Research on the BEM Reinforcement Mechanism of the POSF Method for Ocean Stone Construction

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Significance

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Research Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Object: POSF and CATC

- (1)

- Sampling point A faces the eastern sea directly. It is significantly affected by strong tidal scouring and sea breeze erosion. Barnacles here are easily stripped off by external forces [13], leading to a small number of attachments. So, it does not meet the sample collection requirements.

- (2)

- Sampling point B is located in the crevices of the revetment reefs. It is in a state of long-term seawater immersion, which is not conducive to the retention and accumulation of Crustacean Ash Triad Clay (CATC) materials [13]. The material reserves are relatively scarce.

- (3)

- Sampling point C, located on the embankment side with gentle tidal action and mild sea breeze impact, provided abundant CATC in stone crevices and was selected as the core sampling area (Figure 2).

2.2. Sample Processing

2.2.1. Processing of Chemical Analysis Samples (S-C-CATC)

- (1)

- Non-destructive testing: keep the original surface of the sample. Remove dust with a sterile soft brush for Raman testing [16].

- (2)

- Sample cutting: cut into 1 cm × 1 cm × 1 cm bean-sized test blocks for SEM-EDS and XRD testing, respectively.

- (3)

- XRD pretreatment: take particles from the core area of the sample. Grind them in an agate mortar and pass through a 200-mesh sieve. Add an internal standard substance (corundum). Dry at room temperature in a desiccator for 24 h, and prepare the sample on a glass slide [17].

2.2.2. Processing of S-M-CATC

- (1)

- FTIR sample pretreatment: in a dry environment, take visible samples and an appropriate amount of dry potassium bromide powder (ratio about 1:100) into a mortar. Grind thoroughly multiple times, then place in a tablet press to form transparent thin slices for functional group testing.

- (2)

- 16S rRNA sample pretreatment: use a sterile knife to scrape CATC from the barnacle attachment area (about 0.5 g). Quickly transfer to a sterile packaging bag. Store in an ultra-low-temperature refrigerator at −80 °C within 45 min to avoid microbial nucleic acid degradation and ensure the accuracy of subsequent high-throughput sequencing.

