Influence of Nano-Sized Ceramic Reinforcement Content on the Powder Characteristics and the Mechanical, Tribological, and Corrosion Properties of Al-Based Alloy Nanocomposites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Fabrication Process

2.3. Particle Microhardness and Particle Size

2.4. X-Ray Diffraction

2.5. Morphological Characterization

2.6. Hardness and Tensile Test

2.7. Wear Test

2.8. Corrosion Test

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Powder Characterization

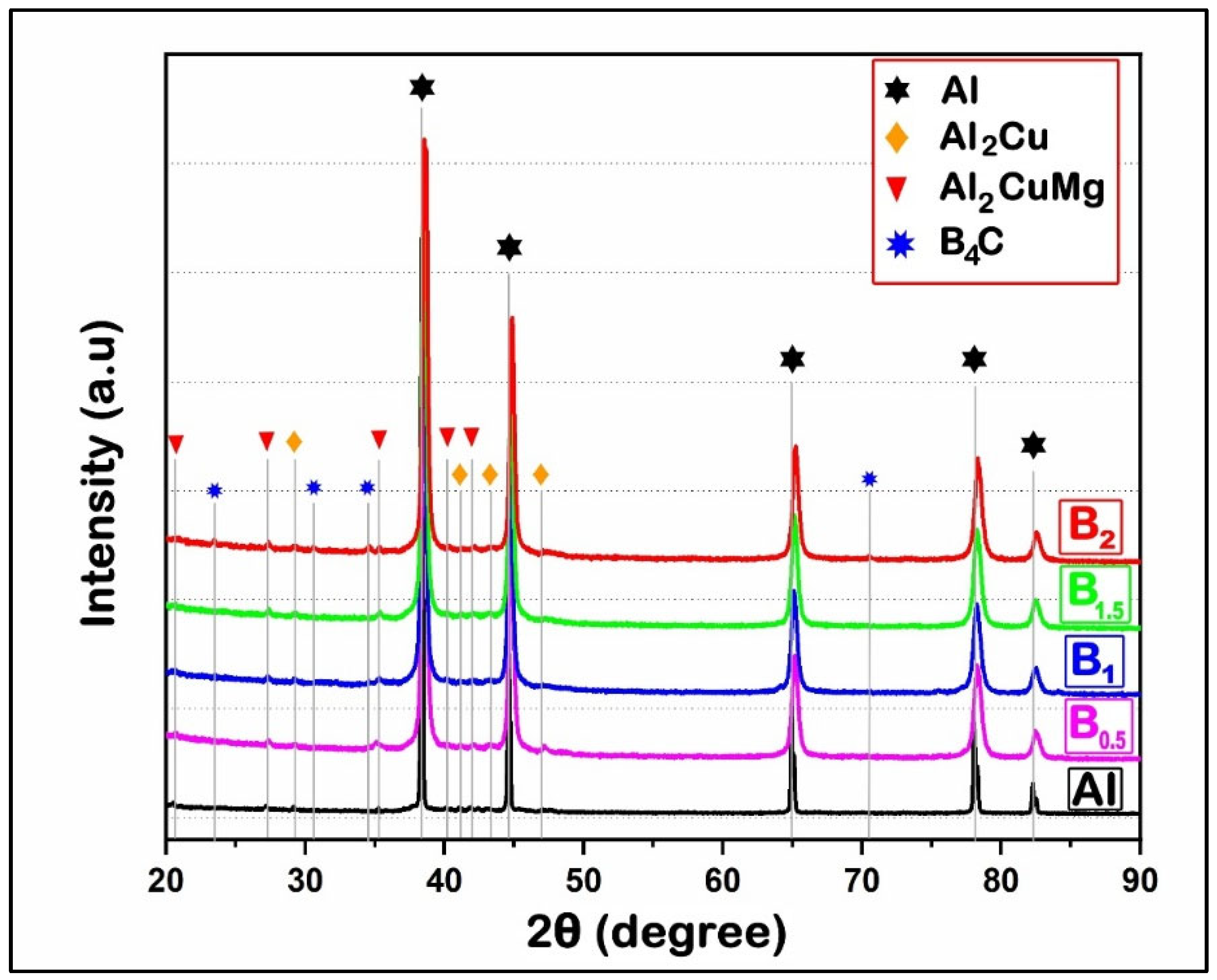

3.2. XRD Analysis

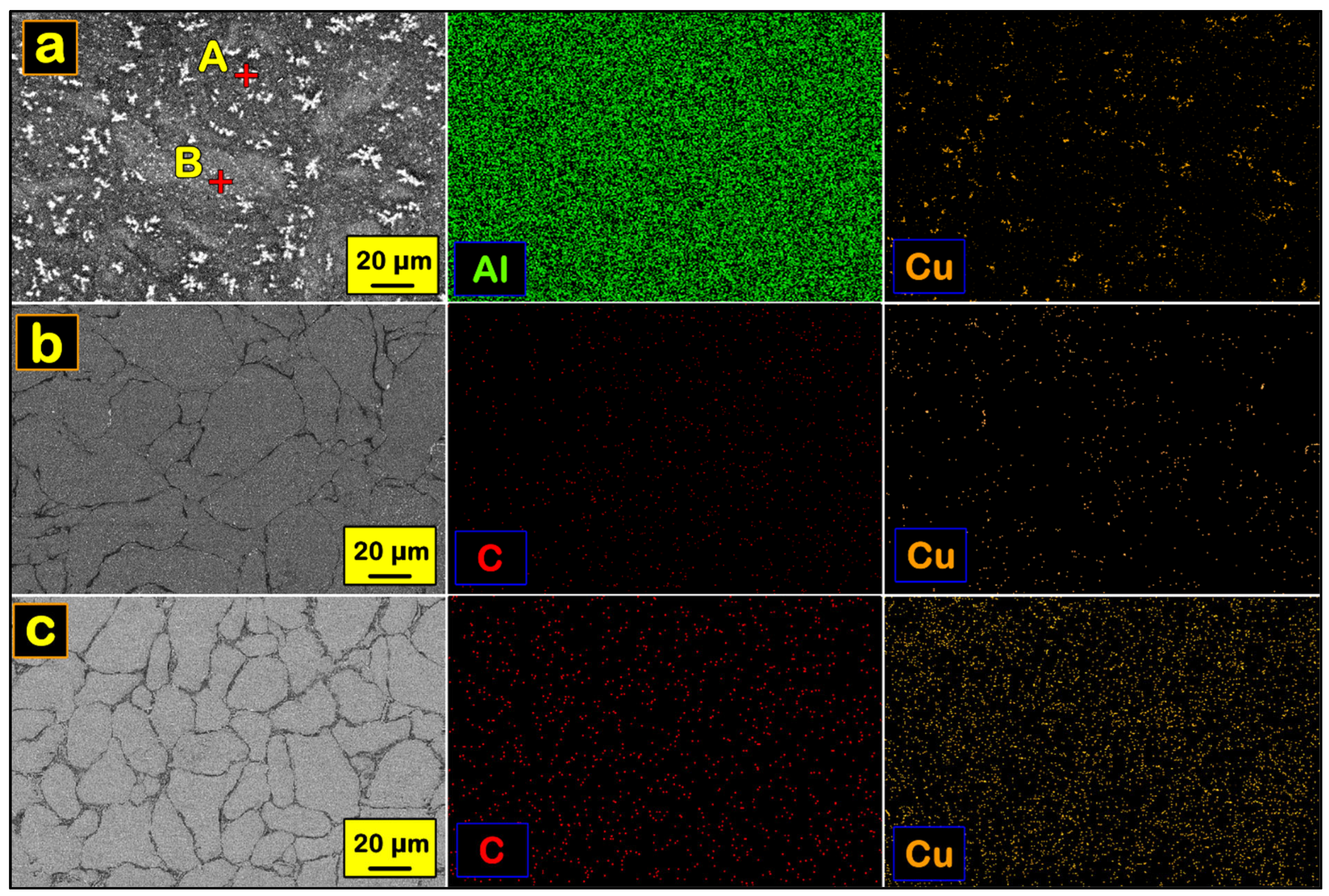

3.3. Microstructural Characterization

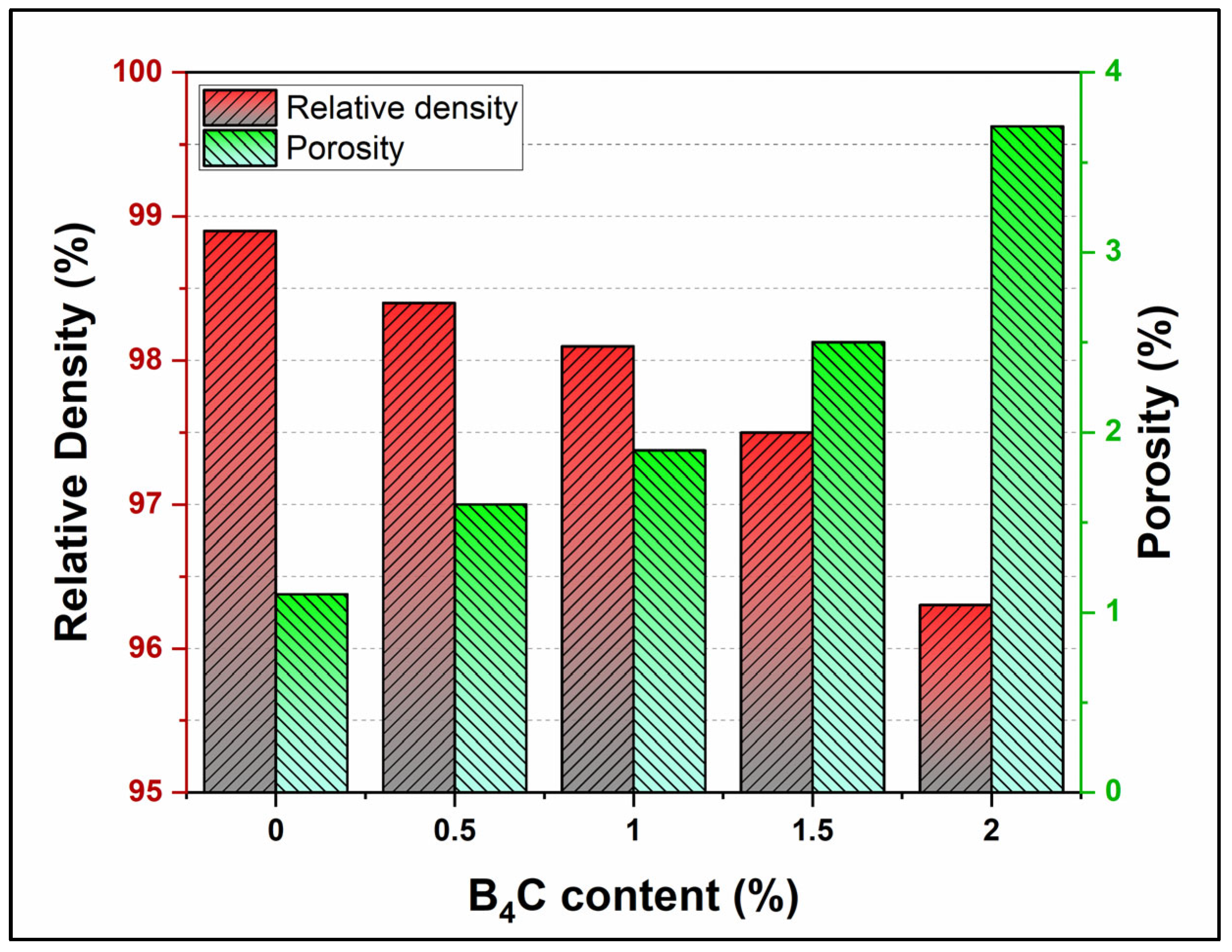

3.4. Relative Density

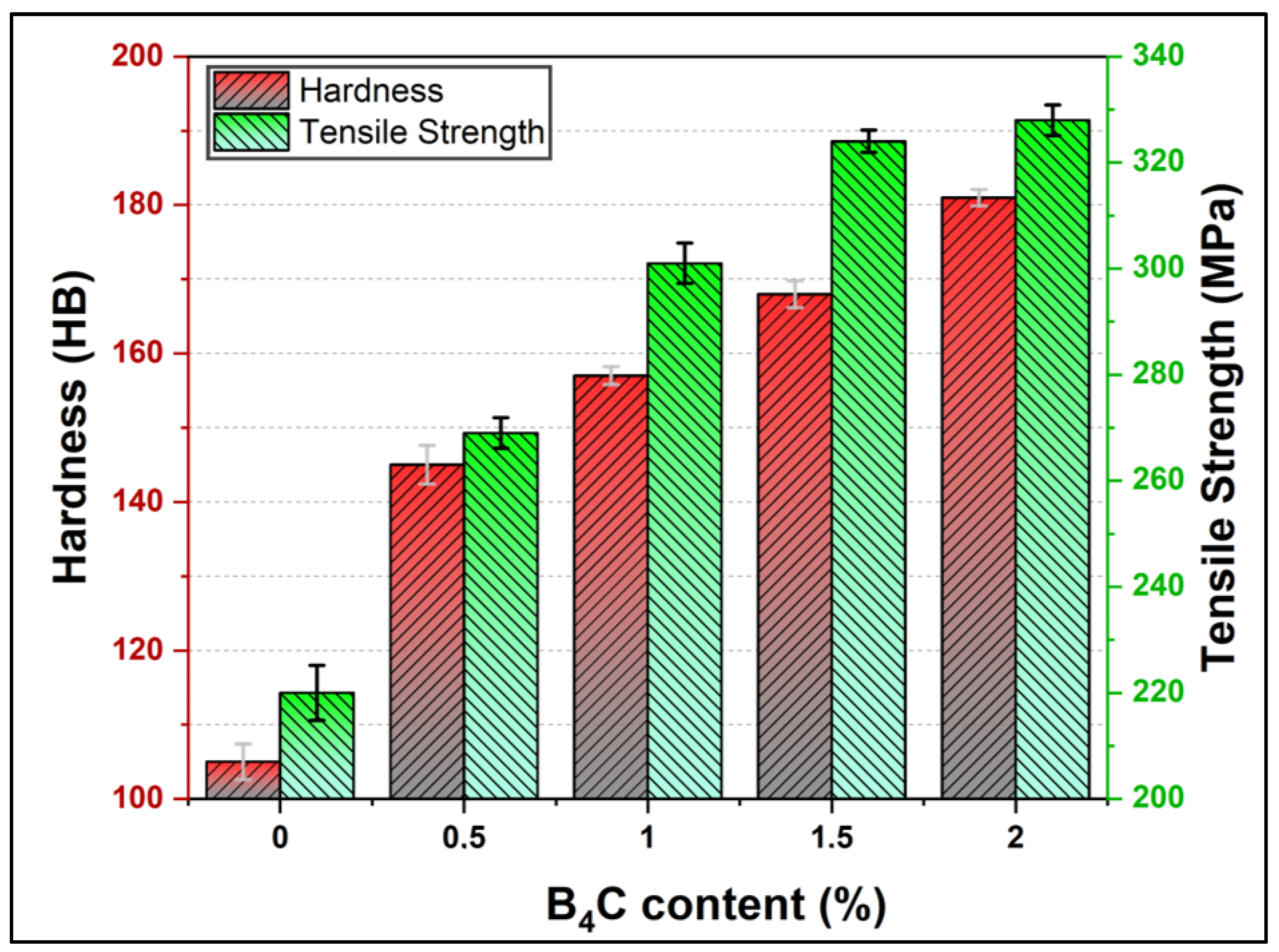

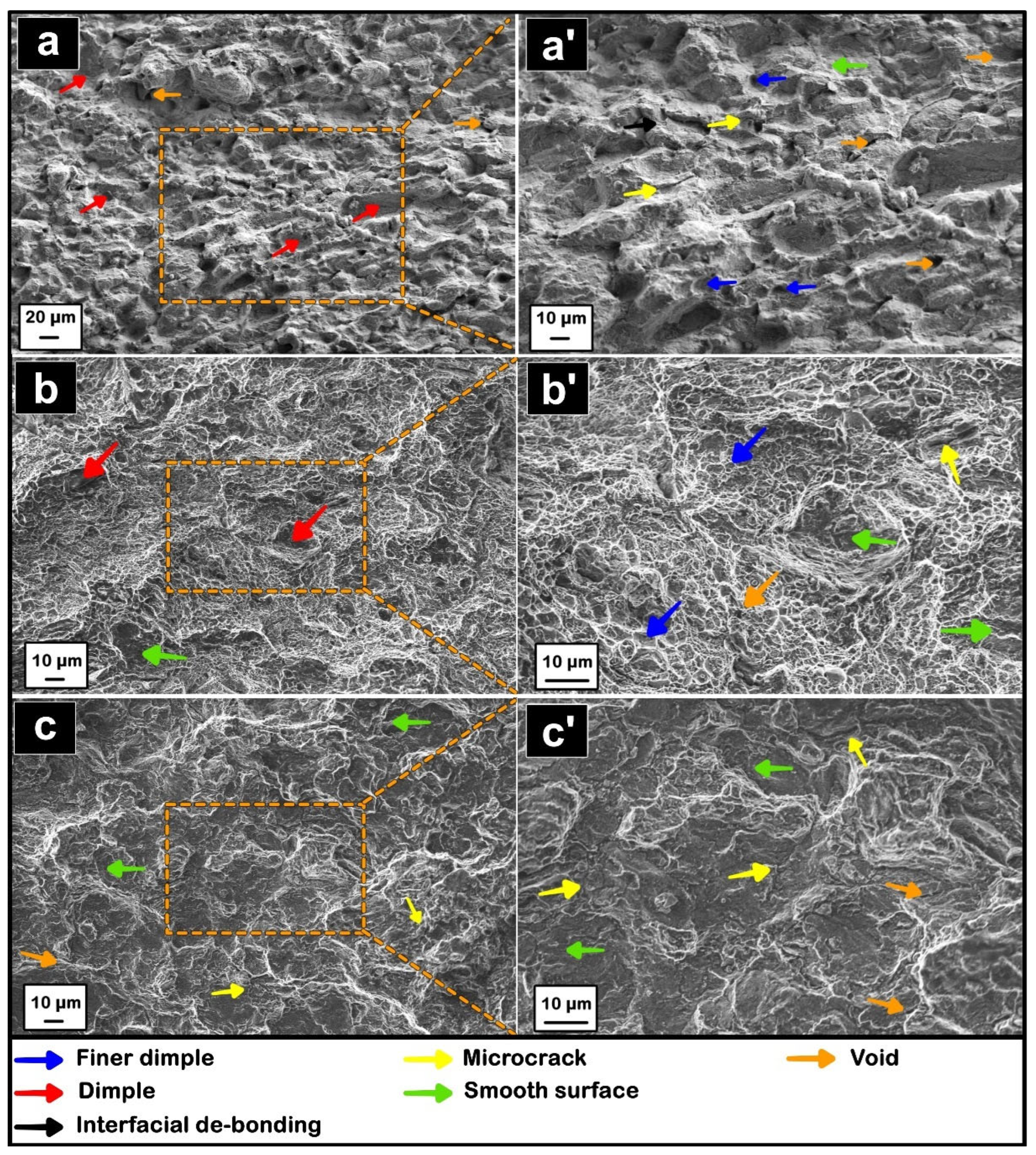

3.5. Mechanical Behavior

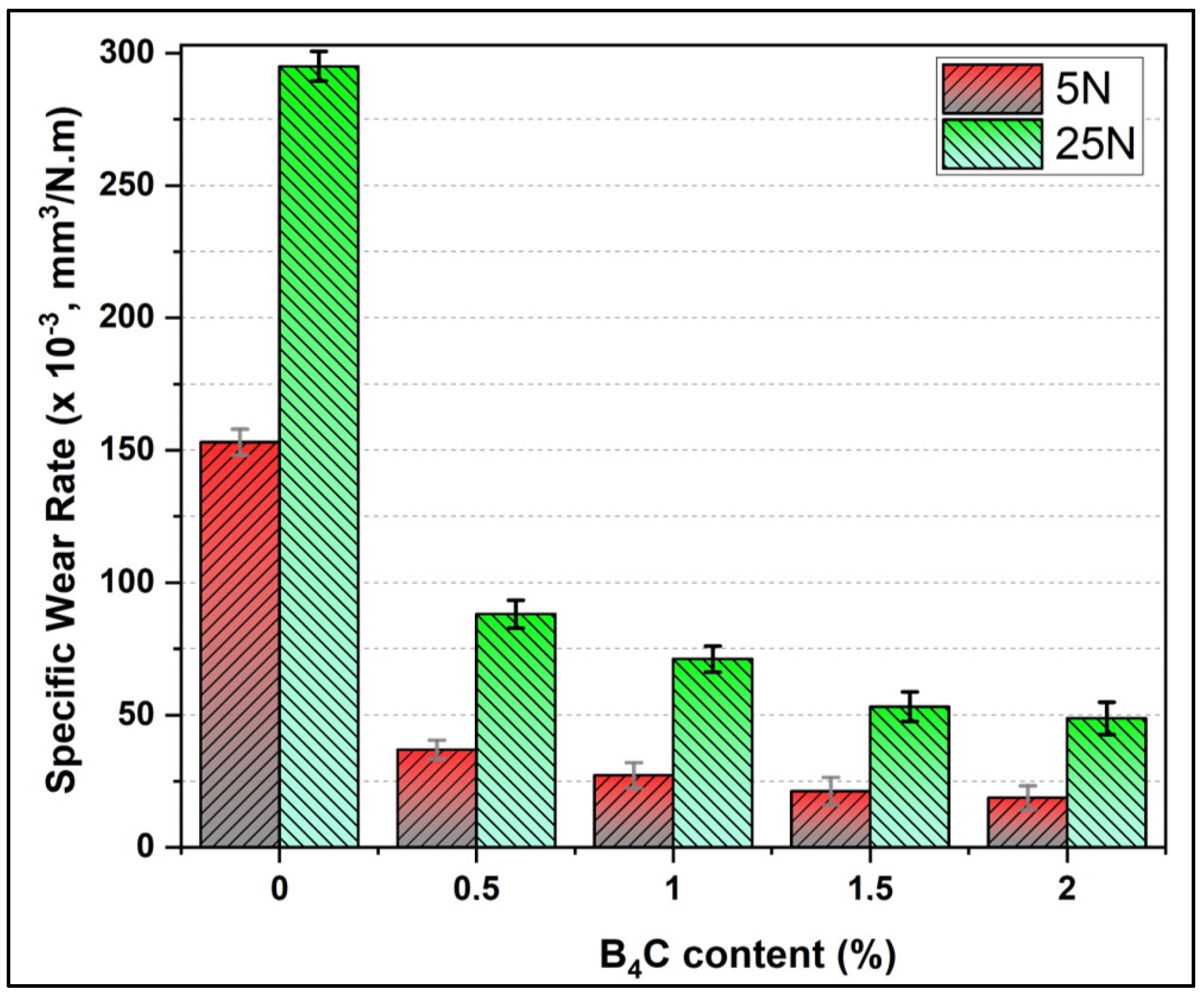

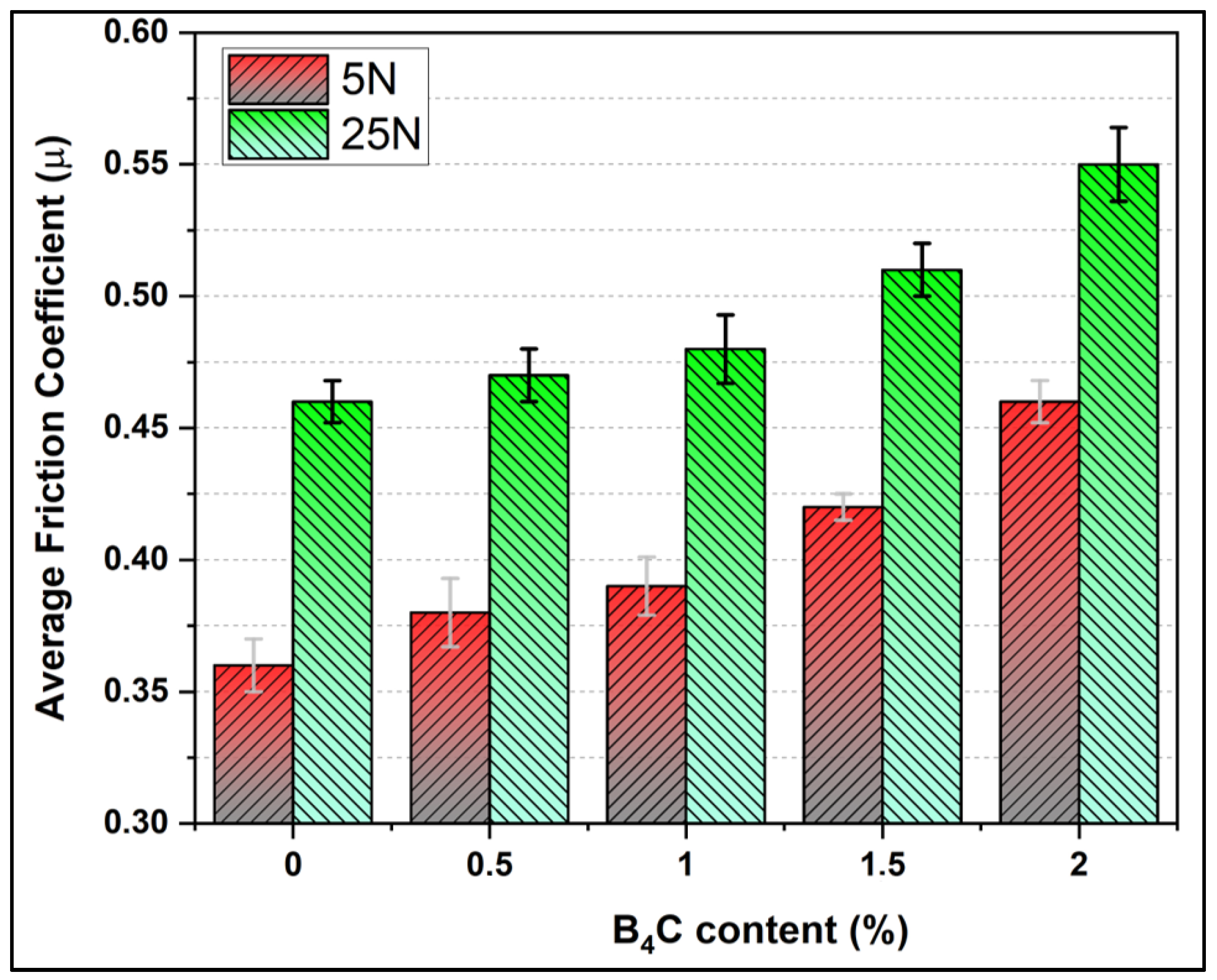

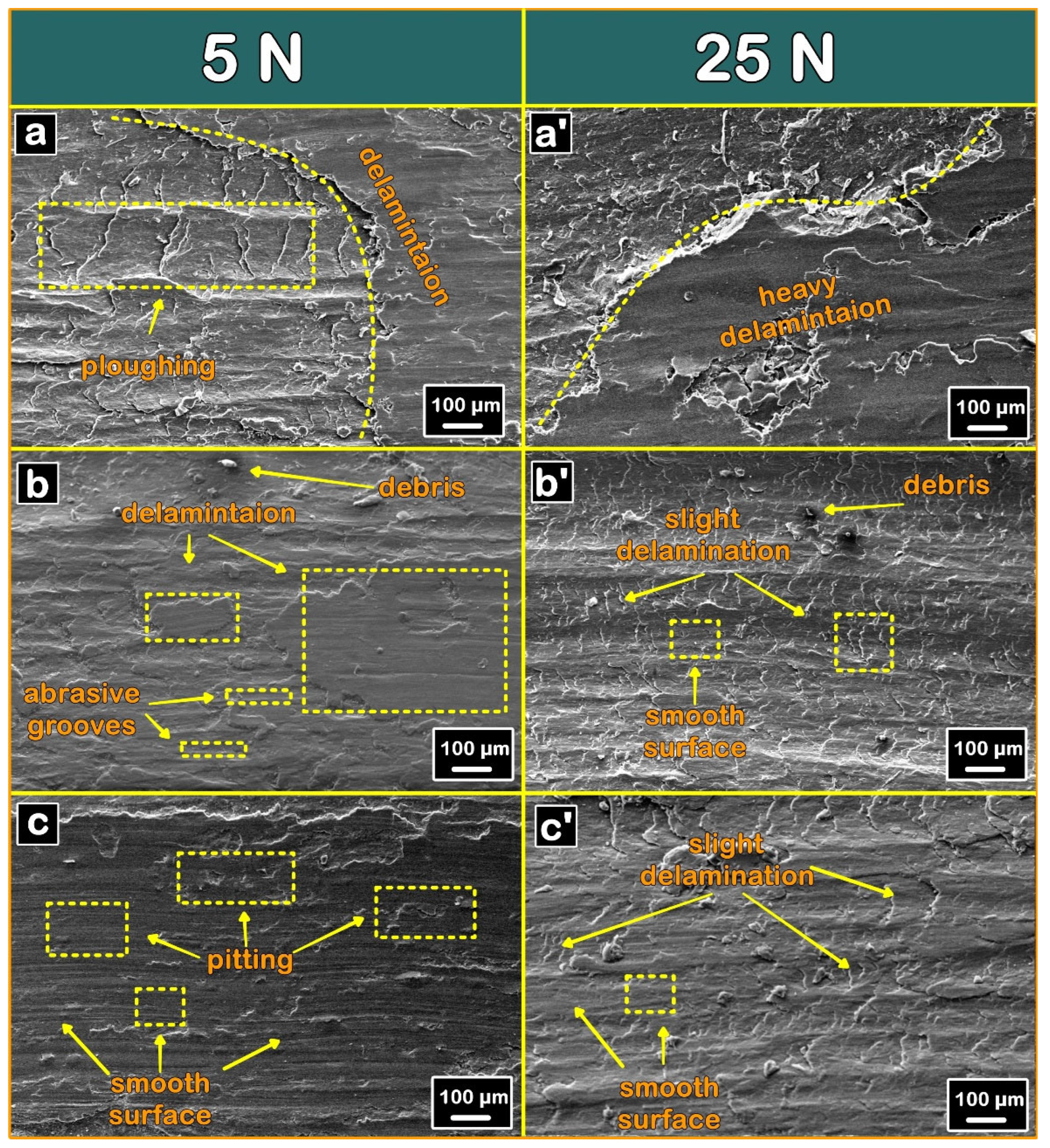

3.6. Wear Behavior

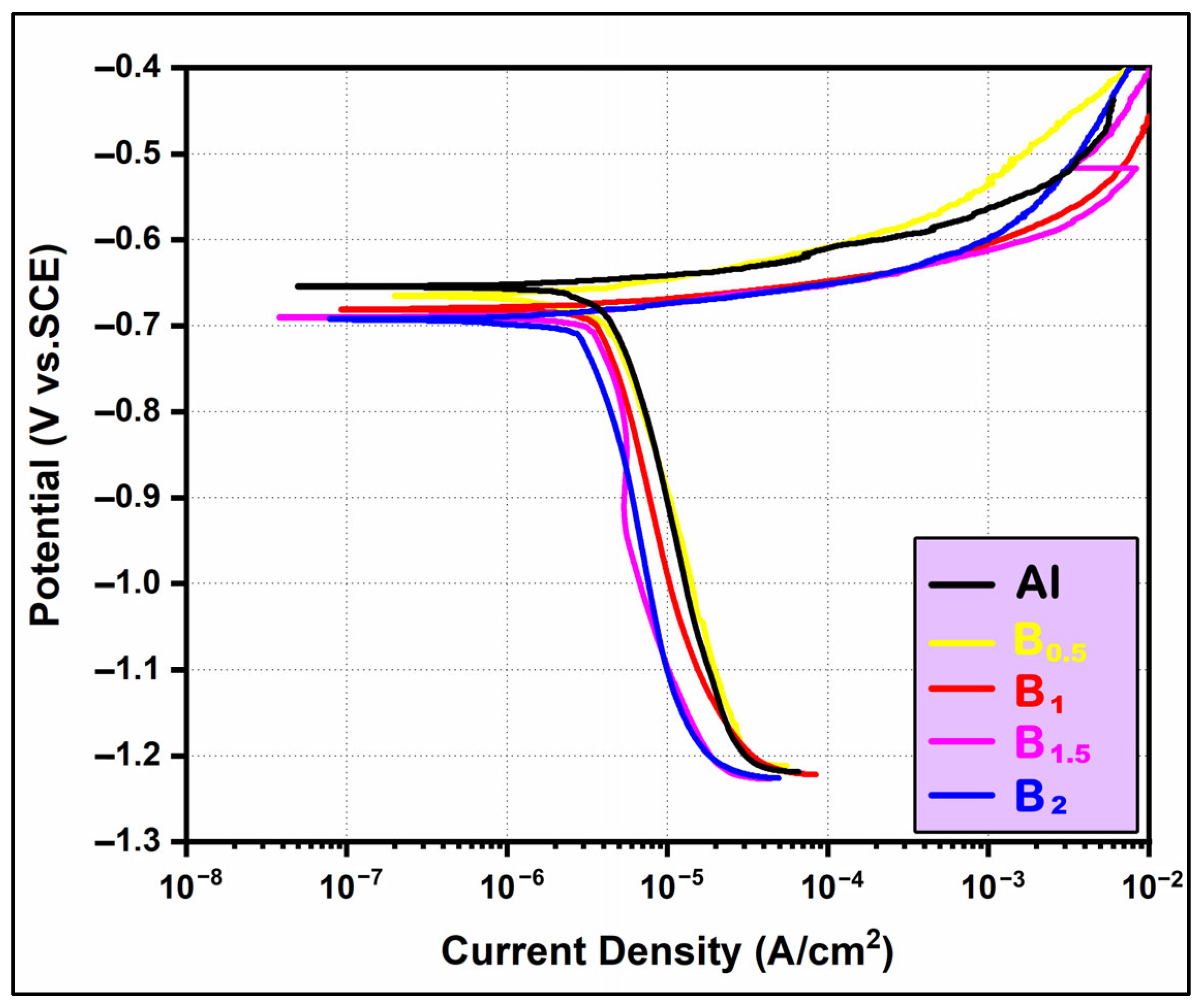

3.7. Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, A.; Singh, V.P.; Singh, R.C.; Chaudhary, R.; Kumar, D.; Mourad, A.-H.I. A Review of Aluminum Metal Matrix Composites: Fabrication Route, Reinforcements, Microstructural, Mechanical, and Corrosion Properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 2644–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, F. Aluminum Alloys for Electrical Engineering: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 14847–14892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çevik, Z.A.; Karabacak, A.H.; Kök, M.; Canakçı, A.; Kumar, S.S.; Varol, T. The Effect of Machining Processes on the Physical and Surface Characteristics of AA2024-B4C-SiC Hybrid Nanocomposites Fabricated by Hot Pressing Method. J. Compos. Mater. 2021, 55, 2657–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, A.H.; Canakci, A.; Özkaya, S.; Tunç, S.A.; Çevik, Z.A.; Yalçın, E.D. The Effects of Different Types and Ratios of Reinforcement, and Machining Processes on the Machinability of Al2024 Alloy Nanocomposites. J. Compos. Mater. 2023, 57, 2811–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalıgülü, U.; Kaçmış, M.V.; Karabacak, A.H.; Çanakçı, A.; Özkaya, S. Investigation of Corrosion Resistance and Impact Performance Properties of Al2O3/SiC-Doped Aluminium-Based Composites. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2023, 46, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwin, A.H.; Ksibi, H. Enhancing High-Temperature Fatigue Performance of AA2024-T4 Alloy Through Shot Peening: A Comprehensive Numerical Simulation. Strength Mater. 2024, 56, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreamlak, G.; Palani, S.; Sirahbizu, B. Mechanical Characteristics of Dissimilar Friction Stir Welding Processes of Aluminium Alloy [AA 2024-T351 and AA 7075-T651]. Manuf. Rev. 2024, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navya, C.; Chandra Sekhara Reddy, M. Contemporary Machining of a Stir Cast Aluminum Alloy Hybrid Metal Matrix Composite: A Study. