Sr2+ and Eu3+ Co-Doped Whitlockite Phosphates Ca8−xSrxZnEu(PO4)7: Bioactivity, Antibacterial Potential, and Luminescence Properties for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

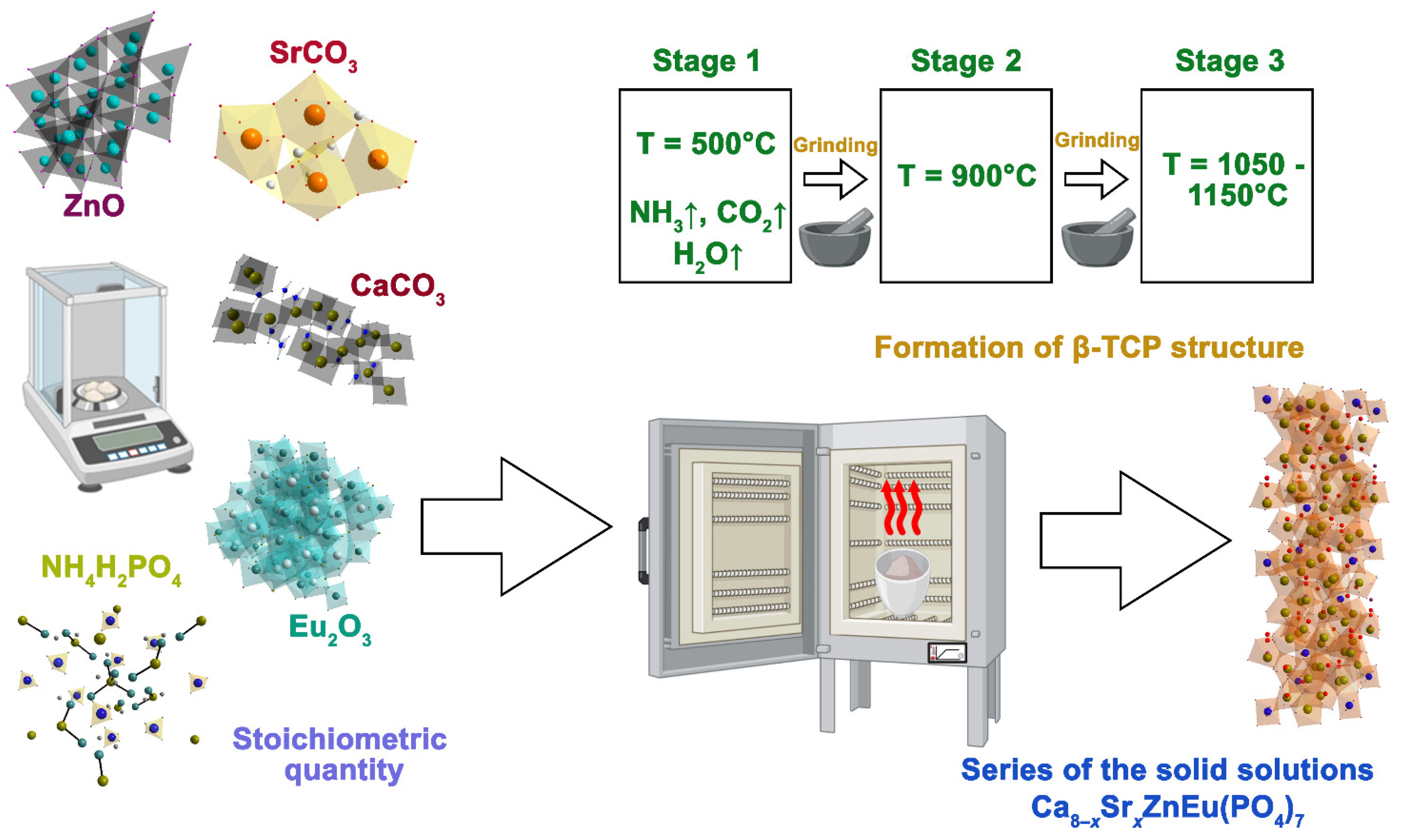

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Methods of Investigation

2.2.1. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) Study

2.2.2. SEM Study

2.2.3. FTIR-Spectroscopy

2.2.4. Photoluminescence Study

2.2.5. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Isolation

2.2.6. MTT Assay Study

2.2.7. Osteogenic Differentiation Study

2.2.8. Antimicrobial Activity

2.2.9. Statistical Analysis

2.2.10. Dissolution Behavior

3. Results and Discussion

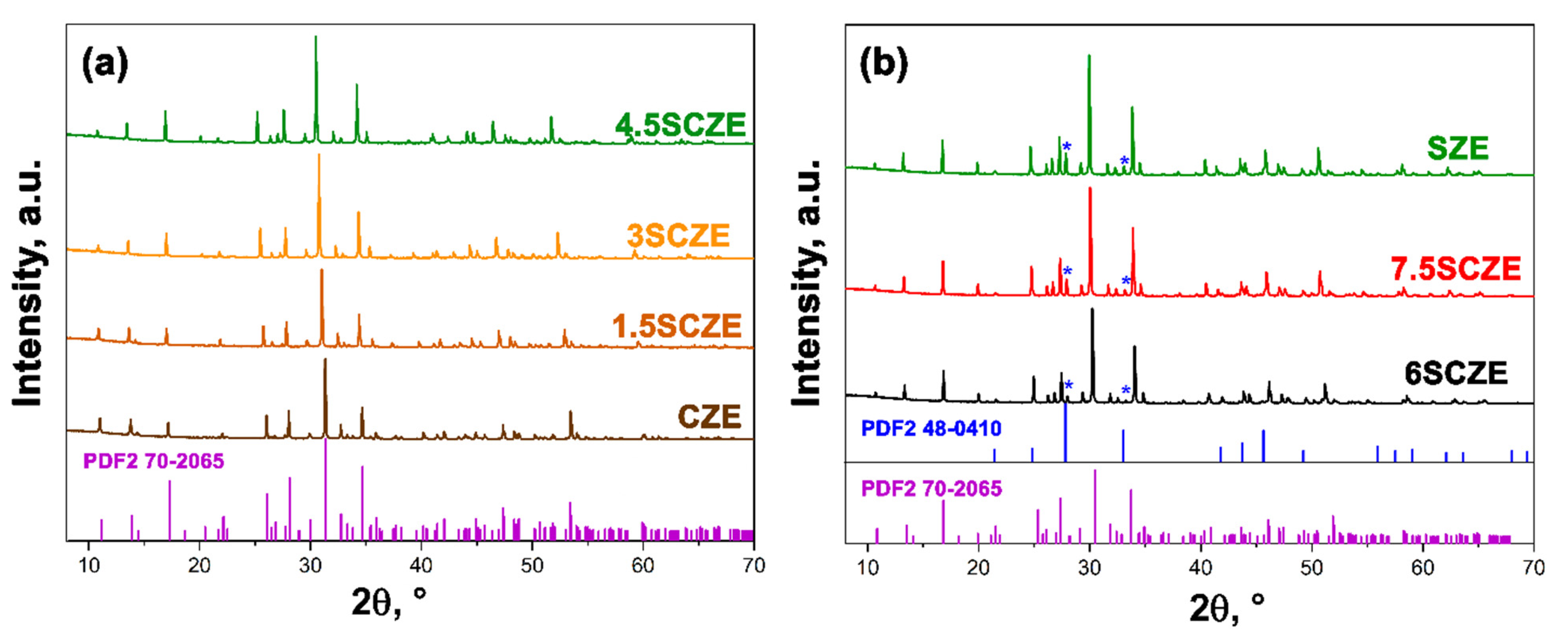

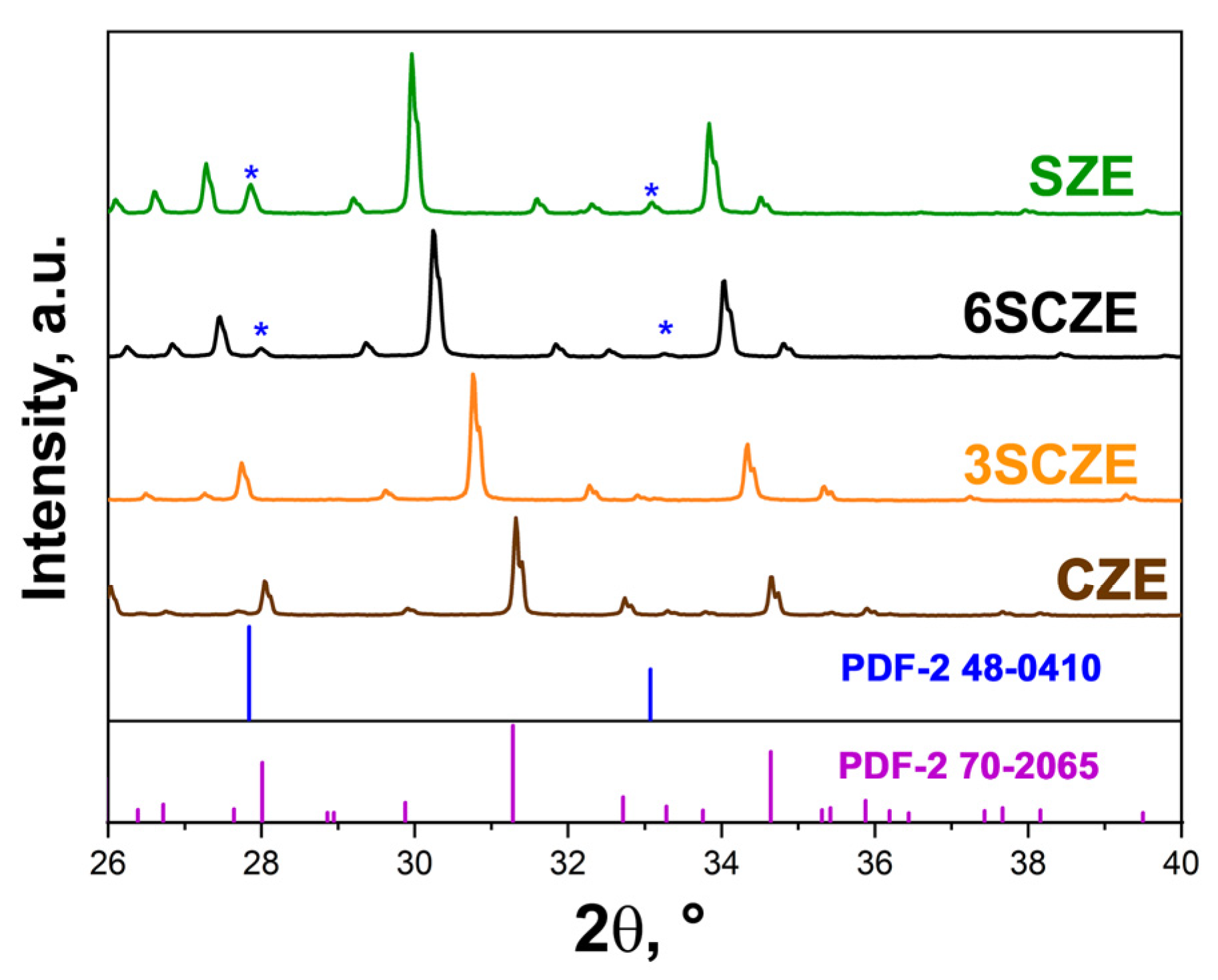

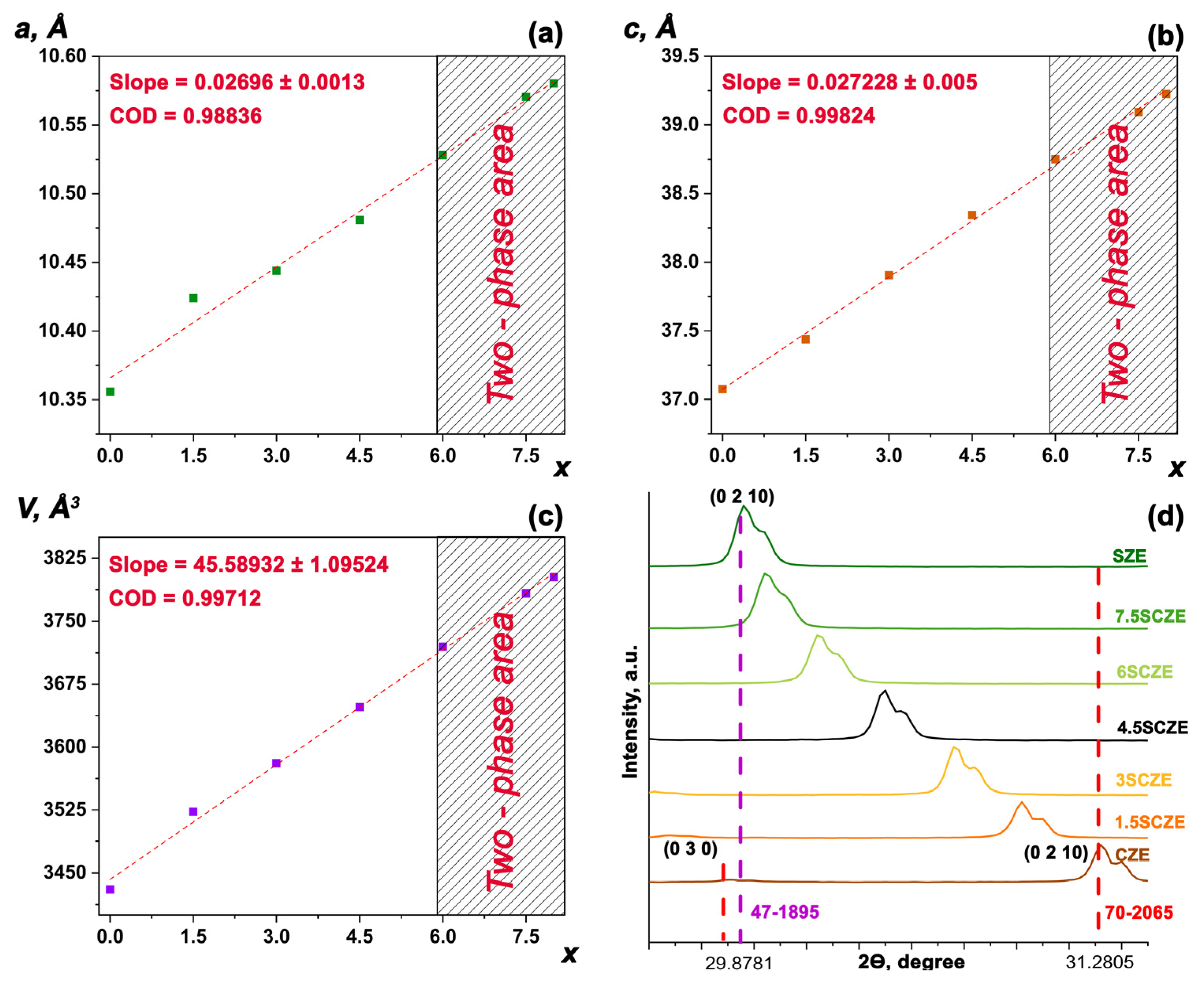

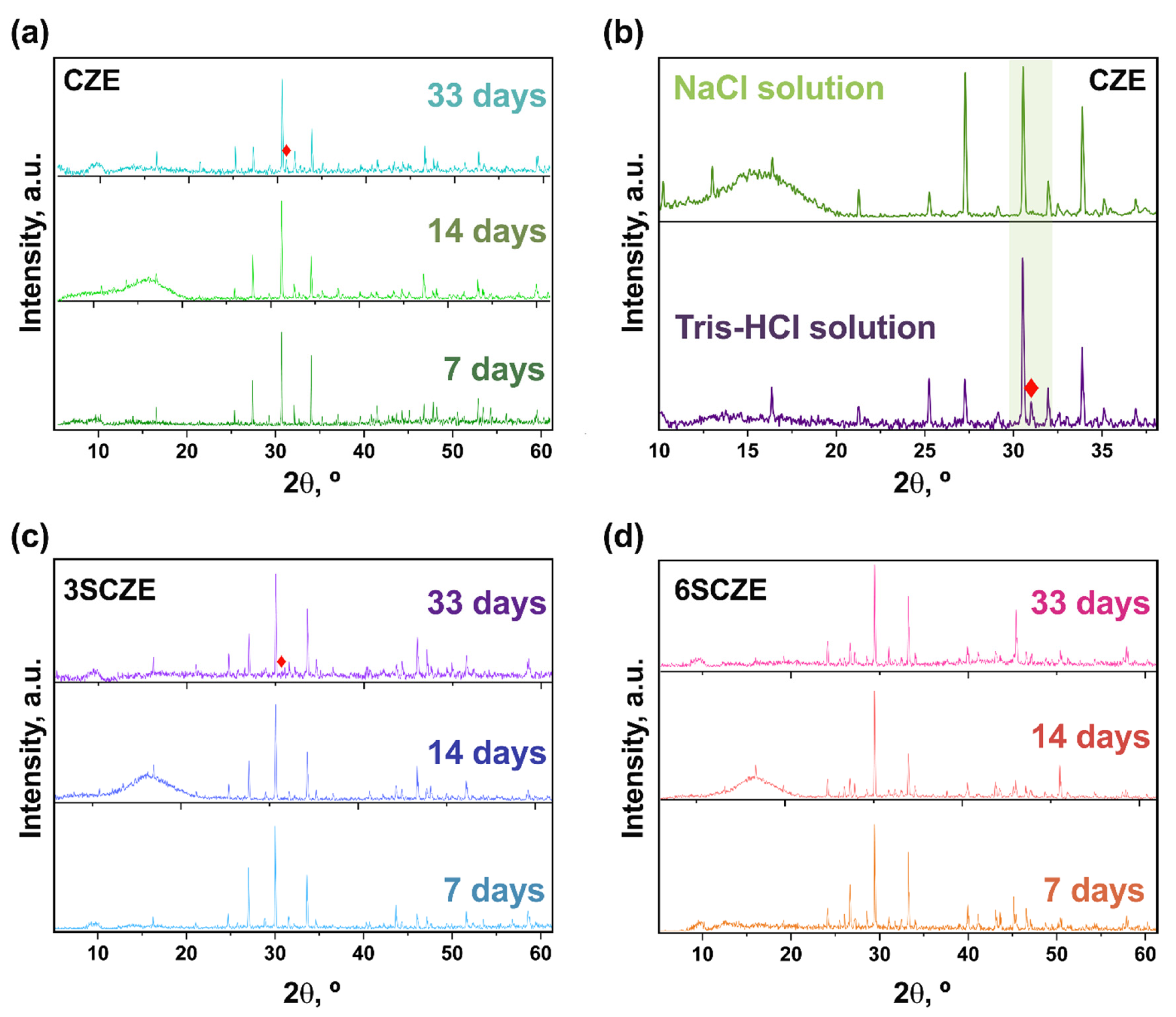

3.1. PXRD Study

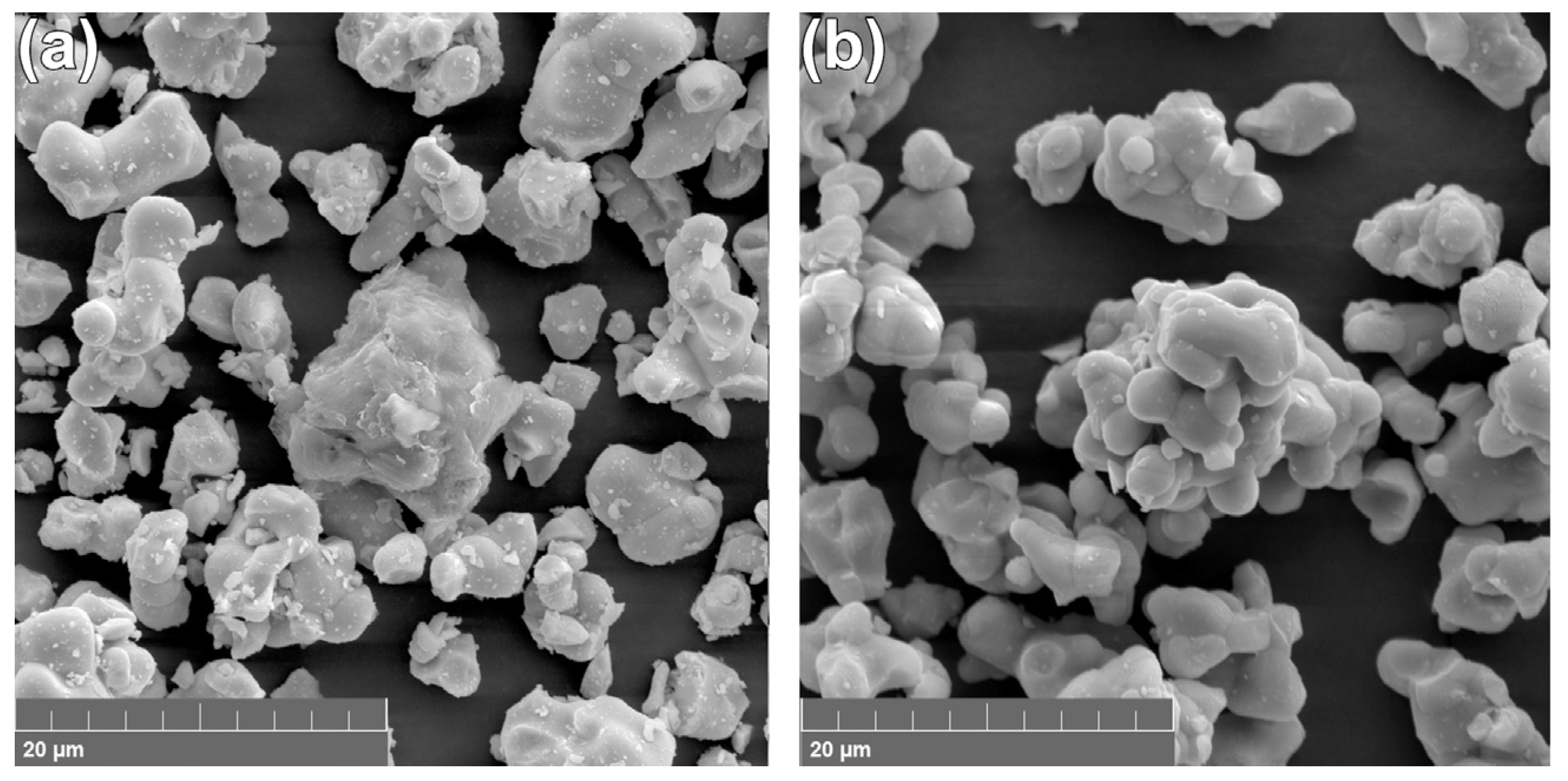

3.2. SEM Results

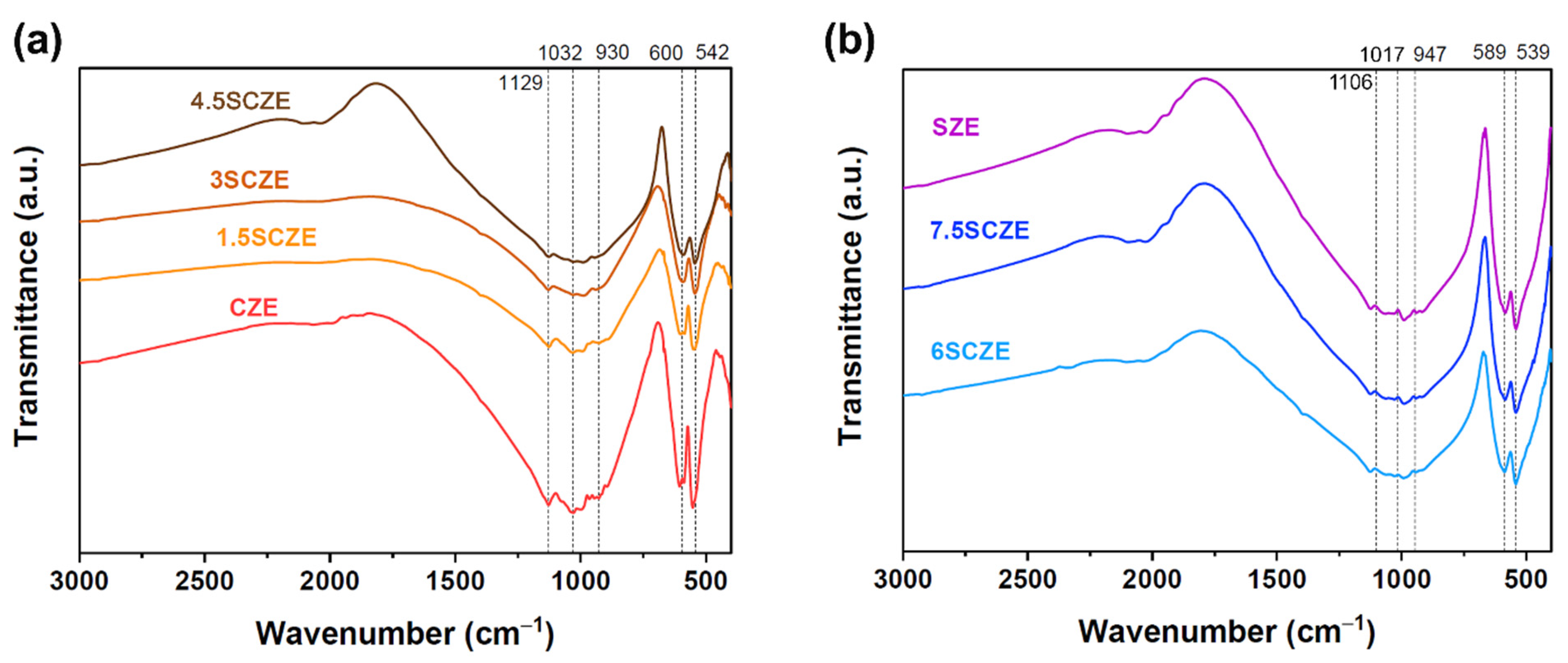

3.3. FTIR Spectroscopy

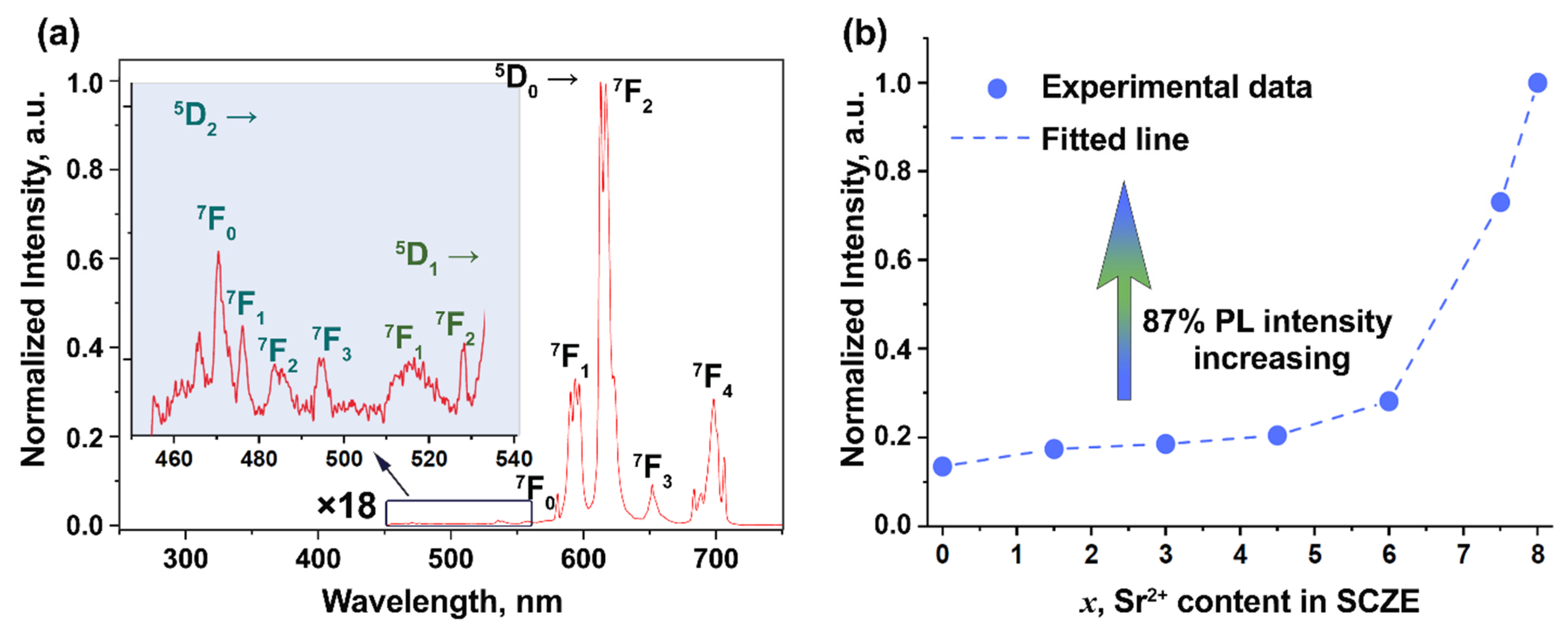

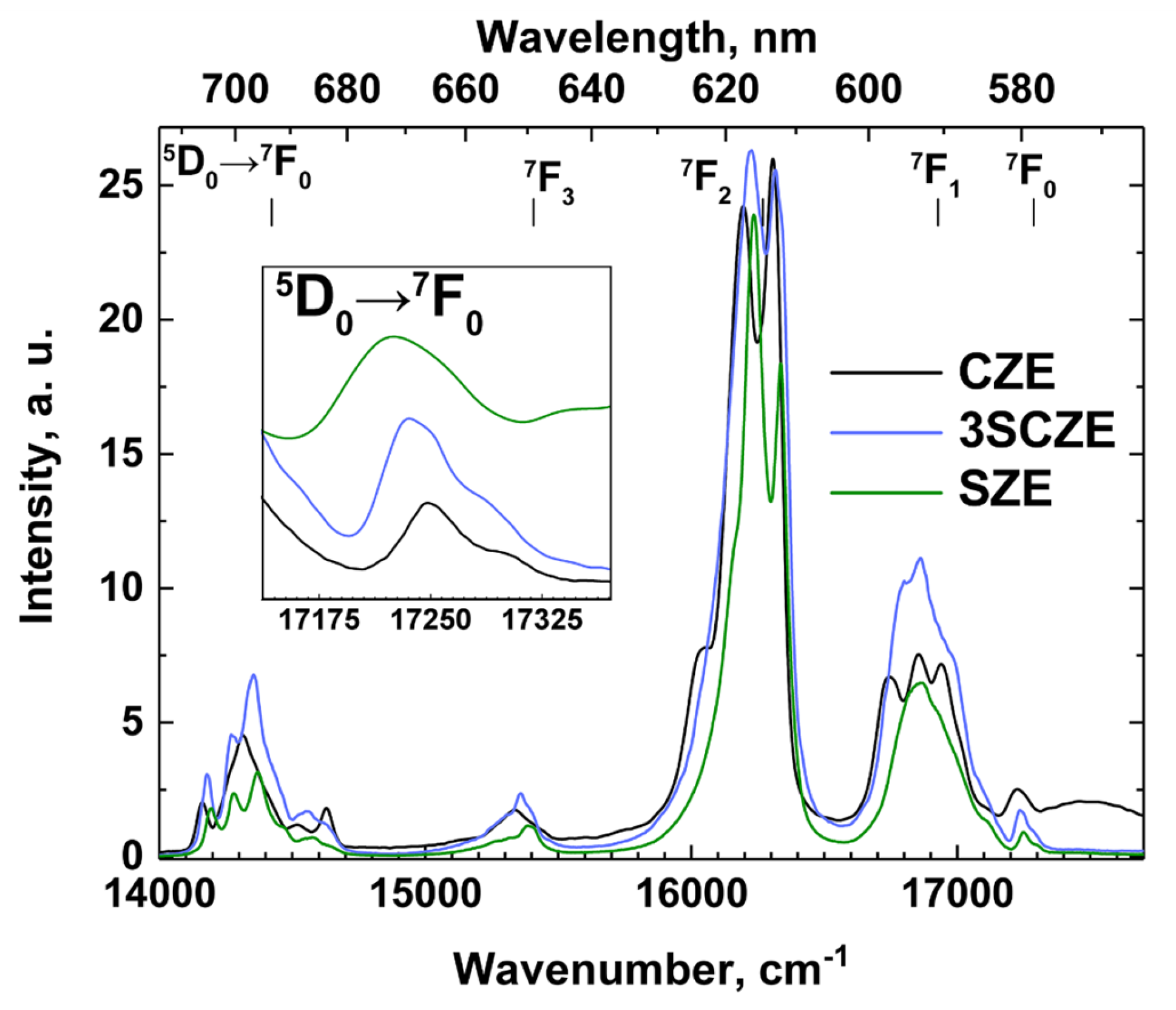

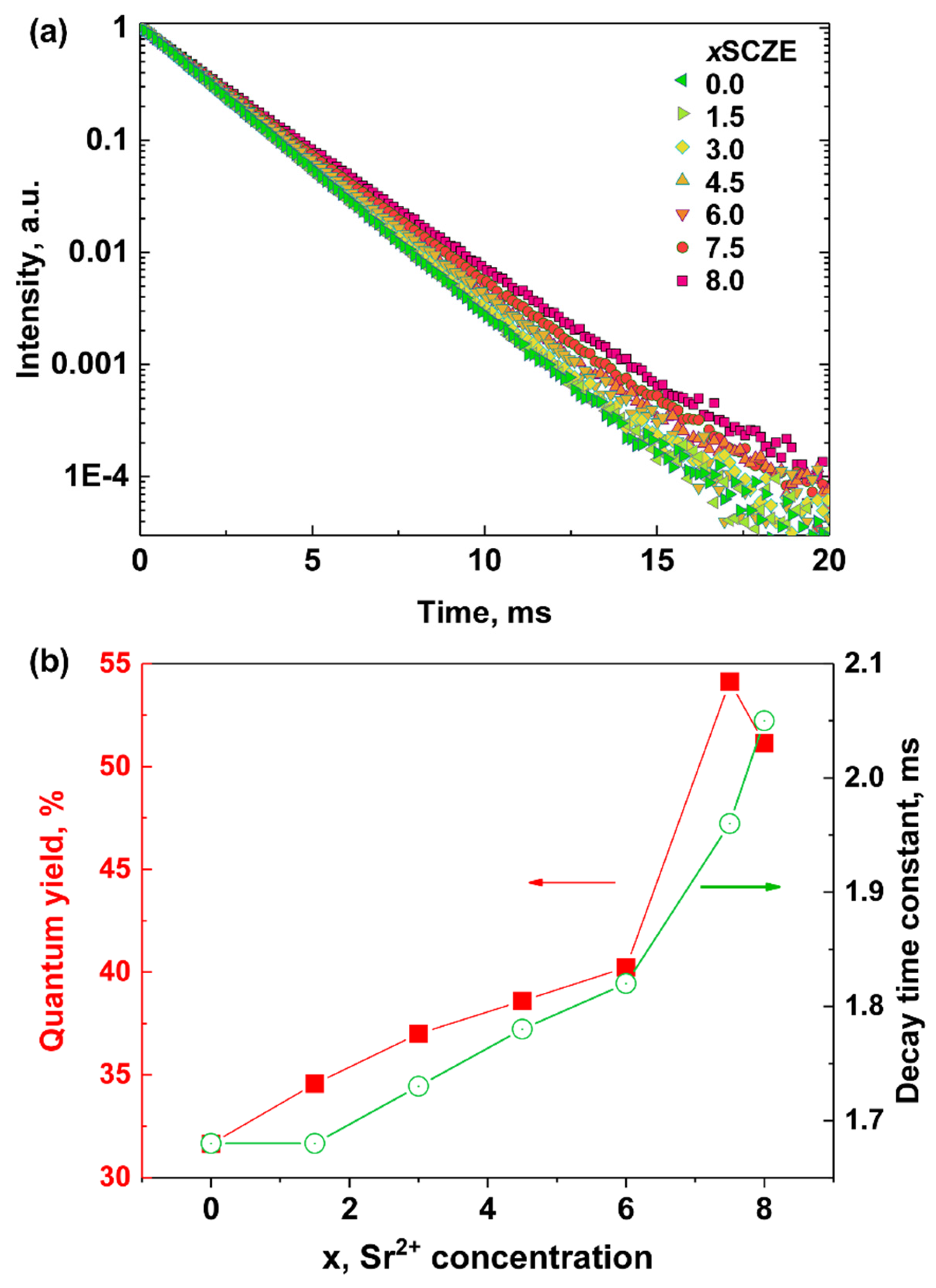

3.4. Photoluminescence Spectroscopy

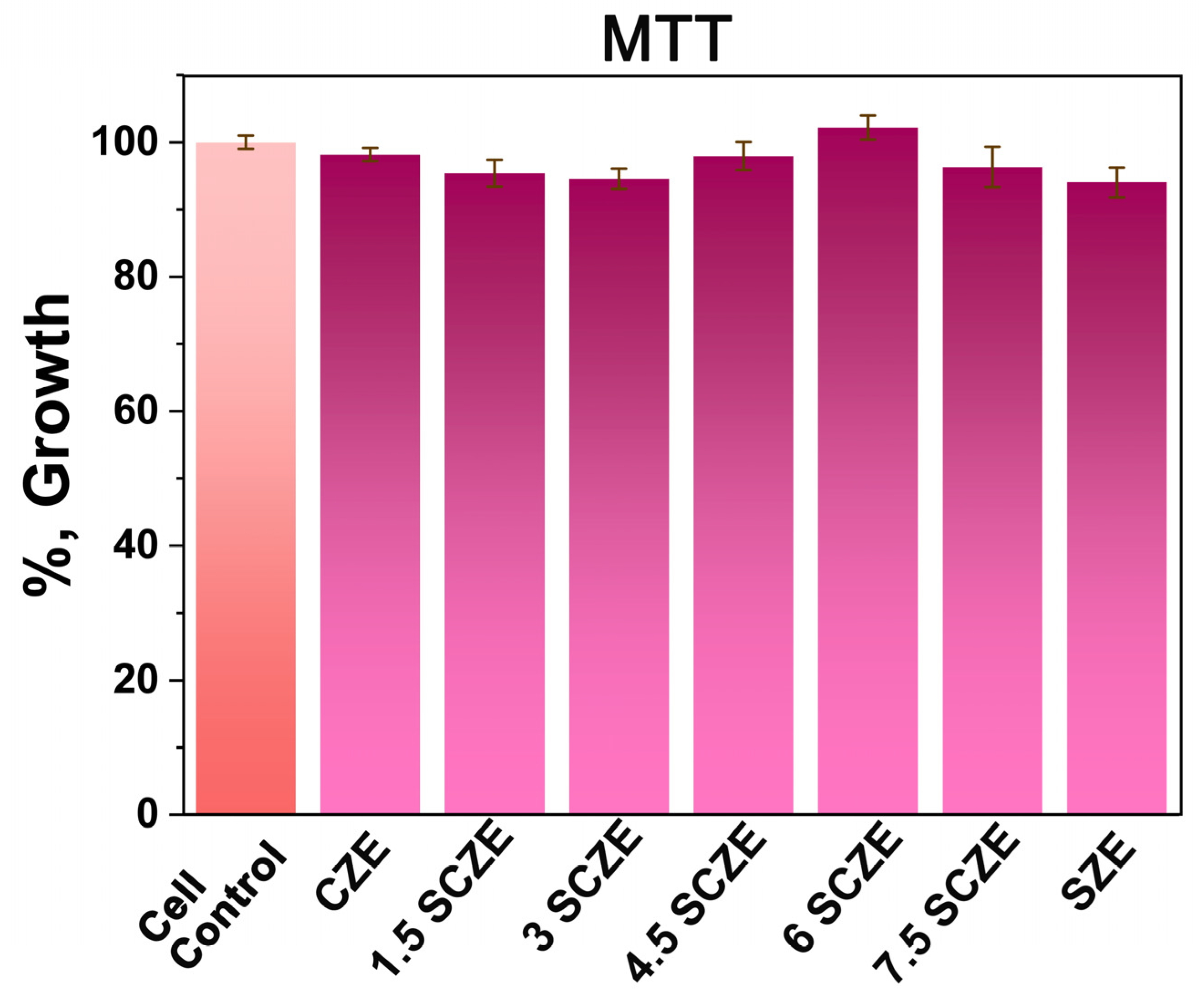

3.5. MTT Assay

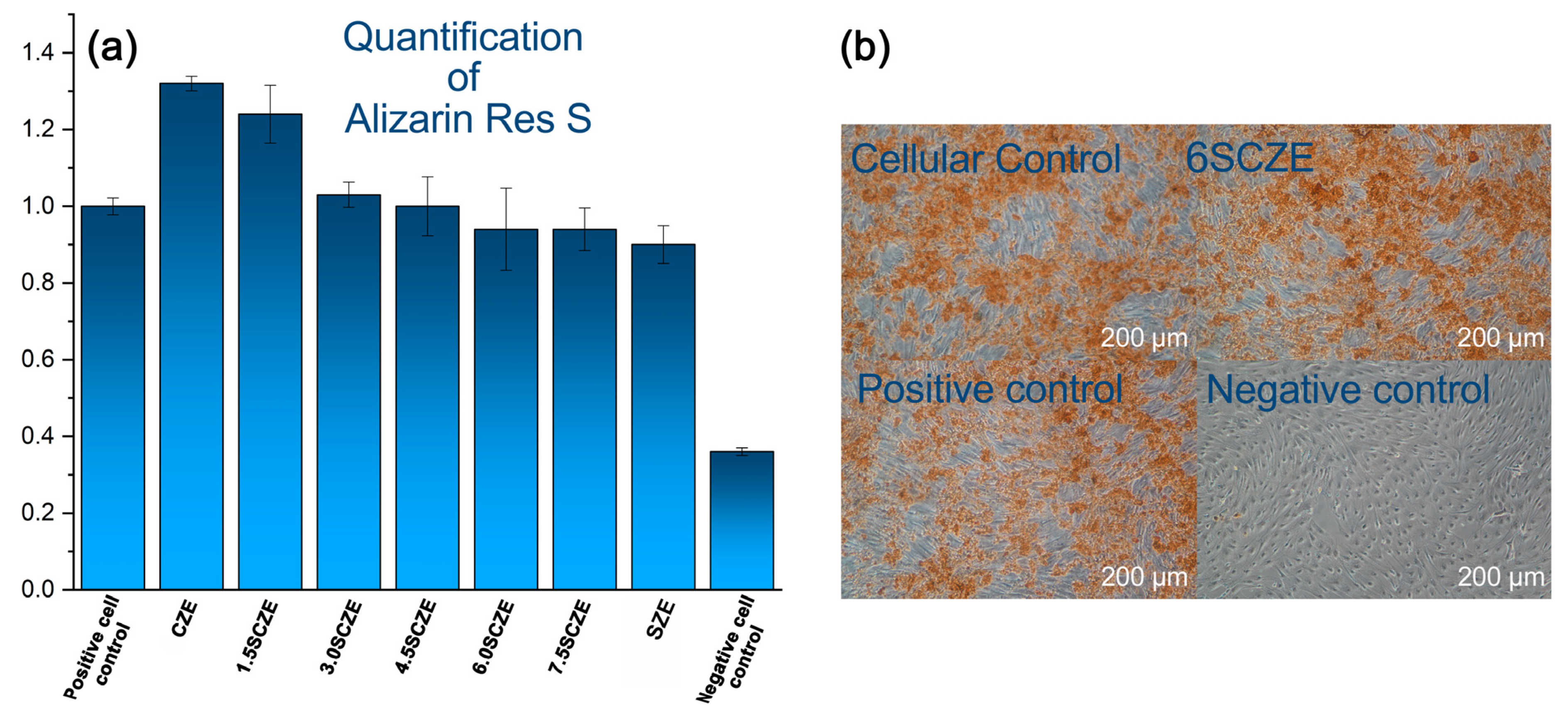

3.6. Osteogenic Differentiation

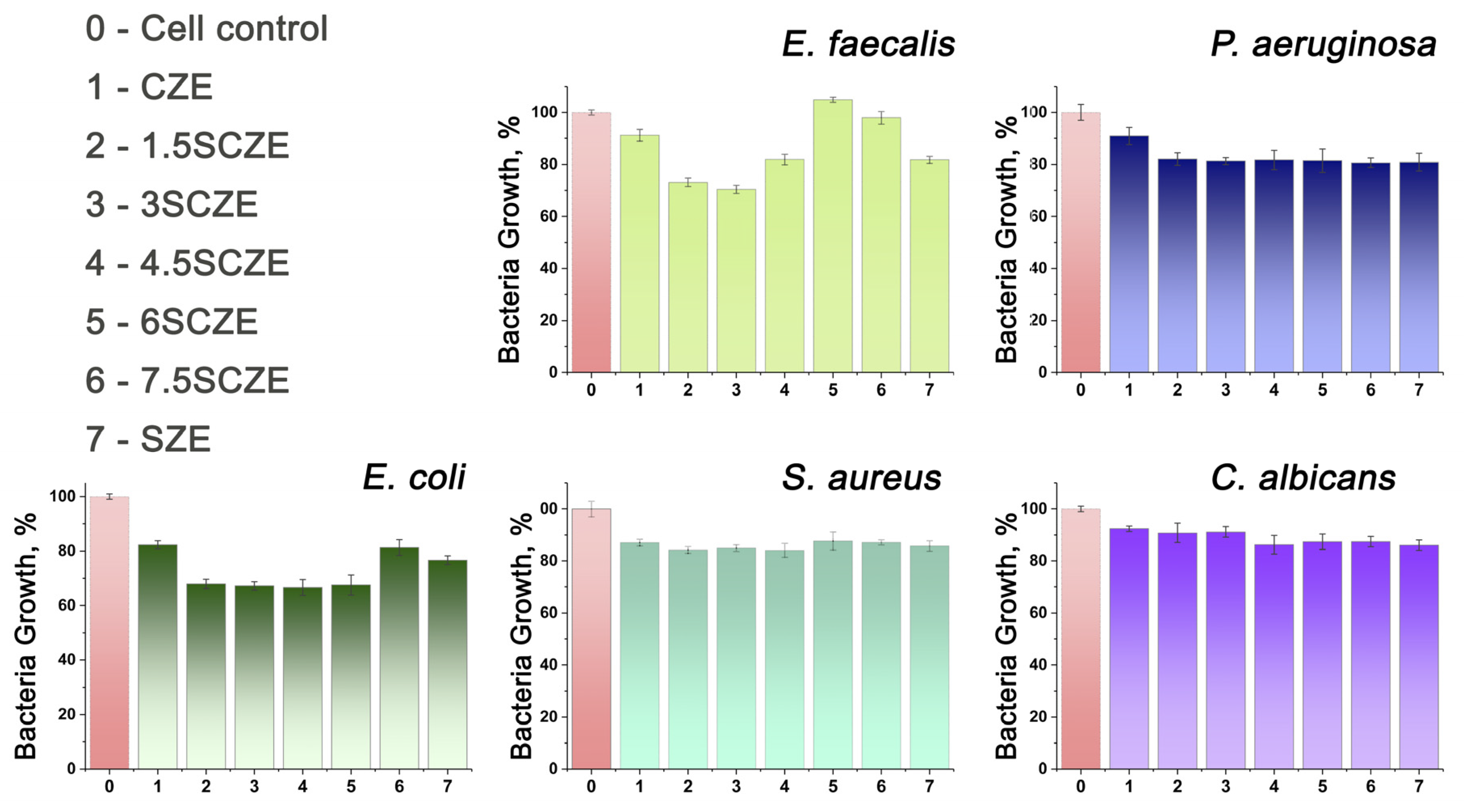

3.7. Antibacterial Activity

3.8. Dissolution Behavior

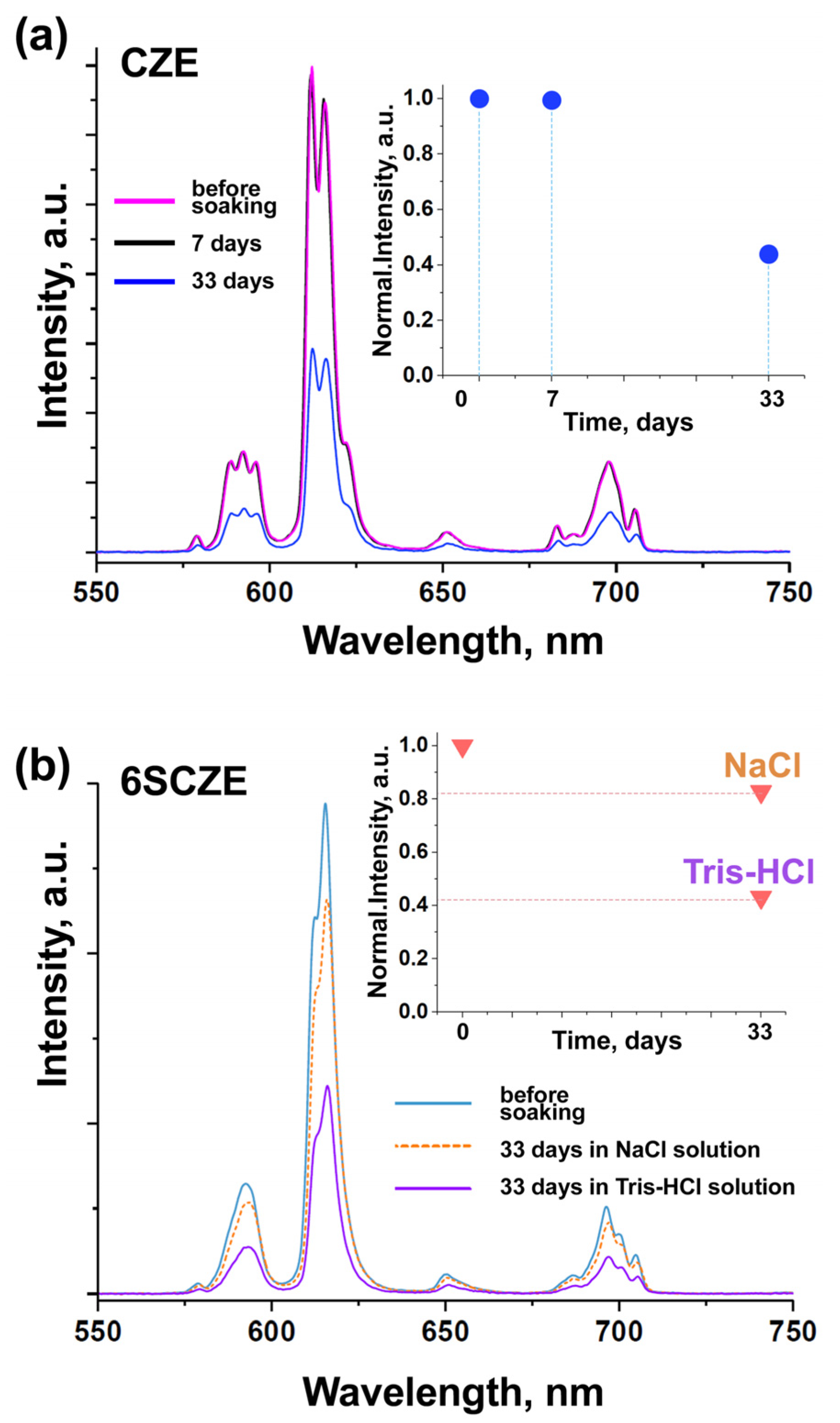

3.9. Photoluminescence Control of Dissolution

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Functionalized Calcium Orthophosphates (CaPO4) and Their Biomedical Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 7471–7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yeung, K.W.K. Bone Grafts and Biomaterials Substitutes for Bone Defect Repair: A Review. Bioact. Mater. 2017, 2, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komori, T. Regulation of Osteoblast Differentiation by Transcription Factors. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006, 99, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulina, N.V.; Khvostov, M.V.; Borodulina, I.A.; Makarova, S.V.; Zhukova, N.A.; Tolstikova, T.G. Substituted Hydroxyapatite and β-Tricalcium Phosphate as Osteogenesis Enhancers. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 33258–33269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardemil, C.; Elgali, I.; Xia, W.; Emanuelsson, L.; Norlindh, B.; Omar, O.; Thomsen, P. Strontium-Doped Calcium Phosphate and Hydroxyapatite Granules Promote Different Inflammatory and Bone Remodelling Responses in Normal and Ovariectomised Rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trzaskowska, M.; Vivcharenko, V.; Benko, A.; Franus, W.; Goryczka, T.; Barylski, A.; Palka, K.; Przekora, A. Biocompatible Nanocomposite Hydroxyapatite-Based Granules with Increased Specific Surface Area and Bioresorbability for Bone Regenerative Medicine Applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, M.; Gelinsky, M. Strontium Modified Calcium Phosphate Cements—Approaches towards Targeted Stimulation of Bone Turnover. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 4626–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevet, R.; Fauré, J.; Benhayoune, H. Bioactive Calcium Phosphate Coatings for Bone Implant Applications: A Review. Coatings 2023, 13, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Jung, O.; Batinic, M.; Burckhardt, K.; Görke, O.; Alkildani, S.; Köwitsch, A.; Najman, S.; Stojanovic, S.; Liu, L.; et al. Biphasic Bone Substitutes Coated with PLGA Incorporating Therapeutic Ions Sr2+ and Mg2+: Cytotoxicity Cascade and In Vivo Response of Immune and Bone Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1408702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.-H.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, H.S.; Shin, H.; Shin, H. Biomineralization of Bone Tissue: Calcium Phosphate-Based Inorganics in Collagen Fibrillar Organic Matrices. Biomater. Res. 2022, 26, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönegg, D.; Essig, H.; Al-Haj Husain, A.; Weber, F.E.; Valdec, S. Patient-Specific Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate Scaffold for Customized Alveolar Ridge Augmentation: A Case Report. