3.1. Microstructural Evolution and Bonding Mechanism

To understand detailed bonding mechanisms in CM247LC requires direct resolution of interfacial morphology, reaction-layer development, and local microstructural evolution. Accordingly, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed as the primary characterization tool to simultaneously assess interlayer geometry, interface roughness, and reaction-driven microstructural features as a function of holding time. Quantitative interlayer thickness values (mean ± standard deviation) were extracted directly from SEM micrographs, enabling correlation between geometric evolution and underlying bonding mechanisms.

SEM micrographs in

Figure 1a–e reveal a reaction-stabilized interlayer in CM247LC joints bonded with MBF-80 across the entire holding-time range (0–120 min). In the as-bonded condition (

Figure 1a, 0 min), a clearly defined interlayer with an average thickness of 55.8 ± 2.2 µm is observed. The interlayer exhibits a highly irregular morphology with serrated interfaces and local penetration features, indicative of aggressive substrate dissolution and rapid formation of a liquid-derived reaction zone.

After a holding time of 10 min (

Figure 1b), the interlayer thickens substantially to 67.5 ± 2.8 µm, accompanied by increased morphological complexity. Rather than smoothing, the interface becomes more convoluted, suggesting that continued dissolution and interfacial reactions outweigh diffusion-driven stabilization at early bonding stages.

At 30 min (

Figure 1c), the interlayer remains continuous and chemically distinct, with a thickness of 65.7 ± 2.4 µm. The interface retains a jagged, non-planar character, confirming that the joint has not transitioned toward homogenization or isothermal solidification.

Although the apparent interlayer thickness locally decreases to 40.1 ± 3.3 µm at 60 min (

Figure 1d), SEM observations still reveal a clearly defined reaction zone with persistent interface roughness. This reduction does not correspond to interlayer elimination but rather reflects local redistribution or rearrangement of reaction products within a chemically stabilized zone.

After prolonged holding for 120 min (

Figure 1e), the interlayer again increases to 68.2 ± 1.7 µm, demonstrating non-monotonic thickness evolution. The persistence and fluctuation of a relatively thick interlayer, together with sustained interface roughness, clearly indicate that isothermal solidification does not occur in the MBF-80 system. Instead, bonding proceeds via a reaction-dominated brazing mechanism, in which interlayer stabilization overrides diffusion-assisted homogenization.

The SEM morphology strongly suggests the formation and stabilization of boron-containing intermetallic reaction products, likely involving refractory elements such as W and Cr. These reaction phases act as effective diffusion barriers, chemically immobilizing boron within the interlayer and suppressing its depletion into the CM247LC substrate, thereby inhibiting isothermal solidification.

In contrast, SEM micrographs of CM247LC joints bonded with MBF-20 (

Figure 2a–e) exhibit a fundamentally different interfacial evolution, characterized by progressive interface smoothing and geometric stability.

At 0 min (

Figure 2a), the interlayer is already thinner and more uniform than in MBF-80, with an average thickness of 30.4 ± 2.1 µm. The interfaces appear relatively smooth, indicating restrained substrate dissolution and more controlled liquid formation.

After 10 min (

Figure 2b), the interlayer thickness slightly decreases to 27.5 ± 2.5 µm, and the interface becomes more planar, suggesting that diffusion processes begin to counterbalance dissolution-driven reactions at an early stage.

By 30 min (

Figure 2c), the interlayer remains geometrically stable at 29.7 ± 2.8 µm, while reaction-induced roughness is further suppressed. The interface becomes difficult to delineate, indicating progressive chemical equilibration rather than reaction-layer amplification.

At extended holding times of 60 min (

Figure 2d) and 120 min (

Figure 2e), the interlayer thickness remains nearly constant at 30.1 ± 1.8 µm and 32.7 ± 2.2 µm, respectively. SEM images reveal a microstructure increasingly similar to that of the CM247LC base metal, with no evidence of a stabilized reaction layer.

