Enhanced Corrosion Resistance of Water-Based Aluminum Phosphate Coatings via Graphene Oxide Modification: Mechanisms and Long-Term Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Substrate

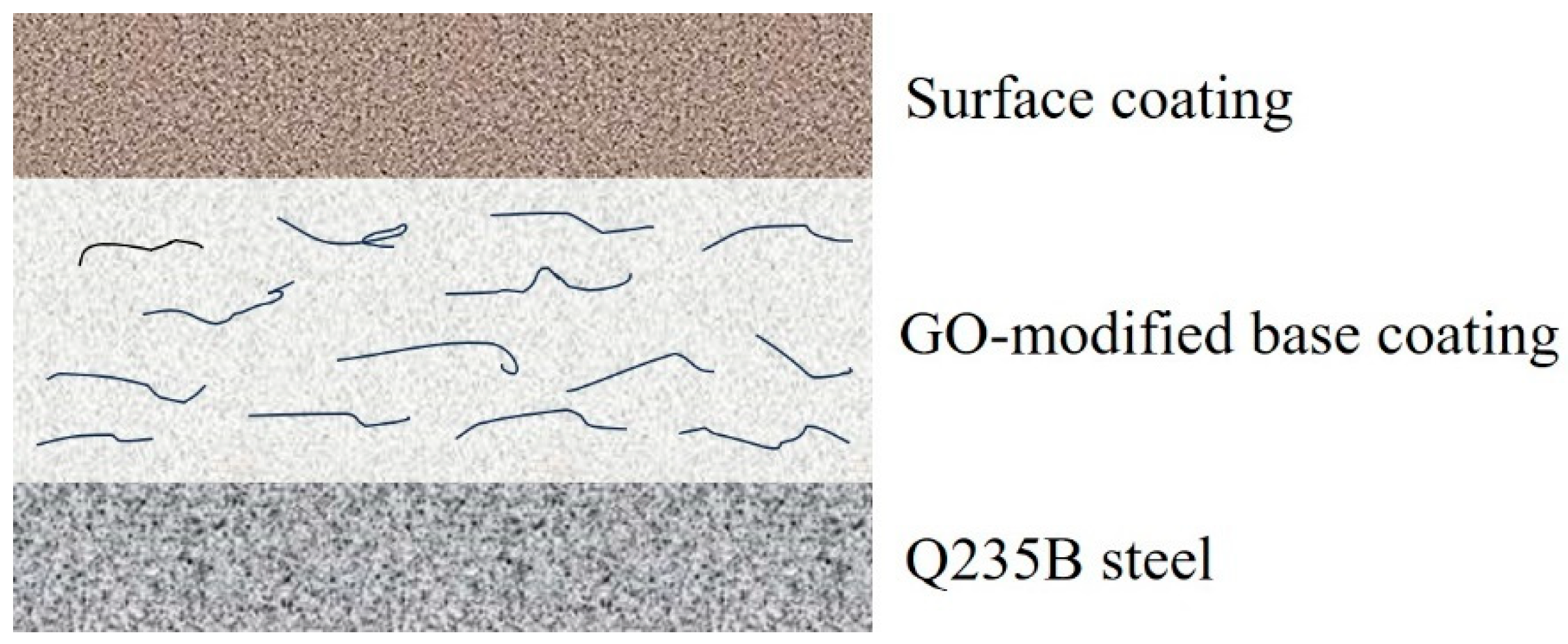

2.2. Structural Design and Raw Material Selection

2.3. Graphene Parameters

2.4. Microstructural Morphology Characterization

2.5. Full Immersion Test

2.6. Electrochemical Testing

2.6.1. Open Circuit Potential

2.6.2. Electrochemical Polarization Test

2.6.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

3. Experimental Results

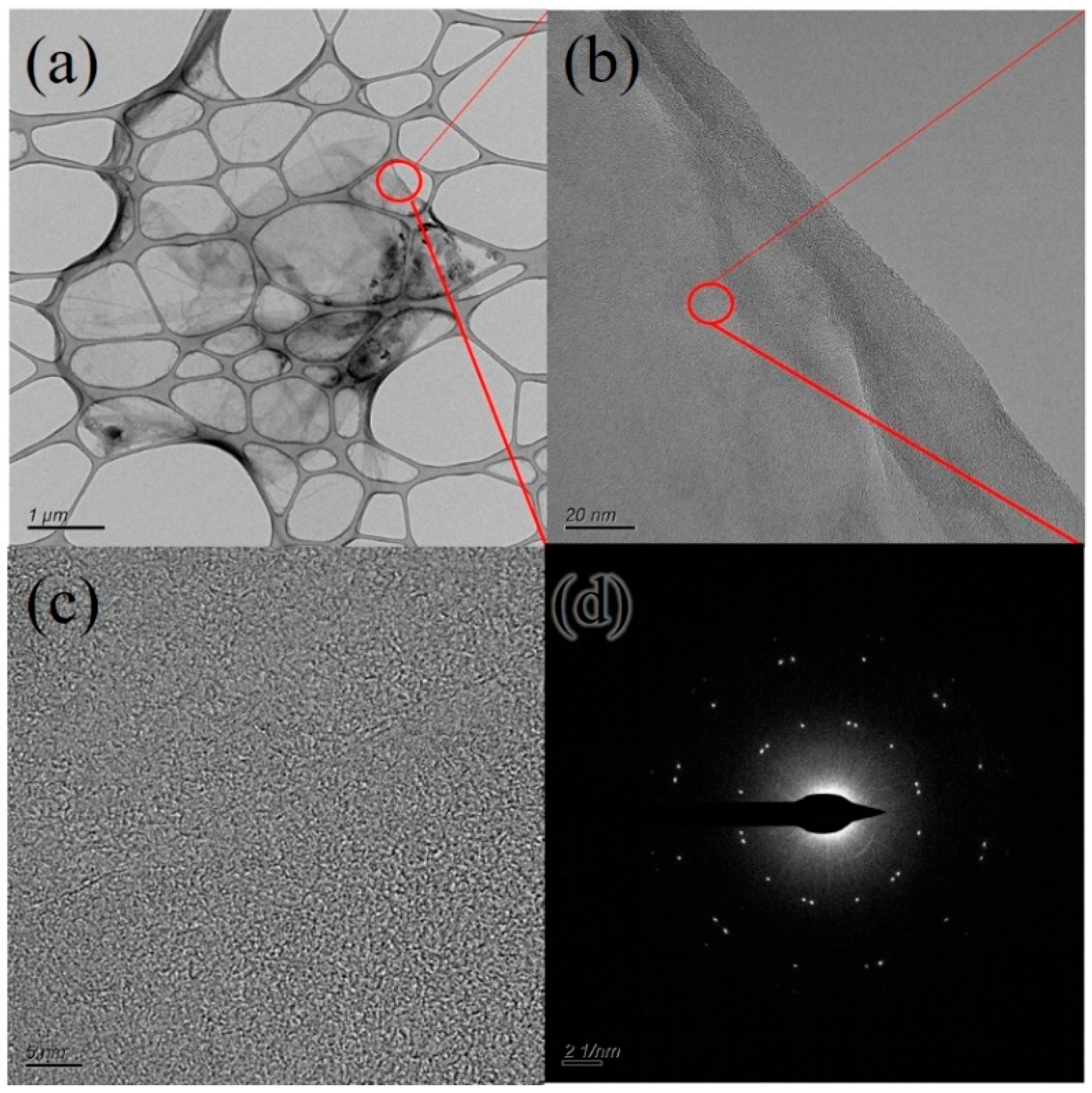

3.1. Microscopic Morphology and Composition of GO

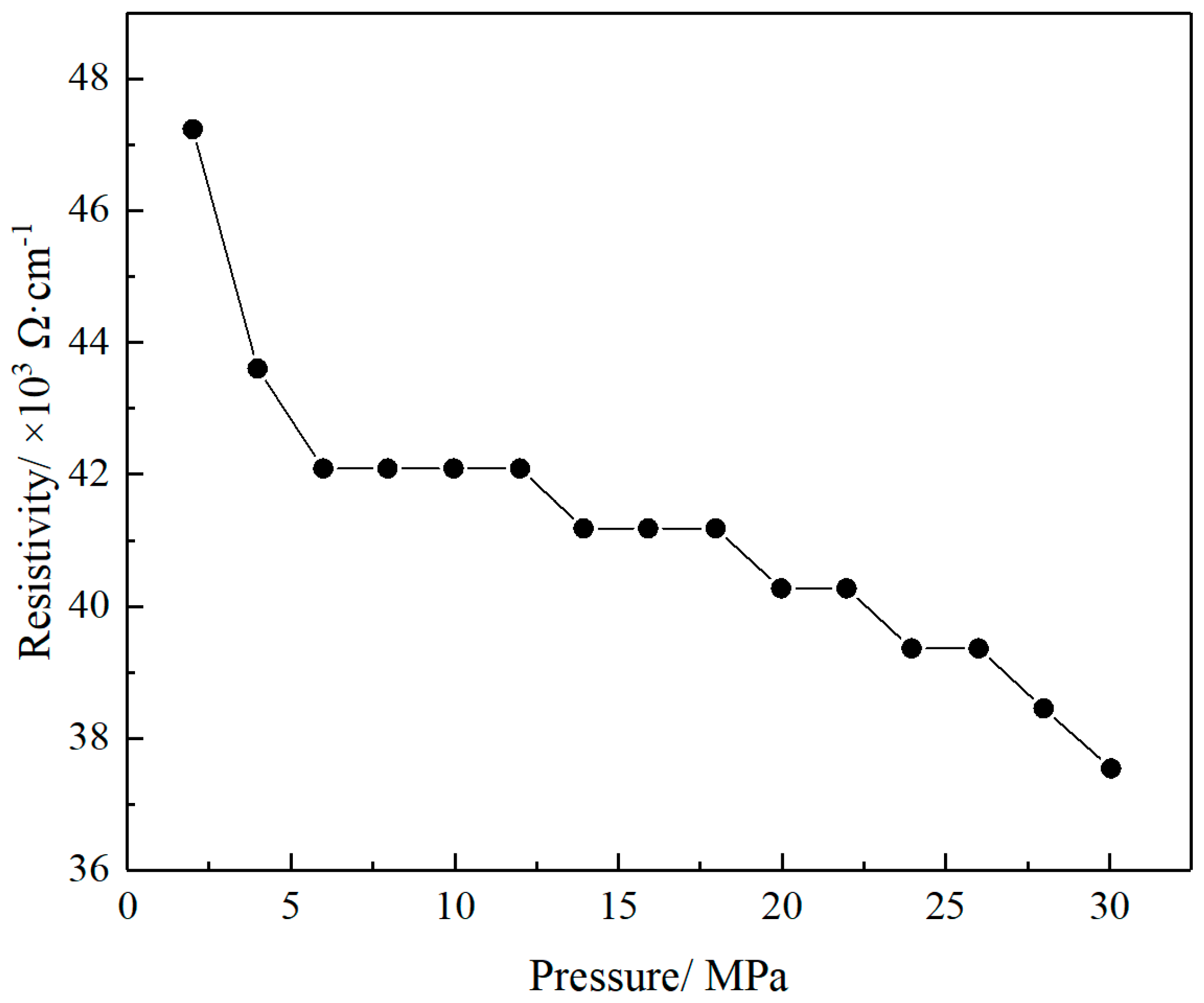

3.2. Resistivity of GO

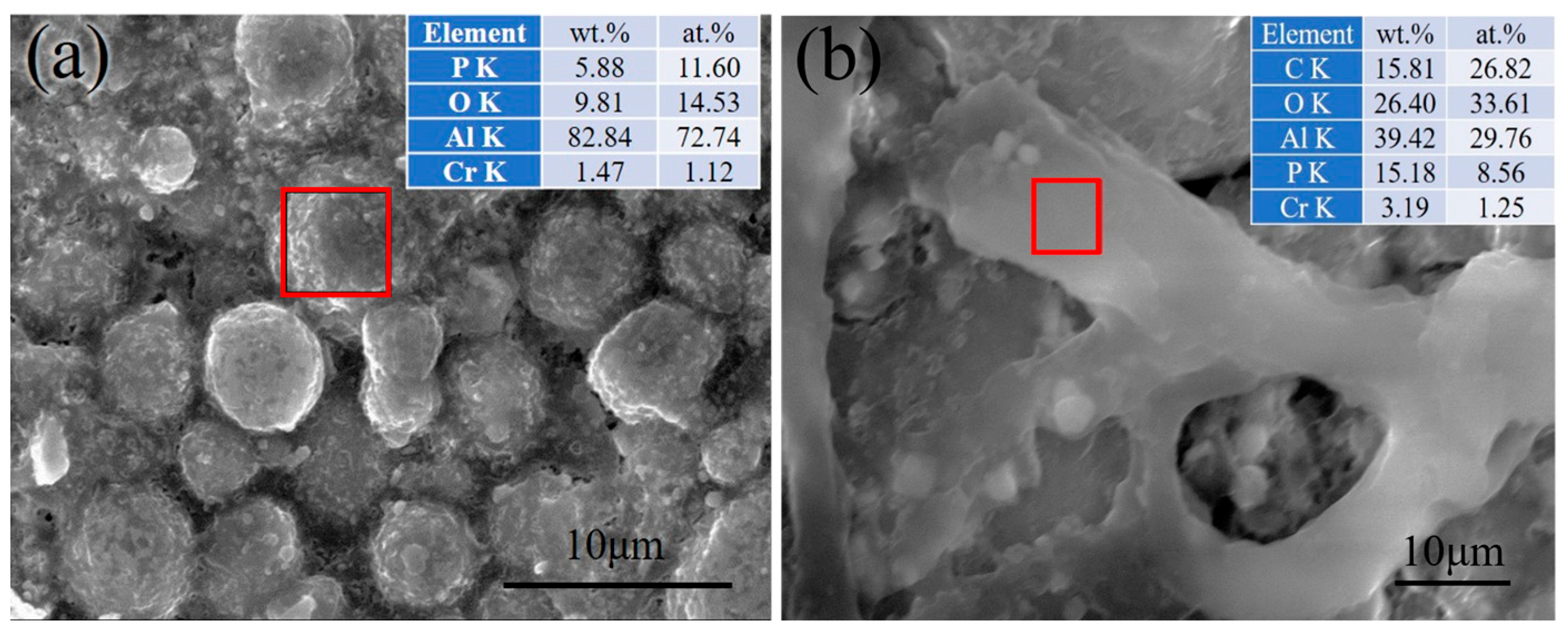

3.3. Characterization of the Coating

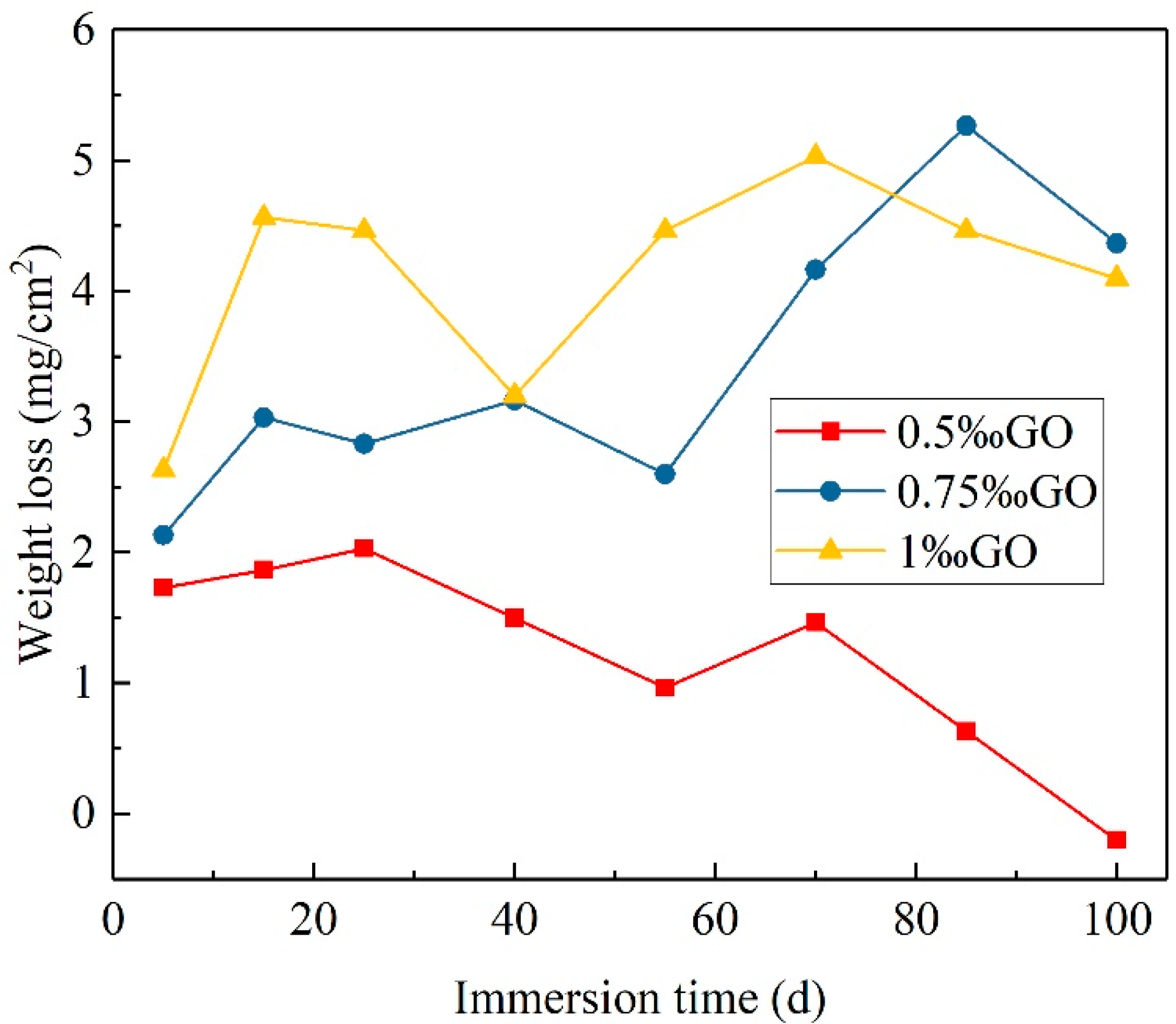

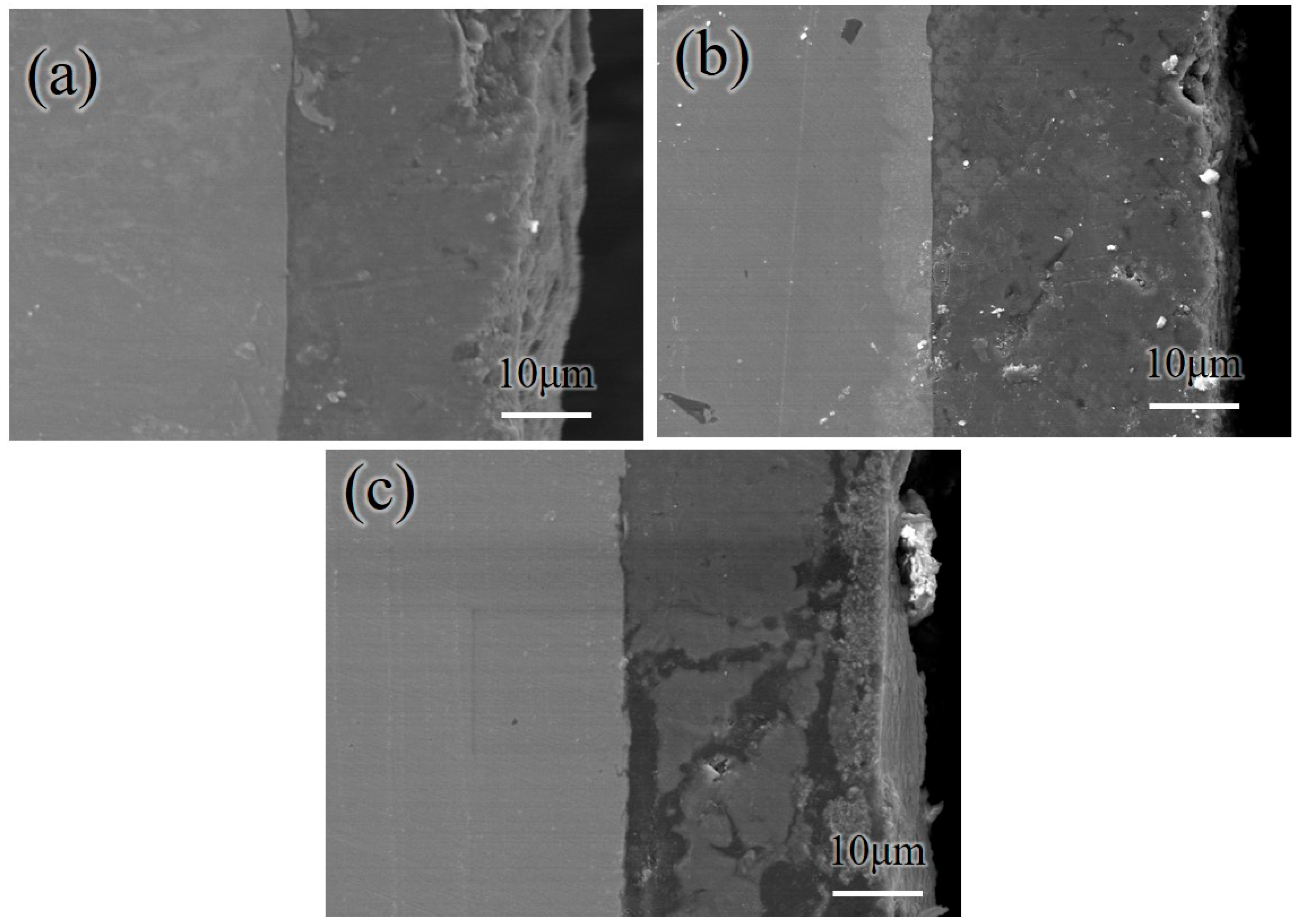

3.4. Full Immersion Test of GO-Modified WAP Coatings in 5% NaCl Solution