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2024, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atencio, D.; Azzi, A.D.A. Cerite: A new supergroup of minerals and cerite-(La) renamed ferricerite-(La). Mineral. Mag. 2020, 6, 928–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sblendorio, G.A.; Le Gars Santoni, B.; Alexander, D.T.L.; Bowen, P.; Bohner, M.; Döbelin, N. Towards an Improved Understanding of the β-TCP Crystal Structure by Means of “Checkerboard” Atomistic Simulations. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 43, 4130–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, M.; Sakai, A.; Kamiyama, T.; Hoshikawa, A. Crystal Structure Analysis of β-Tricalcium Phosphate Ca3(PO4)2 by Neutron Powder Diffraction. J. Solid State Chem. 2003, 175, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belik, A.A.; Morozov, V.A.; Deyneko, D.V.; Savon, A.E.; Baryshnikova, O.V.; Zhukovskaya, E.S.; Dorbakov, N.G.; Katsuya, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Stefanovich, S.Y.; et al. Antiferroelectric Properties and Site Occupations of R3+ Cations in Ca8MgR(PO4)7 Luminescent Host Materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 699, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikhtyar, Y.Y.; Spassky, D.A.; Morozov, V.A.; Deyneko, D.V.; Belik, A.A.; Baryshnikova, O.V.; Nikiforov, I.V.; Lazoryak, B.I. Site Occupancy, Luminescence and Dielectric Properties of β-Ca3(PO4)2-Type Ca8ZnLn(PO4)7 Host Materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 908, 164521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, G.; Watanabe, Y.; Yasui, Y.; Matsui, K.; Kawano, H.; Miyamoto, W. Induced Membrane Technique Using an Equal Portion of Autologous Cancellous Bone and β-Tricalcium Phosphate Provided a Successful Outcome for Osteomyelitis in Large Part of the Femoral Diaphysis—Case Report. Trauma Case Rep. 2021, 36, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyneko, D.V.; Zheng, Y.; Barbaro, K.; Lebedev, V.N.; Aksenov, S.M.; Borovikova, E.Y.; Gafurov, M.R.; Fadeeva, I.V.; Lazoryak, B.I.; Di Giacomo, G.; et al. Dependence of Antimicrobial Properties on Site-Selective Arrangement and Concentration of Bioactive Cu2+ Ions in Tricalcium Phosphate. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 21308–21323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangaraj, S.; Priyadarshini, I.; Swain, S.; Rautray, T.R. ZnO-Doped β-TCP Ceramic-Based Scaffold Promotes Osteogenic and Antibacterial Activity. Bioinspired Biomim. Nanobiomater. 