The geometric stability and progressive interface smoothing observed across

Figure 2a–e indicate that MBF-20 enables a diffusion-assisted bonding pathway. Here, partial isothermal solidification refers to a bonding state in which diffusion-driven depletion of boron and compositional equilibration significantly suppress a chemically and mechanically distinct reaction layer, even though a thin residual interlayer remains microscopically detectable.

This behavior is characterized by the absence of refractory-element-enriched reaction products, progressive interfacial smoothing, and convergence of the joint microstructure toward that of the CM247LC substrate. Accordingly, partial isothermal solidification in the MBF-20 joints reflects effective chemical and mechanical continuity achieved through diffusion-assisted equilibration, rather than complete geometric elimination of the interlayer.

Although SEM reveals the morphological evolution of the joint region, it cannot directly resolve the elemental redistribution responsible for interlayer stabilization or elimination. Accordingly, Electron probe micro analyzer (EPMA) elemental mapping was performed to track the time-dependent diffusion and retention of boron and associated alloying elements, thereby providing chemical-level evidence for the underlying bonding mechanisms.

Figure 3 presents EPMA elemental maps of the CM247LC joints bonded with MBF-80 at representative holding times of 0, 30, and 120 min, providing direct insight into the time-dependent chemical evolution of the interlayer. Immediately after reaching the bonding temperature (

Figure 3a, 0 min), boron is intensely concentrated within a narrow interlayer region, forming a sharply defined B-rich domain that is chemically discontinuous from the surrounding CM247LC substrate. The localization of boron at this early stage indicates rapid melting of the filler metal and immediate enrichment of the interlayer by the melting-point depressant, with negligible diffusion into the substrate. Concurrently, the distributions of Ni, Cr, and Co remain largely continuous across the interface, suggesting that bulk elemental redistribution has not yet occurred.

Although not explicitly shown in

Figure 3a, EPMA maps obtained at 10 min reveal that the boron-rich interlayer remains highly localized, with only limited broadening of the B signal toward the substrate. This persistence of boron within the interlayer at an early holding stage indicates that MPD depletion does not proceed readily in the MBF-80 system. At the same time, incipient enrichment of refractory elements such as W becomes detectable near the interlayer–substrate boundary, implying the onset of reaction-assisted trapping of boron. The spatial co-localization of boron with refractory elements at this stage suggests the early formation of thermodynamically stable reaction products rather than transient solute segregation.

At an intermediate holding time of 30 min (

Figure 3b), the boron-enriched interlayer remains clearly identifiable and becomes chemically more heterogeneous. EPMA maps show intensified accumulation of W at the interface, spatially correlated with the boron-rich regions, strongly indicating the formation and growth of refractory-element borides, such as W- and Cr-containing boride phases, which are known to exhibit high thermal stability and limited diffusivity in Ni-based systems. The co-localization of boron and refractory elements indicates that boron diffusion into the CM247LC substrate is increasingly suppressed by chemical immobilization within stable reaction layers, rather than by kinetic limitation alone [

9]. Supplemental EPMA data at 60 min further support this interpretation, as strong boron retention within the interlayer persists, accompanied by pronounced refractory-element pile-up, rather than any trend toward compositional smoothing.

After prolonged holding for 120 min (

Figure 3c), the boron-rich domains remain distinctly visible within the interlayer, and the chemical contrast between the interlayer and the substrate is not alleviated. Instead of approaching compositional homogenization, the interlayer exhibits stabilized reaction products, with persistent boron enrichment and refractory accumulation. Even at this extended holding time, no evidence of boron depletion or diffusion-driven interlayer disappearance is observed. This explicit time-resolved EPMA evolution demonstrates that, in the MBF-80 joints, MPD depletion is kinetically suppressed throughout the entire bonding process. As a result, isothermal solidification does not occur, and the joint evolution is governed by a reaction-stabilized, brazing-dominant bonding mechanism.

