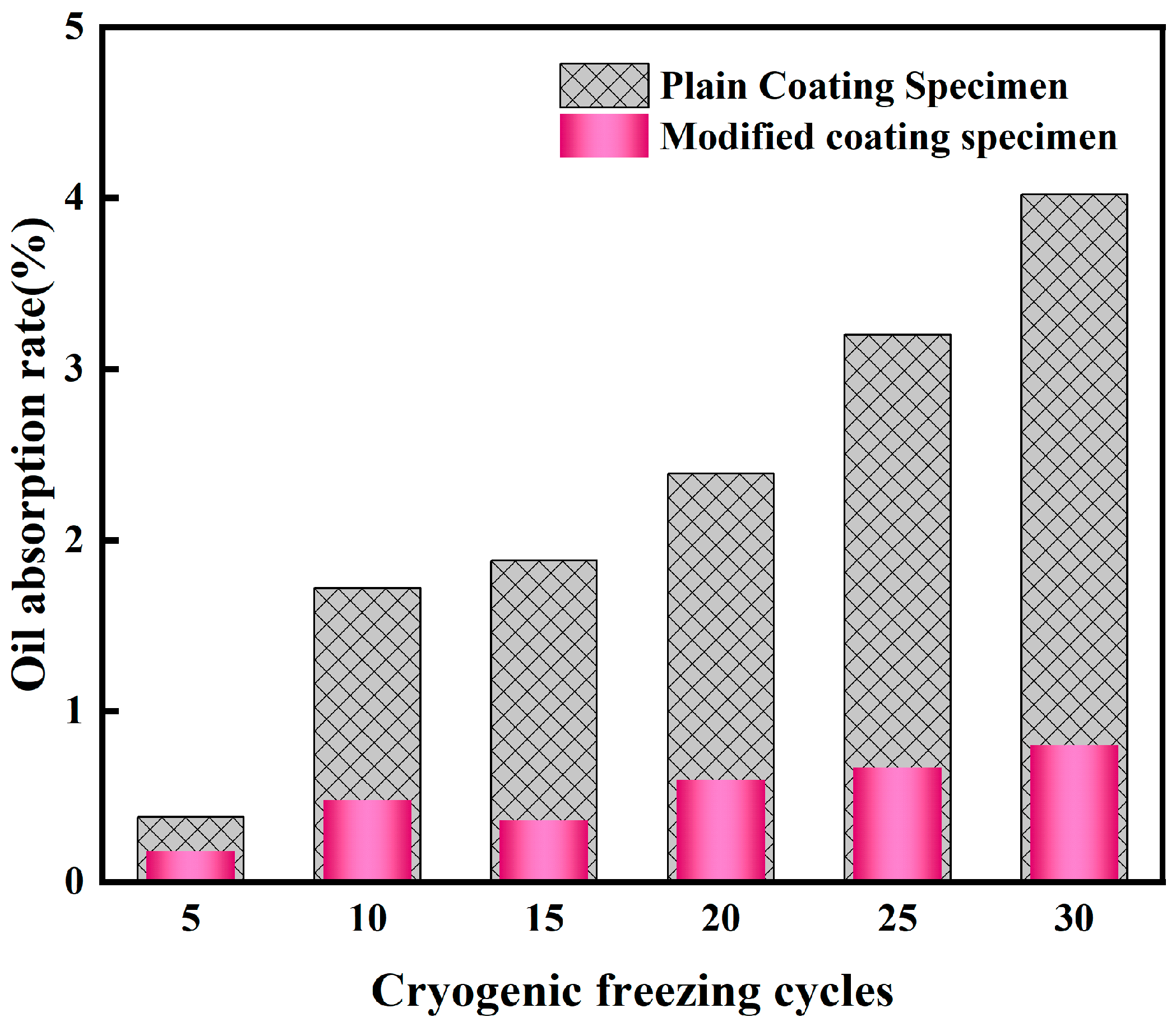

3.3. Appearance and Permeability of Coated Concrete After Cryogenic Freeze–Thaw Cycles

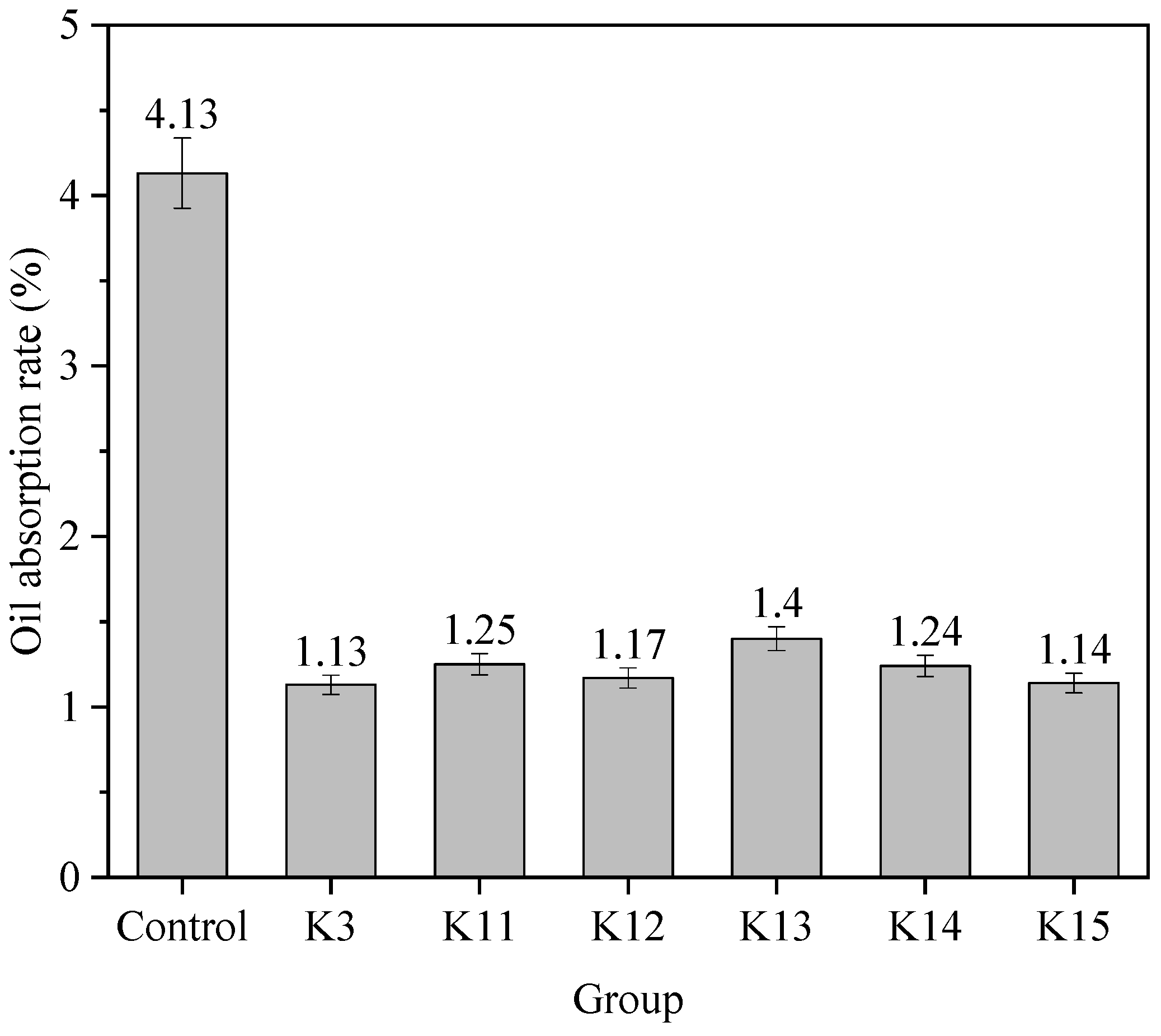

3.4. Mechanical Properties and Chemical Stability of Coated Concrete

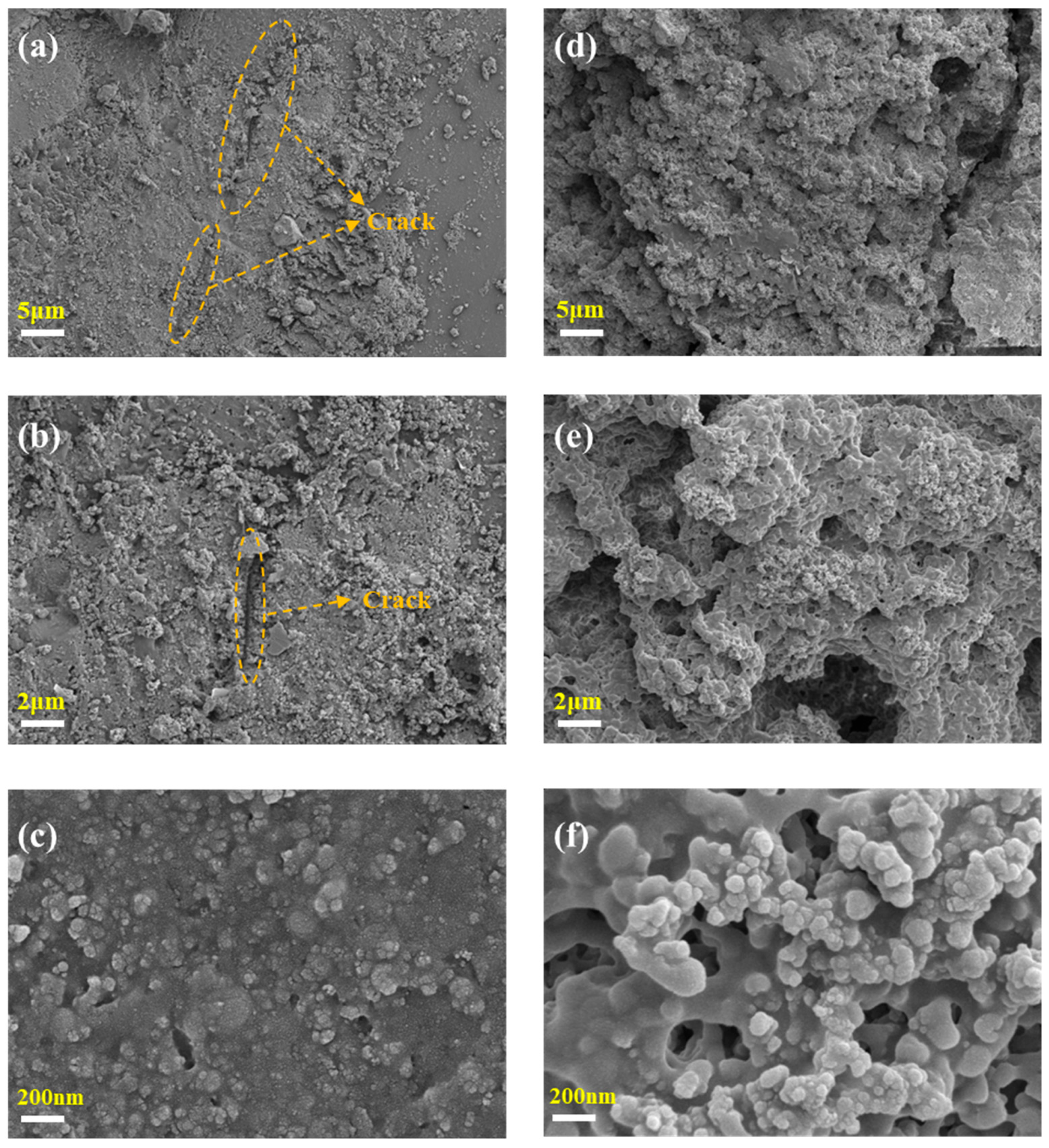

3.5. Microstructural Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, P.; Gu, K.; Jiang, Z. Preparation and Properties of Non-Autoclaved High-Strength Pile Concrete with Anhydrite and Ground Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhou, P.; Zhao, S.; Yang, Q.; Gu, K.; Song, Q.; Jiang, Z. Optimizing the Mixture Design of Manufactured Sand Concrete for Highway Guardrails in Mountainous Terrain. Buildings 2025, 15, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Tong, F.; Liu, G. An Effective Thermal Conductivity Model for Simulating the Heat Transfer Process of Concrete Dams under Extreme Temperature Conditions. Eng. Struct. 2025, 335, 120306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Li, Y. Effect of Waste Stone Powder on Compressive Strength and Pore Structure of Concrete in Extreme Low Temperature and Complex Environment. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, A.; Komar, A.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; Boyd, A.J. Global Assessment of Concrete Specimens Subjected to Freeze-Thaw Damage. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 133, 104716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, W. Microstructure and Damage Evolution of Hydraulic Concrete Exposed to Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 346, 128466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, F.; Wu, Y. Freeze–Thaw Deterioration Mechanisms of Concrete under Low-Temperature High-Frequency Cycling in High-Altitude Mountainous Regions. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, J.; Duan, P.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, D.; Wang, J. Mechanical Properties and Degradation Mechanism of LNG Containment Concrete Material under Cryogenic Conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogbara, R.B.; Iyengar, S.R.; Grasley, Z.C.; Rahman, S.; Masad, E.A.; Zollinger, D.G. Relating Damage Evolution of Concrete Cooled to Cryogenic Temperatures to Permeability. Cryogenics 2014, 64, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.H.; Han, Y.; Rhie, Y.H.; Won, N.I.; Na, Y.H. Spray Coating of Nanosilicate-Based Hydrogel on Concrete. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2201664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ding, Y.; Gao, T.; Qin, Y.; Lv, Y.; Wang, K. Chloride Resistance of Concrete Containing Nanoparticle-Modified Polymer Cementitious Coatings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299, 123736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.; Feng, P.; Ran, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Robust Water-Borne Multi-Layered Superhydrophobic Coating on Concrete with Ultra-Low Permeability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajir, K.; Toufigh, V.; Ghaemian, M. Protecting Ordinary Cement Concrete against Acidic and Alkaline Attacks Utilizing Epoxy Resin Coating. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 472, 141003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewei, D.; Xiaodong, W.; Ming, Z. Research Progress of Silane Impregnation and Its Effectiveness in Coastal Concrete Structures: A Review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Li, W.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Effect of Silicate Modulus on Tensile Properties and Microstructure of Waterproof Coating Based on Polymer and Sodium Silicate-Activated GGBS. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 252, 119056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Song, X.; He, X.; Su, Y.; Oh, S.K.; Chen, S.; Sun, Q. Durability Improvement Mechanism of Polymer Cement Protective Coating Based on Functionalized MXene Nanosheets Modified Polyacrylate Emulsion. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 186, 108021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y. Chloride Penetration of Surface-Coated Concrete: Review and Outlook. Materials 2024, 17, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Guo, K.; Wang, Y. Experimental Investigation on the Mechanical Properties of Waterborne Epoxy Resin