The Influence of Modifiers on the Performance of Recycled Asphalt Mixtures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Preparation of Asphalt Mixture

2.3. Measuring Process

2.3.1. The Measurement of Stability

2.3.2. The Measurement of Mechanical Strengths

2.3.3. The Measurement of Microscopic Properties

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Stability of Asphalt Mixtures

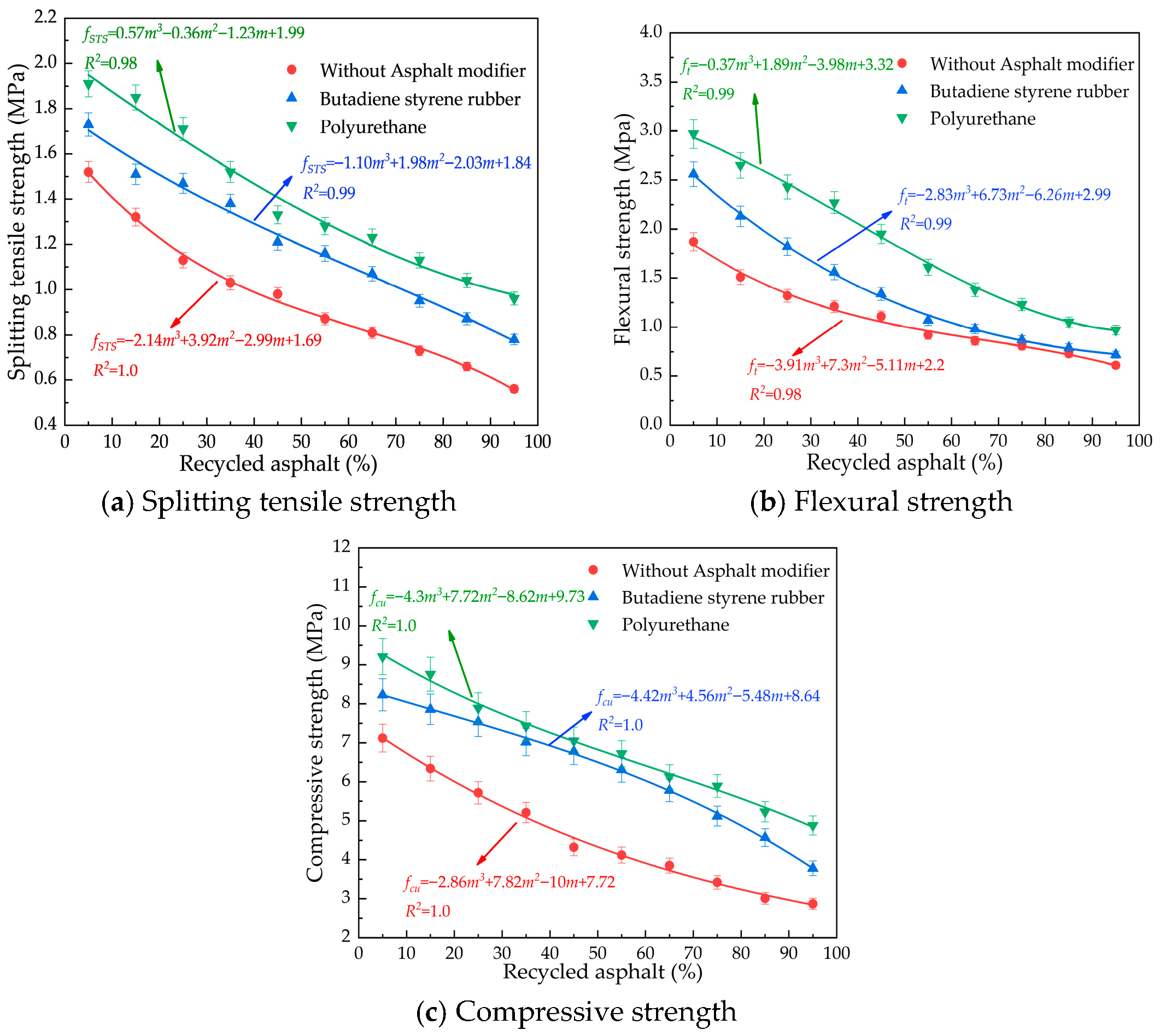

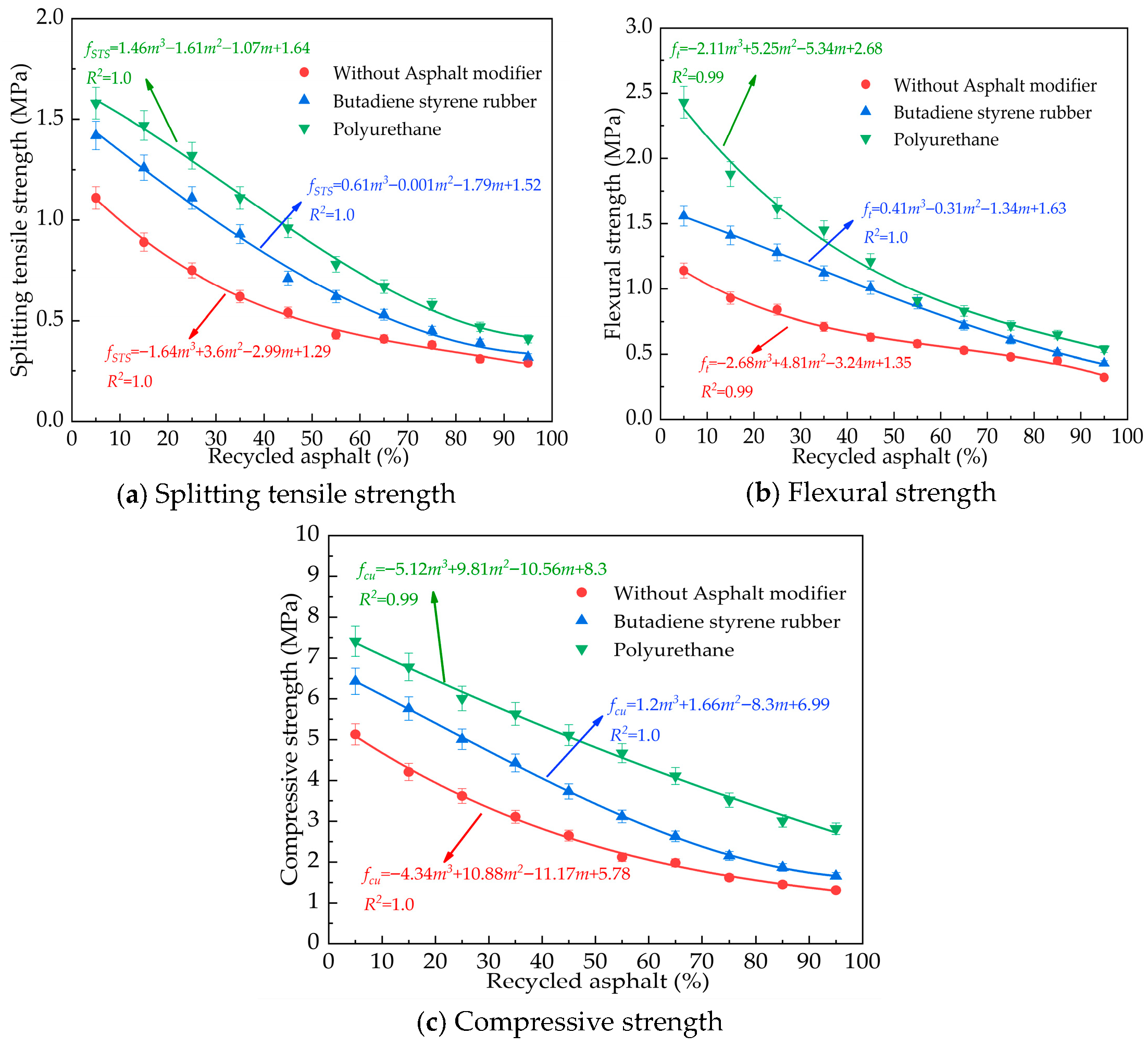

3.2. The Mechanical Strengths of Asphalt Mixtures

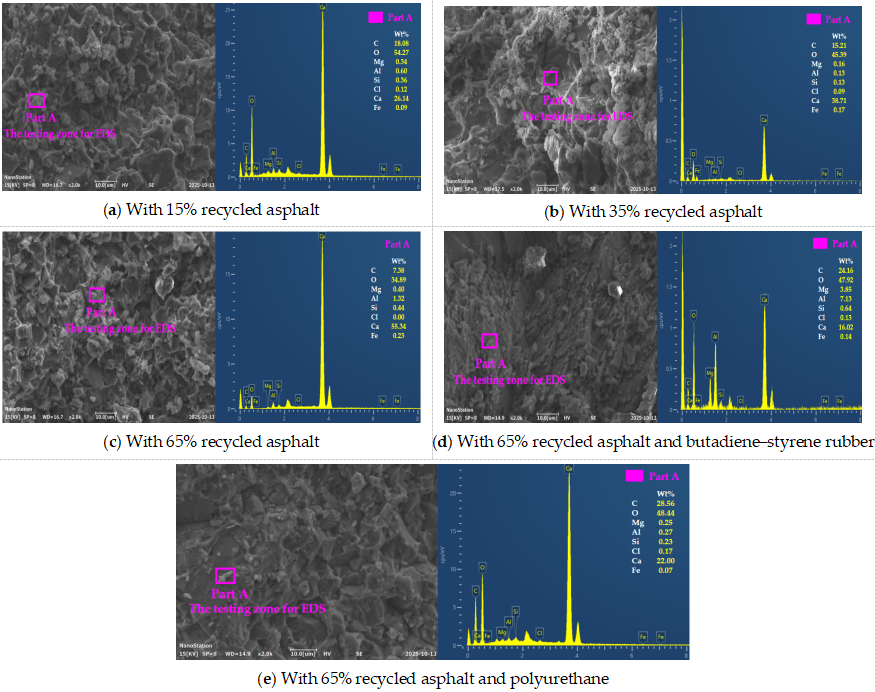

3.3. Microscopic Results

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The incorporation of recycled asphalt significantly impairs the stability and mechanical properties of asphalt mixtures, with the degree of deterioration increasing as a cubic function of the recycled asphalt content. Both water immersion and high-temperature (150 °C) aging substantially exacerbated this performance degradation, highlighting the poor moisture and thermal stability of unmodified recycled asphalt mixtures.

- (2)

- Modifiers effectively enhanced the overall performance of recycled asphalt mixtures. Both styrene–butadiene rubber and polyurethane significantly improved the stability and mechanical strengths. Polyurethane demonstrated superior performance in enhancing high-temperature stability and resistance to water damage, confirming its potential for application in demanding environments.

- (3)