By contrast,

Figure 4 presents EPMA elemental maps of CM247LC joints bonded with MBF-20 at identical holding times, illustrating a diffusion-assisted chemical evolution of the interlayer. At 0 min (

Figure 4a), boron is detected within the interlayer; however, its intensity is significantly lower, and its spatial distribution is less sharply confined than that observed in the MBF-80 joints. The B signal already exhibits a smoother compositional transition toward the CM247LC substrate, indicating that boron diffusion is not immediately inhibited. Elemental maps of Ni, Cr, and Co remain largely continuous, while no pronounced accumulation of refractory elements is observed at the interface.

EPMA data obtained at 10 min indicate that the boron signal within the interlayer weakens further and begins to broaden into the adjacent substrate, marking the onset of effective MPD diffusion. Unlike the MBF-80 system, no evidence of boron trapping or refractory-element pile-up is detected at this stage. By 30 min (

Figure 4b), the boron concentration within the interlayer is further reduced, and a more continuous diffusion gradient extending into the CM247LC substrate becomes evident. The absence of localized boron–refractory co-localization suggests that stable boride formation is suppressed in the MBF-20 joints.

At 60 min, EPMA maps show that boron-rich domains within the interlayer are largely diminished, and the elemental distributions of Ni, Cr, Co, and Al across the joint become increasingly uniform. This evolution reflects progressive chemical equilibration driven by diffusion rather than reaction-layer stabilization. After extended holding for 120 min (

Figure 4c), the boron signal within the interlayer remains weak and diffuse, and the chemical distinction between the interlayer and the substrate is substantially reduced. Although a thin interlayer may still be discernible, the overall compositional continuity across the joint indicates advanced MPD depletion and diffusion-assisted homogenization. This time-dependent EPMA evolution confirms that MBF-20 promotes a diffusion-assisted bonding pathway, leading toward partial isothermal solidification, in stark contrast to the reaction-stabilized behavior observed in the MBF-80 system.

3.2. Hardness Distribution and Its Correlation with Microstructural Evolution

To assess whether the reaction-dominated and diffusion-assisted bonding mechanisms identified in the preceding microstructural analyses result in distinct mechanical responses, microhardness profiles were measured across the joint region.