Modified High-Performance Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Mater. Lett. 2025, 396, 138744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Zhou, P.; Li, S.; Cao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, Z.; Liu, A. Superior Corrosion Resistance of Mild Steel Coated with Graphene Oxide Modified Silane Coating in Chlorinated Simulated Concrete Solution. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 164, 106716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, M.R.; Bassuoni, M.T. Silane and Methyl-Methacrylate Based Nanocomposites as Coatings for Concrete Exposed to Salt Solutions and Cyclic Environments. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 115, 103841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talha, M.; Ma, Y.; Lin, Y. Improved In-Vitro Corrosion Performance of Resorbable Magnesium Alloy Using Distinctive Hybrid Silane Coatings with Modified Nano Graphene Oxide. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2026, 183, 115746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanasgaonkar, A.; Raja, V.S. Influence of Curing Temperature, Silica Nanoparticles- and Cerium on Surface Morphology and Corrosion Behaviour of Hybrid Silane Coatings on Mild Steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009, 203, 2260–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Guo, C.; Han, K.; Liu, F.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Qian, X.; Meng, J. Direct Recycling of Spent Graphite Anode via Calcium Silicate Coating for High-Capacity and Fast Lithium Storage. Carbon 2025, 244, 120727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio, J.; Silva, H.; Rodrigues, M.P.; Cabral-Fonseca, S.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Morais, F. Performance of a Polymeric Coating Material Applied to a Concrete Structure Affected by Internal Expansive Chemical Reactions. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 54, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, S.; Aminul Haque, M.; Chen, B. Water-Resistance Performance Analysis of Portland Composite Concrete Containing Waterproofing Liquid Membrane. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 106889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.X.; Luo, J.; Yan, W.J. Strength Deterioration Law and Microstructural Mechanism in Concrete Sprayed with Inorganic Coatings under the Freeze–Thaw Cycle. Res. Cold Arid Reg. 2025, 17, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, J.B.; Júnior, C. Carbonation of Surface Protected Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 49, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Feng, M.; Li, M.; Tian, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, G. Enhancing the Carbonation and Chloride Resistance of Concrete by Nano-Modified Eco-Friendly Water-Based Organic Coatings. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhao, L.; Xia, H.; Li, X.; Cui, L.; Niu, Y. Preparation and Properties of Octadecylamine Modified SiO2/Silicon-Acrylic Coating for Concrete Anti-Snowmelt Salt Corrosion. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 202, 109155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Liu, M.; Jiang, L. Recent Developments in Polymeric Superoleophobic Surfaces. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 2012, 50, 1209–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.R.; Salehi, M.; Eslami-Farsani, R. Fabrication and Investigation Superhydrophobic Micro/Nanoscaled Hierarchical Structure Coating on Brass with Evaluation of the Anti-Icing, Corrosion Resistance and Wetting Properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 709, 163807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, J.; Xu, P.; Chen, B. Robust and Transparent Superoleophobic Coatings from One-Step Spraying of SiO2@fluoroPOS. J. Solgel Sci. Technol. 2020, 93, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, X.; He, B.; Yang, Z.D.; Jiang, Z. Characterization and Stability of Innovative Modified Nanosilica-Resin Composite Coating: Subjected to Mechanical, Chemical, and Cryogenic Attack. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 197, 108780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM F 716-09; Standard Test Methods for Sorbent Performance of Absorbents. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009.