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2025, 40, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adi, S.S.; Malik, V.R. Friction Stir Processing of Aluminum Machining Waste: Carbon Nanostructure Reinforcements for Enhanced Composite Performance—A Comprehensive Review. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2025, 40, 285–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.R.; Meshram, P.D.; Chakule, R.R.; Gupta, P. Processing of Aluminum Metal Matrix Composite with Titanium Carbide Reinforcement. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2025, 40, 1157–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaratnam, B.; Kmar, S.N.; Seshappa, A.; Raj, K.P.; Jayahari, L.; Prasad, B.A. Improving the Technological Characteristics of an Al-7175/SiC/B4C Composite. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Materials, Manufacturing and Sustainable Development (ICAMMSD 2024), Kurnool, India, 22–23 November 2024; pp. 490–507. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, B.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, X.; Li, Q.; Chang, R.; Wang, Z.; Li, A.; Mu, Y.; et al. Conductive In-Situ B4C/Graphite Composites Prepared by Spark Plasma Sintering Using Nanodiamond as an Additive. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.C.; Harshavardhan, B.; Ashok, B.C. Aluminum Boron Carbide Metal Matrix Composites for Fatigue-Based Applications: A Comprehensive Review. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 24, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Xue, W.; Kang, P.; Chao, Z.; Han, H.; Zhang, R.; Du, S.; Han, B.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, G. Enhanced Ductility of B4C/Al Composites by Controlling Thickness of Interfacial Oxide Layer through High Temperature Oxidation of B4C Particles. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 937, 168486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçın, E.D.; Çanakçı, A.; Çuvalcı, H.; Varol, T.V.; Karabacak, A.H. The Effect of Boron Nitride (h-BN) and Silicon Carbide (SiC) on the Microstructure and Wear Behavior of ZA40/SiC/h-BN Hybrid Composites Processed by Hot Pressing. Kov. Mater.-Met. Mater. 2023, 61, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, M.; Shen, M.; Wei, W. Experimental Investigations on Ultrasonic Elliptical Vibration Turning of SiCp/Al Composites. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2025, 40, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahamtan, S.; Emamy, M.; Halvaee, A. Effects of Reinforcing Particle Size and Interface Bonding Strength on Tensile Properties and Fracture Behavior of Al-A206/Alumina Micro/Nanocomposites. J. Compos. Mater. 