2024, 13, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Y.B.A.; de Moura Júnior, D.; Farias, J.R.d.S.; Sales, V.R.A.; Costa, S.L.O.; Carvalho, G.K.G.; Sobrinho, N.d.O.; dos Santos, V.B.; Simões, V.d.N.; Braga, A.d.N.S. The Effect of the Incorporation of Mg in Beta Tricalcium Phosphate: A Brief Review. In Developments in Its Application in Science and Knowledge; Seven Editora: Ponta Grossa, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begam, H.; Dasgupta, S.; Bodhak, S.; Barui, A. Cobalt Doped Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Ceramics for Bone Regeneration Applications: Assessment of In Vitro Antibacterial Activity, Biocompatibility, Osteogenic and Angiogenic Properties. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 13276–13285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyneko, D.V.; Lebedev, V.N.; Barbaro, K.; Titkov, V.V.; Lazoryak, B.I.; Fadeeva, I.V.; Gosteva, A.N.; Udyanskaya, I.L.; Aksenov, S.M.; Rau, J.V. Antimicrobial and Cell-Friendly Properties of Cobalt and Nickel-Doped Tricalcium Phosphate Ceramics. Biomimetics 2023, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakrat, M.; Jodati, H.; Mejdoubi, E.M.; Evis, Z. Synthesis and Characterization of Pure and Mg, Cu, Ag, and Sr Doped Calcium-Deficient Hydroxyapatite from Brushite as Precursor Using the Dissolution-Precipitation Method. Powder Technol. 2023, 413, 118026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, I.D.; Oleynikova, E.I.; Pudovkin, M.S.; Nizamutdinov, A.S.; Semashko, V.V.; Gafurov, M.R.; Pavlov, I.S.; Zobkova, Y.O.; Petrakova, N.V.; Sirotinkin, V.P.; et al. Spectral and Kinetic Characteristics of Precipitated and Heat-Treated Hydroxyapatite and Tricalcium Phosphate Doped with Europium. Opt. Mater. 2025, 159, 116609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphof, R.; Lima, R.N.O.; Schoones, J.W.; Arts, J.J.; Nelissen, R.G.H.H.; Cama, G.; Pijls, B.G.C.W. Antimicrobial Activity of Ion-Substituted Calcium Phosphates: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.-Y.; Xing, Q.-G.; Fan, Y.-R.; Song, Q.-F.; Song, C.