1. Introduction

In order to address the global water scarcity issue, it is advisable to implement a strategy that involves the reuse of wastewater from industrial processes in various domestic activities, such as cleaning and storm drainage [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Industrial wastewater discharge represents a substantial potential for the recovery and reuse of valuable effluents. This is of the utmost importance because the industry can invest in greater water efficiency, recycling, and management to protect and preserve the water used in its processes. Wastewater is known to contain various impurities, such as pesticides, fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, oils, detergents, and dyes. Hazardous waste, particularly when containing harmful chemicals such as heavy metals and/or dyes, can pose a significant threat to soil and living beings. Consequently, special treatment is required before discharging effluent into aquifers. In some cases, untreated wastewater is released into valleys, rivers, or lakes, which has had a significant negative impact on the aquifer environment [

5,

6,

7].

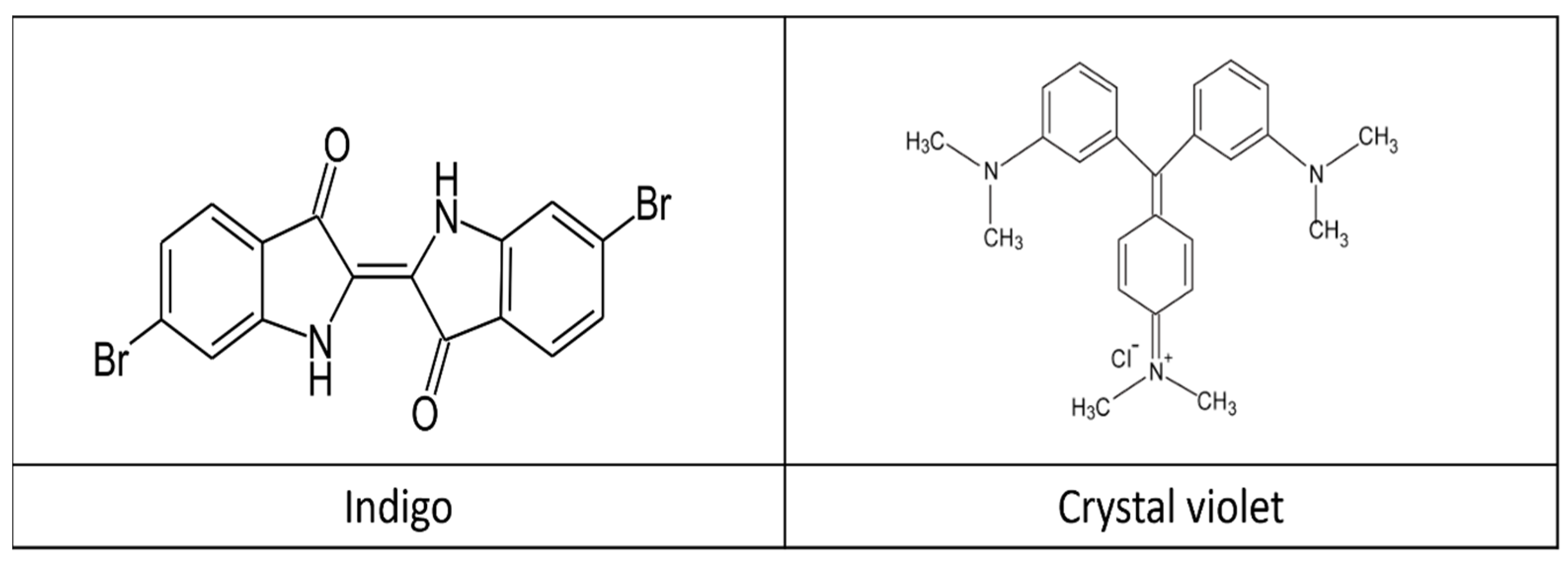

On the other hand, there are approximately 10,000 types of dyes utilized as dyeing agents, predominantly in the textile industry. The release of dyes into natural environments is a concern due to their high persistence, toxicity, and potential for bioaccumulation in living organisms [

8]. One of the most widely used dyes is indigo, which is produced in large quantities worldwide. This dye is used to color jeans and other denim textiles [

9]. Indigo dye can be obtained from natural and synthetic sources, and these commercial formulations may have different compositions and impurities [

10]. One potential drawback of this dye is its toxicity. This property has been the subject of scientific study, with researchers evaluating its impact on aquatic organisms [

11]. Another dye, such as crystal violet (CV), also known as methyl violet or gentian violet, is a water-soluble chemical compound belonging to the family of triphenylmethane cationic dyes. Also, inhalation of CV has been found to cause carcinogenic effects, pain, congestion, and irritation of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract in living beings [

12,

13]. A variety of strategies have been employed by multiple authors to successfully remove this dye from dyed textiles. However, adsorption emerged as a highly cost-effective approach for treating textile effluents. The use of numerous adsorbents for CV dye removal has been described, including natural clay minerals, fly ash, plant biomass, activated carbon, 3D graphene nanocomposites, and solvent-treated black locust bark [

14]. The chemical structure of these dyes is presented in

Figure 1.

In recent years, various water treatment techniques have been investigated for the removal of dyes from aqueous media. These techniques include coagulation, membrane filtration, flocculation, and adsorption [

15]. The adsorption technique is a promising wastewater treatment method due to its low cost, high efficiency, ease of use, and safety. [

16].

Certain polymers possess adsorbent properties and are used in film form. Polysulfone (PSF) is a material of choice for engineering applications and the manufacture of devices that require high stress and high resistance due to its excellent thermal stability properties, good mechanical performance, and, in particular, its biocompatibility. These properties can be improved by incorporating nanoparticles with photocatalytic, antibacterial, and adsorption properties to produce a polymeric nanocomposite [

17].