2014, 48, 3331–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cicco, D.; Asaee, Z.; Taheri, F. Use of Nanoparticles for Enhancing the Interlaminar Properties of Fiber-Reinforced Composites and Adhesively Bonded Joints—A Review. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baig, Z.; Mamat, O.; Mustapha, M. Recent Progress on the Dispersion and the Strengthening Effect of Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene-Reinforced Metal Nanocomposites: A Review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2018, 43, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Tan, Y.C.; Tai, V.C.; Janasekaran, S.; Kee, C.C.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y. Selective Laser Melting of Titanium Matrix Composites: An in-Depth Analysis of Materials, Microstructures, Defects, and Mechanical Properties. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Chen, Z.; Li, L.; Guo, E.; Kang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, T. Microstructure and Enhanced Mechanical Properties of Hybrid-Sized B4C Particle-Reinforced 6061Al Matrix Composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 802, 140453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommana, D.; Sahoo, N.; Dwivedy, S.K.; Senapati, N.P.; Dora, S.P.; Chintada, S.; Vennela, V.K.L. Investigating the Effect of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Relative Density on the Compressive Properties and Deformation Behaviors of Closed-Cell AA 6061-B4C-SiC-SWCNTs Hybrid Composite Foams. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1034, 181446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, T.; Canakci, A.; Ozkaya, S.; Erdemir, F. Determining the Effect of Flake Matrix Size and Al2O3 Content on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al2O3 Nanoparticle Reinforced Al Matrix Composites. Part. Sci. Technol. 2018, 36, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharath, B.N.; Rao, R. Comparative Study of Mechanical Alloying and Other Conventional Powder Metallurgical Methods. In Mechanical Alloying of Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Alloys; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Révész, Á.; Gajdics, M. Improved H-Storage Performance of Novel Mg-Based Nanocomposites Prepared by High-Energy Ball Milling: A Review. Energies 2021, 14, 6400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Seetharam, R.; Ponappa, K. Effects of Graphene Nano Particles on Interfacial Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al7150/B4C Hybrid Nanocomposite Fabricated by Novel Double Ultrasonic Two Stage Stir Casting Technique. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1008, 176686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudina, D.V.; Bokhonov, B.B. Materials Development Using High-Energy Ball Milling: A Review Dedicated to the Memory of M.A. Korchagin. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alem, S.A.A.; Sabzvand, M.H.; Govahi, P.; Poormehrabi, P.; Hasanzadeh Azar, M.; Salehi Siouki, S.; Rashidi, R.; Angizi, S.; Bagherifard, S. Advancing the next Generation of High-Performance Metal Matrix Composites through Metal Particle Reinforcement. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 2025, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, K.S.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, D.; Lin, J.; Li, Y.; Wen, C. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Carbon Nanotubes Reinforced Titanium Matrix Composites Fabricated via Spark Plasma Sintering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 688, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Mei, Q.S.; Liao, L.Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z.H.; Wang, Y.C.; Li, J.Y. A Comparative Study on the Microstructure and Strengthening Behaviors of Al Matrix Composites Containing Micro- and Nano-Sized B4C Particles. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 874, 145066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Beni, H.A. Strength Prediction of the ARBed Al/Al2O3/B4C Nano-Composites Using Orowan Model. Mater. Res. Bull. 2014, 59, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Z.L.; Sun, T.T.; Jiang, L.T.; Zhou, Z.S.; Chen, G.Q.; Wu, G.H. Ballistic Behavior and Microstructure Evolution of B4C/AA2024 Composites. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 20539–20544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylan, Y.; Avar, B.; Panigrahi, M.; Aygün, B.; Karabulut, A. Effect of the B4C Content on Microstructure, Microhardness, Corrosion, and Neutron Shielding Properties of Al–B4C Composites. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 5479–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, S.; Bhandari, R.; Paul, T.; Samanta, S.K.; Mondal, M.K. Development of Novel Nano-B4C and CNF Reinforced Aluminium Matrix Hybrid Nanocomposite. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 41, 1442–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyaz, M.S.B.; Singh, J.; Bhati, S.S.; Mehdi, H.; Mishra, S. Evolution of Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Tribological Behavior of AA2024/B4C/Al2O3 Nanocomposites Fabricated by Multi-Pass FSP. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 25831–25849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebi, M.; Çanakçı, A.; Özkaya, S. Effect of Mechanical Milling Time on Powder Characteristic, Microstructure, and Mechanical Properties of AA2024/B4C/GNPs Hybrid Nanocomposites. Powder Technol. 2025, 449, 120439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebi, M.; Çanakçı, A.; Özkaya, S. Comparative Study of Powder Characteristics and Mechanical Properties of Al2024 Nanocomposites Reinforced with Carbon-Based Additives. Adv. Powder Technol. 