-H.; Han, Y. Polyacrylic acid complexes to mineralize ultrasmall europium-doped calcium phosphate nanodots for fluorescent bioimaging. Mater. Des. 2022, 221, 111008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, C.; Dubec, M.; Donne, K.; Bashford, T. Effect of Wavelength and Beam Width on Penetration in Light-Tissue Interaction Using Computational Methods. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.N.; Ponnilavan, V.; Lee, W.; Yoon, J. Zinc additions in calcium phosphate system. Phase behavior, microstructural and mechanical compatibility during sequential heat treatments. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 929, 167173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinusaite, L.; Kareiva, A.; Zarkov, A. Thermally Induced Crystallization and Phase Evolution of Amorphous Calcium Phosphate Substituted with Divalent Cations Having Different Sizes. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 2, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, G.A.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Bose, S. Effects of silica and zinc oxide doping on mechanical and biological properties of 3D printed tricalcium phosphate tissue engineering scaffolds. Dent. Mater. 2012, 2, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Zhang, K.-H.; Wu, J.; Wang, K.-W.; Tang, Q.-L.; Mo, X.-M. Europium-doped amorphous calcium phosphate porous nanospheres: Preparation and application as luminescent drug carriers. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011, 1, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungureanu, E.; Vladescu, A.; Parau, A.C.; Mitran, V.; Cimpean, A.; Tarcolea, M.; Vranceanu, D.M.; Cotrut, C.M. In Vitro Evaluation of Ag- and Sr-Doped Hydroxyapatite Coatings for Medical Applications. Materials 2023, 15, 5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentleman, E.; Fredholm, Y.C.; Jell, G.; Lotfibakhshaiesh, N.; O’Donnell, M.D.; Hill, R.G.; Stevens, M.M. The effects of strontium-substituted bioactive glasses on osteoblasts and osteoclasts in vitro. Biomaterials 2010, 14, 3949–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiforov, I.V.; Zhukovskaya, E.S.; Aksenov, S.M.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Pankrushina, E.A.; Deyneko, D.V. Structural Refinement and Optical Properties of Strontiowhitlockite-Based Mixed Phosphate-Vanadates. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 13669–13683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, M.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J. The Effect of Liraglutide on the Proliferation, Migration, and Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Periodontal Ligament Cells. J. Periodontal Res. 2019, 54, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, W.H.; Bragg, W.L. The Reflection of X-Rays by Crystals. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1913, 88, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqap, A.S.F.; Sopyan, I. Low Temperature Hydrothermal Synthesis of Calcium Phosphate Ceramics: Effect of Excess Ca Precursor on Phase Behavior. Indian J. Chem. Sect. A 2009, 48, 1492–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Jillavenkatesa, A.; Condrate, R.A. The Infrared and Raman Spectra of β-and α-Tricalcium Phosphate (Ca3(PO4)2). Spectrosc. Lett. 1998, 31, 1619–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnemans, K. Interpretation of Europium(III) Spectra. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 295, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyneko, D.V.; Lebedev, V.N.; Aksenov, S.M.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Pankratov, V.; Lazoryak, B.I.; Gosteva, A.N.; Barbaro, K.; Rau, J.V. Zn2+, Sr2+, and Sm3+ Tri-Doped Whitlockites: Luminescent Materials with Improved Bioactive and Antibacterial Properties. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 21117–21134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazoryak, B.I.; Stefanovich, S.Y.; Titkov, V.V.; Mosunov, A.V.; Nikiforov, I.V.; Kharovskaya, M.I.; Pankrushina, E.A.; Kubrin, S.P.; Deyneko, D.V. Polymorphism of Whitlockite-Type Phosphors Ca9–1.5xZnMeEux(PO4)7 and Enhancement of Eu3+ Luminescence with Me = Li, Na. Mater. Res. Bull. 2025, 188, 113396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Sun, L.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, M.; Peng, Z.; Yang, J.; Zheng, L. Toxicity of rare earth elements europium and samarium on zebrafish development and locomotor performance. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 137213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, H.; Gregory, T.M.; Brown, W.E. Solubility of Ca5(PO4)3OH in the System Ca(OH)2-H3PO4-H2O at 5, 15, 25, and 37 °C. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. Sect. A Phys. Chem. 1977, 81, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.; Torii, R.; Burriesci, G.; Bertazzo, S. Whitlockite Can Be a Substrate for Apatite Growth in Simulated Body Fluid. Materialia 2025, 40, 102409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, M.C.F.; Costa, M.O.G. On the Solubility of Whitlockite, Ca9Mg(HPO4)(PO4)6, in Aqueous Solution at 298.15 K. Monatshefte Chem. 2018, 149, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, L.E.; Pierce, J.A.; Kajdi, C.N. The Solubility of the Phosphates of Strontium, Barium, and Magnesium and Their Relation to the Problem of Calcification. J. Colloid Sci. 1954, 9, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoffersen, J.; Christoffersen, M.R.; Kolthoff, N.; Bärenholdt, O. Effects of Strontium Ions on Growth and Dissolution of Hydroxyapatite and on Bone Mineral Detection. Bone 1997, 20, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.B.; Li, Z.Y.; Lam, W.M.; Wong, J.C.; Darvell, B.W.; Luk, K.D.K.; Lu, W.W. Solubility of Strontium-Substituted Apatite by Solid Titration. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gbureck, U.; Barralet, J.E.; Spatz, K.; Grover, L.M.; Thull, R. Ionic Modification of Calcium Phosphate Cement Viscosity. Part I: Hypodermic Injection and Strength Improvement of Apatite Cement. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 2187–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oesterle, A.; Boehm, A.V.; Müller, F.A. Photoluminescent Eu3+-Doped Calcium Phosphate Bone Cement and Its Mechanical Properties. Materials 2018, 11, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.R.O.; Lima, N.B.; Guilhen, S.N.; Courrol, L.C.; Bressiani, A.H.A. Evaluation of Europium-Doped HA/β-TCP Ratio Fluorescence in Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Nanocomposites Controlled by the pH Value during the Synthesis. J. Lumin. 2016, 180, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Assignment in PO43− | IR Peaks, cm−1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x in Ca8−xSrxZnEu(PO4)7 | |||||||