- Domun, N.; Hadavinia, H.; Zhang, T.; Sainsbury, T.; Liaghat, G.H.; Vahid, S. Improving the Fracture Toughness and the Strength of Epoxy Using Nanomaterials-a Review of the Current Status. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 10294–10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Li, X.F.; Bai, H.; Xu, W.W.; Yang, S.Y.; Lu, Y.; Han, J.J.; Wang, C.P.; Liu, X.J.; Li, W. Bin Influence of Microstructural Features on Thermal Expansion Coefficient in Graphene/Epoxy Composites. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.S.; Varischetti, J.; Lee, G.W.; Suhr, J. Experimental and Analytical Investigation of Mechanical Damping and CTE of Both SiO2 Particle and Carbon Nanofiber Reinforced Hybrid Epoxy Composites. Compos. Part. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurimoto, M.; Ozaki, H.; Sawada, T.; Kato, T.; Funabashi, T.; Suzuoki, Y. Filling Ratio Control of TiO2 and SiO2 in Epoxy Composites for Permittivity-Graded Insulator with Low Coefficient of Thermal Expansion. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2018, 25, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Miao, F.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jang, W.; Dames, C.; Lau, C.N. Controlled Ripple Texturing of Suspended Graphene and Ultrathin Graphite Membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Coating Composition | Nano-Particle | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Dosage (g) | ||

| Control | - | - | - |

| K1 | Surface layer and resin layer | - | - |

| K2 | Surface layer and bonding layer | - | - |

| K3 | Surface layer, bonding layer, and modified resin layer | Nano-SiO2 | 0.05 |

| K4 | Surface layer, bonding layer, and modified resin layer | Nano-TiO2 | 0.05 |

| K5 | Surface layer, bonding layer, and modified resin layer | Graphene | 0.05 |

| Group | Coating Composition | Nano-Particle | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Dosage (g) | ||

| Control | - | - | - |

| K6 | Surface layer, bonding layer, and modified resin layer | Nano-SiO2 | 0.02 |

| K7 | 0.04 | ||

| K3 | 0.05 | ||

| K8 | 0.06 | ||

| K9 | 0.08 | ||

| K10 | 0.10 | ||

| Group | Different Processing Methods |

|---|---|

| K11 | Sandpaper abrasion cycles: 100 times |

| K12 | Flaking caused by adhesive tape: 100 times |

| K13 | 1 mol/L HCl solution immersion: 24 h |

| K14 | 1 mol/L NaOH solution immersion: 24 h |

| K15 | 1 mol/L NaCl solution immersion: 24 h |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, P.; Zhao, S.; Gu, K.; Chen, H.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, Z. Preparation and Performance of Nano-Silica-Modified Epoxy Resin Composite Coating for Concrete Subjected to Cryogenic Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Coatings 2026, 16, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010019

Zhou P, Zhao S, Gu K, Chen H, Yang Q, Jiang Z. Preparation and Performance of Nano-Silica-Modified Epoxy Resin Composite Coating for Concrete Subjected to Cryogenic Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Pan, Sigui Zhao, Kang Gu, Hongji Chen, Qian Yang, and Zhengwu Jiang. 2026. "Preparation and Performance of Nano-Silica-Modified Epoxy Resin Composite Coating for Concrete Subjected to Cryogenic Freeze–Thaw Cycles" Coatings 16, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010019

APA StyleZhou, P., Zhao, S., Gu, K., Chen, H., Yang, Q., & Jiang, Z. (2026). Preparation and Performance of Nano-Silica-Modified Epoxy Resin Composite Coating for Concrete Subjected to Cryogenic Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Coatings, 16(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010019