2025, 36, 104835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoi, N.K.; Singh, H.; Pratap, S. Developments in the Aluminum Metal Matrix Composites Reinforced by Micro/Nano Particles—A Review. J. Compos. Mater. 2020, 54, 813–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, S.R.; Maledi, N.; Okanlawon, I.A.; Bishi, T.R.; Falodun, O.E. Tensile and Corrosion Properties of Copper and Alumina Hybrid Reinforcement on Aluminum Matrix Composite. J. Compos. Mater. 2025, 59, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunç, S.A.; Çanakçı, A.; Karabacak, A.H.; Çelebi, M.; Türkmen, M. Effect of Different PCA Types on Morphology, Physical, Thermal and Mechanical Properties of AA2024-B4C Composites. Powder Technol. 2024, 434, 119373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alihosseini, H.; Dehghani, K.; Kamali, J. Microstructure Characterization, Mechanical Properties, Compressibility and Sintering Behavior of Al-B4C Nanocomposite Powders. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 2126–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, T.; Canakci, A. Effect of Particle Size and Ratio of B4C Reinforcement on Properties and Morphology of Nanocrystalline Al2024-B4C Composite Powders. Powder Technol. 2013, 246, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medjkoune, M.; Bottin-Rousseau, S.; Carroz, L.; Soucek, R.; Prévot, G.; Croset, B.; Micha, J.-S.; Akamatsu, S. Eutectic Grains and Orientation Relationships in Thin Directionally Solidified Al-Al2Cu Samples: A Laue Micro-Diffraction Study. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1036, 181841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çanakçı, A.; Çelebi̇, M. Determination of Nano-Graphene Content for Improved Mechanical and Tribological Performance of Zn-Based Alloy Matrix Hybrid Nanocomposites. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1001, 175152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, M.; Xiao, D.; Ma, Y.; Liu, W. Effect of Minor La Addition on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Cast Al-Cu-Mn Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1021, 179747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, S.R.; Maledi, N.; Salaudeen, I.; Falodun, O.E. Exploring the Synergistic Effects of Cu and Al2O3 Reinforcements on Nanoindentation and Wear Properties of Aluminum Based Composite. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąsik, A.; Leszczyńska-Madej, B.; Madej, M.; Goły, M. Effect of Heat Treatment on Microstructure of Al4Cu-SiC Composites Consolidated by Powder Metallurgy Technique. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Sun, L.; Chen, D. Improving the Mechanical Properties of B4C/Al Composites by Solid-State Interfacial Reaction. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 829, 154521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosedag, E.; Ekici, R. Low-Velocity Impact Behaviors of B4C/SiC Hybrid Ceramic Reinforced Al6061 Based Composites: An Experimental and Numerical Study. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Monetta, T. Systematic Study of Preparation Technology, Microstructure Characteristics and Mechanical Behaviors for SiC Particle-Reinforced Metal Matrix Composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 7470–7497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balog, M.; Krížik, P.; Školáková, A.; Švec, P.; Kubásek, J.; Pinc, J.; de Castro, M.M.; Figueiredo, R. Hall-Petch Strengthening in Ultrafine-Grained Zn with Stabilized Boundaries. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 7458–7468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasani, F.; Taheri, A.K.; Bahrami, H.; Pouranvari, M. Plastic Deformation and Fracture of AlMg6/CNT Composite: A Damage Evolution Model Coupled with a Dislocation-Based Deformation Model. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouraliakbar, H.; Jandaghi, M.R. Mechanistic Insight into the Role of Severe Plastic Deformation and Post-Deformation Annealing in Fracture Behavior of Al-Mn-Si Alloy. Mech. Mater. 2018, 122, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, D.C.C.; Klıauga, A.M.; Sordı, V.L. Flow Behavior and Fracture of Al−Mg−Si Alloy at Cryogenic Temperatures. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A.; Alizadeh, A.; Baharvandi, H.R. Dry Sliding Tribological Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Al2024–5 wt.%B4C Nanocomposite Produced by Mechanical Milling and Hot Extrusion. Mater. Des. 2014, 55, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaral, M.; Deshapande, R.G.; Auradi, V.; Boppana, S.B.; Dayanand, S.; Anilkumar, M.R. Mechanical and Wear Characterization of Ceramic Boron Carbide-Reinforced Al2024 Alloy Metal Composites. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros 2021, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, Z.; Luo, Y.; Gao, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, Y.; Wu, C.; Jin, M. Influence of Synergistic Strengthening Effect of B4C and TiC on Tribological Behavior of Copper-Based Powder Metallurgy. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 2978–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajević, S.; Miladinović, S.; Güler, O.; Özkaya, S.; Stojanović, B. Optimization of Dry Sliding Wear in Hot-Pressed Al/B4C Metal Matrix Composites Using Taguchi Method and ANN. Materials 2024, 17, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, V.; Shelly, D.; Babbar, A.