| 0 | 1.5 | 3 | 4.5 | 6 | 7.5 | 8 | |

| ν3 [P–O] | 1128 s | 1125 s | 1128 s | 1127 s | 1123 s | 1123 s | 1123 s |

| ν3 [P–O] | 1074 s | 1058 s | 1054 s | 1069 s | 1069 s | ||

| ν3 [P–O] | 1031 s | 1031 s | 1031 s | 1031 s | 1027 s | 1050–1032 s | 1046 s |

| ν3 [P–O] | 995 s | 992 s | 992 s | 993 s | 992 s | 992 s | 992 s |

| νs1 [P–O] | 964 s | 964 s | |||||

| νs1 [P–O] | 945 s | 930 | 945 | 945 s | 939 s | 942 s | 942 s |

| ν4 [O–P–O] | 605 s | 602 s | 594 s | 591 s | 587 s | 587 s | 585 s |

| ν4 [O–P–O] | 584 s | 584 s | 547 s | 545 s | 544 s | 543 s | 543 s |

| ν2 [O–P–O] | 444 w | 438 w | 428 w | 463 w | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deyneko, D.V.; Lebedev, V.N.; Nikiforov, I.V.; Titkov, V.V.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Barbaro, K.; Caciolo, D.; Aksenov, S.M.; Fosca, M.; Lazoryak, B.I.; et al. Sr2+ and Eu3+ Co-Doped Whitlockite Phosphates Ca8−xSrxZnEu(PO4)7: Bioactivity, Antibacterial Potential, and Luminescence Properties for Biomedical Applications. Coatings 2025, 15, 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121453

Deyneko DV, Lebedev VN, Nikiforov IV, Titkov VV, Shendrik RY, Barbaro K, Caciolo D, Aksenov SM, Fosca M, Lazoryak BI, et al. Sr2+ and Eu3+ Co-Doped Whitlockite Phosphates Ca8−xSrxZnEu(PO4)7: Bioactivity, Antibacterial Potential, and Luminescence Properties for Biomedical Applications. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121453

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeyneko, Dina V., Vladimir N. Lebedev, Ivan V. Nikiforov, Vladimir V. Titkov, Roman Yu. Shendrik, Katia Barbaro, Daniela Caciolo, Sergey M. Aksenov, Marco Fosca, Bogdan I. Lazoryak, and et al. 2025. "Sr2+ and Eu3+ Co-Doped Whitlockite Phosphates Ca8−xSrxZnEu(PO4)7: Bioactivity, Antibacterial Potential, and Luminescence Properties for Biomedical Applications" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121453

APA StyleDeyneko, D. V., Lebedev, V. N., Nikiforov, I. V., Titkov, V. V., Shendrik, R. Y., Barbaro, K., Caciolo, D., Aksenov, S. M., Fosca, M., Lazoryak, B. I., & Rau, J. V. (2025). Sr2+ and Eu3+ Co-Doped Whitlockite Phosphates Ca8−xSrxZnEu(PO4)7: Bioactivity, Antibacterial Potential, and Luminescence Properties for Biomedical Applications. Coatings, 15(12), 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121453