- Microstructural analysis indicated that the addition of recycled asphalt reduced the contents of C and O, increased the relative concentrations of mineral elements such as Si and Fe, and led to a more porous structure, uncovering the intrinsic reason for the macroscopic performance decline. The introduction of modifiers effectively restored the continuity of the binder, strengthened the interfacial bonding, and improved the compactness and integrity of the material.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russo, N.; Filippi, A.; Carsana, M.; Lollini, F.; Redaelli, E. Recycling of RAP (Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement) as Aggregate for Structural Concrete: Experimental Study on Physical and Mechanical Properties. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2024, 1, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariyappan, R.; Palammal, J.; Balu, S. Sustainable use of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) in pavement applications—A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 45587–45606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Luo, B.; Luo, Z.; Xu, F.; Huang, H.; Long, Z.; Shen, C. Mechanical characteristics and solidification mechanism of slag/fly ash-based geopolymer and cement solidified organic clay: A comparative study. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 71, 106459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Leng, Z.; Lan, J.; Chen, R.; Jiang, J. Environmental and economic assessment of collective recycling waste plastic and reclaimed asphalt pavement into pavement construction: A case study in Hong Kong. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, L.F.; Mendes, L.P.T.; de Medeiros Melo Neto, O.; de Figueiredo Lopes Lucena, L.C.; de Figueiredo Lopes Lucena, L. Economic and environmental benefits of recycled asphalt mixtures: Impact of reclaimed asphalt pavement and additives throughout the life cycle. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 11269–11291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarsi, G.; Tataranni, P.; Sangiorgi, C. The challenges of using reclaimed asphalt pavement for new asphalt mixtures: A review. Materials 2020, 13, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azadgoleh, M.A.; Mohammadi, M.M.; Ghodrati, A.; Sharifi, S.S.; Palizban, S.M.M.; Ahmadi, A.; Vahidi, E.; Ayar, P. Characterization of contaminant leaching from asphalt pavements: A critical review of measurement methods, reclaimed asphalt pavement, porous asphalt, and waste-modified asphalt mixtures. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, B.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, X. Performance evaluation and feasibility study on reuse of reclaimed epoxy asphalt pavement (REAP). Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 450, 138653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, H.; Ullah, H.; Qiu, Y.; Abdrhman, H.; Fu, J.; Yang, E. Investigating the Performance of Asphalt Pavements Modified with Reclaimed Asphalt and Crumb Rubber. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Cao, L.; Guo, J.; Tan, Z. Restoring Road Performance of Recycled Asphalt Mastic through Filler Asphalt Ratio Adjustment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Khodaii, A.; Hajikarimi, P. A Multifaceted Purpose-Oriented Approach to Evaluate Material Circularity Index for Rejuvenated Recycled Asphalt Mixtures. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, F.A.C.; Guimarães, A.C.R.; Castro, C.D. Comparative study on permanent deformation in asphalt mixtures from indirect tensile strength testing and laboratory wheel tracking. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 305, 124736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Borges, P.; Santos, F.; Bezerra, A.; Van, W.; Blom, J. Cementitious binders and reclaimed asphalt aggregates for sustainable pavement base layers: Potential, challenges and research needs. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 265, 120325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Shi, C.; Yang, J. The feasibility of using epoxy asphalt to recycle a mixture containing 100% reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP). Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 319, 126122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasandín, A.R.; Pérez, I.; Gómez-Meijide, B. Performance of High RAP Half-Warm Mix Asphalt. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.K.; Das, U.; Patra, A.R. Utilization of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP) Materials in HMA Mixtures for Flexible Pavement Construction. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosperi, E.; Bocci, E.; Marchegiani, G. The Influence of Bitumen Nature and Production Conditions on the Mechanical and Chemical Properties of Asphalt Mixtures Containing Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement. Materials 2025, 18, 3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zou, G.; Wang, W. Study on the Water Stability and Safety Mechanism of Warm Mixed Recycled SBS Modified Asphalt Mixture. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Luo, J.; Lang, H.; Hua, F.; Yang, Y.; Xie, M. Study on the Micro-Surfacing Properties of SBR Modified Asphalt Emulsion with Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement. Mater 2025, 18, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z. Rheological property evaluation and microreaction mechanism of rubber asphalt, desulfurized rubber asphalt, and their composites. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, X.; Tian, P.; Yang, Y.; Xia, J. Experimental Studies and Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the Compatibility between Thermoplastic Polyurethane Elastomer (TPU) and Asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Jiao, B.Z. Thermodynamic properties analysis of warm-mix recycled a sphalt binders using molecular dynamics simulation. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2023, 25, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Jia, M.; Ban, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Huang, T.; Liu, H. Effects of Polyurethane Thermoplastic Elastomer on Properties of Asphalt Binder and Asphalt Mixture. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04020477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Sudarsanan, N.; Underwood, B.S.; Kim, Y.R.; Guddati, M. Reflective Cracking Performance Evaluations of Highly Polymer-Modified Asphalt Mixture. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2024, 150, 04024039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Sun, S.; Guo, N.; Huang, S.; You, Z.; Tan, Y. Influence on Polyurethane Synthesis Parameters Upon the Performance of Base Asphalt. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, J.; Yuan, S.; Yu, J.; Guan, Z.; Chai, H.K.; Wang, Q. Impact resistance and enhancing mechanism of a novel mortar integrated with shear thickening fluid. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 498, 144036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Li, M.; Qi, Z.; Yang, X.; Lin, Y.; Cao, S. A review on curve edge based architectures under lateral loads. Thin. Wall. Struct. 2025, 217, 113849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.S.; Liao, T.; Ji, Y.X.; Li, H.; Qu, Y.Z.; Huang, X.B.; Li, J. Biomimetic inspired superhydrophobic nanofluids: Enhancing wellbore stability and reservoir protection in shale drilling. Pet. Sci. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ji, Y.X.; Ni, X.X.; Lv, K.H.; Huang, X.B.; Sun, J.S. A micro-crosslinked amphoteric hydrophobic association copolymer as high temperature-and salt-resistance fluid loss reducer for water-based drilling fluids. Pet. Sci. 2024, 21, 1980–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Lv, K.; Qu, Y.; Ma, W. A Hyperbranched Copolymer as High-Temperature and Salt-Resistance Fluid Loss Reducer for Water-Based Drilling Fluids: Preparation, Evaluation, and Mechanism Study. SPE J. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Hao, J.; Wang, B.; Han, W. Comparative study on thermal and mechanical performances of liquid lead thermocline heat storage tank with different solid filling material layouts. Case. Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 73, 106754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Xiong, R.; Tian, Y.; Chang, M.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, B.; Wang, H.; Li, C. Preparation and Temperature Susceptibility Evaluation of Crumb Rubber Modified Asphalt Applied in Alpine Regions. Coatings 2022, 12, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG E20-2011; Standard Test Methods of Bitumen and Bituminous Mixtures for Highway Engineering. MOT: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Agarwal, B.; Behl, A.; Kumar, R.; Dhamaniva, A. Fatigue Failure Assessment of Asphalt Mixtures Containing 40% Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP) Under Short-Term Aging Conditions. J. Fail. Anal. Preven. 2025, 25, 1831–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Yan, K.; Wang, M.; Yuan, J.; Ge, D.; Liu, J. The Laboratory Performance of Asphalt Mixture with Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) and Amorphous Poly Alpha Olefin (APAO) Compound Modified Asphalt Binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 349, 128742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wei, J.; Xiong, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, X. Quantifying Moisture Susceptibility in Asphalt Mixtures Using Dynamic Mechanical Analysis. Coatings 2025, 15, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wang, J.; Jin, L. Study on the Performance and Mechanism of Graphene Oxide/Polyurethane Composite Modified Asphalt. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, H.; Zhang, W.