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J. Review of Wear and Mechanical Characteristics of Al-Si Alloy Matrix Composites Reinforced with Natural Minerals. Lubricants 2024, 12, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Gao, Z.; Fan, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. Exceptional Mechanical Performance and Macroscale Superlubricity Enabled by Core-Shell-like MoS2/B4C Film. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2024, 67, 2018–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanikumar, K.; Eaben Rajkumar, S.; Pitchandi, K. Influence of Primary B4C Particles and Secondary Mica Particles on the Wear Performance of Al6061/B4C/Mica Hybrid Composites. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros 2019, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özler, L.; Tosun, G.; Özcan, M.E. Influence of B4C Powder Reinforcement on Coating Structure, Microhardness and Wear in Friction Surfacing. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2020, 35, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghwal, A.; Anupam, A.; Schulz, C.; Hall, C.; Murty, B.S.; Kottada, R.S.; Vijay, R.; Munroe, P.; Berndt, C.C.; Ang, A.S.M. Tribological and Corrosion Performance of an Atmospheric Plasma Sprayed AlCoCr0.5Ni High-Entropy Alloy Coating. Wear 2022, 506–507, 204443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Egidio, G.; Martini, C.; Börjesson, J.; Ghassemali, E.; Ceschini, L.; Morri, A. Dry Sliding Behavior of AlSi10Mg Alloy Produced by Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion: Influence of Heat Treatment and Microstructure. Wear 2023, 516–517, 204602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ma, Y.; Ma, S.; Xiong, H.; Chen, B. Mechanical Properties and Corrosion Resistance Enhancement of 2024 Aluminum Alloy for Drill Pipe after Heat Treatment and Sr Modification. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, X.; An, X.; Zong, L.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, H.; Sui, Y.; Sun, W. Tailoring Precipitate Distribution in 2024 Aluminum Alloy for Improving Strength and Corrosion Resistance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 194, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, O.; Jiang, D.; Feenstra, D.R.; Kairy, S.K.; Wu, Y.; Hutchinson, C.R.; Birbilis, N. On the Corrosion of Additively Manufactured Aluminium Alloy AA2024 Prepared by Selective Laser Melting. Corros. Sci. 2018, 143, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Jiang, L.; Chao, Z.; Xue, W.; Zhu, M.; Han, B.; Zhang, R.; Du, S.; Luo, T.; Mei, Y. Revealing Corrosion Behavior of B4C/Pure Al Composite at Different Interfaces between B4C Particles and Al Matrix in NaCl Electrolyte. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 7213–7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S.K.; Bhandari, H.; Ruhi, G.; Bisht, B.M.S.; Sambyal, P. Corrosion Preventive Materials and Corrosion Testing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781315101217. [Google Scholar]