Zinc oxide (ZnO) nanomaterials offer several advantages, including good chemical and physical stability, non-toxicity, and high photocatalytic activity. The photocatalytic activity of ZnO depends on the band gap and the UV light or visible light irradiation. The electron and hole can interact with the O

2 adsorbed on the surface of the photocatalyst and H

2O to generate O

2− and ·OH, respectively, which can reduce and oxidize the organic contaminants completely into their respective end products (CO

2 and H

2O, respectively). Furthermore, ZnO nanoparticles possess a notable property of high antibacterial activity [

18]. These nanoparticles can undergo chemical modification with organic molecules to enhance their properties and improve compatibility with the polymer. Some of the nanoparticle-modifying compounds can be amino acids, such as L-serine, an organic molecule that can interact with the polymer and, in turn, act as a dye adsorbent [

19]. L-serine is a polar amino acid that is considered a renewable reagent. It has three functional groups: an amino group, a hydroxyl group, and a carbonyl group, which can bond with ZnO nanoparticles through electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonds. This modification will stabilize the ZnO to be stable in solutions, prevent agglomeration, and ensure compatibility with polysulfone. Depending on the nature of the organic molecules, there are different techniques for surface chemical modification, such as conventional heating, microwaves, plasma, and ultrasound. These last three techniques are considered green chemistry techniques because they do not generate reaction byproducts during the reaction and optimize reagent consumption. As a result, they are considered environmentally friendly surface activation energies.

In this study, ultrasound was selected as the method for modifying the nanoparticles and obtaining the films. It is also known that the use of ultrasound helps activate chemical bonds and promote faster modification through sonochemistry, which has an unconventional energy source used to agitate particles in solution. In liquid systems, it has been explained that the chemical and physical effects of ultrasound are a consequence of the phenomenon of acoustic cavitation. Acoustic cavitation occurs in response to a decrease in pressure due to the propagation of an acoustic wave [

20]. Andrade et al., 2025, used the ultrasound method for the synthesis of polysulfone and carbon black for application in the adsorption of uremic toxins [

17]. Likewise, Muhulet et al. 2020 developed composite polymeric membranes based on polysulfone and carbon nanotubes decorated with titanium dioxide by the sonochemical method; these membranes can be used in photooxidative degradation of pollutants [

21]. Alves de Sousa et al., 2024, investigated the effect of ZnO concentrations from 0 to 3% on a polysulfone membrane. The membranes were used in the removal of a textile dye, and the best results were obtained with the membrane at a 3% ZnO concentration [

22]. Hidayah et al., 2022, studied oil refinery water treatment using polysulfone membrane ZnO nano composites modified with ultraviolet irradiation and polyvinyl alcohol. This membrane was prepared using the dry/wet phase inversion method. The best results were with the membrane containing 19 wt% of polysulfone, 1 wt% nano ZnO, 1 min of UV, and 3 wt% of polyvinyl alcohol [

23]. Zamani et al. 2023 they fabricated a polysulfone and ZnO membrane using the same method. This membrane was applied for salt rejection. The rejection rate of the simple polysulfone membrane was 92.5%, a percentage that increased to 97.21% with the addition of zinc oxide nanoparticles to the polymer matrix [

24].

Most studies of nanocomposite-based films focus solely on the incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles without chemical modification. The application of sonochemistry is a method that has received minimal attention in the literature. The adsorption properties of indigo and crystal violet on this novel film based on a polysulfone nanocomposite with L-serine-modified ZnO are unknown. This study will expand knowledge about new polysulfone-based films with L-serine-modified ZnO nanoparticles.

The objective of this study is to synthesize films based on polysulfone with chemically modified ZnO nanoparticles by the sonochemical method for application as an adsorbent material for indigo and crystal violet dyes. The authors hypothesize that polysulfone/ZnO films modified with L-serine enhance the adsorption capacity of organic dyes (indigo and crystal violet) due to the enhanced surface affinity of the hydroxyl groups of ZnO and the functional groups of L-serine, which promote interaction between the polymer matrix and the ZnO nanoparticles and the dye molecules.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The nanoparticles ZnO (<100 nm) from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA), Polysulfone (Sigma Aldrich), L-serine from Sigma Aldrich(St. Louis, MI, USA), chloroform, crystal violet from Jalmek (San Nicolás de los Garza, Nuevo Leon, México), indigo from FagaLab (Sinaloa, México), and distilled water with a pH of 7 were used as a solvent to obtain the aqueous solutions.

2.2. Modification of ZnO

50 mL of deionized water was added to a beaker, and 10 g of L-serine were dispersed in an ultrasonic bath for 15 min.

Next, 2.5 g of ZnO nanoparticles were weighed and added 10 mL of deionized water, which was then used as a solvent to obtain the aqueous solutions. The samples were then placed in the ultrasonic bath for 15 min. ZnO:L-serine molar ratio is 4:1. The two solutions were subsequently mixed and ultrasonicated using a variable-frequency ultrasonic probe (15 to 50 kHz) for a duration of 60 min. at a temperature of 40 °C. Thereafter, the solution was subjected to a constant temperature of 80 °C for a period of 3 h, followed by filtration and washing with deionized water. The solution was subsequently dried at a temperature of 80 °C for a period of two hours.

2.3. Preparation of Films

Mixed in solution: Polysulfone and modified ZnO films were prepared by solution mixing. The ZnO particles were dispersed in 10 mL of chloroform using an ultrasonic bath (BRANSON, Brookfield, CT, USA), operating at 40 kHz and 220 V, for a duration of 5 min at a temperature of 40 °C. The polysulfone pellets were then dispersed in 40 mL of chloroform for 10 min. The ZnO solution was added to the polysulfone solution, yielding a final volume of 50 mL. The mixture was then subjected to 30 min of ultrasonication.