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, C. Investigation of High Temperature Performance and Viscosity Characteristics of Modified and Unmodified Color Asphalt. Exp. Tech. 2022, 46, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, K.; Fan, X.; Tu, C. Performance Evaluation of Desulfurized Rubber Powder and Styrene-Butadiene-Styrene Composite-Modified Asphalt. Coatings 2025, 15, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, S.; Fried, A.; Preciado, J.; Castorena, C.; Underwood, S.; Habbouche, J.; Boz, I. Towards sustainable roads: A State-of-the-art review on the use of recycling agents in recycled asphalt mixtures. J. Cleaner. Prod. 2023, 406, 136994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Qian, Z.; Huang, Q.; Liu, P. Investigation on high-temperature stability of recycled aggregate asphalt mixture based on microstructural characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Cheng, X.; Sreeram, A.; Si, W.; Li, B.; Pipintakos, G.; Airey, D. Enhancing Fatigue Resistance and Low-Temperature Performance of Asphalt Pavements Using Antioxidant Additives. Mater. Struct. 2025, 58, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Fan, W. Evaluation and characterization of properties of crumb rubber/SBS modified asphalt. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 253, 123319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saffar, Z.H.; Yaacob, H.; Katman, H.Y.; Mohd Satar, M.K.I.; Bilema, M.; Putra Jaya, R.; Radeef, H. A review on the durability of recycled asphalt mixtures embraced with rejuvenators. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lin, Z.; Zou, G.; Yu, H.; Leng, Z.; Zhang, Y. Long-term performance of recycled asphalt mixtures containing high RAP and RAS. J. Road. Eng. 2024, 4, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Shi, C.; Ge, J. Research on Aging Characteristics and Interfacial Adhesion Performance of Polyurethane-Modified Asphalt. Coatings 2025, 15, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedi, G.H.; Dehnad, M.H. Effects of Dodecyl Amide, Nano Calcium Carbonate, and Dry Resin on Asphalt Concrete Cohesion and Adhesion Failures in Moisture Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; Ma, T.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Xu, G.; Wu, M. Investigating Mechanical Performance and Interface Characteristics of Cold Recycled Mixture: Promoting Sustainable Utilization of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 369, 133366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.M.; Elahi, A.; Waqas, R.M.; Kirgiz, M.S.; Nagaprasad, N.; Ramaswamy, K. Influence of Bentonite, Silica Fume, and Polypropylene Fibers on Green Concrete for Pavement and Structural Durability. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaleh, M.; Asadi, P.; Eftekhar, M.R. Life Cycle Assessment Based Method for the Environmental and Mechanical Evaluation of Waste Tire Rubber Concretes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, W. Performance of Asphalt Mixtures Modified with Desulfurized Rubber and Rock Asphalt Composites. Buildings 2024, 14, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chang, H.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Lin, J.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, W. High-Temperature Deformation and Skid Resistance of Steel Slag Asphalt Mixture Under Heavy Traffic Conditions. Buildings 2024, 14, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosa, P.; Pérez, I.; Pasandín, A.R. Evaluation of the shear and permanent deformation properties of cold in-place recycled mixtures with bitumen emulsion using triaxial tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 328, 127054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, C.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; He, Y.; Pei, J.; Lyu, L. Dry-Process Reusing the Waste Tire Rubber and Plastic in Asphalt: Modification Mechanism and Mechanical Properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 458, 139759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, D.; Liu, S.; Jiang, J.; Kan, J.; Tu, M. Analysis of asphalt microscopic and force curves under water-temperature coupling with AFM. Case. Stud. Constr. Mat. 2024, 20, e03071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Shan, L.; Tan, Y. Utilization of atomic force microscopy (AFM) in characterizing microscopic properties of asphalt binders: A review. J. Test. Eval. 2024, 52, 754–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, H.; Gao, M.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, Q.; Dong, Q. Nano-microscopic analysis on the interaction of new and old asphalt mortar in recycled asphalt mixture. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 825, 140593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Chemical Composition/% | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturates | Aromatics | Asphaltenes | Cycloalkyl Aromatics | |||||||