- Erdemir, F.; Canakci, A.; Varol, T.; Ozkaya, S. Corrosion and Wear Behavior of Functionally Graded Al2024/SiC Composites Produced by Hot Pressing and Consolidation. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 644, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lyu, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Jiang, J.; Jiang, X. Recent Progress on Corrosion Mechanisms of Graphene-Reinforced Metal Matrix Composites. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2023, 12, 20220566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Jiang, L.; Kang, P.; Yang, W.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Liu, H.; Wu, G. Design and Fabrication of a Nanoamorphous Interface Layer in B4C/Al Composites to Improve Hot Deformability and Corrosion Resistance. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 5752–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutuk, S. Morphology, Crystal Structure and Thermal Properties of Nano-sized Amorphous Colemanite Synthesis. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 11699–11716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guner, N.U.; Kutuk, S.; Kutuk-Sert, T. Role of Calcination Process of Natural Colemanite Powder on Compressive Strength Property of Concrete. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cu | Mg | Mn | Fe | Si | Zn | Cr | Ti | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.85 | 1.78 | 0.312 | 0.374 | 0.385 | 0.138 | 0.042 | 0.005 | Balance |

| Sample Code | Reinforcement Content | Milling Time (h) | Milling Speed (rpm) | BPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | - | - | - | - |

| B0.5 | 0.5 | 8 | 300 | 5:1 |

| B1 | 1 | 8 | 300 | 5:1 |

| B1.5 | 1.5 | 8 | 300 | 5:1 |

| B2 | 2 | 8 | 300 | 5:1 |

| Point | Al | Cu | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 46.21 | 52.89 | 0.9 |

| B | 95.27 | 2.03 | 2.7 |

| Symbol | Icorr (µA) | Ecorr (mV) | Corrosion Rate (mpy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 5.68 | −654 | 8.014 |

| B0.5 | 4.97 | −665 | 7.127 |

| B1 | 4.45 | −681 | 6.573 |

| B1.5 | 4.24 | −690 | 5.925 |

| B2 | 3.47 | −689 | 4.897 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Çelebi, M.; Çanakçı, A.; Kütük, S. Influence of Nano-Sized Ceramic Reinforcement Content on the Powder Characteristics and the Mechanical, Tribological, and Corrosion Properties of Al-Based Alloy Nanocomposites. Coatings 2026, 16, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010143

Çelebi M, Çanakçı A, Kütük S. Influence of Nano-Sized Ceramic Reinforcement Content on the Powder Characteristics and the Mechanical, Tribological, and Corrosion Properties of Al-Based Alloy Nanocomposites. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010143

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇelebi, Müslim, Aykut Çanakçı, and Sezai Kütük. 2026. "Influence of Nano-Sized Ceramic Reinforcement Content on the Powder Characteristics and the Mechanical, Tribological, and Corrosion Properties of Al-Based Alloy Nanocomposites" Coatings 16, no. 1: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010143

APA StyleÇelebi, M., Çanakçı, A., & Kütük, S. (2026). Influence of Nano-Sized Ceramic Reinforcement Content on the Powder Characteristics and the Mechanical, Tribological, and Corrosion Properties of Al-Based Alloy Nanocomposites. Coatings, 16(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010143