2.4. Characterization

The FT-IR spectra of the films were recorded on a Magna Nicolet 550 spectrometer (Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a diamond attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory (Waltham, MA, USA). Measurements were conducted within the range of 400–4000 cm−1.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), was performed using a Discovery TGA 5500 (TA Instruments Inc., New Castle, PA, USA). The samples were heated from 25 to 700 °C under an N2 atmosphere at a flow rate of 50 mL/min and a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The mass loss and thermal decomposition temperature were measured and reported as a function of temperature.

The XRD patterns of polysulfone/ZnO were recorded at room temperature using the X-ray D8 Advance Eco Bruker diffractometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) with a scan speed of 1 min−1. The diffraction angle (2θ) was varied from 10 to 80° at a step size of 0.02, with operating conditions of 40 kV and 40 mA.

The morphology of the polysulfone/ZnO Film was determined using a scanning electron microscope SEM, JEOL JCM 6000 (Jeol LTD., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan); with a palladium-gold, sputter coating of 5 kV.

Table 1 shows the concentrations of the samples obtained for this study.

2.5. Batch Adsorption Experiment

The experimental conditions were selected based on preliminary tests and literature [

16,

19]. Firstly, dye stock solutions 100 ppm. Indigo or crystal violet was prepared. Then, 100 mL of dye solutions from stock solutions were placed in flasks. Then, 20 mg of Polysulfone/ZnO film (divided into portions of 1 cm × 1 cm) was added to each dye solution. The flasks were agitated at 100 rpm. The dye concentration was determined by a spectrophotometer Duetta, Horiba Scientific (Horiba Reno Technology Center, Reno, NE, USA) at 450 and 590 nm for the indigo and crystal violet, respectively. The pH used for the indigo dye was pH 2, and that of the crystal violet was pH 5 is adjusted with HCl (0.1 M) or NaOH (0.1 M). All experiments were conducted at a temperature of 25 °C. Our preliminary results indicated that 80 min is enough for the sorption to reach equilibrium, but for practical reasons, the adsorption experiments are run up to 120 min.

All data in this study are the average of triplicate samples. Relative errors in all cases are displayed in the graphs with error bars. The equilibrium adsorption capacity (q

e) was determined by Equations (1) and (2):

where Ci and Ce are the initial and equilibrium indigo and crystal violet dye (mg) concentrations. V and m are the volume of dye solution and the amount of adsorbent (g).

where Ci and Ce are initial and final concentrations, respectively.

Adsorption isotherms

Langmuir

The isotherm refers to homogeneous adsorption. The mathematical equation for the Langmuir isotherm can be represented as Equation (3):

qe (mg/g) and Ce (mg/L) are the concentrations of the solid phase and liquid phase of the adsorbate in equilibrium, respectively; qm is the maximum adsorption capacity, and KLqm is the constant obtained from plotting Ce/Qe versus Ce.

Freundlich

The Freundlich isotherm is one of the most widely used adsorption equilibrium models, started on empirical grounds but was later shown to be thermodynamically rigorous for adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces. Equation (4) can be represented as follows:

K

F (mg/g) (L/mg) and 1/n are the Freundlich constants related to the adsorption capacity, and n is the heterogeneity calculated with the linear plot of Ln(q

e) versus Ln(C

e).

Adsorption kinetics

Also, equations used are pseudo first-order and pseudo second-order equations, which describe physisorption and chemisorption, respectively.

Pseudo second-order:

where k and k1 are pseudo first-order and second-order rate constants

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

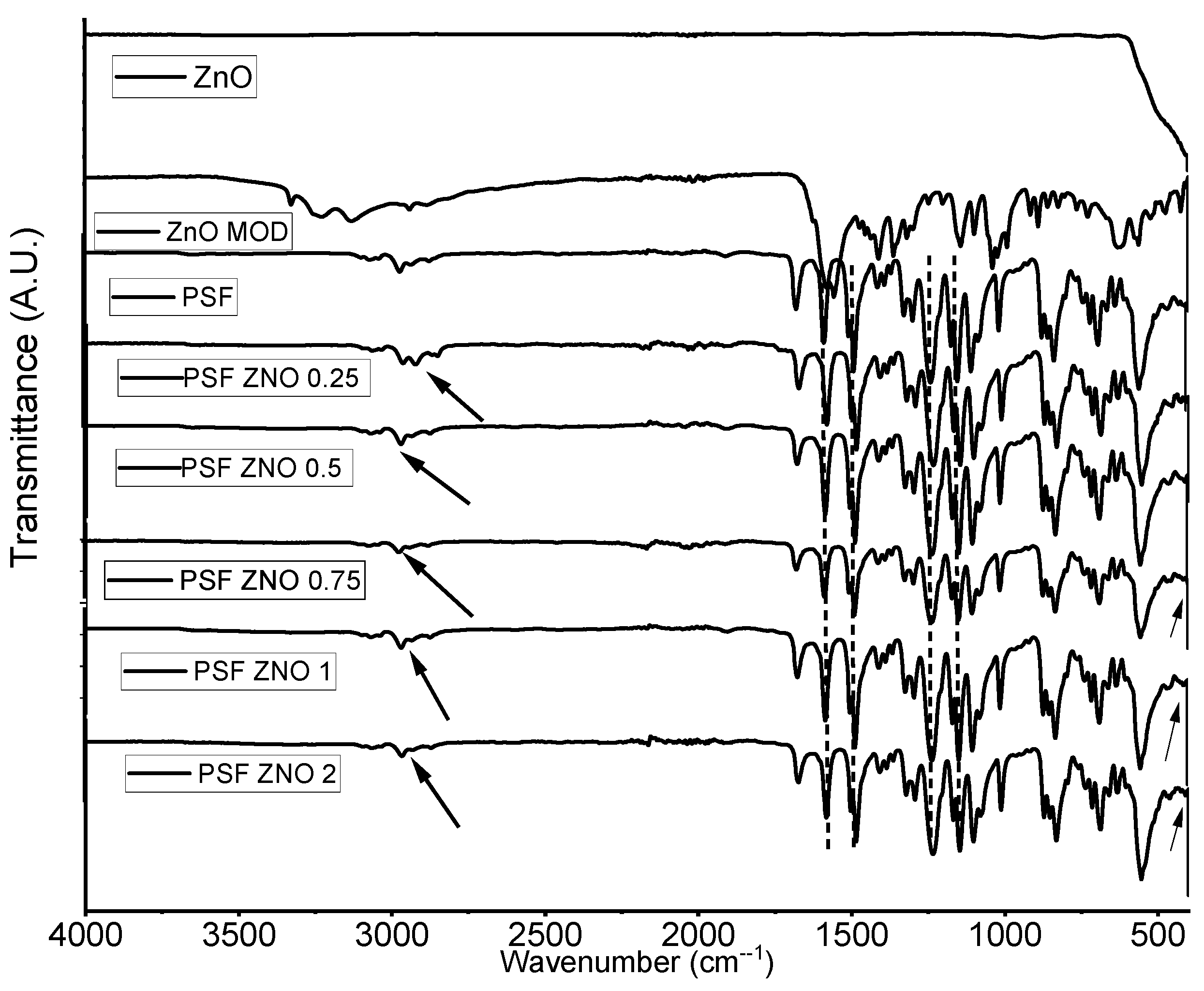

Figure 2 shows the FTIR spectra of ZnO, ZnO MOD, pure polysulfone polymer, and nanocomposites obtained by solution mixing. In pure ZnO, only one signal could be observed at 492 cm

−1, corresponding to the Zn-O bond signal [

17].

The FT-IR analysis of ZnO MOD presents signals corresponding to L-serine, at 1038 cm

−1, where a signal attributed to the stretching of the C–N bond is observed, at 1560 cm

−1, a signal corresponding to the stretching vibration of the carbon-hydrogen (C–H) bond appears and at 3330 cm

−1, the stretching vibration of N–H, finally, at 3127 cm

−1 a signal that may be due to the stretching vibration of the O–H bond [

24].

In the pure polysulfone polymer, a small signal is visible at 2968 cm

−1, attributed to the symmetric stretching of –CH

3. The characteristic signals of the aromatic rings of polysulfone were also found at 1583 and 1487 cm

−1. Additionally, at 1233 and 1146 cm

−1, asymmetric and symmetric stretching bands of the sulfone group are shown [

25].

For the nanocomposites of polysulfone and modified ZnO at different concentrations, we can observe signals corresponding to the polysulfone polymer at 1583 and 1487 cm−1, characteristic signals of the aromatic rings, and at 1233 and 1147 cm−1 of asymmetric and symmetric stretching of the sulfone group.

In addition, in the nanocomposites with PSFZNO0.25, PSFZNO0.5, and PSFZNO1, a signal was detected at approximately 2864 cm

−1 and 2919 cm

−1, which could be associated with the O–H bond stretching vibration and the stretching vibration of the C–H bond of L-serine [

26].

In addition, in the nanocomposites with PSFZNO0.25, PSFZNO0.5, and PSFZNO1, a signal was detected at approximately 2864 cm

−1 and 2919 cm

−1, which could be related to the characteristic for vibrations of the CH

3 groups of polysulfone and the stretching vibration of the C–H bond of L-serine [

27].

As shown in

Table 2, the signals obtained for the nanoparticles, polymers, and films of the materials are listed.

In the FTIR spectrum, we can also observe that for polysulfone alone, the signals that appear at 1233 and 1147 cm−1, corresponding to the sulfonated groups, decrease in intensity for the compound with more modified particles (PSF ZNO 2). This may be due to the chemical interaction between the polysulfone polymer matrix and the ZnO modified with L-serine.

Due to the good homogeneity in the dispersion of the modified nanoparticles in the matrix, no significant changes are seen in the nanocomposites obtained by the FTIR technique. This has already been reported by Andrade Guel et al. 2025, when preparing nanocomposites of polysulfone and carbon black-modified by melt extrusion and solution mixing [

17].

It is expected that having L-serine-modified particles in the polymer matrix will lead to greater interaction with the organic dye molecules, producing chemical bonds that allow the traction of these contaminants.