3.5. Electrochemical Testing of GO-Modified WAP Coatings in 3.5% NaCl Solution

3.5.1. OCP Variations in Three GO-Modified WAP Coatings

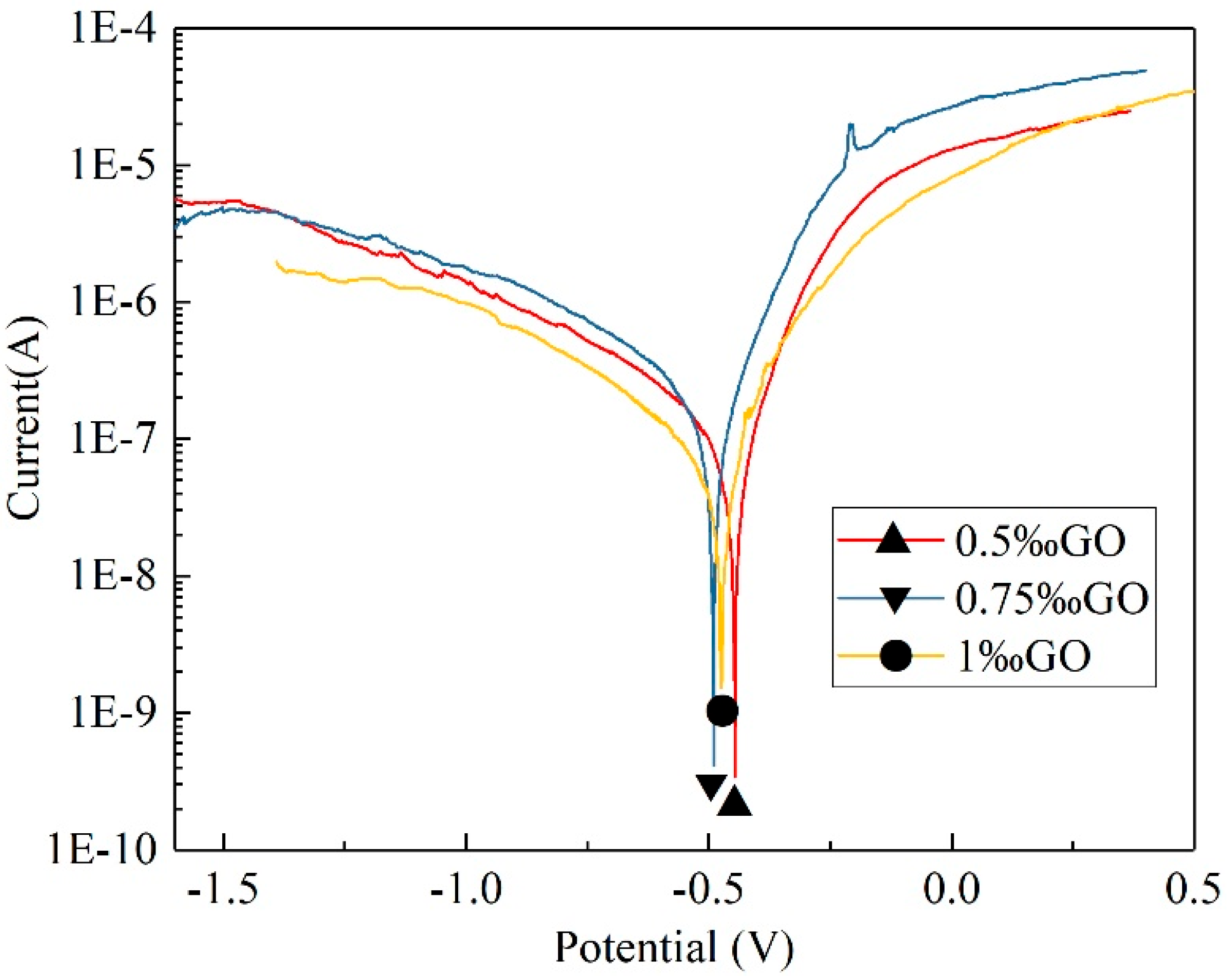

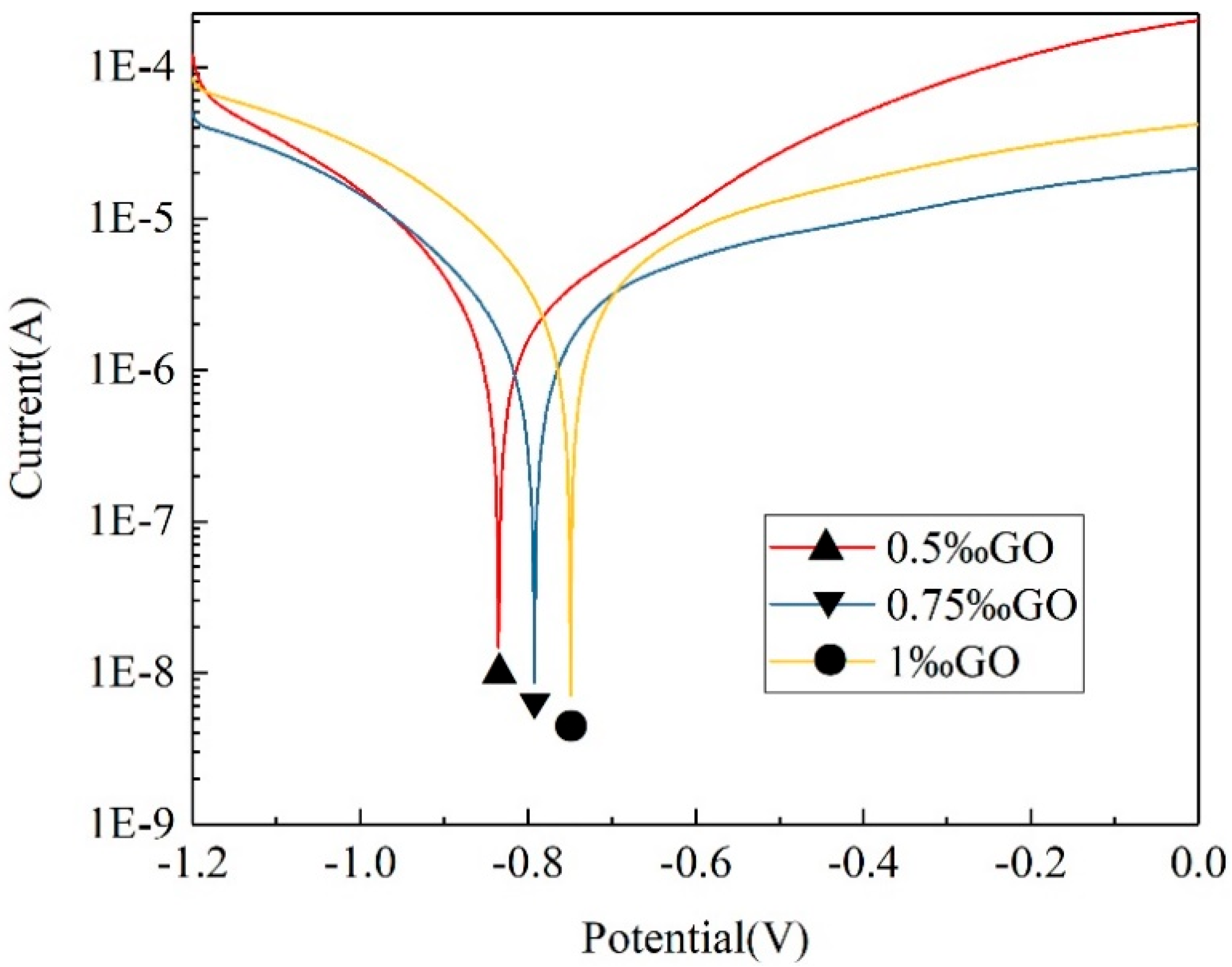

3.5.2. Polarization Test of GO-Modified WAP Coatings

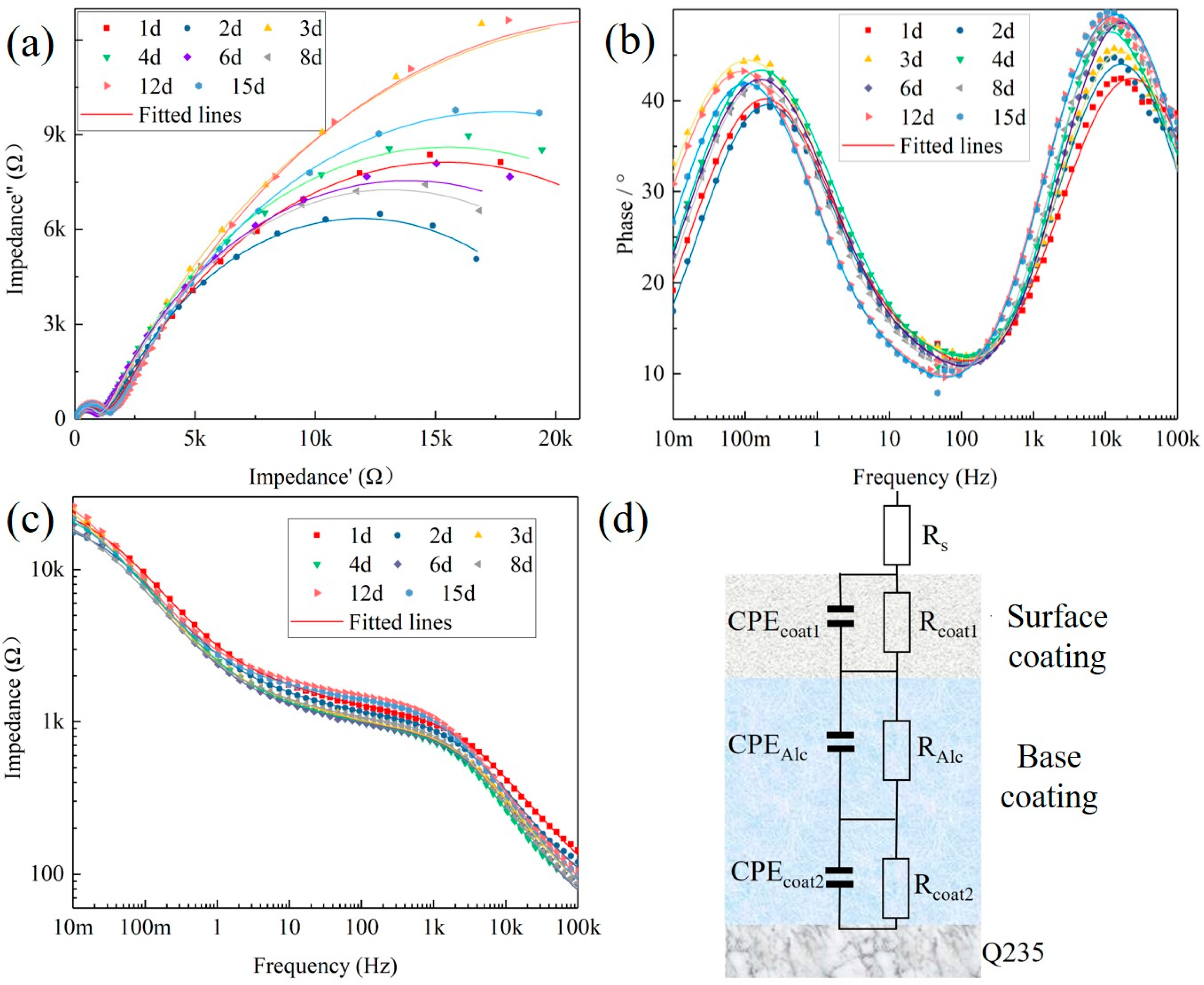

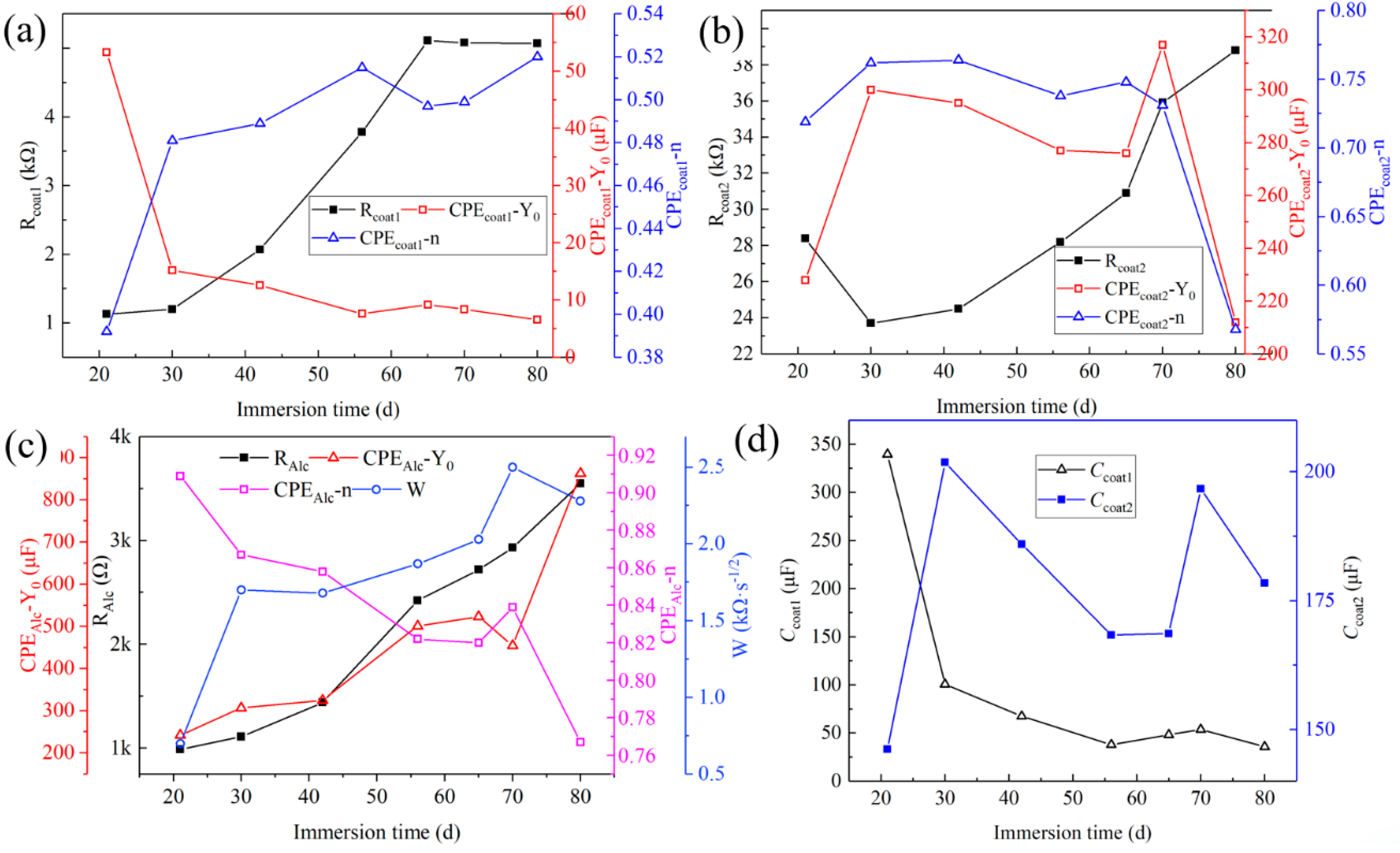

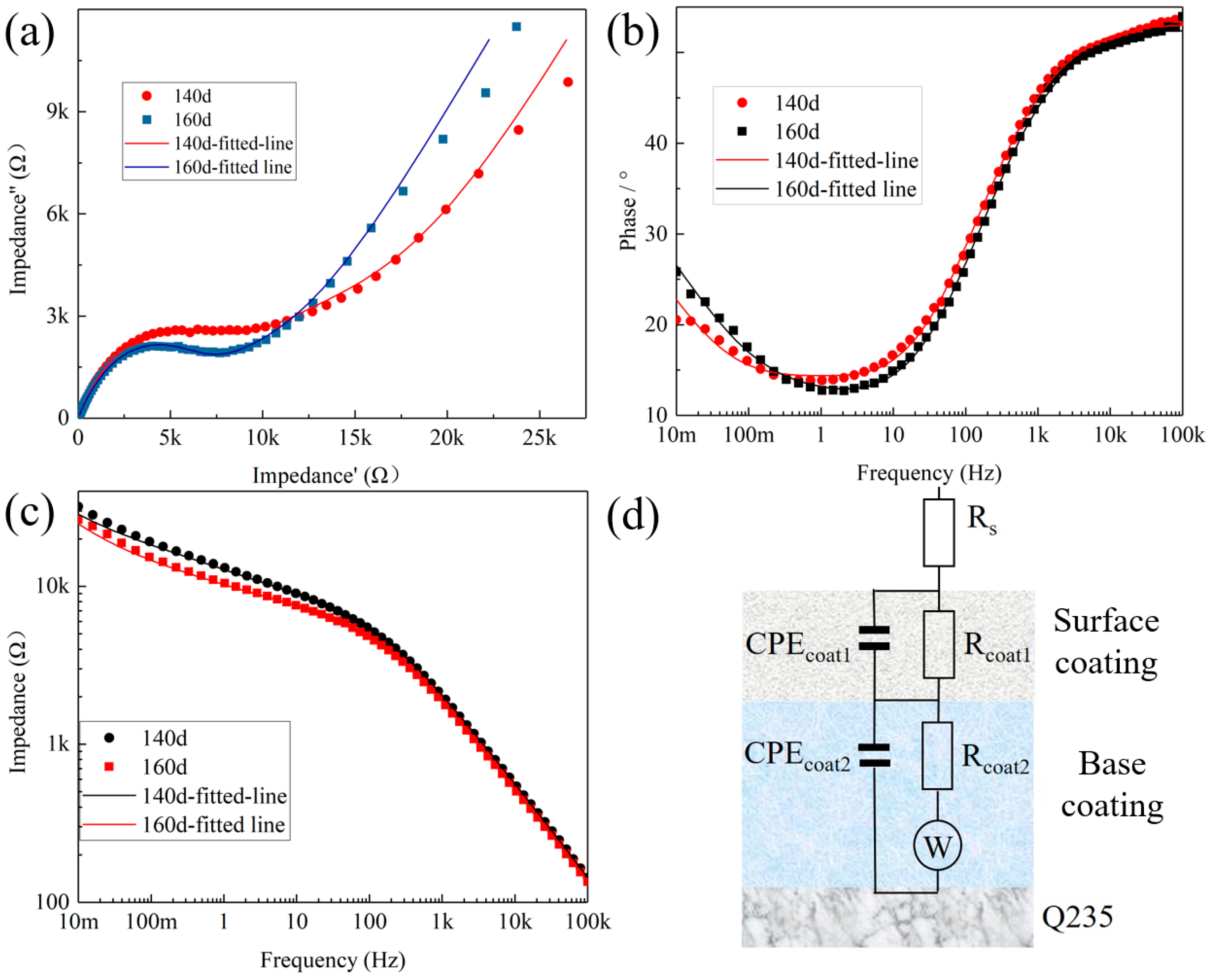

3.5.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Tests

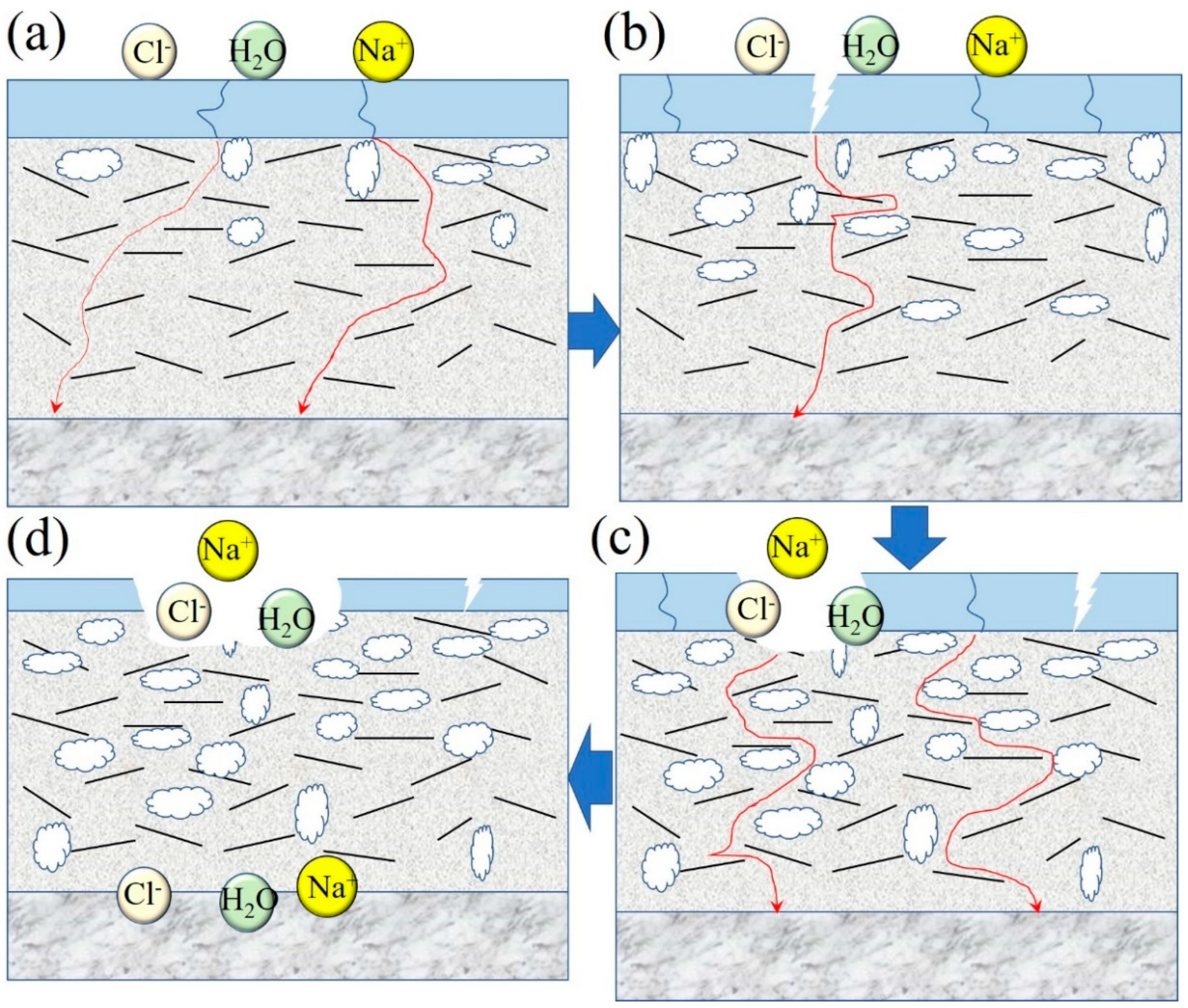

4. Analysis of Corrosion Resistance Mechanism

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adolfo, R.T.O.; Elsa Miriam, A.E.; Elizabeth, A.C.M.; Marisol, H.A.; Lucía, T.J. Evaluation of organic–inorganic coating on API steels. MRS Adv. 2025, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristen, B.; Justin, M. Two-Coat Inorganic Coating System for Steel Bridges. Transport. Res. Rec. 2025, 5, 914–923. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Chen, C.; Jiu, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. Effect of inorganic coating-modified steel reinforcement on properties of sulfoaluminate cement-based non-autoclaved aerated concrete slabs subjected to sodium chloride attack, sodium sulfate attack, and freeze-thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 469, 140484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.Y.; Han, H.J.; Ha, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, D. Development of Cr-free aluminum phosphate binders and their composite applications. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Naeem, H.T.; Li, J.; Kong, L.; Liu, J.; Shan, X.; Cui, X.; Xiong, T. A novel phosphate-ceramic coating for high temperature oxidation resistance of Ti65 alloys. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 23895–23901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhang, T.; Ahmed, S. Effects of Al:P stoichiometry and curing temperature on corrosion resistance of phosphate coatings. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 42069–42082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthanareeswari, M.; Kamaraj, P.; Tamilselvi, M.; Devikala, S. A low temperature nano TiO2 incorporated nano zinc phosphate coating on mild steel with enhanced corrosion resistance. Mater. Today-Proc. 2018, 5, 9012–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhang, L.; Lu, G.; Liu, M.; Liu, S. Anticorrosion mechanism of Al-modified phosphate ceramic coating in the high-temperature marine atmosphere. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 441, 128572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczka, K.; Grzmil, B.; Michalkiewicz, B.; Kowalczyk, K. Studies on obtaining of aluminium phosphates modified with ammonium, calcium and molybdenum. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 23, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, R.; Vakili, H.; Ramezanzadeh, B. Studying the effects of poly (vinyl) alcohol on the morphology and anti-corrosion performance of phosphate coating applied on steel surface. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. E 2016, 58, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, M.; Miao, X.; Bian, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y. Enhancing the corrosion and wear resistance of phosphate coatings with MXene-based self-healing fillers. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 261, 134–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bautin, V.A.; Bardin, I.V.; Kvaratskheliya, A.R.; Yashchuk, S.V.; Hristoforou, E.V. Effect of Graphene Oxide Addition on the Anticorrosion Properties of the Phosphate Coatings in Neutral and Acidic Aqueous Media. Materials 2022, 15, 6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Kumar, R.; Sahoo, B. Graphene Oxide Coatings on Amino Acid Modified Fe Surfaces for Corrosion Inhibition. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 3540–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Kumar, R.; Choudhary, H.K.; Sahoo, B. Graphene-oxide coating for corrosion protection of iron particles in saline water. Carbon 2018, 140, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.H.; Liu, C.L.; Han, D.J.; Ma, S.; Guo, W.; Cai, H.; Wang, X. Effect of graphene on corrosion resistance of waterborne inorganic zinc-rich coatings. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 774, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashish, B.; Swapnil, S.; Bhanvase, B.A.; Shende, P.G. Investigation on simultaneous enhancement in mechanical and anticorrosion performance of graphene oxide-zinc phosphate nanocomposite-based coatings. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 144, 110960. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wen, Z.; Wei, W.; Miao, X. Effect of Al2O3-MWCNTs on anti-corrosion behavior of inorganic phosphate coating in high-temperature marine environment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 473, 130039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Lv, H.; Yang, B. Research on High-Temperature Frictional Performance Optimization and Synergistic Effects of Phosphate-Based Composite Lubricating Coatings. Coatings 2025, 15, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A.; Patrik, S.; Fabio, E.F.; Joakim, R.; Rowena, C.; Ueli, A. Mechanism of zinc phosphate conversion coating formation on iron-based substrates. Corros. Sci. 2025, 248, 112796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JB/T 7901-1999; Metals materials-Uniform corrosion-Methods of laboratory immersion testing. National Machinery Industry Bureau: Bengjing, China, 1999.