2.3. Experimental Methods

2.3.1. XRD Analysis

2.3.2. Raman Analysis

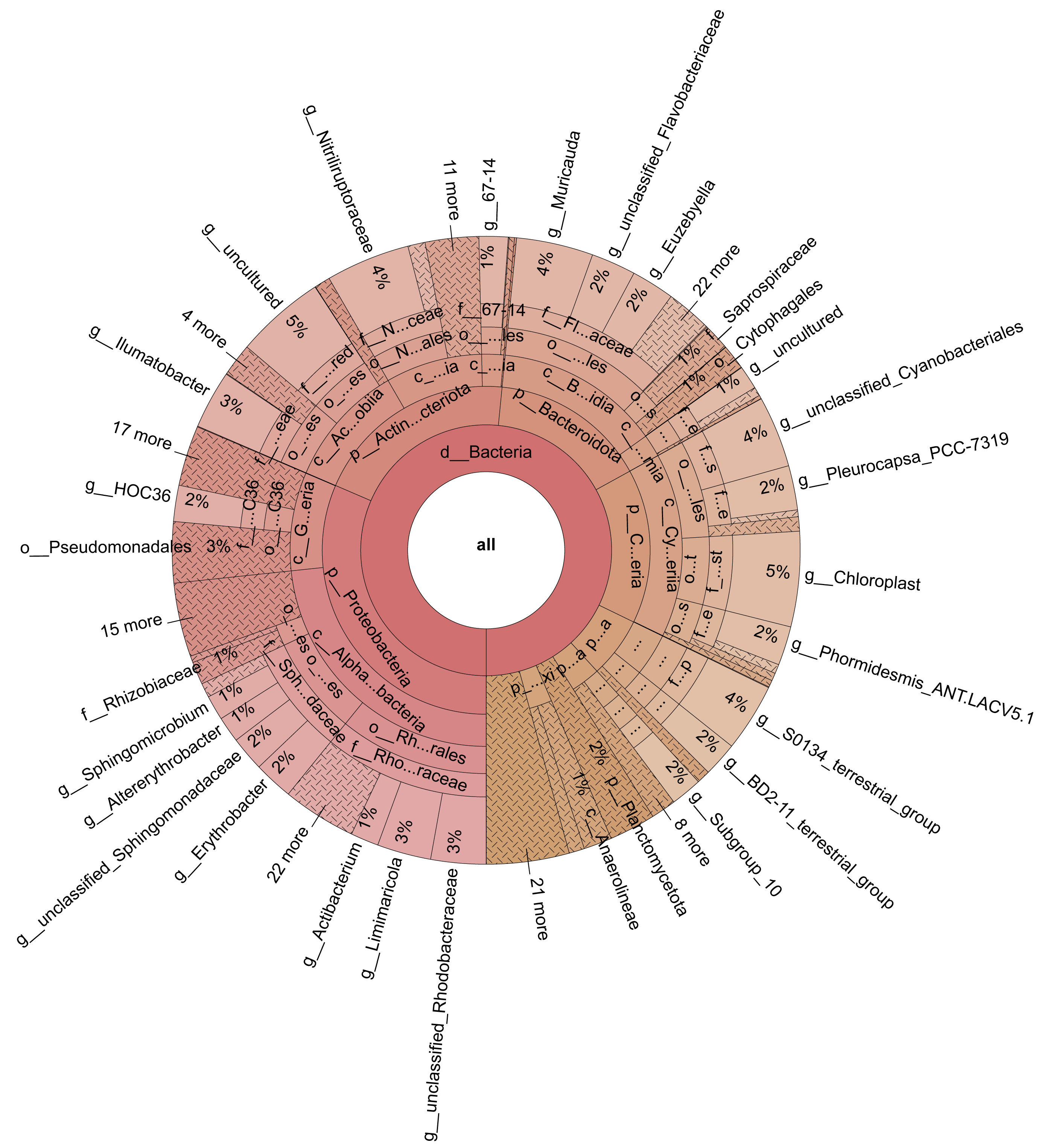

2.3.3. SEM Analysis

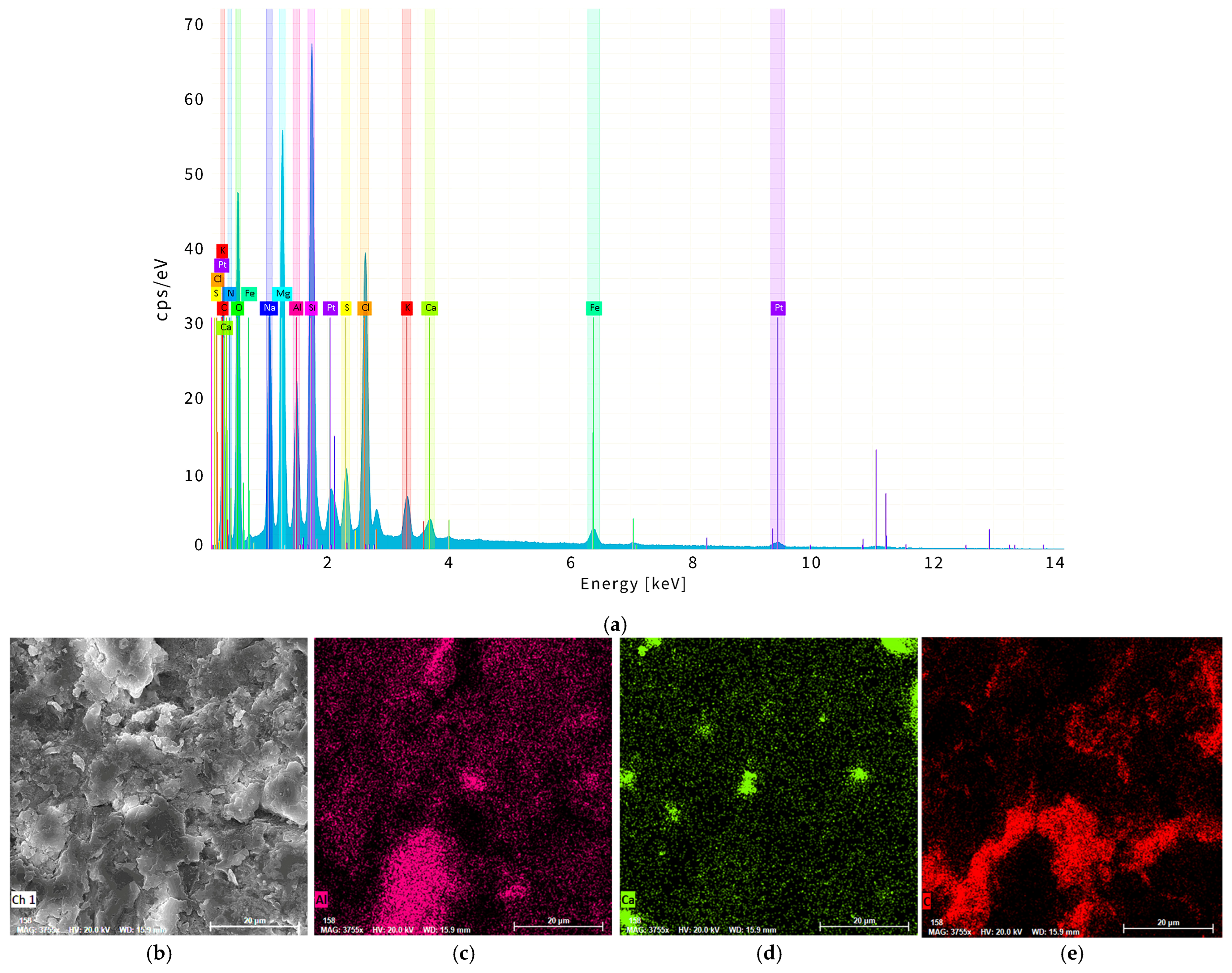