3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

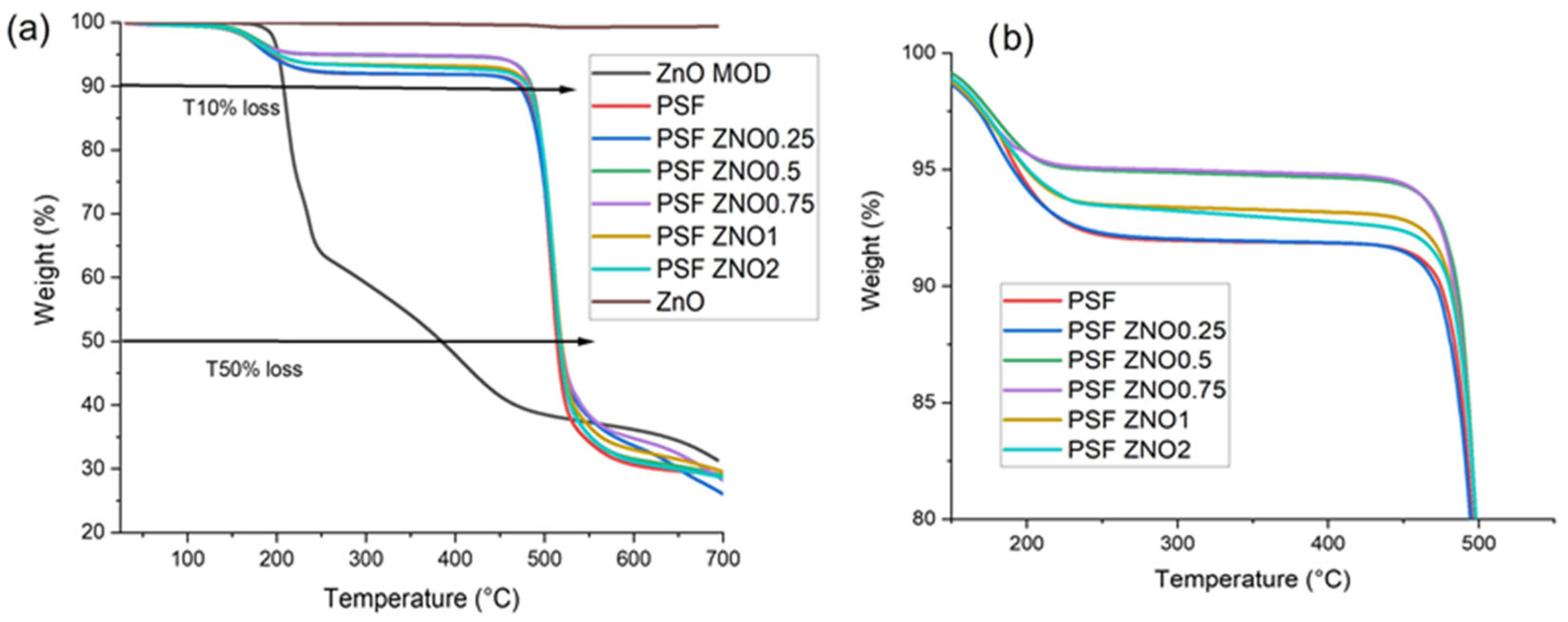

As shown in

Figure 3a,b, the thermogram presents the analysis of the ZnO and ZnO MOD nanoparticles samples, along with the TGA results for pure polysulfone and the nanocomposites obtained with polysulfone and modified. In pure ZnO, only a slight weight loss is observed, amounting to 0.6%, which is attributed to the evaporation of physically adsorbed water due to the nature of the porous structure of ZnO.

ZnOMOD (

Figure 3a), three weight losses were observed; the first between 188 and 240 °C, and the second between 252 and 459 °C. Finally, the third weight loss was from 488 to 634 °C. The first was due to the release of gases, and the second to the degradation of different L-serine compounds. Finally, the third loss is attributed to the degradation of the organic compound, L-serine.

It has been reported that, from 210 to 235 °C, there may be losses corresponding to the melting point of L-serine, and, at 120 to 315 °C, studies indicate that this may be attributed to the decomposition of a layer of L-serine on the surface by modifying ZnO particles [

28].

Modifications of ZnO nanoparticles with diacids similar to L-serine have been carried out, but using different process steps and reflux heating, these coatings show good thermal stability due to their decomposition at high temperatures (360–455 °C) [

29].

The TGA of pure polysulfone and PSFZNO films (

Figure 3b) at different concentrations indicate a first weight loss at approximately 152 to 200 °C, corresponding to the elimination of CH

3Cl. Thereafter the films remain thermally stable up to 463 °C, the second weight loss begins at 471 °C and ends at 526 °C, corresponding to structural modifications due to the crosslinking of the polymer during thermal degradation [

30]. Finally, a third weight loss event occurred as a result of the thermal decomposition of the polymer matrix, with a temperature range of 535 to 680 °C.

Degradation results have been reported at temperatures between 500 and 600 °C in polysulfone membranes and ZnO nanoparticles using a phase inversion method [

31].

Lisa et al. in 2003 [

29] stated that the thermal degradation of chloromethylated polysulfone derivatives occurs in three stages, with different weight losses depending on the nature of the substituents. Furthermore, it was noted that the most significant weight loss in these compounds occurs during the third stage of thermal degradation, which agrees with the results reported in the present study.

In

Table 3, the T-10% loss, T-50% loss, T max (°C) of the standard deviation, and residue at 800 °C can be observed. In this table, it can be observed that, at T-10% loss, the pure PSF and PSF ZNO 0.25 samples have temperatures of 477.63 and 474.12 °C, respectively, and, as the content of the reinforcing particles increases, the thermal stability increases, with the PSF ZNO 0.5 sample reaching the thermal stability threshold, presenting 487.32 °C, and then, as the content increases, the thermal stability decreases for the PSF ZNO 0.75, PSF ZNO 1, and PSF ZNO 2 samples, being between 482.60 and 485.11 °C.

For T-50% loss (°C), the sample with the lowest thermal stability was PSF, and the PSF ZNO films increased their stability, with temperatures ranging from 516 to 519 °C.

At T max (°C), the samples containing modified ZnO exhibited a higher temperature compared to the pure PSF, which had 508.40 °C.

Other research has reported that incorporating materials such as carbon black into a polysulfone matrix by mixing in solution at concentrations of 0.25, 0.5, and 1% wt improves thermal stability in the nanocomposites obtained due to homogeneously dispersed carbon black in the polymer matrix. As a result, it prevents thermal transfer and causes stability in the nanocomposite; this same phenomenon occurs in the present study [

17].

As is well known, the melting point of ZnO is quite high, reaching 1975 °C. The dispersion of these nanoparticles in the polysulfone matrix significantly enhances its thermal stability. The spherical particles limit heat transfer through the polymer nanocomposite, even with a low loading of 0.5%, with the PSF ZNO 0.5 sample being the most thermally stable.

Due to their nanometric size, the nanoparticles tend to agglomerate due to electrostatic forces. In the case of our materials, the PSF ZNO 0.5 sample demonstrates optimal dispersion in the medium and exhibits excellent thermal stability. This may be due to the fact that, with the 0.5% loading and the energy applied by the ultrasound, the dispersion was highly effective and homogenized throughout the polysulfone polymer matrix, thereby helping to create barriers to heat transfer. At higher loading percentages (PSF ZNO 1 and PSF ZNO 2), distribution did occur, but the particles were deposited at the edges of the agglomerated material. This resulted in unrestricted heat transfer and a larger free area where the polymer chains could break and the polymer nanocomposite could degrade more easily.