| CxH62 | C36H57N | C29H50O | C40H59N | C40H60S | C18H10S | C66H81N | C51H62S | C42H56O | C35Hy | |

| New asphalt | 11.13 | 5.63 | 7.03 | 5.62 | 5.65 | 21.1 | 4.48 | 2.98 | 4.48 | 31.90 |

| Type | Chemical Compositions/% | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | Na2O | K2O | |

| Coarse aggregate | 62 | 17 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Fine aggregate | 62.8 | 15.5 | 6.2 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 3.3 | 2.9 |

| Mineral Filler | 34 | 4 | 3 | 56 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Types | Particle Size/mm | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26.5 | 19.0 | 16.0 | 13.2 | 9.5 | 4.75 | 2.36 | 1.18 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0.075 | |

| Recycled asphalt | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.2 | 98.8 | 95.4 | 76.7 | 65.0 | 45.4 | 31.6 | 23.9 | 13.1 |

| Coarse aggregate | 100 | 100 | 100 | 94.0 | 19.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Fine aggregate | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.9 | 87.8 | 71.1 | 42.2 | 25.4 | 14.9 | 0.0 |

| Mineral Filler | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.8 | 84.5 |

| Recycled Asphalt | Coarse Aggregate | Fine Aggregate | New Asphalt | Butadiene–Styrene Rubber | Polyurethane | Mineral Filler | Recycled Asphalt Mass Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103.5 | 264.5 | 126.5 | 1564 | 120.06 | 120.06 | 69 | 5 |

| 308.2 | 236.9 | 112.7 | 1400.7 | 120.06 | 120.06 | 69 | 15 |

| 515.2 | 209.3 | 98.9 | 1235.1 | 120.06 | 120.06 | 69 | 25 |

| 719.9 | 181.7 | 85.1 | 1071.8 | 120.06 | 120.06 | 69 | 35 |

| 926.9 | 154.1 | 71.3 | 906.2 | 120.06 | 120.06 | 69 | 45 |

| 1131.6 | 126.5 | 59.8 | 740.6 | 120.06 | 120.06 | 69 | 55 |

| 1338.6 | 98.9 | 46 | 575 | 120.06 | 120.06 | 69 | 65 |

| 1543.3 | 71.3 | 32.2 | 411.7 | 120.06 | 120.06 | 69 | 75 |

| 1750.3 | 41.4 | 20.7 | 246.1 | 120.06 | 120.06 | 69 | 85 |

| 1955 | 13.8 | 6.9 | 82.8 | 120.06 | 120.06 | 69 | 95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Gao, C.; Xue, Q.; Yu, J.; Shi, F.; Lu, S.; Wang, H. The Influence of Modifiers on the Performance of Recycled Asphalt Mixtures. Coatings 2025, 15, 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121432

Wang X, Zhang H, Gao C, Xue Q, Yu J, Shi F, Lu S, Wang H. The Influence of Modifiers on the Performance of Recycled Asphalt Mixtures. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121432

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xuejie, Hui Zhang, Chenxi Gao, Qi Xue, Jia Yu, Feiting Shi, Shuang Lu, and Hui Wang. 2025. "The Influence of Modifiers on the Performance of Recycled Asphalt Mixtures" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121432

APA StyleWang, X., Zhang, H., Gao, C., Xue, Q., Yu, J., Shi, F., Lu, S., & Wang, H. (2025). The Influence of Modifiers on the Performance of Recycled Asphalt Mixtures. Coatings, 15(12), 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121432