2.3.4. EDS Analysis

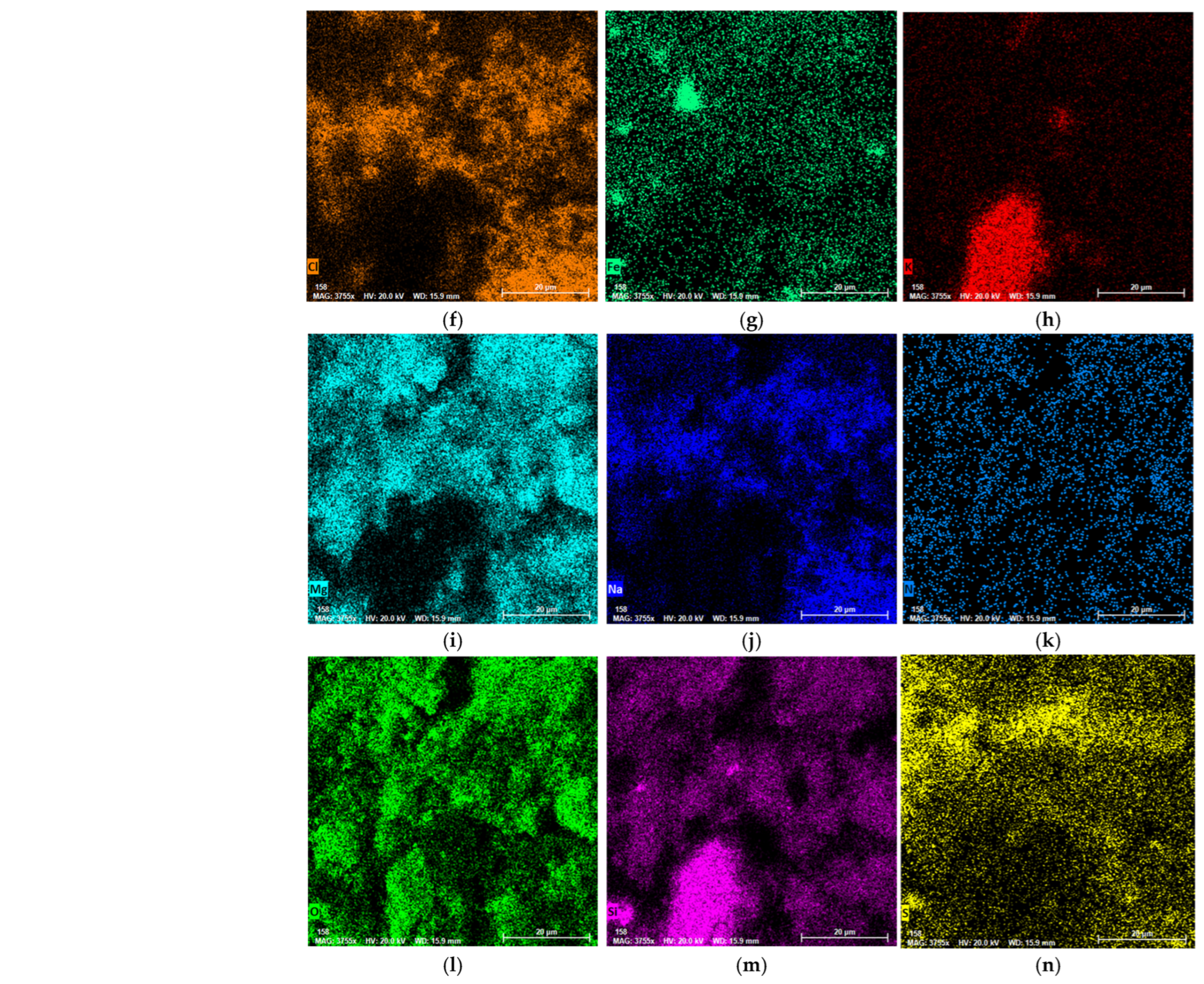

2.3.5. FTIR Functional Group Detection

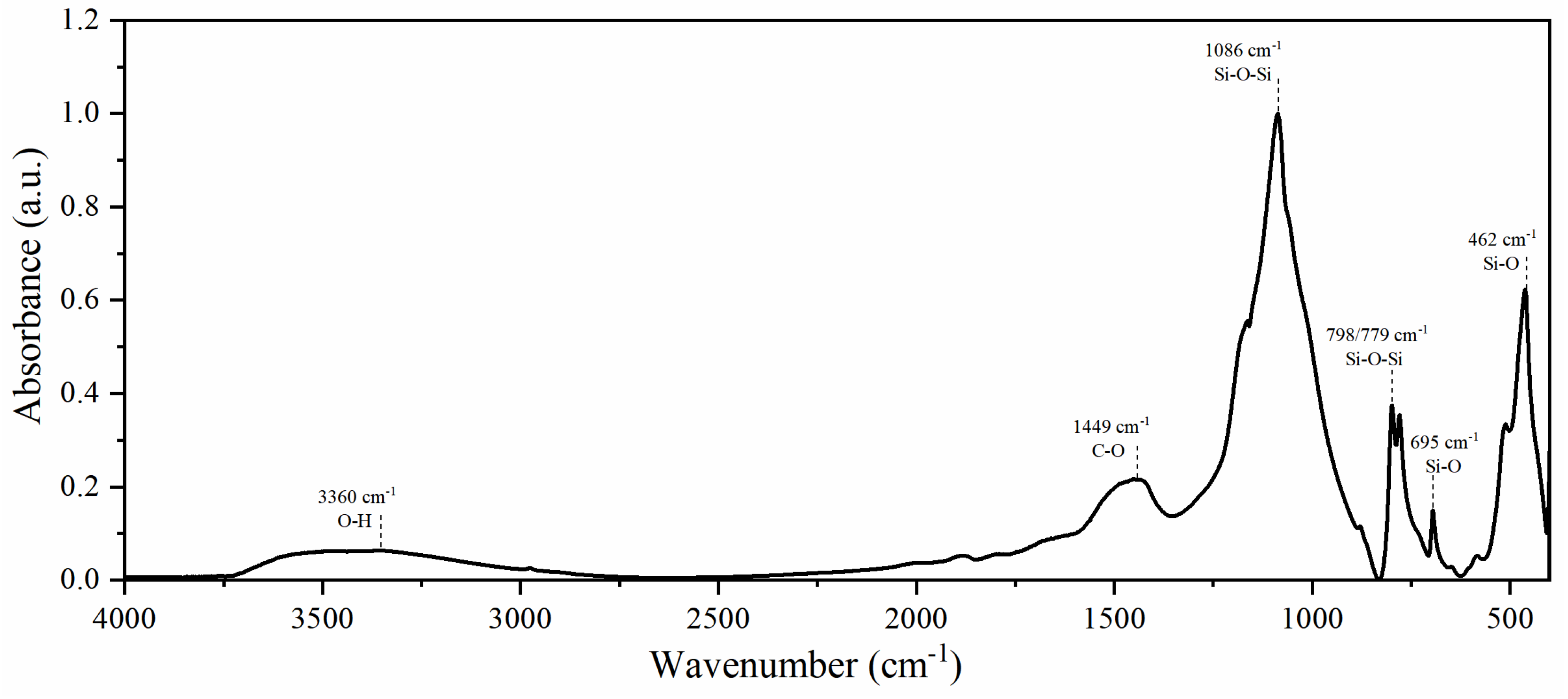

2.3.6. The 16S rRNA Sequencing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Combined XRD and Raman Analysis: Material Composition Characteristics