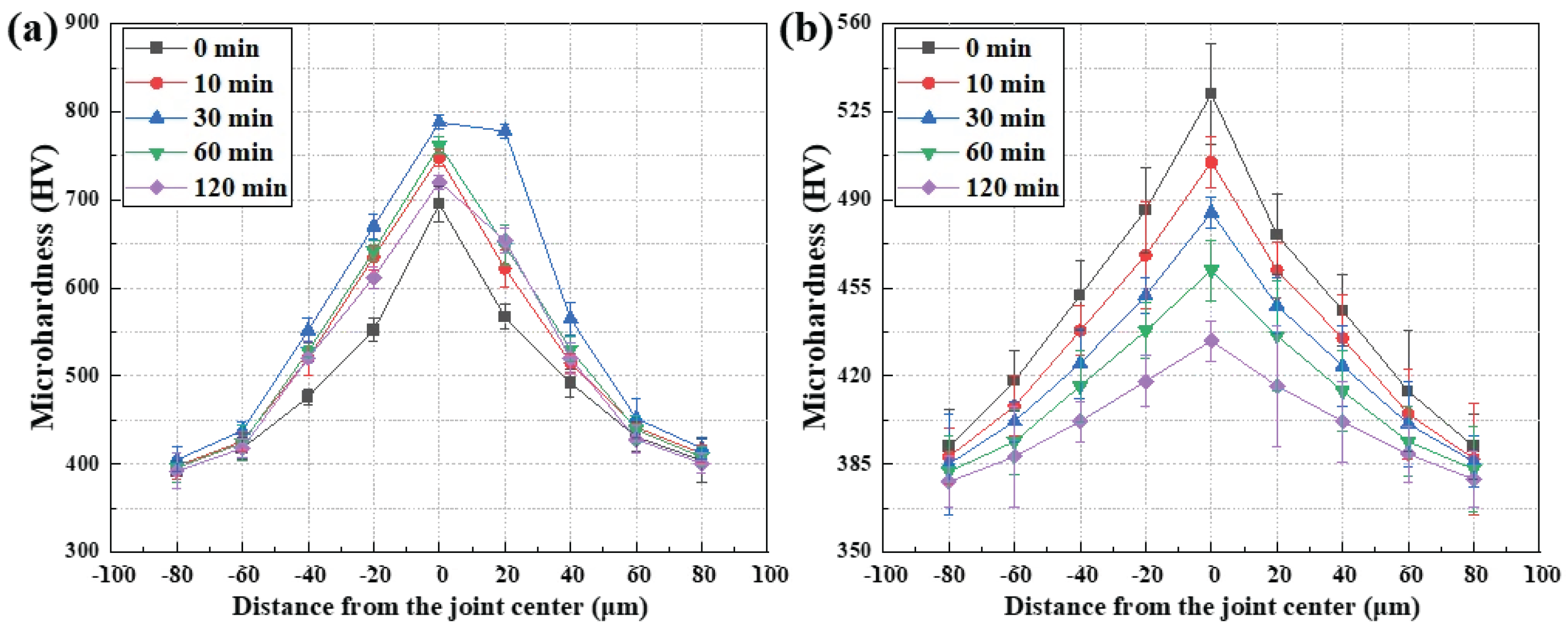

Figure 5 presents the hardness distributions across CM247LC joints bonded with MBF-80 and MBF-20 as a function of holding time. The measurements were performed along a normal line to the joint interface, enabling direct correlation between spatial variations in hardness and the interlayer morphology and chemical distributions revealed by OM, SEM, and EPMA.

As shown in

Figure 5a, the MBF-80 joints exhibit a pronounced and persistent hardness peak centered at the interlayer for all holding times. Even in the as-bonded condition (0 min), the hardness at the joint center is significantly higher than that of the CM247LC base metal, indicating the early formation of mechanically hard phases immediately following melting and solidification of the filler. This observation is consistent with OM results showing a distinct liquid-derived interlayer and SEM images revealing a rough, reaction-dominated interface at short holding times. With increasing holding time to 10 and 30 min, the peak hardness becomes more prominent and the hardness gradient between the interlayer and the adjacent substrate steepens. Rather than diminishing, the mechanically distinct interlayer becomes increasingly stabilized. EPMA results demonstrate that boron remains strongly localized within the interlayer and is spatially correlated with refractory elements such as W and Cr, indicating the formation and growth of boron-containing intermetallic compounds. These reaction products possess intrinsically high hardness and act as chemically stable phases that inhibit diffusion-assisted homogenization. At extended holding times of 60 and 120 min, the hardness profiles of the MBF-80 joints show no tendency to converge toward the base-metal hardness. Although minor fluctuations in peak magnitude are observed, the hardness remains highly localized at the joint center. This persistent mechanical heterogeneity mirrors the reaction-stabilized microstructure observed in SEM and the sustained boron enrichment detected by EPMA, confirming that isothermal solidification does not occur. Instead, bonding in the MBF-80 system is governed by a brazing-dominant mechanism in which reaction-layer stabilization overrides diffusion-driven chemical equilibration.

In contrast, the hardness distributions of the MBF-20 joints shown in

Figure 5b display a fundamentally different time-dependent evolution. In the as-bonded state (0 min), only a modest hardness increase is observed at the joint center, and the hardness gradient across the joint is comparatively gentle. This behavior reflects the limited formation of hard reaction products during initial bonding, in agreement with the smoother interlayer morphology observed by SEM and the weaker boron localization revealed by EPMA. As the holding time increases to 10 and 30 min, the maximum hardness at the joint center decreases progressively, and the hardness profiles become broader and flatter. This evolution coincides with the gradual depletion and redistribution of boron from the interlayer into the CM247LC substrate, as evidenced by EPMA elemental maps. The absence of pronounced refractory-element accumulation suppresses the stabilization of boron-rich intermetallic phases, preventing the formation of a mechanically distinct reaction layer. At holding times of 60 and 120 min, the hardness across the MBF-20 joints approaches that of the CM247LC base metal, and the hardness profiles become nearly uniform across the joint region. This convergence reflects advanced chemical homogenization and mechanical continuity, consistent with the disappearance of a morphologically distinct interlayer in SEM observations. Therefore, the progressive flattening and convergence of hardness profiles in the MBF-20 joints signify enhanced macroscopic mechanical compatibility with the CM247LC substrate, arising from diffusion-assisted chemical homogenization rather than reaction-layer stabilization.