The percentage of residual mass at 800 degrees Celsius is shown in

Table 3. As illustrated, the percentage of residue obtained in all cases exceeds the theoretical percentage. This may be due to the polysulfone polymer’s tendency to leave residue and its degradation at high temperatures above 510 degrees Celsius, as indicated in the table.

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

The film structures were studied by XRD, wherein in

Figure 4, the diffractograms of the pristine polysulfone are observed, where only one amorphous peak centered at 18.37° is observed, which agrees with the literature [

17,

32]. Unmodified ZnO exhibits three peaks characteristic of the structure [

33]. On the other hand, the modified ZnO presents more peaks due to the presence of the functional groups of L-serine. It is also observed that the intensity of the characteristic peaks of ZnO decreases; this is due to the greater presence of l-serine on the surface of ZnO, which has already been reported for modifications using citric acid [

18]. In the ZnOMOD sample, the peaks corresponding to the structure wurtzite ZnO are displaced to 30°, 31.8°, and 32.5°. This may be due to the chemical modification with L-serine; in addition, the characteristic peak of L-serine is observed at 22.8°, and other signals in the XRD that range from 10° to 20° can probably be attributed to the peptide bonds formed between the amino acids.

PSFZNO films at concentrations of 0.25%, 0.5%, 0.75%, 1%, and 2% show diffraction patterns with a broad band typical of the amorphous polymer at 18.44°, 18.60°, 18.73°, and 19°, respectively. Only a shift in the main peak of polysulfone is observed, indicating that the incorporation of ZnO consists of a single polymer and nanoparticle phase [

34]. The concentration of nanoparticles is a critical factor in the modification of the polymer structures. It has been reported that at concentrations exceeding 3%, the characteristic peaks of ZnO become discernible [

22]. The crystal size (

L) of the samples was determined using the Scherrer Equation (7).

where

λ is the X-ray wavelength,

β is the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) intensity of the peak, and

θ is the Bragg’s angle. The intensity of the main peak of the polysulfone decreases as the percentage concentration of ZnO increases, as shown in

Table 4. The crystal size is determined using the Scherrer equation, which is based on the width of the main peak of the polysulfone.

The displacement of the amorphous peak of the PSF when the ZnOMOD content and the crystal size increase, and the incorporation of ZnO without new peaks, suggests that the dopant atoms are incorporated into the lattice superficially.

3.4. Morfology

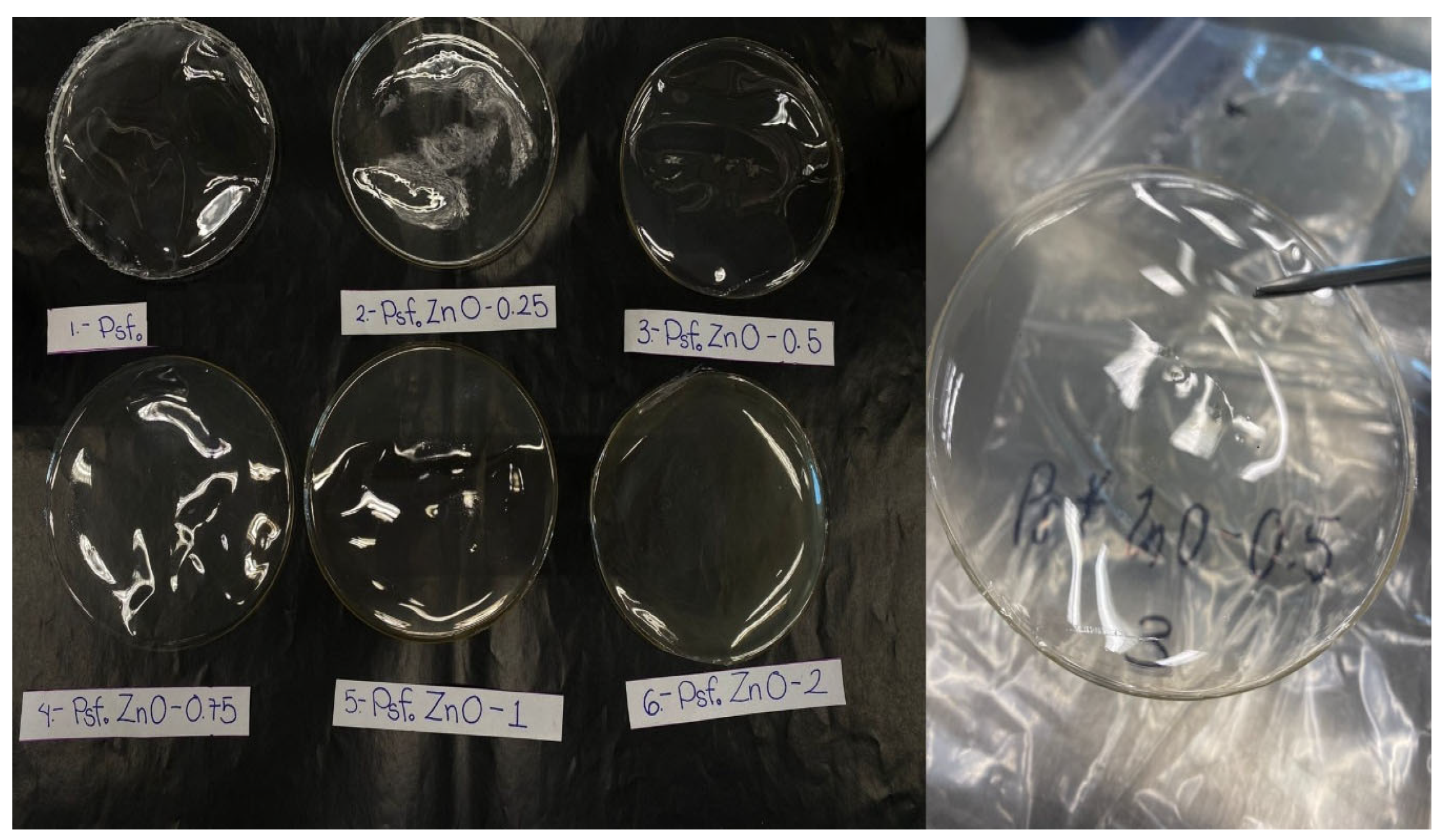

Figure 5 presents images of the films obtained by ultrasound-assisted solution mixing. A uniform film is observed with no visible agglomerates, flexible, and no pores are observed, so its surface is homogeneous and uniform. This is due to the use of ultrasound which disperses the ZnO nanoparticles. Furthermore, the chemical modification facilitates the interaction between the ceramic nanomaterial and the polymer. The thickness of the material is approximately 55 µm on average.