3.2. SEM-EDS Analysis: Element Distribution and Pore Characteristics

3.3. FTIR Analysis: Physical Reinforcement Mechanism

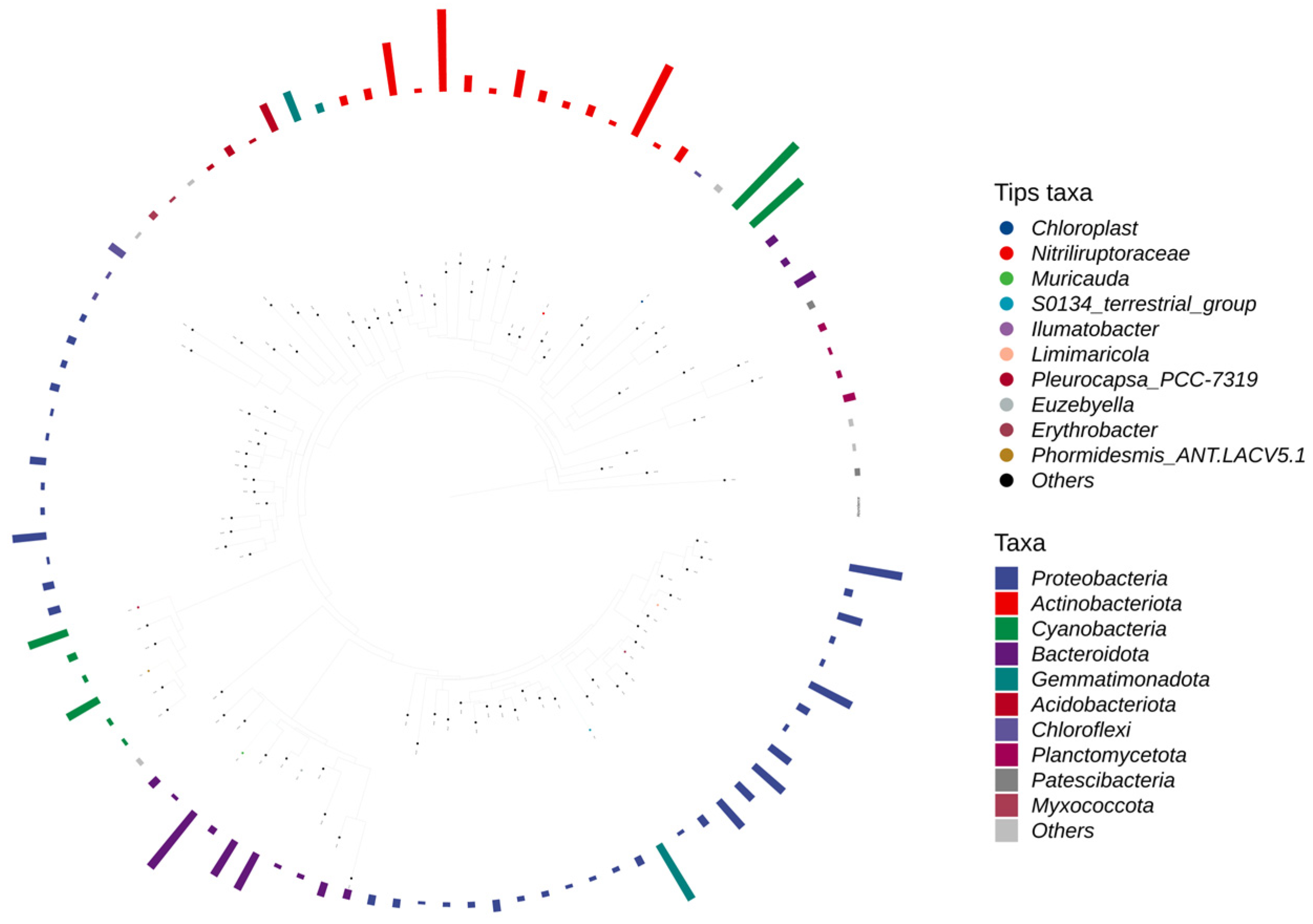

3.4. The 16S rRNA Analysis: Chemical Reinforcement Mechanism

4. Conclusions

5. Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CATC | Crust Ash Triad Clay |

| POSF | Planting oysters to strengthen the foundation |

| BEM | Biology–Environment–Materials |

Appendix A

| No. | Element | Pore Area | Non-Porous Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C | 20.95 | 38.49 |

| 2 | N | 1.80 | 2.83 |

| 3 | O | 39.00 | 29.73 |

| 4 | Na | 3.11 | 4.09 |

| 5 | Mg | 6.90 | 5.84 |

| 6 | Al | 1.21 | 2.04 |

| 7 | Si | 9.23 | 5.69 |

| 8 | S | 0.28 | 1.01 |

| 9 | Cl | 4.61 | 5.55 |

| 10 | K | 0.13 | 1.21 |

| 11 | Ca | 10.51 | 0.65 |

| 12 | Fe | 1.54 | 1.23 |

| 13 | Zr | 0.48 | - |

| 14 | Pt | 2.81 | 2.88 |

| Total | 102.57 | 101.26 |

| No. | Species | Abundance | Metabolic Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nitriliruptoraceae | 0.042 | Heterotrophic |