To provide a more rigorous and quantitative basis for the interpretation of hardness profile evolution,

Table 3 and

Table 4 report the Vickers microhardness statistics (mean ± standard deviation), together with the corresponding maximum and minimum values, measured across the joint region and the CM247LC base metal for MBF-80 and MBF-20 joints, respectively.

For the MBF-80 joints (

Table 3), the joint-center hardness (0 µm) exhibits consistently elevated mean values relative to the substrate at all holding times. In the as-bonded condition, the joint center shows a hardness of 695 ± 20 HV, compared with 392–418 HV in the base metal region (±80–60 µm). With increasing holding time, the maximum hardness further increases, reaching 788 ± 8 HV at 30 min, while the minimum hardness in the substrate remains nearly unchanged at approximately 400 HV, resulting in a peak-to-valley hardness difference exceeding 380 HV. Even after prolonged holding for 120 min, the joint center retains a high hardness of 720 ± 8 HV, whereas the base metal remains in the range of 401–418 HV, confirming the persistence of a pronounced mechanical mismatch across the joint. The associated standard deviations near the interlayer (typically ±8–20 HV) further indicate local microstructural heterogeneity associated with reaction-stabilized interlayers.

In contrast, the MBF-20 joints (

Table 4) display a progressive reduction in both hardness magnitude and spatial contrast with holding time. At 0 min, the joint center hardness is 532 ± 20 HV, compared with 392–418 HV in the substrate. With increasing holding time, the joint-center hardness decreases monotonically to 505 ± 10 HV (10 min), 485 ± 6 HV (30 min), 462 ± 12 HV (60 min), and 434 ± 8 HV (120 min). Simultaneously, the hardness range across the joint narrows substantially, with the maximum–minimum difference decreasing from approximately 140 HV at 0 min to less than 60 HV at 120 min. The relatively uniform standard deviations across the joint region (typically ±8–24 HV) further indicate reduced mechanical heterogeneity.

From a macroscopic mechanical perspective, these quantitative trends demonstrate that persistent hardness localization and large max–min differences in the MBF-80 joints correspond to significant stiffness mismatch and potential stress concentration at the interlayer, whereas the progressive reduction in mean hardness contrast and statistical scatter in the MBF-20 joints reflects improved mechanical compatibility and load-transfer continuity with the CM247LC substrate. Thus, the hardness statistics reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4 quantitatively substantiate the profile flattening behavior observed in

Figure 5 and reinforce the mechanistic distinction between reaction-dominated and diffusion-assisted bonding pathways.

This convergence reflects diffusion-assisted chemical homogenization, whereby the melting-point depressant is substantially depleted and chemical gradients across the joint are significantly reduced. In this context, partial isothermal solidification refers to the effective suppression of a mechanically and chemically distinct interlayer through diffusion-driven equilibration, even if a thin residual interlayer remains microscopically detectable.

Overall, the contrasting hardness behaviors of MBF-80 and MBF-20 provide a clear mechanical manifestation of their respective bonding mechanisms. While MBF-80 maintains localized high hardness due to the stabilization of boron-rich intermetallic reaction layers, MBF-20 exhibits progressive hardness homogenization driven by diffusion-assisted chemical equilibration. Persistent hardness localization in the MBF-80 joints signifies mechanically heterogeneous, reaction-stabilized interlayers, whereas the progressive flattening and convergence of hardness profiles in the MBF-20 joints indicate improved chemical and mechanical continuity with the CM247LC substrate. These results emphasize that higher joint hardness does not necessarily correspond to a more favorable bonding outcome; rather, for CM247LC, the ability of MBF-20 to achieve mechanical compatibility with the base metal through TLP-like bonding is expected to be advantageous for joint reliability and resistance to stress concentration.