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, Y. An in-depth study of photocathodic protection of SS304 steel by electrodeposited layers of ZnO nanoparticles. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2020, 399, 126158. [Google Scholar]

- Strebl, M.G.; Bruns, M.P.; Virtanen, S. Respirometric in Situ Methods for Real-Time Monitoring of Corrosion Rates: Part III. Deconvolution of Electrochemical Polarization Curves. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ji, Y.; Xu, Z. Corrosion behavior of reinforcing bar in magnesium phosphate cement based on polarization curve. Sādhanā 2020, 45, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tato, W.; Landolt, D. Electrochemical Determination of the Porosity of Single and Duplex PVD Coatings of Titanium and Titanium Nitride on Brass. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 145, 4173–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bi, Q.; Leyland, A.; Matthews, A. An electrochemical impedance spectroscopy study of the corrosion behaviour of PVD coated steels in 0.5 N NaCl aqueous solution: Part I. Establishment of equivalent circuits for EIS data modelling. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, S.; Li, Z.; Hou, S. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Evaluation of Corrosion Protection of X65 Carbon Steel by Halloysite Nanotube-Filled Epoxy Composite Coatings in 3.5% NaCl Solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2019, 14, 4659–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelina, M.L.; Dennis, V.T.; Jean, R.C.L. About the Electrochemical Mechanism of Aluminum Corrosion in Acid Media by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Mater. Corros. 2025, 76, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, L.; Silipigni, L.; Cutroneo, M.; Torrisi, A. Graphene oxide as a radiation sensitive material for XPS dosimetry. Vacuum 2020, 173, 109175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, C.; Stefano, R.; Flavio, D.; Michele, F. Exploring the role of passivating conversion coatings in enhancing the durability of organic-coated steel against filiform corrosion using an electrochemical simulated approach. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 189, 108357. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, T.; Mark, E.O. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Meroufel, A.; Touzain, S. EIS characterisation of new zinc-rich powder coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2007, 59, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.G.; Gong, G.P.; Yan, C.W. EIS study of corrosion behaviour of organic coating/Dacromet composite systems. Electrochim. Acta 2005, 50, 3320–3332. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Fu, J.; Hu, Y.; Liang, J.; Li, J.; Xu, W. The design of oxidation resistant Ni superalloys for additive manufacturing. Addit Manuf. 2025, 97, 104616. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Ning, C.; Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Cai, Z. Comparison of surface integrity, microstructure and corrosion resistance of Zr-4 alloy with various laser shock peening treatments. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2025, 498, 131799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Ma, G.; Lu, Y.; Wei, A.; Yang, C.; Huang, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, H. Tribocorrosion behaviours and mechanisms of Inconel 625–nano/micro Al2O3 composite coatings prepared by plasma enhanced high-velocity arc spraying. Corros. Sci. 2025, 256, 113221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| C | Si | Mn | S | P | Fe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q235B | 0.12~0.20 | ≤0.30 | 0.30~0.70 | ≤0.045 | ≤0.045 | Rest |

| Chemical Composition | Property | Manufacturer | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al(H2PO4)3 | 30% aqueous solution | Shenyang Shisan Biochemical Technology Development Co., Ltd. (Shenyang, China) | 20 g |

| ZnO | AR | Haitai Nanomaterials Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) | 0.1 g |

| MgO | AR | Nanjing Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) | 0.3 g |

| Al2O3 | 3000 mesh | Beijing Deke Daojin Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) | 5 g |

| MgCrO4 | AR | Jiangsu Yonghua Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China) | 1 g |

| Al | 3000 mesh | Beijing Deke Daojin Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) | 20 g |

| Aqua destillata | \ | Self-made | 15 g |

| Promoter | \ | Self-made | 0.5 g |

| Chemical Composition | Property | Manufacturer | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al(H2PO4)3 | 30% aqueous solution | Shenyang Shisan Biochemical Technology Development Co., Ltd. | 30 g |

| MgO | AR | Nanjing Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. | 0.4 g |

| Al2O3 | 3000 mesh | Beijing Deke Daojin Science and Technology Co., Ltd. | 5 g |

| MgCrO4 | AR | Jiangsu Yonghua Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. | 1 g |

| Cr2O3 | 99.95% | Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) | 10 g |

| CMC | 800~1200 mPa·s | Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. | 0.2 g |

| PMA | 99% | Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. | 5 g |

| aqua destillata | \ | Self-made | 10 g |

| promoter | \ | Self-made | 1 g |

| Name | Preparation Method | Purity | BET (m2·g−1) | Layer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO | freeze-drying | ≥99% | 1200~1500 | single |

| GO | βc Mv·dec−1 | βa mV·dec−1 | icorr μA·cm−2 | Ecorr mV | Rp kΩ·cm−2 | PE % | P % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5‰ | −868 | 556 | 1.88 | −476 | 78.4 | 89.36 | 1.3 |

| 0.75‰ | −1080 | 365 | 0.599 | −490 | 197 | 96.61 | 0.3 |

| 1‰ | −1600 | 462 | 0.471 | −474 | 331 | 97.33 | 0.2 |

| GO Content | βc mV·dec−1 | βa mV·dec−1 | icorr μA·cm−2 | Ecorr mV | Rp kΩ·cm−2 | PE % | P % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5‰ | −285 | 441 | 4.2 | −835 | 17.9 | 68.48 | 2.9 |

| 0.75‰ | −389 | 1190 | 4.9 | −792 | 26 | 72.27 | 4.6 |

| 1‰ | −470 | 1100 | 9.49 | −749 | 15.1 | 46.3 | 8.4 |

| Immersion Time | Rs mΩ | R1 kΩ | Q1-Y0 μF | Q1-n \ | R2 kΩ | Q2-Y0 μF | Q2-n \ | W kΩ·s−1/2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140d | 59 | 7.62 | 2.03 | 628 | 14.3 | 49.4 | 0.482 | 4.59 |

| 160d | 94.8 | 6.47 | 2.13 | 628 | 10.2 | 69.1 | 0.458 | 5.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, F.; Xu, J.; Wei, X.; Cao, J.; Wu, H.; Bai, L.; Ma, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; You, J.; et al. Enhanced Corrosion Resistance of Water-Based Aluminum Phosphate Coatings via Graphene Oxide Modification: Mechanisms and Long-Term Performance. Coatings 2026, 16, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010011

Ding F, Xu J, Wei X, Cao J, Wu H, Bai L, Ma Y, Li D, Wang Y, You J, et al. Enhanced Corrosion Resistance of Water-Based Aluminum Phosphate Coatings via Graphene Oxide Modification: Mechanisms and Long-Term Performance. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Feng, Jiahui Xu, Xiaoxin Wei, Jiangdong Cao, Hongyan Wu, Lang Bai, Yujie Ma, Dongqian Li, Yilin Wang, Jiahan You, and et al. 2026. "Enhanced Corrosion Resistance of Water-Based Aluminum Phosphate Coatings via Graphene Oxide Modification: Mechanisms and Long-Term Performance" Coatings 16, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010011

APA StyleDing, F., Xu, J., Wei, X., Cao, J., Wu, H., Bai, L., Ma, Y., Li, D., Wang, Y., You, J., & Jiang, B. (2026). Enhanced Corrosion Resistance of Water-Based Aluminum Phosphate Coatings via Graphene Oxide Modification: Mechanisms and Long-Term Performance. Coatings, 16(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010011