| 2 | Muricauda | 0.039 | Heterotrophic |

| 3 | Cyanobacteriales | 0.036 | Photosynthetic aerobic |

| 4 | S0134_terrestrial_group | 0.034 | Heterotrophic |

| 5 | Limimaricola | 0.026 | Photosynthetic aerobic |

| 6 | Euzebyella | 0.022 | Heterotrophic |

| 7 | Pleurocapsa PCC-7319 | 0.021 | Photosynthetic aerobic |

| 8 | Ilumatobacter | 0.021 | microaerophilic |

| 9 | Phormidesmis ANT.LACV5.1 | 0.020 | Photosynthetic aerobic |

| 10 | Erythrobacter | 0.011 | Heterotrophic |

References

- Ez-zaki, H.; El Gharbi, B.; Diouri, A. Development of eco-friendly mortars incorporating glass and shell powders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 159, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, E.; Terroso, D.; Sequeira, M.C.; Azevedo, M.C.; Coroado, J. A Starting Point on Recycling Land and Sea Snail Shell Wastes to Manufacture Quicklime, Milk of Lime, and Hydrated Lime. Materials 2024, 17, 5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, E.; Feathers, J.K. Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Radiocarbon Dating of Temper in Shell-Tempered Ceramics: Test Cases from Mississippi, Southeastern United States. Am. Antiq. 2009, 74, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.S. Luoyang Bridge, one of the “Four Great” famous bridges in ancient China, is renowned worldwide for its unique “oyster planting and foundation fixing method” on the Song stele of Cai Xiang’s “Record of Wan’an Bridge”. Chin. Place Names 2012, 7, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Shi, W.J.; Li, N.N.; Fan, R.L.; Zhang, W.K.; Qi, W.M. Oyster and barnacle recruitment dynamics on and near a natural reef in China: Implications for oyster reef restoration. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 905373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidour, K.; Al, H.N.; Crassard, R.; D’sIlva, F.; Al Haj, A. Exploring the Early Neolithic in the Arabian Gulf: A newly discovered 8,400–year-old stone-built architecture on Ghagha Island, United Arab Emirates. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhai, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, K. Barnacle attachment and its corrosion effects on the surface of the Yangtze Estuary II Shipwreck. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 67, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.D.; Fan, J.H.; Li, R.N.; Da, B.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y. Influence of the Usage of Waste Oyster Shell Powder on Mechanical Properties and Durability of Mortar. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.N.; Gu, X.W.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.P.; Nehdi, M.L.; Zhang, Y.N. Study on the Mechanism of Early Strength Strengthening and Hydration of LC3 Raised by Shell Powder. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.H.; Shen, M.L.; Shi, J.Y.; Yalçınkaya, Ç.; Du, S.G.; Yuan, Q. Recycling Coral Waste into Eco-Friendly UHPC: Mechanical Strength, Microstructure, and Environmental Benefits. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 836, 155424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Zhan, J.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; He, Z.H.; Xie, Y.D. Low-Carbon UHPC with Glass Powder and Shell Powder: Deformation, Compressive Strength, Microstructure and Ecological Evaluation. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 109833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.; Antas, P.; Castro, L.F.C.; Campos, A.; Vasconcelos, V. Comparative analysis of the adhesive proteins of the adult stalked goose barnacle Pollicipes pollicipes (Cirripedia: Pedunculata). Mar. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofia, C.F.; Aldred, N.; Sykes, A.V.; Cruz, T.; Clare, A.S. The effects of rearing temperature on reproductive conditioning of stalked barnacles (Pollicipes pollicipes). Aquaculture 2015, 448, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rilwan, U.; Abdulazeez, M.A.; Maina, I.; Olasoji, O.W.; El-Taher, A. The Use of Coconut Shell Ash as Partial Replacement of Cement to Improve the Thermal Properties of Concrete and Waste Management Sustainability in Nigeria and Africa, for Radiation Shielding Application. Sci. Afr. 2025, 27, e02578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.; Selvaraj, T. Production of Lime Finishes Using Fermented Opuntia Ficus Indica Extract: A Sustainable and Multifunctional Binder for Indian Lime-Built Heritage Structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 142965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zheng, R. Research on the Composition and Casting Technology of Bronze Arrowheads Unearthed from the Ruins of the Imperial City of the Minyue Kingdom. Materials 2025, 18, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.H.; Guan, R.M.