SEM analysis was used to observe the cross-sectional morphology of the polysulfone/ZnO film; the micrographs are shown in

Figure 6. In the case of the pure polysulfone film, a smooth and slightly rough morphology is observed; however, in the PSFZNO1 film, some roughness with few agglomerates is observed. The same is observed in the PSFZNO2 film; some roughness and small agglomerates are observed. Sarihan et al. prepared polysulfone/ZnO based membranes by the phase inversion technique due to the solvent and the concentration of the nanoparticles favors the creation of pores in the membrane. They observed that by increasing the concentration to 4% of ZnO, pores were no longer formed [

35].

Figure 7 shows the SEM/EDS micrographs of PSF and PSFZNO 2 at a higher magnification of 20,000×. This magnification was used to observe the ZnOMOD nanoparticles. Two small aggregates are observed due to the surface treatment of the ZnO with L-serine, which prevents the formation of larger agglomerates. The EDS of PSF (

Figure 7c) detects the characteristic elements of the polymer matrix: C, O, and S, without the presence of the filler.

Figure 7d presents the elemental analysis of the PSFZNO 2 film. The elements found are C, O, and S, corresponding to the polymer matrix. Zn and N correspond to the ZnO nanoparticles modified with L-serine. The amino functional group is found in the chemical structure of L-serine.

The uniform distribution of film components was confirmed by SEM/EDS elemental mapping. The elemental mapping obtained from pure polysulfone (

Figure 8) shows 59% carbon, 29% sulfur, 11% oxygen, and 0% zinc. The absence of zinc in the film is due to its pure polysulfone composition. When compared to the previously obtained EDS, the oxygen percentage remains consistent, while the carbon and sulfur percentages show variation due to the altered distribution resulting from the point EDS.

Figure 9 shows the SEM/EDS mapping of the PSFZNO2 film. The elements found in the film are Carbon 44%, Oxygen 8%, Sulfur 47%, and Zn 1%. Small clusters are observed, representing the red areas corresponding to the element Zn.

3.5. Evaluation of Polysulfone/ZnO Films in the Removal of Indigo and Crystal Violet Dyes

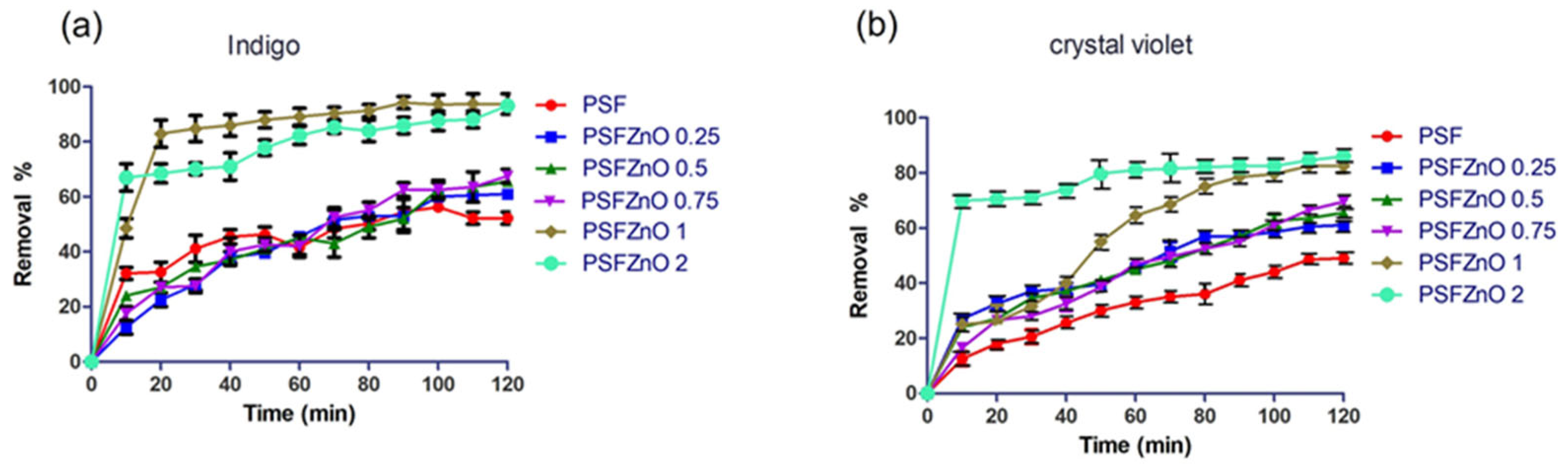

Contact time is a crucial parameter for an adsorption process, as it enables us to determine the maximum removal percentage and the time at which it occurs.

Figure 10a,b show the results of the removal of indigo and crystal violet. The neat polysulfone presents low removal percentages of 45% and 50% for indigo and crystal violet, respectively. When adding the modified ZnO nanoparticles to the polymer matrix, the removal percentage increases with both dyes. The PSFZNO 1 and PSFZNO 2 films exhibit 80% and 75% removal of crystal violet, respectively, and 80% and 90% removal of indigo, respectively. Indigo carmine adsorption studies have been reported using only ZnO nanoparticles, obtaining percentages of 70% removal [

36]. This is the first study to utilize a modified polysulfone/ZnO-based film, demonstrating its effectiveness in altering the contact time.

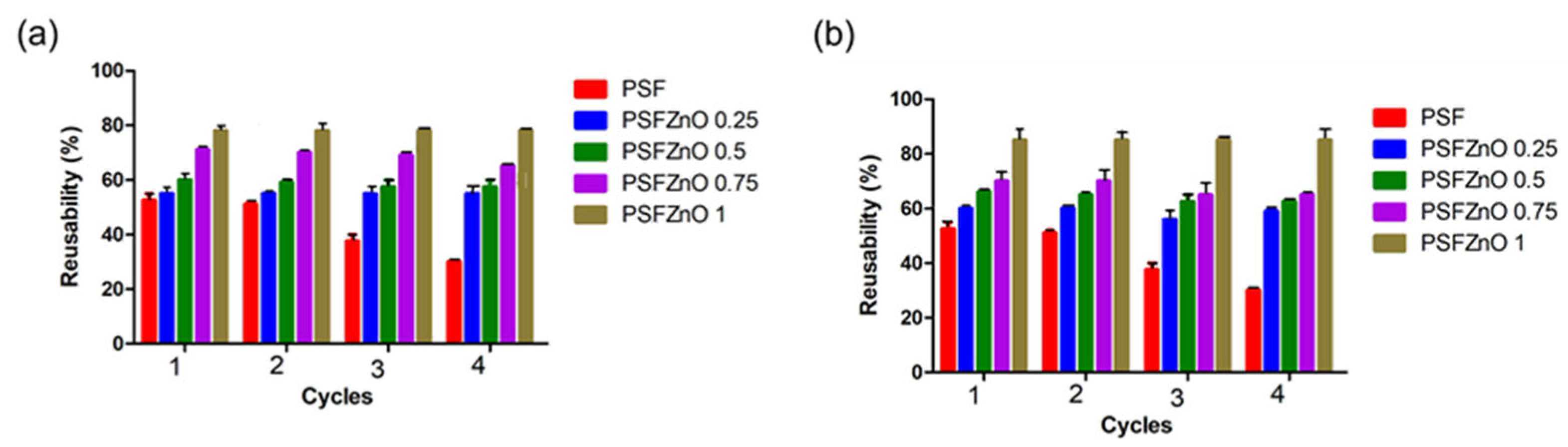

One way to contribute to the environment is to apply the reduction in the amount of waste, which can be accomplished by the three R’s: “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle.” The adsorbent can be reused after desorption. These films can be reused up to 4 consecutive cycles. Generally, a solvent is used against a saturated adsorbent, which causes it to release the adsorbed pollutant. In the case of the films, a wash with deionized water was used, followed by a mild acid, such as citric acid.

Figure 11a,b show the reusability percentages for indigo and crystal violet, respectively. In the case of polysulfone ordered from cycle 3, a decrease in the initial removal percentage is observed in both dyes, whereas in the PSFZNO films at different concentrations, this does not decrease; therefore, it is a material that can be reused.

Table 5 presents the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm results obtained from the experimental adsorption data of indigo and crystal violet dyes for all films produced. Comparing the data from both isotherms, the Langmuir model provides the best fit for both indigo and crystal violet dyes due to its higher R

2 value. The Langmuir isotherm describes a homogeneous, single-layer process, which agrees with the SEM results. These results show that the nanoparticles are deposited on the surface with few agglomerates, and the active adsorption sites are located in a single layer. Pai et al. report the adsorption of hydroxyapatite nanocomposites with different dyes, where the isotherm that best fits is Langmuir, which agrees with what was reported in this work for films composed of a polymer and inorganic nanoparticles [

37].

Table 6 summarizes the adsorption data results fitted to the pseudo-first and pseudo-second order models for indigo and crystal violet. As the concentration of nanoparticles in the film increases, the equilibrium adsorption capacity, qe, also increases with indicating that PSFZNO2 is the optimal film. This is due to its greater number of active adsorption sites for both dyes, which results in a higher adsorption rate. The results indicate that both indigo and crystal violet demonstrate a coefficient of variation that best aligns with the pseudo-second order model, suggesting a probable chemisorption process.

4. Conclusions

In this research, polysulfone-based films (PSF) with chemically modified ZnO nanoparticles containing L-serine were obtained using the sonochemical method for application as an adsorbent material for indigo and crystal violet dyes. The L-serine modification demonstrated a beneficial effect by interacting with the dyes, successfully removing these contaminants.

Infrared spectroscopy results indicate the formation of a film with interactions between the functional groups of the L-serine-modified ZnO and the sulfone group of the polymer matrix. X-ray diffraction revealed an amorphous peak of the polymer, which shifted upon incorporation of the ZnO nanoparticles. The thermal stability of the film increased with increasing ZnO concentration. The micrographs obtained show the formation of a homogeneous and uniform film with few aggregates, suggesting that ultrasound homogeneously disperses the nanoparticles within the polymer matrix. The application of these films resulted in 80% and 90% dye removal for crystal violet and indigo, respectively.

The experimental kinetic data demonstrated that the pseudo-second-order model best describes the adsorption process for the dyes, indicating that chemisorption occurs. Regarding the fitting of the equilibrium adsorption data, a better fit was found for both dyes; the Langmuir model describes the process, indicating the formation of a monolayer on the film surface.

The current outlook for the use of these materials is of great importance, since water scarcity is a high-impact issue worldwide. In addition, future research endeavors will involve testing these materials in real-world and contaminated environments to further explore their potential applications.

The sixth of the global objectives, clean water and sanitation, has garnered attention due to the global shortage of freshwater and the pollution of rivers, oceans, and seas. Efforts have been made to address this problem by improving water quality through pollution reduction and sanitation processes.