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.X. Durability analysis of brick-faced clay-core walls in traditional residential architecture in quanzhou, china. Coatings 2025, 15, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meryem, B.; Alan, M.; Bin, C. Raman Match: Application for automated identification of minerals from Raman spectroscopy data. Am. Mineral. 2025, 110, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbrock, R.; Stein, M.; Schaller, J. Comparing amorphous silica, short-range-ordered silicates and silicic acid species by FTIR. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoal, F.; Duarte, P.; Assmy, P.; Costa, R.; Magalhães, C. Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing combined with adequate database selection improves the description of arctic marine prokaryotic communities. Ann. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.C.; Lu, C.L.; Dong, Y.W.; Chen, J.W.; Chiang, Y.T. Research on Innovative Green Building Materials from Waste Oyster Shells into Foamed Heat-Insulating Bricks. Clean. Mater. 2024, 11, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.Y.; Alsuwaidi, M.; Antler, G.; Zhao, G.B.; Morad, S. Depositional control on composition, texture and diagenesis of modern carbonate sediments: A comparative study of tidal channels and marshes, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Sediment. Geol. 2024, 472, 106744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, R.; Dou, M.X.; Bai, Y.; Yue, Z.C.; Sun, Q.Y.; Yin, W.Z. Study of the difference in floatability between quartz and feldspar based on first principles. Chem. Phys. 2025, 592, 112612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retko, K.; Legan, L.; Kosel, J. Identification of iron gall inks, logwood inks, and their mixtures using Raman spectroscopy, supplemented by reflection and transmission infrared spectroscopy. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, G.; Galasso, C.; Palma, E.F.; Esposito, F.P.; Piccionello, A.P.; Villanova, V. Mixotrophy in Marine Microalgae to Enhance Their Bioactivity. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.F.; Cong, G.W.; Ni, S.Y.; Sun, J.Q.; Guo, C.; Chen, M.X.; Quan, H.Z. Recycling of Waste Oyster Shell and Recycled Aggregate in the Porous Ecological Concrete Used for Artificial Reefs. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikkam, R.; Kaari, M.; Baskaran, A.; Ramakodi, M.P.; Venugopal, G.; Bhaskar, P.V. Existence of rare actinobacterial forms in the Indian sector of Southern Ocean: 16 S rRNA based metabarcoding study. Braz J Microbiol. 2024, 55, 2363–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.Z.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhao, H.T.; Xia, Y.; Su, Y.L.; Wang, H.G.; Wang, L. Algae-bacteria symbiosis for cracks active repair in cement mortar: A novel strategy to enhance microbial self-healing efficacy. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 483, 141815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.H.; Park, S.M.; Yang, B.J.; Jang, J.G. Calcined Oyster Shell Powder as an Expansive Additive in Cement Mortar. Materials 2019, 12, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanzadeh, F.; Emam-Jomeh, M.; Edalat-Behbahani, A.; Soltan-Zadeh, Z. Development and Characterization of Blended Cements Containing Seashell Powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 161, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.H.; Zhai, X.F.; Yang, J.; Pei, Y.Y.; Guan, F.; Chen, Y.D.; Duan, J.Z.; Hou, B.R. Desulfovibrio-induced gauzy FeS for efficient hexavalent chromium removal: The influence of SRB metabolism regulated by carbon source and electron carriers. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 674, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrivener, K.L.; John, V.M.; Gartner, E.M. Eco-Efficient Cements: Potential Economically Viable Solutions for a Low-CO2 Cement-Based Materials Industry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Mineral | Chemical Formula | Mass |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quartz | SiO2 | 94.6 |

| 2 | Potassium feldspar | KAlSi3O8 | 4.3 |

| 3 | Dolomite | CaMg(CO3)2 | 1.1 |

| Total | 100 | ||

| No. | Chemical Compound | Chemical Formula | Main Characteristic Peaks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quartz | SiO2 | 128.0, 207.1, 467.4 |

| 2 | Potassium feldspar | KAlSi3O8 | 154.3, 279.6, 511.0 |

| 3 | Dolomite | CaMg (CO3)2 | 297.9, 1094.3, 1325.7 |

| 4 | Chalcopyrite | CuFeS2 | 293.1, 410.8, 611.3 |

| 5 | Hematite | Fe2O3 | 151.3, 288.2 |

| Sampling Area | Gray Value | Mean Gray Value | Percentage of Pore Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 139,369 | 83.354 | 19.56 |

| 2 | 122,771 | 66.571 | 17.30 |

| 3 | 144,605 | 64.726 | 20.28 |

| Mean porosity | 19.04 | ||

| No. | Chemical Functional Groups | Main Characteristic Peaks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | O-H | 3360 |

| 2 | C-O | 1449 |

| 3 | Si-O-Si | 1086 |

| 4 | Si-O-Si | 798, 779 |

| 5 | Si-O | 695 |

| 6 | Si-O | 462 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ding, Y.; Lai, Y.; Wang, J.; Fu, Y.; Chen, L.; Ma, T.; Guan, R. Research on the BEM Reinforcement Mechanism of the POSF Method for Ocean Stone Construction. Coatings 2026, 16, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010145

Ding Y, Lai Y, Wang J, Fu Y, Chen L, Ma T, Guan R. Research on the BEM Reinforcement Mechanism of the POSF Method for Ocean Stone Construction. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Yuhong, Yujing Lai, Jinxuan Wang, Yili Fu, Li Chen, Tengfei Ma, and Ruiming Guan. 2026. "Research on the BEM Reinforcement Mechanism of the POSF Method for Ocean Stone Construction" Coatings 16, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010145

APA StyleDing, Y., Lai, Y., Wang, J., Fu, Y., Chen, L., Ma, T., & Guan, R. (2026). Research on the BEM Reinforcement Mechanism of the POSF Method for Ocean Stone Construction. Coatings, 16(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010145